private client legal brief - Mackrell International

private client legal brief - Mackrell International

private client legal brief - Mackrell International

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

PRIVATE CLIENT<br />

LEGAL BRIEF<br />

In this first of a series of articles on the overseas aspects of English estate planning, Andrew<br />

Jones considers the position of the English ex-pat.<br />

When an English person buys a home overseas, his or her affairs can become a whole lot<br />

more complicated, and need to be dealt with carefully. Misconceptions about the situation<br />

abound, and this article attempts to separate some of the myths from the reality.<br />

The biggest misconception I come across regularly is the assumption by ex-pats either:<br />

a. that because they are English, their assets will pass on their death under English law; or<br />

b. that because their assets are in (say) France, their assets will pass on their death under<br />

French law.<br />

Actually both assumptions are wrong and, if you think about it, they are inconsistent with one<br />

another as well. The important thing is not to make any rash assumptions, and to take advice<br />

on the actual situation. The real rule is, I’m afraid, rather more complicated than either of the<br />

above, and it is that:<br />

a. immovable assets (a term which more-or-less means the same as “real estate” – land and<br />

buildings) pass under the law of the jurisdiction where the asset is situated; but<br />

b. movable assets (any assets which are not immovable) pass under the law of the<br />

jurisdiction where the deceased is domiciled.<br />

A further complication is that many other jurisdictions do not have the same rule. This can<br />

lead to an overlap (England and the other jurisdiction both claiming that their law applies) or<br />

a gap (England and the other jurisdiction both claiming that the other law applies).<br />

Domicile is important for another reason also: the UK charges the worldwide estates of its<br />

domiciliaries to inheritance tax, but it only charges the UK-situated assets of nondomiciliaries<br />

to inheritance tax. With tax at a flat 40% on all assets over £325,000, this can<br />

make a huge difference.<br />

That brings us to the very important question: what does domicile mean? I will have much<br />

more to say about domicile in the subsequent articles in this series, but in summary:<br />

a. Everybody has one, and only one, domicile at any one time.<br />

b. When you are born, your domicile is the domicile of your father at the time of your birth<br />

(except that illegitimate children take their mother’s domicile). This is called a domicile<br />

of origin.<br />

c. The domicile of origin is “sticky” – if at any time you do not have another domicile then<br />

your domicile of origin prevails. This can produce odd results (since it is possible in<br />

theory for your domicile of origin to be somewhere you have never been!) but can also<br />

produce unfortunate results, from a tax viewpoint, especially for those whose domicile of<br />

origin is English.

d. You acquire a new domicile by making a jurisdiction your domicile of choice. To do so<br />

you have to be physically residing there and have the intention of remaining there<br />

permanently. This question of intention is one of objective fact: merely declaring “my<br />

domicile is so-and-so” (e.g. in your will) is not nearly good enough, although it can<br />

certainly help. Many people have had their domicile successfully challenged by their<br />

families or by the tax authorities. There are a large number of factors, called “badges of<br />

domicile”, which judges use to establish what your true domicile is.<br />

Next, we come to the deemed domicile rules. These are rules that keep you in the UK’s<br />

inheritance tax net for longer than would otherwise be the case, by saying that if you were:<br />

a. tax resident in the UK for 17 of the last 20 tax years; or<br />

b. domiciled in the UK at any time in the last three years;<br />

then you will be treated as if you were a UK domiciliary for inheritance tax purposes.<br />

One common problem, in my experience, is that the deemed domicile rules are better known<br />

than the actual domicile rules by international <strong>client</strong>s (and sometimes by their advisers) – and<br />

perhaps this is because they are easier to understand and are far less woolly. It is therefore<br />

very important to avoid the misconception that the deemed domicile rules are the rules: they<br />

are not – they are just a limited extension to the rules and they apply for one purpose only,<br />

namely to catch some people in the inheritance tax net who would otherwise escape it. Take<br />

care to avoid that misconception: deemed domicile can only entangle you in the net, it cannot<br />

release you from it; deemed domicile does not apply to any of the other taxes, only<br />

inheritance tax; deemed domicile has no effect whatsoever on succession or family law.<br />

Throughout this article, “England” means “England and Wales”. The law of England and the<br />

law of Wales are the same in this respect: they are one jurisdiction, so moving across that<br />

border has no more effect than moving from Hertfordshire to Hampshire. However, it is not<br />

always widely realised that Scotland and Northern Ireland are different jurisdictions: so this<br />

article does apply to an English person who moves to either of them – the only real difference<br />

being that he or she will have moved to a jurisdiction which also has UK inheritance tax.<br />

This problem – that somewhere which you or I might think of as one country is actually<br />

divided into several jurisdictions – is quite common. Each state of the USA is a separate<br />

jurisdiction, for example. So is each canton of Switzerland. Canada and Australia are divided<br />

into a number of jurisdictions. This can affect the points analysed earlier in this article quite<br />

considerably. For example, moving to the USA and intending to stay there permanently, but<br />

not settling on a particular state, cannot give you a new domicile of choice.<br />

Andrew Jones is head of Private Client at the London office of <strong>Mackrell</strong> Turner Garrett. He<br />

can be contacted on 0207 240 0521 or at andrew.jones@mackrell.com<br />

MACKRELL TURNER GARRETT: PRIVATE CLIENT LEGAL BRIEF FOR NOVEMBER 2009. This note is intended for general guidance<br />

only, and not as a replacement for specific <strong>legal</strong> advice on the particular facts in every situation. Andrew Jones and <strong>Mackrell</strong> Turner<br />

Garrett do not accept responsibility for any action taken (or not taken) in reliance on this note. We are happy to give advice on individual<br />

situations, and usually do so in close consultation with <strong>legal</strong> advisers in the other jurisdiction(s) involved. <strong>Mackrell</strong> Turner Garrett is a<br />

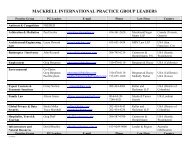

member of <strong>Mackrell</strong> <strong>International</strong>, a network of <strong>legal</strong> firms in many jurisdictions across the globe.