The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

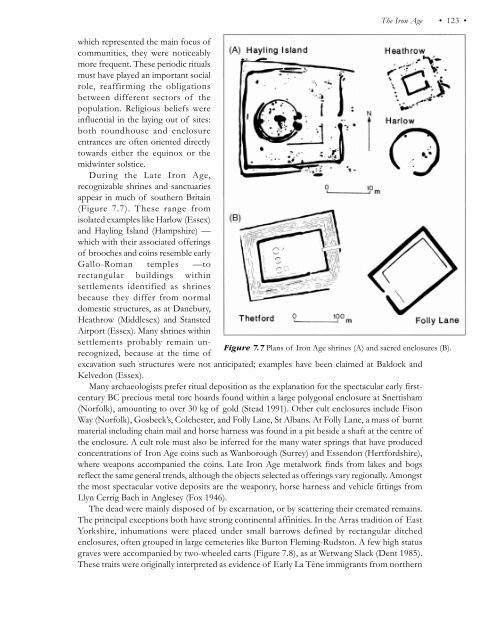

The Iron Age • 123 • which represented the main focus of communities, they were noticeably more frequent. These periodic rituals must have played an important social role, reaffirming the obligations between different sectors of the population. Religious beliefs were influential in the laying out of sites: both roundhouse and enclosure entrances are often oriented directly towards either the equinox or the midwinter solstice. During the Late Iron Age, recognizable shrines and sanctuaries appear in much of southern Britain (Figure 7.7). These range from isolated examples like Harlow (Essex) and Hayling Island (Hampshire) — which with their associated offerings of brooches and coins resemble early Gallo-Roman temples —to rectangular buildings within settlements identified as shrines because they differ from normal domestic structures, as at Danebury, Heathrow (Middlesex) and Stansted Airport (Essex). Many shrines within settlements probably remain unrecognized, because at the time of Figure 7.7 Plans of Iron Age shrines (A) and sacred enclosures (B). excavation such structures were not anticipated; examples have been claimed at Baldock and Kelvedon (Essex). Many archaeologists prefer ritual deposition as the explanation for the spectacular early firstcentury BC precious metal torc hoards found within a large polygonal enclosure at Snettisham (Norfolk), amounting to over 30 kg of gold (Stead 1991). Other cult enclosures include Fison Way (Norfolk), Gosbeck’s, Colchester, and Folly Lane, St Albans. At Folly Lane, a mass of burnt material including chain mail and horse harness was found in a pit beside a shaft at the centre of the enclosure. A cult role must also be inferred for the many water springs that have produced concentrations of Iron Age coins such as Wanborough (Surrey) and Essendon (Hertfordshire), where weapons accompanied the coins. Late Iron Age metalwork finds from lakes and bogs reflect the same general trends, although the objects selected as offerings vary regionally. Amongst the most spectacular votive deposits are the weaponry, horse harness and vehicle fittings from Llyn Cerrig Bach in Anglesey (Fox 1946). The dead were mainly disposed of by excarnation, or by scattering their cremated remains. The principal exceptions both have strong continental affinities. In the Arras tradition of East Yorkshire, inhumations were placed under small barrows defined by rectangular ditched enclosures, often grouped in large cemeteries like Burton Fleming-Rudston. A few high status graves were accompanied by two-wheeled carts (Figure 7.8), as at Wetwang Slack (Dent 1985). These traits were originally interpreted as evidence of Early La Tène immigrants from northern

• 124 • Colin Haselgrove France, but differences from continental practice are apparent and a plausible alternative is to envisage a ruling group with far-flung contacts adopting exotic burial rites. Although the earliest Arras burials could belong to the late fifth century BC, the tradition peaked in the third and second centuries BC. The Aylesford cremation rite, introduced into south-east England in the late second century BC, displays close affinities with burial practice in northern France. Burial grounds are typically small, but larger cemeteries are known at King Harry Lane, St Albans, and Westhampnett, near Chichester (Fitzpatrick 1997). Most cremations were accompanied by at most two pottery vessels and occasionally items such as brooches or sets of toilet instruments. In some cases, the cremations lay within enclosures or clusters that suggest kin-groups. A few richer burials occur, mostly north of the Thames, as at Baldock and Welwyn Garden City (Hertfordshire). Their contents emphasize drinking and feasting: Italian wine amphorae and serving vessels are accompanied by indigenous, high status items such as buckets, hearth furniture and gaming Figure 7.8 Grave plans: A. cart burial from Wetwang Slack; B. cremation sets. Warrior equipment is virtually burial from Westhampnett. absent from Aylesford burials, Sources: A—Dent 1985; B—Fitzpatrick 1997 although it does occur in some of the East Yorkshire graves and in a few individual burials elsewhere. At Mill Hill, Deal (Kent), for example, the grave of a young man dating to the late third century BC contained a sword, shield and bronze head-dress (Parfitt 1995). Other less prominent Iron Age burial traditions occur in several regions. Cist graves were used in Cornwall between the fifth century BC and the first century AD, while a tradition of crouched inhumation burial developed in Dorset during the first century BC. With the aid of radiocarbon dating, a number of unfurnished inhumation cemeteries are now attributable to the Later Iron Age from places as far apart as Kent and the Lothian plain. Also plausibly of Iron Age date are Lindow Man (Cheshire) and some of the other bog body finds from north-west England, many of whom appear to have been ritually executed (Stead et al. 1986).

- Page 87 and 88: • 72 • Alasdair Whittle hundred

- Page 89 and 90: • 74 • Alasdair Whittle and els

- Page 91 and 92: • 76 • Alasdair Whittle Moffett

- Page 93 and 94: • 78 • Mike Parker Pearson diff

- Page 95 and 96: • 80 • Mike Parker Pearson Figu

- Page 97 and 98: • 82 • Mike Parker Pearson argu

- Page 99 and 100: • 84 • Mike Parker Pearson Late

- Page 101 and 102: • 86 • Mike Parker Pearson been

- Page 103 and 104: • 88 • Mike Parker Pearson Figu

- Page 105 and 106: • 90 • Mike Parker Pearson are

- Page 107 and 108: • 92 • Mike Parker Pearson Bron

- Page 109 and 110: • 94 • Mike Parker Pearson Elli

- Page 111 and 112: • 96 • Timothy Champion For the

- Page 113 and 114: • 98 • Timothy Champion Perhaps

- Page 115 and 116: • 100 • Timothy Champion Figure

- Page 117 and 118: • 102 • Timothy Champion Little

- Page 119 and 120: • 104 • Timothy Champion CRAFT,

- Page 121 and 122: • 106 • Timothy Champion solely

- Page 123 and 124: • 108 • Timothy Champion and re

- Page 125 and 126: • 110 • Timothy Champion range

- Page 127 and 128: • 112 • Timothy Champion Coles,

- Page 129 and 130: • 114 • Colin Haselgrove votive

- Page 131 and 132: • 116 • Colin Haselgrove Figure

- Page 133 and 134: • 118 • Colin Haselgrove Figure

- Page 135 and 136: • 120 • Colin Haselgrove ancill

- Page 137: • 122 • Colin Haselgrove East A

- Page 141 and 142: • 126 • Colin Haselgrove As in

- Page 143 and 144: • 128 • Colin Haselgrove distri

- Page 145 and 146: • 130 • Colin Haselgrove From 1

- Page 147 and 148: • 132 • Colin Haselgrove throug

- Page 149 and 150: • 134 • Colin Haselgrove Stead,

- Page 151 and 152: • 136 • W.S.Hanson Table 8.1 Ev

- Page 153 and 154: • 138 • W.S.Hanson country are

- Page 155 and 156: • 140 • W.S.Hanson eventually s

- Page 157 and 158: • 142 • W.S.Hanson Figure 8.4 S

- Page 159 and 160: • 144 • W.S.Hanson Figure 8.5 S

- Page 161 and 162: • 146 • W.S.Hanson Westerton, P

- Page 163 and 164: • 148 • W.S.Hanson Figure 8.8 A

- Page 165 and 166: • 150 • W.S.Hanson around 1900,

- Page 167 and 168: • 152 • W.S.Hanson provision of

- Page 169 and 170: • 154 • W.S.Hanson Figure 8.11

- Page 171 and 172: • 156 • W.S.Hanson Bibliography

- Page 173 and 174: • 158 • Simon Esmonde Cleary th

- Page 175 and 176: • 160 • Simon Esmonde Cleary pe

- Page 177 and 178: • 162 • Simon Esmonde Cleary Fi

- Page 179 and 180: • 164 • Simon Esmonde Cleary li

- Page 181 and 182: • 166 • Simon Esmonde Cleary Ot

- Page 183 and 184: • 168 • Simon Esmonde Cleary si

- Page 185 and 186: • 170 • Simon Esmonde Cleary ra

- Page 187 and 188: • 172 • Simon Esmonde Cleary si

<strong>The</strong> Iron Age<br />

• 123 •<br />

which represented the main focus <strong>of</strong><br />

communities, they were noticeably<br />

more frequent. <strong>The</strong>se periodic rituals<br />

must have played an important social<br />

role, reaffirming the obligations<br />

between different sectors <strong>of</strong> the<br />

population. Religious beliefs were<br />

influential in the laying out <strong>of</strong> sites:<br />

both roundhouse and enclosure<br />

entrances are <strong>of</strong>ten oriented directly<br />

towards either the equinox or the<br />

midwinter solstice.<br />

During the Late Iron Age,<br />

recognizable shrines and sanctuaries<br />

appear in much <strong>of</strong> southern <strong>Britain</strong><br />

(Figure 7.7). <strong>The</strong>se range <strong>from</strong><br />

isolated examples like Harlow (Essex)<br />

and Hayling Island (Hampshire) —<br />

which with their associated <strong>of</strong>ferings<br />

<strong>of</strong> brooches and coins resemble early<br />

Gallo-Roman temples —to<br />

rectangular buildings within<br />

settlements identified as shrines<br />

be<strong>ca</strong>use they differ <strong>from</strong> normal<br />

domestic structures, as at Danebury,<br />

Heathrow (Middlesex) and Stansted<br />

Airport (Essex). Many shrines within<br />

settlements probably remain unrecognized,<br />

be<strong>ca</strong>use at the time <strong>of</strong><br />

Figure 7.7 Plans <strong>of</strong> Iron Age shrines (A) and sacred enclosures (B).<br />

ex<strong>ca</strong>vation such structures were not anticipated; examples have been claimed at Baldock and<br />

Kelvedon (Essex).<br />

Many archaeologists prefer ritual deposition as the explanation for the spectacular early firstcentury<br />

BC precious metal torc hoards found within a large polygonal enclosure at Snettisham<br />

(Norfolk), amounting to over 30 kg <strong>of</strong> gold (Stead 1991). Other cult enclosures include Fison<br />

Way (Norfolk), Gosbeck’s, Colchester, and Folly Lane, St Albans. At Folly Lane, a mass <strong>of</strong> burnt<br />

material including chain mail and horse harness was found in a pit beside a shaft at the centre <strong>of</strong><br />

the enclosure. A cult role must also be inferred for the many water springs that have produced<br />

concentrations <strong>of</strong> Iron Age coins such as Wanborough (Surrey) and Essendon (Hertfordshire),<br />

where weapons accompanied the coins. Late Iron Age metalwork finds <strong>from</strong> lakes and bogs<br />

reflect the same general trends, although the objects selected as <strong>of</strong>ferings vary regionally. Amongst<br />

the most spectacular votive deposits are the weaponry, horse harness and vehicle fittings <strong>from</strong><br />

Llyn Cerrig Bach in <strong>An</strong>glesey (Fox 1946).<br />

<strong>The</strong> dead were mainly disposed <strong>of</strong> by ex<strong>ca</strong>rnation, or by s<strong>ca</strong>ttering their cremated remains.<br />

<strong>The</strong> principal exceptions both have strong continental affinities. In the Arras tradition <strong>of</strong> East<br />

Yorkshire, inhumations were placed under small barrows defined by rectangular ditched<br />

enclosures, <strong>of</strong>ten grouped in large cemeteries like Burton Fleming-Rudston. A few high status<br />

graves were accompanied by two-wheeled <strong>ca</strong>rts (Figure 7.8), as at Wetwang Slack (Dent 1985).<br />

<strong>The</strong>se traits were originally interpreted as evidence <strong>of</strong> Early La Tène immigrants <strong>from</strong> northern