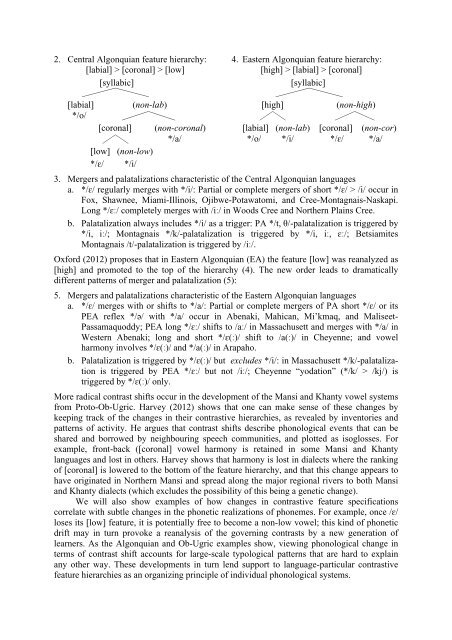

2. Central Algonquian feature hierarchy: 4. Eastern Algonquian feature hierarchy:[labial] > [coronal] > [low][high] > [labial] > [coronal][syllabic][syllabic]wowo[labial] (non-lab) [high] (non-high)*/o/ ei ty ru[coronal] (non-coronal) [labial] (non-lab) [coronal] (non-cor)ty */a/ */o/ */i/ */ɛ/ */a/[low] (non-low)*/ɛ/ */i/3. Mergers and palatalizations characteristic of <strong>the</strong> Central Algonquian languagesa. */ɛ/ regularly merges with */i/: Partial or complete mergers of short */ɛ/ > /i/ occur <strong>in</strong>Fox, Shawnee, Miami-Ill<strong>in</strong>ois, Ojibwe-Potawatomi, and Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi.Long */ɛː/ completely merges with /iː/ <strong>in</strong> Woods Cree and Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Pla<strong>in</strong>s Cree.b. Palatalization always <strong>in</strong>cludes */i/ as a trigger: PA */t, θ/-palatalization is triggered by*/i, iː/; Montagnais */k/-palatalization is triggered by */i, iː, ɛː/; BetsiamitesMontagnais /t/-palatalization is triggered by /iː/.Oxford (2012) proposes that <strong>in</strong> Eastern Algonquian (EA) <strong>the</strong> feature [low] was reanalyzed as[high] and promoted to <strong>the</strong> top of <strong>the</strong> hierarchy (4). The new order leads to dramaticallydifferent patterns of merger and palatalization (5):5. Mergers and palatalizations characteristic of <strong>the</strong> Eastern Algonquian languagesa. */ɛ/ merges with or shifts to */a/: Partial or complete mergers of PA short */ɛ/ or itsPEA reflex */əә/ with */a/ occur <strong>in</strong> Abenaki, Mahican, Mi’kmaq, and Maliseet-Passamaquoddy; PEA long */ɛː/ shifts to /aː/ <strong>in</strong> Massachusett and merges with */a/ <strong>in</strong>Western Abenaki; long and short */ɛ(ː)/ shift to /a(ː)/ <strong>in</strong> Cheyenne; and vowelharmony <strong>in</strong>volves */ɛ(ː)/ and */a(ː)/ <strong>in</strong> Arapaho.b. Palatalization is triggered by */ɛ(ː)/ but excludes */i/: <strong>in</strong> Massachusett */k/-palatalizationis triggered by PEA */ɛː/ but not /iː/; Cheyenne “yodation” (*/k/ > /kj/) istriggered by */ɛ(ː)/ only.More radical contrast shifts occur <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> development of <strong>the</strong> Mansi and Khanty vowel systemsfrom Proto-Ob-Ugric. Harvey (2012) shows that one can make sense of <strong>the</strong>se changes bykeep<strong>in</strong>g track of <strong>the</strong> changes <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir contrastive hierarchies, as revealed by <strong>in</strong>ventories andpatterns of activity. He argues that contrast shifts describe phonological events that can beshared and borrowed by neighbour<strong>in</strong>g speech communities, and plotted as isoglosses. Forexample, front-back ([coronal] vowel harmony is reta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> some Mansi and Khantylanguages and lost <strong>in</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs. Harvey shows that harmony is lost <strong>in</strong> dialects where <strong>the</strong> rank<strong>in</strong>gof [coronal] is lowered to <strong>the</strong> bottom of <strong>the</strong> feature hierarchy, and that this change appears tohave orig<strong>in</strong>ated <strong>in</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Mansi and spread along <strong>the</strong> major regional rivers to both Mansiand Khanty dialects (which excludes <strong>the</strong> possibility of this be<strong>in</strong>g a genetic change).We will also show examples of how changes <strong>in</strong> contrastive feature specificationscorrelate with subtle changes <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> phonetic realizations of phonemes. For example, once /ɛ/loses its [low] feature, it is potentially free to become a non-low vowel; this k<strong>in</strong>d of phoneticdrift may <strong>in</strong> turn provoke a reanalysis of <strong>the</strong> govern<strong>in</strong>g contrasts by a new generation oflearners. As <strong>the</strong> Algonquian and Ob-Ugric examples show, view<strong>in</strong>g phonological change <strong>in</strong>terms of contrast shift accounts for large-scale typological patterns that are hard to expla<strong>in</strong>any o<strong>the</strong>r way. These developments <strong>in</strong> turn lend support to language-particular contrastivefeature hierarchies as an organiz<strong>in</strong>g pr<strong>in</strong>ciple of <strong>in</strong>dividual phonological systems.

Pro-drop as ellipsis: evidence from <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terpretation of null argumentsMaia Dugu<strong>in</strong>eUniversity of <strong>the</strong> Basque Country UPV/EHU & University of NantesGOAL. In this talk, I defend a DP/NP-ellipsis (DPE) analysis of pro-drop cross-l<strong>in</strong>guistically.1 PRO-DROP AS DPE. The standard view is that <strong>the</strong>re are different types of pro-dropphenomena across languages (cf. recently Holmberg 2010); e.g. DPE is at play <strong>in</strong> Japaneselikelanguages (cf. Kim 1999, Saito 2007, Takahashi 2008), while agreement is whatlicenses/identifies null arguments <strong>in</strong> Spanish-like languages (cf. Rizzi 1986, Barbosa 1995,2009).1.1 Occam's razor. Unless proven wrong, a unified <strong>the</strong>ory of pro-drop should be favored overone that appeals to different accounts for different languages. While it is difficult to reducepro-drop <strong>in</strong> agreement-less languages like Japanese to an agreement-related phenomenon,reduc<strong>in</strong>g pro-drop <strong>in</strong> Spanish-like languages to ellipsis makes sense, <strong>in</strong> particular given thatellipsis is <strong>in</strong>dependently attested <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> grammar and universally available <strong>in</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciple.1.2 Evidence. The ma<strong>in</strong> argument <strong>in</strong> favor of not reduc<strong>in</strong>g pro-drop <strong>in</strong> Spanish-like languagesto DPE is that, as assumed s<strong>in</strong>ce Oku (1998), unlike <strong>in</strong> e.g. Japanese (1), <strong>in</strong> Spanish (2) nullsubjects cannot be <strong>in</strong>terpreted as lexical DPs (i.e. <strong>the</strong>y do not allow a sloppy read<strong>in</strong>g (SR)) (cf.also Saito 2007, Takahashi 2007). Contradict<strong>in</strong>g this generalization, I present novel data fromSpanish, where null subjects allow SR (3), show<strong>in</strong>g that a DPE analysis is <strong>in</strong>deed possible forthis type of language (SR is not available with an overt subject).(1) A. Mary-wa [zibun-no teian-ga saiyo-sare-ru-to] omotteiru. JapaneseMary-TOP self-GEN proposal-NOM accept-PASS-PRS-that th<strong>in</strong>k (Oku 1998: 165)'Lit. Mary th<strong>in</strong>ks that self’s proposal will be accepted.'B. John-mo [[e] saiyo-sare-ru-to] omotteiru.John-also accept-PASS-PRS-that th<strong>in</strong>k'Lit. John also th<strong>in</strong>ks that {it(i.e. her proposal)/his proposal}will be accepted.'(2) A: María cree que [su propuesta será aceptada]. SpanishMaria believes that her proposal will.be accepted (Oku 1998: 165)B: Juan también cree que [[e]será aceptada].Juan also believes that will.be accepted'Juan also believes that {it (i.e. her proposal)/*his proposal} will be accepted.'(3) A: El primer año de tesis, mi director me trató muy bien.<strong>the</strong> first year of <strong>the</strong>sis my director cl.1sg(DAT) treat very well.B: Pues, ¡a mi [e] no me hizo caso!well to me NEG cl.1sg(DAT) made attentionLit. 'Well, to me, {he (i.e. your director)/my director} didn't pay attention!'1.3 Account<strong>in</strong>g for <strong>the</strong> 'exception'. I argue that (2) can be accounted for <strong>in</strong>dependently, <strong>in</strong>terms of b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g. The SR results from <strong>the</strong> elided constituent conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g a bound variablepronoun (BV) (as opposed to a referential one) (Lasnik 1976, Re<strong>in</strong>hart 1983, Fox 2000).Assum<strong>in</strong>g that b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g relations reduce to local Agree operations (Reuland 2005, 2011,Gallego 2010), I argue that <strong>the</strong> contrast <strong>in</strong> (2)-(3) is expla<strong>in</strong>ed as follows: (i) a BV is onlypossible <strong>in</strong> constructions <strong>in</strong> which it can Agree locally (with <strong>the</strong> object clitic <strong>in</strong> (3)); (ii) <strong>in</strong>cases like (2) it cannot Agree locally, and thus <strong>the</strong> pronoun can only be referential(coreferential with, but not bound by, <strong>the</strong> antecedent), as a result of which <strong>the</strong> SR is notavailable. Regard<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> availability of <strong>the</strong> SR <strong>in</strong> (1), I argue that it cannot be accounted forby <strong>the</strong> absence of agreement morphology, s<strong>in</strong>ce many languages without subject-agreementdo not allow SRs <strong>in</strong> contexts like (1) (Ch<strong>in</strong>ese (Takahashi 2007), Malayalam (Takahashi2012), and Colloquial S<strong>in</strong>gapore English (Sato 2012)). Conclud<strong>in</strong>g from this that <strong>the</strong>

- Page 1 and 2:

GLOW Newsletter #70, Spring 2013Edi

- Page 3 and 4:

INTRODUCTIONWelcome to the 70 th GL

- Page 5:

Welcome to GLOW 36, Lund!The 36th G

- Page 8 and 9:

REIMBURSEMENT AND WAIVERSThe regist

- Page 10 and 11:

STATISTICS BY COUNTRYCountry Author

- Page 12 and 13:

15:45-16:00 Coffee break16:00-17:00

- Page 14 and 15:

14:00-15:00 Adam Albright (MIT) and

- Page 16 and 17:

17:00-17:30 Anna Maria Di Sciullo (

- Page 18 and 19:

16.10-16.50 Peter Svenonius (Univer

- Page 20 and 21:

GLOW 36 WORKSHOP PROGRAM IV:Acquisi

- Page 22 and 23: The impossible chaos: When the mind

- Page 24 and 25: 17. Friederici, A. D., Trends Cogn.

- Page 26 and 27: Second, tests replicated from Bruen

- Page 28 and 29: clusters is reported to be preferre

- Page 30 and 31: occur (cf. figure 1). Similar perfo

- Page 32 and 33: argument that raises to pre-verbal

- Page 34 and 35: Timothy Bazalgette University of

- Page 36 and 37: . I hurt not this knee now (Emma 2;

- Page 38 and 39: Rajesh Bhatt & Stefan Keine(Univers

- Page 40 and 41: SIZE MATTERS: ON DIACHRONIC STABILI

- Page 42 and 43: ON THE ‘MAFIOSO EFFECT’ IN GRAM

- Page 44 and 45: The absence of coreferential subjec

- Page 46 and 47: PROSPECTS FOR A COMPARATIVE BIOLING

- Page 48 and 49: A multi-step algorithm for serial o

- Page 50 and 51: Velar/coronal asymmetry in phonemic

- Page 52 and 53: On the bilingual acquisition of Ita

- Page 54 and 55: Hierarchy and Recursion in the Brai

- Page 56 and 57: Colorful spleeny ideas speak furiou

- Page 58 and 59: A neoparametric approach to variati

- Page 60 and 61: Lexical items merged in functional

- Page 62 and 63: Setting the elements of syntactic v

- Page 64 and 65: Language Faculty, Complexity Reduct

- Page 66 and 67: Don’t scope your universal quanti

- Page 68 and 69: Restricting language change through

- Page 70 and 71: 4. Conclusion This micro-comparativ

- Page 74 and 75: availability of the SR reading in (

- Page 76 and 77: Repairing Final-Over-Final Constrai

- Page 78 and 79: a PF interface phenomenon as propos

- Page 80 and 81: (b) Once the learner has determined

- Page 82 and 83: cognitive recursion (including Merg

- Page 84 and 85: can be null, or lexically realized,

- Page 86 and 87: feature on C and applies after Agre

- Page 88 and 89: Nobu Goto (Mie University)Deletion

- Page 90 and 91: Structural Asymmetries - The View f

- Page 92 and 93: FROM INFANT POINTING TO THE PHASE:

- Page 94 and 95: Some Maladaptive Traits of Natural

- Page 96 and 97: Constraints on Concept FormationDan

- Page 98 and 99: More on strategies of relativizatio

- Page 100 and 101: ReferencesBayer, J. 1984. COMP in B

- Page 102 and 103: Improper movement and improper agre

- Page 104 and 105: Importantly, while there are plausi

- Page 106 and 107: This hypothesis makes two predictio

- Page 108 and 109: (3) a. Það finnst alltaf þremur

- Page 110 and 111: (2) Watashi-wa hudan hougaku -wa /*

- Page 112 and 113: However when the VP (or IP) is elid

- Page 114 and 115: More specifically, this work reflec

- Page 116 and 117: modality, or ii) see phonology as m

- Page 118 and 119: (I) FWHA The wh-word shenme ‘what

- Page 120 and 121: 1The historical reality of biolingu

- Page 122 and 123:

Rita Manzini, FirenzeVariation and

- Page 124 and 125:

Non-counterfactual past subjunctive

- Page 126 and 127:

THE GRAMMAR OF THE ESSENTIAL INDEXI

- Page 128 and 129:

Motivating head movement: The case

- Page 130 and 131:

Limits on Noun-suppletionBeata Mosk

- Page 132 and 133:

Unbounded Successive-Cyclic Rightwa

- Page 134 and 135:

Same, different, other, and the his

- Page 136 and 137:

Selectivity in L3 transfer: effects

- Page 138 and 139:

Anaphoric dependencies in real time

- Page 140 and 141:

Constraining Local Dislocation dial

- Page 142 and 143:

A Dual-Source Analysis of GappingDa

- Page 144 and 145:

[9] S. Repp. ¬ (A& B). Gapping, ne

- Page 146 and 147:

of Paths into P path and P place is

- Page 148 and 149:

Deriving the Functional HierarchyGi

- Page 150 and 151:

Reflexivity without reflexivesEric

- Page 152 and 153:

Reuland, E. (2001). Primitives of b

- Page 154 and 155:

on v, one associated with uϕ and t

- Page 156 and 157:

Merge when applied to the SM interf

- Page 158 and 159:

1 SachsThe Semantics of Hindi Multi

- Page 160 and 161:

Covert without overt: QR for moveme

- Page 162 and 163:

Morpho-syntactic transfer in L3 acq

- Page 164 and 165:

one where goals receive a theta-rel

- Page 166 and 167:

51525354555657585960616263646566676

- Page 168 and 169:

follow Harris in assuming a ranked

- Page 170 and 171:

changing instances of nodes 7 and 8

- Page 172 and 173:

Sam Steddy, steddy@mit.eduMore irre

- Page 174 and 175:

Fleshing out this model further, I

- Page 176 and 177:

(5) Raman i [ CP taan {i,∗j}Raman

- Page 178 and 179:

properties with Appl (introduces an

- Page 180 and 181:

econstruct to position A then we ca

- Page 182 and 183:

(5) Kutik=i ez guret-a.dog=OBL.M 1S

- Page 184 and 185:

sults summarized in (2) suggest tha

- Page 186 and 187:

Building on Bhatt’s (2005) analys

- Page 188 and 189:

Underlying (derived from ON) /pp, t

- Page 190 and 191:

out, as shown in (3) (that the DP i

- Page 192 and 193:

Word order and definiteness in the

- Page 194 and 195:

Visser’s Generalization and the c

- Page 196 and 197:

the key factors. The combination of

- Page 198 and 199:

Parasitic Gaps Licensed by Elided S

- Page 200 and 201:

Stages of grammaticalization of the