The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

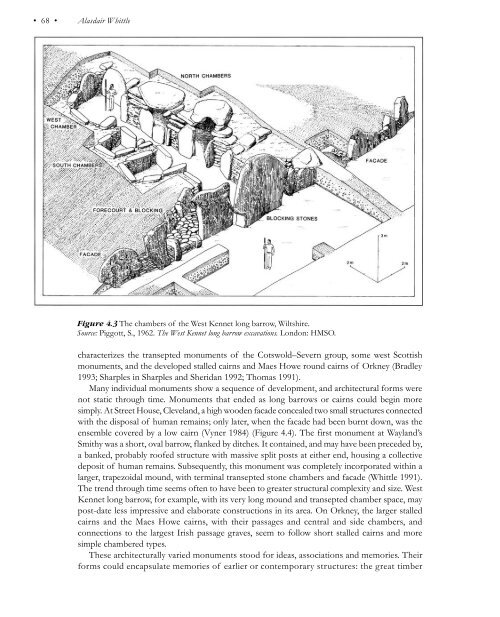

The Neolithic period • 67 • time. From the Middle Neolithic, more frequent single burials, under small mounds or in small enclosures, are encountered in certain regions. At Radley (Oxfordshire), a man and a woman were buried flexed in a pit within a ditched rectangle, which may have bounded a low barrow; they were accompanied by a shale or jet belt-slider and a partially polished flint knife respectively (Bradley 1992) (Figure 4.2). Other pre-Beaker Late Neolithic single burials include the successive inhumations within a deep grave pit, which was capped by a round barrow, at Duggleby Howe, Yorkshire (Kinnes 1979). Beaker funerary rites thus continued existing indigenous practice. Cremations are found throughout the Neolithic, from within the Etton causewayed enclosure to the first phase of Stonehenge. Human remains occur in other contexts, including the ditches and pits of causewayed enclosures, and later in henges. The excavated 20 per cent of the inner ditch of the Hambledon Hill causewayed enclosure, for example, revealed the remains of some 70 people. These were incomplete, including skulls lacking lower jaws and one truncated torso. The dead may have been exposed, or buried then excarnated, before being redeposited in significant places or circulated among the living, as tokens of indissoluble links with their ancestors. Something of this kind permeated the use of long barrows and chambered tombs. Rites were very varied, and funerals as such formed only part of them. In some, perhaps many, instances they certainly began with fleshed, recognizable individuals: witness the complete skeleton of an adult man inside the entrance of the north passage of Hazleton (Saville 1990). In others, corpses may, after initial treatments as discussed, only secondarily have been redeposited singly or together within the monuments (Whittle 1991). The end result was collective deposits of varying size, generally comprising the disarticulated and skeletally incomplete remains of a few or tens of people (and exceptionally more, as at Quanterness on Orkney). Monuments may not have been final resting places for all these remains. Some of the incompleteness (for example, too few skulls and longbones) may be accounted for by their successors’ circulation through and movements from such monuments (Thomas 1991). In some instances, the emphasis seems to have been on the accumulation, perhaps by successive rites and depositions, of an anonymous mass of intermingled white bone, representing the collectivity of the ancestors. In others, for example in transepted chambered tombs in the Cotswold-Severn area, as at West Kennet long barrow (Figure 4.3), or some of the Orcadian stalled cairns, including Midhowe, attention was certainly given to the placing of individual remains. At West Kennet, the basis of arrangement seems to have been gender and age: males in the end chamber; a predominance of adult males and females in the inner pair of opposed chambers; and principally the old and young in the outer pair (Thomas 1991). The structures in which these remains were temporarily or permanently stored may have stood for other ideas and associations than with the ancestral dead alone; some had only token human deposits or none at all (Bradley 1993). The terminology that has traditionally labelled them ‘tombs’ or ‘graves’ is unhelpful. All these monuments comprise a mound, cairn or platform, either housing or supporting roofed structures of wood or stone. The actual constructions from region to region and indeed within regions were very varied. Portal dolmens around the Irish Sea had large, stone, box-like chambers, some surrounded by low stone platforms. Court cairns in Ireland, and Clyde cairns in western Scotland, in essence elaborate this form, with larger cairns and divided chambers. Stone chambers set in the ends and sides of long barrows and long cairns occur in many areas, from southern England to the north of Scotland. Round cairns were a mainly northern form, with some in the west and some round barrows in Yorkshire. Many internal chambers or structures were single, and approached directly from outside the monument. In other instances, there was a connecting passage, with the chamber housed well within the mound. Internal spatial complexity

• 68 • Alasdair Whittle Figure 4.3 The chambers of the West Kennet long barrow, Wiltshire. Source: Piggott, S., 1962. The West Kennet long barrow excavations. London: HMSO. characterizes the transepted monuments of the Cotswold–Severn group, some west Scottish monuments, and the developed stalled cairns and Maes Howe round cairns of Orkney (Bradley 1993; Sharples in Sharples and Sheridan 1992; Thomas 1991). Many individual monuments show a sequence of development, and architectural forms were not static through time. Monuments that ended as long barrows or cairns could begin more simply. At Street House, Cleveland, a high wooden facade concealed two small structures connected with the disposal of human remains; only later, when the facade had been burnt down, was the ensemble covered by a low cairn (Vyner 1984) (Figure 4.4). The first monument at Wayland’s Smithy was a short, oval barrow, flanked by ditches. It contained, and may have been preceded by, a banked, probably roofed structure with massive split posts at either end, housing a collective deposit of human remains. Subsequently, this monument was completely incorporated within a larger, trapezoidal mound, with terminal transepted stone chambers and facade (Whittle 1991). The trend through time seems often to have been to greater structural complexity and size. West Kennet long barrow, for example, with its very long mound and transepted chamber space, may post-date less impressive and elaborate constructions in its area. On Orkney, the larger stalled cairns and the Maes Howe cairns, with their passages and central and side chambers, and connections to the largest Irish passage graves, seem to follow short stalled cairns and more simple chambered types. These architecturally varied monuments stood for ideas, associations and memories. Their forms could encapsulate memories of earlier or contemporary structures: the great timber

- Page 31 and 32: • 16 • Nicholas Barton —from

- Page 33 and 34: • 18 • Nicholas Barton Table 2.

- Page 35 and 36: • 20 • Nicholas Barton during t

- Page 37 and 38: • 22 • Nicholas Barton this per

- Page 39 and 40: • 24 • Nicholas Barton resemble

- Page 41 and 42: • 26 • Nicholas Barton Table 2.

- Page 43 and 44: • 28 • Nicholas Barton that it

- Page 45 and 46: • 30 • Nicholas Barton Figure 2

- Page 47 and 48: • 32 • Nicholas Barton Figure 2

- Page 49 and 50: • 34 • Nicholas Barton Walker,

- Page 51 and 52: • 36 • Steven Mithen substantia

- Page 53 and 54: • 38 • Steven Mithen locations.

- Page 55 and 56: • 40 • Steven Mithen Figure 3.4

- Page 57 and 58: • 42 • Steven Mithen Figure 3.6

- Page 59 and 60: • 44 • Steven Mithen from work

- Page 61 and 62: • 46 • Steven Mithen use of obs

- Page 63 and 64: • 48 • Steven Mithen provided e

- Page 65 and 66: • 50 • Steven Mithen Attempts h

- Page 67 and 68: • 52 • Steven Mithen may reflec

- Page 69 and 70: • 54 • Steven Mithen seeds from

- Page 71 and 72: • 56 • Steven Mithen Pollard, T

- Page 73 and 74: Chapter Four The Neolithic period,

- Page 75 and 76: • 60 • Alasdair Whittle graves

- Page 77 and 78: • 62 • Alasdair Whittle resourc

- Page 79 and 80: • 64 • Alasdair Whittle Figure

- Page 81: • 66 • Alasdair Whittle other s

- Page 85 and 86: • 70 • Alasdair Whittle inter-

- Page 87 and 88: • 72 • Alasdair Whittle hundred

- Page 89 and 90: • 74 • Alasdair Whittle and els

- Page 91 and 92: • 76 • Alasdair Whittle Moffett

- Page 93 and 94: • 78 • Mike Parker Pearson diff

- Page 95 and 96: • 80 • Mike Parker Pearson Figu

- Page 97 and 98: • 82 • Mike Parker Pearson argu

- Page 99 and 100: • 84 • Mike Parker Pearson Late

- Page 101 and 102: • 86 • Mike Parker Pearson been

- Page 103 and 104: • 88 • Mike Parker Pearson Figu

- Page 105 and 106: • 90 • Mike Parker Pearson are

- Page 107 and 108: • 92 • Mike Parker Pearson Bron

- Page 109 and 110: • 94 • Mike Parker Pearson Elli

- Page 111 and 112: • 96 • Timothy Champion For the

- Page 113 and 114: • 98 • Timothy Champion Perhaps

- Page 115 and 116: • 100 • Timothy Champion Figure

- Page 117 and 118: • 102 • Timothy Champion Little

- Page 119 and 120: • 104 • Timothy Champion CRAFT,

- Page 121 and 122: • 106 • Timothy Champion solely

- Page 123 and 124: • 108 • Timothy Champion and re

- Page 125 and 126: • 110 • Timothy Champion range

- Page 127 and 128: • 112 • Timothy Champion Coles,

- Page 129 and 130: • 114 • Colin Haselgrove votive

- Page 131 and 132: • 116 • Colin Haselgrove Figure

• 68 • Alasdair Whittle<br />

Figure 4.3 <strong>The</strong> chambers <strong>of</strong> the West Kennet long barrow, Wiltshire.<br />

Source: Piggott, S., 1962. <strong>The</strong> West Kennet long barrow ex<strong>ca</strong>vations. London: HMSO.<br />

characterizes the transepted monuments <strong>of</strong> the Cotswold–Severn group, some west Scottish<br />

monuments, and the developed stalled <strong>ca</strong>irns and Maes Howe round <strong>ca</strong>irns <strong>of</strong> Orkney (Bradley<br />

1993; Sharples in Sharples and Sheridan 1992; Thomas 1991).<br />

Many individual monuments show a sequence <strong>of</strong> development, and architectural forms were<br />

not static through time. Monuments that ended as long barrows or <strong>ca</strong>irns could begin more<br />

simply. At Street House, Cleveland, a high wooden fa<strong>ca</strong>de concealed two small structures connected<br />

with the disposal <strong>of</strong> human remains; only later, when the fa<strong>ca</strong>de had been burnt down, was the<br />

ensemble covered by a low <strong>ca</strong>irn (Vyner 1984) (Figure 4.4). <strong>The</strong> first monument at Wayland’s<br />

Smithy was a short, oval barrow, flanked by ditches. It contained, and may have been preceded by,<br />

a banked, probably ro<strong>of</strong>ed structure with massive split posts at either end, housing a collective<br />

deposit <strong>of</strong> human remains. Subsequently, this monument was completely incorporated within a<br />

larger, trapezoidal mound, with terminal transepted stone chambers and fa<strong>ca</strong>de (Whittle 1991).<br />

<strong>The</strong> trend through time seems <strong>of</strong>ten to have been to greater structural complexity and size. West<br />

Kennet long barrow, for example, with its very long mound and transepted chamber space, may<br />

post-date less impressive and elaborate constructions in its area. On Orkney, the larger stalled<br />

<strong>ca</strong>irns and the Maes Howe <strong>ca</strong>irns, with their passages and central and side chambers, and<br />

connections to the largest Irish passage graves, seem to follow short stalled <strong>ca</strong>irns and more<br />

simple chambered types.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se architecturally varied monuments stood for ideas, associations and memories. <strong>The</strong>ir<br />

forms could en<strong>ca</strong>psulate memories <strong>of</strong> earlier or contemporary structures: the great timber