The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

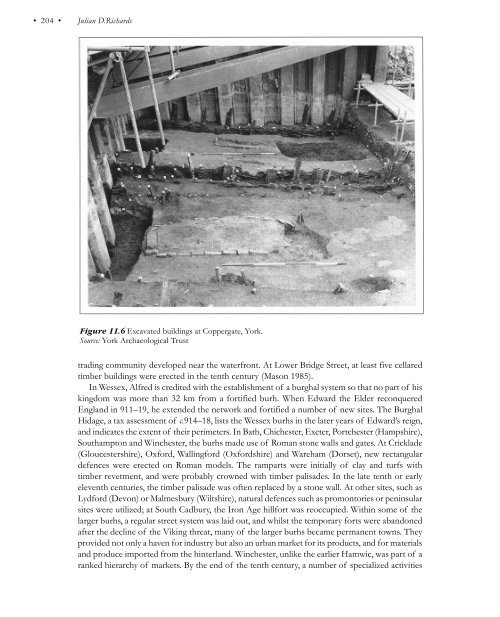

The Scandinavian presence • 203 • Towns In northern and western Britain, there are no towns during this period, but in England the Scandinavian presence coincided with a period of urban growth. In the East Midlands there are five towns, Derby, Leicester, Lincoln, Nottingham and Stamford, which are described in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle as Five Boroughs; they were once thought to have been specially fortified towns, established by the Danes after the partition of the Danelaw, and used by Alfred as a model for the burhs (below). However, they may not have become Danish strongholds until later, in which case they may have been modelled upon Alfred’s foundations, rather than the other way round (Hall 1989). There had been urban trading and manufacturing centres in England since the early eighth century. Sites such as Hamwic (Saxon Southampton), Eoforwic (York) and Lundenwic (London) developed under royal patronage around a waterfront where traders could beach their vessels and perhaps establish their booths in regulated plots. At most wic sites, however, the threat of attack in the Viking Age led the traders to seek protection within walled towns, and may also have disrupted trade. The site of Hamwic was depopulated by the late ninth century and the focus of tenth-century occupation shifted to higher ground within the area that was to become the medieval walled town. In London, the exposed waterfront site along the Strand was abandoned and the area of the old Roman fortress was reoccupied in the tenth century, becoming known as Lundenburh (Vince 1990). In York, a single coin of the 860s is the latest find from the Fishergate site, outside the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss, whilst activity commences in Coppergate at about this time. It is impossible to say, however, whether this starts before the Viking capture of York in 866 as a result of people seeking the protection of the walled town, or whether it is a consequence of the Viking settlement. It does appear that York’s Viking rulers renovated its Roman defences and remodelled its street system. They constructed a new bridge across the Ouse and built houses along Micklegate, ‘the great street’, leading to the new crossing point. In Coppergate, excavations between 1976 and 1981 of an area of deep, oxygen-free organic soils have provided some of the best preserved evidence of Viking Age urban life in the Danelaw. The Viking Age street was established by 930, and possibly as early as 900, with the delineation of four tenements, each 5.5 m wide. Initially, a single line of buildings was constructed along the street frontage, narrow end facing the street (Figure 11.6). These first buildings comprised timber wall posts and roof supports with wattlework wall panels. Each was about 4.4 m wide and 8.2 m or more in length. They had central clay hearths that would have provided both heat and light. There were probably doors at the front and rear of the properties, but windows are unlikely. In some cases, traces of wall benches were preserved. The finds suggest that these buildings served both as houses and workshops. In the late tenth century they were pulled down and replaced by substantial semi-basement structures with planked walls. Given that this occurred simultaneously along the street suggests that the tenements were under the control of a single landlord. The new buildings were probably two-storey structures with living accommodation above and extra storage and workshop space below (Hall 1994). The York examples are the best preserved in the British Isles, but cellared buildings also occur in other major towns such as London, Chester, Oxford and Thetford. They seem to be a response to the increased pressure upon urban space and the need to store goods in transit and stock-in-trade. Although some of the largest towns developed as trading sites, a much larger group of towns was established as defended forts or burhs, probably as a direct response to the Viking threat. The earliest examples were founded in Mercia c.780–90 by King Offa, possibly copying Carolingian practice. At Tamworth and Hereford, ramparts were erected to enclose a rectilinear area with one side protected by the river. At Chester, the surviving walls of the Roman fort were refurbished and probably extended down to the River Dee by Ethelflaed in 907. A substantial Hiberno-Norse

• 204 • Julian D.Richards Figure 11.6 Excavated buildings at Coppergate, York. Source: York Archaeological Trust trading community developed near the waterfront. At Lower Bridge Street, at least five cellared timber buildings were erected in the tenth century (Mason 1985). In Wessex, Alfred is credited with the establishment of a burghal system so that no part of his kingdom was more than 32 km from a fortified burh. When Edward the Elder reconquered England in 911–19, he extended the network and fortified a number of new sites. The Burghal Hidage, a tax assessment of c.914–18, lists the Wessex burhs in the later years of Edward’s reign, and indicates the extent of their perimeters. In Bath, Chichester, Exeter, Portchester (Hampshire), Southampton and Winchester, the burhs made use of Roman stone walls and gates. At Cricklade (Gloucestershire), Oxford, Wallingford (Oxfordshire) and Wareham (Dorset), new rectangular defences were erected on Roman models. The ramparts were initially of clay and turfs with timber revetment, and were probably crowned with timber palisades. In the late tenth or early eleventh centuries, the timber palisade was often replaced by a stone wall. At other sites, such as Lydford (Devon) or Malmesbury (Wiltshire), natural defences such as promontories or peninsular sites were utilized; at South Cadbury, the Iron Age hillfort was reoccupied. Within some of the larger burhs, a regular street system was laid out, and whilst the temporary forts were abandoned after the decline of the Viking threat, many of the larger burhs became permanent towns. They provided not only a haven for industry but also an urban market for its products, and for materials and produce imported from the hinterland. Winchester, unlike the earlier Hamwic, was part of a ranked hierarchy of markets. By the end of the tenth century, a number of specialized activities

- Page 167 and 168: • 152 • W.S.Hanson provision of

- Page 169 and 170: • 154 • W.S.Hanson Figure 8.11

- Page 171 and 172: • 156 • W.S.Hanson Bibliography

- Page 173 and 174: • 158 • Simon Esmonde Cleary th

- Page 175 and 176: • 160 • Simon Esmonde Cleary pe

- Page 177 and 178: • 162 • Simon Esmonde Cleary Fi

- Page 179 and 180: • 164 • Simon Esmonde Cleary li

- Page 181 and 182: • 166 • Simon Esmonde Cleary Ot

- Page 183 and 184: • 168 • Simon Esmonde Cleary si

- Page 185 and 186: • 170 • Simon Esmonde Cleary ra

- Page 187 and 188: • 172 • Simon Esmonde Cleary si

- Page 189 and 190: • 174 • Simon Esmonde Cleary th

- Page 191 and 192: Chapter Ten Early Historic Britain

- Page 193 and 194: • 178 • Catherine Hills retrosp

- Page 195 and 196: • 180 • Catherine Hills and the

- Page 197 and 198: • 182 • Catherine Hills Early m

- Page 199 and 200: • 184 • Catherine Hills but the

- Page 201 and 202: • 186 • Catherine Hills Attenti

- Page 203 and 204: • 188 • Catherine Hills are har

- Page 205 and 206: • 190 • Catherine Hills grave a

- Page 207 and 208: • 192 • Catherine Hills Figure

- Page 209 and 210: Chapter Eleven The Scandinavian pre

- Page 211 and 212: • 196 • Julian D.Richards There

- Page 213 and 214: • 198 • Julian D.Richards the A

- Page 215 and 216: • 200 • Julian D.Richards and a

- Page 217: • 202 • Julian D.Richards by an

- Page 221 and 222: • 206 • Julian D.Richards avail

- Page 223 and 224: • 208 • Julian D.Richards stage

- Page 225 and 226: Chapter Twelve Landscapes of the Mi

- Page 227 and 228: • 212 • John Schofield Other to

- Page 229 and 230: • 214 • John Schofield A second

- Page 231 and 232: • 216 • John Schofield Suburbs

- Page 233 and 234: • 218 • John Schofield archaeol

- Page 235 and 236: • 220 • John Schofield continuo

- Page 237 and 238: • 222 • John Schofield environm

- Page 239 and 240: • 224 • John Schofield particul

- Page 241 and 242: • 226 • John Schofield phenomen

- Page 243 and 244: Chapter Thirteen Landscapes of the

- Page 245 and 246: • 230 • Roberta Gilchrist until

- Page 247 and 248: • 232 • Roberta Gilchrist multi

- Page 249 and 250: • 234 • Roberta Gilchrist house

- Page 251 and 252: • 236 • Roberta Gilchrist Figur

- Page 253 and 254: • 238 • Roberta Gilchrist Welsh

- Page 255 and 256: • 240 • Roberta Gilchrist The a

- Page 257 and 258: • 242 • Roberta Gilchrist refer

- Page 259 and 260: • 244 • Roberta Gilchrist bowl,

- Page 261 and 262: • 246 • Roberta Gilchrist Aston

- Page 263 and 264: • 248 • Paul Stamper peasants.

- Page 265 and 266: • 250 • Paul Stamper The first

- Page 267 and 268: • 252 • Paul Stamper Astill 198

• 204 • Julian D.Richards<br />

Figure 11.6 Ex<strong>ca</strong>vated buildings at Coppergate, York.<br />

Source: York Archaeologi<strong>ca</strong>l Trust<br />

trading community developed near the waterfront. At Lower Bridge Street, at least five cellared<br />

timber buildings were erected in the tenth century (Mason 1985).<br />

In Wessex, Alfred is credited with the establishment <strong>of</strong> a burghal system so that no part <strong>of</strong> his<br />

kingdom was more than 32 km <strong>from</strong> a fortified burh. When Edward the Elder reconquered<br />

England in 911–19, he extended the network and fortified a number <strong>of</strong> new sites. <strong>The</strong> Burghal<br />

Hidage, a tax assessment <strong>of</strong> c.914–18, lists the Wessex burhs in the later years <strong>of</strong> Edward’s reign,<br />

and indi<strong>ca</strong>tes the extent <strong>of</strong> their perimeters. In Bath, Chichester, Exeter, Portchester (Hampshire),<br />

Southampton and Winchester, the burhs made use <strong>of</strong> Roman stone walls and gates. At Cricklade<br />

(Gloucestershire), Oxford, Wallingford (Oxfordshire) and Wareham (Dorset), new rectangular<br />

defences were erected on Roman models. <strong>The</strong> ramparts were initially <strong>of</strong> clay and turfs with<br />

timber revetment, and were probably crowned with timber palisades. In the late tenth or early<br />

eleventh centuries, the timber palisade was <strong>of</strong>ten replaced by a stone wall. At other sites, such as<br />

Lydford (Devon) or Malmesbury (Wiltshire), natural defences such as promontories or peninsular<br />

sites were utilized; at South Cadbury, the Iron Age hillfort was reoccupied. Within some <strong>of</strong> the<br />

larger burhs, a regular street system was laid out, and whilst the temporary forts were abandoned<br />

after the decline <strong>of</strong> the Viking threat, many <strong>of</strong> the larger burhs be<strong>ca</strong>me permanent towns. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

provided not only a haven for industry but also an urban market for its products, and for materials<br />

and produce imported <strong>from</strong> the hinterland. Winchester, unlike the earlier Hamwic, was part <strong>of</strong> a<br />

ranked hierarchy <strong>of</strong> markets. By the end <strong>of</strong> the tenth century, a number <strong>of</strong> specialized activities