The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

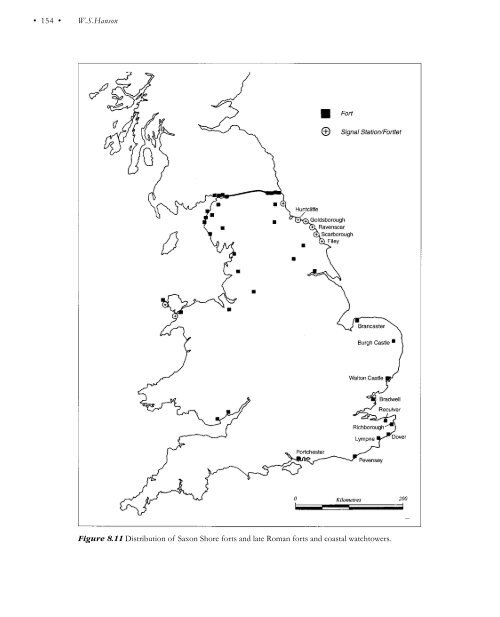

Roman Britain: military dimension • 153 • Roman frontiers were built and operated by the army, and military defence was clearly one of their prime functions, but, at least until the early fourth century AD in Britain, the process was both proactive as well as reactive. The Romans usually responded to threats to territory they occupied by undertaking a campaign against the aggressors, the principle best exemplified by the action of Agricola against the Ordovices in north Wales immediately upon his arrival in the Province as the new governor (Tacitus, Agricola, 18). Static defence from maintained positions was not normal Roman practice. When thoughts of completing the conquest of the island of Britain were given up and it was necessary to create a frontier, the Romans looked to natural features, such as the Forth-Clyde isthmus, for convenience of definition (Tacitus, Agricola, 23). Such features were at first augmented by a closer spacing of military garrisons than was the case when hostile territory was being controlled by a fort network, often utilizing smaller garrison posts, either small forts or fortlets. Other characteristic features were the provision of a system of watchtowers and of a lateral road connecting these various installations. This development can be seen on the Gask and Stanegate frontiers of late first- and early second-century date, as noted above. Only later, after Hadrian’s reign, do we see the addition of a linear barrier as part of the system. This sequence of development gives some indication of Rome’s attitude to the function of frontiers. The provision of garrisons at closer intervals and of a regular system of watchtowers suggests a concern for the control of movement across the frontier, but there is no suggestion that a system of preclusive defence was intended. Even when linear barriers were added to the system, provision was made for regular gateways at fortlets located every 1.6 km on both Hadrian’s Wall and the Antonine Wall. If the primary function of frontiers were to exclude, such an arrangement would have been both unnecessary and potentially disadvantageous, since gateways are a weak spot in any defensive circuit. On the other hand, the provision of a linear barrier would be a logical step if concern was to increase the level of control and the intensity of security. Such action would serve to funnel all legitimate movement through the gateways under the watchful eyes of the Roman garrison, making the levying of customs dues more readily achieved, and would also effectively exclude small-scale illicit movement, such as border raiding. Linear barriers are of little use against major incursions, since external forces could be massed at a selected location, easily outnumbering any local troops, and could readily breach the wall before sufficient defensive reinforcements could be summoned to the spot. Whether or not the wall line was ever intended to be defended as a barrier in the way that the perimeter of a fort would have been is much disputed. Clearly, the original thickness of Hadrian’s Wall (the so-called ‘broad wall’) could have accommodated a walkway, though there is no direct evidence that it was provided with the necessary parapet or crenellations. The reduction in the width of later sections of this wall to as little as 1.3 m, however, decreases the probability that it could have been used as a fighting platform. Evidence from the Antonine Wall is more difficult to assess since the details of the superstructure of the turf rampart are less certain. Analogy with the German frontier, however, where the barrier consisted of only a timber palisade, makes clear that the use of such barriers as elevated fighting platforms requires proof rather than being automatically assumed. It has been further suggested that the provision of a linear barrier would provide greater protection to the local population within the Province, thus encouraging and facilitating the process of Romanization (Hanson and Maxwell 1986, 163). However, whether this was the intended function rather than an incidental side-effect remains unproven. Debate about the function of the Saxon Shore is more fundamental, since its very identification as a frontier has been challenged. Recent reassessment of the evidence suggests that the forts there do not readily fit into any practical defensive strategy, but should better be seen as trans-shipment centres for the collection and distribution of state supplies (Cotterill 1993). However, various

• 154 • W.S.Hanson Figure 8.11 Distribution of Saxon Shore forts and late Roman forts and coastal watchtowers.

- Page 117 and 118: • 102 • Timothy Champion Little

- Page 119 and 120: • 104 • Timothy Champion CRAFT,

- Page 121 and 122: • 106 • Timothy Champion solely

- Page 123 and 124: • 108 • Timothy Champion and re

- Page 125 and 126: • 110 • Timothy Champion range

- Page 127 and 128: • 112 • Timothy Champion Coles,

- Page 129 and 130: • 114 • Colin Haselgrove votive

- Page 131 and 132: • 116 • Colin Haselgrove Figure

- Page 133 and 134: • 118 • Colin Haselgrove Figure

- Page 135 and 136: • 120 • Colin Haselgrove ancill

- Page 137 and 138: • 122 • Colin Haselgrove East A

- Page 139 and 140: • 124 • Colin Haselgrove France

- Page 141 and 142: • 126 • Colin Haselgrove As in

- Page 143 and 144: • 128 • Colin Haselgrove distri

- Page 145 and 146: • 130 • Colin Haselgrove From 1

- Page 147 and 148: • 132 • Colin Haselgrove throug

- Page 149 and 150: • 134 • Colin Haselgrove Stead,

- Page 151 and 152: • 136 • W.S.Hanson Table 8.1 Ev

- Page 153 and 154: • 138 • W.S.Hanson country are

- Page 155 and 156: • 140 • W.S.Hanson eventually s

- Page 157 and 158: • 142 • W.S.Hanson Figure 8.4 S

- Page 159 and 160: • 144 • W.S.Hanson Figure 8.5 S

- Page 161 and 162: • 146 • W.S.Hanson Westerton, P

- Page 163 and 164: • 148 • W.S.Hanson Figure 8.8 A

- Page 165 and 166: • 150 • W.S.Hanson around 1900,

- Page 167: • 152 • W.S.Hanson provision of

- Page 171 and 172: • 156 • W.S.Hanson Bibliography

- Page 173 and 174: • 158 • Simon Esmonde Cleary th

- Page 175 and 176: • 160 • Simon Esmonde Cleary pe

- Page 177 and 178: • 162 • Simon Esmonde Cleary Fi

- Page 179 and 180: • 164 • Simon Esmonde Cleary li

- Page 181 and 182: • 166 • Simon Esmonde Cleary Ot

- Page 183 and 184: • 168 • Simon Esmonde Cleary si

- Page 185 and 186: • 170 • Simon Esmonde Cleary ra

- Page 187 and 188: • 172 • Simon Esmonde Cleary si

- Page 189 and 190: • 174 • Simon Esmonde Cleary th

- Page 191 and 192: Chapter Ten Early Historic Britain

- Page 193 and 194: • 178 • Catherine Hills retrosp

- Page 195 and 196: • 180 • Catherine Hills and the

- Page 197 and 198: • 182 • Catherine Hills Early m

- Page 199 and 200: • 184 • Catherine Hills but the

- Page 201 and 202: • 186 • Catherine Hills Attenti

- Page 203 and 204: • 188 • Catherine Hills are har

- Page 205 and 206: • 190 • Catherine Hills grave a

- Page 207 and 208: • 192 • Catherine Hills Figure

- Page 209 and 210: Chapter Eleven The Scandinavian pre

- Page 211 and 212: • 196 • Julian D.Richards There

- Page 213 and 214: • 198 • Julian D.Richards the A

- Page 215 and 216: • 200 • Julian D.Richards and a

- Page 217 and 218: • 202 • Julian D.Richards by an

• 154 • W.S.Hanson<br />

Figure 8.11 Distribution <strong>of</strong> Saxon Shore forts and late Roman forts and coastal watchtowers.