The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

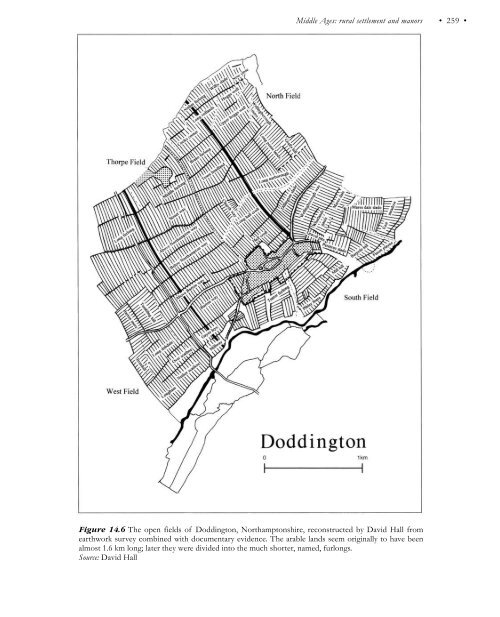

Middle Ages: rural settlement and manors • 259 • Figure 14.6 The open fields of Doddington, Northamptonshire, reconstructed by David Hall from earthwork survey combined with documentary evidence. The arable lands seem originally to have been almost 1.6 km long; later they were divided into the much shorter, named, furlongs. Source: David Hall

• 260 • Paul Stamper replanning: the imposition in the first half of the tenth century of a new local administrative organization following the reconquest of the Danelaw by Wessex. This established the hundred as the standard local unit of administration and the hide, nominally 48 ha, as the basic unit on which fiscal and military obligations were based. Newly divided up, the landscape then became ‘a record in itself of dues; a regional imposition for national administrative purposes’. This revelation of a great replanning of the countryside in the late Saxon period, at least equal to that which followed the enclosures of a millennium later, is one of the great discoveries of British archaeology of the later twentieth century. Just as methodological advances have led to a better understanding of the lowland agricultural landscapes of the Middle Ages, so they are likewise beginning to unravel the stone walled countryside of upland areas. At Roystone Grange, in the White Peak of Derbyshire, a multiperiod landscape criss-crossed with dry stone walls of various prehistoric to post-medieval dates, careful examination of wall types, and of their relationship to each other and to dated features and sites, has allowed the reconstruction of the local countryside at different times. One phase of walling, for instance, seems to relate to the establishment of a Cistercian grange—a monastic farm—at Roystone in the later twelfth century, while a later one apparently dates from the enclosure of the moorland c.1600 (Hodges 1991, ch. 2). Similarly, work in the Lakeland valleys for the National Trust has been equally successful in identifying several phases of walling, which has in turn led to the ascription of functions to the different zones of field. The most significant type of wall, the head dykes or ring garths that run continuously along the valleys, separating the cultivated land from the rough pastures above, is now seen as having been established here in the eleventh or twelfth century. INDUSTRY Over the last generation, a much better understanding of medieval industry has been arrived at, largely through the application of what may broadly be termed archaeological techniques, including, alongside excavation, the study of industrial landscapes and the scientific and technical studies of objects, by-products and residues (Blair and Ramsay 1991). With the iron industry, for instance (Geddes 1991), it can now be seen that by the twelfth century ore was having to be got via tunnels, trenches and bell pits, presumably because the easily available surface deposits had been worked out. While there were few changes in smelting techniques between the Romano-British period and the late Middle Ages, blast furnaces were introduced from abroad in the late fifteenth century. Newbridge, Sussex, is the earliest known; Henry VIII commissioned cast-iron ordnance from here in 1496, and within a short time the product range included domestic items such as firedogs, fire backs and tomb slabs. Water-powered forges, where a water wheel was used to drive bellows and hammers, appeared earlier, the first example being set up at Chingley, Kent, in the early fourteenth century. Archaeology has also shown, in excavations at Bordesley Abbey, Worcestershire, how water power was harnessed from the late twelfth century to provide power in a smithy housed in a mill equipped with wooden cogs and stone bearings (Astill 1993). While relatively few smithies have yet been excavated, the microscopic analysis of slags and hammer scales seems likely to enable a far fuller understanding both of the spatial organization within individual complexes and of the techniques employed there. The gradual advances in iron-working technologies were reflected in the ever-broader range of iron and steel goods manufactured, some advances at least being demand-led. The clergy, for instance, needed accurate time-keeping devices, and between 1280 and 1300 iron horologia begin to be mentioned; the earliest surviving example is that of 1386 in Salisbury Cathedral (Geddes 1991, 178–179).

- Page 223 and 224: • 208 • Julian D.Richards stage

- Page 225 and 226: Chapter Twelve Landscapes of the Mi

- Page 227 and 228: • 212 • John Schofield Other to

- Page 229 and 230: • 214 • John Schofield A second

- Page 231 and 232: • 216 • John Schofield Suburbs

- Page 233 and 234: • 218 • John Schofield archaeol

- Page 235 and 236: • 220 • John Schofield continuo

- Page 237 and 238: • 222 • John Schofield environm

- Page 239 and 240: • 224 • John Schofield particul

- Page 241 and 242: • 226 • John Schofield phenomen

- Page 243 and 244: Chapter Thirteen Landscapes of the

- Page 245 and 246: • 230 • Roberta Gilchrist until

- Page 247 and 248: • 232 • Roberta Gilchrist multi

- Page 249 and 250: • 234 • Roberta Gilchrist house

- Page 251 and 252: • 236 • Roberta Gilchrist Figur

- Page 253 and 254: • 238 • Roberta Gilchrist Welsh

- Page 255 and 256: • 240 • Roberta Gilchrist The a

- Page 257 and 258: • 242 • Roberta Gilchrist refer

- Page 259 and 260: • 244 • Roberta Gilchrist bowl,

- Page 261 and 262: • 246 • Roberta Gilchrist Aston

- Page 263 and 264: • 248 • Paul Stamper peasants.

- Page 265 and 266: • 250 • Paul Stamper The first

- Page 267 and 268: • 252 • Paul Stamper Astill 198

- Page 269 and 270: • 254 • Paul Stamper Figure 14.

- Page 271 and 272: • 256 • Paul Stamper carpenters

- Page 273: • 258 • Paul Stamper ‘open’

- Page 277 and 278: • 262 • Paul Stamper projects (

- Page 279 and 280: Chapter Fifteen The historical geog

- Page 281 and 282: • 266 • Ian Whyte villages—te

- Page 283 and 284: • 268 • Ian Whyte Figure 15.2 M

- Page 285 and 286: • 270 • Ian Whyte LANDSCAPE App

- Page 287 and 288: • 272 • Ian Whyte gardens had b

- Page 289 and 290: • 274 • Ian Whyte The need of i

- Page 291 and 292: • 276 • Ian Whyte TOWNSCAPES Ur

- Page 293 and 294: • 278 • Ian Whyte Buxton, Derby

- Page 295 and 296: Chapter Sixteen The workshop of the

- Page 297 and 298: • 282 • Kate Clark writing duri

- Page 299 and 300: • 284 • Kate Clark Industrial a

- Page 301 and 302: • 286 • Kate Clark Archaeologic

- Page 303 and 304: • 288 • Kate Clark nevertheless

- Page 305 and 306: • 290 • Kate Clark production t

- Page 307 and 308: • 292 • Kate Clark Some rivers

- Page 309 and 310: • 294 • Kate Clark however, can

- Page 311 and 312: • 296 • Kate Clark have the maj

- Page 313 and 314: • 298 • Timothy Darvill never p

- Page 315 and 316: • 300 • Timothy Darvill What un

- Page 317 and 318: • 302 • Timothy Darvill authori

- Page 319 and 320: • 304 • Timothy Darvill methodo

- Page 321 and 322: • 306 • Timothy Darvill Develop

- Page 323 and 324: • 308 • Timothy Darvill • Ass

Middle Ages: rural settlement and manors<br />

• 259 •<br />

Figure 14.6 <strong>The</strong> open fields <strong>of</strong> Doddington, Northamptonshire, reconstructed by David Hall <strong>from</strong><br />

earthwork survey combined with documentary evidence. <strong>The</strong> arable lands seem originally to have been<br />

almost 1.6 km long; later they were divided into the much shorter, named, furlongs.<br />

Source: David Hall