Practical Information - Generative Linguistics in the Old World

Practical Information - Generative Linguistics in the Old World

Practical Information - Generative Linguistics in the Old World

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

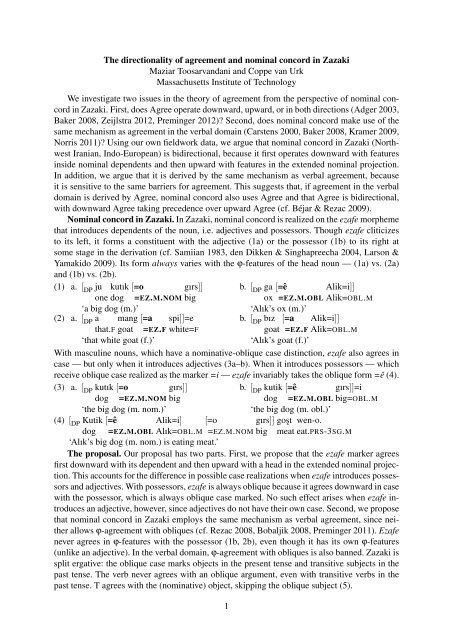

The directionality of agreement and nom<strong>in</strong>al concord <strong>in</strong> ZazakiMaziar Toosarvandani and Coppe van UrkMassachusetts Institute of TechnologyWe <strong>in</strong>vestigate two issues <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ory of agreement from <strong>the</strong> perspective of nom<strong>in</strong>al concord<strong>in</strong> Zazaki. First, does Agree operate downward, upward, or <strong>in</strong> both directions (Adger 2003,Baker 2008, Zeijlstra 2012, Prem<strong>in</strong>ger 2012)? Second, does nom<strong>in</strong>al concord make use of <strong>the</strong>same mechanism as agreement <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> verbal doma<strong>in</strong> (Carstens 2000, Baker 2008, Kramer 2009,Norris 2011)? Us<strong>in</strong>g our own fieldwork data, we argue that nom<strong>in</strong>al concord <strong>in</strong> Zazaki (NorthwestIranian, Indo-European) is bidirectional, because it first operates downward with features<strong>in</strong>side nom<strong>in</strong>al dependents and <strong>the</strong>n upward with features <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> extended nom<strong>in</strong>al projection.In addition, we argue that it is derived by <strong>the</strong> same mechanism as verbal agreement, becauseit is sensitive to <strong>the</strong> same barriers for agreement. This suggests that, if agreement <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> verbaldoma<strong>in</strong> is derived by Agree, nom<strong>in</strong>al concord also uses Agree and that Agree is bidirectional,with downward Agree tak<strong>in</strong>g precedence over upward Agree (cf. Béjar & Rezac 2009).Nom<strong>in</strong>al concord <strong>in</strong> Zazaki. In Zazaki, nom<strong>in</strong>al concord is realized on <strong>the</strong> ezafe morphemethat <strong>in</strong>troduces dependents of <strong>the</strong> noun, i.e. adjectives and possessors. Though ezafe cliticizesto its left, it forms a constituent with <strong>the</strong> adjective (1a) or <strong>the</strong> possessor (1b) to its right atsome stage <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> derivation (cf. Samiian 1983, den Dikken & S<strong>in</strong>ghapreecha 2004, Larson &Yamakido 2009). Its form always varies with <strong>the</strong> ϕ-features of <strong>the</strong> head noun — (1a) vs. (2a)and (1b) vs. (2b).(1) a. [ DP ju kutık [=oone dog‘a big dog (m.)’(2) a. [ DP a mang [=athat.F goat‘that white goat (f.)’=EZ.M.NOM=EZ.Fgırs]]bigspi]]=ewhite=Fb. [ DP ga [=êox‘Alık’s ox (m.)’b. [ DP bız [=agoat =EZ.F‘Alık’s goat (f.)’=EZ.M.OBLAlik=i]]Alik=OBL.MAlik=i]]Alik=OBL.MWith mascul<strong>in</strong>e nouns, which have a nom<strong>in</strong>ative-oblique case dist<strong>in</strong>ction, ezafe also agrees <strong>in</strong>case — but only when it <strong>in</strong>troduces adjectives (3a–b). When it <strong>in</strong>troduces possessors — whichreceive oblique case realized as <strong>the</strong> marker =i — ezafe <strong>in</strong>variably takes <strong>the</strong> oblique form =ê (4).(3) a. [ DP kutık [=o gırs]]b. [ DP kutik [=ê gırs]]=idog =EZ.M.NOM bigdog =EZ.M.OBL big=OBL.M‘<strong>the</strong> big dog (m. nom.)’‘<strong>the</strong> big dog (m. obl.)’(4) [ DP Kutik [=ê Alik=i] [=o gırs]] goşt wen-o.dog =EZ.M.OBL Alık=OBL.M =EZ.M.NOM big meat eat.PRS-3SG.M‘Alık’s big dog (m. nom.) is eat<strong>in</strong>g meat.’The proposal. Our proposal has two parts. First, we propose that <strong>the</strong> ezafe marker agreesfirst downward with its dependent and <strong>the</strong>n upward with a head <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> extended nom<strong>in</strong>al projection.This accounts for <strong>the</strong> difference <strong>in</strong> possible case realizations when ezafe <strong>in</strong>troduces possessorsand adjectives. With possessors, ezafe is always oblique because it agrees downward <strong>in</strong> casewith <strong>the</strong> possessor, which is always oblique case marked. No such effect arises when ezafe <strong>in</strong>troducesan adjective, however, s<strong>in</strong>ce adjectives do not have <strong>the</strong>ir own case. Second, we proposethat nom<strong>in</strong>al concord <strong>in</strong> Zazaki employs <strong>the</strong> same mechanism as verbal agreement, s<strong>in</strong>ce nei<strong>the</strong>rallows ϕ-agreement with obliques (cf. Rezac 2008, Bobaljik 2008, Prem<strong>in</strong>ger 2011). Ezafenever agrees <strong>in</strong> ϕ-features with <strong>the</strong> possessor (1b, 2b), even though it has its own ϕ-features(unlike an adjective). In <strong>the</strong> verbal doma<strong>in</strong>, ϕ-agreement with obliques is also banned. Zazaki issplit ergative: <strong>the</strong> oblique case marks objects <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> present tense and transitive subjects <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>past tense. The verb never agrees with an oblique argument, even with transitive verbs <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>past tense. T agrees with <strong>the</strong> (nom<strong>in</strong>ative) object, skipp<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> oblique subject (5).1