The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

Landscape and townscape from AD 1500 • 267 • cruck frames still in place. Houses of this type may have required more regular maintenance than their successors with mortared stone walls and slate roofs but were not necessarily less durable. They were demolished in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries not because they were no longer usable but because they could not be readily converted to accommodate current fashions in housing and rises in living standards. Post medieval housing styles first appear in southern England before 1500, generated by profits from production for the London market and rents that lagged behind rising prices. Medieval halls were floored over and chimneys and staircases installed to provide greater privacy, comfort and warmth. Brick began to replace wattle and daub with timber framing, while glass was used more extensively. Figure 15.1 Shieling huts, Lewis, Scotland, probably dating from the late nineteenth or early twentieth centuries. Source: I. Whyte Even within southern England there was a mosaic of rural economies, some of them less well integrated into the market than others, so that there can be distinct local variations in the timing of housing improvements. Regional variations in the evolution of peasant houses from medieval times onwards are still far from clear. In the North York Moors, for example, a sizeable group of modified longhouses survives, but in the Yorkshire Pennines, if such houses were common in medieval times, few now exist. Longhouse layouts continued, with upgraded standards of comfort in parts of England, such as Devon, into the eighteenth century, while laithe houses, with farmhouse and outbuildings constructed as a continuous range but without a common entrance, continued to be built in the Yorkshire Pennines and the Lancashire lowlands well into the nineteenth century. The ‘Great Rebuilding’ of rural England, first identified by Hoskins, took a century or more to penetrate to many parts of northern England. In less prosperous areas, like Wales and especially Scotland, traditional housing styles and construction techniques remained in use through the eighteenth century and later. Many people continued to live with their animals in longhouses. Only gradually were such dwellings upgraded, with the byre being turned into storage accommodation. Upland Wales preserves many farmhouses that at their core have a converted longhouse. In Scotland, the change to better quality housing came only in the second half of the eighteenth century in the Lowlands, and the nineteenth century in the Highlands. In the Outer Hebrides, traditional ‘black houses’, typified by the surviving one at Arnol in Lewis, were occupied as late as the 1960s. Excavation is especially important in areas like northern England and Scotland, where housing standards were poorer and ordinary domestic buildings from the sixteenth, seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries have virtually disappeared from the landscape. With the end of private warfare under the growing power of the Tudor state, country mansions began to replace medieval baronial castles. Excavation has played little part in the study of the evolution of English country houses, apart from vanished royal palaces like Nonsuch, Surrey, but, as with churches, there is much scope for the detailed survey of surviving structures. The shake-up in landholding with the Dissolution of the monasteries provided many gentry families with additional land and income. In some cases, the domestic buildings of monasteries were converted to secular uses; elsewhere they provided useful quarries for building stone. The country house and its surrounding parklands, emphasizing the control of great landowners over the

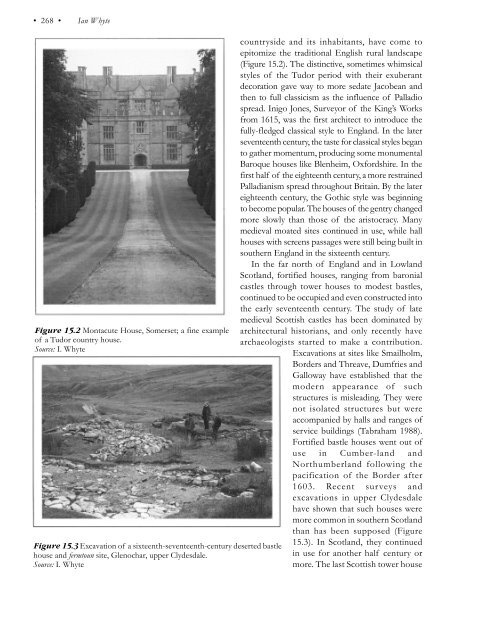

• 268 • Ian Whyte Figure 15.2 Montacute House, Somerset; a fine example of a Tudor country house. Source: I. Whyte Figure 15.3 Excavation of a sixteenth-seventeenth-century deserted bastle house and fermtoun site, Glenochar, upper Clydesdale. Source: I. Whyte countryside and its inhabitants, have come to epitomize the traditional English rural landscape (Figure 15.2). The distinctive, sometimes whimsical styles of the Tudor period with their exuberant decoration gave way to more sedate Jacobean and then to full classicism as the influence of Palladio spread. Inigo Jones, Surveyor of the King’s Works from 1615, was the first architect to introduce the fully-fledged classical style to England. In the later seventeenth century, the taste for classical styles began to gather momentum, producing some monumental Baroque houses like Blenheim, Oxfordshire. In the first half of the eighteenth century, a more restrained Palladianism spread throughout Britain. By the later eighteenth century, the Gothic style was beginning to become popular. The houses of the gentry changed more slowly than those of the aristocracy. Many medieval moated sites continued in use, while hall houses with screens passages were still being built in southern England in the sixteenth century. In the far north of England and in Lowland Scotland, fortified houses, ranging from baronial castles through tower houses to modest bastles, continued to be occupied and even constructed into the early seventeenth century. The study of late medieval Scottish castles has been dominated by architectural historians, and only recently have archaeologists started to make a contribution. Excavations at sites like Smailholm, Borders and Threave, Dumfries and Galloway have established that the modern appearance of such structures is misleading. They were not isolated structures but were accompanied by halls and ranges of service buildings (Tabraham 1988). Fortified bastle houses went out of use in Cumber-land and Northumberland following the pacification of the Border after 1603. Recent surveys and excavations in upper Clydesdale have shown that such houses were more common in southern Scotland than has been supposed (Figure 15.3). In Scotland, they continued in use for another half century or more. The last Scottish tower house

- Page 231 and 232: • 216 • John Schofield Suburbs

- Page 233 and 234: • 218 • John Schofield archaeol

- Page 235 and 236: • 220 • John Schofield continuo

- Page 237 and 238: • 222 • John Schofield environm

- Page 239 and 240: • 224 • John Schofield particul

- Page 241 and 242: • 226 • John Schofield phenomen

- Page 243 and 244: Chapter Thirteen Landscapes of the

- Page 245 and 246: • 230 • Roberta Gilchrist until

- Page 247 and 248: • 232 • Roberta Gilchrist multi

- Page 249 and 250: • 234 • Roberta Gilchrist house

- Page 251 and 252: • 236 • Roberta Gilchrist Figur

- Page 253 and 254: • 238 • Roberta Gilchrist Welsh

- Page 255 and 256: • 240 • Roberta Gilchrist The a

- Page 257 and 258: • 242 • Roberta Gilchrist refer

- Page 259 and 260: • 244 • Roberta Gilchrist bowl,

- Page 261 and 262: • 246 • Roberta Gilchrist Aston

- Page 263 and 264: • 248 • Paul Stamper peasants.

- Page 265 and 266: • 250 • Paul Stamper The first

- Page 267 and 268: • 252 • Paul Stamper Astill 198

- Page 269 and 270: • 254 • Paul Stamper Figure 14.

- Page 271 and 272: • 256 • Paul Stamper carpenters

- Page 273 and 274: • 258 • Paul Stamper ‘open’

- Page 275 and 276: • 260 • Paul Stamper replanning

- Page 277 and 278: • 262 • Paul Stamper projects (

- Page 279 and 280: Chapter Fifteen The historical geog

- Page 281: • 266 • Ian Whyte villages—te

- Page 285 and 286: • 270 • Ian Whyte LANDSCAPE App

- Page 287 and 288: • 272 • Ian Whyte gardens had b

- Page 289 and 290: • 274 • Ian Whyte The need of i

- Page 291 and 292: • 276 • Ian Whyte TOWNSCAPES Ur

- Page 293 and 294: • 278 • Ian Whyte Buxton, Derby

- Page 295 and 296: Chapter Sixteen The workshop of the

- Page 297 and 298: • 282 • Kate Clark writing duri

- Page 299 and 300: • 284 • Kate Clark Industrial a

- Page 301 and 302: • 286 • Kate Clark Archaeologic

- Page 303 and 304: • 288 • Kate Clark nevertheless

- Page 305 and 306: • 290 • Kate Clark production t

- Page 307 and 308: • 292 • Kate Clark Some rivers

- Page 309 and 310: • 294 • Kate Clark however, can

- Page 311 and 312: • 296 • Kate Clark have the maj

- Page 313 and 314: • 298 • Timothy Darvill never p

- Page 315 and 316: • 300 • Timothy Darvill What un

- Page 317 and 318: • 302 • Timothy Darvill authori

- Page 319 and 320: • 304 • Timothy Darvill methodo

- Page 321 and 322: • 306 • Timothy Darvill Develop

- Page 323 and 324: • 308 • Timothy Darvill • Ass

- Page 325 and 326: • 310 • Timothy Darvill cause t

- Page 327 and 328: • 312 • Timothy Darvill Archaeo

- Page 329 and 330: • 314 • Timothy Darvill its fut

- Page 331 and 332: Index Illustrations are indicated b

• 268 • Ian Whyte<br />

Figure 15.2 Montacute House, Somerset; a fine example<br />

<strong>of</strong> a Tudor country house.<br />

Source: I. Whyte<br />

Figure 15.3 Ex<strong>ca</strong>vation <strong>of</strong> a sixteenth-seventeenth-century deserted bastle<br />

house and fermtoun site, Glenochar, upper Clydesdale.<br />

Source: I. Whyte<br />

countryside and its inhabitants, have come to<br />

epitomize the traditional English rural lands<strong>ca</strong>pe<br />

(Figure 15.2). <strong>The</strong> distinctive, sometimes whimsi<strong>ca</strong>l<br />

styles <strong>of</strong> the Tudor period with their exuberant<br />

decoration gave way to more sedate Jacobean and<br />

then to full classicism as the influence <strong>of</strong> Palladio<br />

spread. Inigo Jones, Surveyor <strong>of</strong> the King’s Works<br />

<strong>from</strong> 1615, was the first architect to introduce the<br />

fully-fledged classi<strong>ca</strong>l style to England. In the later<br />

seventeenth century, the taste for classi<strong>ca</strong>l styles began<br />

to gather momentum, producing some monumental<br />

Baroque houses like Blenheim, Oxfordshire. In the<br />

first half <strong>of</strong> the eighteenth century, a more restrained<br />

Palladianism spread throughout <strong>Britain</strong>. By the later<br />

eighteenth century, the Gothic style was beginning<br />

to become popular. <strong>The</strong> houses <strong>of</strong> the gentry changed<br />

more slowly than those <strong>of</strong> the aristocracy. Many<br />

medieval moated sites continued in use, while hall<br />

houses with screens passages were still being built in<br />

southern England in the sixteenth century.<br />

In the far north <strong>of</strong> England and in Lowland<br />

Scotland, fortified houses, ranging <strong>from</strong> baronial<br />

<strong>ca</strong>stles through tower houses to modest bastles,<br />

continued to be occupied and even constructed into<br />

the early seventeenth century. <strong>The</strong> study <strong>of</strong> late<br />

medieval Scottish <strong>ca</strong>stles has been dominated by<br />

architectural historians, and only recently have<br />

archaeologists started to make a contribution.<br />

Ex<strong>ca</strong>vations at sites like Smailholm,<br />

Borders and Threave, Dumfries and<br />

Galloway have established that the<br />

modern appearance <strong>of</strong> such<br />

structures is misleading. <strong>The</strong>y were<br />

not isolated structures but were<br />

accompanied by halls and ranges <strong>of</strong><br />

service buildings (Tabraham 1988).<br />

Fortified bastle houses went out <strong>of</strong><br />

use in Cumber-land and<br />

Northumberland following the<br />

pacifi<strong>ca</strong>tion <strong>of</strong> the Border after<br />

1603. Recent surveys and<br />

ex<strong>ca</strong>vations in upper Clydesdale<br />

have shown that such houses were<br />

more common in southern Scotland<br />

than has been supposed (Figure<br />

15.3). In Scotland, they continued<br />

in use for another half century or<br />

more. <strong>The</strong> last Scottish tower house