5 Kandinsky Behr 3rd pass

5 Kandinsky Behr 3rd pass 5 Kandinsky Behr 3rd pass

- Page 2 and 3: Nonetheless, focusing attention exc

- Page 4 and 5: 9.Vasily Kandinsky, title page for

- Page 6 and 7: short plays (St. Petersburg, 1896)

- Page 8 and 9: 21.Thomas de Hartmann, musical scor

- Page 10 and 11: 25.Poster for Bilder einer Ausstell

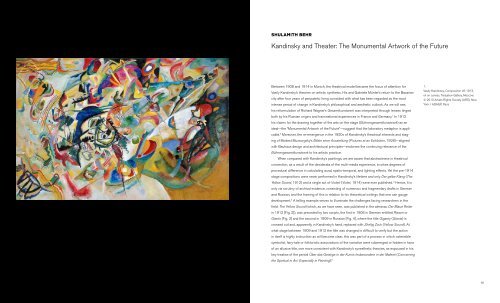

Nonetheless, focusing attention exclusively on the “veritable color-light spectacle” of TheYellow Sound limits the challenge to decipher the function of these performative elements inrelation to the apocalyptic, fable-linked themes and context of its publication in the almanac DerBlaue Reiter. Problematic, too, as the most well known of his stage compositions, its features aredeemed characteristic of all the plays; chronologically, semantically and formally, however, thereare vast differences between them. Just as the inconsistencies within <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s oeuvre resistan interpretation based on the evolution from figural representation to abstraction, so a developmentalanalysis of the stage-compositions, commencing in 1908–09 with the early scenariosDaphnis und Chloé, Grüner Klang (Green Sound), Schwarz und Weiss (Black and White), Riesen(Giants) and terminating with Violet in 1914, opposes such a conclusion. Contrary to expectation,the latter is the most accessible and least elusive of the stage works, signifying a contextsomewhat different from that which gave rise to the major Compositions V-VII (1911–13) [Fig.1]. 6 Hence, Violet, as well as the earlier stage-compositions, concedes to readings that appear totransgress the theoretical paradigms set up for them by <strong>Kandinsky</strong>.Before returning to these considerations, however, it is appropriate to pinpoint what triggered<strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s fascination with notions of artistic synthesis and his theatrical proclivitiesfor the disruption of narrative continuity, semantic dislocation between word and image, significanceattached to gesture, movement and lighting effects, and, above all, the lessons providedby Wagner’s music and theory. The isolation of such features requires firm anchorage in theimmense changes that overtook theatrical manifestations in the early twentieth century, aspectsof which are explored below.2.Vasily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, title page for Der gelbeKlang (The Yellow Sound), in Vasily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>and Franz Marc (eds.), Der Blaue Reiter, PiperVerlag, Munich, 1912. Neue Galerie NewYork. © 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS),New York / ADAGP, ParisArtistic Synthesis and Theatrical ReformThe phenomenon of the Doppelbegabung (double talent) in the early twentieth century is by nomeans restricted to <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, painting and literature being the most frequent combination ofthe arts since the Romantic period. Oskar Kokoschka and many others diverted their attention towriting, Arnold Schönberg representing a less common occurrence of composer turned painterand writer. 7 In many ways, the French Symbolists provided the momentum for artistic collaborationin the theater; Vuillard and Bonnard were closely associated with Paul Fort’s Théâtre d’Artand Lugné-Poë’s Théâtre de oeuvre during the early 1890s at the time of their greatest fascinationwith the plays of the Belgian poet and dramatist Maurice Maeterlinck. 8 The reasons artistswere attracted to the theater included the fact that it offered an entire art form in its own right, aswell as a medium for expanding the expressive potential of the other arts simultaneously.Indeed, it is not inconceivable that members of the avant-garde, remote from institutionaltraining and sponsorship, should seek to promote their image in more favorably heroic termsadopted from other disciplines. 9 There were notable historical precedents, moreover, where theresort to artistic interaction had led to cultural renewal; Richard Wagner, in his efforts to addressthe inadequacies of opera at the time, called upon the contribution of the poet towards achievingthe unity of drama and music that he so desired. 10 As laid out in his treatise Das Kunstwerk derZukunft (The Artwork of the Future, 1850), Wagner’s conception of the Gesamtkunstwerk, whilesuggesting the drawing together of the arts into an aesthetic totality, had its mystical and völkischcounterparts in envisioning a complex symbolic utopia. 113.Vasily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, first notes in Germantowards Riesen (Giants), 1908-09, pencil onpaper. Musée National d’Art Moderne, CentreGeorges Pompidou, <strong>Kandinsky</strong> Archive, Paris.© 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), NewYork / ADAGP, Paris4.Vasily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, corrections to Russian textGiganty (Giants), with title crossed out andreplaced with Zheltyj Zvuk (Yellow Sound),1909, ink on lined paper. Musée Nationald’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou,<strong>Kandinsky</strong> Archive, Paris. © 2013 ArtistsRights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP,Paris66 shulamith behr<strong>Kandinsky</strong> and Theater 67

Friedrich Nietzsche’s promotion of the Dionysian elements of Wagner’s music in Die Geburtder Tragödie aus dem Geiste der Musik (The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music, 1872) reinforcedthe values of instinctual expression, placing art at the center of his philosophy. 12 Evidently,the cultic reception of the ideas of both Wagner and Nietzsche in the fin de siècle was concomitantwith a profound change in beliefs. Artists, poets, and dramatists all stressed the importanceof the inner life in their subscription to a new geistige Kunst (spiritual art). In rejecting any principleof descriptive aesthetics, they turned to German idealist notions on the autonomous status ofthe work of art. As a consequence, the philosophical contentions of Arthur Schopenhauer’s treatiseDie Welt als Wille und Vorstellung (The World as Will and Idea, 1818) attracted many adherentsto the fundamental distinction that was drawn between our normal, everyday manner of6.Rolf Hoerschelmann, study for the posterfor Schwabinger Schattenspiele Theater(Schwaging Shadow-Play Theater), 1908,watercolor on paper. Staatliche GraphischeSammlung, Munich7.Robert Engels, poster for Max Reinhardt’sSeason at the Münchener Künstlertheater(Munich Artists’ Theater), 1909, coloredlithograph. Münchener Stadtmuseum5.Thomas Theodor Heine, Gastspiel: DieElfscharfrichter (Guest Performance:The Eleven Executioners), 1903,colored lithograph on paper. MünchenerStadtmuseum. © 2013 Artists RightsSociety (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonnlooking at the world and what he termed a state of “pure, objective, and will-less contemplation.” 13Just as significant for <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, among others, was Schopenhauer’s conviction that music wasthe most capable medium of all the arts in which metaphysical truth could be expressed. 14In varying degrees, the themes outlined above are revealed in numerous efforts tounleash an era of reform. In the first decade of the twentieth century, treatises continued to evokethe inspiration of Wagner’s The Artwork of the Future. Hence, the director Georg Fuchs’s DieSchaubühne der Zukunft (The Stage of the Future, 1905), Edward Gordon Craig’s The Art of theTheatre of Tomorrow (1905), and Isadora Duncan’s book Dance of the Future (1903) testify to thepossibilities made available to expand the range of theatrical expression. The fervor for progresswas international in character by virtue of the increased dissemination of ideas in journals devotedto cultural matters and the general mobility of many artists, directors, and writers.Nonetheless, it has been noted that each center of modern culture had a particular“confluence of political, socio-economic, and cultural characteristics that encouraged its localavant-garde movement to develop in a distinct manner.” 15 By 1900, developments in Munichcontrasted with those in Berlin, which was the undisputed center of naturalist drama. However,the Bavarian capital tended to promote less verbal and more gestural variants of modern theater,a not totally unexpected occurrence since Munich was pivotal to Jugendstil, the arts and craftsmovement as it was articulated in Germany. The cross-fructification of theater and the appliedarts was to be found in the most adventurous form of intimate theater—the notorious cabaretthe Elfscharfrichter (Eleven Executioners, Fig. 5) —, which appropriated the genres of populartheatrics (vaudeville and music halls) for entertainment. Indeed, as they stated in a circular,they paralleled their goals with the “arts and crafts movement, which has made the visual artssubservient to everyday life.” 16 Such was the commodification of popular theatrics that, by 1908,the Marionettentheater (Marionette Theater) and the Schwabinger Schattenspiele Theater(Schwabing Shadow-play Theater) [Fig. 6] were established as private ventures in Munich.Sponsored by the council in celebration of the 750 th anniversary of the city, the MünchenerKünstlertheater (Munich Artists’ Theatre) [Fig. 7], designed by Max Littman according to thespecifications of Georg Fuchs, equally aimed to eliminate the distinctions between high andlow culture by incorporating the inspiration of such genres within its productions. 17 An avidWagnerian, Fuchs aimed to reduce the illusory qualities of classical theater that held the spectatorat a distance. This was achieved by accentuating the shallow relief stage and by eliminatingthe proscenium arch [Fig. 8]. On the one hand, the reinstatement of cult, ritual, and rhythmicmovement as primary elements of theatrical renewal evoked Nietzsche’s Dionysian principles.On the other, the desire to infuse the audience with the fervor of völkisch communality stemmedfrom a cruder version of Wagner’s concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk.8.Max Littman, model for MünchenerKünstlertheater (Munich Artists’Theater), 1907–08, wood. DeutschesTheatermuseum68 shulamith behr<strong>Kandinsky</strong> and Theater 69

9.Vasily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, title page for Stichi bezslov (Poems without Words), 1903–04,wood cut on paper. The Museum of ModernArt, New York. © 2013 Artists RightsSociety (ARS), New York / ADAGP, ParisThe principle of employing artists as the designers of marionettes, shadow puppets, andstage-settings is one that would have been endorsed favorably by <strong>Kandinsky</strong>. Having arrived inMunich for training in 1896, he speedily developed a professional identity as an independentartist and pedagogue. By 1901, not only had he associated with members of the ElfscharfrichterKabarett (Eleven Executioners Cabaret), but he had also included original Scharfrichter masksby Wilhelm Hüsgen and marionettes designed by Waldemar Hecke for the sculptural sections ofexhibitions of the Phalanx group, a teaching and exhibiting association, based on Jugendstil principles,that <strong>Kandinsky</strong> had founded. 18 Contact with the ideas of Georg Fuchs and Peter <strong>Behr</strong>ensat the Darmstadt artists’ colony was secured by January 1902 and with the Symbolist poetics ofthe Stefan George/Karl Wolfskehl circle during 1903 and 1904.Apart from sharing enthusiasm for a spiritual art and a belief in the epochal renewal of lifethrough art, there were more specific thematic and stylistic links between <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s works andGeorge’s lyric poetry that allowed for cultural exchange: Jugendstil images of the garden or parkthat offer settings for meditation and nostalgia. 19 Such was the case in <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s evocation ofthe poetic muse in his portfolio of twelve woodcuts, Stichi bez slov (Poems without Words, 1903–04) [Fig. 9], containing scenes of Old Russia—peasants in costume, gallant mounted riders,elegant ladies, and onion-domed churches. 20 As is evident, although an expatriate, <strong>Kandinsky</strong>drew on his heritage and ethnographic training, remaining in contact with publishing circles inRussia and France; eight of the woodcuts that he created in Paris between 1906 and 1907 werereproduced as heliogravures in a portfolio Xylographies, which was issued by the symbolist periodicalTendances Nouvelles. 21 Tellingly, <strong>Kandinsky</strong> likened printmaking to music, placing two barsof an unconventional musical composition on the title page, above an enigmatic composition witha mounted rider (Flame, Fig. 11), a motif he repeatedly used to symbolize the battle for new art.<strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s easel painting similarly extended the boundaries of sensate experience; considerthe work Weisser Klang (White Sound) [Fig. 10], which was one of a group of eight worksconceived in Berlin in 1908, prior to <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s return to Munich in June of that year. Here wefind a reduction of allegorical content by means of a technically radical treatment of color, facture,and scale of both figure and ground.The evocative word Klang (sound) derives from the artist’s Goethean-based color theories,which expounded correspondences between color, sound, and psychological states of mind. 22According to <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, by means of finely tuned “vibrations,” the innerer Klang (inner sound) ofthe work of art would be communicated and resonate in the soul of the spectator. The adoptionof such terminology to connote metaphysical concepts of artistic expression and reception hasbeen attributed to his encounter with theosophy, since it was in Berlin, at the ArchitektenhausIn Munich, through 1909 and 1910, in addition to being conversant with a range of vanguardtheatrical reform, <strong>Kandinsky</strong> and Münter sustained these esoteric interests. Indeed, Steiner,having translated and directed performances of the French writer and theosophist enthusiastÉdouard Schuré’s Les Enfants de Lucifer (Children of Lucifer, 1900), initiated his own annualcycle of mystery dramas. 25 It was in this atmosphere and, moreover, in the large community ofRussian émigrés and subsequently in the Neue Künstlervereinigung München (NKVM: MunichNew Artists Association), that <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s theatrical activities took shape. Munich offered anideal gathering point for Russian expatriates and political dissidents, certainly as important acenter as Paris or Berlin. 26 The bohemian Schwabing, the university quarter of the city, wasa haven of cosmopolitanism and cultural exchange. Here the émigré composer Thomas deHartmann was a neighbor of <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s and the Russian artist and dancer Alexander Sacharoffa member of their circle. Framed by this collaboration, the following considers early stage scenariosbefore focusing on the impact of <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s trip to Russia in 1910 on The Yellow Sound andits theoretical implications in light of the essay preceding it (“Über Bühnenkomposition” or “OnStage Composition.”)on 26 March 1908, that <strong>Kandinsky</strong> and Münter attended Rudolf Steiner’s lecture “Sonne, Mondund Sterne” (Sun, Moon and Stars). 23 There Steiner proclaimed Goethe the pre-eminent naturalscientist who, in his Farbenlehre (Theory of Colors, 1812), intuited the spiritual beyond physicallight, which could be divined only via the “artistic imagination.” 2410.Vasily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, Weisser Klang (White Sound),1908, oil on board laid down on cradled panel.Private collection. © 2013 Artists Rights Society(ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris11.Vasily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, Index page for Xylographies(Xylographs), 1909, heliogravure after a woodcutfrom a portfolio of eight heliogravures. TheMuseum of Modern Art, New York. © 2013 ArtistsRights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris70 shulamith behr<strong>Kandinsky</strong> and Theater 71

Collaboration: Beyond the Symbolist Fusions des ArtsFounded in 1909, the NKVM, while providing an independent exhibiting outlet that accommodateda broad range of avant-garde practice, attracted support from the ranks of writers,composers, and performing artists. Attendance of the various salons that were held at the homeof the Russian artist Marianne Werefkin, a founding member of the group, generated much ofthis social and professional interaction. The Ukrainian-born Jewish artist and dancer AlexanderSacharoff [Fig. 12], who arrived in Munich via Paris in 1905, was well entrenched in this networkand served as the model for both Werefkin’s and Jawlensky’s portraits, which convey themystique of the unusual performer. 27Also Ukrainian by birth, the composer and conductor Foma Alexandrovich Gartman [Fig.14], known variously as Thomas von Hartmann and Thomas de Hartmann, studied harmony andcomposition under Anton Arensky and counterpoint with Serge Taneev, receiving his diplomafrom the St. Petersburg Conservatory at the age of eighteen. 28 Although twenty years youngerthan <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, De Hartmann had already achieved considerable success; in 1906 his fouractballet The Pink Flower was performed in the imperial opera houses of Moscow and St.Petersburg, with Vaslav Nijinsky, Anna Pavlova, and Michel Fokine dancing the principal roles. 29In 1908, De Hartmann was drawn to Munich to study with the famous Viennese-born conductorand former pupil of Wagner, Felix Mottl.Through the autumn of 1908 and, certainly, by February 1909, <strong>Kandinsky</strong> was collaboratingwith De Hartmann on the stage compositions. 30 In an undated typescript in English, the composerrecalled that they proceeded from scenes derived from Hans Christian Andersen and the Greeklegend of Daphnis and Chloé. Moreover, the enlisting of Sacharoff’s contribution was central tooffering an alternative to existing forms of ballet. 31 Their choice of Andersen’s fairy-tale ParadiseGarden and Daphnis and Chloé for theatrical composition was symptomatic of the symbolisttendency to seize on themes from pagan and folk culture, which served both as a refuge frommodern city life and as a departure for a new semi-religious mysticism. Indeed, Nietzsche’s glorificationof the sensuality of ancient Greek Dionysian cults inspired the Russian Symbolist poet andreligious anarchist Dmitri Merezhkovsky, in his own translation of Longus’s Daphnis and Chloé, toappend an introduction extolling the ideals of Eros. 32 The legendary protagonists were investedwith the significance of the new Adam and Eve appropriate to an eternally virginal paradise [Fig.13]. Fascinatingly, an edition of Merezhkovsky’s translation, with much underlining, can be foundin <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s personal library. 33From the fragmentary archival texts of Daphnis and Chloé, it is clear that the intentiondoesn’t stray far from the abovementioned source. Arranged in seven Bilder (Pictures), <strong>Kandinsky</strong>adopted the term from earlier Russian prototypes that wished to view each scene, akin tomedieval representations of the predetermined path of man through life, as a kind of animatedpicture. 34 The plot traces the vicissitudes of the goatherd and shepherdess on the island ofLesbos, from an initial Eden, through the Abduction of Chloé, Despair of Daphnis, Tempest,Reunion, Consent to Marriage, and Banquet. 35 There is no dialogue but, true to ancient Greektragedy, a chorus declaims the commentary in dactylic verse, a meter equally used in modernRussian elegiac poetry.<strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s directions and thumbnail sketches for the Prelude [Fig. 15] give some idea ofthe plans for movement and stage settings. Whereas the opening scene calls for the repetitionof slow figural movement, which implies the inspiration of Fuchs’s relief-stage, the other mise-enscènesrequire a more sophisticated stage technology to facilitate the growth and action of an“obscure black silhouette.” 36 Informatively, Hartmann noted at the time, “It is necessary to begintalks with Fortuny, for it seems that only with his machines is it possible to attain the desirable,i.e. noiseless, speedy change.” 37 Reference to the inventions of the Spanish-Italian designer andstage engineer Mariano Fortuny indicates the collaborators’ awareness of a broader spectrum oftheatrical reform. It was in Paris in 1902 that Fortuny first constructed a model of the sky-domewhich, in 1904, he described in Eclairage scénique système Fortuny. 38 Fundamentally a halfdomethat enclosed the stage, its use was of great relevance to <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s developing interestin creating dramatic lighting effects. Its surface was also receptive to the projection of mobilepictures of clouds or colors with greater effect than a flat backdrop.Verification that <strong>Kandinsky</strong> was informed, too, of the traditions associated with the plays ofMaeterlinck can be gauged from De Hartmann’s notes concerning the methods of interlinkingscenic change: “Scene changes should be carried out during the musically connected intermissions,like Pelléas, so that everything is like a dream—and so that nothing breaks the spirit.” 39Maeterlinck’s Pelléas and Mélisande (1892), a prose drama in five acts, was first produced byLugné-Poë in 1893 at the Théâtre Bouffes-Parisiens. 40 According to a critic, the stage waswrapped in a twilight gloom, the light filtering down over the figures and through a veil emphasizingthe poetic, dream-like atmosphere. 41 The first edition of the Russian translation of Maeterlinck’s12.Group photograph, from left to right:Alexander Sacharoff, MarianneWerefkin, Alexej Jawlensky, andHelena Nesnakomoff, ca. 1910. PSMPrivatstiftung Schlossmuseum13.Dmitri Sergeevich Merzhkovsky, Dafnis iKhloia: poviest’ Longusa, M.V. Pirozhkova,St. Petersburg, 1904. Musée nationald’art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou,<strong>Kandinsky</strong> Archive, Paris14.Photo of Blaue Reiter members taken byGabriele Münter on the balcony of<strong>Kandinsky</strong> and Münter’s apartment at no.36 Ainmillerstrasse, Munich 1911–12.From left to right: Maria and Franz Marc,Bernhard Koehler, Heinrich Campendonk,Thomas von Hartmann (in bowler hat),and Vasily <strong>Kandinsky</strong> (seated in front).Gabriele Münter- und Johannes Eichner-Stiftung, Munich72 shulamith behr<strong>Kandinsky</strong> and Theater 73

short plays (St. Petersburg, 1896) resides in <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s former library and it contains the earlycycle of dramas (The Intruder, The Blind Ones, Death of Tintagiles, 1890). 42 Originally designatedas “plays for marionettes,” they offered a more internalized idiom, which was achieved by extensiveuse of pauses, repetition of words and the carefully orchestrated use of sound.From the outset, it is evident that <strong>Kandinsky</strong> and De Hartmann wished to deploy the atmospheric—albeitprimarily static—fusions des arts of the Maeterlinck repertoire. However, wasthis at odds with the new synthesis of the arts heralded by Sacharoff’s experimental dance?<strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s directions for the third Picture, the “Despair of Daphnis,” signal that existing forms ofballet could not furnish what they sought:Onstage Daphnis is in despair. He seeks, runs, throws himself unexpectedly from side to side.Soon his hair flies apart and falls in his face, and he throws it back with his hands. Finally, hethrows himself in front of the statue of the nymph on his knees, praying, suddenly jumps up16.Veritas Studio, photograph of AlexanderSacharoff as Daphnis, ca. 1910-11. DeutschesTanzarchiv, Köln17.Program for Tanzabend Alexander Sacharoff,Weidenhof, Museum Folkwang Hagen, March24, 1911. Deutsches Tanzarchiv Köln18.Alexander Sacharoff, choreographic sketch fora performance, 1910, from Hans Brandenburg,Der moderne Tanz, Munich 1913, Plate IX.Deutsches Tanzarchiv Kölnand shakes his fists. 43Whereas <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s script conveys the protagonist’s im<strong>pass</strong>ioned response to the news of15.Vasily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, first page of the Russianmanuscript Daphnis und Chloé, 1908–09,Russian with a few sentences in German.Gabriele Münter- und Johannes Eichner-Stiftung, Munich © Artists Rights Society(ARS), New York / ADAGP, ParisChloe’s abduction, one can ascertain that this was distant from Sacharoff’s measured stylizations.Just as in the visual arts, Sacharoff imaginatively synthesized a range of traditions, from Egyptianthrough medieval, antithetical to the balletic canon [Fig. 16]. No doubt inspired by IsadoraDuncan’s questioning of the trappings and technical virtuosity of ballet, he entered a sphere ofperformance usually reserved for women—that of Der neue Tanz, or The New Dance. Criticalreviewers accordingly seized on the inability to identify a “character” as such; the meaning of theperformance defied morality by focusing attention on the instinctual eroticism of the hermaphroditefigure. Evidently, attributions of bisexuality drew on the discourses of anti-Semitism anddegeneracy and, in contravening the norm, Sacharoff was invested with the capacity to “open thesluice-gate of anarchy.” 44There is much to learn from the dancer’s choreography of solos (such as Daphnis orBacchantes), which were inspired by the poses of figures on ancient Greek vases. Accompaniedby De Hartmann’s musical compositions, this caused much controversy and discussion whenperformed in 1910 at the Tonhalle in Munich and, subsequently, at the Museum Folkwangin Hagen [Fig. 17]. 45 The reverse of the program included a commentary by Sacharoff,Bemerkungen über den Tanz (Remarks about Dance) that eulogized the role of male dancersin ancient Greek culture. He declared that the essentialism of the art of the new dance“stands between [the male and the female], yet at the same time unites the possibilities of bothgenders.” 46 Retaining merely an indexical relationship to Longus’s allegory of the legendary heroof bucolic poetry, Sacharoff’s diagram [Fig. 18] for one of the dance routines adopted numeralcodes that identified each graphic variation of pose and gesture, creating a relief-like, slow, rhythmicprogression independent of musical inspiration. Hence, while Sacharoff acknowledged theimpact of Duncan, he omitted her “bacchanalian leap” and, understandably, the abstraction inherentin his mannered movements offered a preview of “absolute” dance that was well suited to thecollaborative efforts of the threesome. 4774 shulamith behr<strong>Kandinsky</strong> and Theater 75

19 a–b.Thomas de Hartmann, diagram oforchestration for Riesen (Giants), 1908–09.Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, MunichWagner and Beyond: From Giants to The Yellow SoundIn the various drafts towards the stage composition Giants, the directions maintain elements ofsymbolist theatrics in calling for transparent curtains to fall in front of the giants and “projected”indistinct, small figures to slide over a hill. 48 However, De Hartmann’s musically based diagrams[Figs. 19a and b], differentiated into five scenes, indicate a more systematic attempt to interprettext and performance from the perspective of Wagnerian ideas on operatic reform. 49 Hence, theirjoint interest in Wagner was crucial to the method of underpinning, on a quasi-harmonic stave,the temporal progression of color, movement, and music on the stage.The Gesamtkunstwerk was seen by Wagner to be achieved by a unity of the melodic(language) conditioned by the harmonic (music), a notion that was invested with fecund andcosmological significance. 50 Notwithstanding the similar conceptions of harmonic arrangement,De Hartmann catered to <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s emphasis on the elements of Gegensatz (contrast) asopposed to the musical conditioning of the performance elements as propounded by Wagner.Closer examination of the musical stave towards the end of the first act [Fig. 19a] reveals that, asa “dark blue haze covers all,” movements of the figures slow down while the music (“wooden-like”choir and orchestra) battles forcefully. 51The giants, customarily associated with savageness and loss of intellectual ability in fairytales,the Homeric legend of Ulysses and Polyphemus, and the Nibelungen myth, first appearon the stage in a “crude green boat.” Just as Wagner cited the Hellenic prototype in his questto trace the simple mythos of the folk, so <strong>Kandinsky</strong> synthesized these sources with referencesto Russian folk culture. 52 Peasants, dressed in national costume (“Trachten”), carry flowers andrecite typically symbolist poetry (“The flowers of poetry are scattered all over the world. Gatherthem into an eternal wreath”). 53Subsequently, processions of people with colored banners and wreaths perform a dance.Inspiration for these themes can be traced to folk theater, which was closely related to seasonalagricultural rituals, in this instance to that of spring and summer. 54 In the second week afterEaster (Semik), processions of singing and dancing youths and maidens accompanied totemimages decked out in flowers.In <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s stage work, these festive events are accompanied by the large, yellow giants,who gesture aimlessly and are slow moving. Yet, these chthonic images are capable of spiritualimprovement, as demonstrated in the finale in which the central giant grows in height andapproximates the form of a cross by raising his arms upwards. The pencil drawing [Fig. 20] fromSketchbook 328 in the Gabriele Münter Foundation, presumed to be a study for this scene,acknowledges its origins in folk religious images of devotion. Interestingly, the combination ofthe folkloristic with lessons offered by Maeterlinck’s plays was not unprecedented in the Russiancontext. Particularly within the cabaret tradition, performances derived from such sources wereinterspersed with parodies of high culture; <strong>Kandinsky</strong> may have been aware of the Moscowcabaret Bat, which transformed Maeterlinck’s The Blue Bird into a puppet show shortly after itspremiere at the Moscow Arts Theater on September 30, 1908. 55 Indeed, during an extended visitto Russia between October and December 1910, <strong>Kandinsky</strong> wrote to Münter that he had seena production of this play but he complained that the performance was just right for the audiencefilled with children: “a fairy-tale with sprites … a philosophical-occult patchwork.” 56It is possible that Maeterlinck’s example no longer satisfied <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s theatrical aspirations.Certainly, the performance of symbolist plays quickly went out of fashion in Russia overthe next decade and <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s visit served to update his perspective on avant-garde developments.57 He made contact with the artist, theorist, and physician Nikolai Kulbin, who was basedin St. Petersburg. 58 The playwright Nikolai Evreinov’s drama Performance of Love was publishedby Kulbin in February 1910 in the deluxe anthology of essays on art, music, and theater, Studioimpressionistov, a copy of which was presented to <strong>Kandinsky</strong>. 59 The illustrations by Kulbin, amongothers, convey Evreinov’s notion of a constantly changing set; aimed to present the inner worldof the protagonist, this was achieved not only by color and intensity of light but also by variationsof scenery. 60 Acquaintance with these works may have served to assist <strong>Kandinsky</strong> out ofthe im<strong>pass</strong>e of symbolism since Evreinov’s Monodrama can be found in the provisional list ofcontents for the almanac Der Blaue Reiter. 61The Yellow Sound functions as the grand finale to this sequence of treatises on art, music,and theater and shares the characteristics of the almanac by the interspersal of its text withimages. 62 It is prefaced by an essay, “On Stage Composition,” which prompts the assumption thatthe theatrical work complies with the theoretical program. However, in that Giants anticipatedThe Yellow Sound, a longer more complicated gestation period belies the acuity of the introductorytext. In place of the undifferentiated five-scene arrangement of the former, The Yellow Soundis arranged in six Bilder (pictures) with a Prelude, which can only be described as “cosmic.” 63Thereafter, the five giants no longer arrive in a boat but “appear” on the stage. In Picture 2, thenational costumes, folkloristic processions bearing flowers, as detailed in Giants, are replacedby people in shapeless, differently colored garments. Their activities focus around the dramaticmovements of a single, large, and bent yellow flower with a prickly leaf. Instead of the poeticnostalgia for seasonal cycles and wreath-making celebrated in the chorus of Giants, The YellowSound cheerlessly leads the viewer via an awareness of self and inner perception through repetition(the figures carrying flowers chant “Close your eyes, close your eyes. Open your eyes, openyour eyes”). 64Such characteristics associate The Yellow Sound with salvation models and the eschatologicalthemes of his larger oeuvre. 65 The information that <strong>Kandinsky</strong> attended Steiner’s cycle of mysterydramas in Munich, the first of which, Die Pforte der Einweihung (The Portal of Initiation), was basedon Rosicrucian disclosure, provides a reading of the stage composition as a journey between thepoles of the material and the spiritual. 66 The possibility of salvation through art—the yellow giantsare earth bound, according to <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s color theories—is confirmed by the final sequence ofthe giant growing in height and assuming a cruciform shape against a blue background.It is feasible that the mystery drama facilitated <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s attempts to lift the theme ofGiants out of the fairy-tale element; thereby the tragic myth was invested with the potential20.Vasily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, sketchbook page withfigure approximating a cruciform, Picture 5,Riesen (Giants), 1908–09, pencil on graphpaper. Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus,Munich. © 2013 Artists Rights Society(ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris76 shulamith behr<strong>Kandinsky</strong> and Theater 77

21.Thomas de Hartmann, musical scorefor The Yellow Sound. The Thomas deHartmann Papers, Irving S. GilmoreMusic Library, Yale Universitymusic-strengthening dramatic action or the latter explaining the music, as in Wagner. It could bepursued by a series of combinations of music, movement, and color between the poles of oppositionand collaboration. 72 Intriguingly, notwithstanding their lack of performance, <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s stagecompositions did find a niche within debates on Expressionist and Bauhaus theatrical reform.to address the modern and urgent need for spiritual regeneration. Yet one has to distinguish<strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s approach from the narrower implications of the doctrinal and not preclude hisembrace of abstraction and the mystical “in the broadest sense.” 67 Indeed, from his treatiseOn the Spiritual in Art, we learn more about <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s vital interest in the Russian composerAlexander Scriabin’s experiments with music and the color keyboard, and there are valuable argumentsfor the programmatic impact of Scriabin’s Prometheus on The Yellow Sound. 68Of all the changes in The Yellow Sound, Picture 5 is the most inventive in inaugurating anexperimental dance and crowd routine only briefly inferred in Giants. Sacharoff was undoubtedlyimplicated as lead dancer in the choreographic antics of the people in tights, like Gliederpuppenor marionettes, as <strong>Kandinsky</strong> states in the directives. 69 In the meantime, he continued the collaborativeventure with De Hartmann on the score for the stage composition, the extant fragmentsfor Picture 5 [Fig. 21] revealing the radical, atonal <strong>pass</strong>ages of the composer’s manuscript, particularlywhen compared to the oriental, coloristic harmonies of the ballet suite The Pink Flower. 70While the inspiration of Wagner remained a potent undercurrent, <strong>Kandinsky</strong> challenged thislegacy in his essay “On Stage Composition.” Here he characterized drama, opera, and balletof the nineteenth century as retaining a description of material life. 71 Even the much admiredMaeterlinck and Wagner were tainted with the same brush as still being dominated by “externalaction.” The walls separating the three classes of stage works required annihilation in favorof a purer, internal unity. The monumental work of art need not follow a parallel course of theFrom Activist Expressionist to Gesamtkunstwerk BauhausThat <strong>Kandinsky</strong> soon became well known in Expressionist theatrical circles can be ascertainedfrom playwright and critic Hugo Ball’s fascination for the Russian’s genial personality, “most revolutionary”ideas, and “spiritual influence”. 73 In proposing a program for the summer season of theMünchener Künstlertheater, Ball included The Yellow Sound as one of the appropriate examplesof the “new theatrical expression.” 74 Such efforts to rejuvenate the Künstlertheater failed tomaterialize, as did Ball’s attempts to publish a book on Das neue Theater or ExpressionistischesTheater in collaboration with <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, Franz Marc, Thomas de Hartmann, Fokin, and others. 75Nonetheless, it is possible to reconstruct Ball’s conception of the “new theater,” which, interestingly,involved architectural plans aimed at creating a form of “Festpielhaus,” a theater of ritualperformance. 76 According to Ball, the aims of the Gesamtkunstwerk, in uniting the latest tendenciesin the arts (music, dance, word, and stage design), performed the function of “discharging”constrained psychic energies of the inner dramatic life. 77 As long as these aesthetic considerationswere radical, they satisfied the Expressionist ardor for revolutionary social reconstruction,such an interpretation revealing the fluidity of the Wagnerian legacy.In June 1914, the Neuer Verein, an established Munich literary club, permitted Ball to arrangesix matinées at the Kammerspiele. One of these sessions was to be devoted to an exhibition of<strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s works accompanied by an act of his new stage composition Der violette Vorhang (TheViolet Curtain), a copy of which had been placed “at Ball’s disposal.” 78 Ultimately, the outbreak ofWorld War I prevented fulfillment of these schemes. The significance of the initial title, thereafterreduced to Violet, can be gauged from the fact that the drapes framing the stage often becomepart of the props and hinder the actors. Together with <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s codification of violet as a colorthat has morbid, funerary associations, one can gather that the function of the curtains as destinyis greater than that of the characters. Humanity, at one with nature and the universe, a neo-romanticstrain not uncommon to Expressionism, is threatened by unknown forces.Arranged in seven pictures with two interludes of abstract, kaleidoscopic lighting events, thetext of Violet avoids visionary, temporal abstractions, such as “later” or “after some time,” as reliedupon in The Yellow Sound. Instead, pauses, indicated by calculated seconds in brackets, are usedfor emphasis between different staging directives. 79 In Violet, we are given an accelerated paceof the dramatic effects, signifying a considerable change of style. This observation is particularlyapplicable to sound effects, which include the use of musical instruments and bruitist noises(urban, military, and domestic). These alternate with speech or correlate with movement and lightingeffects. The musical score, therefore, is not an orchestrated development of theme and variation,as initiated by De Hartmann for The Yellow Sound, but corresponds to the alliteration of the22.Vasily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, Eventuelle Melodien fürBild I und II, musical manuscript for Violet,1914. Musée national d’art moderne, CentreGeorges Pompidou, <strong>Kandinsky</strong> Archive,Paris. © 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS),New York / ADAGP, Paris78 shulamith behr<strong>Kandinsky</strong> and Theater 79

23.Vasily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, Violet III, mise-en-scènefor Picture III, 1914, pencil, watercolor andink on paper. Musée national d’art moderne,Centre Georges Pompidou, <strong>Kandinsky</strong>Archive, Paris. © 2013 Artists RightsSociety (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Parisand spit. Apocalyptic hope and cultural pessimism exist alongside each other, as palm trees fall,and refrains, vocalizing the collapse of the ramparts, consistently threaten the absurdities of thehuman condition. 82But the urgent imperatives of pre-war Munich were distant from 1920s Bauhaus and, inreworking the final picture of Violet for publication—Aus “Violett,” Romantisches Bühnenstück—<strong>Kandinsky</strong> diluted its meanings. 83 He retained the outward details of the servants repeating ameaningless set of actions, carrying a luxuriously set table from one part of the stage to another,in response to the orders of a chimney sweep. However, he omitted critical sequences wherethey alternate carrying the table with a stretcher bearing a body, which is covered by violet draping.84 No doubt the interdisciplinary principles of the Bauhaus in general and Oskar Schlemmer’slaboratory approach towards space and the human body in his Triadic Ballet (1922) in particularrekindled <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s theatrical experimentation. 85 Just as important was the return, after yearsof legal wrangle, of a portion of his oeuvre and writings that were left in Münter’s possession atthe outbreak of World War I. 86In 1928, <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s staging of Modest Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition [Fig. 24], forwhich he designed the sets and costumes, represented a climax of his theoretical aims for themonumental drawing together of the arts. The premiere took place at the Friedrich-Theater inDessau [Fig. 25], conducted under the baton of Artur Rother. <strong>Kandinsky</strong> transformed the ten24.Vasily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, Bild III, Gnomus (SceneIII, Gnome), ca. 1928, ink, tempera, andwatercolor on paper, stage set design forModest Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition,for performance at the Friedrichtheater,Dessau, April 1928. TheaterwissenschaftlicheSammlung der Universität zu Köln. © 2013Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York /ADAGP, Parisindividual instrument’s timbre (“Boum” of drum or “Trou-ou” of trumpet). Significantly, <strong>Kandinsky</strong>had all intentions of satisfying Edward Gordon Craig’s ideas regarding the crucial nature of thestage director for restoring the art of the theater to “its own creative genius.” 80 A single sheet ofmusic, Eventuelle Melodien für Bild I und II [Fig. 22], in <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s hand reveals his arrangementof radical sound effects (bruitist, vocal, and instrumental), comparable to the techniques of Italianand Russian Futurism.While <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s influence on Ball has been the exclusive focus in the secondary literature,it is apparent that the latter may have been instrumental in redirecting <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s notionof the Bühnengesamtkunstwerk towards breaking through the “sterile crust of society.” 81 Eventhe nature idyll of the third picture [Fig. 23], with figures dressed colorfully in Russian costume,caricatures the primordial referents, as a bloated, deliberately awkward red cow dominates thesetting. The fine balancing act that <strong>Kandinsky</strong> strove to preserve in The Yellow Sound betweenthe principles of construction and chaos, the Apollonian and the Dionysian, was dispensed within Violet, as motifs of the modern world invade the stage composition. The parodying of socialclasses constitutes a new departure for <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s theatrical material, as three out of the sevenpictures focus on an elegantly dressed bourgeoisie, whose verbal exchange is frustrated. Thefluctuations between curtailed speech and contrived self-consciousness point to a scenario offarce and cabaret. Other levels of society are similarly unflattering; in the sixth act, the workers,who wheel in a cart surmounted by a green parrot in a golden cage, stop, blow their noses,80 shulamith behr<strong>Kandinsky</strong> and Theater 81

25.Poster for Bilder einer Ausstellung(Pictures at an Exhibition), April 11, 1928,Friedrich-Theater Dessau“pictures” into sixteen scenes and was assisted by the artist Paul Klee’s son Felix, who latermade a short score of the choreography. 87 Unlike the gestation of The Yellow Sound, theorypreceded performance. In his essay “Über die abstrakte Bühnensynthese” (“On Abstract StageSynthesis”), which was published in the first Bauhaus publication in 1923, <strong>Kandinsky</strong> integratedhis experiences as a member of the People’s Commissariat for Education in the VisualArts (Izo-Narkompros) in post-revolutionary Soviet Russia. In arguing for theatrical renewal, hedismissed drama, opera, and ballet as stultifying museum forms and directed his attention toencom<strong>pass</strong>ing architecture and the stage within the abstract laws of theater (color, sound, movement).88 In so doing, <strong>Kandinsky</strong> disclosed the continuing importance and embodiment of modernspectatorship (stripped of the mystical terminology). As he stated, architecture coordinated “alleyes in one direction, all ears to a source.” 89 Hence, innovation, as a by-product of intensiveresearch and not as an end in itself, meant that the theatrical medium was central both to hispedagogy and to a science of the arts.Walter Benjamin’s contention that “technology has subjected the human sensorium to acomplex kind of training” is confirmed by this desiderata of the multi-media experience. 90 Theseparate but equal treatment of color, movement, sound, and stage results in the calculationof a complex structure of consonances and dissonances contrived to make the observer theactive producer of his or her own content. This gives rise to two seemingly irreconcilable modelsof subjective vision—the physiological subject and the autonomous viewer—and it is debatablewhether the spectator is capable of synthesizing the elements of <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s “harmony ofcontrasts” in line with his intentions. As we are aware, Theodor Adorno’s Marxist critique of theWagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk argued that it was no more than a cover for the underlying fragmentationof society and culture. 91 Yet the stage compositions were distant from the commoditizedexperiences of Bayreuth and, as a whole, lay little claim to imaging the world. This givescredence to the argument that “modernism itself must be understood in reference to the theoreticalelaboration and historical development of the Gesamtkunstwerk.” 921 This essay is based on material in Shulamith<strong>Behr</strong>, “<strong>Kandinsky</strong> as Playwright: the Stage-Compositions 1908–1914,” PhD Thesis,University of Essex, 1991.2 Wassily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, “ÜberBühnenkomposition,” in Der Blaue Reiter,Wassily <strong>Kandinsky</strong> and Franz Marc (eds.), R.Piper, Munich, 1912, pp. 101–113.3 Wassily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, Der gelbe Klang, in DerBlaue Reiter, Wassily <strong>Kandinsky</strong> and FranzMarc (eds.), R. Piper, Munich, 1912, pp.115–131; “aus violett, romantisches bühnenstückvon <strong>Kandinsky</strong>,” bauhaus , no. 3, 1927,p. 6.4 Archival sources, drawn from the GabrieleMünter- und Johannes Eichner-Stiftung,Munich, Städtische Galerie im LenbachhausMünchen, the Archives <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, CentreGeorges Pompidou, Musée national d’artmodern, Paris, are published in a tri-lingualedition (French, German, Russian) <strong>Kandinsky</strong>:Du théâtre, Über das Theater, O Teatre,Jessica Boissel (ed.) with the collaborationof Jean-Claude Marcadé, Société <strong>Kandinsky</strong>,Paris, 1998.5 Wassily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, Über das Geistige in derKunst: Insbesondere in der Malerei, R. Piper,Munich, 1912.6 These paintings were subtitled: CompositionV: Resurrection (1911), Composition VI:Deluge (1913); Composition VII: LastJudgement (1913). Illustrations are availablein Hans K. Roethel and Jean K. Benjamin,<strong>Kandinsky</strong>: Catalogue Raisonné of the OilPaintings, vol. I (1900–1916), London, 1982,cat. nos. 400, 464 and 476, respectively.7 For a discussion of the artist/playwrightphenomenon consult Peter Vergo andYvonne Modlin, “Murderer Hope of Woman:Expressionist Drama and Myth,” in exh. cat.Oskar Kokoschka 1886–1980, Tate Gallery,London, 1986, pp. 20–31.8 French Symbolist theatrical manifestationsare dealt with in Gösta Bergman’s, Denmoderna teaterns genombrott, Stockholm,1966, pp. 67–95.9 Paul Levesque, “Jahrhundertwende, Finde Siècle Wilhelminian Era: Re-examiningGerman Literary Culture 1871–1918,”German Studies Review, vol. 13, no 1,February 1990, pp. 16, 20. In literary spheres,it is significant that the self-valorizationattached to the terms Genie and Dichtertumestablished themselves as component partsof the Wilhelmine literary vocabulary right upto and including the Expressionist period.10 Richard Wagner, “Opera and Drama II”(1850–51), in Wagner on Music and Drama,A Goldman and E. Sprinchorn (eds.), London,1970, p. 188: “But it can succeed in thehands of none but that Poet who is fullyalive to music’s tendence and faculty ofexpression.”11 Richard Wagner, Das Kunstwerk der Zukunft,Otto Wigand, Leipzig, 1850; The Art-Work ofthe Future, in Richard Wagner’s Prose Works,William Ashton Ellis (trans.), Kegan Paul,London, 1892, pp. 69–215.12 Friedrich Nietzsche, Die Geburt der Tragödieaus dem Geiste der Musik, E. W. Fritzsch,Leipzig, 1872.13 Arthur Schopenhauer, The World as Will andIdea, (1818), Routledge, London, 1964, pp.271–272.14 Ibid. p. 336: “The composer reveals the innernature of the world, and expresses the deepestwisdom in a language his reason does notunderstand, as a person under the influenceof mesmerism tells things of which he has noconception when he awakes.”15 Peter Jelavich, Munich and TheatricalModernism. Politics, Playwriting andPerformance 1890–1914, Harvard UniversityPress, Cambridge (Mass.) and London, 1985,pp. 5–6.16 See Peter Jelavich, “Die Elfscharfrichter:the Political and Socio-Cultural Dimensionsof Cabaret in Wilhelmine Germany,” in Turnof the Century: German Literature and Art1890–1914, Gerald Chapple and Hans H.Schulte (eds.), Bonn, 1981, p. 512, quotingfrom the supplement to the Scharfrichters’,“Zeichnungserklärungen bei Gründung desKabaretts” (1901).17 For a survey of theatrical reform in Munichsee Peter Jelavich, Munich and TheatricalModernism. Politics, Playwriting andPerformance 1890–1914, Harvard UniversityPress, Cambridge (Mass.) and London, 1985;for the impact of the Gesamtkunstwerkon theatrical architecture see Juliet Koss,Modernism after Wagner, University ofMinnesota Press, Minneapolis, 2010.18 Peg Weiss, <strong>Kandinsky</strong> in Munich: the FormativeJugendstil Years, Princeton University Press,New Jersey, 1979, p. 58.19 Peg Weiss, <strong>Kandinsky</strong> in Munich: the FormativeJugendstil Years, 1979, pp. 86–91.20 Wassily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, Stichi bez slov (Poemswithout Words, 1903–04), portfolio of twelvewoodcuts, mount 32.9 x 24.9 cm, StroganovAcademy, Moscow.21 Les Tendances Nouvelles, which had previouslypublished thirty-three woodcuts by<strong>Kandinsky</strong>, issued this portfolio comprisingreproductions of woodcuts from 1907.<strong>Kandinsky</strong> had befriended the publication’seditor, Alexis Mérodack-Jeaneau, while livingin Paris from 1906 to 1907. Xylographies(Xylographs) 1909, (prints executed 1907).Portfolio of eight heliogravures after woodcuts(including front cover, back cover andtitle page); sheet: 32 x 32 cm, TendancesNouvelles, Paris.22 For a nuanced interpretation of the impactof Goethe’s Farbenlehre (Theory of Colors,1810) see Christopher Short, The Art Theoryof Wassily <strong>Kandinsky</strong> 1909–1928: The Questfor Synthesis, Peter Lang, Bern et al, 2010,pp. 29–40.23 Sixten Ringbom, The Sounding Cosmos: AStudy in the Spiritualism of <strong>Kandinsky</strong> and theGenesis of Abstract Art, Åbo Akademi, Åbo,1970, pp. 37–39.24 Rudolf Steiner, “Sonne Mond und Sterne,”Berlin, 26 March 1908, Rudolf Steiner OnlineArchive, http://anthroposophie.byu.edu, 4.Auflage 2010, p. 8: “Solange man nur dasphysische Licht sieht, wird man dies nichtverstehen können, denn Geistiges kann nurmit künstlerischer Phantasie erahnt, im sinnlich-übersinnlichenSchauen als Bild erlebt,durch Geistesforschung erfahren werden.”25 See Helmut Zander, Anthroposophie inDeutschland: Theosophische Weltanschauungund gesellschaftliche Praxis 1884–1945, vol.2, Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, Göttingen,2007, pp. 1026–1029.26 Adrienne Kochman, “Russian émigré artistsand political opposition in fin-de-siècleMunich,” Emporia State Research Studies, vol.45, no. 1, 2009, pp. 6–26.27 For the impact of Sacharoff’s Neue Tanzon Werefkin’s oeuvre, see Shulamith<strong>Behr</strong>, “Veiling Venus Gender and Painterly82 shulamith behr<strong>Kandinsky</strong> and Theater 83

Abstraction in Early German Modernism,” inManifestations of Venus: Essays on Genderand Sexuality, Caroline Arscott and KatieScott (eds.), Manchester University Press,2000, pp. 126–141.28 Charlotte Douglas, Swans of Other Worlds:Kazimir Malevich and the Origins ofAbstraction in Russia, Ardis, Ann Arbor, 1980,p. 89, note 9, identifies De Hartmann’s originalname.29 The New Grove Dictionary of Music andMusicians, Macmillan, London, 1980, pp.268–269.30 Wassily <strong>Kandinsky</strong> and Gabriele Münter,Letters and Reminiscences, Annegret Hoberg(ed.), Prestel, Munich, 1994, p. 47.31 Thomas de Hartmann, “About <strong>Kandinsky</strong>”(n.d.), Unpublished typescript in English, MSS46. The Thomas de Hartmann Papers, IrvingS. Gilmore Music Library, Yale University, Box24, Folder 215.32 Bernice G. Rosenthal, Dmitri SergeevichMerezhkovsky and the Silver Age: TheDevelopment of a Revolutionary Mentality,Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague, 1975, pp. 63–4.33 Dmitri Sergeevich Merezhkovsky, Dafnis iKhlo· iǎ: poviesta Longusa, M.V. Pirozhkova, StPetersburg, 1904. <strong>Kandinsky</strong> Archive, CentreGeorges Pompidou, Musée national d’artmodern, Paris.34 Wassily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, “On Stage-Composition,”1912, in Complete Writings, eds. KennethLindsay and Peter Vergo, Da Capo, Boston(Mass.), 1994, p. 260. Here <strong>Kandinsky</strong>mentions Leonid Andreev’s play Life of Man(1906). Inspired by the viewing of Dürer’swoodcuts in Germany, Andreev replaced theterm “act” by “picture”. See J. M. Newcombe,Leonid Andreyev, Bradda, Letchworth, 1972,p. 97.35 Wassily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, Daphnis und Chloé,1908–1909, Russian with a few sentencesin German, Gabriele Münter- und JohannesEichner-Stiftung, in <strong>Kandinsky</strong>: Du théâtre,Über das Theater, O Teatre, Document Nr. 4R,pp. 38–45.36 Ibid. p. 38: “Vorspiel: Bild, langsam nacheinandergehende Figuren, Chorus mit gleichenBewegungen. Bild: schwarzes Schiff Bild:rotes Meer, aus den Wogen rechts, plötzlichbis zur Decke wachsend, ruckt hervor eineunklare schwarze Silhouette und greift nachdem Schiff. Sofort dunkel./ Prelude: Picture,slowly one after another continuous figures,chorus with the same movements. Picture:black ship. Picture: red sea, from the waveson the right, suddenly growing towards theceiling, an obscure black silhouette lurchesout and grabs the ship. Immediately dark.”37 Thomas de Hartmann, Unpublished notes inRussian towards, Daphnis und Chloé, blackschool book, 20.8 x 17 cm, Städtische Galerieim Lenbachhaus, München, GMS 415, p. 1.38 Gösta M. Bergmann, Lighting in the Theatre,Almqvist, Stockholm, 1977, p. 340.39 Thomas de Hartmann, Unpublished notes inRussian towards, Daphnis und Chloé, blackschool book, 20.8 x 17 cm, Städtische Galerieim Lenbachhaus, München, GMS 415, p. 1.40 Gösta M. Bergmann, Den moderna teaternsgenombrott, pp. 85–86.41 Ibid. and note 17, pp. 550–1, quoting Échodes Paris, 17 May 1893.42 Gabriele Münter- und Johannes Eichner-Stiftung, Munich, Städtische Galerie imLenbachhaus München.43 Wassily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, Daphnis und Chloé ,1908–09, Russian with a few sentences inGerman, Gabriele Münter- und JohannesEichner-Stiftung, in <strong>Kandinsky</strong>: Du théâtre,Über das Theater, O Teatre, Document Nr.4R, p. 44: “Auf der Bühne ist Daphnis inVerzweiflung. Er sucht, läuft, wirft sich unerwartetvon einer Seite zur anderen. Bald fliegenseine Haare auseinander, bald fallen sieins Gesicht, und er wirft sie mit den Händenzurück. Schließlich wirft er sich vor der Statueder Nymphe auf die Knie, betet, springt plötzlichauf und rüttelt die Fäuste . . .”44 Friedrich Markus Huebner, “AlexanderSacharoff,” Phöbus, vol. 1, no. 3, 1914,pp. 103–104: “Sacharoff lockert dieseNorm. Er öffnet die Schleusentore desAnarchischen. Er stellt dar und glorifiziertdas ‘Charakterlose’.” For a comprehensiveaccount of the stereotypes of Jewish identityand difference see Sander L. Gilman, TheJew’s Body, New York and London, 1991.Consult also Patrizia Veroli, “The Mirror andthe Hieroglyph: Alexander Sacharoff andDance Modernism” in Die Sacharoffs. ZweiTänzer aus dem Umkreis des Blaue Reiters,Frans-Manuel Peter and Rainer Stamm (eds.),Wienand, Cologne, 2002, pp. 178–9.45 Rainer Stamm, “Alexander Sacharoff —Bildende Kunst und Tanz,” in Die Sacharoffs.Zwei Tänzer aus dem Umkreis des BlaueReiters, 2002, pp. 11–4546 Alexander Sacharoff, “Bemerkungen über denTanz,” reproduced from the program circularfor the Tanz-Abend (June 21, 1910) at theTonhalle, Munich, in Die Sacharoffs. ZweiTänzer aus dem Umkreis des Blaue Reiters, p.46: “das noch zwischen den beiden steht undnoch gleichsam die Möglichkeiten der beidenGeschlechter in sich vereinigt.”47 Hans Brandenburg, Der Moderne Tanz, GeorgMüller, Munich, 1913, pp. 121–122.48 <strong>Kandinsky</strong>: Du théâtre, Über das Theater, OTeatre, Document Nr. 6, pp. 54–67.49 Thomas de Hartmann, diagrams in Russianand German towards Riesen, black schoolbook, 20.8 x 17 cm, Städtische Galerie imLenbachhaus, München, GMS 415, pp. 5(verso) – 6 (verso).50 Richard Wagner, “Opera and Drama II”(1850–1), Wagner on Music and Drama, p.235.51 Susan Stein, “<strong>Kandinsky</strong> and Abstract StageComposition: Practice and Theory, 1909–1912,” Art Journal, vol. 43, Spring 1983, pp.61–66.52 Richard Wagner, “A Communication to myFriends” (1851), Wagner on Music and Drama,pp. 261–262. The main mythos of the FlyingDutchman is traced to the Hellenic Odyssey,the outlines of the myth of Lohengrin to thestory of Zeus and Semele.53 Wassily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, unpublished notes inGerman towards Riesen, 1908–09, blackschool book, 20.8 x 17 cm, StädtischeGalerie im Lenbachhaus, München, GMS415, pp. 7–8: “Szene öffnet sich und eswird sichtbar grellgrünen Hügel auf violettenHintergrund mit einfachen bunten Blumen.Von links erschienen Menschen in hellenTrachten mit vielen Blumen—Sie sprechenmusikalisch: ‘Die Blumen der Dichtung sindüber die Weltgesträut [sic.]. Sammle sie zueinem ewigen Kranz. In der Wüste wirst dunicht einsam sein, im Gefängnis frei’ [….]Musik die immer greller wird, Grelle bunteMenschenprozession mit Fahnen, Kränzen,Tanz.”54 Elizabeth A. Warner, The Russian Folk Theatre,Mouton de Gruyter, Hague and Paris, 1977, p.23.55 Segel, Turn of the Century Cabaret, p. 262.56 Wassily <strong>Kandinsky</strong> letter to Gabriele Münter,26 October/ 8 November 1910, cited inGisela Kleine, Gabriele Münter und Wassily<strong>Kandinsky</strong>, Insel, Frankfurt/Main, 1990, p.355.57 Konstantin Rudnitsky, Russian and SovietTheatre: Tradition and the Avant-Garde,Thames and Hudson, London, 1988, p. 10.58 <strong>Kandinsky</strong> was in Moscow from October 14to November 29, St. Petersburg October 30to 31, Odessa 1 to 20 December 1910.59 Jelena Hahl-Koch, “<strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s Role inthe Russian Avant-Garde,” in exh. cat. TheAvant-Garde in Russia 1910–1930: NewPerspectives, Los Angeles County Museumof Art, 1980, pp. 85, elucidates on Kulbin’srole in founding the Society of IntegratedArt (ARS), in spring 1911, in which painters,musicians, dramatists and performers wereto work together. <strong>Kandinsky</strong> and Schoenbergwere invited to become members. Amongthe notables mentioned for collaborationwas Alexander Blok for the literary section,Evreinov in charge of theater and Fokine forchoreography.60 Chistopher Collins, Life as Theatre: FiveModern Plays by Nikolai Evreinov, Ardis, AnnArbor, 1973, pp. xiii–xiv.61 Franz Marc, Letter to Reinhard Piper,September 10, 1911, in Andreas Hüneke(ed.), Der Blaue Reiter: Dokumente einer geistigenBewegung, Reclam, Leipzig, 1991, p. 80.62 Susan A. Stein, “Ultimate Synthesis:An Interpretation of the Meaning andSignificance of Wassily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s TheYellow Sound,” M.A. Diss., State Universityof New York at Binghampton, 1980,pp.119–126, considers the discourses of thepublication of The Yellow Sound as imageand text. See also Felix Thürlemann, “FamoseGegenklange: Der Diskurs der Abbildungenin Almanach ‘Der Blaue Reiter,’” exh. cat. DerBlaue Reiter, Kunstmuseum Bern, 1986, pp.210–222 and Jessica Horsley, Der Almanachdes Blauen Reiters als Gesamtkunstwerk. Eineinterdisziplinäre Untersuchung, Peter Lang,Frankfurt/Main et al, 2006.63 Wassily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, Yellow Sound, 1912,Complete Writings on Art, p. 269.64 Wassily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, Yellow Sound, 1912,Complete Writings on Art, pp. 276–277.65 For the Steinerian themes of his oeuvreconsult Washton Long, <strong>Kandinsky</strong>: TheDevelopment of an Abstract Style, pp. 27–28;Claudia Emmert, Bühnenkompositionen undGedichte von Wassily <strong>Kandinsky</strong> im Kontexteschatologischer Lehren seiner Zeit 1896–1914, Peter Lang, Frankfurt/Main et al, 1998.66 Ronald Templeton, “Wassily <strong>Kandinsky</strong> undRudolf Steiner,” Das Goetheanum, vol. 63, no.23, June 3, 1984, p. 179, refers to <strong>Kandinsky</strong>having attended all the Mystery Dramas. Forfurther analogies between these and theThe Yellow Sound, see <strong>Behr</strong>, “<strong>Kandinsky</strong> asPlaywright: the Stage-Compositions 1908–1914,” pp. 114–123.67 Wassily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, “Whither the ‘New’ Art,”1911, Complete Writings on Art, p. 101.68 Washton Long, Kandinky: The Development ofan Abstract Style, pp. 57–61.69 Wassily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, Yellow Sound, 1912,Complete Writings on Art, p. 281.70 Gunther Schuller, “The Case of Thomas deHartmann,” The Yellow Sound, Solomon R.Guggenheim Museum, New York, 1982,unpaginated. Extant score: Thomas deHartmann, Music towards Желтый Звук, 5Kартина, MSS 46, The Thomas de HartmannPapers, Irving S. Gilmore Music Library, YaleUniversity71 Wassily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, “On Stage Composition”,1912, Complete Writings on Art, pp.259–260.72 Ibid., p. 264.73 Hugo Ball letter to Maria Hildebrand-Ball, May27, 1914, Briefe 1911–1927, AnnemarieSchütt-Hennings (ed.), Cologne, 1957, p. 30.74 Hugo Ball, “Das Münchener Künstlertheater.Ein prinzipielle Beleuchtung,” Phöbus, vol. 1,no. 2, May 1914, p. 73.75 Hugo Ball, Letter to Maria Hildebrand-Ball,May 27, 1914, Briefe 1911–1927, pp. 28–32.76 Ibid. p. 29.77 Hugo Ball, “Das Münchener Künstlertheater.Ein prinzipielle Beleuchtung,” p. 73.78 Hugo Ball, Letter to Maria Hildebrand-Ball,June 29, 1914, Briefe 1911–1927, p. 33–34.79 For an English translation of Violet, seeShulamith <strong>Behr</strong>, “<strong>Kandinsky</strong> as Playwright: theStage-Compositions 1908–1914,” vol. 2, pp.20–53.80 Craig, On the Art of the Theatre, p. 146. Atranslation of this treatise was in <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’spossession. E. Gordon Craig, Die Kunst desTheaters, trans. Maurice Magnus, Seemann,Berlin and Leipzig, 1905. <strong>Kandinsky</strong> Archive,Centre Georges Pompidou, Musée nationald’art modern, Paris. Jessica Boissel, “SolcheDinge haben eigene Geschicke: <strong>Kandinsky</strong>und das Experiment ‘Theater,’” exh. cat., DerBlaue Reiter, Kunstmuseum Bern, 1987, p.244 and note 43, clarifies that the book waspart of the possessions of the Munich periodreturned by Münter to <strong>Kandinsky</strong> in Dessau1926.81 Cf. Phillip Mann, Hugo Ball: An IntellectualBiography, London, 1987, p. 37.82 Richard Sheppard, “<strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s oeuvre1900–1914: the Avant-Garde as Rear-Guard,” Word and Image, vol. 6, no. 1,Jan-March 1990, pp. 53–55.83 For the pre-1914 context, consult Shulamith<strong>Behr</strong>, “Deciphering Wassily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’s Violet:Activist Expressionism and the RussianSlavonic Milieu,” in Expressionism Reassessed,eds. Shulamith <strong>Behr</strong>, David Fanning andDouglas Jarman, Manchester UniversityPress, Manchester, 1993, pp. 171–188.84 Wassily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, “aus violett, romantischesbühnenstück von <strong>Kandinsky</strong>,” bauhaus , no. 3,1927, p. 6.85 On Schlemmer consult Juliet Koss, “BauhausTheatre and Human Dolls,” The Art Bulletin,vol. 85, no. 4, Dec, 2003, pp. 724–745.86 Helmut Friedel and Marion Ackermann, “AColorful Life. The History of Vasily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>’sWork in the Lenbachhaus,” in exh. cat. Vasily<strong>Kandinsky</strong>. A Colorful Life, Städtische Galerieim Lenbachhaus, Munich, 1995, pp. 15–31.87 Wassily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, Complete Writings, p. 749.88 Wassily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, “Über die abstrakteBühnensynthese,” Buch Staatliches Bauhausin Weimar 1919–23, Karl Nierendorf (ed.),Weimar and Cologne, 1923; in <strong>Kandinsky</strong>—Essays über Kunst und Künstler, Max Bill (ed.),Gerd Hatje, Stuttgart, 1955, pp. 69–73.89 Wassily <strong>Kandinsky</strong>, “Über die abstrakteBühnensynthese,”: “Alle Augen in einerRichtung, alle Ohren zu einer Quelle.”90 Walter Benjamin, Charles Baudelaire: A LyricPoet in the Era of High Capitalism, trans. HarryZohn,Verso, London, 1972, p. 126.91 Theodor Adorno, In Search of Wagner, Verso,London, 1981, pp. 102–104.92 Juliet Koss, Modernism after Wagner, p. xiii.84 shulamith behr<strong>Kandinsky</strong> and Theater 85