Sharon-Weinberger-In.. - American Antigravity

Sharon-Weinberger-In.. - American Antigravity

Sharon-Weinberger-In.. - American Antigravity

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

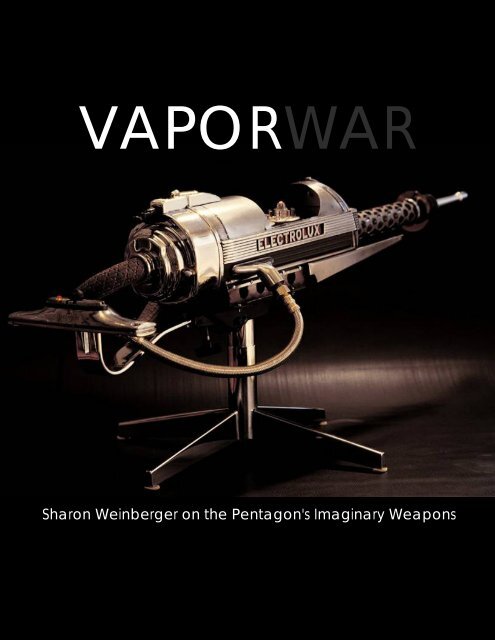

VAPORWAR<br />

<strong>Sharon</strong> <strong>Weinberger</strong> on the Pentagon's Imaginary Weapons<br />

Dream Come True: True <strong>Antigravity</strong> through the Veneficus<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Antigravity</strong>.Com Page 1 of 11

VAPORWAR<br />

<strong>Sharon</strong> <strong>Weinberger</strong> on the Pentagon's Imaginary Weapons<br />

By Tim Ventura and <strong>Sharon</strong> <strong>Weinberger</strong>, June 19th, 2006<br />

It's called a “hafnium bomb”, and it uses a new type of stimulated nuclear isomer technology so deadly<br />

that the Pentagon doesn't want you to even know that it exists -- and according to <strong>Sharon</strong> <strong>Weinberger</strong>,<br />

it doesn't. We join the intrepid editor of Aviation Week's Defense Technology <strong>In</strong>ternational as she takes<br />

us on a journey through the Pentagon's scientific underworld...<br />

AAG: Let's start out with a bit of background information: you're an experienced defenseindustry<br />

reporter and editor with lots of experience covering the latest trends in military<br />

technology. However, it appears that your new book, "Imaginary Weapons", goes in a radically<br />

new direction with a focus on overhyped vaporware defense technologies. I'm wondering if you<br />

could start us out with a bit about your personal background, and what really inspired you to<br />

begin writing this book?<br />

<strong>Weinberger</strong>: I have some background in<br />

national security studies, but I really stumbled into<br />

defense reporting when I moved to Washington<br />

after graduate school. I was looking, like all<br />

newcomers to DC, to find work that didn’t involve<br />

toting someone else’s briefcase. I eventually ended<br />

up working for a small Beltway company doing<br />

research and analysis for the Pentagon. I worked<br />

with some incredibly intelligent and thoughtful<br />

people, and went from there into defense<br />

journalism.<br />

One of the things I learned from that experience is<br />

that the defense industry is itself an “underworld”<br />

in many ways, and I try to give readers a feel for<br />

this is my book. I remember sitting in the office of<br />

the head of the defense company I was working<br />

at—the CEO started talking about the fallout<br />

shelter in his backyard, and lecturing me on how<br />

much dirt you need over your fallout shelter to<br />

protect against radiation, and what wind patterns<br />

mean for radioactive fallout. I suddenly realized<br />

how absolutely weird the conversation was, and yet<br />

not so weird for those in the defense industry. We<br />

were discussing fallout shelters the way other<br />

people discuss barbeques. When you reside in an<br />

“underworld,” it seems so normal, but if you step<br />

back and look at it as an outsider, then you’re<br />

struck by how perverse it all is.<br />

Imaginary Weapons: A journey through<br />

the Pentagon’s scientific underworld.<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Antigravity</strong>.Com Page 2 of 11

It’s not the vaporware per se that makes this an underworld, but the very odd culture of<br />

technology and national security. I don’t draw a line between the perverse and the normal<br />

cultures of defense technology—the two are intertwined because we are all so insulated from the<br />

outside world. I was inspired to try to describe this underworld—and my experience being in it—<br />

to others.<br />

AAG: My understanding is that while you examine several technologies in "Imaginary<br />

Weapons", the core story really involves something called hafnium-bomb, which you first heard<br />

about in a defense-briefing on Capitol Hill in 1998. Can you give us a bit of detail about the<br />

scope of technologies that you focus on in the book, and what it was about the hafnium bomb in<br />

particular that made it so central to this story?<br />

<strong>Weinberger</strong>: The book talks about some of<br />

the more controversial areas of science that have<br />

attracted military interest, including remote<br />

viewing (psychics), cold fusion and antimatter<br />

weapons. I do not list these areas with the idea of<br />

lumping them together as bad science, but rather,<br />

to point out how each of these subjects tends to<br />

attract support from the underworld.<br />

At one point, I considered writing this book as a<br />

collection of stories about the scientific<br />

underworld, but the feedback I got was: “You need<br />

a narrative to carry the reader long.” <strong>In</strong> that sense,<br />

the hafnium bomb is a trope for a larger story I was<br />

trying to tell about technology and national<br />

security.<br />

AAG: Speaking of the hafnium-bomb, I thought<br />

the idea sounded reasonable until I saw your<br />

website, which featured a "hafnium grenade"<br />

claimed to deliver a 2-kiloton yield. Now from a<br />

layman's perspective, my first thought is that a<br />

nuclear hand-grenade has some immediately<br />

obvious drawbacks to deployment, so how’d this<br />

one make it that far up the chain of command?<br />

Hafnium Grenade: A hand-grenade<br />

claiming to deliver a 2-kiloton nuclear blast?<br />

<strong>Weinberger</strong>: Lots of ideas sound reasonable until you look at the practical implications.<br />

To be fair, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), in its official briefings to<br />

Congress about hafnium, described the power of a 2,000 pound bomb in the package of a 50<br />

pound bomb. But even that is impractical, and, according to the experts, simply not feasible.<br />

AAG: Now to turn the question around a bit, I've heard rumors that Los Alamos has been<br />

playing with laser-triggered nuclear isomers for years: at least in the context of a quasi-stable<br />

fuel-pellet for use in nuclear space propulsion. Is it possible that this particular idea made it past<br />

the screeners because of simple name-recognition and maybe just a lack of close-scrutiny on the<br />

proposed implementation, or is the entire nuclear-isomer thing just a fish-story?<br />

<strong>Weinberger</strong>: Yes, Los Alamos has been a “hot bed” for nuclear isomer enthusiasts,<br />

although some of them may have retired by now. But it’s important to differentiate between<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Antigravity</strong>.Com Page 3 of 11

interest in nuclear isomers, and the specific 1998 results that sparked the debate over the<br />

“hafnium bomb.” What is primarily at issue in my book is an experiment conducted in 1998 that<br />

led a scientist in Texas to claim he had “triggered” the hafnium isomer (hafnium-178m2) using<br />

photons from a dental X-ray machine. Those results could not be reproduced by independent<br />

researchers, and the initial claims violated some laws of physics. However, this does not cover<br />

the entire range of isomer physics, just the specific idea of a nuclear hand grenade based on the<br />

hafnium isomer.<br />

AAG: <strong>In</strong> "The Social Life of <strong>In</strong>formation", Brown & Duguid made an excellent point that<br />

technology stories like the hafnium-bomb or even the Philadelphia Experiment are part of an<br />

oral-tradition that's an ingrained part of the engineering & defense culture. They believe that<br />

stories like this stick around because they contain inherent information value, but that like any<br />

metaphorical tale, the information is often seriously diluted & misinterpreted over time. Any<br />

thoughts on how this might affect these "cutting-edge" technologies as they filter up from the<br />

engineering to the administrative levels in industry & government?<br />

<strong>Weinberger</strong>: I love that idea, truly. Oral<br />

traditions are a wonderful thing, and you may well<br />

be right about how those work. <strong>In</strong> a sense, the<br />

isomer bomb has been one of those stories: every<br />

few years nuclear weapons scientists would say,<br />

“Hey, wouldn’t isomers make for a great bomb?”<br />

Then the scientists would discuss it, realize the<br />

limitations, and (usually) move on.<br />

But the hafnium bomb should not be equated with<br />

all isomer research. That would be unfortunate.<br />

The idea is not to discourage truly forward thinking<br />

ideas, but to ensure that the ideas we do fund are<br />

grounded in reality (and science). I do hope the<br />

hafnium bomb becomes a reminder of why you<br />

don’t want to go off the deep end.<br />

Carl Collins: The hafnium researcher in his<br />

laboratory at the University of Texas.<br />

AAG: I'd like to broaden our scope just a bit from the book itself to some examples<br />

throughout the defense-industry. First, I'd like to touch on what I call "me too" technologies,<br />

which I guess would include Darpa's massive push towards <strong>In</strong>formation Technology solutions<br />

for any and every problem they come up against. They invented the internet, and IT certainly<br />

offers flashy solutions, but do you think that they're over-investing in IT simply because it gets<br />

them publicity to push initiatives in this area?<br />

<strong>Weinberger</strong>: Every DARPA director wants a legacy. I’ve heard, very second-hand, that<br />

the current director wants it to be cognitive computing, and DARPA has put a lot of investment<br />

into that area. At the same time, the New York Times ran an article some time back on DARPA’s<br />

cutbacks on university funding for IT. I can’t say which areas are over or under-invested in---I<br />

simply haven’t looked at the budget in that sort of detail. Though I’m sometimes critical of<br />

DARPA, I think its portfolio is likely balanced to reflect the current exigencies of war, and that<br />

may be quite reasonable.<br />

AAG: Speaking of which, the mother of all over-hyped "me too" technologies these days is<br />

nanotechnology. I probably don't even need to list examples (MIT's nanotech armor), but I<br />

should point out that the fundamental basis for Drexlerian nanotechnology - the nanoassembler<br />

- is still decades away from being a reality. Is nanotech a defense-industry example<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Antigravity</strong>.Com Page 4 of 11

where they're pushing a dream towards reality, or is this a case where the people following this<br />

craze are driving everybody else over the edge of a cliff with unrealistic expectations?<br />

<strong>Weinberger</strong>: I want to be careful here, because again I haven’t examined the<br />

nanotechnology issue much, particularly as it pertains to defense. If I were to learn that it’s<br />

being overhyped in defense, that wouldn’t surprise me, because there’s a tendency to do that.<br />

Certainly defense companies still regard nanotech as very basic research---something to be left<br />

to the universities, and I don’t know how much<br />

Defense Department funding is going to<br />

nanotechnology at the moment.<br />

<strong>In</strong> a somewhat related area, I recently saw that<br />

some researchers in meta-materials (negative index<br />

of refraction) are touting the research as a possible<br />

application to stealth. Metamaterials started off a<br />

few years ago as a somewhat controversial area, but<br />

seem now to have moved solidly into advancing<br />

science with possible applications. But I can’t help<br />

but wonder if it seems to be a tad reaching (toward<br />

the arms of funding agencies) to claim applications<br />

in stealth. But, who knows?<br />

AAG: One area that I'd like to ask about is the<br />

difference between broad cross-organizational<br />

initiatives, such as the pressing need to eliminate<br />

IED's in Iraq, and the many "pet projects" that<br />

seem to fly under the radar. Can you comment at<br />

all on pet-projects in general, and whether they're<br />

more susceptible to going completely off-track into<br />

areas like the hafnium technology -- maybe as a<br />

result of insular development cultures or a lack of<br />

proper oversight?<br />

Defense Tech <strong>In</strong>ternational: Sept/Oct<br />

2005 issue, edited by <strong>Sharon</strong> <strong>Weinberger</strong>.<br />

<strong>Weinberger</strong>: I think the insular culture (or what I refer to as an underworld) can be a<br />

part of the problem with things going off track with some of the more wild ideas, but it’s not the<br />

only issue to consider. If you get a defense official who is dead set on an idea—to the exclusion of<br />

outside review, you can do some serious damage. I think that’s what happened with the hafnium<br />

bomb to a large degree. Is this a universal problem? I think the issue of “vested interests” of<br />

program officers in defense projects is a problem, but one that extends far beyond “fringe<br />

science” and into the mainstream defense establishment. There’s also a larger issue here: the<br />

general scientific decline that many are observing within our defense establishment.<br />

The IED issue is very different. There, we are trying to tap science and technology to find<br />

immediate solutions to a problem that may defy any technical panacea. It’s a tragedy—the most<br />

technologically advanced military in the world is being done incredible harm by the most<br />

rudimentary of weapons.<br />

AAG: Now organizationally, what role does the Bush (or any) administration play in these<br />

technologies - or are they below the level of the administration's awareness?<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Antigravity</strong>.Com Page 5 of 11

<strong>Weinberger</strong>: I think most of them are below the administration’s radar screen, and that<br />

perhaps is part of the problem. Top officials are focused on Iraq. So, it’s more a problem of<br />

neglect.<br />

AAG: What role does general fear, uncertainty, and doubt (FUD) about enemy capabilities<br />

play in pushing through otherwise untenable technologies? I mean, it seems like some of these<br />

initiatives are really sold on the idea that "somebody might beat us to it", which seems to play<br />

into a culture of generalized anxiety in the defense industry. Any thoughts on this?<br />

<strong>Weinberger</strong>: That’s a huge, huge driving<br />

factor in a lot of what the Pentagon does. Just<br />

about every defense technology official you’ll meet<br />

will say, “My job is to prevent technological<br />

surprise.” And then they’ll talk about Sputnik,<br />

Japanese torpedoes, Soviet subs, etc. All those<br />

things that “surprised us” in one way or another.<br />

But when you look at the things that surprised us,<br />

you have to think about why they surprised us. It<br />

wasn’t typically things that we thought violated the<br />

laws of physics, but rather technological advances<br />

that competitors had made and where our<br />

intelligence wasn’t very good. So, when we speak<br />

about the hafnium bomb and competitors, we have<br />

to ask: is this an intelligence problem or a physics<br />

problem?<br />

AAG: Speaking of FUD, I've heard rumblings<br />

about China being the next "Soviet Union", and I'm<br />

wondering if you have any thoughts on this aspect<br />

of military programs driving foreign policy? Could<br />

there be a "trickle-up" effect from the defenseindustry<br />

to the administration pushing this anxiety<br />

into the foreign policy area?<br />

DTI 2006: A focus on radar coverage in<br />

Jan/Feb 2006, a bimonthly AvWeek feature.<br />

<strong>Weinberger</strong>: Organizations operate like human beings—they want to grow, become<br />

richer, and live forever. The China threat might indeed be real, but certainly I see a tendency to<br />

hype their capabilities in specific areas as a convenient way to garner support for favored U.S.<br />

defense projects. But is the tail wagging the dog, as your question suggests? That I’m not so sure.<br />

Rather, I think those with interests in these technologies are simply happy to play upon an<br />

existing belief within the current administration.<br />

Just for the record, I think the notion of a “military-industry complex” is misunderstood. This<br />

idea presumes much more power than these industries have. The influence is less at the<br />

strategic level and more at what I call the tactical level (i.e. the revolving door of defense officials<br />

who move into private employment and vice versa).<br />

AAG: Do you think that our military intentionally inflates their claims about enemy<br />

capabilities to sustain their budgets? I think that the difference between the cold-war picture of<br />

the Soviet Union and the reality of their defense-capabilities was shocking to most people, and<br />

I'm wondering if this might have been intentional, or just a runaway side-effect of selfreinforcing<br />

perceptions about the unknown?<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Antigravity</strong>.Com Page 6 of 11

<strong>Weinberger</strong>: I’m not sure intentional is the right word. It’s very easy to make yourself<br />

believe in something you want to believe in. It’s certainly advantageous for some military<br />

officials to promote and hype particular foreign threats in the hopes of furthering their own pet<br />

projects. Yes, there were certainly some egregious examples of this during the Cold War, like the<br />

so-called missile gap, and the imaginary Soviet nuclear bomber. We must be vigilant and<br />

cautious of such claims.<br />

AAG: Now you've said that the hafnium-bomb wasn't supported by scientific evidence, and<br />

I'd like to use that to touch on the idea of subjectivism & politics in scientific review. <strong>In</strong> a<br />

political environment, when funding is at stake, how should the military involve scientific review<br />

for various ideas -- especially when the supposedly impartial scientific review panels seem to be<br />

so politically driven themselves?<br />

<strong>Weinberger</strong>: There is no perfect model, and peer review doesn’t work for everything.<br />

Jimmy Wales, the founder of Wikipedia, gave a really eloquent interview some time back<br />

describing how he first tried a model for Wikipedia<br />

using peer review by experts, and it failed dismally.<br />

Now look at the success of Wikipedia, with no<br />

experts and no peer review, but rather, a<br />

community of users who constantly improve upon<br />

the entries. I think it would be beautiful if somehow<br />

science evolved to this sort of “community of users”<br />

model, I just don’t know how it would be done.<br />

High-level physics is just not accessible to the<br />

masses (let alone the experimental equipment<br />

needed for, let’s say, high energy physics). [Just<br />

after writing this answer, I also note a New York<br />

Times article on how Wikipedia will start<br />

restricting edits of some entries—so that model<br />

isn’t perfect either.]<br />

Certainly the <strong>In</strong>ternet is helping us move to an<br />

open model for science in some areas, by allowing<br />

scientists in frontier (or “fringe”) science to publish<br />

on the web without the need for peer review. <strong>In</strong><br />

another arena, such as mass media, anyone now<br />

can create a blog, or a news site. The access to entry<br />

is low, and so it opens up the field. Some people in<br />

the media view this as a threat, but I think it’s just<br />

wonderful.<br />

Cutting Edge: DTI explores military robotics<br />

in its March/April 2006 special edition.<br />

Now, when it comes to funding of science, that’s another story. I just don’t know if there is a<br />

better model than peer review. It’s possible that peer review can promote group think, or that<br />

good ideas are quashed because they are competitive with those of the reviewers. There are<br />

elements of truth in these claims, I’m sure. But what’s the alternative?<br />

I think there could be a better model for government funding of truly far-reaching science. One<br />

method may be the old Advanced Energy Projects division of the Department of Energy. That<br />

office funded a lot of high-risk research using peer review at particular points to determine if a<br />

project could go forward, but it allowed some discretion by the director. That office is now gone,<br />

but I think reestablishing something along those lines makes a lot of sense, particularly with the<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Antigravity</strong>.Com Page 7 of 11

current concerns about energy. And, of course, wouldn’t we all love to have the old industrial<br />

labs, like GE? But that, I’m afraid, is a thing of the past.<br />

AAG: Another issue is the pervasive problem of "quick-fix" thinking: pushing marginally<br />

useful or generally inelegant solutions as short-term solutions that fail to address long-term<br />

problems? Maybe this comes out of corporate America's narrow-focus on quarterly-profits, but<br />

I'm wondering if the problem of fixing the symptoms rather than the cause isn't a real issue in<br />

terms of the defense industry as well?<br />

<strong>Weinberger</strong>: I don’t want to over-generalize, but I think we see this problem in how the<br />

Pentagon is addressing the threat of improvised explosive devices. Understandably, they want<br />

quick fixes, because it’s an immediate problem. But they also need to be funding basic science<br />

and technology in the hopes that we can come across breakthrough technologies that would help<br />

with this problem.<br />

AAG: Is there a point where our technological<br />

edge in a specific area becomes apparent enough<br />

that we should stop investing money in an already<br />

mature technology? For instance, if we can hit a<br />

thumbtack with a guided missile launched from an<br />

aircraft 5 miles away, is it worth spending millions<br />

a year to continue enhancing the technology?<br />

<strong>Weinberger</strong>: If money were free, I’d say,<br />

heck, let’s invest in all of it. Personally, I’d like to<br />

study why salt shakers can stand on their edge in a<br />

pile of salt—pondering this oddity has kept me<br />

awake through many a corporate dinner. Seriously,<br />

though, in a world of choices we must prioritize.<br />

However, in the case of maturing technology, I<br />

actually do believe in upgrades. After all, part of<br />

“technological surprise” can be when our<br />

competitors make advances in existing technology<br />

that we didn’t expect. So, it depends on the<br />

circumstance. I am more critical of the massive<br />

expenditures in something like, say, a new fighter<br />

aircraft, if we see that the superiority, relative to the<br />

financial costs, may not be warranted.<br />

DTI Goes To Sea: A focus on emerging<br />

naval stealth in the Nov/Dec 2005 issue.<br />

AAG: <strong>In</strong> a case like that, wouldn't it be better to push an initiative to reduce the cost of these<br />

mature technologies rather than enhance their effectiveness to the point of absurdity?<br />

<strong>Weinberger</strong>: I might actually disagree here slightly with this premise. Effectiveness is<br />

important---if you’re going to spend billions of dollars to deploy a missile defense system, then I<br />

would much rather that it is 95 percent effective than 75 percent effective. The question is<br />

whether we really need the capability in the first place, relative to the base investment. As I said<br />

in the question above, we need to be critical about the initial investments in expensive<br />

technology.<br />

AAG: Would vaporware weapons-projects have any tertiary value in terms of psychological<br />

warfare? Personally, I've always wondered if maybe some of the government non-answers about<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Antigravity</strong>.Com Page 8 of 11

UFO's might not be an intentional way of keeping the enemy guessing about exactly what kinds<br />

of uber-weapons we have hidden away in our arsenal.<br />

<strong>Weinberger</strong>: Never assume conspiracy when incompetence will suffice as an<br />

explanation. I think the government simply never figured out quite how to deal with all the UFO<br />

memos in its archives. Some people were worried about embarrassment, perhaps, and maybe<br />

some people were really worried about UFOs (possibly). People assume the government<br />

operates with one voice---it doesn’t. As for psychological warfare, I’m not sure government is<br />

that savvy.<br />

Let’s take another example. New Scientist recently reviewed my book, and although the review<br />

was really quite positive and thoughtful, the author ended by asserting that perhaps the hafnium<br />

bomb was an intentional effort to dupe our enemies into thinking we had a fantastic new<br />

weapon. Wow, what a marvelous thought. But I have to ask: On what does the reviewer base this<br />

assertion? As a journalist, I have looked at the documentation and evidence, and there is<br />

absolutely nothing that would lead me to support such a contention, so why should I write it? If<br />

indeed the purpose of investment in the hafnium bomb were to fool others into thinking we<br />

were on our way to a new fantastic arms race, then only Popular Mechanics and a handful of<br />

other publications were duped. The Russians, on the other hand, were making fun of the<br />

hafnium bomb almost from the start.<br />

Journalism, particularly as it pertains to national<br />

security, has a moral obligation to be responsible,<br />

and not to perpetuate fantasy, or a political agenda.<br />

I truly believe this.<br />

AAG: What happens to these programs after<br />

they disappear? Does the technology get<br />

reabsorbed into other projects, or do they literally<br />

crate up the research and stick in next to the Ark of<br />

the Covenant in that big warehouse at the end of<br />

<strong>In</strong>diana Jones?<br />

<strong>Weinberger</strong>: I like the Ark of the Covenant<br />

idea. I like to say that no bad idea ever dies at the<br />

Pentagon, it just ends up in another agency. These<br />

proposals lie dormant, and then are rediscovered<br />

and repackaged. I guess this is inevitable to some<br />

degree. I have no doubt that hafnium will rise like a<br />

phoenix from the ashes at some point—but when it<br />

does, I hope people say, “Remember the dental X-<br />

ray and the nuclear hand grenade?”<br />

Oil Crunch: DTI tackes military fuel supply<br />

logistics in it’s latest May/June 2006 issue.<br />

AAG: Do you think that the current SBIR<br />

process actually limits the development of new technologies? The reason I ask is that I've met<br />

many inventors with projects they'd love to get DoD financing for, but most of the time they end<br />

up getting pushed into trying to match their unique invention with an arcane list of "SBIR<br />

projects" (like stealth belt-buckles)?<br />

<strong>Weinberger</strong>: That’s funny—I love the idea of “stealth belt buckles.” You know, I think a<br />

study of the Small Business <strong>In</strong>novative Research (SBIR) process would be an excellent area for<br />

journalists to look into. Does it work? Could it work better? On one hand, you have an entire<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Antigravity</strong>.Com Page 9 of 11

usiness sector that wouldn’t exist were it not for the SBIR process. On the other hand, as you<br />

point out, you have the stealth belt buckle issue.<br />

But you have to understand why that exists. If you’re not solving a problem the military needs,<br />

what good are you doing, and who will buy your fabulous technology? On the other hand, I<br />

suppose if you want true innovation, you don’t want to overly limit proposals. Maybe the<br />

solution is to strike a balance between the two: practical problems and far-reaching ideas.<br />

AAG: What about over-engineering: the best example is NASA designing the space-pen with<br />

a pressure-loaded cartridge to write upside down without running dry, while the Russians<br />

effectively solved the same issue by issuing their cosmonauts pencils. Does the incentive to drive<br />

large, financially-profitable defense-contracts lead us towards these Rube Goldberg style<br />

approaches to solve everyday challenges, and has this been addressed at all in the defenseindustry?<br />

<strong>Weinberger</strong>: That’s a good question, but I would reply with, “it depends.” When you’re<br />

dealing with multibillion dollar weapon systems, you sometimes can’t afford for little things to<br />

go wrong. On the other hand, you don’t want to create a billion dollar solution to something a<br />

stick of gum can fix.<br />

“We should never dismiss any idea out of hand as being fringe...<br />

We should challenge orthodoxy and encourage free thinking.”<br />

AAG: I'd like to focus on aerospace for just a second, because I've talked to Nick Cook over at<br />

Janes a few times about industry trends, and he's very concerned that aerospace is going<br />

through a period of profound decline right now. For instance, the average age of most aerospace<br />

engineers is 55 years old, because the industry only produces refinements on mature<br />

technologies, which means that young innovators go for the high-paychecks & creative<br />

fulfillment of the IT industry rather than aerospace. Can you give us your thoughts on this<br />

industry, and whether it's really in decline or not?<br />

<strong>Weinberger</strong>: Cook is very correct. My brother for example, studied aerospace<br />

engineering at Stanford about 10 years ago, and like most of his colleagues, went into computer<br />

programming. That’s where the excitement was—aerospace wasn’t a fun or creative field to be<br />

in. There’s going to be a big crisis as the current generation of aerospace engineers retires; I<br />

don’t think anyone knows what to do about it. There needs to be a lot more funding for basic<br />

research and development—that will help attract younger workers. But I don’t know if that’s<br />

politically feasible right now. Where will the money come from?<br />

How to fix it? I’m just not sure. Maybe we need simply to accept that IT, and not aerospace, is<br />

the growth field. My guess is that for the aerospace industry to be reinvigorated, we’ll need the<br />

next breakthrough in propulsion—that technology that really will effectively get us to Mars and<br />

beyond. So, there needs to a big push into R&D, but I don’t see that money coming down the<br />

pike.<br />

AAG: Well as a professional who works across a variety of defense-related industries, which<br />

ones would you say are really on the upswing right now? Can you give us an idea of what the<br />

players & technologies are that are going to really be making an impact in 21st century defense?<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Antigravity</strong>.Com Page 10 of 11

<strong>Weinberger</strong>: I hate to make predictions; they are always wrong. I would say that<br />

directed energy is the “next big thing,” but then again, that’s been the next big thing for the past<br />

20 years. Who would have guessed that homemade bombs would be the big threat in the current<br />

war? Not me. I’m good with evidence, but bad with predictions. The future is unknown.<br />

AAG: Let's close on a personal note: can you tell us a bit about the projects that you're<br />

currently pursuing, and are you planning more books or perhaps public speaking engagements<br />

related to this one in the future?<br />

<strong>Weinberger</strong>: I’ll be doing a Q&A<br />

at Politics & Prose Bookstore on July 8,<br />

and another reading at the Strand in New<br />

York on July 10. Details of the events are<br />

available on the bookstores’ websites, and<br />

I welcome everyone to attend. Some of the<br />

subjects I deal with are controversial, and<br />

I know not everyone will agree with my<br />

views, so I invite debate.<br />

Right now, I’m in the middle of<br />

investigating another “fringe science” area<br />

the Pentagon has been involved in. I’d<br />

prefer not to discuss it too much right<br />

now, but it has important societal<br />

implications (particularly if it works).<br />

Pentagon City: What other breakthroughs can be<br />

found inside America’s most secure military facility?<br />

And that, by the way, is my final note: we should never, ever dismiss any idea out of hand as<br />

being fringe. Rather, we should investigate and study these ideas. We should challenge<br />

orthodoxy and encourage free thinking. But when all is said and done, we must make our<br />

judgments based on the evidence we have in hand, and we should expect the agencies<br />

responsible for national security to do the same. For me, that is the lesson of Iraq and WMD’s,<br />

as well as of the hafnium bomb…<br />

<strong>Sharon</strong> <strong>Weinberger</strong> is the editor-in-chief of Defense Technology <strong>In</strong>ternational, a bimonthly<br />

editorial supplement to Aviation Week & Space Technology. Her writing on science and<br />

technology has also appeared in Slate, and the Washington Post Magazine. For additional<br />

information on her latest projects, visit <strong>Sharon</strong>’s site online at Imaginary Weapons.com<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Antigravity</strong>.Com Page 11 of 11