Managing Municipal Marine Capture Fisheries in ... - Oneocean.org

Managing Municipal Marine Capture Fisheries in ... - Oneocean.org

Managing Municipal Marine Capture Fisheries in ... - Oneocean.org

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

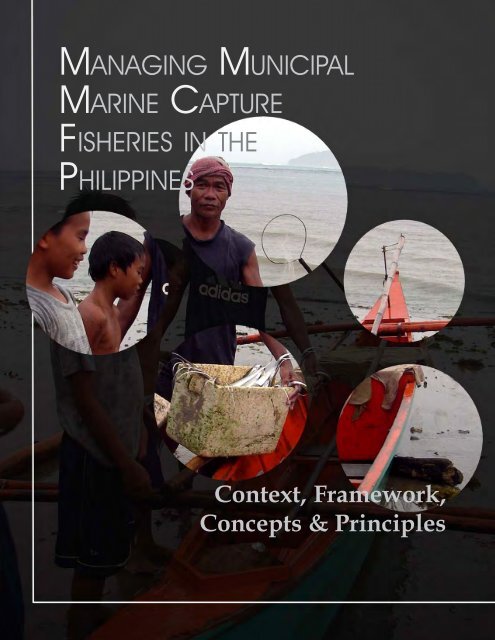

<strong>Manag<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Municipal</strong> <strong>Mar<strong>in</strong>e</strong> <strong>Capture</strong> <strong>Fisheries</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Philipp<strong>in</strong>es:Context, Framework, Concepts & Pr<strong>in</strong>ciplesBy Department of Agriculture-Bureau of <strong>Fisheries</strong> and Aquatic Resources (DA-BFAR)2010Pr<strong>in</strong>ted <strong>in</strong> Cebu City, Philipp<strong>in</strong>esCitation:Department of Agriculture-Bureau of <strong>Fisheries</strong> and Aquatic Resources (DA-BFAR). 2010. <strong>Manag<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Municipal</strong><strong>Fisheries</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Philipp<strong>in</strong>es: Context, Framework, Concepts and Pr<strong>in</strong>ciples. <strong>Fisheries</strong> Improved for Susta<strong>in</strong>ableHarvest (FISH) Project, Cebu City, Philipp<strong>in</strong>es.This publication was made possible through support provided by the <strong>Fisheries</strong> Improved for Susta<strong>in</strong>ableHarvest (FISH) Project of the Department of Agriculture-Bureau of <strong>Fisheries</strong> and Aquatic Resources (DA-BFAR) and the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID)under the terms and conditions of USAID Contract Nos. AID-492-C-00-96-00028-00 and AID-492-C-00-03-00022-00. The op<strong>in</strong>ions expressed here<strong>in</strong> are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views ofthe USAID. This publication may be reproduced or quoted <strong>in</strong> other publications as long as proper referenceis made to the source.Authors: Nygiel Armada; Reg<strong>in</strong>a BacalsoEditor: Asuncion Sia, Rebecca P. SmithLayout & Graphics: Leslie T<strong>in</strong>apay, Asuncion SiaIllustrations & Cartoons: Amiel Roberto Jude Rufo, Asuncion Sia, Leslie T<strong>in</strong>apayAdm<strong>in</strong>istrative Support: Glocel Ortega, Ella Melendez, Rodrigo PojasCover Photo: Fisher and sons at Buenavista, Tandag, Surigao del Sur (Asuncion Sia, 2008)FIRST EDITION2010FISH Document No. xx-FISH/2010

MANAGING MUNICIPAL MARINE CAPTURE FISHERIES IN THE PHILIPPINES: Context, Framework, Concepts and Pr<strong>in</strong>ciplesiv

PREFACEPrefaceDo you work with or <strong>in</strong> local government and communities to managemunicipal fisheries?Are you concerned that <strong>in</strong> the not-so-distant future we may not haveany fish left to eat?Would you like to help make fisheries susta<strong>in</strong>able?If you answered ‘yes’ to any of the above questions, this Sourcebook was written especially for you. It wasproduced as an offshoot of the implementation of the <strong>Fisheries</strong> Improved for Susta<strong>in</strong>able Harvest (FISH)Project of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the Philipp<strong>in</strong>es’ Department ofAgriculture-Bureau of <strong>Fisheries</strong> and Aquatic Resources (DA-BFAR). In the course of carry<strong>in</strong>g out the FISHProject, we have worked with countless <strong>in</strong>dividuals <strong>in</strong> local government, non-governmental <strong>org</strong>anizations(NGOs) and the fish<strong>in</strong>g communities toward establish<strong>in</strong>g an ecosystem-based fisheries management system <strong>in</strong>each of the four areas where we operate — Calamianes Group of Islands, Palawan; Danajon Bank, Bohol;Lanuza Bay, Surigao del Sur; and Tawi-Tawi Bay, Tawi-Tawi. Deeply concerned about poor fish catches andhigh fish prices, these government and non-governmental <strong>org</strong>anization (NGO) workers and communitymembers have been keen students of fisheries management, eagerly absorb<strong>in</strong>g the knowledge and skills thatwe have to share, and ask<strong>in</strong>g endless questions about the practical aspects of manag<strong>in</strong>g their fishery resources.Given Project limitations, it was not been possible for us to be present <strong>in</strong> all sites at all times to addressall their concerns and questions. So we did the next best th<strong>in</strong>g: We produced this Sourcebook to provide areadily available source of <strong>in</strong>formation to municipal fisheries managers and stakeholders everywhere,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g those outside the FISH Project sites that we were unable to directly assist.This Sourcebook conta<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong>formation drawn from past experience <strong>in</strong> coastal and fisheries resourcemanagement <strong>in</strong> the Philipp<strong>in</strong>es, particularly experiences and lessons from the FISH Project and anotherUSAID-supported project, the Coastal Resource Management Project (CRMP) of the Department ofEnvironment and Natural Resources (DENR). Additional sources <strong>in</strong>clude documents from the UN Food andAgriculture Organization (UN-FAO), San Miguel Bay Project (ICLARM [WorldFish Center]), Visayan SeaProject (Deutsche Gesselschaft für Technische Zussamenarbeit [GTZ]), Fishery Sector Program 1 and 2 (AsianDevelopment Bank [ADB]), and <strong>Fisheries</strong> Resources Management Project (ADB).<strong>Fisheries</strong> tra<strong>in</strong>ers, law enforcers, policymakers, researchers and students can also benefit from thisSourcebook. Indeed, if you are <strong>in</strong>volved or have any <strong>in</strong>terest at all <strong>in</strong> support<strong>in</strong>g susta<strong>in</strong>able fisheries <strong>in</strong> thePhilipp<strong>in</strong>es and want to know how it can be done, the Sourcebook is for you. Through the Sourcebook, we hopeto provide you with the knowledge that will help you <strong>in</strong> your work as a manager or steward of yourcommunity’s coastal and fishery resources, or as an advocate of susta<strong>in</strong>able fisheries.Only a small number of pr<strong>in</strong>t copies of this Sourcebook have been produced, mostly for our nationaland local government partners. But anyone <strong>in</strong>terested can get a copy, as we will make Sourcebook available <strong>in</strong>electronic (pdf) format, freely downloadable from our web site at http://oneocean.<strong>org</strong>/download/.v

MANAGING MUNICIPAL MARINE CAPTURE FISHERIES IN THE PHILIPPINES: Context, Framework, Concepts and Pr<strong>in</strong>ciplesvi

MANAGING MUNICIPAL MARINE CAPTURE FISHERIES IN THE PHILIPPINES: Context, Framework, Concepts and Pr<strong>in</strong>ciplesviii

Table of ContentsTABLE OF CONTENTSPreface ..........................................................................................................................................Foreword ......................................................................................................................................List of Figures & TablesFigures & Pictures ..........................................................................................................Tables................................................................................................................................vviixvxviiChapter 1 – Introduction ......................................................................................................... 1What This Sourcebook Is About .................................................................................... 1What You Can (And Cannot) F<strong>in</strong>d In This Sourcebook............................................. 2How To Use This Sourcebook ........................................................................................ 2Just Learn<strong>in</strong>g, Essentially ............................................................................................. 3Follow These Road Signs .............................................................................................. 4Chapter 2 – Background & Rationale .................................................................................. 5Are We The Generation To Fish The Last Fish?........................................................ 6More Hard Facts ............................................................................................................. 7Wisdom In H<strong>in</strong>dsight .................................................................................................... 7Facts Of (Fish) Life ......................................................................................................... 10Water Matters ................................................................................................................. 11The Oceans In Depth .................................................................................................... 12In The Water ............................................................................................................ 12On The Seafloor ....................................................................................................... 13A Question Of Productivity ......................................................................................... 15Benthic Life ............................................................................................................... 15The Dark Zone.......................................................................................................... 16The Light Zone ......................................................................................................... 16Where The Fish Are................................................................................................. 17Food Cha<strong>in</strong>s & Food Webs ........................................................................................... 18Th<strong>in</strong>k Ecosystem ............................................................................................................ 20The Mangrove Ecosystem ...................................................................................... 21The Seagrass Ecosystem ......................................................................................... 22The Coral Reef Ecosystem ...................................................................................... 23Interactive Systems ................................................................................................. 25When A L<strong>in</strong>k Breaks ...................................................................................................... 26The Human Factor ................................................................................................... 28So Let’s Talk About Fish ............................................................................................... 29A Liv<strong>in</strong>g Resource ................................................................................................... 30Life In The Sea (As We Know It) ................................................................................ 31It’s All About Survival............................................................................................ 31ix

MANAGING MUNICIPAL MARINE CAPTURE FISHERIES IN THE PHILIPPINES: Context, Framework, Concepts and Pr<strong>in</strong>ciplesSpawn<strong>in</strong>g Patterns ........................................................................................... 35Surplus Production ................................................................................................. 36What About Fish<strong>in</strong>g ...................................................................................................... 36Russell’s Axiom........................................................................................................ 38Age-Size Effects ....................................................................................................... 40Ecosystem Effects .................................................................................................... 42Fish<strong>in</strong>g Down The Food Web ................................................................................ 43Dissect<strong>in</strong>g Overfish<strong>in</strong>g .................................................................................................. 44Can Fish<strong>in</strong>g Be Susta<strong>in</strong>able? ......................................................................................... 47Regulate, Regulate, Regulate ................................................................................. 48No reason for <strong>in</strong>action ...................................................................................... 50Control mechanisms ......................................................................................... 51Habitat protection ............................................................................................. 53More Than Fish<strong>in</strong>g ......................................................................................................... 55Review .............................................................................................................................. 55Additional References ................................................................................................... 57Chapter 3 – Legal & Policy Framework ................................................................................. 59A Fundamental Mandate .............................................................................................. 60The Rise Of Local Autonomy ....................................................................................... 62Def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g The Job............................................................................................................. 64Lay<strong>in</strong>g The Groundwork For <strong>Fisheries</strong> Management.............................................. 66The NIPAS Act ......................................................................................................... 66The AFMA ................................................................................................................ 67The <strong>Fisheries</strong> Code .................................................................................................. 68National Policy Dictates Susta<strong>in</strong>able <strong>Fisheries</strong> ......................................................... 68Areas Of Jurisdiction ............................................................................................... 69Promot<strong>in</strong>g Participatory Management ................................................................ 72Fish<strong>in</strong>g By The Code ...................................................................................................... 74What’s The Catch? ................................................................................................... 75Gear Checks & Other Input Control ..................................................................... 77Limits On Fish Culture ........................................................................................... 79Habitat Protection.................................................................................................... 83…& A Few More ...................................................................................................... 85Count<strong>in</strong>g On BFAR ........................................................................................................ 86It’s All About Responsible, Susta<strong>in</strong>able Use.............................................................. 87Who Else Are On Our Team? ....................................................................................... 91Department of Environment & Natural Resources ........................................... 92Department of the Interior & Local Government ............................................. 93Department of Transportation & Communication ............................................ 94Department of Science & Technology .................................................................. 95Other Assist<strong>in</strong>g Organizations .............................................................................. 96Emerg<strong>in</strong>g Institutional Arrangements For ICM ................................................. 96Review .............................................................................................................................. 97Additional References ................................................................................................... 101x

TABLE OF CONTENTSChapter 4 – The Ecosystem Approach ................................................................................. 103EAF Spelled Out ............................................................................................................. 104Balanc<strong>in</strong>g Diverse Objectives ................................................................................ 105Cover<strong>in</strong>g All Grounds ............................................................................................ 106An Integrated Approach ........................................................................................ 108Sett<strong>in</strong>g Boundaries................................................................................................... 109Guid<strong>in</strong>g EAF ................................................................................................................... 111The <strong>Fisheries</strong> Management Process ...................................................................... 111Biological & Environmental Concepts & Constra<strong>in</strong>ts ....................................... 112Technological Considerations ............................................................................... 112Social & Economic Dimensions ............................................................................. 113Institutional Concepts & Functions ...................................................................... 113Time Scales................................................................................................................ 114Precautionary Approach ........................................................................................ 114Special Requirements For Develop<strong>in</strong>g Countries .............................................. 114No Dearth Of Options ................................................................................................... 115Technical Measures ................................................................................................. 115Input & Output Controls ........................................................................................ 117Ecosystem Manipulation ........................................................................................ 118Rights-Based Management Approaches .............................................................. 119EAF Concerns Beyond Fish<strong>in</strong>g .................................................................................... 120Review.............................................................................................................................. 120Additional References................................................................................................... 123Chapter 5 – Plann<strong>in</strong>g & Implementation Framework ........................................................ 125About ICM ....................................................................................................................... 126Plann<strong>in</strong>g Coastal Management ............................................................................. 127The Plann<strong>in</strong>g Process .............................................................................................. 129A Non-L<strong>in</strong>ear Process ............................................................................................. 130Plann<strong>in</strong>g For Susta<strong>in</strong>able <strong>Municipal</strong> <strong>Fisheries</strong> .......................................................... 132Inform<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Fisheries</strong> Management Under EAF ................................................... 134Phase 1: Issue Identification & Basel<strong>in</strong>e Assessment ........................................ 135Prelim<strong>in</strong>ary determ<strong>in</strong>ation of management area ........................................ 135Identification of broad fishery issues ............................................................ 138Background <strong>in</strong>formation compilation, analysis & basel<strong>in</strong>e assessment .. 141Phase 2: Plan Preparation & Adoption ....................................................................... 144Sett<strong>in</strong>g objectives & <strong>in</strong>dicators .............................................................................. 145Formulat<strong>in</strong>g rules .................................................................................................... 154The plan ..................................................................................................................... 156Phase 3: Action Plan & Project Implementation ....................................................... 158Phase 4: Monitor<strong>in</strong>g & Evaluation .............................................................................. 159Phase 5: Information Management, Education & Outreach ................................... 160Review .............................................................................................................................. 162Additional References ................................................................................................... 167xi

MANAGING MUNICIPAL MARINE CAPTURE FISHERIES IN THE PHILIPPINES: Context, Framework, Concepts and Pr<strong>in</strong>ciplesChapter 6 – Mak<strong>in</strong>g It Happen .............................................................................................. 169Appendices1 – Impacts Of Human Activities On The Coastal Zone ....................................... 175Illegal Activities ................................................................................................. 175Fish<strong>in</strong>g ................................................................................................................. 176Aquaculture Development ............................................................................. 177Foreshore Land Use And Development ....................................................... 177Coastal Habitat Conversion And Land Fill<strong>in</strong>g ........................................... 177M<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g And Quarry<strong>in</strong>g ................................................................................... 178Tourism Development ..................................................................................... 1782 – Various Aquaculture Systems, Their Impacts & Benefits ............................... 1793 – Develop<strong>in</strong>g A Framework For Economic Analysis Of CRM Investments:The Case Of Ubay, Bohol ...................................................................................... 180Introduction ....................................................................................................... 180Ubay CRM Plan & Implementation.............................................................. 181Framework For Analysis ................................................................................. 182Economic Analysis ..................................................................................... 183F<strong>in</strong>ancial Analysis ...................................................................................... 186Weaknesses of the Framework ................................................................ 186Pilot-Test<strong>in</strong>g Results For Ubay ....................................................................... 187Economic Analysis ..................................................................................... 187F<strong>in</strong>ancial Analysis ...................................................................................... 193Data Requirements & Gaps ............................................................................ 197Conclusion & Further Steps ........................................................................... 1984 – DA-BFAR List Of Rare, Threatened & Endangered Species .......................... 199Rare Species ....................................................................................................... 199Threatened Species ........................................................................................... 199Endangered Species ......................................................................................... 200Corals .................................................................................................................. 2015 – Highlights Of The UN-FAO Code Of Conduct For Responsible <strong>Fisheries</strong>2026 – Coastal Management Phases & Steps As A Basic LGU Service& The Roles Of Various Sectors ........................................................................... 2047 – Data Requirements & Use Relevant To <strong>Fisheries</strong> ManagementPlann<strong>in</strong>g At The LGU Level .................................................................................. 208General Considerations In The Collection & Provision Of Data& Information For <strong>Fisheries</strong> Management .................................................. 208Data Requirements & Use Relevant To The FormulationOf A <strong>Fisheries</strong> Management Plan .................................................................. 209Data Requirements & Use <strong>in</strong> the Determ<strong>in</strong>ation of ManagementActions & Monitor<strong>in</strong>g Performance.............................................................. 2148 – L<strong>in</strong>kages Between Some Basic Data Requirements, Indicators(Suggested Examples) & Operational Objectives For AHypothetical Fishery............................................................................................... 218xii

TABLE OF CONTENTSReferencesWorks Cited .................................................................................................................... 223Consolidated List of Additional References Provided With This Sourcebook orAvailable From Web Sources ................................................................................ 231Acronyms & Abbreviations .................................................................................................... 233Glossary ....................................................................................................................................... 237xiii

MANAGING MUNICIPAL MARINE CAPTURE FISHERIES IN THE PHILIPPINES: Context, Framework, Concepts and Pr<strong>in</strong>ciplesxiv

MANAGING MUNICIPAL MARINE CAPTURE FISHERIES IN THE PHILIPPINES: Context, Framework, Concepts and Pr<strong>in</strong>ciples3.6. Fish farm<strong>in</strong>g limits ............................................................................................... 813.7. MPAs: Microcosm of participatory management ........................................... 843.8. Management of Red-listed species and the LGU’s role ................................. 893.9. DENR’s technical assistance role ....................................................................... 933.10. Jo<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g forces aga<strong>in</strong>st illegal fish<strong>in</strong>g ................................................................. 943.11. Emerg<strong>in</strong>g public-private sector coastal management functions <strong>in</strong> thePhilipp<strong>in</strong>es............................................................................................................. 973.12. Government agencies with authority and jurisdiction over the coastal zone 974.1. <strong>Municipal</strong> waters for municipal fishers ........................................................... 1054.2. Fishery <strong>in</strong>teractions <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> an exploited ecosystem ............................. 1074.3. Proposed fishery management unit map with 25 nautical mile offsetfrom shore ............................................................................................................. 1104.4. Restor<strong>in</strong>g mangroves ........................................................................................... 1124.5. Stakeholder participation.................................................................................... 1134.6 Mak<strong>in</strong>g gear ecosystem-friendly ....................................................................... 1164.7. Control mechanisms ............................................................................................ 1184.8. Access rights ......................................................................................................... 1195.1. Impacts of human activities on the coastal zone ............................................ 1275.2. CRM plann<strong>in</strong>g cycle adapted for Philipp<strong>in</strong>e LGUs ....................................... 1285.3. CRM scope and context ....................................................................................... 1295.4. Major players <strong>in</strong> coastal management <strong>in</strong> the Philipp<strong>in</strong>es ............................. 1315.5. <strong>Fisheries</strong> management under EAF based on the Philipp<strong>in</strong>e CRMplann<strong>in</strong>g process .................................................................................................. 1335.6. <strong>Fisheries</strong> management under EAF based on the Philipp<strong>in</strong>e CRMplann<strong>in</strong>g process, Phase 1 ................................................................................... 1365.7. Fishers’ registration ............................................................................................. 1375.8. Address<strong>in</strong>g the need for an ecosystem viewpo<strong>in</strong>t ......................................... 1385.9. Hierarchical tree framework for identification of fishery resources ........... 1405.10. <strong>Fisheries</strong> management under EAF based on the Philipp<strong>in</strong>e CRMplann<strong>in</strong>g process, Phase 2 .................................................................................. 1445.11. Keep<strong>in</strong>g stakeholders <strong>in</strong>formed......................................................................... 1465.12. Qualitative risk assessment ................................................................................ 1515.13. Indicators, reference po<strong>in</strong>ts and performance measures............................... 1535.14. Adaptive management plann<strong>in</strong>g cycle............................................................. 1555.15. <strong>Fisheries</strong> management under EAF based on the Philipp<strong>in</strong>e CRMplann<strong>in</strong>g process, Phase 3 ................................................................................... 1585.16. <strong>Fisheries</strong> management under EAF based on the Philipp<strong>in</strong>e CRMplann<strong>in</strong>g process, Phase 4 ................................................................................... 1595.17. <strong>Fisheries</strong> management under EAF based on the Philipp<strong>in</strong>e CRMplann<strong>in</strong>g process, Phase 5 ................................................................................... 1616.1. Why keep records................................................................................................. 172A1.1. Fish yield decl<strong>in</strong>e and loss on a destroyed and recover<strong>in</strong>g coral reefover 10 years ......................................................................................................... 176xvi

LIST OF TABLES & FIGURESTables3.1. Provisions <strong>in</strong> the 1991 Local Government Code that def<strong>in</strong>e the LGU’sduties and functions <strong>in</strong> fisheries and environmental management ............ 653.2. <strong>Fisheries</strong> Code provisions prescrib<strong>in</strong>g output controls ................................. 743.3. <strong>Fisheries</strong> Code provisions prescrib<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>put controls ................................... 763.4. LGU role <strong>in</strong> wildlife conservation and protection under RA 9147’sdraft IRR as of 28 September 2009 ..................................................................... 905.1 Core ICM guidel<strong>in</strong>es ............................................................................................ 1285.2. The five phases <strong>in</strong> the CRM plann<strong>in</strong>g process adapted for Philipp<strong>in</strong>e LGUs 1305.3. Information requirements of fisheries management under EAF ................. 1345.4. Some basic data requirements for <strong>in</strong>form<strong>in</strong>g fisheries management .......... 1425.5. Information generated by a full assessment of a fish stock .......................... 1425.6. Example contents of a simple fishery profile .................................................. 1435.7. General strategies to address common problems <strong>in</strong> Philipp<strong>in</strong>e municipalfisheries .................................................................................................................. 1565.8. Suggested elements for a fisheries management plan under EAF .............. 157A3.1. Estimated annual land<strong>in</strong>gs of fish catch <strong>in</strong> Ubay, 2004-08......................... 188A3.2. Increase <strong>in</strong> municipal fish catch from legal gear, based on annualland<strong>in</strong>gs, Ubay, Bohol, 2004-08 ........................................................................ 189A3.3. Fish bought by fish broker <strong>in</strong> Humayhumay, Bohol, 2007-08 .................... 189A3.4. Blast fish<strong>in</strong>g damages avoided, Ubay, Bohol, 2004-08 ................................ 190A3.5. Illegal fish<strong>in</strong>g damages avoided, Ubay, Bohol, 2004-08 .............................. 190A3.6. Increased coral cover, Danajon Bank, 2004-06 ............................................. 191A3.7. Value of MPA benefits, Ubay, Bohol, 2004-08 .............................................. 191A3.8. Damages avoided by reduc<strong>in</strong>g commercial fish<strong>in</strong>g encroachment onmunicipal waters, Ubay, Bohol, 2004-08 ........................................................ 191A3.9. Summary of annual economic benefits from enforcement, Ubay, Bohol,2004-08................................................................................................................... 192A3.10. Costs of enforc<strong>in</strong>g CRM rules and regulations, Ubay, Bohol, 2004-07 .... 193A3.11. Costs of enforc<strong>in</strong>g CRM rules and regulations, Ubay, Bohol, 2008 .......... 194A3.12. Net annual benefits from CRM <strong>in</strong>vestments, 2004-08 ................................. 194A3.13. Current revenues from CRM-related activities, Ubay, Bohol, 2004-08 .... 195A3.14. Current net <strong>in</strong>come from CRM-related activities, Ubay, Bohol, 2004-08 195A3.15. Potential additional LGU revenues from CRM activities, Ubay, Bohol,<strong>in</strong> Php ..................................................................................................................... 196A3.16. Current and potential net <strong>in</strong>come from CRM activities, Ubay, Bohol,<strong>in</strong> Php ..................................................................................................................... 196A7.1. Desirable Data & Information Requirements for <strong>Fisheries</strong> for theFormulation & Implementation of Management Plans ............................... 210xvii

MANAGING MUNICIPAL MARINE CAPTURE FISHERIES IN THE PHILIPPINES: Context, Framework, Concepts and Pr<strong>in</strong>ciplesxviii

Chapter 1: INTRODUCTIONChapter 1IntroductionIn This Chapter‣Know what this Sourcebook is about‣Get a sneak peek of the chapters ahead‣F<strong>in</strong>d out how you can get the most out of this SourcebookIf the only tool you have is a hammer,you tend to see every problem as a nail.— Abraham Maslow, Father of Humanistic PsychologyAs a fisheries manager, your first order of bus<strong>in</strong>ess is to understand what it isthat you are tasked to manage and know what your action choices are. ThisSourcebook gives you the basic th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g tools to better study what is go<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>in</strong> yourfisheries and what your options may be, and guide you to the best practical course of action.WHAT THIS SOURCEBOOK IS ABOUTThis Sourcebook conta<strong>in</strong>s what its title says it does: the context, framework, conceptsand pr<strong>in</strong>ciples of municipal fisheries <strong>in</strong> the Philipp<strong>in</strong>es. We look <strong>in</strong>to the current state of ourfisheries, and look back to the past for understand<strong>in</strong>g on how we got here. We lightly1

MANAGING MUNICIPAL MARINE CAPTURE FISHERIES IN THE PHILIPPINES: Context, Framework, Concepts and Pr<strong>in</strong>ciplesexplore fisheries science for clues on why fisheries are the way they are and how theywould be <strong>in</strong> an ideal world. We exam<strong>in</strong>e Philipp<strong>in</strong>e policy and make the case for a change<strong>in</strong> the country’s current exploitation policies and patterns toward more susta<strong>in</strong>ablepractices. And we survey our social and political landscape and encourage thestrengthen<strong>in</strong>g of fisheries management capacities at all levels of government and society.WHAT YOU CAN (AND CANNOT) FIND IN THIS SOURCEBOOK<strong>Fisheries</strong> science is so cram full of <strong>in</strong>formation that it can overwhelm. While thisSourcebook <strong>in</strong>cludes more theory than you will f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>in</strong> the rest of the Handbook Series, don’texpect it to be a def<strong>in</strong>itive reference on fisheries management theory — we figured wewould do you a favor by leav<strong>in</strong>g out those theoretical details that make for <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>gacademic study but are not particularly relevant or immediately useful to practical action.Expect, <strong>in</strong>stead, to f<strong>in</strong>d much <strong>in</strong>formation with direct application to your work, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>ganswers to such questions as:1. Why must fisheries be managed?2. What assumptions, concepts, values and practices go <strong>in</strong>to manag<strong>in</strong>g fisheries?3. What is the local government’s role <strong>in</strong> fisheries?4. What strategy or approach is recommended?5. What else can we do to do th<strong>in</strong>gs better?Because our ma<strong>in</strong> focus is on municipal mar<strong>in</strong>e capture fisheries, any reference tothe other sectors (commercial and aquaculture) will only be <strong>in</strong> relation to municipalmar<strong>in</strong>e capture fisheries.HOW TO USE THIS SOURCEBOOKThis Sourcebook is an important resource not only for fisheries managers, but alsofor those <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> advocacy, tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and public education. It comes with a CDsupplement that conta<strong>in</strong>s important resources for municipal fisheries managementtra<strong>in</strong>ers.The next chapters are <strong>org</strong>anized <strong>in</strong> such a way that each part builds on the<strong>in</strong>formation that comes before it. But while best read sequentially, the various parts areself-conta<strong>in</strong>ed enough to allow you to jump to any topic that meets your current <strong>in</strong>terestsor work requirements. Bolded words or phrases <strong>in</strong> the body text are also expla<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> theGlossary.Chapter 2 — Background & RationaleHere you will f<strong>in</strong>d the many important social, economic and natural reasons formanag<strong>in</strong>g fisheries, as well as an overview of your management options and an analyticallook at overfish<strong>in</strong>g and susta<strong>in</strong>able fish<strong>in</strong>g.Chapter 3 — Legal & Policy FrameworkThis chapter focuses on the laws and policies govern<strong>in</strong>g municipal fisheries, <strong>in</strong>particular those provisions of the 1998 Philipp<strong>in</strong>e <strong>Fisheries</strong> Code (Republic Act [RA] No.8550) that are relevant to municipal fisheries. It also <strong>in</strong>cludes a discussion on other2

Chapter 1: INTRODUCTIONpert<strong>in</strong>ent laws and policies, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>ternational agreements to which the Philipp<strong>in</strong>esis a party, and po<strong>in</strong>ts out the national policy to use <strong>in</strong>tegrated coastal management (ICM)as the preferred strategy.Chapter 4 — The Ecosystem ApproachIn this chapter, we will <strong>in</strong>troduce a management strategy that, accord<strong>in</strong>g toemerg<strong>in</strong>g expert consensus, must be <strong>in</strong>tegrated <strong>in</strong>to current coastal management systems:the ecosystem approach to fisheries (EAF). Here you will see what we mean when we say“ecosystem approach,” and what ecosystem considerations must be addressed bymunicipal fisheries management.Chapter 5 — Plann<strong>in</strong>g & Implementation FrameworkThis is where you will get your first good view (if only just an overview) of theplann<strong>in</strong>g and management process that has been shown to work well for municipalfisheries <strong>in</strong> the Philipp<strong>in</strong>es. This process is anchored on a participatory local governmentdrivenCRM plann<strong>in</strong>g process now used widely <strong>in</strong> the Philipp<strong>in</strong>es, and <strong>in</strong>corporatescurrent best practices and many of the pr<strong>in</strong>ciples of EAF.Chapter 6 — Mak<strong>in</strong>g It HappenHere we look <strong>in</strong>to what fisheries managers can do to jumpstart the fisheriesmanagement plann<strong>in</strong>g process, and what other actions must be taken <strong>in</strong> the near andmedium-term by responsible authorities to properly <strong>in</strong>tegrate EAF <strong>in</strong> the CRM plann<strong>in</strong>gprocess that has been adopted by many local government units (LGUs).Additional <strong>in</strong>formation, mean<strong>in</strong>gs of acronyms and abbreviations, anddef<strong>in</strong>itions of hard-to-avoid technical terms are provided <strong>in</strong> the last sections of this book.Some of these <strong>in</strong>formation and terms are used <strong>in</strong> the specific context of Philipp<strong>in</strong>efisheries, so make liberal use of these sections:AppendicesAcronyms & AbbreviationsGlossaryJUST LEARNING, ESSENTIALLY<strong>Fisheries</strong> science and policy, no matter how basic, are not light subject matters toread, so you will need to give them some serious focus and attention. Still, this Sourcebookis designed and <strong>org</strong>anized <strong>in</strong> a way that should make for, if not entirely easy read<strong>in</strong>g, atleast an <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g learn<strong>in</strong>g experience. So make the most out of it — put on your th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>gcap, enjoy a good read, and learn!3

MANAGING MUNICIPAL MARINE CAPTURE FISHERIES IN THE PHILIPPINES: Context, Framework, Concepts and Pr<strong>in</strong>ciplesFOLLOW THESE ROAD SIGNSWe will make extensive use of icons to help you f<strong>in</strong>d important stuff easily <strong>in</strong> eachhandbook and throughout the Sourcebook, like road signs do. Each of the follow<strong>in</strong>g iconswill call your attention to some essential <strong>in</strong>formation:Tip Icon – handy <strong>in</strong>formation to take on the road to help you <strong>in</strong> your work as a fisheriesmanagerRemember Icon – important stuff to keep <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d, for example, (when choos<strong>in</strong>g a site for amar<strong>in</strong>e protected area) “Talk to the old folks!”Five-Step or Five-Phase Icon – rem<strong>in</strong>ds readers of the five key steps (or phases) of the coastalresource management process: Early Plann<strong>in</strong>g and Commitment (Issue Identification andBasel<strong>in</strong>e Assessment), Plan Preparation and Adoption, Action Plann<strong>in</strong>g and PlanImplementation, Monitor<strong>in</strong>g and Evaluation, and Policy Development and Information,Education and CommunicationTime Icon – <strong>in</strong>dicates recommended frequency, prescribed timeframe, or “best time of year/week/day” to <strong>in</strong>itiate/complete an actionIEC/Policy Icon – tells readers to consider IEC or policy support for a management actionInformation Icon – tells readers to refer to another section for more <strong>in</strong>formation on a boldeditem <strong>in</strong> the body textChecklist Icon – rem<strong>in</strong>ds readers to go through a to-do or to-have list.Caution Icon – warns readers of a pitfall they must avoid4

Chapter 2: BACKGROUND & RATIONALEChapter 2Background & RationaleIn This Chapter‣Take a hard look at our fisheries and how we got to thecurrent critical level of resource degradation.‣Exam<strong>in</strong>e both human history and natural history for guidanceon how we can do th<strong>in</strong>gs better‣Look <strong>in</strong>to the effects of fish<strong>in</strong>g on fish populations‣See the difference between exploitative and susta<strong>in</strong>able fish<strong>in</strong>gHistory is a vast early warn<strong>in</strong>g system— Norman Cous<strong>in</strong>s, Political JournalistFor the longest time, we regarded the sea as so vast and bottomless as tobe <strong>in</strong>exhaustible, impenetrable and totally resistant to any but the most catastrophicevent. Now, <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly, we are learn<strong>in</strong>g that it is <strong>in</strong> fact a very delicate system, vulnerableto m<strong>in</strong>ute changes <strong>in</strong> the environment, even those that happen thousands of kilometers,perhaps even light years, away. Hav<strong>in</strong>g progressively exploited and degraded our mar<strong>in</strong>eresources decade after decade, we are wak<strong>in</strong>g up to the harsh reality that virtually all of ourmajor fish<strong>in</strong>g grounds have become depleted, no longer the reliable source of food and<strong>in</strong>come that we used to know.5

MANAGING MUNICIPAL MARINE CAPTURE FISHERIES IN THE PHILIPPINES: Context, Framework, Concepts and Pr<strong>in</strong>ciplesThe good news is, the sea is reasonably resilient. With<strong>in</strong> limits, it can and has beenshown to recover from various stresses, both natural and man-made. We don’t know allthere is to know about the processes and <strong>in</strong>teractions that occur <strong>in</strong> and impact the sea, butwe know enough to know that we can manage some of the stresses to mitigate their impacts,specifically (at least for our purpose), on the susta<strong>in</strong>ability and viability of our municipalfisheries. Indeed, this is what fisheries managers are expected to do.Our goal <strong>in</strong> fisheries management is not to stop fish<strong>in</strong>g, but to stop fish<strong>in</strong>g frombe<strong>in</strong>g destructive, excessive and wasteful. Our goal is susta<strong>in</strong>able fish<strong>in</strong>g. As a fisheriesmanager, you will be confronted with many management dilemmas, some of them not evendirectly related to, but still impact<strong>in</strong>g, fisheries. To be effective, you must understand howthe sea works, what we’re do<strong>in</strong>g to it, and what we can do to protect, manage and improveit.This chapter offers you perhaps the most important tool with which to tackle yourwork challenges: an understand<strong>in</strong>g of the dynamics of fisheries, particularly how the forcesand processes that occur naturally <strong>in</strong> the sea are changed by fish<strong>in</strong>g and other humanactivities, and how this ultimately impacts the various fisheries and their viability. Armedwith such understand<strong>in</strong>g, you should be able to anticipate, adapt to, respond <strong>in</strong> a timelyand appropriate manner, and hopefully avoid most potential problems <strong>in</strong> the fisheries youare tasked to manage.ARE WE THE GENERATION TO FISH THE LAST FISH? GlossaryConsider this:• Most of the world’s stocks of the top 10 commercially valuable fish species, whichaccount for about 30% of the world’s fish catch, are fully exploited. (FAO, 2009)• More than 75% of world fish stocks are reported to have been fully exploited,overexploited or depleted. (FAO, 2007)• Extensive loss of biodiversity along coasts has been recorded s<strong>in</strong>ce 1800, with thecollapse of about 40% of species; about one-third of once viable coastal fisheries arenow useless. (Worm et al, 2006. In: Stanford Report, 2006)• From 1950, catch records from the open ocean show widespread decl<strong>in</strong>e of fisheries,with the rate of decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g; <strong>in</strong> 2004, 29% of fisheries were collapsed. (Wormet al, 2006. In: Stanford Report, 2006)• By some estimates, if current trends cont<strong>in</strong>ue, there will be noth<strong>in</strong>g left to fish fromthe sea by the middle of this century. (Worm et al, 2006. In: Stanford Report, 2006) GlossaryAnd here’s what we know of the Philipp<strong>in</strong>e fisheries situation:• Our various types of fishery resources are all biologically overfished, often severely<strong>in</strong> traditional fish<strong>in</strong>g grounds and nearshore areas (Luna et al, 2004).• In the 1980s, fish<strong>in</strong>g effort <strong>in</strong> pelagic fisheries reached twice the magnitudenecessary to harvest maximum susta<strong>in</strong>able yield (MSY), while the average catchrate dur<strong>in</strong>g this same period was only one-sixth of the rate recorded <strong>in</strong> the 1950s.(Armada, 2004)6

Chapter 2: BACKGROUND & RATIONALE• Overall, fish <strong>in</strong> highly exploited areas <strong>in</strong> the Philipp<strong>in</strong>es are be<strong>in</strong>g harvested at a level30% more than their capacity to reproduce. (ICLARM [WorldFish Center], 2002)• Substantial decl<strong>in</strong>es have been noted <strong>in</strong> the abundance of large, commercially valuablespecies like snappers, sea catfish and Spanish mackerels. (Armada, 2004)MORE HARD FACTSEven now, we are feel<strong>in</strong>g the impacts of a severely dim<strong>in</strong>ished resource. The excessfish<strong>in</strong>g happen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> our country is result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> economic losses conservatively estimated atabout Php6.25 billion per year <strong>in</strong> lost fish catch. The Philipp<strong>in</strong>es, one of the world’s largestfish-produc<strong>in</strong>g nations, is ironically among the top 10 low-<strong>in</strong>come, food-deficit countries ofthe world. Fish still accounts for more than half of the total animal prote<strong>in</strong> consumed <strong>in</strong> thecountry, but per capita national consumption of fish dropped from 40 kg <strong>in</strong> 1987 to 24 kg <strong>in</strong>1996. By some estimates, if no appropriate action is taken to reverse decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g per capitafish production trends, only about 10 kg of fish will be available annually for each Filip<strong>in</strong>oby 2010 (Kurien, 2002; Bernascek, 1996).The decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g trend <strong>in</strong> the small fisher’s catch is not usually clearly evident <strong>in</strong>official reports, which mostly highlight the positive overall growth of the fishery sector.Indeed, production data show that municipal fish land<strong>in</strong>gs are at about the same level asthey were <strong>in</strong> the mid-1970s through the mid-1980s, and appear to be approach<strong>in</strong>g their peak<strong>in</strong> the late 1980s to the early 1990s (Figure 2.1.).The data, however, do not reflect the rapid growth of our fish<strong>in</strong>g population.Accord<strong>in</strong>g to the Philipp<strong>in</strong>e Census on <strong>Fisheries</strong>, there were 584,000 municipal fish<strong>in</strong>goperators on record <strong>in</strong> 1980, and 1.8 million <strong>in</strong> 2002, more than 98% of them <strong>in</strong>dividualoperators. (NSO, 2005) That’s a more than 200% jump <strong>in</strong> the number of small-scale fish<strong>in</strong>goperators <strong>in</strong> just over two decades! And with an average of 5 persons for every fisherhousehold (NSO, 2005), we’re talk<strong>in</strong>g about nearly 10 million Filip<strong>in</strong>os that rely directly onsmall-scale fish<strong>in</strong>g for food, nearly 10 million Filip<strong>in</strong>os that will be displaced by a collapseof our fisheries. GlossaryOn the ground, nearly everywhere you go <strong>in</strong> the Philipp<strong>in</strong>es every other fisher willconfirm the decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> his average daily catch, from two-figure levels just over a decade agoto under 3kg today — and he will also say the quality of his catch used to be better. At afisheries summit <strong>org</strong>anized <strong>in</strong> 2008 by the Department of Agriculture (DA), it was reportedthat marg<strong>in</strong>al fishers <strong>in</strong> the Philipp<strong>in</strong>es were earn<strong>in</strong>g an average <strong>in</strong>come of only Php39 (lessthan USD1) a day! Any further decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> municipal fisheries production will be sure todevastate this large segment of our fish<strong>in</strong>g population.WISDOM IN HINDSIGHTThis, <strong>in</strong> a nutshell, is the problem: The world’s technological capacity to exploit(and unfortunately degrade) the sea has equaled the great human propensity to pursue7

MANAGING MUNICIPAL MARINE CAPTURE FISHERIES IN THE PHILIPPINES: Context, Framework, Concepts and Pr<strong>in</strong>ciplesFigure 2.1. Decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g fish catches. Records (BAS, 2001) of total mar<strong>in</strong>e fishery land<strong>in</strong>gs by bothmunicipal and commercial operations (top diagram) do not quite reflect what scientists say is aseverely degraded resource. But research conducted by the WorldFish Center <strong>in</strong> 1998-2001found that, overall, “the level of fish<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the grossly modified stock (<strong>in</strong> the Philipp<strong>in</strong>es) is 30% higherthan it should be.” (ICLARM [WorldFish Center], 2002) Analyses of catch per unit effort (CPUE) <strong>in</strong>six coastal prov<strong>in</strong>ces <strong>in</strong> the Philipp<strong>in</strong>es for the common hook-and-l<strong>in</strong>e type of fish<strong>in</strong>g reveal evenmore alarm<strong>in</strong>g results: that fish catch is <strong>in</strong> some cases less than 5% of the orig<strong>in</strong>al levels of only a fewdecades ago (bottom diagram). CPUE shows the catch of fish or fishery for a given fish<strong>in</strong>g gear andlevel of effort over time that such fish<strong>in</strong>g gear is applied. (Green et al, 2003)maximum short-term economic ga<strong>in</strong>s, which far exceeds the sea’s capacity to repair andreplenish itself.In his eloquent Unnatural History of the Sea (2007), mar<strong>in</strong>e biologist Callum Robertstraces the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>gs of the <strong>in</strong>tensification of mar<strong>in</strong>e capture fisheries to the 11 th century.Until then, most fish<strong>in</strong>g happened <strong>in</strong>land, but as fish<strong>in</strong>g techniques improved andfreshwater quality deteriorated because of pollution, fishers turned to the sea for food and<strong>in</strong>come.8

Chapter 2: BACKGROUND & RATIONALEInitially, fish<strong>in</strong>g was concentrated <strong>in</strong> coastal waters, partly because nearshorestocks were sufficient to meet (mostly local) demand, and partly because availabletechnology at the time did not allow fishers to travel long distances and still br<strong>in</strong>g theirperishable goods to market. In time, with<strong>in</strong> the limited conf<strong>in</strong>es of the coastal waters, moreefficient fish<strong>in</strong>g technologies were developed, fish<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>tensified, resource use conflictsgrew, and regulations became necessary. (Roberts, 2007)It appears the destructive nature of trawls was recognized early on. Roberts (2007)says the beam trawl was met with hostility when it was <strong>in</strong>troduced <strong>in</strong> the 14 th century. Afew centuries later, France made the practice of trawl<strong>in</strong>g a capital offense, and twofishermen were executed <strong>in</strong> England “for us<strong>in</strong>g metal cha<strong>in</strong>s on their beam trawls (standardissue on the beam trawl today) to help scare fish off the bottom and <strong>in</strong>to the nets.” Still, saysRoberts, trawl<strong>in</strong>g was too lucrative to be totally abandoned and thus never completelydisappeared.A drastic shift <strong>in</strong> policy came dur<strong>in</strong>g the Industrial Revolution <strong>in</strong> the 1800s. Majoradvances <strong>in</strong> sea and land transport and refrigeration dur<strong>in</strong>g this period provided themiss<strong>in</strong>g l<strong>in</strong>k between fisher and market. The new technologies allowed fishers to travelfarther out to sea <strong>in</strong> search of new fish<strong>in</strong>g grounds. More crucially, these technologies gavethem access to a much bigger market. Demand for fish exploded and a new worldviewdom<strong>in</strong>ated. Now that all of the sea was potentially with<strong>in</strong> human reach, fishers – as well aspolicymakers and even some scientists – were conv<strong>in</strong>ced that the productivity of the sea was<strong>in</strong>exhaustible. Despite early evidence of fish stock depletion <strong>in</strong> many areas, many fish<strong>in</strong>gregulations were lifted, trawl<strong>in</strong>g and other efficient gear became the methods of choice, andfisheries expanded with a vengeance. (Roberts, 2007)And so it was until recently <strong>in</strong> the Philipp<strong>in</strong>es. For much of the last century, wepursued coastal and mar<strong>in</strong>e development as if the sea could be exploited without limit,through the use of more efficient gear, <strong>in</strong> an open access regime. Even as we began to seesigns of distress <strong>in</strong> many of our fish<strong>in</strong>g grounds and despite warn<strong>in</strong>gs from a grow<strong>in</strong>gnumber of scientists, we were stuck with the delusion that the problem with our fisherieswas not one of resource decl<strong>in</strong>e, but a problem of access to the resource, which could besolved by technology.Thankfully, <strong>in</strong> recent years, beliefs have changed, no doubt because resourcedegradation and decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g trends <strong>in</strong> fish catch have become too hard to ignore. Clearly,fish<strong>in</strong>g cannot be susta<strong>in</strong>able without regulation and management. Fishers tend to catchtheir prey way too much like any typical human hunter does. Hunters are opportunistic –they actively seek their prey, adjust to its environment, and adapt their activity to maximizethe opportunities. In the view of paleontologist Niles Eldrige, “no natural <strong>in</strong>st<strong>in</strong>ct urges thehuman hunter to practice susta<strong>in</strong>ability; hunters are by nature opportunists with a tendencyto kill whatever they can get.” (Radkau, 2008)It is our responsibility as fisheries managers to help ensure the susta<strong>in</strong>ability ofwhat is essentially the last commercially hunted species <strong>in</strong> the world. If we do not do our job9

MANAGING MUNICIPAL MARINE CAPTURE FISHERIES IN THE PHILIPPINES: Context, Framework, Concepts and Pr<strong>in</strong>cipleswell, fish would surely go down the path of all commercially hunted species before it –toward depletion of disastrous proportions, if not ext<strong>in</strong>ction. (Myers and Worm, 2003;Weber, 1993)Roberts told the Wash<strong>in</strong>gton Post (2007) <strong>in</strong> an <strong>in</strong>terview, “Many of the problems wesee <strong>in</strong> the oceans today were recognized 100 years ago, as were many of the solutions. Thedifference is that there was so much more <strong>in</strong> the sea then, and people felt they didn’t need toact, but could just fish somewhere else or for someth<strong>in</strong>g else. We no longer have that choice.Today, we must act to br<strong>in</strong>g depleted species back, because we have nearly run out ofalternatives (unless you like jellyfish).”The job of a fisheries manager is perhaps a bigger challenge now than it has everbeen because of the severity of our fisheries problem. But as a fisheries manager who mustnecessarily advocate conservation and timely management <strong>in</strong>tervention, you will no longerfeel like a lone voice <strong>in</strong> the wilderness, because you have all of history to back you up, atleast on these several key po<strong>in</strong>ts:• The sea is neither <strong>in</strong>exhaustible nor <strong>in</strong>destructible.• Unless properly managed and regulated, fish<strong>in</strong>g easily escalates <strong>in</strong>to overfish<strong>in</strong>g.• Our fisheries problem is real and grow<strong>in</strong>g; as it grows, our options shr<strong>in</strong>k.• Solutions are available, but time is runn<strong>in</strong>g short.FACTS OF (FISH) LIFEWe’ve seen how fish<strong>in</strong>g has been allowed to expand so much as to deplete our fishstocks; now we will take a closer look at the world of sea fishes, how it works, and how itmay react to various stresses, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g fish<strong>in</strong>g. As much as we must learn from whatRoberts (2007) calls the “unnatural history of the sea,” we also need to understand thenatural history of fish and its environment.Learn<strong>in</strong>g especially the ecological <strong>in</strong>teractions and relationships that characterizeocean life will help us understand better the concepts and pr<strong>in</strong>ciples of fisheriesmanagement, which <strong>in</strong> turn will enable us to th<strong>in</strong>k both critically and creatively as we dealwith our fishery problems and determ<strong>in</strong>e our actions.But first, here are some unavoidable fish facts that should be our mantra <strong>in</strong> fisheriesmanagement (based mostly on Cunn<strong>in</strong>gham and Saigo, 1997):• Fish are a biological resource with biological limits.• Fish have limits to the environmental conditions they can endure.• Like any biological population, a fish population cannot survive below a m<strong>in</strong>imumsize.• No population exists <strong>in</strong> complete isolation; all of nature is <strong>in</strong>terconnected.• Every species plays a role <strong>in</strong> its community, called its ecological niche.These are the givens of fish life; as fisheries managers, there is really not much wecan do to directly manage them. But with some basic understand<strong>in</strong>g of fish life <strong>in</strong> particular10

Chapter 2: BACKGROUND & RATIONALEand ocean life <strong>in</strong> general, we can do a better job of identify<strong>in</strong>g and manag<strong>in</strong>g those th<strong>in</strong>gsthat we can actually control – above all, fish<strong>in</strong>g and the other human activities that impactthe susta<strong>in</strong>ability of our fishery resources. GlossaryThe follow<strong>in</strong>g sections conta<strong>in</strong> more detailed discussions of fish ecology and otherimportant concepts to help guide us as we beg<strong>in</strong> to tackle the many practical challenges offisheries management. But first, let’s get some def<strong>in</strong>itions straight:• Population – a group of <strong>in</strong>dividuals of the same species <strong>in</strong>habit<strong>in</strong>g a certa<strong>in</strong> area.• Species – a group of similar <strong>org</strong>anisms that can reproduce sexually amongthemselves.• Community – consists of populations of various liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>org</strong>anisms liv<strong>in</strong>g and<strong>in</strong>teract<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a certa<strong>in</strong> area at a given time.• Fish stock – the total mass of a fishery resource, which is usually identified by itslocation and may consist of one or several species.WATER MATTERSFish can live <strong>in</strong> almost any place where there is water. It is known to exist at analtitude of 4,572 meters above the sea level, <strong>in</strong> a lake <strong>in</strong> the Andes Mounta<strong>in</strong> Range <strong>in</strong> SouthAmerica called Titicaca. It is also known to survive <strong>in</strong> the deepest part of the MarianasTrench, at 11,033 meters. We can with certa<strong>in</strong>ty therefore conclude that the total verticalrange of fish occurrence is 15,605 meters. That’s a distance of over 15 kilometers, anextensive range that, along with the fact that water covers nearly three-quarters of the earth’ssurface, gives an <strong>in</strong>dication of the ability of fish to adapt to various aquatic environments. GlossaryWater on earth is distributed among <strong>in</strong>teract<strong>in</strong>g compartments where it resides forshort or long periods of time (<strong>in</strong> the deepest oceans, up to tens of thousands of years).Nearly 98% of all liquid water <strong>in</strong> the world is <strong>in</strong> the oceans, circulated and exchangedthrough evaporation, ra<strong>in</strong>fall, riverdischarge, groundwater flow andrunoff among the differentcompartments <strong>in</strong> a process calledhydrologic (water) cycle. (Figure 2.2)The hydrologic cycleperforms three vital functions: 1) Itsupplies fresh water to the landmasses; 2) It regulates worldtemperatures; and 3) It makes ourclimate fit to be lived <strong>in</strong>. The water<strong>in</strong> our oceans is too salty for mosthuman uses, but by its sheer volume,it is our planet’s ma<strong>in</strong> temperaturemoderator and climate regulator.(Cunn<strong>in</strong>gham and Saigo, 1997)Figure 2.2. The water cycle. Driven by solar energy and gravity, thehydrologic cycle moves water between the earth’s aquatic, atmosphericand terrestrial compartments. (image adapted from Met Office)11

MANAGING MUNICIPAL MARINE CAPTURE FISHERIES IN THE PHILIPPINES: Context, Framework, Concepts and Pr<strong>in</strong>ciplesTHE OCEANS IN DEPTH GlossaryThe oceans actually form a s<strong>in</strong>gle unbroken reservoir, but they do not have the sameproperties. The presence of shallow and narrow parts between them reduces waterexchange, which results <strong>in</strong> variations <strong>in</strong> composition, climatic effects and surface elevations.Different water densities, different sal<strong>in</strong>ities and different temperatures further <strong>in</strong>hibit themix<strong>in</strong>g of water, form<strong>in</strong>g sharp boundaries or ocean layers. Such physical and chemicalvariations <strong>in</strong>fluence the k<strong>in</strong>ds of plant and animal life that occur <strong>in</strong> the different oceans andocean layers.For purposes of research and study, scientists have devised several ways to classifythe oceans <strong>in</strong>to different regions based on the physical and biological conditions of theseareas. One classification uses the edge of the cont<strong>in</strong>ental shelf – that is, the underwaterextension of the marg<strong>in</strong>s of the landmass – as the po<strong>in</strong>t of del<strong>in</strong>eation between two regions(Figure 2.3):1. the neritic prov<strong>in</strong>ce, which <strong>in</strong>cludes the water column overly<strong>in</strong>g the cont<strong>in</strong>entalshelf, more or less most or all the coastal zone, and2. the oceanic prov<strong>in</strong>ce, which encompasses the rest of the open waters up to thedeepest portion of the ocean.One major difference between these two prov<strong>in</strong>ces lies <strong>in</strong> the fact that the neriticprov<strong>in</strong>ce is contiguous to the landmass and therefore directly <strong>in</strong>fluenced by it. There arebodies of water whose entire extent lies over the cont<strong>in</strong>ental shelves and entirely with<strong>in</strong> theneritic prov<strong>in</strong>ce. GlossaryAnother classification divides the ocean <strong>in</strong>to two broad categories called realms(Figure 2.3):1. The benthic realm, which extends from the high tide l<strong>in</strong>e on the shore to thedeepest parts of the seafloor, and2. The pelagic realm, which consists of ocean waters, the “water column”.The two realms are further divided <strong>in</strong>to separate zones or layers (Figure 2.3).IN THE WATER GlossaryThe subdivision of the two realms is based primarily on the liv<strong>in</strong>g conditions <strong>in</strong> thedifferent zones. One common classification divides the pelagic realm <strong>in</strong>to two layersaccord<strong>in</strong>g to sunlight penetration (Figure 2.3):1. The light zone is the layer of water that can be reached by sunlight, limited to thedepth of light penetration, which varies depend<strong>in</strong>g upon the <strong>in</strong>tensity of sunlightand the transparency of the water. Generally, the depth of light penetration rangesbetween 100 and 200 meters.2. The dark zone is the water column below the light zone, where there is a permanentabsence of light.12

Chapter 2: BACKGROUND & RATIONALEFigure 2.3. Ocean zones. Scientists have classified the sea <strong>in</strong>to realms, zones and divisions, such as those shown above, because ofdifferences <strong>in</strong> the liv<strong>in</strong>g conditions <strong>in</strong> different parts of the water and the seabed. (Image adapted from FAO, 2005; Wikipedia.<strong>org</strong>, Ocean).The light zone serves as the <strong>in</strong>terface between the atmosphere and the water mass,allow<strong>in</strong>g exchange of energy between them. As such, it is <strong>in</strong>fluenced by the natural cycle oflight (the so-called light-dark cycle), as well as climatic and seasonal changes <strong>in</strong> theatmosphere.Obviously, the ma<strong>in</strong> difference between the light and dark zones is the presence orabsence of light. The deep dark ocean layers are also characterized by extremely highpressure (due to the weight of the water above) and relatively low temperature with smallfluctuations.ON THE SEAFLOOR GlossaryIn the benthic realm, our primary <strong>in</strong>terest would be that part of the seafloor calledthe littoral zone. This zone is reckoned at 0 to 200 meters from the highest tide level, wellwith<strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>fluence of sunlight. It is where we f<strong>in</strong>d many of the mar<strong>in</strong>e habitats we are most13

MANAGING MUNICIPAL MARINE CAPTURE FISHERIES IN THE PHILIPPINES: Context, Framework, Concepts and Pr<strong>in</strong>ciplesfamiliar with – the rocky shorel<strong>in</strong>es, sandy beaches, mangroves, seagrass beds and coralreefs.The littoral zone is subdivided <strong>in</strong>to three zones based on exposure to seawater(Figure 2.3):1. Spray or splash zone (also called supralittoral zone);2. Intertidal zone (also, mesolittoral zone); and3. Sublittoral zone. GlossaryThe spray zone is the meet<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>t between land and ocean life, above the meanhighest water l<strong>in</strong>e, so named because it gets seawater mostly <strong>in</strong> the form of ocean spray,splash or mist. It is covered by water only dur<strong>in</strong>g extremely high tides or <strong>in</strong> the presence ofstrong waves, usually dur<strong>in</strong>g storms or high w<strong>in</strong>ds. The long <strong>in</strong>tervals between such mar<strong>in</strong>e<strong>in</strong>fluences allow atmospheric and terrestrial <strong>in</strong>fluences to dom<strong>in</strong>ate. Sunlight affects thiszone directly, result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> rapid changes <strong>in</strong> temperature, as well as extreme variations <strong>in</strong>sal<strong>in</strong>ity. Tidal pools may form after a storm that can have freshwater conditions after aheavy ra<strong>in</strong>, becom<strong>in</strong>g concentrated saltwater after several sunny days, eventually dry<strong>in</strong>g upafter a prolonged drought period, and then form<strong>in</strong>g aga<strong>in</strong> under suitable conditions. GlossaryThe <strong>in</strong>tertidal zone, regarded as the “real” littoral zone, extends from the meanhighest water level to the mean lowest water level. Organisms <strong>in</strong> this zone are subject toalternat<strong>in</strong>g floods and droughts twice each day, follow<strong>in</strong>g the six-and-a-half-hour tidalrhythm. It is considered a very hostile and complicated habitat because of the ever-chang<strong>in</strong>gtide tim<strong>in</strong>g and height, <strong>in</strong> addition to the fact that this is where climate changes and humanactivities make their greatest impact.The environment <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>tertidal zone is one of harsh extremes. The tide br<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong>water like clockwork, but sal<strong>in</strong>ity is highly variable, rang<strong>in</strong>g from nearly fresh with ra<strong>in</strong>, tohighly sal<strong>in</strong>e and dry salt between tidal <strong>in</strong>undations. The mechanical forces of wave actioncan knock <strong>in</strong>tertidal residents loose. And temperatures can vary greatly from very highunder the full sun to very low <strong>in</strong> cold weather.The <strong>in</strong>tertidal zone is generally divided <strong>in</strong>to three layers based on the length of timeit is submerged <strong>in</strong> water. The uppermost layer is covered by water only dur<strong>in</strong>g the highest tideso it experiences dry periods daily, the middle layer is submerged at high tide and exposed atlow tide, and the lowest layer is exposed only dur<strong>in</strong>g the lowest tide. GlossaryBelow the <strong>in</strong>tertidal zone is the sublittoral zone, which extends from the meanlowest water level to the deepest po<strong>in</strong>t where benthic plants are still found, at the farthestdepth of sunlight penetration. This zone is permanently covered with water.14