BirdScope 11 Autumn 25(4)-For Annetta(2).pdf - All About Birds

BirdScope 11 Autumn 25(4)-For Annetta(2).pdf - All About Birds

BirdScope 11 Autumn 25(4)-For Annetta(2).pdf - All About Birds

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

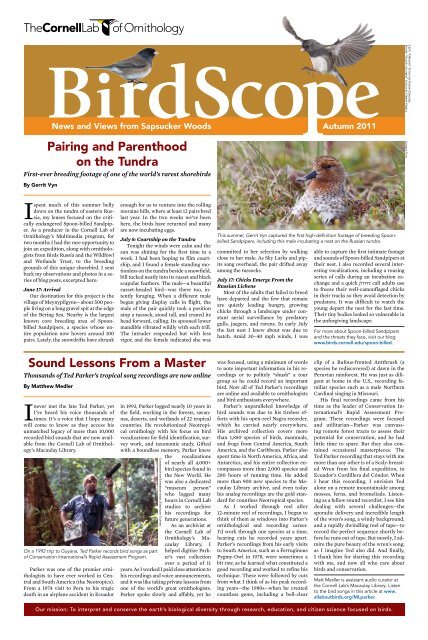

<strong>BirdScope</strong> Vol. <strong>25</strong> (4) <strong>Autumn</strong> 20<strong>11</strong> 3Focus on studentsFiery FoesAn island’s gulls face downtiny attackersBy Luke DeFisherJust two days after final exams endedin May, I was on a boat headedto Appledore Island, Maine. Startingin mid May, I’d be on that tiny, rockyisland for two months, along with fiveother interns in the Research Internshipin Field Science (RIFS) program atCornell’s Shoals Marine Lab. Gulls weredive-bombing my head, but I had ants onmy mind.Students on Appledore study everythingfrom microbes to seals, but I wasinterested in an uninvited guest, the Europeanfire ant. These ants have beenon Appledore since the 1970s, and theysometimes attack Herring Gull nests,swarming over the chicks and stingingthem. As a budding marine ecologist,I wondered if these individual attackscould take a toll on Appledore’s gull populationas a whole.It wouldn’t be the first time an ant affecteda bird species. The closely relatedred fire ant has hurt Northern Bobwhitepopulations in southeastern Texas, andthe big-headed ant threatens WedgetailedShearwaters in Hawaii. Europeanred ants arrived in New England in 1908,and have been an expensive and growingproblem for New England homeownersever since.I marked out 78 Herring Gull nestsand spent the summer recording thechicks’ daily growth and survival for along-term project run by my adviser, DavidBonter, assistant director of CitizenScience at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.With two to three chicks to a nest,I had a lot to monitor. I paid extra attentionto 43 of those nests and saw ant attacksat 17 of them. Adult Herring Gullspreened and shook their feathers asthe ants crawled over them. <strong>For</strong> youngchicks the threat was greater, as scoresof shiny, rust-colored ants covered thechicks’ eyes and tiny bills. Amazinglycamouflaged from larger predators, thechicks’ gray-speckled feathers did littleto hide them from six-legged invaders.Most of the chicks survived ant attacks,but four nests—about nine percentof my sample—lost at least one chick.Keep in mind that the 43 nests I studiedwere only a fraction of the HerringGull nests on Appledore that summer.Ants aren’t exactly driving Herring Gullsoff the island—at least 600 pairs nest onAppledore. Still, I’d like to explore themagnitude of this ant-sized problem abit further.On top of fieldwork, I had to adjust toliving on an island for eight weeks. Withonly one well, I became much moreaware of my water and power use. Believeme, when you only get two showersa week and gulls have been making theirexcremental “mark” on you for threedays straight, you learn to make everydrop count. My project really broadenedmy horizons, because I was able to researchtwo radically different kinds ofanimals. Thanks to the opportunity toconduct fieldwork at Shoals, I plan tokeep studying the secret and surprisingdynamics between ants and birds.Luke DeFisher is a junior in the Ecologyand Evolutionary Biology department atCornell University.By Pat Leonard<strong>For</strong> three jam-packed days in August,10 teen birders came to theCornell Lab of Ornithology for ourYoung Birders Event. Each year wegather some of North America’s tophigh-school-age birders here to encouragethem in their hobby and showwhere it might lead. This year’s brightyoung birders came away thrilled withwhat one called a “life-changing” experience.The only downside, said another,was having to spend time sleepinginstead of birding.When they weren’t tackling toughfield identifications, students touredthe Lab, visited the Cornell UniversityMuseum of Vertebrates, and learnedfrom Macaulay Library experts abouthow to record video and sounds ofbirds. Scientists and graduate studentsshared stories of cutting-edge scienceand how they turned their passion forbirds into rewarding careers.By Anne James RosenbergTwo weeks after our Young BirdersEvent (see above), 12 middleschoolers gathered at the Cornell Labof Ornithology for what we like to thinkof as a “Very Young Birders Event.”Wearing borrowed binoculars aroundtheir necks, they watched a Great BlueHeron hunting in a pond, saw its nesthigh in a dead tree, glimpsed a migratingOlive-sided Flycatcher, and heardthe squeaks of a flock of Cedar Waxwingsas they foraged on berries.Officially called EnvironmentalExploration Days, the occasion wasa weeklong camp that allowed theyoungsters to explore local naturalcommunities and empowered themBy Pat LeonardThe Greek goddess ofwisdom is doing herbit to support modern-dayresearch at the Cornell Labof Ornithology. The AthenaFund, established in 2010 byan anonymous donor and recentlyrenewed for 20<strong>11</strong>–12, offers fundingto help graduate students unravelornithological mysteries.In Athena’s first year, seven studentsreceived awards to continue their research.Daniel Baldassarre tramps theAustralian outback to study the breedingbehavior of Red-backed Fairywrens.Caitlin Stern does genetic detective workto learn how often Western Bluebirdsstray from their mates.Nancy Chen studies genetics and diseasein rare Florida Scrub-Jays, and TazaSchaming studies the impact of dwindlingnumbers of whitebark pines onClark’s Nutcrackers in the Greater YellowstoneEcosystem.The Athena Fund made it possible forNate Senner to set up research camps inAlaska and Manitoba, Canada, so he couldrecover Hudsonian Godwits he had taggedwith geolocation tracking devices at thoselocations during previous summers.Stretching Their WingsTeenage birders hone skills, shape futures at Young Birders EventTen sharp young birders honed their skills with eclipse-plumage ducks during one ofthe Young Birders Event field trips.Eric Gulson, 18, of Veracruz, Mexico,arrived not just for the event, butready to start his first semester atCornell, where he joins two previousyear’sparticipants. There’s a methodto our madness—we get first crack attraining future ornithologists and conservationleaders. Gulson is alreadylending his knowledge to our eBirdproject as a work-study student.Sixteen-year-old Sam Brown, ofChickisaw Trail, Oklahoma, said hisGrowing Their Feathers“ultimate ornithological dream” wouldbe to conserve the prairie habitat andbirds of southern Oklahoma. David Weber,17, of Newfield, New Jersey, said “Iexpect birds to be my life in the future.”And we’d like to help. The YoungBirders Event happens every year inAugust. If you know of a promisingyoung birder in grades 9 through 12,tell them about it or contact JessieBarry at jb794@cornell.edu to findout more.to protect these beautiful places. Thecamp was spearheaded by Cornell CooperativeExtension and included educatorsfrom three other local naturecenters.The students traversed the Ithacaarea on day trips, including a boat rideon Cayuga Lake, hikes through Ithaca’sfamous gorges, a visit to the CornellPlantations gardens and arboretum,and a tour of a water-treatment plant.On their visit to the Cornell Lab,the students started with a game of 20questions from our BirdSleuth afterschoolcurriculum: each child had amystery bird taped to his or her back,and they quizzed each other to deducetheir identity. Next they checkedout binoculars and jumped right intolearning the American Goldfinches,Blue Jays, and Northern Cardinals thatgathered at our visitor center birdfeedinggarden.On a walk around our SapsuckerWoods Sanctuary, the students comparedthe woods, shrubby tangles, andwetlands they saw along the trails, andthen took a turn at mapping their ownbackyards in our online YardMap project.At the end of the day, a brainstormingsession about the week’s environmentalissues led to groups of studentsdesigning action plans for each of thetop three issues.New Athena Fund Powers Graduate ResearchTaza Schaming pauses to take notes while studying Clark’s Nutcrackers in Wyoming.In Papua New Guinea, Ben Freemanhopes to understand the restrictedpatterns of bird occurrence in tropicalmountains—and has helped discover sixbird species previously unknown to themountain range where he works.Yula Kapetanakos is investigating thecritical declines of three Asian vulturespecies. Earlier this year she traveled tonorthern Cambodia to collect feathersamples for DNA analysis. “I was invitedto present my work to the CambodianMinistry of Environment,” she said. “Thiswas quite an honor!”The Athena Fund also focuses on students’personal growth during this formativetime in their scientific careers—and plants in them the idea that they mayone day give back to students themselves.Taza Schaming summed it up this way:“I feel very lucky that I have reached aplace in my life where I am able to followmy passion, where I can make importantcontributions to conservation and ecology,and can learn so much every day, whilehaving the opportunity to teach others.”Jessie BarryPocholo Martinez; Owl illustration by Ann-Kathrin Wirth

Backyard <strong>Birds</strong> Open a Window on ScienAcross the continent, Project FeederWatch celebrates a quarter-century of feeding curiosityIf you keep bird feeders, you're keepingan eye on the natural world—andyou can use what you see to help extendthe reach of science. More than 15,000people do that each year as part of ProjectFeederWatch, which begins its <strong>25</strong>th year onNovember 12. The combined data all thoseFeederWatchers have sent in—on just over100 million individual birds so far—havemade it a resoundingly successful citizenscienceproject.The data have helped scientists understandthe rhythms of bird irruptions, tracethe course of emerging diseases, and get ahandle on sudden population changes, likethe seemingly unstoppable expansion of theEurasian Collared-Dove or, more worryingly,the unexplained decline of the magnificentEvening Grosbeak.Over the years, FeederWatchers have beenLearn more: www.feederwatch.orgprivy to many memorable sightings, frommisguided European finches turning up inNorth America to the perennial anticipationof the winter's first siskin, redpoll, crossbill,or nuthatch.FeederWatch takes the memories andhighlights at your own feeder and, by combiningthem with thousands of others, findsextra meaning in them. To date, nearly twodozen peer-reviewed scientific publicationshave drawn on Project FeederWatch data toexplore subjects including seed choice, diseasedynamics, predation by cats and hawks,and the emerging effects of climate change.If you're already a FeederWatcher, thankyou for helping us understand winter birdsbetter. To the millions of others who keepfeeders, we extend a warm invitation to jointhe project and take part in what has becomean annual pleasure for many participants. Dark-eyed Junco (slate-colored form) Left to right: American TreeSparrow, White-crowned Sparrow,White-throated Sparrow Top to bottom: Chestnut-backed Chickadee,Carolina Chickadee, Black-capped Chickadee,Mountain ChickadeeVariations on a ThemeIf you've got a feeder, you've probably gota chickadee. But which one? Feeder birdsare a celebration of diversity and unity,joining a continent in shades of jays,bluebirds, towhees, and chickadees. Hairy WoodpeckerGetting Help with Similar SpeciesSoon after FeederWatch began, people started askingus for help with tough identifications. So we started aTricky Bird IDs webpage to help people with Downy andHairy woodpeckers, House, Purple, and Cassin’s finches,and other easily confused species. It was a hit—our accipiterpage alone is the third-most-visited page on the FeederWatchsite, with more than 60,000 views per year.Timelines: A Quarter-Century of PerspectiveThere's only one way to discover a long-term trend, and that'sto collect data for a long time. Below, three species illustrate threekinds of population trends revealed by Project FeederWatch data. Downy Woodpecker Sharp-shinned Hawk(not to scale)Seed Preference TestsIn 1993 a study finally put hard numbers to the question ofwhat kinds of seed birds like. FeederWatchers sent data from5,000 locations, helping our researchers discover that whereasblack oil sunflower seed is beloved among tree-living birdssuch as chickadees and finches, ground-foragers such asMourning Doves and many sparrows are more fond of millet.Even red milo has its place, edging out sunflower and milletin the choices of Gambel’s Quail, Curve-billed Thrasher, andSteller’s Jay.Predation at Your FeedersA 1994 study found that predators probably donot kill any more birds at feeders than elsewhere.The most common predators atfeeders were Sharp-shinned and Cooper'shawks, closely followed by domesticcats. Window strikes outpaceddeaths from predation,highlighting the importanceof good feeder placement. Cooper’s Hawk(not to scale) Varied Thrush Pine Siskin Dark-eyed Junco (Oregon form)Top MoversIn the last <strong>25</strong>matically expbellied Woodphave pushedlarly spend wisibly becausegrowing popuUnderstanding IrruptionsPart of feeding birds is guessing what wshow up each year. Irruptions—large-scmovements that don't happen every year—ahard to pin down. Are high counts part omajor invasion—or do you just happen to hathe best seed on your block? FeederWatch dare great for delineating such patterns. Studpublished in 1996 and 1999 clarified irrupticycles in Varied Thrushes and winter finchePercentage ofFeederWatchers504030201001987Song SparrowEvening GrosbeakCommon RedpollLines show the percentage of FeederWatchers reporting each species, a measureof continentwide abundance.1990 1995 Song SparrowBLUE: Some birds, such as the Song Sparrow, have stable populations and areregularly seen.<strong>BirdScope</strong> Vol. <strong>25</strong> (4) <strong>Autumn</strong> 20<strong>11</strong>

cePresenting the<strong>All</strong>-Time #1 Feeder BirdAt feeders all over the continent,one bird towers above allothers, at least in terms of occurrence.The Dark-eyed Juncovisits more than 80 percent ofall FeederWatchers in any givenyear. In any of its forms (the“slate-colored” and “Oregon”are the most widespread), thisplucky little snowbird is the perennialfeeder champion.What’s in the FeederWatch Kit?Project FeederWatch is a winter-long survey, andanyone can do it: children, families, teachers andstudents, retirees, coworkers on lunch breaks, naturecenters, and more. Participants count birdsat their feeders from November to early April ontwo consecutive days as often as once a week, thensend us their data. Join up and we'll send you a kitwith everything you need:• Handbook and instructions with tips forattracting birds to your yard.• FeederWatch calendar for planning countdays, illustrated with participants’ photos.• "Common Feeder <strong>Birds</strong>" poster withmore than 30 illustrations by field-guideartist Larry McQueen, including manyof those on this page.• Access to the FeederWatchforums, where participants share,discuss, and exchange help.A small annual fee, aboutthe price of half a bag ofsunflower seed, providesessential support for staff time, websitemaintenance, data analysis, and materials. Red-bellied Woodpecker White-breasted Nuthatch Eurasian Collared-DoveHow Many <strong>Birds</strong> Could You See?The more you look at your feeders, the more speciesyou'll see. Though northern winters are quiet,several dozen species are still the norm at manyfeeders. Farther south, winter can mean peakbirding—Arizona reports 85 species on its Feeder-Watch list.* No matter where you are, we needyour data to help fill in trends in occurrence anddistribution. In particular, the states of Nevada andHawaii need more participants.Number of speciesseen by at least 5%of participants70*Figures reflect the total number of species reported by at least5 percent of FeederWatchers in each state or province. Red-breasted Nuthatch<strong>All</strong> illustrations by Larry McQueen except:Eurasian Collared-Dove by Evaristo Hernandez-Fernandez; Sharp-shinned and Cooper’s hawks by Evan Barbouryears, a few birds have draandedtheir ranges. Redeckersand Carolina Wrensnorthward and now reguntersin New England, posofchanging climate or thelarity of birdfeeding.illaleref aveataiesons. Steller’s Jay Blue JayMonitoring DiseaseFeederWatchers have been indispensableat discovering and tracking bird diseases.In 1994 they discovered House Fincheye disease, which cut the eastern NorthAmerican population of House Finches inhalf as it spread across the continent. FeederWatchershelped track West Nile virusas it spread, too, and in 2002 their datahelped estimate the disease's heavy toll oncrows and jays. Since then, FeederWatchershave been equally crucial in recordingpopulation recoveries. Carolina Wren House Finch Eastern Towhee American RobinThe Dove No One SawComingOne of the most common birdsat feeders today—the EurasianCollared-Dove—wasn’t even inyour field guide when FeederWatchstarted. In the early 90s it was a curiositymostly restricted to south Florida.Since then it has rocketed acrossthe continent, appearingeverywhere except theNortheast. Last year, aFeederWatcher evenrecorded one in Alaska.You’ll Likely See More Than You ExpectA host of common birds come to feeders (see map,above, for the number of species that visit feeders inyour area). Each year FeederWatchers find the unexpectedtoo, from escaped parrots to national rarities.PFWchecklist No.1,000,000received American Goldfinch(transitional) Northern FlickerBusting the Top Five Myths<strong>About</strong> FeederWatch1. Ho-hum days are important data. “Predictable”counts are at the heart of FeederWatchdata—it’s exciting to report a rare bird, butcounting common birds—or even no birds—isevery bit as important.2. Robins aren’t just birds of spring. We thinkof robins as a sign of spring, but many gatherinto large, nomadic flocks in winter, even farin the north. You could see them at any time.3. Feeding birds won’t delay their migration.The main trigger for a bird’s migratory urge isday length. When it’s time to go, your feederswon’t keep birds from leaving—but they mightgive them the energy to go.4. <strong>Birds</strong> don’t get addicted to feeders. <strong>Birds</strong>may visit your feeder every day, but they actuallyget most of their food from natural sources.5. You are allowed to take your eyes off yourfeeder. Lots of people travel for the holidays.If you’ll be gone for part of the winter, you canstill collect valuable data during the time thatyou’re home.Evening Grosbeak Declines<strong>Birds</strong> move over vast areas, making population changesimpossible to detect from isolated counts. Widespread,long-term records like those of Project FeederWatchare essential for distinguishing normal population fluctuationsfrom true declines. FeederWatchers’ data havehelped researchers document this spectacular bird’sdecline—a 50 percent drop in the number of locationshosting this species over 20 years—giving us a handle onthe problem. Evening Grosbeak Common Redpoll2000 2005 2010RED: Common Redpolls, like many seed-eating finches, are irruptive species—every couple of years they range widely in response to changes in food supplies.FeederWatchers help map these irruptions across the continent.2012YELLOW: In the 1990s, Evening Grosbeaks showed an irruptive pattern similarto Common Redpolls, but by the 2000s overall counts were much lower, withless year-to-year fluctuation.

6 <strong>BirdScope</strong> Vol. <strong>25</strong> (4) <strong>Autumn</strong> 20<strong>11</strong>Musical interludeConcerto for Wood Thrush and OrioleThe composer who brought dawn chorus into the concert hallJanet HeintzBy Sharinne SukhnanandMost birders carry a notebook with them tojot down observations or to quickly sketch abird they see—but one French bird watchersketched the songs themselves, using his incredible earto transcribe nature’s notes onto a musical staff. Thatman was Olivier Messiaen (1908–1992), one of the greatcomposers of the twentieth century.Messiaen’s unique talent emerged early. As a boy, hehoned his ear listening to and transcribing the songsof birds at his aunt’s farm in the French countryside.He first used birdsong in his work during the darkestperiod of his life: while imprisoned in a German prisoner-of-warcamp during World War II, Messiaen composedand then conducted, with a prisoners’ quartet,Quatuor pour la Fin du Temps (Quartet for the End ofTime, 1941). One of his most celebrated and importantcompositions, the somber piece includes stylized songsfrom the Eurasian Blackbird and the Common Nightingale.The third movement, Messiaen later remarked,represents the “abyss of time, its sadness and weariness.But contrasting this theme are the birds, who arethe opposite of time; they are our desire for light, forthe stars, and for all things sublime.”Although he was most familiar with the Old Worldbirds of his home country, Messiaen included birdsfrom all over the world in his works. When he wantedto include North American birds for Oiseaux Exotiques(Exotic <strong>Birds</strong>, 1956), he turned to recordings from theCornell Lab of Ornithology. As part of his research,Messiaen used the first publicly available audio guideto North American birds, American Bird Songs, a set of78-rpm phonograph records released by the CornellLab in 1942. Messiaen visited the Cornell Lab in the1970s, shook hands with then-director Douglas Lancaster,and listened to recordings in what is now knownas the Macaulay Library.Messiaen’s keen ear lent a unique flavor to the fieldnotes that were the building blocks of his compositions.In a 2005 biography, by Peter Hill and Nigel Simone,Messiaen said, “The voice of the Cardinal is brilliantand pearly. The oscillations resemble a NightingaleFrequency (kilohertz)Time (seconds)Turning birdsong into music: Messiaen transcribed theWood Thrush’s three-part song (shown as a spectrogram,or plot of the sound’s pitch against time, top) intocorresponding phrases for the musical scale (bottom),instructing the musicians to laissez vibrer (let it vibrate) forthe final trilling phrase. Spectrogram from <strong>Birds</strong> of NorthAmerica Online; music from Oiseaux Exotiques ©1959Universal Edition (London) Ltd., London/UE 13008.when quiet, and the drumming of a Great-spottedWoodpecker when loud.” He described a crow as, “raucous,powerful, sneering, sarcastic.”When it came time to transcribe what he’d heard tothe page, Messiaen took great care. His wife Yvonne Loriodtape-recorded many of their walks, helping Messiaento double-check his transcriptions. Still, someadjustments were inevitable. Speaking with anotherbiographer, Claude Samuel, Messiaen described someof the challenges: “A bird being much smaller than weare, with a heart that beats faster and nervous reactionsthat are much quicker, sings in extremely swift tempos,impossible for our instruments. <strong>Birds</strong> also sing in extremelyhigh registers that cannot be reproduced.” Tomake bird songs playable on musical instruments, Messiaenslowed their cadences, transposed high pitches tolower octaves, and adjusted the birds’ tiny pitch differences.The result was a new kind of musical language,using new scales and structures.Despite these alterations, Messiaen had a gift forevoking birds in their native habitats. In 1972, Messiaenwas commissioned to compose a piece celebrating thebicentennial anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.He traveled to Bryce Canyon, in Utah, and foundinspiration for the resulting work, Des Canyons auxÉtoiles (From the Canyons to the Stars, 1974). In thisambitious piece, Messiaen captured the majestic qualityof Utah’s canyonlands: the rich multicolored hues ofthe canyon walls, the dry desert wind, the sparkle of thenighttime stars, and the birds. The Northern Mockingbird,the Wood Thrush (even though it’s not traditionallya bird of Utah canyons), and the orioles each haveentire movements devoted to them. The overall effectis colorful, mysterious, and ultimately, awe-inspiring.Sharinne Sukhnanand is a writing intern at the Cornell Lab,and an electronic musician based in Ithaca, New York.2012 Upcoming Birding Eventsand FestivalsThe sapsuckerJanuary 12–15Wings Over Willcox Birding andNature FestivalWillcox, Arizona800-200-2272Connie Bonner, questions@wingsoverwillcox.comwww.WingsOverWillcox.comJanuary <strong>25</strong>–3015th Annual Space Coast Birdingand Wildlife FestivalBrevard Community College, North CampusTitusville, Florida321-268-5224, 800-460-2664Neta Harris, neta@brevardnaturealliance.orgwww.spacecoastbirdingandwildlifefestival.orgJanuary 26–29Snow Goose Festival of thePacific FlywayChico, California530-345-1865info@snowgoosefestival.orgwww.SnowGooseFestival.orgFebruary 3–5Cape Ann Winter Birding WeekendGloucester, Massachusetts(978) 283-1601Tim Burton, tim@capeannchamber.comwww.CapeAnnChamber.com/birdingweekendSponsored Listingsindicates the Cornell Lab will attend this festival. Please join us!February 9–<strong>11</strong>Eagle ExpoMorgan City, Louisiana985-395-4905, 800-<strong>25</strong>6-2931Carrie Stansbury, info@cajuncoast.comwww.cajuncoast.comFebruary 17–19Winter Wings FestivalKlamath Falls, Oregon877-541-BIRD (2473)info@winterwingsfest.orgwww.winterwingsfest.orgFebruary 23–2616th Annual Whooping CraneFestivalPort Aransas, Texas 78373361-749-5919 or 800-45-COASTinfo@portaransas.orgwww.WhoopingCraneFestival.orgFebruary <strong>25</strong>10th Annual SW Florida BurrowingOwl FestivalRotary Park, Cape Coral, Florida239-980-<strong>25</strong>93support@ccfriendsofwildlife.orgwww.ccFriendsofWildlife.orgMarch 1–4San Diego Bird FestivalSan Diego, California858-273-7800David Kimball, birdfest@cox.netKaren Straus, kstraus1@gmail.comwww.SandieGoAudubon.orgMarch 2–4International Festival of OwlsHouston, Minnesota507-896-HOOT (4668)Karla Bloem, nature@acegroup.ccwww.FestivalofOwls.comMarch 30–April 1Olympic Peninsula BirdfestSequim, WashingtonThe 16th Annual San Diego Bird FestivalMarch 1–4, 2012Keynote Speaker: Kenn KaufmanSpecial Guest: Richard CrossleyPelagic Birding, Birding field tripsto Mountains, Desert, Shore, and CoastalWetlands—plus Birding by Bike or Kayaknew! field tripsnew! workshopsBirding & Optics EXPOplus! FAMILY FREE DAY events on SundayInformation and Registration:sandiegoaudubon.org or call 858-273-7800new! post-festival trip to lush and birdyCOSTA RICA, March 5–12, with San DiegoAudubon Society and Holbrook Travel:www.holbrooktravel.com/SDAS/866-748-6146

<strong>BirdScope</strong> Vol. <strong>25</strong> (4) <strong>Autumn</strong> 20<strong>11</strong> 7coast to coastBy Marshall IliffAs destructive and dangerous as theycan be, hurricanes can make for legendarybirding. Strong winds push seabirdsfrom tropical waters to northernshores or far inland—and these days birdersare primed to find them, using smartphonesto stay on top of weather forecastsand safety warnings, and to instantlytrade sightings. After a storm passes, theeBird project, jointly run by the CornellLab of Ornithology and Audubon, providesa single location for storm sightingsto be collated, mapped, and studied.I waited out Tropical Storm Irene onthe shores of Quabbin Reservoir, centralMassachusetts. As the storm approached,the rain pelted and the winds slowly intensifiedto about 45 mph by about 1:00p.m. That’s when my friends and I sawour first storm bird—a Parasitic Jaeger—and next a flock of Hudsonian Godwits.Around 4:00 p.m., a few Black Ternsand two distant jaegers signaled a shiftin the wind. The next hour of birdingwas one of the most exciting of my life.An odd bird high in the sky baffled meat first, but it turned and revealed a longtail—an adult White-tailed Tropicbird, atleast 800 miles from home! Next, an adultSooty Tern flew through my field of view.Sooty Terns range widely, but they’renever seen north of the Carolinas exceptduring storms. I had half-expected to seethe terns, but was completely shockedby the tropicbird. My day was capped offwith an incongruous sighting of a Leach’sStorm-Petrel, usually an open-ocean birdthat stays low to the water, flying high inthe sky and heading south over the woods.Hurricane Irene turned into a trulyhistoric storm for birders, as hundreds ofeBird reports filed from the storm’s pathmade clear. It was the best storm everWindswepteBird users find rare visitors in storms’ pathsBirders in Cape May, New Jersey, bravedIrene’s winds and were rewarded withthree White-tailed Tropicbirds. Cornellalum Tom Johnson caught two at once inhis camera frame.for White-tailed Tropicbirds—a total of14 showed up, one getting as far as NewHampshire. Sooty Terns—the quintessentialstorm bird—were seen in a dozenstates; similar-looking Bridled Ternswere displaced as well, but as in previousstorms they stayed along the coasts.Leach’s and Wilson’s storm-petrels appearedfar inland. Grounded shorebirdswere seen all over, with Hudsonian Godwitsbeing the star attraction. Irene alsobrought two non-seabird rarities: a BlackSwift to New Jersey (most likely from asmall population in the Caribbean) anda Great Kiskadee to New York City. Bothwere first records for the East Coast.With sightings from Irene and TropicalStorm Lee (which struck the GulfCoast the week after) so well documentedin eBird, the storms of 20<strong>11</strong> may offer newinsights into how storms affect birds. Weknow that size, strength, path, and speedof a storm all have different effects, andwe look forward to exploring the detailsmore fully. Thanks to everyone who contributessightings—rare or mundane—towww.ebird.org.Tom JohnsonSapsucker Woods Society A legacy for science, conservation, and educationA planned gift in the form of a bequest or life income agreement is an idealway to plan for your future, benefit your family, and extend theLab’s mission of bird research and conservation.By Anna AutilioTo study the behavior of AcornWoodpeckers in northern California,one must study the acorns.Walter Koenig, senior scientist at theCornell Lab of Ornithology, has beeninvestigating these unusual, communallybreeding woodpeckers for morethan 30 years, and he’s still turning upsurprises about why some birds forgobreeding on their own and choose tohelp others raise their young.Acorn Woodpeckers live in groupsof up to 15 individuals, but only ahandful of these actually breed. Theothers help group survival by tendingnestlings and storing thousands ofacorns in granary trees for the winter.Because of complicated relationshipsin a colony—up to seven males competefor the affections of two or threefemales—the helpers aid in raisingtheir own siblings or half-siblings.In a recent paper in AmericanNaturalist, Koenig and his colleaguesdescribed an unexpected finding: thehelper woodpeckers seem to improvethe group’s breeding success mostwhen the acorn crop is good, and lesswhen it is poor. Previously, scientistsIt’s also simple to establish: contactScott Sutcliffe (607-<strong>25</strong>4-2424) oremail cornellbirds@cornell.eduto find out more.Helpers Help in Times of Plentyhad found that helpers in other speciesprovide more benefit when timesare difficult, gathering more foodwhen it is harder to come by. Koenig’sresult is surprising because thegroups clearly benefit from helpers’aid when acorns are plentiful.“A lot more birds are born in goodyears than bad years,” Koenig said.When there’s plenty of food to goaround, the woodpeckers benefit byhaving lots of birds to store food andlater feed it to the young. But in leanyears, the group doesn’t do as wellbecause helpers eat what scarce foodis present, leaving less for future reproductionefforts by the group.The yearly crop of acorns is highlyunpredictable, so to determine agood crop year from a bad one, theacorns themselves had to be tallied.“We had to go do it ourselves,” saidKoenig, who has conducted an acornsurvey every year since 1980. Acornsmay not have been what the scientistsoriginally expected to study, butthe accumulated numbers have sheda great deal of light on their real researchsubjects.360-683-7265Bob Hutchison, rbrycehut@wavecable.comwww.OlympicBirdfest.orgApril 12–15Galveston FeatherFestGalveston Island, Texas832-459-5533NatureTourismGalv@juno.comwww.GalvestonFeatherFest.comApril 27–30Balcones Songbird NatureFestivalBalcones Canyonlands NWR512-965-2473Cathy Harrington, friends@friendsofbalcones.orgwww.BalconesSongbirdFestival.orgApril 30–May 5New River Birding and NatureFestivalNew River Gorge National RiverFayetteville, West Virginia304-574-4<strong>25</strong>8Dave Pollard, goshawk@birding-wv.comwww.birding-wv.comMay 3–6Georgia Mountain BirdFestUnicoi State Park and LodgeHelen, Georgia706-878-2201, ext 305Ellen Graham, ellen.graham@dnr.state.ga.uswww.gamtnbirdfest.comMay 10–13Kachemak Bay Shorebird FestivalHomer, Alaska907-235-7740Christina Whiting, shorebirdster@gmail.comwww.HomerAlaska.orgBalconesSongbirdNature FestivalAPRIL 27~30, 2012Texas Hill CountryBird and Nature Toursregistration begins Feb. 15Sunday ~ FREE Family EventsBalcones CanyonlandsNational Wildlife Refugebalconessongbirdfestival.orgMay 12NJ Audubon World Series of BirdingCovers the entire state of New Jersey609-884-2736Sheila Lego, birdcapemay@njaudubon.orgwww.WorldSeriesofBirding.orgMay 18–24Cape May Spring WeekendCape May, New Jersey609-884-2736Sheila Lego, birdcapemay@njaudubon.orgwww.BirdCapeMay.orgMay 27–30Down East Spring Birding FestivalCobscook Bay Area, Eastern Maine207-733-2233Kara McCrimmon, birdfest@thecclc.orgwww.DownEastBirdfest.orgMay <strong>25</strong>—28, 2012: Come bird in Maine at the annualDown East Spring Birding FestivalFresh Water and Ocean Boat ToursGuided Hikes ~ Expert Talks ~ More!Moosehorn National Wildlife RefugeMachias Seal Island ~ Pristine Cobscook Baywww.downeastbirdfest.orgbirdfest@thecclc.org207-733-2233Call or email: Cobscook Community Learning Center, Trescott, ME 04652May 31–June 314th Acadia Birding FestivalMount Desert Island/Bar Harbor/SouthwestHarbor, Maine207-288-8128Michael J. Good, info@acadiabirdingfestival.comwww.AcadiaBirdingFestival.comThank You,Lab SponsorsThe support we receive fromsponsors helps ensure our continuedsuccess. <strong>For</strong> more information aboutbeing a Lab sponsor, contactMary Guthrie at msg21@cornell.edu.Aspects, Inc.BirdJamBirdola ProductsCHS Sunflower, Inc.Droll YankeesThe HummKayteeLindblad ExpeditionsLyric Wild Bird FoodPine Tree Farms, Inc.America’s Pet StoreSwarovski OptikWild <strong>Birds</strong> Unlimited(corporate headquarters)Wild <strong>Birds</strong> Unlimited(Sapsucker Woods)

WB01052<strong>11</strong> | ©20<strong>11</strong> KAYTEE Products, Inc.Left: “Oregon” Junco by Darin Ziegler;Right: “Slate-colored” Junco by Gerry SibellBlue Jay by Michaela Fotheringham159 Sapsucker Woods Road, Ithaca, NY 14850-1999www.birds.cornell.eduBecome a member of the Lab!Call (800) 843-2473 (in the U.S.) or (607) <strong>25</strong>4-2473.brief encountersIn southwest Colorado, outside Ouray,lies Box Canyon, a small, dramaticcanyon that is one of the best places tosee Black Swifts in North America. Thismysterious species—a large swift thatfeeds on flying insects and whose nestwas not discovered until 1901—travelseach year from Central and SouthAmerica to its clandestine nestinggrounds in canyons and waterfalls ofthe West. In Box Canyon, a small collectionclings to mossy crevices besideand behind the flowing waterfall.I came here to document the breedingbiology of this rarely filmed speciesfor the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’sMacaulay Library video archive. <strong>For</strong>Keeping an Eye on the Usual SuspectsThey’re common birds. But are they hiding something?By Hugh PowellAh, fall migration! Skeins of geese, confusing fallwarblers, winter sparrows. Blue Jays.“Most people don’t even think of Blue Jays as beingmigratory,” said Chris Wood, co-project leader for eBirdat the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Though many jays do stayput for the winter, some individuals head south, a patterncalled partial migration. Uncovering such hidden routinesamong common birds is one of the most rewarding aspectsof bird watching, Wood said.Each fall Wood looks forward to watching hordes of jaysmigrate along nearby Cayuga Lake, where he has been keepingnear-daily watches for five years running. In a singlemorning last year he counted 2,486 Blue Jays, each one patientlyflapping southward just above the treetops.“Ironically, we know less about what influences thesemovements of common birds than we do about somethingrare like a Cave Swallow,” Wood said. “In late October I’llbe able to look at the weather and tell you when to go outand look for the first Cave Swallow in the Northeast.” Butbecause Blue Jays, flickers, chickadees, and the like are ubiquitousall year, it’s much less apparent when they’re moving.It gets even more tricky with birds like Blue Jays that may flylong distances to gather acorns or other foods, then return totheir home territories for the night.Records show plenty of other familiar species move enmasse, too: counts of 36,000 Black-capped Chickadees onthe Lake Ontario shore in 1961; 5,000 Northern Flickersskirting a Cape May, New Jersey, beach in 1937; <strong>11</strong>,000 CedarWaxwings in Duluth, Minnesota.It’s easy to recognize migration when strange warblersappear in hedgerows or Dark-eyed Juncos show up at feeders.But lots more migration is happening right under ournoses, Wood said—if we just keep track (see sidebar). Thebirds are here all the time, living their lives and waiting forsomeone to uncover their secrets.If a daily jaunt to your favorite patch doesn’t fit your schedule,you can even start at the feeders right outside your window.Project FeederWatch’s more than 15,000 participants havebeen fueling scientific discoveries for <strong>25</strong> years (see pp. 4-5).Benjamin M. ClockSwift Water, Swift Nestfour days I perched on a windingcatwalk that leads sightseersacross the sheer rock face andup to the waterfall. Black Swiftsbegin nesting in late summer,and upon my arrival in earlyJuly I found a clear view of onefemale sitting on her cliff-facenest, brooding a single recentlylaid egg. Visitors peered into thedepths of the canyon hoping toglimpse the swifts—and I was happyto offer them a close-up view with mycamera’s 80-power lens.<strong>For</strong> those four days I filmed thefemale as she incubated her egg andtended to her nest. At one point, Ifilmed her as she flew farther up thecanyon to gather fresh moss from theedge of the waterfall and add it to therim of her nest. You can see a sampleclip from my visit at www.bitly/MLblackswift.—Benjamin M. ClockHas this Blue Jay beenout gathering acorns, oris it migrating? Watchingcommon birds closely canreveal clues about whatthey’re up to.Make Your Outings Count1. Location: Look for hilltops with a good view orwoods near natural barriers. Even fairly smalllakes or rivers present an obstacle to forest birds.2. Consistency: Pick a place and make it yours. Repeatedvisits help you learn what’s normal, eventuallyrevealing what’s not normal.3. Behavior: If you see birds doing something new,look for the reason. “Usually you don’t see localbirds in sustained flight over the tops of trees—usually they’re in the trees,” Wood said. That canbe a clue you’re seeing migrants.4. Recordkeeping: Wood can still recall the greatBlue Jay migration of 2010: 2,486 in one morning.Or a November 1999 count of more than 1.<strong>25</strong> millionAmerican Robins in Cape May, New Jersey—but only because he kept notes each day, revealingpatterns over time.5. Sharing: Citizen-science projects like eBird andProject FeederWatch are a great way to instantlypass your sightings along to the scientific community,where they can become part of something larger.Fact: To conserve energy during thecold winter nights birds go into amini-hibernation called torpor. Torporis a kind of deep sleep accompanied bydrastically lowered body temperature,heart rate, and breathing. But just howthey do this is still a mystery.CMYCMMYCYCMYKWB01052<strong>11</strong>_BrdScpe_Ad_HR.<strong>pdf</strong> 1 8/<strong>11</strong>/<strong>11</strong> 2:36 PMTufted TitmouseWinterize Your Backyard. Cold temps and harsh weather make it even moreimportant to feed wild birds. KAYTEE’s energy-boosting products are a great sourceof nutrition when the natural food supply becomes scarce. With high fat content andseeds that are high in oil, KAYTEE ® products help birds prepare for long winter nightsand survive the cold days.Helping your backyard birdssurvive the cold months!Find out about all of our products in the Wild Bird section at kayteewildbirds.com