the cultural formulation: a method for assessing cultural factors

the cultural formulation: a method for assessing cultural factors

the cultural formulation: a method for assessing cultural factors

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Psychiatric Quarterly, Vol. 73, No. 4, Winter 2002 ( C○ 2002)<br />

THE CULTURAL FORMULATION: A METHOD<br />

FOR ASSESSING CULTURAL FACTORS<br />

AFFECTING THE CLINICAL ENCOUNTER<br />

Roberto Lewis-Fernández, M.D.<br />

and Naelys Díaz, M.S.W.<br />

The growing <strong>cultural</strong> pluralism of US society requires clinicians to examine <strong>the</strong><br />

impact of <strong>cultural</strong> <strong>factors</strong> on psychiatric illness, including on symptom presentation<br />

and help-seeking behavior. In order to render an accurate diagnosis across<br />

<strong>cultural</strong> boundaries and <strong>for</strong>mulate treatment plans acceptable to <strong>the</strong> patient,<br />

clinicians need a systematic <strong>method</strong> <strong>for</strong> eliciting and evaluating <strong>cultural</strong> in<strong>for</strong>mation<br />

in <strong>the</strong> clinical encounter. This article describes one such <strong>method</strong>, <strong>the</strong><br />

Cultural Formulation model, expanding on <strong>the</strong> guidelines published in DSM-IV.<br />

It consists of five components, <strong>assessing</strong> <strong>cultural</strong> identity, <strong>cultural</strong> explanations<br />

of <strong>the</strong> illness, <strong>cultural</strong> <strong>factors</strong> related to <strong>the</strong> psychosocial environment and levels<br />

of functioning, <strong>cultural</strong> elements of <strong>the</strong> clinician–patient relationship, and<br />

<strong>the</strong> overall impact of culture on diagnosis and care. We present a brief historical<br />

overview of <strong>the</strong> model and use a case scenario to illustrate each of its<br />

Roberto Lewis-Fernández, M.D., is an Assistant Professor of Clinical Psychiatry at<br />

Columbia University, a Lecturer on Social Medicine at Harvard University, and is <strong>the</strong><br />

Director of <strong>the</strong> Hispanic Treatment Program at NY State Psychiatric Institute, New<br />

York, NY.<br />

Naelys Díaz, M.S.W., is a Doctoral Candidate in Social Work at Fordham University.<br />

Address correspondence to Roberto Lewis-Fernández, M.D., New York State Psychiatric<br />

Institute, Unit 69, 1051 Riverside Drive, New York, NY 10032; e-mail: rlewis@<br />

nyspi.cpmc.columbia.edu.<br />

271<br />

0033-2720/02/1200-0271/0 C○ 2002 Human Sciences Press, Inc.

272 PSYCHIATRIC QUARTERLY<br />

components and <strong>the</strong> substantial effect on illness course and treatment outcome<br />

of implementing <strong>the</strong> model in clinical practice.<br />

KEY WORDS: <strong>cultural</strong> <strong><strong>for</strong>mulation</strong>; diagnostic assessment; <strong>cultural</strong> psychiatry; popular<br />

syndromes; Latinos.<br />

As rising immigration causes industrialized societies to become even<br />

more <strong>cultural</strong>ly pluralistic and organized mental health services in developing<br />

nations face <strong>the</strong> challenge of distributing care more broadly,<br />

psychiatrists will increasingly come in contact with a larger diversity<br />

of social groups (1). The evaluation of patients from disparate ethno<strong>cultural</strong><br />

backgrounds requires clinicians to assess <strong>the</strong> impact of <strong>cultural</strong><br />

<strong>factors</strong> on all aspects of psychiatric illness, including symptom<br />

presentation and help-seeking behavior. In order to render an accurate<br />

diagnosis across <strong>cultural</strong> boundaries and <strong>for</strong>mulate treatment plans<br />

acceptable to <strong>the</strong> patient and oftentimes <strong>the</strong> family, clinicians need a<br />

<strong>method</strong> <strong>for</strong> eliciting and evaluating <strong>cultural</strong> in<strong>for</strong>mation during <strong>the</strong><br />

clinical encounter.<br />

Standardizing <strong>the</strong> assessment <strong>method</strong> is particularly important in order<br />

to avoid systematic misjudgments of which <strong>the</strong> clinician is often unaware.<br />

An example of this is <strong>the</strong> apparent clinician bias that results in<br />

a higher rate of misdiagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia among African<br />

American and Latino patients suffering from bipolar disorder or depression<br />

with psychotic features, compared to non-Latino Whites (2,3).<br />

In one key study, misdiagnosis by race was found to be related to<br />

“in<strong>for</strong>mation variance,” differences in <strong>the</strong> amount of in<strong>for</strong>mation <strong>the</strong><br />

predominantly White clinicians obtained from African American as opposed<br />

to White patients, ra<strong>the</strong>r than race-specific discrepancies in <strong>the</strong><br />

way diagnostic criteria were applied (“criterion variance”) (4). This suggests<br />

that standardizing <strong>the</strong> process of clinical in<strong>for</strong>mation-ga<strong>the</strong>ring<br />

would reduce misdiagnosis.<br />

Using a systematic <strong>method</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>assessing</strong> <strong>cultural</strong> contributions to<br />

illness presentation would also help <strong>the</strong> clinician diagnose <strong>cultural</strong>ly<br />

patterned experiences of illness that are distinct from mainstream psychiatric<br />

diagnostic criteria. Many societies around <strong>the</strong> world have developed<br />

folk mental health classification systems that are distinct from<br />

US psychiatric nosology (5,6). Patients from <strong>the</strong>se societies and <strong>cultural</strong><br />

backgrounds often express distress and psychopathology less in accord<br />

with US diagnostic categories than with <strong>the</strong>ir popular syndromes.<br />

The translation between popular and professional nosologies is often<br />

complicated. Neuras<strong>the</strong>nia, <strong>for</strong> example, originally a US professional

ROBERTO LEWIS-FERNÁNDEZ AND NAELYS DÍAZ 273<br />

diagnosis that is no longer included in <strong>the</strong> DSM system but is retained<br />

in ICD-10, is <strong>the</strong> most prevalent current (12-month) disorder among<br />

Chinese Americans in Los Angeles County (7). For US psychiatrists,<br />

however, it presents a diagnostic challenge, due to its partial overlap<br />

with multiple diagnostic categories, including mood, anxiety, and somato<strong>for</strong>m<br />

disorders (7,8).<br />

Ataque de nervios (attacks of nerves), on which we will focus later<br />

in this article, is ano<strong>the</strong>r example of a popular category that presents<br />

diagnostic challenges <strong>for</strong> US psychiatrists. This Latino syndrome is<br />

characterized by paroxysms of intense emotionality, acute anxiety<br />

symptoms, and loss of control, often associated with dissociative experiences<br />

and occasionally with o<strong>the</strong>r- or self-directed aggressive behaviors<br />

(9). It constitutes <strong>the</strong> second most prevalent psychopathological<br />

syndrome in Puerto Rico and has a complex relationship with psychiatric<br />

diagnoses (10). Mainly associated with mood and anxiety disorders,<br />

it also can occur in conjunction with dissociative disorders (11)<br />

and in individuals with impulse control, somato<strong>for</strong>m, or psychotic disorders.<br />

The existence of <strong>the</strong>se popular syndromes and <strong>the</strong> need <strong>for</strong> a<br />

case-by-case translation into DSM-IV categories underscores <strong>the</strong> risks<br />

of not obtaining sufficient <strong>cultural</strong> in<strong>for</strong>mation as part of <strong>the</strong> diagnostic<br />

assessment.<br />

In order to deliver care that is <strong>cultural</strong>ly valid, <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e, clinicians<br />

need a <strong>method</strong> that systematically allows <strong>the</strong>m to take culture into<br />

account when conducting a clinical evaluation. One such <strong>method</strong> that<br />

has been operationalized in recent years is <strong>the</strong> Cultural Formulation<br />

(CF) model. The CF model supplements <strong>the</strong> biopsychosocial approach<br />

by highlighting <strong>the</strong> effect of culture on <strong>the</strong> patient’s symptomatology,<br />

explanatory models of illness, help-seeking preferences, and outcome<br />

expectations (12–15). It is described in Appendix I of DSM-IV (16) and<br />

is recommended <strong>for</strong> implementation during <strong>the</strong> assessment phase of<br />

every clinical relationship.<br />

The CF model is especially necessary when <strong>the</strong> clinician and <strong>the</strong> patient<br />

do not share <strong>the</strong> same <strong>cultural</strong> background, since it is <strong>the</strong>n that<br />

particular attention to <strong>cultural</strong> features can be most helpful in orienting<br />

<strong>the</strong> clinical intervention. It is important to remember, however, that<br />

even persons sharing <strong>the</strong> same race or ethnicity can differ in <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>cultural</strong><br />

backgrounds, as race and ethnic groups are <strong>cultural</strong>ly heterogenous<br />

(12,17). Implementation of <strong>the</strong> CF model when <strong>the</strong>re is no ethnic<br />

difference between patients and clinicians can still elicit very useful in<strong>for</strong>mation<br />

about <strong>cultural</strong>ly based values, norms, and behaviors—such<br />

as about alternative health practices, physiological interpretations, or<br />

religious beliefs—that may o<strong>the</strong>rwise go unnoticed because <strong>the</strong> clinician

274 PSYCHIATRIC QUARTERLY<br />

assumes that <strong>the</strong> patient is “just like me.” In addition, <strong>the</strong> CF model<br />

should not be construed <strong>for</strong> use mainly between majority clinicians and<br />

minority patients. Given <strong>the</strong> growing ethno-<strong>cultural</strong> pluralism of psychiatric<br />

residency programs in <strong>the</strong> US (including a high proportion of<br />

International Medical Graduates), <strong>the</strong> existence of <strong>cultural</strong> differences<br />

is becoming perhaps just as likely between majority patients and <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

clinicians.<br />

This article will present <strong>the</strong> Cultural Formulation model. The first<br />

part of <strong>the</strong> discussion will give a brief historical overview of <strong>the</strong> model<br />

and its components. The second part will consist of a case scenario that<br />

will illustrate <strong>the</strong> purpose of each section of <strong>the</strong> model and its usefulness<br />

in psychiatry and mental health in general.<br />

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW AND COMPONENTS OF THE<br />

CULTURAL FORMULATION MODEL<br />

The contemporary version of <strong>the</strong> CF model dates from <strong>the</strong> process of<br />

preparing DSM-IV. Due in part to criticisms of insensitivity to <strong>cultural</strong><br />

issues in DSM-III and DSM-III-R, <strong>the</strong> National Institute of Mental<br />

Health supported <strong>the</strong> creation in 1991 of a Group on Culture and Diagnosis.<br />

The main goal of this Group was to advise <strong>the</strong> DSM-IV Task<br />

Force on how to make culture more central to <strong>the</strong> Manual. One of <strong>the</strong><br />

ways proposed by <strong>the</strong> Group was <strong>the</strong> development of a standard <strong>method</strong><br />

<strong>for</strong> applying a <strong>cultural</strong> perspective to <strong>the</strong> clinical evaluation (15,18).<br />

Early ef<strong>for</strong>ts focused on supplementing <strong>the</strong> five existing axes with a<br />

sixth or “Cultural Axis.” However, this approach was soon abandoned as<br />

too limiting, since at best it would only permit <strong>the</strong> use of a restricted list<br />

of socio-<strong>cultural</strong> labels which would be of little clinical significance (14).<br />

The Group aimed <strong>for</strong> a more thorough re-thinking by <strong>the</strong> clinician of<br />

<strong>the</strong> patient’s <strong>cultural</strong> picture and how it affects all five axes, as well as<br />

clinical elements not contemplated by <strong>the</strong> multi-axial structure, such<br />

as help-seeking expectations, family and community views of <strong>the</strong> illness<br />

and its outcome, and institutional pressures on <strong>the</strong> clinical encounter.<br />

A key aim of <strong>the</strong> Group was to operationalize a <strong>method</strong> that,<br />

while standardized, still allowed <strong>for</strong> an individualized assessment of<br />

<strong>cultural</strong> <strong>factors</strong> (15). This was based on <strong>the</strong> perspective that a person’s<br />

<strong>cultural</strong> background is affected by <strong>the</strong> intersection of multiple social<br />

influences—including those due to gender, class, race, sexual orientation,<br />

etc.—and <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e would need to be described in individual ra<strong>the</strong>r<br />

than solely collective terms in order to avoid stereotyping (12).<br />

The Group settled on a narrative <strong>for</strong>mat that follows a standard set<br />

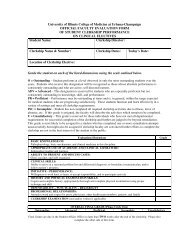

of components. These are listed in Table 1. Every patient would have

ROBERTO LEWIS-FERNÁNDEZ AND NAELYS DÍAZ 275<br />

TABLE 1<br />

Components of <strong>the</strong> Cultural Formulation<br />

Cultural <strong><strong>for</strong>mulation</strong><br />

section<br />

Cultural identity of <strong>the</strong><br />

individual<br />

Cultural explanations<br />

of <strong>the</strong> individual’s<br />

illness<br />

Cultural <strong>factors</strong><br />

related to psychosocial<br />

environment and<br />

levels of functioning<br />

Cultural elements of <strong>the</strong><br />

relationship between<br />

<strong>the</strong> individual and<br />

<strong>the</strong> clinician<br />

Overall <strong>cultural</strong><br />

assessment <strong>for</strong><br />

diagnosis and care<br />

Subheading<br />

• Individual’s ethnic or <strong>cultural</strong> reference<br />

group(s)<br />

• Degree of involvement with both <strong>the</strong> culture<br />

of origin and <strong>the</strong> host culture (<strong>for</strong> immigrants<br />

and ethnic minorities)<br />

• Language abilities, use, and preference<br />

(including multilingualism)<br />

• Predominant idioms of distress through<br />

which symptoms or <strong>the</strong> need <strong>for</strong> social<br />

support are communicated<br />

• Meaning and perceived severity of <strong>the</strong><br />

individual’s symptoms in relation to norms of<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>cultural</strong> reference group(s)<br />

• Local illness categories used by <strong>the</strong><br />

individual’s family and community to identify<br />

<strong>the</strong> condition<br />

• Perceived causes and explanatory models that<br />

<strong>the</strong> individual and <strong>the</strong> reference group(s) use<br />

to explain <strong>the</strong> illness<br />

• Current preferences <strong>for</strong> and past experiences<br />

with professional and popular sources of care<br />

• Culturally relevant interpretations of social<br />

stressors, available social supports, and levels<br />

of functioning and disability<br />

• Stresses in <strong>the</strong> local social environment<br />

• Role of religion and kin networks in providing<br />

emotional, instrumental, and in<strong>for</strong>mational<br />

support<br />

• Individual differences in culture and social<br />

status between <strong>the</strong> individual and <strong>the</strong><br />

clinician<br />

• Problems that <strong>the</strong>se differences may cause in<br />

diagnosis and treatment (e.g. difficulties in<br />

eliciting symptoms and understanding <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

<strong>cultural</strong> significance, in determining whe<strong>the</strong>r<br />

a behavior is normal or pathological, etc.)<br />

• Discussion of how <strong>cultural</strong> considerations<br />

specifically influence comprehensive<br />

diagnosis and care<br />

Note. Summarized from DSM-IV, pp. 843–844.

276 PSYCHIATRIC QUARTERLY<br />

his/her <strong>cultural</strong> background described in a brief text that incorporates<br />

each of <strong>the</strong> listed elements. This Cultural Formulation is based on prior<br />

work on <strong>the</strong> “mini clinical ethnography,” which sets out a brief anthropological<br />

assessment of <strong>the</strong> <strong>cultural</strong> <strong>factors</strong> that are immediately relevant<br />

to <strong>the</strong> clinical situation (19,20).<br />

In selecting a narrative model, <strong>the</strong> Group was consciously endorsing<br />

<strong>the</strong> growing importance of <strong>the</strong> study of narrative in anthropology<br />

and o<strong>the</strong>r social sciences, as well as echoing a tradition within mental<br />

health assessment: <strong>the</strong> psychodynamic <strong><strong>for</strong>mulation</strong> (14). In medicine<br />

in general, <strong>the</strong> use of narrative accounts of illness goes beyond diagnostic<br />

typologies to claim a different “truth” in <strong>the</strong> creation of a humanized<br />

account of suffering from <strong>the</strong> patient’s perspective that encompasses<br />

a greater view of <strong>the</strong> social world than <strong>the</strong> purely diagnostic<br />

evaluation (19). The use of this technique can also account <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> role<br />

that health institutions and practitioners have on <strong>the</strong> evolution of <strong>the</strong><br />

person’s illness and his/her perception and interpretation of it (21,22).<br />

This allows a reflexive stance on <strong>the</strong> clinician-patient interaction, in<br />

which <strong>the</strong> role of <strong>the</strong> practitioner in shaping <strong>the</strong> process of evaluation,<br />

including what is reported by <strong>the</strong> patient and what is perceived by <strong>the</strong><br />

clinician, can be “painted back in.”<br />

An outline of <strong>the</strong> Cultural Formulation was prepared and submitted<br />

to <strong>the</strong> DSM-IV Task Force. In addition, a field test was per<strong>for</strong>med on<br />

patients from four US ethnic minorities: African American, American<br />

Indian, Asian American, and Latino. The results revealed that <strong>the</strong> CF<br />

model could be successfully applied to patients from different <strong>cultural</strong><br />

backgrounds. An edited version of <strong>the</strong> proposed text was published in<br />

Appendix I of DSM-IV (15).<br />

As a result of its publication in DSM-IV, <strong>the</strong> Cultural Formulation<br />

has begun to <strong>for</strong>m part of <strong>the</strong> curricula of US psychiatry residency<br />

programs. Since 1996, <strong>the</strong> CF model has been <strong>the</strong> subject of a regular<br />

section on clinical case studies in Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry (14),<br />

of whom <strong>the</strong> senior author is <strong>the</strong> section editor, and of a yearly course at<br />

<strong>the</strong> Annual Meeting of <strong>the</strong> American Psychiatric Association. In 2001,<br />

<strong>the</strong> Cultural Psychiatry Committee of <strong>the</strong> Group <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> Advancement<br />

of Psychiatry published a book on <strong>the</strong> CF model that includes a number<br />

of case examples (12).<br />

CULTURAL FORMULATION OF A CLINICAL CASE<br />

The second part of this article summarizes a case study of an actual<br />

patient (23) that illustrates <strong>the</strong> purpose of each of <strong>the</strong> components<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Cultural Formulation and <strong>the</strong> impact on treatment outcome of

ROBERTO LEWIS-FERNÁNDEZ AND NAELYS DÍAZ 277<br />

implementing this model in clinical practice. In particular, <strong>the</strong> case<br />

highlights some of <strong>the</strong> diagnostic complexities involved in <strong>assessing</strong><br />

patients reporting nervios (nerves) and ataques de nervios (attacks of<br />

nerves), prevalent popular syndromes among Latinos. A brief summary<br />

of <strong>the</strong> clinical history is followed by <strong>the</strong> <strong>cultural</strong> <strong><strong>for</strong>mulation</strong> of <strong>the</strong> case.<br />

In<strong>for</strong>med consent was obtained from <strong>the</strong> patient <strong>for</strong> description of this<br />

clinical material.<br />

Clinical History<br />

A 49 year-old widowed Puerto Rican woman presented to an outpatient<br />

Latino Mental Health Clinic in New England after a 3-year history of<br />

prolonged hospitalizations due to recurrent major depressive disorder<br />

with diagnosed psychotic features and chronic impulsive suicidality.<br />

Except <strong>for</strong> brief periods of partial recovery lasting less <strong>the</strong>n 2 weeks,<br />

<strong>the</strong> patient reported several years of chronic sadness, anhedonia, tearfulness,<br />

psychomotor retardation, suicidality, guilty ruminations, decreased<br />

sleep and appetite, interest, energy, and concentration. She<br />

also suffered from restlessness, “nervousness,” trembling, increased<br />

startle, anguish, and severe headaches. Patient’s “psychotic” diagnosis<br />

was due to <strong>the</strong> following during her affective decompensations: hearing<br />

her name called when alone, glimpsing a darting shadow, and “feeling”<br />

someone behind her. Despite past traumas (physical abuse, husband’s<br />

murder) she denied many of <strong>the</strong> symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder.<br />

There was no history of substance abuse. Her first episode of<br />

major depression dated from age 32 and had recurred at least once<br />

be<strong>for</strong>e <strong>the</strong> current episode.<br />

Patient was born in rural Puerto Rico and had a 5th grade education.<br />

Her fa<strong>the</strong>r developed alcoholism while working as a seasonal agri<strong>cultural</strong><br />

migrant in <strong>the</strong> United States and was verbally abusive and physically<br />

threatening to <strong>the</strong> patient’s mo<strong>the</strong>r when intoxicated. The patient<br />

denied witnessing overt physical or sexual abuse or being <strong>the</strong> object<br />

of childhood trauma, but did complain of her mo<strong>the</strong>r’s cold distance.<br />

Patient married at 16 and had 6 children, one of whom died of pneumonia<br />

at 3 months of age. Husband also developed alcohol problems<br />

and became physically and emotionally abusive towards her. After an<br />

escalation of his abuse, patient ended <strong>the</strong> marriage by migrating to <strong>the</strong><br />

Eastern United States at age 31 with <strong>the</strong> man who became her second<br />

husband. She left four of her children behind with relatives, a decision<br />

that resulted in her parents’ rejection. Five years later she returned to<br />

Puerto Rico after <strong>the</strong> murder of her second husband in a street fight.<br />

The son who had migrated with her to <strong>the</strong> US entered a residential

278 PSYCHIATRIC QUARTERLY<br />

drug abuse program 11 years later, at which point she migrated to a<br />

different East Coast city at age 47 to be near her oldest son from whom<br />

she felt estranged. Her conflicts with this son and her o<strong>the</strong>r children<br />

precipitated her inpatient admissions.<br />

Inpatient psycho<strong>the</strong>rapy, antidepressants, and antipsychotics only<br />

produced minor improvement of her depression and suicidality and no<br />

change in her psychotic symptoms. After discharge to <strong>the</strong> outpatient<br />

Latino Clinic, her psychotic symptoms were reassessed as normative<br />

Puerto Rican spiritual expressions of demoralization and her molindone<br />

was discontinued. While still on phenelzine during evaluation <strong>for</strong> family<br />

<strong>the</strong>rapy, <strong>the</strong> patient suffered an ataque de nervios in <strong>the</strong> midst of an<br />

argument with her son. During <strong>the</strong> ataque, which was characterized by<br />

dissociative symptoms (depersonalization, “numbness”), she attempted<br />

an impulsive overdose with phenelzine. She required ICU treatment<br />

and a brief in-patient stay, and was taken off all psychiatric medications.<br />

Intensive psycho<strong>the</strong>rapeutic management was instituted, initially including<br />

individual, family, and group modalities. Improved family relations<br />

resulted in marked decrease in symptoms. Outpatient assessment<br />

and psycho<strong>the</strong>rapy revealed patient’s longstanding characterological<br />

symptoms and she received a diagnosis of Borderline Personality Disorder.<br />

She reduced her participation in treatment after a few months,<br />

preferring weekly supportive psycho<strong>the</strong>rapy and monthly psychiatric<br />

visits. These latter acted as a kind of supervision of her clinical picture,<br />

since medications were not prescribed. Patient was followed off<br />

medications <strong>for</strong> 8 years without recurrence of major depression or suicidality.<br />

She did develop periodic exacerbations of depressive, anxiety,<br />

dissociative, and somatization symptoms that did not meet specified diagnostic<br />

criteria. Though she continued to perceive “shadows” and hear<br />

her name called when alone, <strong>the</strong>se experiences produced only temporary<br />

concern. There was never any evidence of <strong>for</strong>mal thought disorder<br />

nor loss of generalized reality orientation [Summarized from (23)].<br />

Cultural Formulation<br />

Cultural Identity<br />

The section on Cultural Identity serves as an introduction to <strong>the</strong> rest of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Cultural Formulation. Its purpose is to identify <strong>for</strong> each patient <strong>the</strong><br />

particular mix of socio-<strong>cultural</strong> influences that has patterned his/her<br />

individual <strong>cultural</strong> world. As stated earlier, cultures are experienced<br />

differently by different members according to subgroup characteristics<br />

such as gender, class, religion, race, and sexual orientation, among

ROBERTO LEWIS-FERNÁNDEZ AND NAELYS DÍAZ 279<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>factors</strong>. This section of <strong>the</strong> <strong><strong>for</strong>mulation</strong> collects in<strong>for</strong>mation on<br />

how <strong>the</strong>se various social <strong>factors</strong> impact <strong>the</strong> person’s <strong>cultural</strong> environment<br />

in order to prevent overly general or stereotypical interpretations<br />

of <strong>cultural</strong> influence (13). This section also permits assessment of <strong>the</strong><br />

person’s own sense of his/her ethno-<strong>cultural</strong> identity, particularly in<br />

respect to o<strong>the</strong>r alternative identities; this takes on particular significance<br />

in settings of rapid <strong>cultural</strong> change or ethnic conflict, or among<br />

migrants or persons of multi<strong>cultural</strong> heritage. At <strong>the</strong> conclusion of this<br />

section, <strong>the</strong> <strong><strong>for</strong>mulation</strong> writer should have a sense of how <strong>the</strong> person<br />

fits against a specific <strong>cultural</strong> background. This serves as a prelude to<br />

understanding how his/her individual experience of <strong>the</strong> illness and its<br />

meanings and outcomes fit within that <strong>cultural</strong> context, which is <strong>the</strong><br />

topic of <strong>the</strong> rest of <strong>the</strong> CF model (12).<br />

The following subsections are included within <strong>the</strong> general section on<br />

Cultural Identity. For <strong>the</strong> purpose of illustrating its content, each subsection<br />

begins with one key question regarding <strong>the</strong> case under discussion<br />

that summarizes <strong>the</strong> subsection topic. We will follow this <strong>for</strong>mat<br />

<strong>for</strong> every subsection throughout <strong>the</strong> article.<br />

Reference Group. Within her overall group (Puerto Rican culture),<br />

which particular <strong>cultural</strong> subgroups <strong>for</strong>m <strong>the</strong> relevant context <strong>for</strong> <strong>assessing</strong><br />

this person?<br />

A key influence on this patient’s <strong>cultural</strong> background is her status<br />

as a rural person with limited <strong>for</strong>mal education who migrated twice<br />

to <strong>the</strong> US <strong>for</strong> a total of 13 years’ residence as part of <strong>the</strong> “circular”<br />

pattern of Puerto Rican migration that intensified in <strong>the</strong> 1960’s and<br />

70’s. The “circularity” of this migratory stream consists of recurrent<br />

“back and <strong>for</strong>th” moves between Puerto Rico and usually <strong>the</strong> East Coast<br />

of <strong>the</strong> United States in search of better economic and health care opportunities<br />

and in order to reestablish family and <strong>cultural</strong> links (24).<br />

Like many of <strong>the</strong>se migrants, she was only mildly acculturated despite<br />

this extended stay, given her periodic returns to her culture of origin<br />

and <strong>the</strong> barriers to integration into <strong>the</strong> US mainstream <strong>for</strong> persons<br />

of her ethnic, class, and educational background caused by chronic<br />

unemployment and limited housing options outside of encapsulated<br />

Latino neighborhoods (25). Her self-identity remained that of an Island<br />

Puerto Rican, despite her migratory experience. In effect, this<br />

patient had retained most of <strong>the</strong> traditional views of illness from her<br />

rural background despite several years of residence in US urban<br />

settings.<br />

In this subsection it is also important to understand <strong>the</strong> patient’s migratory<br />

process in <strong>the</strong> context of her <strong>for</strong>mer experience in Puerto Rico

280 PSYCHIATRIC QUARTERLY<br />

and <strong>the</strong> reasons <strong>for</strong> her migration (13). Because her initial migration occurred<br />

in order to escape her husband’s physical abuse, and involved a<br />

prolonged separation from her children, this person’s migratory process<br />

is akin in some respects to that of a refugee, an unusual status among<br />

low-income Puerto Rican migrants, who are usually motivated by economic<br />

reasons. Some of her subsequent psychiatric symptoms, such as<br />

her acute alienation, guilt, and suicidality, can be better understood<br />

against this unusual migratory context.<br />

Language. Does <strong>the</strong> patient have access to more than one language<br />

<strong>for</strong> expressing her illness-related experiences and obtaining care, and if<br />

so, which language predominates?<br />

Language assessment is an important element of <strong>the</strong> CF model because<br />

language identifies and codifies a person’s experience, which can<br />

be distorted in <strong>the</strong> process of translation. In <strong>the</strong> case of multilingual<br />

individuals, <strong>the</strong> use of a secondary language may limit <strong>the</strong> ability to obtain<br />

an accurate history and reach a valid diagnosis, since emotionality<br />

and cognition may be expressed differently in different languages. For<br />

example, an individual may appear more or less pathological depending<br />

on <strong>the</strong> language of <strong>the</strong> evaluation (26).<br />

This patient used Spanish predominantly in all her daily interactions.<br />

Her use of English was very rare and her fluency poor. This constitutes<br />

ano<strong>the</strong>r sign of her limited participation in non-Latino US society.<br />

Although <strong>the</strong> in-patient unit employed interpreters regularly in <strong>the</strong><br />

care of <strong>the</strong> patient, it is likely that some of <strong>the</strong> limitations in <strong>the</strong>ir clinical<br />

assessment were related to difficulties in bridging <strong>the</strong> language gap,<br />

resulting in relatively shallow interpretations of her experience. For example,<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>cultural</strong> connotations <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> Spanish terms that <strong>the</strong> patient<br />

used to express her distress, such as nervios (nerves), ataques (attacks),<br />

and celajes (glimpses or shadows, understood by <strong>the</strong> staff as visual hallucinations),<br />

appear to have been lost or distorted during <strong>the</strong> translation<br />

process.<br />

Cultural Factors in Development. Are <strong>the</strong>re features of <strong>the</strong> patient’s<br />

childhood development that should be placed in a specific <strong>cultural</strong> context<br />

in order to be properly understood?<br />

Locating childhood development within a <strong>cultural</strong> context can help<br />

clarify <strong>the</strong> contribution of environmental <strong>factors</strong> to personality characteristics<br />

(12). Experience is made meaningful and incorporated as enduring<br />

personal attributes partly in response to its perceived normality<br />

and collective interpretation. Factors that influence personality development<br />

and that vary across cultures include, among o<strong>the</strong>rs: gender

ROBERTO LEWIS-FERNÁNDEZ AND NAELYS DÍAZ 281<br />

roles, relational characteristics within <strong>the</strong> family and roles within <strong>the</strong><br />

family constellation, socialization experiences, and social valuation of<br />

emotional expression (27,28).<br />

In this case, <strong>the</strong> patient’s childhood contacts were limited to her extended<br />

kin group, given <strong>the</strong> rural isolation of her family compound and<br />

her early school termination. This may have intensified <strong>the</strong> negative<br />

impact on her personality development of her fa<strong>the</strong>r’s disruptive and<br />

abusive behavior and her mo<strong>the</strong>r’s affective distance despite <strong>the</strong> stated<br />

absence of witnessed or experienced physical or sexual abuse during<br />

childhood. These personality patterns were probably also rein<strong>for</strong>ced<br />

by later adult episodes of physical abuse and traumatic loss. Ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

socio<strong>cultural</strong> feature of <strong>the</strong> patient’s early socialization that appears<br />

to have influenced her later symptomatology relates to her role as a<br />

parentified child who was removed from elementary school in order to<br />

help raise her younger siblings. Though not an uncommon practice in<br />

<strong>the</strong> patient’s <strong>cultural</strong> reference group, this seems to have determined a<br />

particularly important element in her self-perception, as evidenced by<br />

her lifelong nickname within <strong>the</strong> family which refers to this maternal<br />

function. The loss of this <strong>cultural</strong>ly established role, through separation<br />

and subsequent estrangement from her children, was <strong>the</strong> main<br />

cause of <strong>the</strong> patient’s affective decompensation. The partial resumption<br />

of this role through family <strong>the</strong>rapy marked <strong>the</strong> beginning of her<br />

improvement.<br />

Involvement with Culture of Origin and Host Culture. How does understanding<br />

a migrant like this patient in <strong>the</strong> context of her culture of<br />

origin separately from <strong>the</strong> host culture reveal something about her as a<br />

person and about her migration experience?<br />

This subsection is primarily relevant to migrants. Its purpose is to<br />

compare <strong>the</strong> individual’s involvement with <strong>the</strong> culture of origin, on <strong>the</strong><br />

one hand, to his/her involvement with <strong>the</strong> host culture, on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r.<br />

By evaluating each attachment independently, <strong>the</strong> clinician can avoid<br />

a zero-sum model of acculturation, which mistakenly assumes that as<br />

a person becomes more fluent in <strong>the</strong> new culture, he/she necessarily<br />

becomes disconnected from his/her culture of origin (29). Instead, contemporary<br />

acculturation models understand that, in a world where multi<strong>cultural</strong>ity<br />

and geographical displacement are becoming increasingly<br />

prevalent, multiple combinations of involvement are possible, such as<br />

<strong>the</strong> alternative of developing a deep connection to both <strong>cultural</strong> environments<br />

(30). Finally, by establishing <strong>the</strong> migrant’s relative <strong>cultural</strong><br />

attachments, <strong>the</strong> person’s <strong>cultural</strong> identity is rounded out, setting <strong>the</strong><br />

stage <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r topics of <strong>the</strong> CF model.

282 PSYCHIATRIC QUARTERLY<br />

This patient was predominantly connected to her culture of origin<br />

and had limited contact with <strong>the</strong> host culture. She lived in a mainly<br />

Latino neighborhood and traveled frequently to Puerto Rico, where<br />

she kept in close contact with several siblings; she had few friends,<br />

mostly Latinas, apart from her family. She was, however, able to maneuver<br />

some aspects of United States urban life well, such as obtaining<br />

elderly subsidized housing (though only in her 50’s) and disability<br />

benefits.<br />

Cultural Explanations of <strong>the</strong> Illness<br />

The heart of <strong>the</strong> Cultural Formulation is this second section, which<br />

examines <strong>the</strong> <strong>cultural</strong> <strong>factors</strong> that affect <strong>the</strong> experience and interpretation<br />

of illness, as understood by <strong>the</strong> patient, <strong>the</strong> family, and <strong>the</strong> social<br />

network. These <strong>cultural</strong> <strong>factors</strong> exert a deeper influence than just covering<br />

over an unchanging reality with curious <strong>cultural</strong> explanations.<br />

They instead help to create <strong>the</strong> illness experience by affecting cognitive,<br />

bodily, and interpersonal aspects of disease, including by helping<br />

to shape symptom presentations, perceived etiologies, severity attributions,<br />

treatment choices, and outcome expectations (6,31). In particular,<br />

explicit <strong>cultural</strong> analysis is required <strong>for</strong> accurate assessment of<br />

<strong>the</strong> severity of <strong>the</strong> presenting problems, since patients’ attributions of<br />

severity are acutely impacted by <strong>cultural</strong> interpretations. Finally, adherence<br />

to clinicians’ recommendations may be compromised without<br />

careful attention to patients’ <strong>cultural</strong> views of treatment. In this respect,<br />

it may also be necessary to account <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> views of key relatives<br />

or members of <strong>the</strong> larger social network (32).<br />

Idioms of Distress and Local Illness Categories. How do <strong>cultural</strong> <strong>factors</strong><br />

affect <strong>the</strong> way this person experiences and understands her distress,<br />

including <strong>the</strong> specific shape of <strong>the</strong> presenting symptoms and <strong>the</strong> way<br />

<strong>the</strong>y are clustered?<br />

Cross-<strong>cultural</strong> research reveals <strong>the</strong> existence of multiple overall perspectives<br />

on distress—ways in which to experience, understand, and<br />

describe it—that are so comprehensive that <strong>the</strong>y seem akin to different<br />

languages of suffering ra<strong>the</strong>r than specific syndromes. The term<br />

“idioms of distress” is used to denote <strong>the</strong>se different languages of experience<br />

(33). Examples of idioms are: <strong>the</strong> tendency to somatize suffering,<br />

or to psychologize it; experiencing interpersonal problems or physical<br />

illness as <strong>for</strong>ms of possession; attributing illness to <strong>the</strong> impact of suffering<br />

on <strong>the</strong> anatomical “nerves”; or describing distress in terms of “fate,”<br />

or as a kind of “spiritual test” (16).

ROBERTO LEWIS-FERNÁNDEZ AND NAELYS DÍAZ 283<br />

In addition to <strong>the</strong>se general <strong>for</strong>ms, cultures have also evolved more<br />

specific illness categories or syndromes, assembled according to alternative<br />

systems of causation. The organizing principle can be a relatively<br />

invariant collections of symptoms, a perceived common etiology,<br />

or a shared response to treatment (5). One of <strong>the</strong> essential tasks of a<br />

Cultural Formulation is to discover <strong>the</strong> idioms of distress and <strong>the</strong> illness<br />

categories that are evoked by <strong>the</strong> patient’s presentation. Often<br />

<strong>the</strong> patient is not fully conscious of <strong>the</strong> categories he/she is referencing,<br />

and yet may be acutely aware of <strong>the</strong> dissonance between his/her<br />

understandings and those of <strong>the</strong> clinician.<br />

In this case, <strong>the</strong> patient’s illness was described by herself and her community<br />

as nervios (nerves) and ataques de nervios (attacks of nerves).<br />

Patient’s view of her nervios was typical of many traditional Puerto<br />

Ricans, <strong>for</strong> whom it is an idiom of distress describing a vulnerability to<br />

experiencing symptoms of depression, anxiety, dissociation, somatization<br />

and rarely psychosis or poor impulse control given interpersonal<br />

frustrations (34). The idiom is held toge<strong>the</strong>r conceptually by <strong>the</strong> <strong>cultural</strong><br />

understanding that all its presentations reflect an “alteration,”<br />

acquired or inherited, of <strong>the</strong> nervous system, and specifically of <strong>the</strong><br />

anatomical nerves. The patient had suffered from all <strong>the</strong> symptoms<br />

of nervios except psychosis. Her acute fit-like exacerbations of nervios<br />

are known as ataques de nervios, and were characterized by paroxysms<br />

of anxiety, rage, dissociation, and impulsive suicidality followed<br />

by depression and exhaustion in response to acute interpersonal conflicts<br />

(9,11). In this patient’s case, nervios and ataques were associated<br />

with her character pathology, but many Puerto Ricans suffer from similar<br />

folk syndromes without showing characterological deficits, though<br />

<strong>the</strong> exact relationship between <strong>the</strong>se clinical conditions has not been<br />

ascertained.<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r critical aspect of her nervios was <strong>the</strong> high frequency and<br />

distressing nature of <strong>the</strong> <strong>cultural</strong>ly specific perceptual distortions she<br />

reported (hearing voices, feeling presences, seeing shadows [known as<br />

celajes; glimpses]). These experiences are very prevalent among Puerto<br />

Ricans with and without nervios, but sufferers of ataques are markedly<br />

more distressed by <strong>the</strong>m (35). They probably represent <strong>cultural</strong>ly patterned<br />

signs of anxiety or emotional distress determined by a person’s<br />

dissociative capacity. In <strong>the</strong> patient’s case, <strong>the</strong>se experiences were mistaken<br />

<strong>for</strong> psychotic symptoms by her inpatient clinicians. As such, discussion<br />

of <strong>the</strong>se symptoms in <strong>the</strong> Cultural Formulation straddles this<br />

subsection and <strong>the</strong> next, as <strong>the</strong>y constitute <strong>cultural</strong>ly specific idioms of<br />

distress whose interpretation can affect <strong>the</strong> perceived severity of <strong>the</strong><br />

presenting complaints.

284 PSYCHIATRIC QUARTERLY<br />

Meaning and Severity of Symptoms in Relation to Cultural Norms.<br />

How does taking her <strong>cultural</strong> background into account affect <strong>the</strong> level<br />

of pathology suggested by her presenting symptoms and <strong>the</strong>ir meaning<br />

as a <strong>for</strong>m of communication in her interpersonal context?<br />

This subsection is devoted to a careful assessment of <strong>the</strong> level of<br />

severity implied by <strong>the</strong> person’s symptoms, as well as to discussion of<br />

<strong>the</strong> role of <strong>the</strong> illness as a <strong>for</strong>m of interpersonal communication that is<br />

interpreted by o<strong>the</strong>rs in <strong>the</strong> social network. It is essential that <strong>cultural</strong><br />

norms be considered when <strong>assessing</strong> <strong>the</strong> clinical severity of specific behaviors,<br />

so as to avoid two erroneous extremes: overpathologizing what<br />

is normative in a <strong>cultural</strong> group, or ascribing to normal behavior what is<br />

considered pathological in that culture (13,36). Whe<strong>the</strong>r what is at issue<br />

is <strong>the</strong> normal degree of individuation of an 18 year-old in relation to<br />

his/her parents, or <strong>the</strong> potential delusionality of a person who ascribes<br />

his/her symptoms to a supernatural etiology, some knowledge of local<br />

behavioral norms is essential to <strong>the</strong> process of diagnosis. The fact that<br />

different subgroups within a larger <strong>cultural</strong> setting may interpret <strong>the</strong>se<br />

behaviors differently complicates <strong>the</strong> process of assessment and <strong>for</strong>ces<br />

an individualized evaluation of <strong>cultural</strong> <strong>factors</strong> in each case.<br />

In addition, illness expressions convey a range of meanings to o<strong>the</strong>rs<br />

in <strong>the</strong> social network. Which set of meanings is imputed by <strong>the</strong> community<br />

actually has an impact on <strong>the</strong> patient’s course, both through interpersonal<br />

interactions that promote improvement or pathology and<br />

through concrete levels of assistance or rejection. The cross-<strong>cultural</strong><br />

literature on <strong>the</strong> contribution of expressed emotion to <strong>the</strong> course of<br />

schizophrenia represents a well-developed example of this issue (37).<br />

In this patient’s case, her symptoms at <strong>the</strong> time of presentation were<br />

seen by her community to reflect a severe <strong>for</strong>m of nervios because <strong>the</strong>y<br />

could precipitate rage and dissociation ataques with impulsive suicidality<br />

and because <strong>the</strong>y had “penetrated deeply,” causing her character<br />

pathology. As opposed to her outpatient clinicians, who saw her character<br />

problems as preceding and partly determining her Axis I disorders,<br />

<strong>the</strong> patient’s social network understood her characterological symptoms<br />

as a consequence of her nervios, ra<strong>the</strong>r than as a cause (i.e., a <strong>for</strong>m of<br />

bitterness due to her continued suffering), and thus as a sign of nervios<br />

severity. In ano<strong>the</strong>r discrepancy between <strong>the</strong> social network and <strong>the</strong><br />

clinical team, <strong>the</strong> patient’s inpatient clinicians judged her perceptual<br />

distortions to be much more severe than her community, understanding<br />

<strong>the</strong>m as signs of psychosis ra<strong>the</strong>r than minor elements of her overall<br />

condition.<br />

Fur<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong> expectation of her interpersonal network was that <strong>the</strong><br />

patient actively ward against any worsening of her character pathology

ROBERTO LEWIS-FERNÁNDEZ AND NAELYS DÍAZ 285<br />

by “controlling” her needs and desires and focusing on <strong>the</strong> needs of<br />

o<strong>the</strong>rs, such as her children. The community thus validated <strong>the</strong> patient’s<br />

understanding that reestablishing positive affective links with<br />

her family would improve <strong>the</strong> outcome of her nervios. Her achievement<br />

of this goal, as well as her coming off psychiatric medications and preventing<br />

fur<strong>the</strong>r ataques, were considered signs of improvement. The<br />

patient’s children, however, initially rejected <strong>the</strong> patient’s and <strong>the</strong> community’s<br />

understanding that her character pathology stemmed from<br />

her nervios and ataques, attributing it instead to manipulative ploys<br />

aimed at deflecting <strong>the</strong>ir justified anger due to what <strong>the</strong>y perceived as<br />

her neglectful parenting. Therapy helped to bridge <strong>the</strong>se conflicting interpretations,<br />

but several of her children always retained <strong>the</strong> sense that<br />

<strong>the</strong> patient’s personality conflicts exceeded <strong>the</strong> norm even <strong>for</strong> nervios.<br />

Perceived Causes and Explanatory Models. How is her clinical management<br />

affected by knowing about her <strong>cultural</strong>ly based etiological<br />

attributions, her understandings of pathophysiology, and her hopes and<br />

concerns about <strong>the</strong> course of <strong>the</strong> illness?<br />

This subsection focuses on <strong>the</strong> patient’s views on how <strong>the</strong> illness<br />

“works”: what caused it; why did it present now and in this way; how is it<br />

affecting <strong>the</strong> person; what would happen if it was not treated; and what<br />

are <strong>the</strong> possible outcomes even with treatment? (12,38). This subsection,<br />

like <strong>the</strong> next one on help-seeking to which it is closely linked, is especially<br />

important during <strong>the</strong> process of enlisting <strong>the</strong> patient’s and <strong>the</strong><br />

family’s adherence to <strong>the</strong> clinician’s recommendations. Patients rarely<br />

pursue treatments <strong>for</strong> long that run counter to <strong>the</strong>ir primary etiological<br />

understandings. Cultural attributions of causation actually vary widely<br />

across societies, from biological to spiritual etiologies, and from drastically<br />

individual, internal views to social and even cosmological interpretations<br />

(39). Often, <strong>the</strong>re are a mix of attributions, at times partly<br />

or wholly contradictory within one person or across <strong>the</strong> patient’s social<br />

network. Treatment may thus involve negotiating <strong>the</strong> appearance<br />

of <strong>the</strong>se various perspectives and bringing <strong>the</strong>m into some coherent<br />

strategy (19).<br />

At first, <strong>the</strong> patient saw her condition fundamentally as a medical<br />

problem caused by an “alteration” of her nervous system due to <strong>the</strong><br />

suffering produced by chronically unresolved family conflicts. Primary<br />

among <strong>the</strong>se were <strong>the</strong> physical abuse by her husband, <strong>the</strong> parental<br />

rejection, and her separation from several of her children during most<br />

of <strong>the</strong>ir childhood, which led to <strong>the</strong>ir ongoing anger toward her. This is a<br />

typical traditional Puerto Rican interpretation of <strong>the</strong> impact of chronic<br />

suffering on <strong>the</strong> “nerves.” If untreated, <strong>the</strong> patient feared that she would

286 PSYCHIATRIC QUARTERLY<br />

become chronically psychotic (“loca”; crazy), given her limited ability, by<br />

herself, to “control” her symptoms, particularly her anger and grief (40).<br />

Over time, however, medical treatment without family reconciliation<br />

was likewise experienced as insufficient. The traditional link between<br />

nervous ailments and past stressors served <strong>the</strong> outpatient clinicians as<br />

an entry point <strong>for</strong> discussing her interpersonal history, including <strong>the</strong><br />

conflict with her children. One important function of her caregivers became<br />

that of contributing medical authority to <strong>the</strong> patient’s claims <strong>for</strong><br />

filial support. In that sense, <strong>the</strong> interpersonal element in her system<br />

of etiological attributions grew to supersede <strong>the</strong> more physiological aspects<br />

of her explanatory model. Her ongoing participation in treatment<br />

was attained in large measure by <strong>the</strong> growing confluence of this model<br />

with that of her providers, who also saw her problematic family relationships<br />

as a main cause of her illness. In fact, clinicians’ success in enlisting<br />

family support <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> patient became proof of <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>the</strong>rapeutic<br />

value.<br />

A secondary element of her explanatory model was <strong>the</strong> notion that<br />

her nervios illness produced a kind of spiritual “weakness,” which led to<br />

<strong>the</strong> irruption of distressing spiritual visitations, perhaps by deceased<br />

relatives, which were experienced as perceptual distortions. This aspect<br />

of her model was never primary nor fully worked out, yet it initially<br />

disrupted her care, as it led to a diagnosis of psychosis by <strong>the</strong> inpatient<br />

team. Even when improved, however, <strong>the</strong> patient remained leery of<br />

<strong>the</strong>se experiences, preferring to pay <strong>the</strong>m minimal attention.<br />

Help-Seeking Experiences and Plans. How does <strong>the</strong> patient’s <strong>cultural</strong><br />

identity help explain her past help-seeking choices and expectations<br />

about current and future <strong>for</strong>ms of assistance and treatment?<br />

This subsection is closely linked to <strong>the</strong> previous one, as individuals<br />

usually seek out caregivers who offer assistance in ways that match<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir explanatory models (13,19). Patients’ help-seeking choices actually<br />

tend to follow “pathways” of care which are partly determined<br />

by psychosocial and <strong>cultural</strong> <strong>for</strong>ces. One expression of this is <strong>the</strong> way<br />

<strong>cultural</strong> perceptions and interpretations of illness affect not only <strong>the</strong><br />

decision whe<strong>the</strong>r and when to seek <strong>for</strong>mal care (as opposed to being<br />

self-reliant or asking <strong>for</strong> help from <strong>the</strong> immediate social network), but<br />

also <strong>the</strong> type of treatment that is considered to be adequate and effective<br />

(41). As with etiological attributions, help-seeking pathways can<br />

also be quite complex, with multiple <strong>for</strong>ms of care being accessed at<br />

once, or in apparently contradictory ways.<br />

During her early bouts of depression, which were acute but brief and<br />

occurred years be<strong>for</strong>e <strong>the</strong> current presentation, <strong>the</strong> patient did not seek

ROBERTO LEWIS-FERNÁNDEZ AND NAELYS DÍAZ 287<br />

ongoing medical care, relying only on rare emergency room visits. At<br />

<strong>the</strong> time, she felt her life traumas had not yet permanently “altered” her<br />

nervous system, and she relied mostly on her limited social network and<br />

on home remedies, such as herbal teas. Early on during her current presentation,<br />

however, having come to see her condition as a physiological<br />

reaction to her interpersonal problems, she sought help first from primary<br />

care internists. They in turn referred her to inpatient psychiatric<br />

care, which <strong>the</strong> patient always understood as being sent to <strong>the</strong> medical<br />

specialists of <strong>the</strong> nervous system (“<strong>the</strong> doctors <strong>for</strong> nervios”). This was<br />

a <strong>for</strong>tunate reframing of her treatment, since an alternative and fairly<br />

common interpretation in her <strong>cultural</strong> group could have been to reject<br />

<strong>the</strong> psychiatric referral as a sign that <strong>the</strong> clinicians mistakenly thought<br />

that she was losing her mind. Over time, she accepted some <strong>for</strong>ms of<br />

mental health treatment but refused o<strong>the</strong>rs, due to a mixture of <strong>cultural</strong><br />

and personality characteristics. Family <strong>the</strong>rapy, <strong>for</strong> example, met<br />

her view that an improved relationship with her son would help her recover<br />

from her illness, and was enthusiastically accepted. O<strong>the</strong>r <strong>for</strong>ms<br />

of psycho<strong>the</strong>rapy directed more at intrapsychic change, such as group<br />

<strong>the</strong>rapy, met intense resistance. Day hospital care came to be experienced<br />

as relatively unfocused and off-<strong>the</strong>-mark; instead, patient sought<br />

daily visits with her daughter-in-law, where she could re-establish socialization<br />

skills with family members. Her view of nervios as a medical<br />

condition never fully disappeared. She felt best protected from relapse<br />

by periodic check-ups with a psychiatrist, even when no medications<br />

were prescribed; <strong>the</strong> ongoing decision not to medicate reassured her<br />

that her condition remained stable. Interestingly, despite <strong>the</strong> view that<br />

her perceptual distortions were due to spiritual “weakness,” she never<br />

sought <strong>the</strong> help of folk healers, saying “I don’t believe in any of that.”<br />

This highlights <strong>the</strong> intra-ethnic variation in help-seeking pathways,<br />

since many Puerto Ricans seek <strong>the</strong> assistance of espiritistas and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

spiritual healers at some point during <strong>the</strong> course of <strong>the</strong>ir illness (42).<br />

Cultural Factors Related to Psychosocial Environment<br />

and Levels of Functioning<br />

This section of <strong>the</strong> CF model allows <strong>the</strong> clinician to examine how culture<br />

patterns some of <strong>the</strong> stressors patients are exposed to and <strong>the</strong>ir reactions<br />

to <strong>the</strong>se situations; <strong>the</strong> social supports available to <strong>the</strong>m; and <strong>the</strong><br />

contexts against which <strong>the</strong>ir levels of functioning should be measured.<br />

Among o<strong>the</strong>r stressors, this part of <strong>the</strong> assessment can be used to elicit<br />

patients’ experiences of trauma and how <strong>the</strong>y incorporate <strong>the</strong>se events<br />

into <strong>the</strong>ir ongoing interpersonal relationships.

288 PSYCHIATRIC QUARTERLY<br />

Social Stressors. How does <strong>the</strong> patient’s <strong>cultural</strong> background clarify<br />

<strong>the</strong> origin and impact of <strong>the</strong> stressors she experienced?<br />

The main stressor affecting <strong>the</strong> patient at <strong>the</strong> time of her presentation<br />

was her estrangement from all of her children, which contradicts traditional<br />

values regarding an extended and close family centered around<br />

a matriarch. The patient alternated between feeling that this situation<br />

was unfair and that it was a deserved punishment <strong>for</strong> abandoning four<br />

of her children in childhood. That decision, which she described as <strong>the</strong><br />

hardest of her life, was influenced by several social and <strong>cultural</strong> <strong>factors</strong>.<br />

These include: <strong>the</strong> existence at that time of very few nonfamily<br />

supports <strong>for</strong> abused women in rural Puerto Rico; <strong>the</strong> emergence of migration<br />

as a government-sponsored escape valve <strong>for</strong> a labor <strong>for</strong>ce made<br />

redundant by rapid industrialization; her parents’ lack of support <strong>for</strong><br />

marital separation, even in <strong>the</strong> case of physical abuse; a tradition in<br />

rural Puerto Rico of placing “extra” children in in<strong>for</strong>mal foster arrangements<br />

with close relatives; and <strong>the</strong> expectation by some new male sexual<br />

partners (<strong>the</strong> man who became <strong>the</strong> patient’s second husband) that<br />

<strong>the</strong>y not be expected to maintain non-infant children from a previous<br />

marriage.<br />

Seen over <strong>the</strong> course of her lifetime, <strong>the</strong> patient’s stressors were severe,<br />

and included <strong>the</strong> family disruption caused by her fa<strong>the</strong>r’s alcoholism,<br />

her husband’s physical abuse, <strong>the</strong> death of a child in infancy,<br />

<strong>the</strong> dispersion of her nuclear family and <strong>the</strong> consequent discord with<br />

her parents and children, difficulties in acculturation to <strong>the</strong> US, ethnic<br />

discrimination, chronic poverty and unemployment, <strong>the</strong> murder of<br />

her second husband, and her children’s substance abuse and subsequent<br />

loss of child custody. These stressors were considered by <strong>the</strong> patient<br />

and her community to be adequate explanation of her nervios<br />

illness.<br />

Social Supports. How does her <strong>cultural</strong> identity contribute to <strong>the</strong><br />

amount, nature, and quality of her social supports?<br />

As a “circular” migrant who engaged in several migratory cycles and<br />

frequent trips to Puerto Rico, <strong>the</strong> patient’s supports beyond her son,<br />

daughter-in-law, and caregivers consisted only of community drop-in<br />

centers and a few elderly Latinas. Her lack of supports probably contributed<br />

to <strong>the</strong> length of her hospitalizations, as her fear of going home<br />

seemed to worsen her suicidality whenever discharge was discussed.<br />

Clinicians’ ef<strong>for</strong>ts to expand her support system through group <strong>the</strong>rapy<br />

membership and psychiatric social clubs were hindered by her<br />

character pathology. Most of <strong>the</strong> patient’s symptoms, including her suicidal<br />

ataques, may be understood as attempts to expand her social

ROBERTO LEWIS-FERNÁNDEZ AND NAELYS DÍAZ 289<br />

support network by engaging <strong>the</strong> attention of family members as well<br />

as professional caregivers. The patient always retained <strong>the</strong> belief that<br />

in <strong>the</strong> face of her overwhelming social limitations and <strong>the</strong> original recalcitrance<br />

of her children, only <strong>the</strong> full expression of her symptomatology<br />

could have produced a positive outcome.<br />

Levels of Functioning and Disability. How does <strong>the</strong> patient’s <strong>cultural</strong><br />

environment affect her level of functioning and degree of impairment?<br />

Prior to her improvement, <strong>the</strong> patient saw her illness as progressive<br />

and without cure, and feared degeneration into permanent insanity,<br />

consistent with widespread <strong>cultural</strong> concerns about severe nervios. As<br />

a result of treatment, she came to feel that her nervios had not progressed<br />

as far as she had feared, but that she would always remain<br />

permanently vulnerable to relapse if confronted with more stress than<br />

she could handle, especially in her family interactions. She interpreted<br />

<strong>the</strong> intermittent appearance of anxiety and depressive symptoms as<br />

signs of ongoing nervios illness which entitled her to lifelong subsidized<br />

housing and financial support from <strong>the</strong> government. Her age and<br />

limited <strong>for</strong>mal education, job skills, and English fluency in any case<br />

narrowed her employment opportunities considerably and contributed<br />

to her expectation of government support. Un<strong>for</strong>tunately, <strong>the</strong> absence<br />

of organized activities such as work also hindered <strong>the</strong> development<br />

of a social network beyond her family, which may have helped to decompress<br />

<strong>the</strong> patient’s dependence on a limited number of supportive<br />

contacts.<br />

Cultural Elements of <strong>the</strong> Clinician–Patient Relationship<br />

This section allows <strong>the</strong> clinician to consider how his/her own role or<br />

institutional setting has affected <strong>the</strong> patient’s illness experience, including<br />

symptom expression and treatment response. The scientific<br />

emphases on objectivity and material reality sometimes cause psychiatrists<br />

to mistake <strong>the</strong>ir activity <strong>for</strong> that of invisible observers, who exert<br />

little effect on <strong>the</strong> situation observed. On <strong>the</strong> contrary, much clinical<br />

and ethnographic research has described how patients’ symptom descriptions<br />

and etiological attributions are shaped across health care<br />

settings in response to clinicians’ verbal and nonverbal elicitations and<br />

to individual and collective expectations of what <strong>the</strong> purpose and <strong>the</strong><br />

norms are <strong>for</strong> each kind of setting (38,43). What counts as good and<br />

bad outcomes also varies across <strong>the</strong>rapeutic interactions, depending<br />

on whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> patient and caregiver are focusing on symptoms, longterm<br />

morbidity and mortality, psychosocial functioning, interpersonal

290 PSYCHIATRIC QUARTERLY<br />

relationships, existential adjustment, ecological integration, or spiritual<br />

well-being. The clinical encounter is always a negotiated experience<br />

(44) that in addition echoes a wider system of institutional relationships,<br />

such as <strong>the</strong> organization of health care services, <strong>the</strong> influence of<br />

third-party review, and pressures brought to bear by employers (22).<br />

The clinical relationship is also impacted by ethno-<strong>cultural</strong> clashes in<br />

<strong>the</strong> society at large, requiring clinicians to examine <strong>the</strong>ir attitudes toward<br />

a patient’s ethnicity and culture and how <strong>the</strong>se impact <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>rapeutic<br />

encounter. This understanding can be helpful not only in terms<br />

of evaluating <strong>the</strong> role of <strong>cultural</strong> differences in <strong>the</strong> interpretation of<br />

patients’ presentations, but also in avoiding biases based on ethnic<br />

stereotypes or o<strong>the</strong>r aspects of <strong>cultural</strong> identity (13). The current section<br />

encourages a systematic reflection on <strong>the</strong>se interactions.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> case of this patient, her psychiatric care prior to her referral<br />

to <strong>the</strong> outpatient Latino Clinic was hindered by <strong>the</strong> inpatient unit’s<br />

lack of <strong>cultural</strong> in<strong>for</strong>mation on various aspects of her presentation that<br />

have been outlined in this Formulation. In particular, <strong>the</strong> diagnostic<br />

process was limited by <strong>the</strong> absence of a <strong>cultural</strong>ly normative assessment<br />

of <strong>the</strong> patient’s character structure, which resulted in <strong>the</strong> overemphasis<br />

of her Axis I symptoms and a missed diagnosis of Borderline<br />

Personality Disorder. Likewise, lack of in<strong>for</strong>mation about <strong>the</strong> <strong>cultural</strong><br />

characteristics of nervios and ataques led to <strong>the</strong> misinterpretation of<br />

her perceptual distortions as psychotic symptoms, with consequences<br />

<strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> patient’s psychopharmacological treatment. Finally, <strong>the</strong> inpatient<br />

unit’s reliance on pharmacological ra<strong>the</strong>r than psycho<strong>the</strong>rapeutic<br />

interventions was not fully consonant with <strong>the</strong> patient’s treatment<br />

expectations.<br />

The lack of relevant <strong>cultural</strong> in<strong>for</strong>mation contrasts with <strong>the</strong> unit’s<br />

attention to more purely ethnic issues, such as <strong>the</strong> frequent use of<br />

Spanish interpreters to ensure <strong>the</strong> patient’s participation in <strong>the</strong><br />

milieu, and <strong>the</strong> focus on “ethnic matching” (45), achieved by assigning<br />

a Latino psychiatry resident to her care. The emphasis on ethnicity<br />

alone ra<strong>the</strong>r than culture is a problematic characteristic of contemporary<br />

US psychiatry that can lead, as in this case, to <strong>the</strong>rapeutic practices<br />

that only go partway toward eliciting <strong>the</strong> relevant points of difference<br />

in <strong>the</strong> patient’s presentation and treatment response (46). The use of<br />

Spanish, <strong>for</strong> example, is absolutely necessary <strong>for</strong> <strong>assessing</strong> a non-<br />

English speaking Latina such as this patient, but is not sufficient as<br />

a <strong>cultural</strong>ly valid intervention; <strong>for</strong> that, <strong>the</strong>rapeutic approaches based<br />

on <strong>cultural</strong> in<strong>for</strong>mation are also required. Ethnic matching does not<br />

guarantee access to this material, since persons from <strong>the</strong> same ethnic<br />

background can differ in terms of <strong>cultural</strong> experience and clinicians may

ROBERTO LEWIS-FERNÁNDEZ AND NAELYS DÍAZ 291<br />

be influenced less by <strong>the</strong>ir culture of origin than by <strong>the</strong>ir professional<br />

context.<br />

Referral to an outpatient clinic with an explicitly <strong>cultural</strong> focus resulted<br />

in a more comprehensive evaluation <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> patient, leading to a<br />

process of rediagnosis and to <strong>the</strong> implementation of psycho<strong>the</strong>rapeutic<br />

interventions more in accord with her expectations, with more successful<br />

clinical results.<br />

Overall Cultural Assessment<br />

The final section of <strong>the</strong> Cultural Formulation summarizes <strong>the</strong> in<strong>for</strong>mation<br />

in <strong>the</strong> previous sections, focusing on <strong>cultural</strong> material that contributes<br />

to diagnosis and treatment. The role that <strong>cultural</strong> features<br />

have played in determining overall illness outcome are particularly<br />

emphasized.<br />

In this case, <strong>the</strong> overall assessment would mention that <strong>the</strong> patient’s<br />

<strong>cultural</strong> identity is that of a rural Puerto Rican migrant with limited<br />

<strong>for</strong>mal education, who speaks Spanish exclusively and has only lived<br />

<strong>for</strong> limited periods in <strong>the</strong> US, resulting in minimal acculturation. Her<br />

psychopathology is expressed in <strong>the</strong> traditional Puerto Rican idioms of<br />

nervios and ataques de nervios. She attributed <strong>the</strong> origin of <strong>the</strong>se problems<br />

and her relapsing course to multiple past stressors and traumas,<br />

and especially to unresolved conflicts with her children resulting from<br />

her prolonged separation from <strong>the</strong>m during childhood. In fact, her clinical<br />

condition did not improve until <strong>the</strong>ir affective breach was addressed<br />

in family <strong>the</strong>rapy.<br />

The patient’s initial inpatient treatment proved ineffective partly<br />

because of <strong>the</strong> misattribution of a psychotic label to her perceptual<br />

distortions, which are normative idioms of distress <strong>for</strong> this <strong>cultural</strong><br />

group. Misdiagnosis exposed patient to <strong>the</strong> potentially toxic effects of<br />

antipsychotic medication and interfered with referral to family <strong>the</strong>rapy.<br />

In addition, lack of <strong>cultural</strong> in<strong>for</strong>mation also hindered <strong>the</strong> identification<br />

of patient’s underlying Axis II pathology and obscured <strong>the</strong><br />

relationship between her character disorder and her persistent Axis I<br />

symptoms, including her chronic suicidality and its exacerbations in<br />