The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca The Archaeology of Britain: An introduction from ... - waughfamily.ca

The Later Bronze Age • 99 • much attention, but elsewhere, as in Wales, almost nothing is known of contemporary settlement. The key sites are best reviewed on a regional basis. In eastern England, the earlier part of the period is characterized by small cremation cemeteries with local variants of the Deverel-Rimbury pottery tradition, and some evidence for settlements. At Fengate, Peterborough (Pryor 1991: 52–73), these were associated with extensive field systems laid out around the thirteenth century BC, designed for efficient management of a pastoral cattle economy. The most striking site of the whole British Later Bronze Age has been excavated at Flag Fen, near Peterborough (Pryor 1991; 1992). As the fens grew wetter and formed a shallow inlet of the sea, a massive timber platform was constructed about 1000 BC in the open water at the mouth of the bay. It was linked Figure 6.3 Deverel-Rimbury pottery. Sources: (left and upper right) Annable, F.K. and Simpson, D.D.A., 1964. Guide catalogue of the Neolithic and Bronze Age collections in Devizes Museum. Devizes: Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Figs 576 and 566 respectively, (lower right) Dacre, M. and Ellison, A., 1981. ‘A Bronze Age urn cemetery at Kimpton, Hampshire’, Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 47, 147–203, Fig. 19. to the dry land on either side by an alignment of vertical posts more than a kilometre long. In the peat alongside this alignment were found nearly 300 metal items, together with animal bones and pottery, all originally dropped or carefully placed into the water of the bay. The metal items are mainly of bronze, but a few are pure tin; most belong to the Later Bronze Age, but some are of Iron Age date. They include many rings, pins and other small items, as well as swords, spears and daggers, and fragments of bronze helmets. This extraordinary site shows a long-lasting tradition of depositing objects in watery places. Similar practices are well known from major rivers, especially the Thames, which has a long history of dredging and archaeological observation. The material recovered from the river bed spans a very long period, but there are particular concentrations of Later Bronze Age metalwork in certain stretches. These are not randomly chosen items, but include especially swords and certain types of spearhead. Human skeletal remains have also been found in the river, and again there is a concentration of dated examples in the Later Bronze Age, suggesting a link between the deposition of metalwork in the river and the disposal of at least some of the dead (Bradley and Gordon 1988). Settlement evidence in the middle and lower Thames Valley suggests a considerable density of population. In the tributary valley of the Kennet, there is a particularly high concentration of sites, such as Aldermaston Wharf, Berkshire (Bradley et al. 1980); these are unenclosed clusters of round houses and pits, showing evidence for a mixed agricultural economy and craft activity such as textile production, but little metalwork or other wealth. A very different sort of site also existed in the Thames Valley, as at Runnymede Bridge, Surrey (Needham 1991). Here there was a site with a wooden piled waterfront, producing many bronze objects and other imports such as

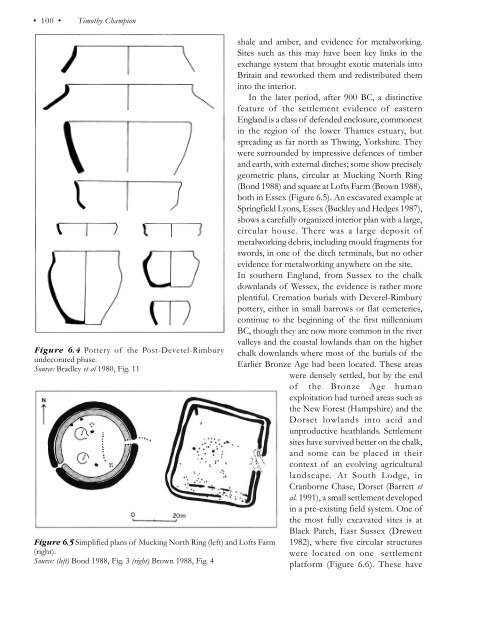

• 100 • Timothy Champion Figure 6.4 Pottery of the Post-Devetel-Rimbury undecorated phase. Source: Bradley et al 1980, Fig. 11 Figure 6.5 Simplified plans of Mucking North Ring (left) and Lofts Farm (right). Source: (left) Bond 1988, Fig. 3 (right) Brown 1988, Fig. 4 shale and amber, and evidence for metalworking. Sites such as this may have been key links in the exchange system that brought exotic materials into Britain and reworked them and redistributed them into the interior. In the later period, after 900 BC, a distinctive feature of the settlement evidence of eastern England is a class of defended enclosure, commonest in the region of the lower Thames estuary, but spreading as far north as Thwing, Yorkshire. They were surrounded by impressive defences of timber and earth, with external ditches; some show precisely geometric plans, circular at Mucking North Ring (Bond 1988) and square at Lofts Farm (Brown 1988), both in Essex (Figure 6.5). An excavated example at Springfield Lyons, Essex (Buckley and Hedges 1987), shows a carefully organized interior plan with a large, circular house. There was a large deposit of metalworking debris, including mould fragments for swords, in one of the ditch terminals, but no other evidence for metalworking anywhere on the site. In southern England, from Sussex to the chalk downlands of Wessex, the evidence is rather more plentiful. Cremation burials with Deverel-Rimbury pottery, either in small barrows or flat cemeteries, continue to the beginning of the first millennium BC, though they are now more common in the river valleys and the coastal lowlands than on the higher chalk downlands where most of the burials of the Earlier Bronze Age had been located. These areas were densely settled, but by the end of the Bronze Age human exploitation had turned areas such as the New Forest (Hampshire) and the Dorset lowlands into acid and unproductive heathlands. Settlement sites have survived better on the chalk, and some can be placed in their context of an evolving agricultural landscape. At South Lodge, in Cranborne Chase, Dorset (Barrett et al. 1991), a small settlement developed in a pre-existing field system. One of the most fully excavated sites is at Black Patch, East Sussex (Drewett 1982), where five circular structures were located on one settlement platform (Figure 6.6). These have

- Page 63 and 64: • 48 • Steven Mithen provided e

- Page 65 and 66: • 50 • Steven Mithen Attempts h

- Page 67 and 68: • 52 • Steven Mithen may reflec

- Page 69 and 70: • 54 • Steven Mithen seeds from

- Page 71 and 72: • 56 • Steven Mithen Pollard, T

- Page 73 and 74: Chapter Four The Neolithic period,

- Page 75 and 76: • 60 • Alasdair Whittle graves

- Page 77 and 78: • 62 • Alasdair Whittle resourc

- Page 79 and 80: • 64 • Alasdair Whittle Figure

- Page 81 and 82: • 66 • Alasdair Whittle other s

- Page 83 and 84: • 68 • Alasdair Whittle Figure

- Page 85 and 86: • 70 • Alasdair Whittle inter-

- Page 87 and 88: • 72 • Alasdair Whittle hundred

- Page 89 and 90: • 74 • Alasdair Whittle and els

- Page 91 and 92: • 76 • Alasdair Whittle Moffett

- Page 93 and 94: • 78 • Mike Parker Pearson diff

- Page 95 and 96: • 80 • Mike Parker Pearson Figu

- Page 97 and 98: • 82 • Mike Parker Pearson argu

- Page 99 and 100: • 84 • Mike Parker Pearson Late

- Page 101 and 102: • 86 • Mike Parker Pearson been

- Page 103 and 104: • 88 • Mike Parker Pearson Figu

- Page 105 and 106: • 90 • Mike Parker Pearson are

- Page 107 and 108: • 92 • Mike Parker Pearson Bron

- Page 109 and 110: • 94 • Mike Parker Pearson Elli

- Page 111 and 112: • 96 • Timothy Champion For the

- Page 113: • 98 • Timothy Champion Perhaps

- Page 117 and 118: • 102 • Timothy Champion Little

- Page 119 and 120: • 104 • Timothy Champion CRAFT,

- Page 121 and 122: • 106 • Timothy Champion solely

- Page 123 and 124: • 108 • Timothy Champion and re

- Page 125 and 126: • 110 • Timothy Champion range

- Page 127 and 128: • 112 • Timothy Champion Coles,

- Page 129 and 130: • 114 • Colin Haselgrove votive

- Page 131 and 132: • 116 • Colin Haselgrove Figure

- Page 133 and 134: • 118 • Colin Haselgrove Figure

- Page 135 and 136: • 120 • Colin Haselgrove ancill

- Page 137 and 138: • 122 • Colin Haselgrove East A

- Page 139 and 140: • 124 • Colin Haselgrove France

- Page 141 and 142: • 126 • Colin Haselgrove As in

- Page 143 and 144: • 128 • Colin Haselgrove distri

- Page 145 and 146: • 130 • Colin Haselgrove From 1

- Page 147 and 148: • 132 • Colin Haselgrove throug

- Page 149 and 150: • 134 • Colin Haselgrove Stead,

- Page 151 and 152: • 136 • W.S.Hanson Table 8.1 Ev

- Page 153 and 154: • 138 • W.S.Hanson country are

- Page 155 and 156: • 140 • W.S.Hanson eventually s

- Page 157 and 158: • 142 • W.S.Hanson Figure 8.4 S

- Page 159 and 160: • 144 • W.S.Hanson Figure 8.5 S

- Page 161 and 162: • 146 • W.S.Hanson Westerton, P

- Page 163 and 164: • 148 • W.S.Hanson Figure 8.8 A

• 100 • Timothy Champion<br />

Figure 6.4 Pottery <strong>of</strong> the Post-Devetel-Rimbury<br />

undecorated phase.<br />

Source: Bradley et al 1980, Fig. 11<br />

Figure 6.5 Simplified plans <strong>of</strong> Mucking North Ring (left) and L<strong>of</strong>ts Farm<br />

(right).<br />

Source: (left) Bond 1988, Fig. 3 (right) Brown 1988, Fig. 4<br />

shale and amber, and evidence for metalworking.<br />

Sites such as this may have been key links in the<br />

exchange system that brought exotic materials into<br />

<strong>Britain</strong> and reworked them and redistributed them<br />

into the interior.<br />

In the later period, after 900 BC, a distinctive<br />

feature <strong>of</strong> the settlement evidence <strong>of</strong> eastern<br />

England is a class <strong>of</strong> defended enclosure, commonest<br />

in the region <strong>of</strong> the lower Thames estuary, but<br />

spreading as far north as Thwing, Yorkshire. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

were surrounded by impressive defences <strong>of</strong> timber<br />

and earth, with external ditches; some show precisely<br />

geometric plans, circular at Mucking North Ring<br />

(Bond 1988) and square at L<strong>of</strong>ts Farm (Brown 1988),<br />

both in Essex (Figure 6.5). <strong>An</strong> ex<strong>ca</strong>vated example at<br />

Springfield Lyons, Essex (Buckley and Hedges 1987),<br />

shows a <strong>ca</strong>refully organized interior plan with a large,<br />

circular house. <strong>The</strong>re was a large deposit <strong>of</strong><br />

metalworking debris, including mould fragments for<br />

swords, in one <strong>of</strong> the ditch terminals, but no other<br />

evidence for metalworking anywhere on the site.<br />

In southern England, <strong>from</strong> Sussex to the chalk<br />

downlands <strong>of</strong> Wessex, the evidence is rather more<br />

plentiful. Cremation burials with Deverel-Rimbury<br />

pottery, either in small barrows or flat cemeteries,<br />

continue to the beginning <strong>of</strong> the first millennium<br />

BC, though they are now more common in the river<br />

valleys and the coastal lowlands than on the higher<br />

chalk downlands where most <strong>of</strong> the burials <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Earlier Bronze Age had been lo<strong>ca</strong>ted. <strong>The</strong>se areas<br />

were densely settled, but by the end<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Bronze Age human<br />

exploitation had turned areas such as<br />

the New Forest (Hampshire) and the<br />

Dorset lowlands into acid and<br />

unproductive heathlands. Settlement<br />

sites have survived better on the chalk,<br />

and some <strong>ca</strong>n be placed in their<br />

context <strong>of</strong> an evolving agricultural<br />

lands<strong>ca</strong>pe. At South Lodge, in<br />

Cranborne Chase, Dorset (Barrett et<br />

al. 1991), a small settlement developed<br />

in a pre-existing field system. One <strong>of</strong><br />

the most fully ex<strong>ca</strong>vated sites is at<br />

Black Patch, East Sussex (Drewett<br />

1982), where five circular structures<br />

were lo<strong>ca</strong>ted on one settlement<br />

platform (Figure 6.6). <strong>The</strong>se have