The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

The Lateglacial colonization of Britain • 21 • controlling rope movement (e.g. in climbing or for lassooing animals). Such items could have been stored or made on naturally shed antler and need not imply local hunting. Similarly, finds of mammoth ivory baguettes at Gough’s Cave and Kent’s Cavern, and reindeer antler sagaies at Church Hole and Fox Hole (Derbyshire), prove only that these materials were brought in by humans and possibly left for some future purpose. Apart from these rare objects, there is in fact very little convincing evidence for caching or storage associated with Creswellian sites. However, if dried meat and fat had been stored, this would doubtless have been in an archaeologically invisible form. The absence of cut-marked reindeer bone (as opposed to artefacts) from sites dating to the first phase of the Interstadial is an interesting phenomenon. According to Bratlund (in Larsson 1996), contemporary Upper Palaeolithic sites in north-west Europe (Hamburgian, Later Magdalenian) invariably contain evidence of either horse or reindeer, but rarely both. When horse dominates the fauna, the seasonal evidence tends to favour summer and winter hunting, whilst reindeer seems to have been trapped predominantly in the autumn and spring. Accordingly, it is theoretically possible that Creswellian sites represent summer and/or winter hunting locations, rather than those used during the intervening seasons. Alternatively, a climatic explanation might be sought for the absence of reindeer in Britain during the warmest part of the Interstadial (Jacobi in Fagnart and Thevenin 1997). Some additional information on seasonality is forthcoming from Whooper swan (Cygnus cygnus) remains recovered at Gough’s Cave. One end of a humerus and part of an ulna display grooves and cut-marks connected with the removal of needle blanks. Since this large migratory bird is normally a winter visitor to Britain, its presence at the cave may be taken as plausible evidence for human activity in this season. Whether the British Creswellian cave sites like Gough’s Cave or Kent’s Cavern served as ‘task locations’ or longer term residential sites is difficult to determine on present evidence. Certainly, more than just ephemeral activities seem to be indicated by the range of equipment recorded at both sites. Collectively, they imply sewing and needle making, as well as hide working and the processing of animal carcasses. At the same time, it may be significant that tools like micropiercers (microperçoirs), delicate enough for making small incisions in bone and antler, are found at Gough’s Cave, one of the few sites where there is direct evidence for engraved items in these materials (see below). One component, still largely missing from the record, are the Creswellian open-air equivalents of cave sites, which might be predicted to occur in the non-limestone areas in the east of the country. So far, relatively few such findspots are known, but they are likely to include flintwork from Newark (Nottinghamshire), Edlington Wood (Yorkshire), Froggatt (Derbyshire), Lakenheath Warren (Suffolk) and Walton-on-the-Naze (Essex), owing to the presence of blades with typical en éperon butts at each of these localities (Jacobi in Fagnart and Thevenin 1997). If these were winter occupation sites, they might be expected to contain evidence of substantial dwelling structures with post-settings, boiling pits and internal fireplaces. Such structures have been found in the German Rhineland at Gönnersdorf, where there is also evidence of winter occupation. On the other hand, if sites were occupied in the autumn and spring, they might be expected to resemble more closely open-air locations in the Paris Basin (e.g. Pincevent; Verberie), where tent-like arrangements have been found alongside outdoor hearths with flat stone cooking slabs. Burials Although human remains have been recorded at a number of Creswellian sites, very few can be proven by AMS dating to be of Lateglacial age. Amongst the examples definitely attributable to

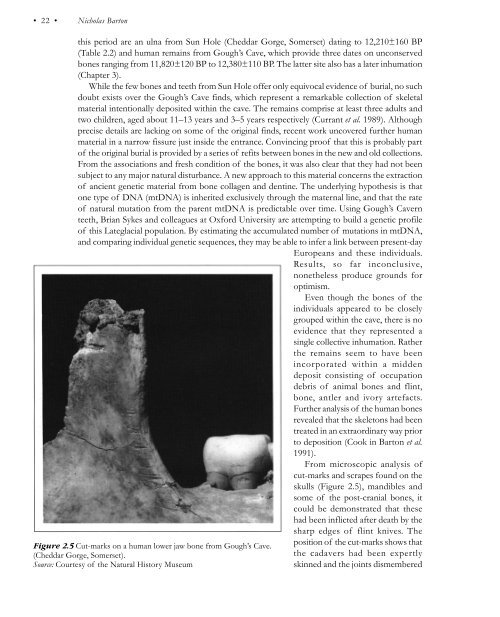

• 22 • Nicholas Barton this period are an ulna from Sun Hole (Cheddar Gorge, Somerset) dating to 12,210±160 BP (Table 2.2) and human remains from Gough’s Cave, which provide three dates on unconserved bones ranging from 11,820±120 BP to 12,380±110 BP. The latter site also has a later inhumation (Chapter 3). While the few bones and teeth from Sun Hole offer only equivocal evidence of burial, no such doubt exists over the Gough’s Cave finds, which represent a remarkable collection of skeletal material intentionally deposited within the cave. The remains comprise at least three adults and two children, aged about 11–13 years and 3–5 years respectively (Currant et al. 1989). Although precise details are lacking on some of the original finds, recent work uncovered further human material in a narrow fissure just inside the entrance. Convincing proof that this is probably part of the original burial is provided by a series of refits between bones in the new and old collections. From the associations and fresh condition of the bones, it was also clear that they had not been subject to any major natural disturbance. A new approach to this material concerns the extraction of ancient genetic material from bone collagen and dentine. The underlying hypothesis is that one type of DNA (mtDNA) is inherited exclusively through the maternal line, and that the rate of natural mutation from the parent mtDNA is predictable over time. Using Gough’s Cavern teeth, Brian Sykes and colleagues at Oxford University are attempting to build a genetic profile of this Lateglacial population. By estimating the accumulated number of mutations in mtDNA, and comparing individual genetic sequences, they may be able to infer a link between present-day Europeans and these individuals. Results, so far inconclusive, nonetheless produce grounds for optimism. Even though the bones of the individuals appeared to be closely grouped within the cave, there is no evidence that they represented a single collective inhumation. Rather the remains seem to have been incorporated within a midden deposit consisting of occupation debris of animal bones and flint, bone, antler and ivory artefacts. Further analysis of the human bones revealed that the skeletons had been treated in an extraordinary way prior to deposition (Cook in Barton et al. 1991). From microscopic analysis of cut-marks and scrapes found on the skulls (Figure 2.5), mandibles and some of the post-cranial bones, it could be demonstrated that these had been inflicted after death by the sharp edges of flint knives. The Figure 2.5 Cut-marks on a human lower jaw bone from Gough’s Cave. (Cheddar Gorge, Somerset). Source: Courtesy of the Natural History Museum position of the cut-marks shows that the cadavers had been expertly skinned and the joints dismembered

- Page 2: The Archaeology of Britain The Arch

- Page 5 and 6: First published 1999 by Routledge 1

- Page 7 and 8: • vi • Contents Chapter Eight R

- Page 9 and 10: • viii • Figures 5.3 Ceramic ch

- Page 11 and 12: • x • Figures 15.5 Garden and l

- Page 13 and 14: • xii • Contributors Landscape

- Page 15 and 16: Preface The idea for the approach t

- Page 17 and 18: • 2 • Ian Ralston and John Hunt

- Page 19 and 20: • 4 • Ian Ralston and John Hunt

- Page 21 and 22: • 6 • Ian Ralston and John Hunt

- Page 23 and 24: • 8 • Ian Ralston and John Hunt

- Page 25 and 26: • 10 • Ian Ralston and John Hun

- Page 27 and 28: • 12 • Ian Ralston and John Hun

- Page 29 and 30: • 14 • Nicholas Barton Table 2.

- Page 31 and 32: • 16 • Nicholas Barton —from

- Page 33 and 34: • 18 • Nicholas Barton Table 2.

- Page 35: • 20 • Nicholas Barton during t

- Page 39 and 40: • 24 • Nicholas Barton resemble

- Page 41 and 42: • 26 • Nicholas Barton Table 2.

- Page 43 and 44: • 28 • Nicholas Barton that it

- Page 45 and 46: • 30 • Nicholas Barton Figure 2

- Page 47 and 48: • 32 • Nicholas Barton Figure 2

- Page 49 and 50: • 34 • Nicholas Barton Walker,

- Page 51 and 52: • 36 • Steven Mithen substantia

- Page 53 and 54: • 38 • Steven Mithen locations.

- Page 55 and 56: • 40 • Steven Mithen Figure 3.4

- Page 57 and 58: • 42 • Steven Mithen Figure 3.6

- Page 59 and 60: • 44 • Steven Mithen from work

- Page 61 and 62: • 46 • Steven Mithen use of obs

- Page 63 and 64: • 48 • Steven Mithen provided e

- Page 65 and 66: • 50 • Steven Mithen Attempts h

- Page 67 and 68: • 52 • Steven Mithen may reflec

- Page 69 and 70: • 54 • Steven Mithen seeds from

- Page 71 and 72: • 56 • Steven Mithen Pollard, T

- Page 73 and 74: Chapter Four The Neolithic period,

- Page 75 and 76: • 60 • Alasdair Whittle graves

- Page 77 and 78: • 62 • Alasdair Whittle resourc

- Page 79 and 80: • 64 • Alasdair Whittle Figure

- Page 81 and 82: • 66 • Alasdair Whittle other s

- Page 83 and 84: • 68 • Alasdair Whittle Figure

- Page 85 and 86: • 70 • Alasdair Whittle inter-

• 22 • Nicholas Barton<br />

this period are an ulna <strong>from</strong> Sun Hole (Cheddar Gorge, Somerset) dating to 12,210±160 BP<br />

(Table 2.2) and human remains <strong>from</strong> Gough’s Cave, which provide three dates on unconserved<br />

bones ranging <strong>from</strong> 11,820±120 BP to 12,380±110 BP. <strong>The</strong> latter site also has a later inhumation<br />

(Chapter 3).<br />

While the few bones and teeth <strong>from</strong> Sun Hole <strong>of</strong>fer only equivo<strong>ca</strong>l evidence <strong>of</strong> burial, no such<br />

doubt exists over the Gough’s Cave finds, which represent a remarkable collection <strong>of</strong> skeletal<br />

material intentionally deposited within the <strong>ca</strong>ve. <strong>The</strong> remains comprise at least three adults and<br />

two children, aged about 11–13 years and 3–5 years respectively (Currant et al. 1989). Although<br />

precise details are lacking on some <strong>of</strong> the original finds, recent work uncovered further human<br />

material in a narrow fissure just inside the entrance. Convincing pro<strong>of</strong> that this is probably part<br />

<strong>of</strong> the original burial is provided by a series <strong>of</strong> refits between bones in the new and old collections.<br />

From the associations and fresh condition <strong>of</strong> the bones, it was also clear that they had not been<br />

subject to any major natural disturbance. A new approach to this material concerns the extraction<br />

<strong>of</strong> ancient genetic material <strong>from</strong> bone collagen and dentine. <strong>The</strong> underlying hypothesis is that<br />

one type <strong>of</strong> DNA (mtDNA) is inherited exclusively through the maternal line, and that the rate<br />

<strong>of</strong> natural mutation <strong>from</strong> the parent mtDNA is predictable over time. Using Gough’s Cavern<br />

teeth, Brian Sykes and colleagues at Oxford University are attempting to build a genetic pr<strong>of</strong>ile<br />

<strong>of</strong> this Lateglacial population. By estimating the accumulated number <strong>of</strong> mutations in mtDNA,<br />

and comparing individual genetic sequences, they may be able to infer a link between present-day<br />

Europeans and these individuals.<br />

Results, so far inconclusive,<br />

nonetheless produce grounds for<br />

optimism.<br />

Even though the bones <strong>of</strong> the<br />

individuals appeared to be closely<br />

grouped within the <strong>ca</strong>ve, there is no<br />

evidence that they represented a<br />

single collective inhumation. Rather<br />

the remains seem to have been<br />

incorporated within a midden<br />

deposit consisting <strong>of</strong> occupation<br />

debris <strong>of</strong> animal bones and flint,<br />

bone, antler and ivory artefacts.<br />

Further analysis <strong>of</strong> the human bones<br />

revealed that the skeletons had been<br />

treated in an extraordinary way prior<br />

to deposition (Cook in Barton et al.<br />

1991).<br />

From microscopic analysis <strong>of</strong><br />

cut-marks and scrapes found on the<br />

skulls (Figure 2.5), mandibles and<br />

some <strong>of</strong> the post-cranial bones, it<br />

could be demonstrated that these<br />

had been inflicted after death by the<br />

sharp edges <strong>of</strong> flint knives. <strong>The</strong><br />

Figure 2.5 Cut-marks on a human lower jaw bone <strong>from</strong> Gough’s Cave.<br />

(Cheddar Gorge, Somerset).<br />

Source: Courtesy <strong>of</strong> the Natural History Museum<br />

position <strong>of</strong> the cut-marks shows that<br />

the <strong>ca</strong>davers had been expertly<br />

skinned and the joints dismembered