The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

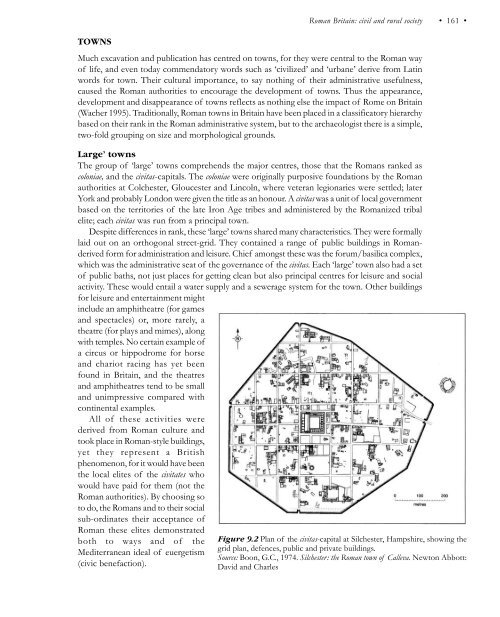

Roman Britain: civil and rural society • 161 • TOWNS Much excavation and publication has centred on towns, for they were central to the Roman way of life, and even today commendatory words such as ‘civilized’ and ‘urbane’ derive from Latin words for town. Their cultural importance, to say nothing of their administrative usefulness, caused the Roman authorities to encourage the development of towns. Thus the appearance, development and disappearance of towns reflects as nothing else the impact of Rome on Britain (Wacher 1995). Traditionally, Roman towns in Britain have been placed in a classificatory hierarchy based on their rank in the Roman administrative system, but to the archaeologist there is a simple, two-fold grouping on size and morphological grounds. Large’ towns The group of ‘large’ towns comprehends the major centres, those that the Romans ranked as coloniae, and the civitas-capitals. The coloniae were originally purposive foundations by the Roman authorities at Colchester, Gloucester and Lincoln, where veteran legionaries were settled; later York and probably London were given the title as an honour. A civitas was a unit of local government based on the territories of the late Iron Age tribes and administered by the Romanized tribal elite; each civitas was run from a principal town. Despite differences in rank, these ‘large’ towns shared many characteristics. They were formally laid out on an orthogonal street-grid. They contained a range of public buildings in Romanderived form for administration and leisure. Chief amongst these was the forum/basilica complex, which was the administrative seat of the governance of the civitas. Each ‘large’ town also had a set of public baths, not just places for getting clean but also principal centres for leisure and social activity. These would entail a water supply and a sewerage system for the town. Other buildings for leisure and entertainment might include an amphitheatre (for games and spectacles) or, more rarely, a theatre (for plays and mimes), along with temples. No certain example of a circus or hippodrome for horse and chariot racing has yet been found in Britain, and the theatres and amphitheatres tend to be small and unimpressive compared with continental examples. All of these activities were derived from Roman culture and took place in Roman-style buildings, yet they represent a British phenomenon, for it would have been the local elites of the civitates who would have paid for them (not the Roman authorities). By choosing so to do, the Romans and to their social sub-ordinates their acceptance of Roman these elites demonstrated both to ways and of the Mediterranean ideal of euergetism (civic benefaction). Figure 9.2 Plan of the civitas-capital at Silchester, Hampshire, showing the grid plan, defences, public and private buildings. Source: Boon, G.C., 1974. Silchester: the Roman town of Calleva. Newton Abbott: David and Charles

• 162 • Simon Esmonde Cleary Figure 9.3 Silchester: the forum (Hadrianic version), the baths (first period, late first century) and amphitheatre (stone phase, third-fourth century). Source: Fulford, M., 1993 in Greep, S. (ed.) Roman Towns: the Wheeler inheritance. London: Council for British Archaeology Research Report 93; St John Hope, W.H.S. and Fox, G.E., 1905. ‘Excavations on the site of the Roman city at Silchester, Hants in 1903 and 1904’, Archaeologia 59:2; Fulford, M. 1989, The Silchester Amphitheatre. London: Britannia Monograph Series 10 Initially, however, this acceptance did not extend to actually living in the towns for whose embellishment they were paying. Until the late second century, the domestic structures within these towns overwhelmingly consisted of the shops/workshops of the artisans and traders who made these towns centres of commerce. From the late second century, however, these towns were increasingly colonized by the large ‘town houses’ of the elite, so that by the fourth century they were dominated by these mansions for the private display of wealth, whilst the old public buildings fell into decay and disuse and the commercial life of the ‘large’ towns became less important to them. Most of the ‘large’ towns of Roman Britain are now covered by medieval and modern towns, but Silchester (Hampshire) was not reoccupied and is a type-site for Roman provincial towns (Figure 9.2). The 40 ha within the defences were cleared at the end of the nineteenth century, revealing the overall plan, the various public buildings (Figure 9.3) and many private buildings, principally ‘town houses’ and some commercial premises along the main thoroughfare. The cemeteries lay outside the defences, thus separating the world of the dead from that of the living; they remain unexcavated. It is now appreciated that the plan bequeathed to us by the Victorian excavations is essentially that of fourth-century Silchester. For a better impression of development through time, one must turn to Verulamium (near St Albans, Hertfordshire), another abandoned Roman town, where the excavations before the Second World War by Mortimer Wheeler and subsequently by Sheppard Frere and others have revealed a complete sequence from the Late Iron Age oppidum (Chapter 7) to the town destroyed by the Boudiccan rebellion of AD 60/61, thereafter rebuilt, enlarged, embellished and ultimately declining to extinction through the late fourth and fifth centuries.

- Page 125 and 126: • 110 • Timothy Champion range

- Page 127 and 128: • 112 • Timothy Champion Coles,

- Page 129 and 130: • 114 • Colin Haselgrove votive

- Page 131 and 132: • 116 • Colin Haselgrove Figure

- Page 133 and 134: • 118 • Colin Haselgrove Figure

- Page 135 and 136: • 120 • Colin Haselgrove ancill

- Page 137 and 138: • 122 • Colin Haselgrove East A

- Page 139 and 140: • 124 • Colin Haselgrove France

- Page 141 and 142: • 126 • Colin Haselgrove As in

- Page 143 and 144: • 128 • Colin Haselgrove distri

- Page 145 and 146: • 130 • Colin Haselgrove From 1

- Page 147 and 148: • 132 • Colin Haselgrove throug

- Page 149 and 150: • 134 • Colin Haselgrove Stead,

- Page 151 and 152: • 136 • W.S.Hanson Table 8.1 Ev

- Page 153 and 154: • 138 • W.S.Hanson country are

- Page 155 and 156: • 140 • W.S.Hanson eventually s

- Page 157 and 158: • 142 • W.S.Hanson Figure 8.4 S

- Page 159 and 160: • 144 • W.S.Hanson Figure 8.5 S

- Page 161 and 162: • 146 • W.S.Hanson Westerton, P

- Page 163 and 164: • 148 • W.S.Hanson Figure 8.8 A

- Page 165 and 166: • 150 • W.S.Hanson around 1900,

- Page 167 and 168: • 152 • W.S.Hanson provision of

- Page 169 and 170: • 154 • W.S.Hanson Figure 8.11

- Page 171 and 172: • 156 • W.S.Hanson Bibliography

- Page 173 and 174: • 158 • Simon Esmonde Cleary th

- Page 175: • 160 • Simon Esmonde Cleary pe

- Page 179 and 180: • 164 • Simon Esmonde Cleary li

- Page 181 and 182: • 166 • Simon Esmonde Cleary Ot

- Page 183 and 184: • 168 • Simon Esmonde Cleary si

- Page 185 and 186: • 170 • Simon Esmonde Cleary ra

- Page 187 and 188: • 172 • Simon Esmonde Cleary si

- Page 189 and 190: • 174 • Simon Esmonde Cleary th

- Page 191 and 192: Chapter Ten Early Historic Britain

- Page 193 and 194: • 178 • Catherine Hills retrosp

- Page 195 and 196: • 180 • Catherine Hills and the

- Page 197 and 198: • 182 • Catherine Hills Early m

- Page 199 and 200: • 184 • Catherine Hills but the

- Page 201 and 202: • 186 • Catherine Hills Attenti

- Page 203 and 204: • 188 • Catherine Hills are har

- Page 205 and 206: • 190 • Catherine Hills grave a

- Page 207 and 208: • 192 • Catherine Hills Figure

- Page 209 and 210: Chapter Eleven The Scandinavian pre

- Page 211 and 212: • 196 • Julian D.Richards There

- Page 213 and 214: • 198 • Julian D.Richards the A

- Page 215 and 216: • 200 • Julian D.Richards and a

- Page 217 and 218: • 202 • Julian D.Richards by an

- Page 219 and 220: • 204 • Julian D.Richards Figur

- Page 221 and 222: • 206 • Julian D.Richards avail

- Page 223 and 224: • 208 • Julian D.Richards stage

- Page 225 and 226: Chapter Twelve Landscapes of the Mi

Roman <strong>Britain</strong>: civil and rural society<br />

• 161 •<br />

TOWNS<br />

Much ex<strong>ca</strong>vation and publi<strong>ca</strong>tion has centred on towns, for they were central to the Roman way<br />

<strong>of</strong> life, and even today commendatory words such as ‘civilized’ and ‘urbane’ derive <strong>from</strong> Latin<br />

words for town. <strong>The</strong>ir cultural importance, to say nothing <strong>of</strong> their administrative usefulness,<br />

<strong>ca</strong>used the Roman authorities to encourage the development <strong>of</strong> towns. Thus the appearance,<br />

development and disappearance <strong>of</strong> towns reflects as nothing else the impact <strong>of</strong> Rome on <strong>Britain</strong><br />

(Wacher 1995). Traditionally, Roman towns in <strong>Britain</strong> have been placed in a classifi<strong>ca</strong>tory hierarchy<br />

based on their rank in the Roman administrative system, but to the archaeologist there is a simple,<br />

two-fold grouping on size and morphologi<strong>ca</strong>l grounds.<br />

Large’ towns<br />

<strong>The</strong> group <strong>of</strong> ‘large’ towns comprehends the major centres, those that the Romans ranked as<br />

coloniae, and the civitas-<strong>ca</strong>pitals. <strong>The</strong> coloniae were originally purposive foundations by the Roman<br />

authorities at Colchester, Gloucester and Lincoln, where veteran legionaries were settled; later<br />

York and probably London were given the title as an honour. A civitas was a unit <strong>of</strong> lo<strong>ca</strong>l government<br />

based on the territories <strong>of</strong> the late Iron Age tribes and administered by the Romanized tribal<br />

elite; each civitas was run <strong>from</strong> a principal town.<br />

Despite differences in rank, these ‘large’ towns shared many characteristics. <strong>The</strong>y were formally<br />

laid out on an orthogonal street-grid. <strong>The</strong>y contained a range <strong>of</strong> public buildings in Romanderived<br />

form for administration and leisure. Chief amongst these was the forum/basili<strong>ca</strong> complex,<br />

which was the administrative seat <strong>of</strong> the governance <strong>of</strong> the civitas. Each ‘large’ town also had a set<br />

<strong>of</strong> public baths, not just places for getting clean but also principal centres for leisure and social<br />

activity. <strong>The</strong>se would entail a water supply and a sewerage system for the town. Other buildings<br />

for leisure and entertainment might<br />

include an amphitheatre (for games<br />

and spectacles) or, more rarely, a<br />

theatre (for plays and mimes), along<br />

with temples. No certain example <strong>of</strong><br />

a circus or hippodrome for horse<br />

and chariot racing has yet been<br />

found in <strong>Britain</strong>, and the theatres<br />

and amphitheatres tend to be small<br />

and unimpressive compared with<br />

continental examples.<br />

All <strong>of</strong> these activities were<br />

derived <strong>from</strong> Roman culture and<br />

took place in Roman-style buildings,<br />

yet they represent a British<br />

phenomenon, for it would have been<br />

the lo<strong>ca</strong>l elites <strong>of</strong> the civitates who<br />

would have paid for them (not the<br />

Roman authorities). By choosing so<br />

to do, the Romans and to their social<br />

sub-ordinates their acceptance <strong>of</strong><br />

Roman these elites demonstrated<br />

both to ways and <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Mediterranean ideal <strong>of</strong> euergetism<br />

(civic benefaction).<br />

Figure 9.2 Plan <strong>of</strong> the civitas-<strong>ca</strong>pital at Silchester, Hampshire, showing the<br />

grid plan, defences, public and private buildings.<br />

Source: Boon, G.C., 1974. Silchester: the Roman town <strong>of</strong> Calleva. Newton Abbott:<br />

David and Charles