The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

Middle Ages: churches, castles and monasteries • 235 • thirteenth century, a castle might contain several different halls, each the focus of an individual household, in addition to the great hall, which was the centre of ceremonial and administrative life. Freestanding halls were generally located at the ground-floor level, open to the roof, sometimes with an associated two-storey chamber block to provide private chambers (e.g. Boothby Pagnell, Lincolnshire). Upper halls, located at first-floor level, were common in twelfth-century towerkeeps and proto-keeps (such as Chepstow, Gwent), and again in the fourteenth to fifteenth centuries, as at Nunney, Somerset (Thompson 1995). Excavation has improved our understanding of the technology of castle construction. Traces of temporary workshops were uncovered at Sandal, West Yorkshire, and Portchester, Hampshire, the latter consisting of two lead-melting hearths set into the floor of a hall, with a temporary smithy erected in a courtyard. At Sandal, the conversion of the castle from timber to masonry required lead- and iron-working hearths and horse- and oxen-drawn carts to move supplies; tracks from these vehicles were traced during the excavations (Mayes and Butler 1983). Lime kilns are commonly found at castles, ranging from basic pits to stone-built kilns, such as a thirteenth-century example at Bedford. A kiln for the production of ridge-tiles, c.1240, was excavated at Sandal, and additional evidence for roof furniture included tiles, slates and finials. Lead and stone tiles were also commonly used for roofing materials. Worked stone and fragments of decorated wall plaster have been recovered from excavated castles, together with window glass, although this was not common in non-royal castles until the later thirteenth century (Kenyon 1990, 164–167). Along the coasts of Britain, naturally defensible sites were used for castle building, such as Corfe, Dorset. The earliest castles sometimes reused Roman forts and Saxon burhs, in order to take advantage of ready-made defences and good networks of roads. Royal castles were predominantly urban, associated with towns in order to dominate the largest concentrations of population, and to ease the administration of a newly conquered land. The Norman barons held scattered parcels of land, rather than consolidated estates, and would build their castles at the centre of a concentration of lands, sited to take into account the availability of water, good communications and arable resources (Pounds 1990). Barnard Castle, Co. Durham, was sited on the boundary between woodland and grazing land, and its estate held a balanced range of land types and resources (Austin 1984). It was common to enhance the symbolism of lordship by twinning castles with parish churches or monasteries, especially Benedictine and Cluniac houses. Economic development was maximized by the Normans through foundations of new towns: up to one third of these grew up at the gates of castles. Grid-iron street plans developed at planned castle towns such as Castle Acre and New Buckenham, Norfolk. Two major types of earthwork castles were constructed in Norman Britain: the motte and bailey, and the ringwork. The motte and bailey outnumbered the ringwork by as much as four to one; it was built during the first century after the Conquest and during the civil war between King Stephen and Queen Matilda (1138–53). The motte was an artificial mound of earth, surrounded by a ditch, and frequently associated with one or more baileys, which were enclosures surrounded by earthen banks. A timber tower was placed within or on top of the motte. Recent excavations have shown that the tower was sometimes the primary feature, with the motte formed around it by heaping up earth from the encircling ditch. This method of construction is shown on the Bayeux Tapestry and has been confirmed by excavations at South Mimms, Hertfordshire, where a wooden tower 35m square was set on a flint footing and surrounded by a motte with a low flint wall around its base. Entrance to the tower was gained via a tunnel through the motte, and the motte was revetted with timber shuttering. The ringwork castle, in contrast, was a simple enclosure comprising a bank and ditch. In some cases, ringworks were filled in with later mottes, as at Aldingham, Cumbria, while at Goltho a motte was levelled in the twelfth century to serve as a raised platform for an aisled hall and domestic buildings (Beresford 1987). Timber buildings

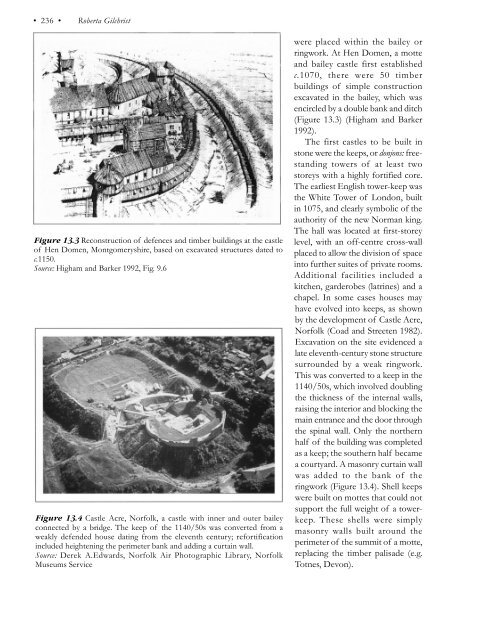

• 236 • Roberta Gilchrist Figure 13.3 Reconstruction of defences and timber buildings at the castle of Hen Domen, Montgomeryshire, based on excavated structures dated to c.1150. Source: Higham and Barker 1992, Fig. 9.6 Figure 13.4 Castle Acre, Norfolk, a castle with inner and outer bailey connected by a bridge. The keep of the 1140/50s was converted from a weakly defended house dating from the eleventh century; refortification included heightening the perimeter bank and adding a curtain wall. Source: Derek A.Edwards, Norfolk Air Photographic Library, Norfolk Museums Service were placed within the bailey or ringwork. At Hen Domen, a motte and bailey castle first established c.1070, there were 50 timber buildings of simple construction excavated in the bailey, which was encircled by a double bank and ditch (Figure 13.3) (Higham and Barker 1992). The first castles to be built in stone were the keeps, or donjons: freestanding towers of at least two storeys with a highly fortified core. The earliest English tower-keep was the White Tower of London, built in 1075, and clearly symbolic of the authority of the new Norman king. The hall was located at first-storey level, with an off-centre cross-wall placed to allow the division of space into further suites of private rooms. Additional facilities included a kitchen, garderobes (latrines) and a chapel. In some cases houses may have evolved into keeps, as shown by the development of Castle Acre, Norfolk (Coad and Streeten 1982). Excavation on the site evidenced a late eleventh-century stone structure surrounded by a weak ringwork. This was converted to a keep in the 1140/50s, which involved doubling the thickness of the internal walls, raising the interior and blocking the main entrance and the door through the spinal wall. Only the northern half of the building was completed as a keep; the southern half became a courtyard. A masonry curtain wall was added to the bank of the ringwork (Figure 13.4). Shell keeps were built on mottes that could not support the full weight of a towerkeep. These shells were simply masonry walls built around the perimeter of the summit of a motte, replacing the timber palisade (e.g. Totnes, Devon).

- Page 199 and 200: • 184 • Catherine Hills but the

- Page 201 and 202: • 186 • Catherine Hills Attenti

- Page 203 and 204: • 188 • Catherine Hills are har

- Page 205 and 206: • 190 • Catherine Hills grave a

- Page 207 and 208: • 192 • Catherine Hills Figure

- Page 209 and 210: Chapter Eleven The Scandinavian pre

- Page 211 and 212: • 196 • Julian D.Richards There

- Page 213 and 214: • 198 • Julian D.Richards the A

- Page 215 and 216: • 200 • Julian D.Richards and a

- Page 217 and 218: • 202 • Julian D.Richards by an

- Page 219 and 220: • 204 • Julian D.Richards Figur

- Page 221 and 222: • 206 • Julian D.Richards avail

- Page 223 and 224: • 208 • Julian D.Richards stage

- Page 225 and 226: Chapter Twelve Landscapes of the Mi

- Page 227 and 228: • 212 • John Schofield Other to

- Page 229 and 230: • 214 • John Schofield A second

- Page 231 and 232: • 216 • John Schofield Suburbs

- Page 233 and 234: • 218 • John Schofield archaeol

- Page 235 and 236: • 220 • John Schofield continuo

- Page 237 and 238: • 222 • John Schofield environm

- Page 239 and 240: • 224 • John Schofield particul

- Page 241 and 242: • 226 • John Schofield phenomen

- Page 243 and 244: Chapter Thirteen Landscapes of the

- Page 245 and 246: • 230 • Roberta Gilchrist until

- Page 247 and 248: • 232 • Roberta Gilchrist multi

- Page 249: • 234 • Roberta Gilchrist house

- Page 253 and 254: • 238 • Roberta Gilchrist Welsh

- Page 255 and 256: • 240 • Roberta Gilchrist The a

- Page 257 and 258: • 242 • Roberta Gilchrist refer

- Page 259 and 260: • 244 • Roberta Gilchrist bowl,

- Page 261 and 262: • 246 • Roberta Gilchrist Aston

- Page 263 and 264: • 248 • Paul Stamper peasants.

- Page 265 and 266: • 250 • Paul Stamper The first

- Page 267 and 268: • 252 • Paul Stamper Astill 198

- Page 269 and 270: • 254 • Paul Stamper Figure 14.

- Page 271 and 272: • 256 • Paul Stamper carpenters

- Page 273 and 274: • 258 • Paul Stamper ‘open’

- Page 275 and 276: • 260 • Paul Stamper replanning

- Page 277 and 278: • 262 • Paul Stamper projects (

- Page 279 and 280: Chapter Fifteen The historical geog

- Page 281 and 282: • 266 • Ian Whyte villages—te

- Page 283 and 284: • 268 • Ian Whyte Figure 15.2 M

- Page 285 and 286: • 270 • Ian Whyte LANDSCAPE App

- Page 287 and 288: • 272 • Ian Whyte gardens had b

- Page 289 and 290: • 274 • Ian Whyte The need of i

- Page 291 and 292: • 276 • Ian Whyte TOWNSCAPES Ur

- Page 293 and 294: • 278 • Ian Whyte Buxton, Derby

- Page 295 and 296: Chapter Sixteen The workshop of the

- Page 297 and 298: • 282 • Kate Clark writing duri

- Page 299 and 300: • 284 • Kate Clark Industrial a

• 236 • Roberta Gilchrist<br />

Figure 13.3 Reconstruction <strong>of</strong> defences and timber buildings at the <strong>ca</strong>stle<br />

<strong>of</strong> Hen Domen, Montgomeryshire, based on ex<strong>ca</strong>vated structures dated to<br />

c.1150.<br />

Source: Higham and Barker 1992, Fig. 9.6<br />

Figure 13.4 Castle Acre, Norfolk, a <strong>ca</strong>stle with inner and outer bailey<br />

connected by a bridge. <strong>The</strong> keep <strong>of</strong> the 1140/50s was converted <strong>from</strong> a<br />

weakly defended house dating <strong>from</strong> the eleventh century; refortifi<strong>ca</strong>tion<br />

included heightening the perimeter bank and adding a curtain wall.<br />

Source: Derek A.Edwards, Norfolk Air Photographic Library, Norfolk<br />

Museums Service<br />

were placed within the bailey or<br />

ringwork. At Hen Domen, a motte<br />

and bailey <strong>ca</strong>stle first established<br />

c.1070, there were 50 timber<br />

buildings <strong>of</strong> simple construction<br />

ex<strong>ca</strong>vated in the bailey, which was<br />

encircled by a double bank and ditch<br />

(Figure 13.3) (Higham and Barker<br />

1992).<br />

<strong>The</strong> first <strong>ca</strong>stles to be built in<br />

stone were the keeps, or donjons: freestanding<br />

towers <strong>of</strong> at least two<br />

storeys with a highly fortified core.<br />

<strong>The</strong> earliest English tower-keep was<br />

the White Tower <strong>of</strong> London, built<br />

in 1075, and clearly symbolic <strong>of</strong> the<br />

authority <strong>of</strong> the new Norman king.<br />

<strong>The</strong> hall was lo<strong>ca</strong>ted at first-storey<br />

level, with an <strong>of</strong>f-centre cross-wall<br />

placed to allow the division <strong>of</strong> space<br />

into further suites <strong>of</strong> private rooms.<br />

Additional facilities included a<br />

kitchen, garderobes (latrines) and a<br />

chapel. In some <strong>ca</strong>ses houses may<br />

have evolved into keeps, as shown<br />

by the development <strong>of</strong> Castle Acre,<br />

Norfolk (Coad and Streeten 1982).<br />

Ex<strong>ca</strong>vation on the site evidenced a<br />

late eleventh-century stone structure<br />

surrounded by a weak ringwork.<br />

This was converted to a keep in the<br />

1140/50s, which involved doubling<br />

the thickness <strong>of</strong> the internal walls,<br />

raising the interior and blocking the<br />

main entrance and the door through<br />

the spinal wall. Only the northern<br />

half <strong>of</strong> the building was completed<br />

as a keep; the southern half be<strong>ca</strong>me<br />

a courtyard. A masonry curtain wall<br />

was added to the bank <strong>of</strong> the<br />

ringwork (Figure 13.4). Shell keeps<br />

were built on mottes that could not<br />

support the full weight <strong>of</strong> a towerkeep.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se shells were simply<br />

masonry walls built around the<br />

perimeter <strong>of</strong> the summit <strong>of</strong> a motte,<br />

replacing the timber palisade (e.g.<br />

Totnes, Devon).