PDF, 4.37MB - Combat Law

PDF, 4.37MB - Combat Law

PDF, 4.37MB - Combat Law

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

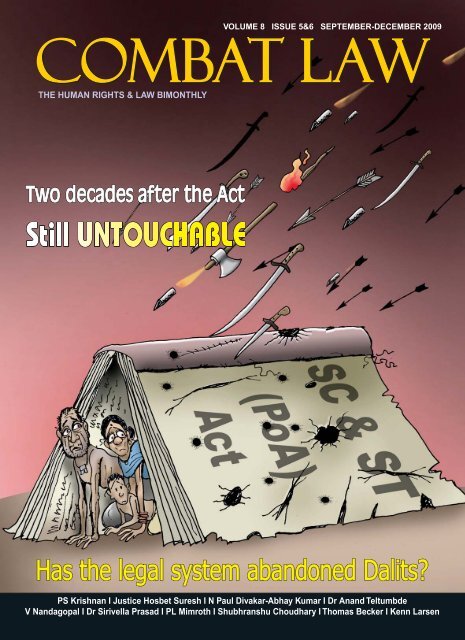

VOLUME 8 ISSUE 5&6 SEPTEMBER-DECEMBER 2009<br />

<br />

THE HUMAN RIGHTS & LAW BIMONTHLY<br />

<br />

Still UNTOUCHABLE<br />

Has the legal system abandoned Dalits?<br />

PS Krishnan I Justice Hosbet Suresh I N Paul Divakar-Abhay Kumar I Dr Anand Teltumbde<br />

V Nandagopal I Dr Sirivella Prasad I PL Mimroth I Shubhranshu Choudhary I Thomas Becker I Kenn Larsen

COMBAT LAW<br />

SEPTEMBER-December 2009<br />

VOLUME 8, ISSUE 5&6<br />

Editor<br />

Harsh Dobhal<br />

Senior Associate Editor<br />

Suresh Nautiyal<br />

Assistant Editor<br />

Neha Bhatnagar<br />

Cover Illustration<br />

Shyam Jagota<br />

Design<br />

Mahendra S Bora<br />

Asstt. Director, P&D<br />

Kamlesh S Rawat<br />

Deputy Manager, Circulation<br />

Hitendra Chauhan<br />

Editorial Office<br />

576, Masjid Road, Jangpura<br />

New Delhi-110014<br />

Phone : +91-11-65908842<br />

Fax: +91-11-24374502<br />

E-mail your queries and opinions<br />

to: editor@combatlaw.org<br />

lettertoeditor@combatlaw.org<br />

combatlaw.editor@gmail.com<br />

Website: www.combatlaw.org<br />

For subscription & circulation<br />

enquiries email to:<br />

subscriptions@combatlaw.org<br />

Phone: +91-09899630748<br />

Any written matter that is published in<br />

the magazine can be used freely with<br />

credits to <strong>Combat</strong> <strong>Law</strong> and the author.<br />

In case of publication, please write to<br />

us at the above-mentioned address.<br />

The opinions expressed in the articles<br />

are those of the authors.<br />

Epic Shame<br />

Superiority and purity of race formed the polluting foundations of<br />

Nazism which was finally defeated by the logic of time and history.<br />

Slavery too, having had its run, was abolished. But the institution of<br />

caste has been determining a human being’s destiny for almost as long<br />

as India claims to be a civilisation. Till date, even the much rational,<br />

educated citizen of India has been deriving sanction from it to exclude<br />

and discriminate against a community, known as lower castes or ‘Dalits’,<br />

finding themselves at the bottom of a cruel Indian caste system.<br />

Many of them treated as untouchables, they are denied basic dignity<br />

of life, fundamental human rights, civil liberties, rightful opportunities<br />

to develop, advance and make informed choices in life. Violence in all its<br />

forms is perpetrated against them – physical, psychological, cultural<br />

and economic. Even our claim to educating them has not been able to lift<br />

the Dalits out of their centuries of miserable conditions as much as the<br />

education has failed to enlighten and liberate the minds of the so-called<br />

upper castes and purge them of caste prejudices. Even today, over onesixth<br />

of India’s population, roughly some 170 million people, live a precarious<br />

existence, shunned by Indian society.<br />

After gaining Independence, India embarked on quite a progressive<br />

journey towards enacting a plethora of progressive legislations to uplift<br />

various marginalised communities. With regard to Dalits, we have had<br />

The Protection of Civil Rights Act, 1955, The Bonded Labour System<br />

(Abolition) Act, The Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act,<br />

1986 and the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of<br />

Atrocities) Act, 1989, among others.<br />

It has been two decades when the SC/ST (PoA) Act was passed aiming<br />

at eliminating atrocities against Dalits with provisions for protection,<br />

compensation and rehabilitation of the victims of caste bias and punishment<br />

for perpetrators of violence. But, like all other progressive legislations,<br />

this law also has served more of a decorative purpose on paper<br />

than giving desirable effects to the rights envisaged in the Act. The<br />

implementation of the SC/ST (PoA) Act, due to shoddy investigations<br />

by all pervasive upper caste mindset, remains abysmally weak even on<br />

its 20th anniversary.<br />

If we have a look at the available data, more than 62,000 human<br />

rights violations are recorded against Dalits annually, with an average of<br />

two Dalits assaulted every hour, two murdered and at least an equal<br />

number tortured or burned every day. There are millions of SC/ST children<br />

working as child labour. About 80 to 90 percent Dalits who work as<br />

bonded labour do so in order to pay off their debt while about an estimated<br />

800,000 are still engaged in manual scavenging. Dalit women in<br />

India face triple burden of caste, class and gender with an average of<br />

three Dalit women and children raped every day.<br />

Judiciary is generally considered to be the last ray of hope for the dispossessed<br />

and victimised. However, the conviction rate of crimes<br />

against Dalits is abysmally low at only about 2.31% while the number<br />

of acquittal is six times more. Over 70% cases are still pending. This is<br />

not to suggest that the Act has not resulted in helping the cause of Dalits<br />

but the results are far from desirable. The problem does not lie with the<br />

law alone. Apart from social awareness and education to change the<br />

anti-Dalit mindset, we perhaps need more teeth to the law, provisions<br />

for a better implementation and stringent actions against violators.<br />

This issue of <strong>Combat</strong> <strong>Law</strong> takes this as an opportunity to review the<br />

20 years of the PoA Act, with eminent experts and activists highlighting<br />

the shortcomings and recommending amendments to make the law<br />

more accountable and effective in an attempt to fight against all sources<br />

of discrimination, inequality and exclusion in pursuit of a more egalitarian<br />

social order.<br />

Photo courtesy: Websites & others<br />

Harsh Dobhal

C O N T E N T S<br />

DALIT RIGHTS<br />

6<br />

INTERVIEW<br />

32<br />

"Empower Dalits for<br />

Empowering India"<br />

Retrospect and Prospect<br />

The PoA Act, now two decades old, was enacted to protect<br />

Dalits from wanton attacks by the upper castes, but the<br />

law has not achieved desirable results<br />

–PS Krishnan<br />

A bureaucrat-cum-crusader<br />

of Dalit cause, PS<br />

Krishnan has always been<br />

behind-the-scene of the<br />

historical initiatives that<br />

have positively impacted<br />

millions of Dalits in India<br />

44<br />

38<br />

Right not to<br />

be treated as<br />

untouchable<br />

Khairlanji: Whither the atrocity Act?<br />

If the justice delivery system is blind to the social reality of<br />

caste, the entire exercise of creating the constitutional<br />

structure and laws for protecting Dalits becomes selfdefeating<br />

–Dr Anand Teltumbde<br />

There is an urgent need<br />

to redraft Article 17 in<br />

the form of a right -<br />

'right not to be treated<br />

as an untouchable'<br />

–Justice (Retd) H. Suresh<br />

48 59<br />

A neglected component<br />

In the last five years, the system has denied SCs a whopping<br />

sum of Rs 76,690 crore that should have been earmarked<br />

for them under the special component plan<br />

–N Paul Divakar & Abhay Kumar<br />

Tardy implementation in Rajasthan<br />

The affected groups experience violence on daily basis and<br />

the deterrence envisaged in the laws especially enacted for<br />

this purpose is not in evidence.<br />

–PL Mimroth<br />

2<br />

COMBAT LAW SEPTEMBER-DECEMBER 2009

C O N T E N T S<br />

DALIT RIGHTS<br />

62<br />

65<br />

An experiential review<br />

of SC/ST (PoA) Act<br />

Recommendations of Justice Punnaiah<br />

Commission<br />

The safeguards ensured by the Constitution have become<br />

merely "proclamation of theory" in the backdrop of nonimplementation<br />

of the laws meant for Dalit upliftment<br />

–Imran Ali<br />

Dignity of life and equal<br />

opportunities to Dalits are<br />

distant dreams despite 20<br />

years of enactment of<br />

SC/ST (PoA) Act<br />

–V Nandagopal<br />

67<br />

PRISONERS' ABUSE<br />

69<br />

Dalit laws: Mere<br />

paper tigers?<br />

Across India, the SC/ST<br />

(PoA) Act is operating<br />

more in defiance than<br />

in compliance. A<br />

ground reality report<br />

from Gujarat<br />

Condemned Twice<br />

Various forms of abuse by prison staff and other inmates<br />

have become a common feature in the lives of those incarcerated<br />

women whose basic human rights stand violated<br />

while they serve a sentence<br />

–Leni Chaudhuri & Reena Mary George<br />

ADIVASIS<br />

73<br />

TRIBAL RIGHTS<br />

76<br />

Jharkhand's dispensable tribe<br />

After the police firing incident on the Adivasis near<br />

Kathikund in December 2008, the tribals want the government<br />

to cease its repression of the community and terminate<br />

the catastrophic project<br />

–Thomas Becker<br />

Lost world of Chakmas<br />

The ancient tribe of Chakmas today desperately needs to be<br />

uplifted from the depths it has been spurned into<br />

–Kenn Larsen<br />

www.combatlaw.org 3

C O N T E N T S<br />

ENVIRONMENT<br />

Haunting Beauty<br />

of the Ghats<br />

JUDGEMENT<br />

HIV/AIDS: HC brings<br />

hope to many<br />

81<br />

The book captures the<br />

diversity of the Western<br />

Ghats or Sahyadri even as<br />

the volume examines the<br />

ecological wounds caused<br />

by the greedy<br />

–Suresh Nautiyal<br />

82<br />

In a landmark judgement<br />

that has wide implications,<br />

the Bombay HC has ordered<br />

free of cost second line<br />

treatment to persons living<br />

with HIV/AIDS, thus bringing<br />

a sigh of relief to many who<br />

were not responding to<br />

first-line therapy<br />

FARMERS' SUICIDE<br />

83<br />

Farmer graveyard?<br />

On an average, four farmers<br />

kill themselves everyday, in<br />

this Re 1 rice land!<br />

–Shubhranshu Choudhary<br />

VILLAGE COURTS<br />

Speedy justice<br />

at grassroots<br />

A superficial view may<br />

create a misconception<br />

that the Gram Nyayalaya<br />

and Nyaya Panchayat are<br />

competing entities, but a<br />

closer look shows they<br />

are totally different in<br />

their approach<br />

84<br />

86<br />

DOMESTIC WORKERS<br />

Domestic worker in a hostile world<br />

88<br />

WORDS & IMAGES<br />

Thorny journey<br />

to justice<br />

Ending up as domestic servants, in the<br />

absence of any legal mechanism to protect<br />

their rights they not only face harassment<br />

at the hands of their employers but<br />

also become victims of abuse by placement<br />

agencies<br />

Somehow off-the-track book,<br />

"<strong>Law</strong> & Life" by Justice VR<br />

Krishna Iyer throws light on<br />

complex and multiple aspects<br />

of the justice delivery system<br />

in India<br />

–Anisha Mitra & Karelia Rajagopal<br />

–Suresh Nautiyal<br />

90<br />

91<br />

92<br />

Narrating evolution<br />

of Indian politics<br />

The book is an attempt to fill an important<br />

space -- a journalistic, non-academic<br />

pedagogical narrative for students who<br />

wish to explore the contours of the evolution<br />

of politics in independent India<br />

Interpreting the<br />

Interpretation<br />

The book presents interplay of concepts<br />

like 'social context', 'understanding', and<br />

varying forms of 'genre' when assessing<br />

the media-audience correlation<br />

Capturing systemic<br />

violence against Dalits<br />

The documentary is a moving narrative<br />

of systemic violation of the rights of the<br />

Dalits in a society where caste prejudices<br />

continue determining social, economic<br />

and political reality of millions<br />

–Hormazd Mehta<br />

–Rosie Rogers<br />

–Keya Advani<br />

4<br />

COMBAT LAW SEPTEMBER-DECEMBER 2009

The role you play!<br />

Dear editor,<br />

In order to manipulate law, the principle<br />

of jurisprudence that a person<br />

is presumed to be innocent till<br />

proved guilty in a court is being<br />

invoked to shield tainted politicians.<br />

The presumption of innocence<br />

relates to a routine criminal offence<br />

and not to unbecoming conduct of a<br />

person holding public office.<br />

Conduct amounting to a wrongdoing<br />

justifies a prohibition from holding<br />

public office. In the case of a government<br />

servant accused of serious<br />

misconduct he is met with suspension<br />

till his case goes through a disciplinary<br />

inquiry and later to court.<br />

In line with this suspension from<br />

service in case of government servants<br />

there has to be a bar to holding<br />

public office for elected representatives<br />

till the outcome of the cases<br />

against them is revealed. The ministers<br />

should not hold office once an<br />

FIR is registered against them more<br />

so a chargesheet. They will misuse<br />

their power and authority to manipulate<br />

their trial. This is exactly what<br />

has happened in the case of Goa<br />

health minister Vishwajit Rane<br />

whom Goa police claimed could not<br />

be traced for almost two months to<br />

serve him court summons. As<br />

emphasised by Prime Minister Dr<br />

Manmohan Singh the standard for<br />

those in public life should be that not<br />

only Caesar, but even Caesar's wife<br />

should be above suspicion!<br />

–Aires Rodrigues<br />

Ribandar, Goa<br />

L E T T E R S<br />

Manipur is 'money put'<br />

Dear editor,<br />

Where is the jewel of India? This<br />

question lies in the labyrinth of injustice<br />

done to one and all in the state of<br />

Manipur. Everyday, on an average<br />

three men are allegedly killed in the<br />

north-eastern state resulting close to<br />

1,095 male deaths due to factors best<br />

known to the deceased or the killers.<br />

Within a span of few years, the malefemale<br />

ratio will go down so much<br />

giving a negative trend in the<br />

demography. The oversized female<br />

population in Manipur has resorted<br />

to unethical means for livelihood.<br />

Khwairamband Bazaar, which is<br />

overcrowded with women who<br />

return home with few kgs of rice<br />

each evening in a worn out jeep, is<br />

just the tip of the iceberg. Where is<br />

the Sanaleibak (golden land) in this<br />

scene? The male youth in the age<br />

group 25-38 years has to suffer a lot<br />

in the struggle for existence. With job<br />

giving institution becoming meagre,<br />

a day will come when no youth<br />

remains in Manipur as 90 percent of<br />

them will move to other states and<br />

undertake inhuman jobs/labour only<br />

for the target of existence. There is no<br />

question that girls, on the other hand<br />

will not stay idle. One of the realistic<br />

trends which has cropped in<br />

Manipur is: One girl will get herself<br />

married to a man under circumstances.<br />

She will stay for some time<br />

and return back to her maternal<br />

home under lie-filled pretexts. Later<br />

when such deserted man marries<br />

other girls, the first girl will resort to<br />

"Izzat dabi" to the man. It won't be<br />

wrong to mention that parents possessing<br />

daughters are making booms<br />

of money by the above mentioned<br />

tactics. A well known joke in<br />

Manipur is "percentage". There is a<br />

percentage culture right from a plate<br />

of rice (chakluk) to a contract done<br />

by any agency. As long as this culture<br />

exists no planning and development<br />

can take place. The epoch of "chahi<br />

chatret khuntakpa" (seven hundred<br />

devastation) has already begun. Life<br />

filled with "Ex-gratia, Izzat Dabi",<br />

corruptions in all spheres coupled<br />

with "no utilisation certificates" are<br />

the azure gems which are engraved<br />

in this Sanaleibak- the golden land.<br />

–Michael Khumancha<br />

by e-mail<br />

An eye opener Special<br />

Dear editor,<br />

<strong>Combat</strong> <strong>Law</strong> magazine's Special<br />

Supplement 2009 (Fake Encounters:<br />

How they are done) that carries the<br />

extracts of the report of the<br />

metropolitan magistrate, court-1 at<br />

Ahmedabad vis-à-vis killing of<br />

Ishrat Jehan and others, is an eye<br />

opener not only for the judiciary but<br />

also for media and the sane voices. It<br />

was shocking to learn that the<br />

accused were taken into custody<br />

and then killed in cold blood. This<br />

shows how crudely and bluntly our<br />

system works. It also shows that in a<br />

democracy like ours no stone is left<br />

unturned to make mockery of the<br />

democratic values, not to mention<br />

the human rights. Our leaders talk<br />

very loud about our democracy at<br />

the global fora and portray India as<br />

a secular, multi-religious and multiethnic<br />

nation with diverse valuesystems<br />

and ethos. These leaders<br />

also want a permanent seat on the<br />

UN Security Council. However,<br />

question is: Can these leaders look<br />

into their hearts first and then<br />

talk about the human rights and<br />

secularism?<br />

I agree with the editorial of the<br />

magazine that the report has scientific<br />

elements in it and truly a beacon<br />

light for other judicial officers conducting<br />

similar enquiries.<br />

True democracy is one of the best<br />

forms of governance till today and in<br />

such a system the police and security<br />

forces should have no licence at all to<br />

kill anybody. The laws like AFSPA<br />

give such licences and the time is ripe<br />

to do away with such draconian laws<br />

at the earliest.<br />

–Natasha N<br />

LLB, IInd year<br />

University of Delhi<br />

www.combatlaw.org 5

DALIT RIGHTS<br />

In their homelands<br />

their life is a daily<br />

struggle to be treated<br />

with the minimum<br />

dignity as normal<br />

human beings - a<br />

battle in which all<br />

odds are stacked<br />

against them and<br />

which they have been<br />

and still are losing.<br />

The PoA Act, now two<br />

decades old, was<br />

enacted to protect the<br />

SCs and STs from<br />

wanton attacks by<br />

those claiming to be<br />

superior. But the law<br />

has not achieved<br />

desirable results to<br />

reduce the number of<br />

crimes against them,<br />

including murders and<br />

rapes, and the<br />

conviction rates are<br />

dismally low, writes<br />

PS Krishnan as he<br />

critically analyses<br />

atrocities committed<br />

on a community<br />

springing from the<br />

centuries old<br />

caste bias<br />

ATROCITIES AGAINST DALITS<br />

Retrospect<br />

and Prospect<br />

Atrocities against scheduled<br />

castes (SCs) and scheduled<br />

tribes (STs) and untouchability<br />

are the natural expressions of the<br />

unnatural Indian caste system (ICS).<br />

Therefore, a clear understanding of<br />

the age-old phenomenon of<br />

“untouchability”, which is an integral<br />

part and essential feature of the<br />

ICS and of the recent phenomenon of<br />

atrocities, can only be facilitated by a<br />

brief overview of the ancient caste<br />

bias and how it works in relation to<br />

the SCs and STs and also socially and<br />

educationally backward classes (also<br />

known as backward classes or other<br />

backward classes and hereafter<br />

briefly referred to as BCs). The usual<br />

6<br />

COMBAT LAW SEPTEMBER-DECEMBER 2009

DALIT RIGHTS<br />

descriptions and interpretations of<br />

the caste system, which are but of<br />

course upper caste-centric, do not<br />

bring out the essence of its nature<br />

and functions. In order to perceive<br />

that essence, it is necessary to study it<br />

from the standpoint of the large<br />

majority of the Indian people, who<br />

have been its victims in various<br />

forms and degrees, and to understand<br />

how the caste system works in<br />

relation to the SCs, STs and the BCs.<br />

Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar was the<br />

first thinker to bring a fresh approach<br />

to the examination of the essence and<br />

functioning of the caste system in<br />

India. Contrary to earlier and later<br />

practice, he focused attention on<br />

labourers in relation to the caste system.<br />

He identified its important features<br />

by characterising it as:<br />

“A division of labourers into<br />

water tight compartments” and as<br />

“an hierarchy” in which the division<br />

of labourers is graded one above the<br />

other. He further refers to this as “a<br />

stratification of occupations”.<br />

Justice Chinnappa Reddy felicitously<br />

and appropriately called caste<br />

a system of “gradation & degradation”<br />

in his judgement in the Vasanth<br />

Kumar case of 1985 [1985 Supp<br />

SCC: 714]<br />

Looking at the Indian society in<br />

relation to its socio-economic frame<br />

and from the viewpoint of SCs, STs<br />

and BCs, I consider it realistic and<br />

enlightening to distinguish four layers<br />

of castes — very different from<br />

the traditional four Varnas model.<br />

The traditional Varna model is flawed<br />

for various reasons. For one, through<br />

this model the privileged minority<br />

has appropriated for itself threefourths<br />

or even more of the conceptual<br />

space, relegating the majority to<br />

the residual space characterising it as<br />

Shudra, and leaving no space at all for<br />

another substantial part of the population<br />

who were characterised as a<br />

Varnas. This model and the literature<br />

that has drawn on this model focus<br />

on concepts like “pollution” and<br />

“purity” which are terms coined by<br />

the privileged category to justify its<br />

privilege and the deprivation of others<br />

and they only help to obfuscate<br />

the functional reality of the Indian<br />

caste system. Its greatest deficiency is<br />

that it does not bring out the castebased<br />

exploitation which was its core<br />

essence. It also does not bring out its<br />

functional role of monopolisation of<br />

advantages and privileges by a<br />

minority of the population. The diagrammatic<br />

representation (see<br />

graph) of India’s traditional socioeconomic<br />

system and structure, still<br />

in operation and which was earlier<br />

expounded in my book Empowering<br />

Dalits for Empowering India 1 and elsewhere,<br />

depicts this clearly.<br />

The topmost layer is that of privilege<br />

and prestige. It consists of<br />

The colonial era and the<br />

post-Independence<br />

decades have no doubt<br />

introduced changes, but<br />

have not fundamentally<br />

altered the four-layer<br />

profile of the socioeconomic<br />

frame of nontribal<br />

India. Broadly<br />

speaking, most of the<br />

castes in the lowest<br />

layer have been<br />

classified as SCs for the<br />

purpose of measures of<br />

special protection and<br />

safeguards since 1935<br />

and also after<br />

Independence under a<br />

series of Presidential<br />

Orders issued in terms<br />

of Article 341 of the<br />

Constitution. They have<br />

been so classified on<br />

the basis of the criterion<br />

of “untouchability”.<br />

While the numerically<br />

large castes in this layer<br />

are typically agricultural<br />

labour castes (ALCs), to<br />

this layer should also be<br />

assigned a number of<br />

numerically small<br />

castes which are<br />

nomadic (N), seminomadic<br />

(SN) or<br />

“Vimukta Jati” (VJ) or<br />

“ex-criminal”. Some of<br />

them have also been<br />

classified as SCs on<br />

account of their being<br />

found to be victims of<br />

untouchability<br />

www.combatlaw.org<br />

7

DALIT RIGHTS<br />

A Diagrammatic Representation of India’s Traditional Socio-Economic Structure<br />

TOP LAYER<br />

Castes of Individuals/families in<br />

positions/occupations of privilege and prestige<br />

Almost Invariably forward/Advanced Castes<br />

MID-LAYER<br />

(Arrows show tendency to break loose<br />

from domination of and seek equal<br />

Castes of Peasants<br />

Generally SEBC/OBC<br />

Pastoral castes<br />

Castes of Artisans & Artisanal/Artisan-like<br />

Producers<br />

Almost Invariably SEBC/OBC<br />

Castes of those<br />

rendering services<br />

Lower Mid Layer<br />

Layer<br />

Bottom Layer<br />

Agricultural Labour Castes<br />

(Mostly SCs or Dalits)<br />

Tribes outside Tribal Areas (STs)<br />

Tribes of Scheduled Areas<br />

(STs)<br />

Very Backward Peasants of Very<br />

Backward “ethnic homelands”<br />

Parallel<br />

to<br />

Bottom<br />

Layer<br />

castes, to which all or the major proportion<br />

of persons in prestigious and<br />

privileged positions and occupations<br />

traditionally belong. Such traditional<br />

positions and occupations include<br />

religious/spiritual authority, state<br />

governance and public administration,<br />

control over agricultural land<br />

(irrespective of whether and when<br />

individual ownership came into existence<br />

in a region), military professions,<br />

commerce and the like. The<br />

second layer consists of land-owning<br />

and cultivating peasant castes. In<br />

relation to land, their traditional<br />

position was between land-controlling<br />

castes and agricultural labour<br />

castes. But, as a result of post-<br />

Independence land reforms, they<br />

have recently become land-controlling<br />

castes in some parts. Some of the<br />

peasant castes are also herders of cattle,<br />

sheep, goats etc. The third layer<br />

consists of two or three sub-layers —<br />

the castes of traditional artisans and<br />

the castes providing various personal<br />

services and pastoral castes. The lowest<br />

layer consists essentially of castes<br />

of agricultural labourers. The castes<br />

of the three lower layers have traditionally<br />

been producing primary and<br />

secondary goods and rendering various<br />

types of services and labour<br />

mainly for the top layer, on unequal<br />

terms in varying degrees and forms,<br />

and involving exploitation at various<br />

levels. This has been facilitated by<br />

the economic power of the top layer<br />

aided by the ideology of “caste-withuntouchability”,<br />

the latter part (i.e.,<br />

untouchability) being directed<br />

against the castes in the lowest layer.<br />

The colonial era and the post-<br />

Independence decades have no<br />

doubt introduced changes, but have<br />

not fundamentally altered the fourlayer<br />

profile of the socio-economic<br />

frame of non-tribal India. Broadly<br />

speaking, most of the castes in the<br />

lowest layer have been classified as<br />

SCs for the purpose of measures of<br />

special protection and safeguards<br />

since 1935 and also after independence<br />

under a series of Presidential<br />

Orders issued in terms of Article 341<br />

of the Constitution. They have been<br />

so classified on the basis of the criterion<br />

of “untouchability”. While the<br />

numerically large castes in this layer<br />

are typically agricultural labour<br />

castes (ALCs), to this layer should<br />

also be assigned a number of numerically<br />

small castes which are nomadic<br />

(N), semi-nomadic (SN) or “Vimukta<br />

Jati” (VJ) or “ex-criminal”. Some of<br />

them have also been classified as SCs<br />

on account of their being found to be<br />

victims of untouchability.<br />

To this layer also belong a number<br />

of scheduled tribes specified in a<br />

series of presidential orders issued in<br />

terms of Article 342 of the<br />

Constitution. While STs as a whole<br />

are outside the ambit of the Indian<br />

caste system and the bulk of them<br />

live in remote tribal areas, some of<br />

them have been sucked out of their<br />

homelands and have virtually<br />

become ALCs like the typical SCs.<br />

Some others represent tribes which<br />

never had a separate homeland and<br />

still others may be representatives of<br />

those submerged by the advancing<br />

caste-based agricultural civilisation<br />

of India. STs outside tribal areas live<br />

in style and circumstances which are<br />

little different from those of SCs and<br />

therefore logically belong to this, the<br />

lowest layer along with the SCs.<br />

Those N, SN & VJ communities<br />

which are neither SC nor ST are<br />

entered in BC lists. The castes in the<br />

second layer i.e., the mid-layer are<br />

8<br />

COMBAT LAW SEPTEMBER-DECEMBER 2009

DALIT RIGHTS<br />

generally found in BC lists. There are<br />

exceptions, which are logical and<br />

realistic. The presence of any caste of<br />

the top layer in BC lists is exceptional<br />

and such exceptions are either<br />

deliberately contrived aberrations or<br />

unrectified historical hangovers.<br />

STs in tribal areas — accounting<br />

for two-thirds to three-fourths of the<br />

scheduled tribe population of India<br />

— constitute a layer broadly parallel<br />

to the lowest layer and partly jutting<br />

above vaguely. This layer has nothing<br />

to do with the Panchama of/ outside<br />

the traditional four Varna model.<br />

The STs even in their homeland —<br />

though free from untouchability and<br />

the daily intrusion of and constant<br />

oppression of the caste bias — rank<br />

with SCs in the matter of all-round<br />

deprivation. In their homelands their<br />

life is a daily struggle to retain what<br />

they have against relentless external<br />

incursions — a battle in which all<br />

odds are stacked against them and<br />

which they have been and still are<br />

losing. Some of the N, SN and VJ categories<br />

have been included in the<br />

lists of STs on account of their possession<br />

of tribal characteristics.<br />

Among the main features and<br />

effects of the working of the Indian<br />

caste system through the centuries<br />

till date have been:<br />

(a) To lock up labourers as labourers,<br />

and agricultural labour castes as<br />

ALC.<br />

(b) Keep SCs down in their position<br />

with no or little scope for escape.<br />

(c) Keep STs grounded in remote<br />

areas except only to be drawn out to<br />

supplement labour requirements.<br />

SCs – as the<br />

greatest and<br />

most intensive,<br />

forced<br />

contributors of<br />

agricultural<br />

labour in India –<br />

have been central<br />

to this theme of<br />

exploitation and<br />

deprivation<br />

(d) To keep SC and ST in conditions<br />

of segregation and demoralisation<br />

and to deprive/minimise opportunities<br />

for their economic, educational<br />

and social advancement and upward<br />

mobility.<br />

(e) To Keep the backward classes tied<br />

down as providers of agricultural<br />

products (peasants), non-agricultural<br />

primary products (fisher-folk), traditional<br />

manufactured and processed<br />

products (artisans and skilled workers),<br />

service providers (hair-dressers)<br />

etc, on terms grossly adverse to them<br />

and hampering their economic, educational<br />

and social upliftment.<br />

(f) To retain a virtual monopoly over<br />

superior opportunities in the hands<br />

of a small elite drawn from the top<br />

layer of the traditional socio-economic<br />

system, by hampering, handicapping<br />

and hamstringing SCs, STs and<br />

BCs in different ways and to different<br />

degrees.<br />

SCs – as the greatest and most<br />

intensive, forced contributors of agricultural<br />

labour in India as well as<br />

other workforce, including labour of<br />

the most sordid and unpleasant type<br />

such as sanitation and death and cremation-related<br />

services – have been<br />

central to this theme of exploitation<br />

and deprivation. The agro-climatic<br />

characteristics of India, with the<br />

monsoon confined to a limited part<br />

of the year necessitating a large<br />

reserve of labour force based on the<br />

requirements for agriculture during<br />

short peak periods made it extremely<br />

important for the design and purpose<br />

of the caste system to ensure<br />

that the “untouchable” castes now<br />

classified as SCs were kept in a state<br />

of socio-economic incarceration<br />

without hope of redemption or<br />

escape. The coercive mechanism<br />

designed to secure this purpose has<br />

been:<br />

1. The caste system in its totality;<br />

2. Specifically against the scheduled<br />

castes, the instrumentality of<br />

untouchability over the centuries,<br />

which continues to this day with full<br />

virulence;<br />

3. For many centuries the Indian<br />

caste system was able to operate as<br />

the perfect instrument to keep the<br />

“untouchable” castes and plains<br />

tribes under total subjugation as<br />

providers of labour for agriculture<br />

and other purposes;<br />

4. The weapon of atrocities in the<br />

www.combatlaw.org 9

DALIT RIGHTS<br />

modern context when SCs have<br />

rejected the caste system ideology<br />

and psychology of subservience and<br />

thus the efficiency of untouchability<br />

as a disciplining instrument has been<br />

partly blunted.<br />

Emergence of “atrocities”<br />

The reformist, nationalist and revolutionary<br />

movements of the last one<br />

and a half centuries and the<br />

Ambedkarite movement have<br />

instilled a new sense of awareness in<br />

the Dalits. Under its influence they<br />

refuse to accept their status as<br />

ordained by the Indian caste system.<br />

This was given another dimension by<br />

the movement for land reforms, for<br />

reduction of crippling burdens on<br />

sharecropping tenants and for<br />

improvements in agricultural wages<br />

like the Telengana and Tebhaga<br />

agrarian movements and the agricultural<br />

labourers’ strikes in places like<br />

Thanjavur. It became necessary for<br />

the dominant classes drawn from<br />

upper castes in different parts of the<br />

country to forge new instruments of<br />

control. This is how atrocities, as we<br />

know them, made their debut on a<br />

large scale in the 60s. As the resistance<br />

of the Dalits has grown, so the<br />

frequency and brutal ferocity of<br />

atrocities have grown apace.<br />

Existential problems of SCs<br />

Along with an understanding of the<br />

Indian caste system in relation to<br />

Dalits, equally necessary for an<br />

understanding of untouchability and<br />

atrocities in their correct context and<br />

perspective is a picture of the existential<br />

conditions of SCs and STs,<br />

which continue to operate to this day<br />

even after nearly six decades of our<br />

glorious Constitution. No doubt<br />

there has been some amelioration of<br />

their conditions compared to the pre-<br />

Ambedkar, pre-Independence, pre-<br />

Constitution stage.<br />

The present existential conditions<br />

of SCs are marked and marred by the<br />

following features:<br />

(a) Landlessness and State’s failure to<br />

distribute land among all rural SC<br />

families<br />

(b) Lack of irrigation for and poor<br />

development of even the little land<br />

held by SCs<br />

(c) Condemnation of SCs to agricultural<br />

servitude and other hard labour<br />

with poor wages/remuneration<br />

(d) Condemnation to safai karamcharis<br />

or human scavenging<br />

(e) Subjection to rampant bonded<br />

labour<br />

(f) Denial of social security and modern<br />

facilities and conditions of work<br />

for the agricultural labour sector and<br />

the rest of the unorganised labour<br />

sector which accounts for 93 percent<br />

of the entire labour force of the country<br />

and among whom SCs, including<br />

those belonging to religious minorities<br />

(SCRM) are prominently placed.<br />

In addition, including socially and<br />

educationally backward classes<br />

belonging to religious minorities<br />

(SEdBCRM) and STs including those<br />

belonging to religious minorities<br />

(STRM) are also significantly present<br />

(g) Exclusion of majority of SC children<br />

from the main school system,<br />

which manifests itself as non-enrolment<br />

(including false enrolment),<br />

low rates of enrolment, high rates of<br />

dropouts (which partly is adjustment<br />

of false/formal enrolments) and low<br />

rate of survivors at the end of school.<br />

(h) Denial of quality education and<br />

denial of “level playing field” at<br />

every level of education — particularly<br />

at higher educational level.<br />

Failure to enact reservation in private<br />

educational institutions pursuant to<br />

the 93rd amendment of 2005 and following<br />

the successful defence and<br />

upholding by the Supreme Court of<br />

the Central Educational Institutions<br />

(Reservation in Admission) Act, 2006<br />

(i) Grabbing away in 2003 of funds<br />

provided in 1996 for establishing residential<br />

schools for quality education<br />

for SCs (also similar schools for STs<br />

and BCs)<br />

(j) Denial of access to market opportunities<br />

(k) Trivialisation, routinisation and<br />

truncation of special component plan<br />

(SCP) for scheduled castes, which<br />

was initiated about a quarter century<br />

back (in the late 1970s)<br />

(l) Poor outlays in the budgetary heads<br />

of welfare/ social justice ministry<br />

(m) Unsatisfactory implementation,<br />

quantitatively and qualitatively, of<br />

existing centrally sponsored schemes<br />

(CSS) and other existing developmental<br />

instrumentalities<br />

(n) Special problems of Nomadic,<br />

semi-Nomadic and Vimukta Jati, (formerly<br />

criminal) communities have<br />

missed attention. Their problems are<br />

different from those of the numerically<br />

large SC/ST/BC communities.<br />

(o) Nominations to national commissions<br />

for deprived categories are<br />

often made inappropriately, thereby<br />

crippling their functional efficiency<br />

and converting national commissions<br />

largely into national omissions.<br />

Gross delays in tabling of annual<br />

reports in Parliament and in public<br />

domain, defeat their purpose<br />

(p) Poor representation of SC, ST and<br />

SEdBCs in important bodies relevant<br />

to development and empowerment<br />

(q) Half-hearted implementation of<br />

reservation in central as well as state<br />

governments, PSUs, PSBs, universi-<br />

10<br />

COMBAT LAW SEPTEMBER-DECEMBER 2009

DALIT RIGHTS<br />

ties and leaving in the limbo bill for<br />

reservation for SCs and STs in the<br />

services of the State in order to provide<br />

statutory base and force for<br />

them<br />

(r) Tampering with and diluting preexisting<br />

reservation rules, including<br />

relegation of SCs and STs from the<br />

first and third positions in the pre-<br />

1977 roster to the seventh and thirteenth<br />

positions in 1977 by misinterpreting<br />

the Supreme Court judgement<br />

in the Sabharwal case<br />

(s) Denial of normal service benefits<br />

and progress to SCs<br />

(t) Denial of entry for SCs in technical,<br />

supervisory and managerial<br />

positions in the organised private<br />

sector till date<br />

(u) Depriving SCs of reservation in<br />

PSUs while privatising them and<br />

consequent reduction in number of<br />

reserved posts<br />

(v) Continuance of atrocities and<br />

practice of untouchability<br />

(w) Failure to establish Dalit-friendly<br />

administration at all levels and to<br />

adopt Dalit-friendly personnel policy<br />

Existential problems of STs<br />

Scheduled tribes share in common<br />

many of the existential problems of<br />

the SCs. However, following are<br />

some of the difficulties faced by the<br />

former exclusively:<br />

(i) Fraudulent and illegal dispossession<br />

of STs from their lands, often<br />

with implicit or even open collusion<br />

by those wielding power<br />

(ii) Consequent reduction of large<br />

numbers of STs into landless agricultural<br />

wage labourers<br />

(iii) Conversion of tribals into<br />

minorities in traditional tribal territories<br />

(iv) Depriving STs from their traditional<br />

rights in forests. The Indian<br />

Forest Act 1927, of colonial vintage,<br />

had been continued after independence<br />

till the Scheduled Tribes and<br />

other Traditional Forest Dwellers<br />

(Recognition of Forest Rights) Act<br />

was passed in December, 2006. But,<br />

the implementation of this Act is facing<br />

rough weather of late<br />

(v) Failure to reverse the process of<br />

shrinkage of non-timber forest produce<br />

or NTFP (minor forest produce<br />

or MFP), on which a large proportion<br />

of STs depend wholly or partly for<br />

their livelihood<br />

(vi) As part of the exploitation process,<br />

poor prices being paid by private<br />

merchants as well as governmental<br />

and cooperative agencies for<br />

NTFP/MFP collected by STs<br />

(vii) Displacement of STs from their<br />

lands and territories in the name of<br />

industries, mining, hydel plants, irrigation,<br />

township and other projects,<br />

the benefit of which accrues to nontribals<br />

and non-tribal territories,<br />

major proportion of project displaced<br />

persons (PDPs) are STs<br />

(viii) Displacement of tribal communities<br />

from their traditional common<br />

property survival resources through<br />

creation of national parks, sanctuaries<br />

and biosphere reserves<br />

(ix) Delayed formation of the second<br />

commission on the administration of<br />

the scheduled areas & welfare of STs<br />

under Article 339 (1), and lack of<br />

action on its report submitted by the<br />

commission to the government in<br />

Along with an<br />

understanding of the<br />

Indian caste system<br />

in relation to Dalits,<br />

equally necessary<br />

for an understanding<br />

of untouchability<br />

and atrocities in<br />

their correct context<br />

and perspective<br />

is a picture of the<br />

existential<br />

conditions of<br />

SCs and STs<br />

2004. Further lack of transparency<br />

regarding action proposed and failure<br />

in tabling the report in<br />

Parliament and placing it in public<br />

domain<br />

Atrocities against SCs and STs,<br />

along with untouchability against<br />

SCs, has to be seen as part of this<br />

large scheme of deliberate and comprehensive<br />

deprivation of SCs and<br />

STs against the socio-historical background<br />

of the caste system and its<br />

functioning; the inadequate efforts<br />

made by post-Independence and<br />

post-constitutional governance to<br />

terminate this evil and anti-national<br />

historical legacy, and the consequent<br />

present existential plight of the SCs<br />

and STs despite some amelioration<br />

after the Constitution. This applies in<br />

varying forms and varying extents to<br />

the backward classes. However, the<br />

present discussion is confined to SCs<br />

and STs as they constitute the worst<br />

victims of the inherited system,<br />

which is largely continuing, and the<br />

victims of atrocities are mainly the<br />

SCs and along with them, to a lesser<br />

extent, the STs.<br />

Antecedents of PCR Act<br />

Before Constitution of India, 1950<br />

The following, in brief, were the pre-<br />

Constitution immediate antecedents<br />

of the Act:<br />

● Exposure of untouchability and its<br />

wide ramifications as the Achilles’<br />

Heel of the Indian society and the<br />

projected Indian polity by Dr<br />

Babasaheb Ambedkar at the round<br />

table conferences.<br />

● Negotiations between Mahatma<br />

Gandhi and other Congress leaders<br />

with Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar in the<br />

Yeravda prison following Gandhi’s<br />

fast against the Macdonald Award in<br />

September 1924, the Mahatma-<br />

Babasaheb dialogue culminating in<br />

the Yeravda Pact.<br />

● Consequent sensitisation of the<br />

nationalist movement and the Indian<br />

National Congress to untouchability<br />

and the injustices done to the SCs —<br />

its adoption of removal of untouchability<br />

as a major plank.<br />

● Enactment of the Madras Removal<br />

of Civil Disabilities Act, 1938 by the<br />

popular government of the Congress<br />

in Madras Presidency led by Rajaji.<br />

● Similar enactments in many other<br />

provinces and princely states in the<br />

years shortly before or after independence<br />

and before the Constitution of<br />

India was adopted.<br />

Under Constitution of India, 1950<br />

● The watershed of Article 17 of independent<br />

India’s Constitution adopted<br />

in 1950 reads: “17. Abolition of<br />

untouchability – untouchability is<br />

abolished and its practice in any<br />

form is forbidden. The enforcement<br />

of any disability arising out of<br />

untouchability shall be an offence<br />

punishable in accordance with law.”<br />

● Enactment of the Untouchability<br />

www.combatlaw.org 11

DALIT RIGHTS<br />

(Offences) Act, 1955 w.e.f. from 01-<br />

06-1955, followed by immediate realisation<br />

of weaknesses of the Act.<br />

● Consequent introduction of the<br />

Untouchability (Offences) Act<br />

amendment and Miscellaneous<br />

Provisions Bill in Lok Sabha in 1972<br />

and its passing in 1976 as the<br />

Protection of Civil Rights Act, 1955<br />

with stronger, but still inadequate,<br />

provisions with effect from<br />

19.11.1976.<br />

Antecedents of PoA Act<br />

In modern times, atrocities can be<br />

traced back to the 19th century in<br />

parts of India when the discipline of<br />

untouchability began to be challenged<br />

by the “untouchables”. A<br />

committee which toured British<br />

India in 1920s for review of the working<br />

of the Government of India Act,<br />

1919 noted that many atrocities were<br />

being committed during those days<br />

against the untouchables but were<br />

going unnoticed and unpunished<br />

because no witness would come forward<br />

to give evidence. Dr Ambedkar,<br />

then MLC of Bombay, cited some<br />

early instances of atrocities against<br />

Dalits in Annexure A to the statement<br />

submitted by him to the Indian statutory<br />

commission (Simon<br />

Commission) on behalf of the<br />

Bahishkrita Hitakarini Sabha on<br />

29.05.1928, including the rioting and<br />

mass assaults on Dalits on 20.03.1927<br />

for asserting their right to drinking<br />

water from the public chowdar tank<br />

in Mahad, Kolaba district; and the<br />

mass assaults on and burning down<br />

of the dwellings of Balai people (SC)<br />

in Indore district. The early postindependence<br />

signal of the<br />

Ramanathapuram riots of 1957 starting<br />

with the assassination of the<br />

young educated Dalit leader<br />

Emmanuel for daring to defy<br />

untouchability-based interdicts on<br />

SCs did not register on the national<br />

radar though the state government<br />

took strong measures to quell the<br />

attacks on SCs. Under pressure of<br />

Dalit MPs, the government started<br />

monitoring atrocities from 1974, and<br />

in the case of STs 1981 onwards with<br />

special focus on murder, rape, arson<br />

and grievous hurt.<br />

There was a flare up of atrocities<br />

in and from 1977 onwards. The then<br />

home minister in defence, apparently<br />

to show that atrocities were not as<br />

serious as claimed, advanced the<br />

strange and shocking argument that<br />

the number of SC victims of atrocities<br />

was less than 15 percent, perhaps<br />

without understanding the implication<br />

of that argument that the SCs’<br />

due share in this is equal to their<br />

population percentage (though their<br />

entitlement to this share in landownership,<br />

national wealth, etc. were not<br />

recognised). The outcry that followed<br />

persisted resulting in a cabinet<br />

Atrocities can be<br />

traced back to the<br />

19th century in parts<br />

of India when the<br />

discipline of<br />

untouchability began<br />

to be challenged by<br />

the “Untouchables”.<br />

A committee which<br />

toured British India in<br />

1920s for review of the<br />

working of the<br />

Government of India Act,<br />

1919 noted that many<br />

atrocities were being<br />

committed during those<br />

days against the<br />

untouchables but were<br />

going unnoticed and<br />

unpunished<br />

reshuffle. At that time the government<br />

created the post of a joint secretary<br />

in the ministry of home affairs in<br />

charge of the subject of scheduled<br />

castes and backward classes including<br />

atrocities. I volunteered for this<br />

post and took up on top priority the<br />

task of monitoring of atrocities which<br />

I converted from mere receipt and<br />

transmission of statistical information,<br />

additionally into an active pursuit<br />

of individual gruesome incidents<br />

like Belchi, Bodh Gaya, Chainpur,<br />

Marathwada, Chikkabasavanahalli,<br />

Indravalli, etc. to their logical conclusion.<br />

The second important task was<br />

getting special courts with special<br />

judges for specific cases established<br />

by state governments, supported by<br />

carefully chosen special prosecutors<br />

and securing quick trials and execution<br />

of verdict without delay. In these<br />

efforts, I gratefully recall the total<br />

support of Dhaniklal Mandal, the<br />

then minister of state for home<br />

affairs. I continued this practice after<br />

the regime change in 1980 and similarly<br />

covered the atrocities at Pipra,<br />

Kafalta, Jetalpur, etc. This produced<br />

a crop of convictions and punishments<br />

including death sentences in<br />

Belchi.<br />

Atrocities continued with rising<br />

ferocity and frequency as basic contradictions,<br />

vulnerabilities and causative<br />

factors were evaded by the State at<br />

national and state levels for obvious<br />

reasons and treatment was mainly<br />

symptomatic and palliative instead of<br />

the required radical solutions.<br />

Under continued pressure of<br />

Dalit MPs and leaders, magnitude<br />

and gravity of problem was finally<br />

recognised by prime minister Rajiv<br />

Gandhi and he announced from the<br />

Red Fort in his Independence<br />

address on August 15, 1987 that an<br />

Act would be passed, if necessary, to<br />

check atrocities. I was called back<br />

from the state and appointed as special<br />

commissioner for SCs.<br />

After intensive consultations the<br />

PoA Act emerged in September 1989<br />

but not operationalised immediately<br />

under section 1 (3). I recall the active<br />

interest and support of Dr. B<br />

Shankaranand and the then home<br />

minister Buta Singh, particularly to<br />

my view that a new and stringent Act<br />

is necessary and it is not enough if<br />

the PCR Act is amended for this purpose<br />

as suggested by the ministry of<br />

welfare then.<br />

In my capacity as secretary, ministry<br />

of welfare, I took the initiative<br />

to quickly operationalise the Act<br />

w.e.f. January 30, 1990, after urgent<br />

consultations with state governments<br />

in order to swiftly cut the<br />

Gordian knot.<br />

Impact of PoA Act<br />

The Act came as a watershed in the<br />

jurisprudence of protection for the<br />

SCs and STs and their better coverage<br />

by the right to life under Article 21 as<br />

creatively interpreted from time to<br />

time by India’s higher judiciary.<br />

12<br />

COMBAT LAW SEPTEMBER-DECEMBER 2009

DALIT RIGHTS<br />

Over time it created a certain<br />

measure of confidence in Dalits that<br />

they have a protective cover and also<br />

produced a sense of wariness in the<br />

potential perpetrators of atrocities.<br />

However, the full thrust of the Act is<br />

not available on account of deficiencies<br />

in the Act and in various aspects<br />

of the implementation of the Act.<br />

As a result of the traditional<br />

Indian socio-economic structure still<br />

largely prevalent today, most of the<br />

SCs live typically in a situation<br />

where they are the major<br />

segment/majority of agricultural<br />

wage labourers but a minority of the<br />

population. Their numerical vulnerability<br />

is accentuated by the socio-psychology<br />

of the caste system precluding<br />

support for them from labourers<br />

of other castes whose affinity is<br />

unfortunately more towards the<br />

large landowners of their respective<br />

castes. Juxtaposition of a caste of<br />

agricultural labourers (SC) with a<br />

caste of land-based DUC or DMC or<br />

DMBC to which most of the large<br />

landowners belong, provides an<br />

explosive situation which can be<br />

ignited by any immediate spark.<br />

Dalits’ resistance to various forms of<br />

discrimination and demand for normal<br />

civilised inter-personal, intercommunity<br />

relations is opposed<br />

especially by major land-owning and<br />

land-controlling DUCs, DMCs and<br />

DMBCs.<br />

The upward mobility that a small<br />

proportion of SCs have achieved<br />

through education and reservation<br />

and consequent change in lifestyle is<br />

an eyesore to those who are accustomed<br />

to seeing SCs as only indigent<br />

and subservient labourers.<br />

Even legitimate protection of<br />

their rights when encroached upon<br />

by others (the instance of encroachment<br />

on Balmiki Ashram land in<br />

Gohana in Haryana by an adjacent<br />

lawyer of the dominant upper castes)<br />

is perceived as intolerable and insolent<br />

rebellion and is resentfully<br />

stored in the mind waiting for an<br />

opportunity to wreak collective<br />

“vengeance”.<br />

Evidential analysis of atrocities<br />

Atrocities out of demand for better wages<br />

● Kilavenmani holocaust in Tamil<br />

Nadu, 25.12.1968<br />

● Atrocity in Gurha Slathian, Jammu<br />

& Kashmir, 1985,<br />

● Bihar massacres at Belchi,<br />

27.05.1979<br />

● Pipra, 26-27.02.1980<br />

● Nonhi-Nagawa, 16-17.06.1988<br />

● Damuha-Khagri Toli, 11.08.1988<br />

Atrocities connected with bonded labour<br />

● Killing of Bacchdas in Mandsaur<br />

district, MP, 1982<br />

● Atrocity on bonded SC quarrying<br />

labourers at Chikkabasavanahalli,<br />

near Bangalore, Karnataka, 1976<br />

Atrocities connected with land<br />

● Atrocity in Rakh Amb Tali, Jammu<br />

& Kashmir, 10.07.1988<br />

● Killings etc., in Bihar at Bodh Gaya,<br />

08.08.1979<br />

● Chainpur, 10.12.1978<br />

● Khairlanji, Maharashtra,<br />

29.09.2006<br />

Atrocities connected with civic facilities<br />

● Killings & arson in Kachur, MP,<br />

25.06.1985<br />

● Atrocity in Diyalpur, Haryana<br />

26.11.1997<br />

● Hold-up of dead bodies of aged<br />

women, one each in Konalam, Tamil<br />

Nadu, 1982 and Patchalanadakuda,<br />

AP, 1989<br />

Atrocities graduating from untouchability<br />

● Jetalpur, Gujarat, 1980<br />

● Destruction/damaging of hundreds<br />

of huts/houses in many villages of<br />

south Arcot & adjoining districts,<br />

Tamil Nadu, September 1987 &<br />

January 1988<br />

● Massacre on account of an SC<br />

bridegroom riding on horseback at<br />

Kafalta, Uttar Pradesh, 09.05.1980<br />

● Masari, Rajasthan, 09.07.1989<br />

● Panwari, Uttar Pradesh, 02-06-1990<br />

● Kumher, Rajasthan, 06.06.1992<br />

● Drinking water segregation-related<br />

untouchability<br />

● School in Divrali, Rajasthan,<br />

December 1983<br />

● Kachur, Madhya Pradesh,<br />

25.06.1985<br />

● Udamgal-Khanapur, Karnataka,<br />

06.02.1988<br />

www.combatlaw.org 13

DALIT RIGHTS<br />

● Killings etc., on temple entry right<br />

issue at Hanota, MP, 1984, (rare case<br />

of death sentence for two on<br />

11.10.1988)<br />

● Nathdwara, Rajasthan, 1988 and<br />

again in 2004<br />

Atrocities connected with Dalit assertion<br />

of self-respect & equality<br />

● Eight Dalits were massacred, some<br />

of them well educated, in Tsunduru,<br />

Guntur District, Andhra Pradesh,<br />

06.08.1991.<br />

● Gohana, Sonepat District, Haryana<br />

where on August 31, 2005, 55 houses<br />

were destroyed by arson and another<br />

97 houses were looted. All of them<br />

were pucca houses. Twenty-five percent<br />

Balmikis of this town have,<br />

through their hard labour, savings<br />

and some education gave up the traditional<br />

occupation of scavenging<br />

and switched to more dignified occupations<br />

with some dignity.<br />

● The atrocities extending over eight<br />

to nine days from August 1, 1978 on<br />

Dalits in Marathwada following the<br />

resolution moved by the chief minister<br />

in the assembly for renaming the<br />

Marathwada University after Dr<br />

Babasaheb Ambedkar’s name in<br />

response to a long standing Dalit<br />

desire and in fulfillment of earlier<br />

promises. In the name of opposing<br />

the proposed renaming, on the one<br />

hand mobs attacked Dalit agricultural<br />

labourers with whom land-owning<br />

DUC had enmity on account of<br />

constant wage-disputes; on the other<br />

Majority of STs<br />

live in their own<br />

tribal territories or<br />

homelands where<br />

they are in majority<br />

and therefore are safe<br />

from physical attacks<br />

that SCs are<br />

vulnerable to. But<br />

when they are drawn<br />

out of their territories<br />

into the plains as<br />

migrant labourers<br />

etc., they become<br />

equally vulnerable<br />

as the SCs<br />

hand educated Dalits were targeted<br />

because of the improvement registered<br />

in their standard of life and<br />

education.<br />

Analysis of atrocities on STs<br />

A large majority of STs live in their<br />

own tribal territories or homelands<br />

where they are in majority and therefore<br />

are safe from physical attacks<br />

that SCs are vulnerable to. But when<br />

they are drawn out of their territories<br />

into the plains as migrant labourers<br />

etc., they become equally vulnerable<br />

as the SCs. One of the serious cases of<br />

atrocities on STs is the mass rape of<br />

six ST women labourers in Padaria,<br />

Bihar.<br />

In their homelands they are<br />

sometimes subjected to mass killing<br />

not at the hands of mobs but the<br />

police when they resist illegal acquisition<br />

of their lands or their other<br />

age-old traditional rights. On April<br />

19, 1985, in Banjhi area of Sahibganj<br />

district in Bihar, 15 STs including an<br />

ex-MP were killed in police firing on<br />

an agitated mob protesting against<br />

deprivation of traditional fishing<br />

rights by the government, which settled<br />

a tank in favour of a non-local,<br />

non-ST.<br />

The second incident was in<br />

Indravalli, Adilabad district of<br />

Andhra Pradesh in 1978 where 10<br />

STs were killed in police firing in<br />

connection with a land dispute.<br />

Killing in police action is not covered<br />

by the PoA and many more deficiencies<br />

in the PoA Act hamper its benefits<br />

reaching the Dalits promptly,<br />

effectively and fully and right to life<br />

under Article 21 has not been made a<br />

reality for them. The provision in section<br />

14 (2) requiring the state government<br />

to specify for each district a<br />

court of session to be a special court<br />

to try the offences under this Act is<br />

also not fully implemented. This contradicts<br />

the very purpose “of providing<br />

for speedy trial”, because trial<br />

will not be speeded up by merely<br />

calling an existing court (with all of<br />

its load of various cases) a special<br />

court. Instead the section ought to<br />

have provided and even now ought<br />

to provide for the establishment of an<br />

exclusive special court in each district<br />

exclusively to try the offences<br />

under this Act, on day-to-day basis<br />

and no other offences with corresponding<br />

provisions for an exclusive<br />

special public prosecutor and a special<br />

investigating officer.<br />

Section 3 in the Act does not list<br />

among the crimes of atrocities social<br />

boycott, economic boycott, social<br />

blackmail and economic blackmail,<br />

which are realities faced by Dalits<br />

whenever they make just demands<br />

or resist injustices or asserts their<br />

rights. Section 3 (2) of the Act does<br />

not provide death sentence for mur-<br />

14<br />

COMBAT LAW SEPTEMBER-DECEMBER 2009

DALIT RIGHTS<br />

der where the court considers death<br />

sentence appropriate.<br />

The protection of section 10 of the<br />

Act by externment is not available for<br />

the SCs who are the main victims of<br />

the atrocities (more than 80 percent<br />

of atrocities against SCs and STs are<br />

committed on SC) while the share of<br />

SCs specifically in cases of arson and<br />

grievous hurt is close to 90 percent.<br />

The Act also fails to take the SC<br />

converts to Christianity (SCX) or Dalit<br />

Christians within the protective<br />

umbrella of its ambit though SCX have<br />

been subjected to atrocities not because<br />

of their religion but because of the<br />

same reason why SC Hindus have<br />

been victimised. This was among the<br />

issues, which held up the commencement<br />

of the proper trial in the<br />

Tsunduru case till November 2004.<br />

Deficiencies in implementation<br />

This falls in addition to deficiencies<br />

in the Act itself. No matter how<br />

sound an Act is, unless the personnel<br />

at different levels in charge of its<br />

implementation perform totally in<br />

accordance with the letter and spirit<br />

of the Act, its implementation will<br />

fall short of the objective of reaching<br />

the protection of the Act to all the<br />

people intended. One of the practical<br />

problems experienced by the<br />

victims and survivors of atrocities<br />

and by Dalit and human rights<br />

activists at the field level is the<br />

indifference of local level personnel<br />

and callous attitude of higher<br />

authorities (all subject to honourable<br />

exceptions).<br />

Analysis of atrocities<br />

A close study of the annual reports<br />

laid in Parliament as required by section<br />

21 (4) of the PoA Act reveals that<br />

of the total number of cases with<br />

police at beginning of each year<br />

including those brought forward<br />

from previous year, only 50-60<br />

percent have been chargesheeted<br />

in courts.<br />

Table (1) shows the percentages<br />

of disposal of cases in courts.<br />

From the point of view of the victims<br />

of atrocities the figures in the<br />

4th row are the most relevant. While<br />

they may not be aware of statistical<br />

details, the victims’ perception is that<br />

the Act and its implementation fall<br />

far short of their expectation and<br />

need and the SCs in each area are<br />

aware of the acquittals in many serious<br />

cases of atrocities and consequent<br />

miscarriage of justice.<br />

The Dalits perceive this as a failure<br />

of the complete system and are<br />

not interested in the apportionment<br />

of blame among the different limbs<br />

of the system and of the State.<br />

The low figures in row 1 are also<br />

within their perception in the shape<br />

of the situation in which substantive<br />

trial in Tsunduru (06.08.1981) case<br />

could start only in November 2004<br />

and the Kumher (06.06.1992) case is<br />

still languishing.<br />

All in all, though the Act has<br />

given some sense of security to the<br />

Dalits, its effectiveness has not measured<br />

up to its potential and purpose<br />

on account of deficiencies in the Act<br />

1 Percentage of cases<br />

in which trial<br />

completed in courts<br />

at beginning of the<br />

year including B/F of<br />

previous year<br />

2 Percentage of cases<br />

convicted to trialcompleted<br />

cases<br />

3 Percentage of cases<br />

acquitted or<br />

discharged to trial<br />

completed cases<br />

4 Percentage of cases<br />

convicted to total<br />

cases in courts<br />

5 Percentage of cases<br />

acquitted or<br />

discharged to total<br />

cases in courts<br />

Year 2003<br />

(Latest<br />

Annual<br />

Report<br />

tabled on<br />

25.11. &<br />

28.11.2005)<br />

and delay and laches in investigations<br />

and the slow progress of trial<br />

and large scale acquittals.<br />

Further, the annual reports laid<br />

before Parliament do not bear the<br />

impress of in depth and critical analysis,<br />

identification of problems and<br />

Table-1<br />

efforts at resolution. They look like a<br />

mere enumerative and uncritical<br />

recital of state governments’ reports.<br />

For e.g., there is nothing to explain<br />

the sudden and steep and primafacie<br />

inexplicable and incredible fall<br />

of new cases registered in Uttar<br />

Pradesh from 9,764 in 2001 to 5,841 in<br />

2002 and 1,778 in 2003!<br />

The greatest defect is that special<br />

mobile courts do not exist in every<br />

district as a means of handing out<br />

swift and deterrent punishment on<br />

the spot. Wherever a mobile court<br />

exists and has delivered punishment<br />

immediately, I have personally seen<br />

the impact of fear and curbing of<br />

untouchability practice at least for<br />

some time (doses need to be repeated<br />

periodically for this chronic disease).<br />

2002 2001 2000 1999<br />

14 % 21 % 11 % 8 % 10 %<br />

13 % 11 % 12 % 11 % 12 %<br />

88 % 89 % 88 % 89 % 88 %<br />

2 % 2 % 1 % 1 % 1 %<br />

12 % 18 % 9 % 6 % 8 %<br />

Where special mobile courts exist<br />

their functioning is often hampered<br />

by thoughtless actions like withdrawal<br />

of vehicles, rendering mobile<br />

courts immobile on certain occasions,<br />

keeping vacant posts unfilled etc.<br />

This has laid the foundation for non-<br />

www.combatlaw.org 15

DALIT RIGHTS<br />

and-ineffective implementation of<br />

the categorical constitutional mandates<br />

of Article 17 read with Article<br />

14 and 46.<br />

Some neo-modern<br />

forms of untouchability<br />

have appeared in rural<br />

as well as urban areas<br />

in many parts of the<br />

country, in keeping with<br />

new developments.<br />

For example, explicit<br />

caste bias at village<br />

teashops is a recent<br />

phenomenon which has<br />

paved way for a variety<br />

of discriminatory<br />

practices such as<br />

separate seating,<br />

separate and usually<br />

old, dirty and cracked<br />

or chipped glasses,<br />

for SCs<br />

Deficiencies in implementation<br />

The deficiencies in the Act have been<br />

compounded by severe deficits of<br />

implementation all along the line,<br />

presenting a more dismal picture<br />

than even the implementation of the<br />

POA Act.<br />

Following are the highlights of a<br />

statistical analysis of the annual<br />

reports tabled in each house of<br />

Parliament by the government from<br />

1977 up to 2003:<br />

● Of the total number of cases with<br />

police at beginning of each year<br />

including those brought forward<br />

from previous year, only 1/8th to<br />

1/5th have been chargesheeted in<br />

courts.<br />

● A number of states are reporting nil<br />

against new cases registered in the<br />

year, which is far from reality.<br />

● The number of cases reported by<br />

many states is unrealistically low, for<br />

example, only two in 2002 and three<br />

in 2003 in Tamil Nadu.<br />

● The percentage of conviction in<br />

courts and other quantitative data<br />

are much more bleak than even for<br />

the PoA Act both at the police stage<br />

as well as at the court stage.<br />

● The figures do not mesh with the<br />

ground level reality of rampant<br />

untouchability and the registration<br />

and variations is apparently the<br />

product of casualness and in some<br />

cases perhaps even election-related<br />

remote controls.<br />

Even the pan-India picture<br />

belongs to a different world away<br />

from reality.<br />

The annual reports do not contain<br />

any indication either of the state governments<br />

or the central government<br />

making efforts to fulfill the specific<br />