The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

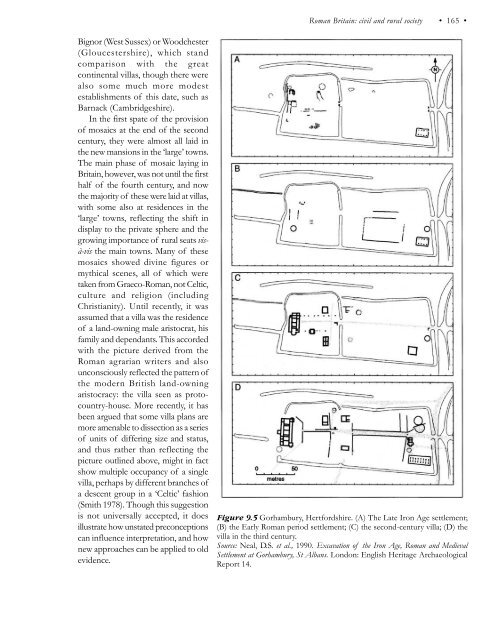

Roman Britain: civil and rural society • 165 • Bignor (West Sussex) or Woodchester (Gloucestershire), which stand comparison with the great continental villas, though there were also some much more modest establishments of this date, such as Barnack (Cambridgeshire). In the first spate of the provision of mosaics at the end of the second century, they were almost all laid in the new mansions in the ‘large’ towns. The main phase of mosaic laying in Britain, however, was not until the first half of the fourth century, and now the majority of these were laid at villas, with some also at residences in the ‘large’ towns, reflecting the shift in display to the private sphere and the growing importance of rural seats visà-vis the main towns. Many of these mosaics showed divine figures or mythical scenes, all of which were taken from Graeco-Roman, not Celtic, culture and religion (including Christianity). Until recently, it was assumed that a villa was the residence of a land-owning male aristocrat, his family and dependants. This accorded with the picture derived from the Roman agrarian writers and also unconsciously reflected the pattern of the modern British land-owning aristocracy: the villa seen as protocountry-house. More recently, it has been argued that some villa plans are more amenable to dissection as a series of units of differing size and status, and thus rather than reflecting the picture outlined above, might in fact show multiple occupancy of a single villa, perhaps by different branches of a descent group in a ‘Celtic’ fashion (Smith 1978). Though this suggestion is not universally accepted, it does illustrate how unstated preconceptions can influence interpretation, and how new approaches can be applied to old evidence. Figure 9.5 Gorhambury, Hertfordshire. (A) The Late Iron Age settlement; (B) the Early Roman period settlement; (C) the second-century villa; (D) the villa in the third century. Source: Neal, D.S. et al., 1990. Excavation of the Iron Age, Roman and Medieval Settlement at Gorhambury, St Albans. London: English Heritage Archaeological Report 14.

• 166 • Simon Esmonde Cleary Other rural settlements One of the many benefits of aerial and other survey techniques has been to end dependence on villas for our view of the Romano-British countryside and its society. Instead of a number of isolated sites, archaeologists can now discern a landscape articulated into fieldsystems, and crossed by tracks and boundaries (Fulford 1990). It is now clear that the great majority of settlements were of the ‘native farmstead’ type, that is enclosed groups of structures, usually of the prehistoric roundhouse tradition and yielding relatively little Romanized artefactual material (Hingley 1989). Alongside these dispersed, small settlements, perhaps the homes of extended family groups, there are also nucleated linear settlements, somewhat reminiscent of medieval village plans. These are best known in Somerset (Catsgore), Wiltshire (Chisenbury Warren, Nook) and Hampshire (Chalton) (Figure 9.6). Many non-villa settlements continue on the same site from the Late Iron Age, but there is increasing evidence Figure 9.6 Settlement and landscape of the Roman period in the vicinity that through the 400 years of Roman of Chalton, Hampshire. Britain, there was much settlement Source: Cunliffe, B.W., 1976, ‘A Romano-British village at Chalton, Hants’, shift, boundary redrawing and the Proceedings of the Hampshire Field Club 33. creation of new field-systems, so that the agrarian landscape of the fourth century would often have been markedly different from that of the first. Large-scale modern excavations in advance of gravel-extraction in the river valleys of lowland Britain at sites in the upper Thames Valley such as Claydon Pike, Lechlade (Gloucestershire), the Warwickshire Avon at Beckford (Hereford and Worcestershire) and Wasperton (Warwickshire) have enabled detailed studies of the shifting pattern of settlements within their contemporary landscapes. It can seem at first sight that the majority of the rural population was little touched by the Roman way of doing things, though archaeologists should not slide too easily into thinking that there was no contact. Towns ‘large’ and ‘small’ would make available new products and new ideas. Links up the social hierarchy to Romanized landowners would also introduce new ways. Moreover, the ubiquitous demands of taxation, military supply and possibly military service would make these people aware of the imperial system. Though in their day-to-day lives there might be little direct evidence of Rome, the social, economic and mental frameworks within which those lives were conducted would have changed.

- Page 129 and 130: • 114 • Colin Haselgrove votive

- Page 131 and 132: • 116 • Colin Haselgrove Figure

- Page 133 and 134: • 118 • Colin Haselgrove Figure

- Page 135 and 136: • 120 • Colin Haselgrove ancill

- Page 137 and 138: • 122 • Colin Haselgrove East A

- Page 139 and 140: • 124 • Colin Haselgrove France

- Page 141 and 142: • 126 • Colin Haselgrove As in

- Page 143 and 144: • 128 • Colin Haselgrove distri

- Page 145 and 146: • 130 • Colin Haselgrove From 1

- Page 147 and 148: • 132 • Colin Haselgrove throug

- Page 149 and 150: • 134 • Colin Haselgrove Stead,

- Page 151 and 152: • 136 • W.S.Hanson Table 8.1 Ev

- Page 153 and 154: • 138 • W.S.Hanson country are

- Page 155 and 156: • 140 • W.S.Hanson eventually s

- Page 157 and 158: • 142 • W.S.Hanson Figure 8.4 S

- Page 159 and 160: • 144 • W.S.Hanson Figure 8.5 S

- Page 161 and 162: • 146 • W.S.Hanson Westerton, P

- Page 163 and 164: • 148 • W.S.Hanson Figure 8.8 A

- Page 165 and 166: • 150 • W.S.Hanson around 1900,

- Page 167 and 168: • 152 • W.S.Hanson provision of

- Page 169 and 170: • 154 • W.S.Hanson Figure 8.11

- Page 171 and 172: • 156 • W.S.Hanson Bibliography

- Page 173 and 174: • 158 • Simon Esmonde Cleary th

- Page 175 and 176: • 160 • Simon Esmonde Cleary pe

- Page 177 and 178: • 162 • Simon Esmonde Cleary Fi

- Page 179: • 164 • Simon Esmonde Cleary li

- Page 183 and 184: • 168 • Simon Esmonde Cleary si

- Page 185 and 186: • 170 • Simon Esmonde Cleary ra

- Page 187 and 188: • 172 • Simon Esmonde Cleary si

- Page 189 and 190: • 174 • Simon Esmonde Cleary th

- Page 191 and 192: Chapter Ten Early Historic Britain

- Page 193 and 194: • 178 • Catherine Hills retrosp

- Page 195 and 196: • 180 • Catherine Hills and the

- Page 197 and 198: • 182 • Catherine Hills Early m

- Page 199 and 200: • 184 • Catherine Hills but the

- Page 201 and 202: • 186 • Catherine Hills Attenti

- Page 203 and 204: • 188 • Catherine Hills are har

- Page 205 and 206: • 190 • Catherine Hills grave a

- Page 207 and 208: • 192 • Catherine Hills Figure

- Page 209 and 210: Chapter Eleven The Scandinavian pre

- Page 211 and 212: • 196 • Julian D.Richards There

- Page 213 and 214: • 198 • Julian D.Richards the A

- Page 215 and 216: • 200 • Julian D.Richards and a

- Page 217 and 218: • 202 • Julian D.Richards by an

- Page 219 and 220: • 204 • Julian D.Richards Figur

- Page 221 and 222: • 206 • Julian D.Richards avail

- Page 223 and 224: • 208 • Julian D.Richards stage

- Page 225 and 226: Chapter Twelve Landscapes of the Mi

- Page 227 and 228: • 212 • John Schofield Other to

- Page 229 and 230: • 214 • John Schofield A second

Roman <strong>Britain</strong>: civil and rural society<br />

• 165 •<br />

Bignor (West Sussex) or Woodchester<br />

(Gloucestershire), which stand<br />

comparison with the great<br />

continental villas, though there were<br />

also some much more modest<br />

establishments <strong>of</strong> this date, such as<br />

Barnack (Cambridgeshire).<br />

In the first spate <strong>of</strong> the provision<br />

<strong>of</strong> mosaics at the end <strong>of</strong> the second<br />

century, they were almost all laid in<br />

the new mansions in the ‘large’ towns.<br />

<strong>The</strong> main phase <strong>of</strong> mosaic laying in<br />

<strong>Britain</strong>, however, was not until the first<br />

half <strong>of</strong> the fourth century, and now<br />

the majority <strong>of</strong> these were laid at villas,<br />

with some also at residences in the<br />

‘large’ towns, reflecting the shift in<br />

display to the private sphere and the<br />

growing importance <strong>of</strong> rural seats visà-vis<br />

the main towns. Many <strong>of</strong> these<br />

mosaics showed divine figures or<br />

mythi<strong>ca</strong>l scenes, all <strong>of</strong> which were<br />

taken <strong>from</strong> Graeco-Roman, not Celtic,<br />

culture and religion (including<br />

Christianity). Until recently, it was<br />

assumed that a villa was the residence<br />

<strong>of</strong> a land-owning male aristocrat, his<br />

family and dependants. This accorded<br />

with the picture derived <strong>from</strong> the<br />

Roman agrarian writers and also<br />

unconsciously reflected the pattern <strong>of</strong><br />

the modern British land-owning<br />

aristocracy: the villa seen as protocountry-house.<br />

More recently, it has<br />

been argued that some villa plans are<br />

more amenable to dissection as a series<br />

<strong>of</strong> units <strong>of</strong> differing size and status,<br />

and thus rather than reflecting the<br />

picture outlined above, might in fact<br />

show multiple occupancy <strong>of</strong> a single<br />

villa, perhaps by different branches <strong>of</strong><br />

a descent group in a ‘Celtic’ fashion<br />

(Smith 1978). Though this suggestion<br />

is not universally accepted, it does<br />

illustrate how unstated preconceptions<br />

<strong>ca</strong>n influence interpretation, and how<br />

new approaches <strong>ca</strong>n be applied to old<br />

evidence.<br />

Figure 9.5 Gorhambury, Hertfordshire. (A) <strong>The</strong> Late Iron Age settlement;<br />

(B) the Early Roman period settlement; (C) the second-century villa; (D) the<br />

villa in the third century.<br />

Source: Neal, D.S. et al., 1990. Ex<strong>ca</strong>vation <strong>of</strong> the Iron Age, Roman and Medieval<br />

Settlement at Gorhambury, St Albans. London: English Heritage Archaeologi<strong>ca</strong>l<br />

Report 14.