The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

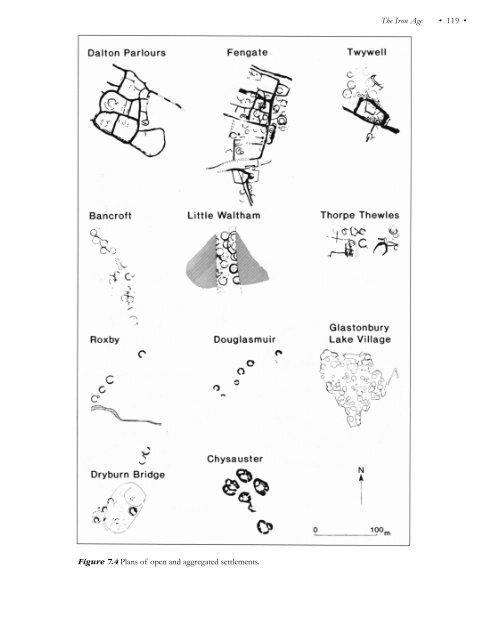

The Iron Age • 119 • Figure 7.4 Plans of open and aggregated settlements.

• 120 • Colin Haselgrove ancillary structures and byres, not houses, and the excavator’s estimate of the Later Iron Age population is five households (Pryor 1984). A rather larger population has been suggested for the Glastonbury lake village (Somerset), reaching a maximum of 14 households in the early first century BC, before increasingly wet conditions led to contraction and abandonment (Coles and Minnitt 1995). A number of Roman small towns seem to originate in Late Iron Age aggregated settlements, as at Baldock (Hertfordshire). In the upper Thames Valley of Oxfordshire, different settlement types are seen on the upper and lower gravel terraces (Lambrick 1992). The second terrace is dominated by aggregated settlements like Abingdon Ashville and Gravelly Guy, with separate areas for pit storage and domestic occupation. These sites may have operated communally, each with its strip of arable at the terrace edge, but sharing pasture away from the river. A different settlement type is found on the first terrace, reflecting an expansion of pastoral farming during the Later Iron Age. These are smaller, self-contained ditched or hedged enclosures with funnel entrances, as at Hardwick. Lastly, a scatter of short-lived seasonally occupied sites were established on the floodplain to exploit summer grazing. Seasonal settlements are known elsewhere, some linked to part-time craft specialization, as at Eldon’s Seat (Dorset), where Kimmeridge Shale bracelets were manufactured. The wetland settlement at Meare (Somerset) is now interpreted as the site of a seasonal fair. The main period of hillfort building in southern England occurred during the sixth and fifth centuries BC. However, the defence of hill-tops in Britain has a long and varied history, with construction peaking at different times in different regions. In north and central Wales, for example, the earliest hillforts like the Breiddin (Powys) succeeded Bronze Age enclosures, whereas in East Anglia and the Weald, most hillforts were built in the Later Iron Age. Scottish sites like Eildon Hill North (Roxburghshire) and Traprain Law (East Lothian) were apparently abandoned as centres of habitation before the classic southern British hillforts were even built, although they were reoccupied during the Roman Iron Age and may have retained a ceremonial role during the intervening centuries. In southern England, the earliest hillforts occur from the Cotswolds along the chalk downs of north Wessex as far as the Chiltern scarp. These early hillforts comprise two main categories: smaller, well-fortified sites with dense internal activity, as at Crickley Hill (Gloucestershire) or Moel-y-Gaer (Powys), and larger hilltop enclosures like Bathampton Down (Avon), with scant evidence of any occupation. At this stage, the defences usually consisted of a single earth or stone rampart, often of box-framed or timberlaced construction, with a relatively simple entrance. After c.350 BC, many early hillforts in Wessex and elsewhere were abandoned, while a smaller number, generally known as developed hillforts, were extended and often massively elaborated. These were usually protected by multiple glacisstyle earthworks, constructed so that the external face of each dump rampart formed a continuous profile with a V-shaped ditch, while entrances often consisted of long passages protected by complex outworks. Good examples of developed hillforts include Cadbury Castle (Somerset), Croft Ambrey (Herefordshire), Danebury (Hampshire) and Maiden Castle (Dorset). Although neither Danebury—where more than half the interior has been excavated—nor Maiden Castle can be considered typical of British sites, between them they exemplify the main features of both early and developed hillforts, as well as illustrating the processes by which certain hillforts rose to dominate their locality between the fourth and second centuries BC. Their earlier occupation phases were characterized by well-ordered layouts, and by possession of substantial food storage capacities. At Danebury (Cunliffe 1993), the northern interior was occupied by rows of four-post storage structures—later replaced by a mass of storage pits—while a limited number of circular buildings were constructed in its southern half and around the circumference (Figure 7.5). At this stage, finds apart from pottery were relatively sparse at either hillfort.

- Page 83 and 84: • 68 • Alasdair Whittle Figure

- Page 85 and 86: • 70 • Alasdair Whittle inter-

- Page 87 and 88: • 72 • Alasdair Whittle hundred

- Page 89 and 90: • 74 • Alasdair Whittle and els

- Page 91 and 92: • 76 • Alasdair Whittle Moffett

- Page 93 and 94: • 78 • Mike Parker Pearson diff

- Page 95 and 96: • 80 • Mike Parker Pearson Figu

- Page 97 and 98: • 82 • Mike Parker Pearson argu

- Page 99 and 100: • 84 • Mike Parker Pearson Late

- Page 101 and 102: • 86 • Mike Parker Pearson been

- Page 103 and 104: • 88 • Mike Parker Pearson Figu

- Page 105 and 106: • 90 • Mike Parker Pearson are

- Page 107 and 108: • 92 • Mike Parker Pearson Bron

- Page 109 and 110: • 94 • Mike Parker Pearson Elli

- Page 111 and 112: • 96 • Timothy Champion For the

- Page 113 and 114: • 98 • Timothy Champion Perhaps

- Page 115 and 116: • 100 • Timothy Champion Figure

- Page 117 and 118: • 102 • Timothy Champion Little

- Page 119 and 120: • 104 • Timothy Champion CRAFT,

- Page 121 and 122: • 106 • Timothy Champion solely

- Page 123 and 124: • 108 • Timothy Champion and re

- Page 125 and 126: • 110 • Timothy Champion range

- Page 127 and 128: • 112 • Timothy Champion Coles,

- Page 129 and 130: • 114 • Colin Haselgrove votive

- Page 131 and 132: • 116 • Colin Haselgrove Figure

- Page 133: • 118 • Colin Haselgrove Figure

- Page 137 and 138: • 122 • Colin Haselgrove East A

- Page 139 and 140: • 124 • Colin Haselgrove France

- Page 141 and 142: • 126 • Colin Haselgrove As in

- Page 143 and 144: • 128 • Colin Haselgrove distri

- Page 145 and 146: • 130 • Colin Haselgrove From 1

- Page 147 and 148: • 132 • Colin Haselgrove throug

- Page 149 and 150: • 134 • Colin Haselgrove Stead,

- Page 151 and 152: • 136 • W.S.Hanson Table 8.1 Ev

- Page 153 and 154: • 138 • W.S.Hanson country are

- Page 155 and 156: • 140 • W.S.Hanson eventually s

- Page 157 and 158: • 142 • W.S.Hanson Figure 8.4 S

- Page 159 and 160: • 144 • W.S.Hanson Figure 8.5 S

- Page 161 and 162: • 146 • W.S.Hanson Westerton, P

- Page 163 and 164: • 148 • W.S.Hanson Figure 8.8 A

- Page 165 and 166: • 150 • W.S.Hanson around 1900,

- Page 167 and 168: • 152 • W.S.Hanson provision of

- Page 169 and 170: • 154 • W.S.Hanson Figure 8.11

- Page 171 and 172: • 156 • W.S.Hanson Bibliography

- Page 173 and 174: • 158 • Simon Esmonde Cleary th

- Page 175 and 176: • 160 • Simon Esmonde Cleary pe

- Page 177 and 178: • 162 • Simon Esmonde Cleary Fi

- Page 179 and 180: • 164 • Simon Esmonde Cleary li

- Page 181 and 182: • 166 • Simon Esmonde Cleary Ot

- Page 183 and 184: • 168 • Simon Esmonde Cleary si

<strong>The</strong> Iron Age<br />

• 119 •<br />

Figure 7.4 Plans <strong>of</strong> open and aggregated settlements.