The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

The Lateglacial colonization of Britain • 31 • Farm (Oxfordshire), they usually contain a high proportion of blade waste to retouched tools, the latter making up less than 2 per cent of the assemblage. The absence of hearth structures and burnt flints from all these sites implies that they were occupied for short durations, perhaps mainly relating to knapping and blade manufacture. Parallels for these British ‘long blade’ sites can be found in the Ahrensburgian of northern Germany, particularly in assemblages of the Eggstedt-Stellmoor group, characterized by ‘large’ and ‘giant’ blades (Gross- and Riesenklingen as defined in Taute 1968). The best known site is Stellmoor, where the ages of nine individually dated reindeer bones and antlers from the Ahrensburgian layer give a pooled age of 9,995 ±34 BP (Cook and Jacobi 1994). However, Ahrensburgian sites tend to include small tanged points (Stielspitzen) and, with the exception of Avington VI, this component is so far missing in British ‘long blade’ assemblages. In northern France, similar ‘long blade’ material has been described from the Figure 2.10 Distribution of Final Upper Palaeolithic ‘long blade’ findspots with bruised blades (lames mâchurées): 1. Avington VI; 2. Gatehampton Farm; 3. Three Ways Wharf; 4. Springhead; 5. Riverdale; 6. Sproughton; 7. Swaffham Prior. Somme Valley and the Paris Basin, where it is attributed to the so-called industries à pieces mâchurées. These assemblages also display a notable absence of small tanged points. Where bone is preserved in the French sites, it is derived from either wild horse or bovids, rather than reindeer. Four AMS dates on horse teeth from the site at Belloy-sur-Somme in Picardy range from 10,260±160 BP to 9,720±130 BP, and overlap in age with the Three Ways Wharf site. Other findspots in Britain of potentially comparable age include Risby Warren (Humberside), where small Ahrensburgian points were recorded in an assemblage from above the equivalent of a Younger Dryas Coversand deposit, and Tayfen Road, Bury St Edmunds (Suffolk) and Doniford Cliff (Somerset), where single specimens of Ahrensburgian points are known. At none of these locations, however, were any long blades recovered. Thus it remains to be determined whether the tanged point sites are chronologically equivalent to those of ‘long blade’ type. The proximity of Risby Warren to the Younger Dryas North Sea shoreline and the similar coastal position of Ahrensburgian sites in southern Scandinavia and northern Germany may point to the seasonal exploitation of various marine food sources in addition to reindeer. Remains of seals, whales and fish have been recorded in some of the Scandinavian sites (Eriksen in Larsson 1996). A date of 9940±100 BP on domesticated dog from Seamer Carr (North Yorkshire), not far from Risby,

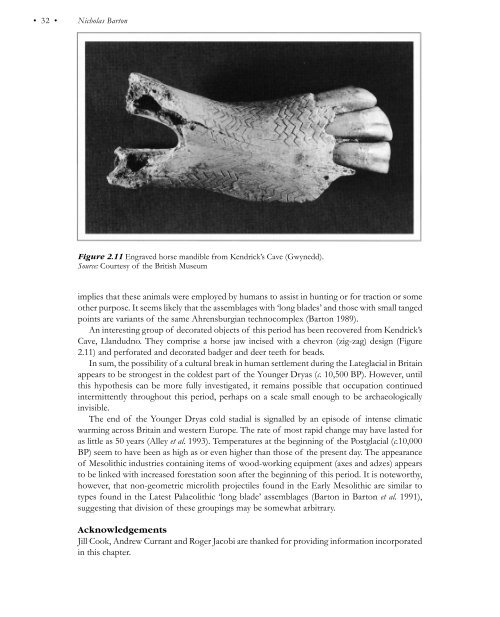

• 32 • Nicholas Barton Figure 2.11 Engraved horse mandible from Kendrick’s Cave (Gwynedd). Source: Courtesy of the British Museum implies that these animals were employed by humans to assist in hunting or for traction or some other purpose. It seems likely that the assemblages with ‘long blades’ and those with small tanged points are variants of the same Ahrensburgian technocomplex (Barton 1989). An interesting group of decorated objects of this period has been recovered from Kendrick’s Cave, Llandudno. They comprise a horse jaw incised with a chevron (zig-zag) design (Figure 2.11) and perforated and decorated badger and deer teeth for beads. In sum, the possibility of a cultural break in human settlement during the Lateglacial in Britain appears to be strongest in the coldest part of the Younger Dryas (c. 10,500 BP). However, until this hypothesis can be more fully investigated, it remains possible that occupation continued intermittently throughout this period, perhaps on a scale small enough to be archaeologically invisible. The end of the Younger Dryas cold stadial is signalled by an episode of intense climatic warming across Britain and western Europe. The rate of most rapid change may have lasted for as little as 50 years (Alley et al. 1993). Temperatures at the beginning of the Postglacial (c.10,000 BP) seem to have been as high as or even higher than those of the present day. The appearance of Mesolithic industries containing items of wood-working equipment (axes and adzes) appears to be linked with increased forestation soon after the beginning of this period. It is noteworthy, however, that non-geometric microlith projectiles found in the Early Mesolithic are similar to types found in the Latest Palaeolithic ‘long blade’ assemblages (Barton in Barton et al. 1991), suggesting that division of these groupings may be somewhat arbitrary. Acknowledgements Jill Cook, Andrew Currant and Roger Jacobi are thanked for providing information incorporated in this chapter.

- Page 2: The Archaeology of Britain The Arch

- Page 5 and 6: First published 1999 by Routledge 1

- Page 7 and 8: • vi • Contents Chapter Eight R

- Page 9 and 10: • viii • Figures 5.3 Ceramic ch

- Page 11 and 12: • x • Figures 15.5 Garden and l

- Page 13 and 14: • xii • Contributors Landscape

- Page 15 and 16: Preface The idea for the approach t

- Page 17 and 18: • 2 • Ian Ralston and John Hunt

- Page 19 and 20: • 4 • Ian Ralston and John Hunt

- Page 21 and 22: • 6 • Ian Ralston and John Hunt

- Page 23 and 24: • 8 • Ian Ralston and John Hunt

- Page 25 and 26: • 10 • Ian Ralston and John Hun

- Page 27 and 28: • 12 • Ian Ralston and John Hun

- Page 29 and 30: • 14 • Nicholas Barton Table 2.

- Page 31 and 32: • 16 • Nicholas Barton —from

- Page 33 and 34: • 18 • Nicholas Barton Table 2.

- Page 35 and 36: • 20 • Nicholas Barton during t

- Page 37 and 38: • 22 • Nicholas Barton this per

- Page 39 and 40: • 24 • Nicholas Barton resemble

- Page 41 and 42: • 26 • Nicholas Barton Table 2.

- Page 43 and 44: • 28 • Nicholas Barton that it

- Page 45: • 30 • Nicholas Barton Figure 2

- Page 49 and 50: • 34 • Nicholas Barton Walker,

- Page 51 and 52: • 36 • Steven Mithen substantia

- Page 53 and 54: • 38 • Steven Mithen locations.

- Page 55 and 56: • 40 • Steven Mithen Figure 3.4

- Page 57 and 58: • 42 • Steven Mithen Figure 3.6

- Page 59 and 60: • 44 • Steven Mithen from work

- Page 61 and 62: • 46 • Steven Mithen use of obs

- Page 63 and 64: • 48 • Steven Mithen provided e

- Page 65 and 66: • 50 • Steven Mithen Attempts h

- Page 67 and 68: • 52 • Steven Mithen may reflec

- Page 69 and 70: • 54 • Steven Mithen seeds from

- Page 71 and 72: • 56 • Steven Mithen Pollard, T

- Page 73 and 74: Chapter Four The Neolithic period,

- Page 75 and 76: • 60 • Alasdair Whittle graves

- Page 77 and 78: • 62 • Alasdair Whittle resourc

- Page 79 and 80: • 64 • Alasdair Whittle Figure

- Page 81 and 82: • 66 • Alasdair Whittle other s

- Page 83 and 84: • 68 • Alasdair Whittle Figure

- Page 85 and 86: • 70 • Alasdair Whittle inter-

- Page 87 and 88: • 72 • Alasdair Whittle hundred

- Page 89 and 90: • 74 • Alasdair Whittle and els

- Page 91 and 92: • 76 • Alasdair Whittle Moffett

- Page 93 and 94: • 78 • Mike Parker Pearson diff

- Page 95 and 96: • 80 • Mike Parker Pearson Figu

• 32 • Nicholas Barton<br />

Figure 2.11 Engraved horse mandible <strong>from</strong> Kendrick’s Cave (Gwynedd).<br />

Source: Courtesy <strong>of</strong> the British Museum<br />

implies that these animals were employed by humans to assist in hunting or for traction or some<br />

other purpose. It seems likely that the assemblages with ‘long blades’ and those with small tanged<br />

points are variants <strong>of</strong> the same Ahrensburgian technocomplex (Barton 1989).<br />

<strong>An</strong> interesting group <strong>of</strong> decorated objects <strong>of</strong> this period has been recovered <strong>from</strong> Kendrick’s<br />

Cave, Llandudno. <strong>The</strong>y comprise a horse jaw incised with a chevron (zig-zag) design (Figure<br />

2.11) and perforated and decorated badger and deer teeth for beads.<br />

In sum, the possibility <strong>of</strong> a cultural break in human settlement during the Lateglacial in <strong>Britain</strong><br />

appears to be strongest in the coldest part <strong>of</strong> the Younger Dryas (c. 10,500 BP). However, until<br />

this hypothesis <strong>ca</strong>n be more fully investigated, it remains possible that occupation continued<br />

intermittently throughout this period, perhaps on a s<strong>ca</strong>le small enough to be archaeologi<strong>ca</strong>lly<br />

invisible.<br />

<strong>The</strong> end <strong>of</strong> the Younger Dryas cold stadial is signalled by an episode <strong>of</strong> intense climatic<br />

warming across <strong>Britain</strong> and western Europe. <strong>The</strong> rate <strong>of</strong> most rapid change may have lasted for<br />

as little as 50 years (Alley et al. 1993). Temperatures at the beginning <strong>of</strong> the Postglacial (c.10,000<br />

BP) seem to have been as high as or even higher than those <strong>of</strong> the present day. <strong>The</strong> appearance<br />

<strong>of</strong> Mesolithic industries containing items <strong>of</strong> wood-working equipment (axes and adzes) appears<br />

to be linked with increased forestation soon after the beginning <strong>of</strong> this period. It is noteworthy,<br />

however, that non-geometric microlith projectiles found in the Early Mesolithic are similar to<br />

types found in the Latest Palaeolithic ‘long blade’ assemblages (Barton in Barton et al. 1991),<br />

suggesting that division <strong>of</strong> these groupings may be somewhat arbitrary.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Jill Cook, <strong>An</strong>drew Currant and Roger Jacobi are thanked for providing information incorporated<br />

in this chapter.