The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

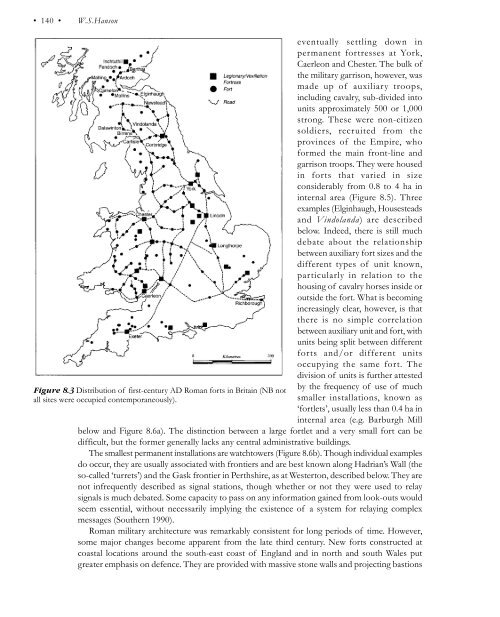

Roman Britain: military dimension • 139 • underlying order of military life, while tombstones can indicate the origin of those troops, their life expectancy and family relationships (e.g. Figure 8.1). All three types of inscription can assist in the study of the movement of particular units or the careers of individuals, which, in turn, can contribute both to refining the chronology and interpreting the significance of historical events. The major contribution of archaeology is in the elucidation of military installations in terms of date and function. When on campaign in hostile territory, or simply operating away from home base, the Roman army constructed temporary defended enclosures, referred to as ‘temporary camps’, for overnight protection. More are known from Britain than from any other province of the Roman Empire. They range in size dramatically, from 0.4 ha to 67 ha in area. The smaller examples are more likely to relate to the building activities of work parties involved in the construction or repair of military installations, but the larger camps can indicate the lines of march of troops on campaign, and are sometimes termed ‘marching camps’ (e.g. Ardoch below) (Figure 8.2). Semi-permanent works, often referred to as ‘vexillation fortresses’ and covering an area of some 8 ha, are occasionally attested. They are usually associated with campaigning and were perhaps linked to the provision of adequate supplies, though the precise nature of such sites is much debated (e.g. Red House, Corbridge, below and Figure 8.4). After its conquest had been achieved, control of an area was usually consolidated by a more permanent military presence, though the nature and extent of this varies according to the political geography of the area concerned. Close military control was usually manifested in the form of a network efforts and fortlets linked by a road system. This pattern is seen in Wales, northern England and Scotland in the first and second centuries AD, although such close supervision of conquered territory is not recorded in south-eastern England (Figure 8.3). Here more sophisticated means of political control seem to have been applied immediately after the conquest, involving the use of diplomacy and the establishment of client or ‘friendly’ kings in an area where native political organization may have been more complex (Chapter 7) and where the opposition was, perhaps, less intransigent. When establishing military control of an area, the Romans utilized a hierarchy of permanent military establishments. At its hub were the legionary fortresses, bases for some 5,000 citizen infantry who formed the core of the Roman army (e.g. Inchtuthil below and Figure 8.4). Only four legions were used in the invasion of Britain and, by the mid- 80s AD, only three remained in garrison. Legionary movements fluctuated considerably in the early years of campaigning and conquest, Figure 8.2 Aerial photograph of the fort (F), annexe (A) and temporary camps (C) at Malling, Perthshire. Source: Crown copyright: Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland.

• 140 • W.S.Hanson eventually settling down in permanent fortresses at York, Caerleon and Chester. The bulk of the military garrison, however, was made up of auxiliary troops, including cavalry, sub-divided into units approximately 500 or 1,000 strong. These were non-citizen soldiers, recruited from the provinces of the Empire, who formed the main front-line and garrison troops. They were housed in forts that varied in size considerably from 0.8 to 4 ha in internal area (Figure 8.5). Three examples (Elginhaugh, Housesteads and Vindolanda) are described below. Indeed, there is still much debate about the relationship between auxiliary fort sizes and the different types of unit known, particularly in relation to the housing of cavalry horses inside or outside the fort. What is becoming increasingly clear, however, is that there is no simple correlation between auxiliary unit and fort, with units being split between different forts and/or different units occupying the same fort. The division of units is further attested Figure 8.3 Distribution of first-century AD Roman forts in Britain (NB not by the frequency of use of much all sites were occupied contemporaneously). smaller installations, known as ‘fortlets’, usually less than 0.4 ha in internal area (e.g. Barburgh Mill below and Figure 8.6a). The distinction between a large fortlet and a very small fort can be difficult, but the former generally lacks any central administrative buildings. The smallest permanent installations are watchtowers (Figure 8.6b). Though individual examples do occur, they are usually associated with frontiers and are best known along Hadrian’s Wall (the so-called ‘turrets’) and the Gask frontier in Perthshire, as at Westerton, described below. They are not infrequently described as signal stations, though whether or not they were used to relay signals is much debated. Some capacity to pass on any information gained from look-outs would seem essential, without necessarily implying the existence of a system for relaying complex messages (Southern 1990). Roman military architecture was remarkably consistent for long periods of time. However, some major changes become apparent from the late third century. New forts constructed at coastal locations around the south-east coast of England and in north and south Wales put greater emphasis on defence. They are provided with massive stone walls and projecting bastions

- Page 103 and 104: • 88 • Mike Parker Pearson Figu

- Page 105 and 106: • 90 • Mike Parker Pearson are

- Page 107 and 108: • 92 • Mike Parker Pearson Bron

- Page 109 and 110: • 94 • Mike Parker Pearson Elli

- Page 111 and 112: • 96 • Timothy Champion For the

- Page 113 and 114: • 98 • Timothy Champion Perhaps

- Page 115 and 116: • 100 • Timothy Champion Figure

- Page 117 and 118: • 102 • Timothy Champion Little

- Page 119 and 120: • 104 • Timothy Champion CRAFT,

- Page 121 and 122: • 106 • Timothy Champion solely

- Page 123 and 124: • 108 • Timothy Champion and re

- Page 125 and 126: • 110 • Timothy Champion range

- Page 127 and 128: • 112 • Timothy Champion Coles,

- Page 129 and 130: • 114 • Colin Haselgrove votive

- Page 131 and 132: • 116 • Colin Haselgrove Figure

- Page 133 and 134: • 118 • Colin Haselgrove Figure

- Page 135 and 136: • 120 • Colin Haselgrove ancill

- Page 137 and 138: • 122 • Colin Haselgrove East A

- Page 139 and 140: • 124 • Colin Haselgrove France

- Page 141 and 142: • 126 • Colin Haselgrove As in

- Page 143 and 144: • 128 • Colin Haselgrove distri

- Page 145 and 146: • 130 • Colin Haselgrove From 1

- Page 147 and 148: • 132 • Colin Haselgrove throug

- Page 149 and 150: • 134 • Colin Haselgrove Stead,

- Page 151 and 152: • 136 • W.S.Hanson Table 8.1 Ev

- Page 153: • 138 • W.S.Hanson country are

- Page 157 and 158: • 142 • W.S.Hanson Figure 8.4 S

- Page 159 and 160: • 144 • W.S.Hanson Figure 8.5 S

- Page 161 and 162: • 146 • W.S.Hanson Westerton, P

- Page 163 and 164: • 148 • W.S.Hanson Figure 8.8 A

- Page 165 and 166: • 150 • W.S.Hanson around 1900,

- Page 167 and 168: • 152 • W.S.Hanson provision of

- Page 169 and 170: • 154 • W.S.Hanson Figure 8.11

- Page 171 and 172: • 156 • W.S.Hanson Bibliography

- Page 173 and 174: • 158 • Simon Esmonde Cleary th

- Page 175 and 176: • 160 • Simon Esmonde Cleary pe

- Page 177 and 178: • 162 • Simon Esmonde Cleary Fi

- Page 179 and 180: • 164 • Simon Esmonde Cleary li

- Page 181 and 182: • 166 • Simon Esmonde Cleary Ot

- Page 183 and 184: • 168 • Simon Esmonde Cleary si

- Page 185 and 186: • 170 • Simon Esmonde Cleary ra

- Page 187 and 188: • 172 • Simon Esmonde Cleary si

- Page 189 and 190: • 174 • Simon Esmonde Cleary th

- Page 191 and 192: Chapter Ten Early Historic Britain

- Page 193 and 194: • 178 • Catherine Hills retrosp

- Page 195 and 196: • 180 • Catherine Hills and the

- Page 197 and 198: • 182 • Catherine Hills Early m

- Page 199 and 200: • 184 • Catherine Hills but the

- Page 201 and 202: • 186 • Catherine Hills Attenti

- Page 203 and 204: • 188 • Catherine Hills are har

• 140 • W.S.Hanson<br />

eventually settling down in<br />

permanent fortresses at York,<br />

Caerleon and Chester. <strong>The</strong> bulk <strong>of</strong><br />

the military garrison, however, was<br />

made up <strong>of</strong> auxiliary troops,<br />

including <strong>ca</strong>valry, sub-divided into<br />

units approximately 500 or 1,000<br />

strong. <strong>The</strong>se were non-citizen<br />

soldiers, recruited <strong>from</strong> the<br />

provinces <strong>of</strong> the Empire, who<br />

formed the main front-line and<br />

garrison troops. <strong>The</strong>y were housed<br />

in forts that varied in size<br />

considerably <strong>from</strong> 0.8 to 4 ha in<br />

internal area (Figure 8.5). Three<br />

examples (Elginhaugh, Housesteads<br />

and Vindolanda) are described<br />

below. Indeed, there is still much<br />

debate about the relationship<br />

between auxiliary fort sizes and the<br />

different types <strong>of</strong> unit known,<br />

particularly in relation to the<br />

housing <strong>of</strong> <strong>ca</strong>valry horses inside or<br />

outside the fort. What is becoming<br />

increasingly clear, however, is that<br />

there is no simple correlation<br />

between auxiliary unit and fort, with<br />

units being split between different<br />

forts and/or different units<br />

occupying the same fort. <strong>The</strong><br />

division <strong>of</strong> units is further attested<br />

Figure 8.3 Distribution <strong>of</strong> first-century AD Roman forts in <strong>Britain</strong> (NB not<br />

by the frequency <strong>of</strong> use <strong>of</strong> much<br />

all sites were occupied contemporaneously).<br />

smaller installations, known as<br />

‘fortlets’, usually less than 0.4 ha in<br />

internal area (e.g. Barburgh Mill<br />

below and Figure 8.6a). <strong>The</strong> distinction between a large fortlet and a very small fort <strong>ca</strong>n be<br />

difficult, but the former generally lacks any central administrative buildings.<br />

<strong>The</strong> smallest permanent installations are watchtowers (Figure 8.6b). Though individual examples<br />

do occur, they are usually associated with frontiers and are best known along Hadrian’s Wall (the<br />

so-<strong>ca</strong>lled ‘turrets’) and the Gask frontier in Perthshire, as at Westerton, described below. <strong>The</strong>y are<br />

not infrequently described as signal stations, though whether or not they were used to relay<br />

signals is much debated. Some <strong>ca</strong>pacity to pass on any information gained <strong>from</strong> look-outs would<br />

seem essential, without necessarily implying the existence <strong>of</strong> a system for relaying complex<br />

messages (Southern 1990).<br />

Roman military architecture was remarkably consistent for long periods <strong>of</strong> time. However,<br />

some major changes become apparent <strong>from</strong> the late third century. New forts constructed at<br />

coastal lo<strong>ca</strong>tions around the south-east coast <strong>of</strong> England and in north and south Wales put<br />

greater emphasis on defence. <strong>The</strong>y are provided with massive stone walls and projecting bastions