You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

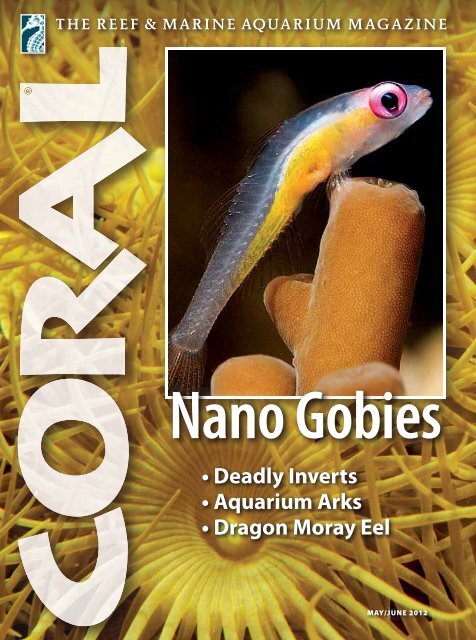

THE REEF & MARINE AQUARIUM MAGAZINE<br />

<strong>Nano</strong> <strong>Gobies</strong><br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

MAY/JUNE 2012

RadionTM<br />

LED LIGHTING<br />

Sleek. Sophisticated. High-tech. Beautiful.<br />

The new Radion Lighting features 34 energy-efficient LEDs<br />

with five color families. Improved growth. Wider coverage.<br />

Better energy efficiency. Customizable spectral output.<br />

In short, a healthier, more beautiful ecosystem.<br />

EcoTech Marine. Revolutionizing the way people think<br />

about aquarium technology.<br />

®

EDITOR & PUBLISHER | James M. Lawrence<br />

INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHER | Matthias Schmidt<br />

INTERNATIONAL EDITOR | Daniel Knop<br />

SENIOR ADVISORY BOARD |<br />

Dr. Gerald R. Allen, Christopher Brightwell,<br />

Dr. Andrew W. Bruckner, Dr. Bruce Carlson,<br />

J. Charles Delbeek, Dr. Sylvia Earle, Svein<br />

A. Fosså, Jay Hemdal, Sanjay Joshi, Larry<br />

Jackson, Martin A. Moe, Jr., Dr. John E.<br />

Randall, Julian Sprung, Dr. Rob Toonen,<br />

Jeffrey A. Turner, Joseph Yaiullo<br />

SENIOR EDITORS |<br />

Scott W. Michael, Dr. Ronald L. Shimek,<br />

<br />

Matt Pedersen<br />

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS |<br />

J. Charles Delbeek, Robert M. Fenner, Ed<br />

<br />

Mary Sweeney, John H. Tullock, Tim Wijgerde<br />

PHOTOGRAPHERS |<br />

<br />

Matthew L. Wittenrich, Vince Suh<br />

TRANSLATOR | Mary Bailey<br />

ART DIRECTOR | Linda Provost<br />

PRODUCTION MANAGER | Anne Linton Elston<br />

ASSOCIATE EDITORS |<br />

Louise Watson, Alexander Bunten,<br />

Bayley R. Lawrence<br />

EDITORIAL & BUSINESS OFFICES<br />

Reef to Rainforest Media, LLC<br />

140 Webster Road | PO Box 490<br />

Shelburne, VT 05482<br />

Tel: 802.985.9977 | Fax: 802.497.0768<br />

CUSTOMER SERVICE 570.567.0424<br />

ADVERTISING SALES |<br />

James Lawrence | 802.985.9977 Ext. 7<br />

james.lawrence@coralmagazine-us.com<br />

BUSINESS OFFICE |<br />

<br />

NEWSSTAND | Howard White & Associates<br />

PRINTING | <br />

CORAL ® , The Reef & Marine Aquarium Magazine,<br />

(ISSN:1556-5769) is published bimonthly in January,<br />

March, May, July, September, and November by Reef<br />

to Rainforest Media, LLC, 140 Webster Road, PO Box<br />

490, Shelburne, VT 05482. Periodicals postage paid<br />

at Shelburne, VT, and at additional entry offices.<br />

Subscription rates: U.S., $37 for one year. Canada, $49 for<br />

one year. Outside U.S. and Canada, $57 for one year.<br />

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to CORAL,<br />

PO Box 361, Williamsport, PA 17703-0361.<br />

CORAL ® is a licensed edition of KORALLE Germany,<br />

ISSN:1556-5769<br />

Natur und Tier Verlag GmbH | Muenster, Germany<br />

All rights reserved. Reproduction of any material from this<br />

issue in whole or in part is strictly prohibited.<br />

COVER:<br />

Redeye Goby (Bryaninops natans),<br />

photo by Inken Krause.<br />

BACKGROUND:<br />

Zooantids<br />

(unidentified), photo by<br />

Daniel Knop.<br />

4<br />

LETTER FROM EUROPE by Daniel Knop<br />

7 EDITOR’S PAGE by James M. Lawrence<br />

8 LETTERS<br />

10 REEF NEWS<br />

22 RARITIES by Scott W. Michael<br />

The Dragon Moray (Enchelycore pardalis)<br />

34 VIEWPOINT: THE AQUARIUM ARK by Matt Pedersen<br />

FEATURE ARTICLES<br />

48 PYGMY GOBIES<br />

by Daniel Knop<br />

56 PYGMY GOBIES: DIVERSITY AND AQUARIUM HUSBANDRY<br />

by Inken Krause<br />

70 OVERVIEW: PYGMY GOBIES IN THE SEA AND THE AQUARIUM<br />

by Inken Krause<br />

72 THE ELDERS<br />

How long can a coral live?<br />

by Ronald L. Shimek, Ph.D.<br />

86 LONG ISLAND GOLD RUSH<br />

by Todd Gardner<br />

94 CUBA’S UNDERWATER PARADISE:<br />

LOS JARDINES DE LA REINA<br />

Part 1: Picturebook Caribbean reefs by Werner Fiedler<br />

100 SUCCESSFUL BREEDING OF THE<br />

YELLOW-BANDED PIPEFISH (Doryrhamphus pessuliferus)<br />

by Inken Krause<br />

AQUARIUM PORTRAIT<br />

105 AN ENERGY-SAVING SWISS AQUARIUM<br />

Created by Rueda Furter and Brigitte Utz<br />

by Inken Krause<br />

DEPARTMENTS<br />

115 SPECIES SPOTLIGHT:<br />

The Ambon Scorpionfish by Daniel Knop<br />

121 REEFKEEPING 101:<br />

Marine substrates by Daniel Knop<br />

126 CORALEXICON: Technical terms that appear in this issue<br />

128 RETAIL SOURCES: Outstanding aquarium shops<br />

130 ADVANCED AQUATICS:<br />

Behind the scenes: mammoth reef, mammoth challenges<br />

by J. Charles Delbeek<br />

134 ADVERTISER INDEX<br />

136 REEF LIFE: by Denise Nielsen Tackett and Larry P. Tackett<br />

www.CoralMagazine-US .com

LETTER<br />

Inotes from DANIEL KNOP<br />

s bigger really better and more interesting?<br />

Not necessarily—tiny can<br />

often win hands down! And that applies<br />

not only to gobies, not even just<br />

to aquarium occupants in general,<br />

but also to the aquariums in which<br />

we keep these dwarfs. Sometimes less<br />

really is more.<br />

Granted, you have to look very closely<br />

to appreciate dwarf gobies, but on the<br />

other hand, you notice more when you<br />

look closely. A coral fish doesn’t have<br />

to be big to be fascinating and striking.<br />

It’s true that it is difficult to miss a large<br />

lemon yellow or royal blue surgeonfish<br />

swimming around the aquarium, but a<br />

pair of Gobiodon gobies 1.2 inches (30<br />

mm) long, resting immobile on their bellies among the<br />

branches of a stony coral—that’s something else again.<br />

Happy reading!<br />

Their size is undoubtedly part of their<br />

survival strategy—the smaller you are<br />

the more difficult it is for predators to<br />

see you. But from the aquarist’s point<br />

of view, it is all too easy for dwarf gobies<br />

to come to grief in an aquarium<br />

of normal size.<br />

It is much better to keep these tiny<br />

fishes in a small tank, where there<br />

is less to distract us from them and<br />

we are more focused. In a large reef<br />

aquarium a pair of 0.75-inch (20-<br />

mm) Bryaninops gobies are no more<br />

than a minor detail, but in a nano<br />

tank they are the main attraction, and<br />

their true charm becomes apparent.<br />

FOCUS: BREATHER<br />

This picture of a young clownfish, nestling safe from<br />

attack among the sheltering tentacles of its host<br />

anemone, conveys an impression of security. But the<br />

sense of peace is deceptive, as the little fish is quite<br />

out of breath, gasping for air—or should I say water?<br />

For several days it has been engaged<br />

in strenuous “virtual” battles that last<br />

for hours.<br />

This fish lived in a sales tank in an<br />

aquarium store, and the neighboring<br />

tank was home to a belligerent Maroon<br />

Clownfish (Premnas biaculeatus),<br />

about the same size, that repeatedly<br />

sallied forth from its host anemone,<br />

seeking to provoke a fight. Only a few<br />

seconds before this photo was taken,<br />

the two had finally become exhausted<br />

after confronting each other violently all day through<br />

the glass, with only short intervals of peace.<br />

This Twoband Anemonefish now lives in a reef<br />

aquarium, where it has a partner and a new host<br />

anemone.<br />

—Daniel Knop<br />

A small Twoband Anemonefish<br />

(Amphiprion bicinctus) nestling among<br />

the tentacles of its host Long Tentacle<br />

Anemone (Macrodactyla doreensis).<br />

4 CORAL

CORAL<br />

5

©2011 AQUATIC LIFE LLC<br />

HEAR THE VOCAL STYLINGS<br />

OF KING NEPTUNE.<br />

1-800-286-2326<br />

As part of an ongoing effort to bring the ocean to you, we bring you the Conch Line.<br />

24/7 phone access to all the sounds of the sea. Wherever you are. For free. Enjoy.<br />

BRINGING THE OCEAN TO YOU, WHEREVER YOU MAY BE.<br />

aquaticlife.com

getting a species out of the endangered zone<br />

For a fish that was supposed to be the marine equivalent<br />

of the guppy, the Banggai Cardinalfish has proved<br />

itself to be an enigma. We were fortunate<br />

enough to obtain one of the first pairs of Pterapogon<br />

kauderni imported following the species’ introduction<br />

to the aquarium world by Dr. Gerry Allen at MACNA<br />

VII in Louisville in 1995. Placed in a small desktop<br />

aquarium for observation, they spawned within a month<br />

and the male went on a food fast, brooding a mouthful<br />

of eggs. There were but 17 fry—tiny, perfect replicas of<br />

their parents on the day they emerged—but they did not<br />

hesitate to attack and eat frozen Artemia nauplii.<br />

We assumed that home breeders would embrace the<br />

species, then selling for princely sums, and that every local<br />

fish store would soon have local suppliers of captivebred<br />

Banggai Cardinalfishes.<br />

Seventeen years later, nothing of the sort has come to<br />

pass, and in 2007 Pterapogon kauderni was placed on the<br />

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)<br />

Red List of endangered species. With the 2011 publication<br />

of The Banggai Cardinalfish: Natural History, Conservation,<br />

and Culture of Pterapogon kauderni (Wiley,<br />

2011), Dr. Alejandro Vagelli squarely blamed the marine<br />

aquarium trade, amateur aquarists, and the “aquarium<br />

media” for dramatically reducing wild populations of the<br />

fish, even completely wiping it out in some locations.<br />

After reading his damning words and the dismaying<br />

Red List reports, we made a personal resolution to respond.<br />

Dr. Vagelli’s work has been questioned by some,<br />

but we learned from wildlife conservation sources working<br />

in the Banggai Islands that there are, indeed, problems<br />

in the aquarium fishery there that need addressing.<br />

Dr. Allen himself did some the field work that led to the<br />

species’ endangered listing, and he believes that corrective<br />

actions are warranted.<br />

It turns out that others were ready to act as well. The<br />

Rising Tide Conservation Initiative, led by Dr. Judy St.<br />

Leger and in concert with the Association of Zoos and<br />

Aquariums, is targeting P. kauderni as one of five popular<br />

aquarium species that need to be aquacultured commercially<br />

to take the pressure off wild populations.<br />

A group of marine biologists and fisheries scientists<br />

at the University of Florida’s Tropical Aquaculture Lab<br />

(TAL) at Ruskin have already started to turn the Rising<br />

Tide goals into realities. Under the direction of aquaculturist<br />

Craig Watson, M.Aq., who is the director of the<br />

lab, Matthew Wittenrich, Ph.D., had been looking into<br />

the challenges of Banggai Cardinalfish culture.<br />

His colleague, fish veterinarian Dr. Roy Yanong, had<br />

been researching the puzzling mass deaths of so many<br />

wild-caught Banggais being brought into the U.S. His lab<br />

found an iridovirus in samples of dead fish from a group<br />

of 1,000 broodstock specimens bought by a U.S. commercial<br />

aquaculture operation. All 1,000 had died of the<br />

disease.<br />

When looking for assistance in funding a TAL research<br />

expedition to the Banggai Islands, Drs. Wittenrich<br />

and Yanong contacted this magazine. We immediately<br />

said yes, not quite sure where this small company,<br />

still in its launch phase and experiencing everyday growing<br />

pains, would find the money. We decided to embed<br />

journalist and CORAL senior editor Ret Talbot in the<br />

expedition and to invite Matt Pedersen, senior editor<br />

and an accomplished home-scale breeder, to work on a<br />

new guide for a species that had proved uncooperative<br />

for many would-be hobbyist breeders. Plans were quickly<br />

made to produce a series of magazine articles and a definitive<br />

book. But how to fund all of this?<br />

Enter Kickstarter, a radical new “crowd-funding”<br />

tool for creative projects in need of unconventional support.<br />

Thanks largely to the generous and enthusiastic<br />

support of CORAL readers, advertisers, and supporters,<br />

we have just succeeded in exceeding our funding goals<br />

after a month of seeking backers for the project.<br />

All of us involved in this believe there is no single solution<br />

to the problems that have beset the Banggai Cardinalfish.<br />

Our goals are to help foster a healthier, more<br />

sustainable fishery for wild specimens, to find protocols<br />

for commercial-scale mariculture and aquaculture, to<br />

establish better methods for hobbyists wishing to breed<br />

this species to meet local demands, and to publish the<br />

whole story and all of the lessons learned in CORAL and<br />

in the Banggai project book. In this, we value the interest,<br />

suggestions, criticisms, and involvement of the entire<br />

CORAL community.<br />

James Lawrence<br />

www.banggai-rescue.com<br />

CORAL<br />

7

correspondence from our readers<br />

THE THREAT OF TANKED<br />

I think that Mr. Mark Grabow, in his answer to my letter<br />

about [the TV show] Tanked, is indeed missing the whole<br />

point. (January/February CORAL Letters.)<br />

The more we learn about the animals we keep, the<br />

more we know that an aquarium is much more than<br />

simple “laboratory” equipment in which we just need to<br />

keep proper salinity, oxygen, pH, nitrogen, and phosphorus.<br />

No matter how pristine your tank chemistry, stress<br />

will be a serious issue unless the<br />

environment has the required<br />

“complexity” of the animals’ natural<br />

habitats. And stress will lead<br />

to disease and early death.<br />

Moreover, those disgusting<br />

posh fishbowls offer no educational<br />

value at all. It is completely<br />

impossible to observe anything<br />

resembling the natural behavior<br />

of a fish inside those phone<br />

booths and gimmick-filled boxes.<br />

Which of course leads to the attacks<br />

to which aquarium keeping<br />

is being subject right now.<br />

Aquarium keeping can be<br />

done in an ethical way. Aquarium<br />

keeping can have an outstanding<br />

educational value. But of course<br />

I am speaking about aquariums,<br />

not bizarre fish bowls. Tanked is<br />

a real threat, maybe one of the<br />

worst, to the credibility of aquarium keepers and the<br />

whole aquarium industry.<br />

Borje Markos<br />

Algorta, Vizcaya, Spain<br />

ZEN & THE ART OF AQUARIUMS<br />

My husband and I were excited to hear of the Animal<br />

Planet show Tanked from a non-aquarist neighbor, but<br />

were very disappointed once we actually saw it. Tanked<br />

more closely resembled a slap-dash DIY home remodeling<br />

segment than an educational and environmentally<br />

responsible introduction to the hobby we love.<br />

We wondered what sort of hefty service contracts the<br />

obviously wealthy clients of Tanked had agreed to pay for.<br />

Obviously they knew nothing about their new equipment<br />

or the new creatures in their care. Would they be<br />

willing to take care of it all, or would they would simply<br />

throw money at their cool new piece of “aquarium furniture”<br />

by paying someone else to deal with the upkeep?<br />

We decided they’d definitely pay.<br />

While I was watching the first episode, the book Zen<br />

and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance came to mind. The<br />

book explains that having a motorcycle requires a steady<br />

commitment to continually educate yourself in order to<br />

understand the complex details of its essence. Gaining<br />

understanding is part of the joy of ownership, and only<br />

comes from time spent in handson<br />

experience. We think having<br />

a marine aquarium brings the<br />

same responsibilities to its owner.<br />

It would be interesting to see<br />

some expert, one-on-one maintenance<br />

mentoring in Tanked, but<br />

instead, we get the “wow factor”<br />

of flashy set-ups and super-fast<br />

installations. This show, now<br />

starting a second season, was<br />

produced for our debatable entertainment<br />

pleasure, not to promote<br />

the love of nature or good<br />

husbandry.<br />

If Animal Planet had simply<br />

stuck to what has made other<br />

nature shows great (The Undersea<br />

World of Jacques Cousteau, Wild<br />

Kingdom, Nova), the result would<br />

have been of much better quality<br />

and much more interesting.<br />

We are in complete agreement with the sentiments<br />

expressed by reader Borje Markos and feel that Tanked<br />

casts us all in a very unfavorable light.<br />

Dianne Krogh<br />

Oak Harbor, Washington<br />

MARINE BREEDERS INVITATION<br />

Kudos to CORAL for the excellent cover stories on breeding<br />

successes in the March/April issue. Serious and<br />

would-be breeders are invited to attend the 3rd Annual<br />

Marine Breeders Initiative Workshop on July 28 at the<br />

Cranbrook Institute of Science in Bloomfield Hills, MI.<br />

Tal Sweet<br />

www.mbiworkshop.com<br />

Readers are invited to write the Editor:<br />

Editors@CoralMagazine-US.com<br />

8 CORAL

Purchasing Marine Animals Will Never Be The Same.<br />

Every fish has a Story.<br />

shed some light on yours.<br />

Look for QM labels on tanks at your LFS<br />

Scan this QR code to get the lowdown on a fish<br />

before you buy! What it is, what it eats, if it’s<br />

social, even where it came from and when it<br />

was shipped! Available at Quality Retailers.<br />

Look for the<br />

New QM Label<br />

Visit www.qualitymarine.com for more information

NEWS<br />

findings and happenings of note in the marine world<br />

Remembering Bill Addison:<br />

“Fishes would see him and spawn”<br />

It was on the evening of February 17th that we received<br />

word from long-time fish breeder and friend Joe Lichtenbert.<br />

“Some very sad news,” wrote Lichtenbert. “Bill passed<br />

away in his sleep last night…. Although Bill suffered<br />

from diabetes requiring daily injections, pretty bad arthritis,<br />

and macular degeneration, he never complained.<br />

His famous words of wisdom were ‘So be it!’<br />

“Bill was a WWII vet. His personal exploits would<br />

make you proud to be an American. The family is not<br />

planning any of the normal services. Instead, he will be<br />

cremated and his ashes will be spread across the mountain<br />

passes in his home state of Wyoming that he so<br />

loved. I, and the world, have lost a great and inspirational<br />

man.”<br />

William Middleton Addison’s obituary was published<br />

on February 22 in the Platte County Record-Times<br />

and gives us insights beyond the man who was known in<br />

the aquarium world as Bill Addison, pioneering marine<br />

fish breeder and founder of C-Quest Hatchery.<br />

In his 85 years of life, Addison accomplished and<br />

saw more than most, and as Matthew L. Wittenrich retells<br />

it,“He dug his first uranium mine by hand, amassed<br />

a collection of antique cars, and set up a tropical fruit<br />

plantation in Central America and a fish hatchery in<br />

Puerto Rico.”<br />

Indeed, Addision served in World War II as a Marine,<br />

returning afterward to graduate from high school<br />

and attend college. He married his wife, Arline, in 1952.<br />

Addison mined uranium and, later, white marble in<br />

Wyoming. Ultimately, Addison sold the mining business<br />

to pursue his other interests, including the C-Quest<br />

Marine breeding<br />

pioneer Bill Addison<br />

at his C-Quest<br />

hatchery.<br />

M.L. WITTENRICH<br />

10 CORAL

Hatchery in Puerto Rico, which was moved to Wyoming<br />

in 2010, as reported on Reefbuilders.com in August 2010.<br />

C-Quest, founded in 1988, is the oldest operating<br />

marine ornamental fish hatchery in the country. In<br />

1997, Joyce Wilkerson wrote an extensive piece about the<br />

C-Quest facility in Puerto Rico. The author of Clownfishes<br />

(Microcosm, 1998), Wilkerson worked with Bill<br />

Addison for a number of years before her death in 2007.<br />

It is interesting to note Wilkerson’s concern over the<br />

loss of several hatcheries in the late 1990s, leaving only<br />

C-Quest and Joe Lichtenbert’s Reef Propagations, Inc.<br />

producing captive-bred marine fish for the aquarium industry.<br />

These businesses fought an uphill battle for profitability<br />

that seems to rage on today.<br />

When Lichtenbert retired in 2010, only C-Quest was<br />

left standing from that early era. C-Quest, now under<br />

the leadership of Addison’s daughter, Katy, continues to<br />

operate, continually extending the longevity record for a<br />

commercial marine ornamental hatchery.<br />

—Matt Pedersen & the staff of CORAL<br />

Keep your eyes open at the fish market!<br />

If you want to discover a new fish species, you don’t necessarily<br />

have to go diving in the depths of the ocean.<br />

Sometimes it is enough to take a look at the offerings of<br />

a fish market, as species unknown to science have been<br />

found there astonishingly frequently. However, to spot<br />

such fishes you need not only an extensive knowledge<br />

of the fish groups in question but a well-trained eye for<br />

detail.<br />

For example, a group of taxonomists were recently<br />

wandering around at the Tashi Fish Market in northeastern<br />

Taiwan. They were primarily looking for freshly<br />

landed sharks to compare with preserved material caught<br />

decades previously, in order to check for changes that<br />

had occurred. But what they actually discovered was a<br />

basket containing sharks of the order Squaliformes that<br />

even they, as experts, couldn’t identify. Male and female<br />

specimens were taken back to the research laboratory<br />

and examined in detail. The scientists established that<br />

the fishes were strikingly different from the new species<br />

previously known. This ultimately led to the scientific<br />

description of the species as Squalus formosus, with the<br />

species epithet formosus referring to the former name<br />

of Taiwan: Ilha Formosa, which is the Portuguese for<br />

“beautiful island.”<br />

That this was no isolated case is illustrated by the famous<br />

discovery made by the South African lay biologist<br />

Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer. On December 23, 1938,<br />

she found an unusual fish, 59 inches (150 cm) long, in a<br />

large catch of fishes. She immediately realized that it had<br />

to be a species that science had previously regarded as extinct:<br />

the coelacanth. This is an ancient fish with fleshy<br />

Nadelkopf?<br />

The influence of German on reef aquarium<br />

keeping is evident in the use of words like<br />

“Kalkwasser.” But something gets lost in<br />

the translation when you talk about a pin<br />

cap in German. Like “pinhead” in English,<br />

“nadelkopf” is slang for “stupid person.”<br />

A pin cap on a glue dispensing bottle is<br />

not a stupid idea. On the contrary, it’s one<br />

of those handy Little details that’s pretty<br />

clever. Next time you need a big quantity<br />

of adhesive for your aquascaping and<br />

coral fragging activities, just reach for our<br />

CorAffixPro, ten ounces of fast-curing,<br />

easy to use, ultra pure cyanoacrylate gel<br />

with a 2 year shelf life, and a pin cap<br />

to keep the tip from clogging.<br />

Need something big?<br />

Think Little.<br />

www.twolittlefishies.com<br />

12 CORAL

Keep your eyes open at the fish<br />

market, as species unknown to science<br />

can turn up there.<br />

D. KNOP<br />

fins that it can use alternately<br />

when swimming, which may have<br />

facilitated its descendants moving<br />

onto land. For this reason is<br />

has been surmised that this fish<br />

and terrestrial vertebrates share a<br />

common ancestor that represents<br />

the transition from aquatic to terrestrial<br />

vertebrates. As head of the<br />

Museum of Marine Biology in the<br />

South African town of East London,<br />

Courtenay-Latimer was able<br />

to select interesting specimens<br />

for her museum from every major<br />

catch made locally, even before it was offered for sale in<br />

the fish market. She attempted to preserve this rare specimen<br />

as a matter of urgency by wrapping it in formalinsoaked<br />

cloths, and she made a drawing of it. When it was<br />

subsequently scientifically described, the genus newly<br />

erected for the fish, Latimeria, was named in her honor<br />

and the species after the place where it was discovered<br />

(chalumnae). It wasn’t until 1987 that the German biologist<br />

and animal photographer Professor Hans Fricke discovered<br />

the natural habitat of the coelacanth.<br />

In 1997 and 1998 the German biologist Dr. Mark<br />

Erdmann and his wife, still students at the time, created<br />

a further sensation by discovering dead coelacanths<br />

at a fish market in Manado at the northernmost tip of<br />

Sulawesi (Indonesia), around 6,200 miles (10,000 km)<br />

from the spot where Latimeria chalumnae was originally<br />

discovered. Professor Fricke began a new underwater<br />

search there and eventually tracked down this second<br />

CORAL<br />

13

The coelacanth Latimeria chalumnae—this is<br />

a plastic model—was discovered by Marjorie<br />

Courtenay-Latimer at a fish market.<br />

Latimeria species, the Manado Coelacanth<br />

(Latimeria menadoensis), in its<br />

natural habitat. So far more than 500 live<br />

coelacanths have been found and many<br />

of them have been intensively observed<br />

and studied. So, keep your eyes open at<br />

the fish market!<br />

—Daniel Knop<br />

REFERENCES:<br />

White, W.T. and S.P. Iglesias. 2011. Squalus<br />

formosus, a new species of spurdog shark<br />

(Squaliformes: Squalidae) from the western<br />

North Pacific Ocean. J Fish Biol, doi:10.1111/j.<br />

1095-8649.2011.03068.x<br />

Acidification<br />

of the Mediterranean<br />

The world’s seas absorb around a quarter<br />

of the carbon dioxide (CO 2 ) emissions<br />

that result from the use of fossil<br />

fuels and deforestation. That represents<br />

around a million tons of carbon dioxide<br />

per hour. This leads to changes in the<br />

chemical composition of the seas, in particular<br />

an increase in acidity. The increase<br />

poses a threat to the organisms that form<br />

skeletons or shells of calcium carbonate—corals<br />

and mollusks, for example.<br />

Jean-Pierre Gattuso of the Laboratory for<br />

Oceanography in Villefranche-sur-mer<br />

(CNRS/UPMC) and his colleagues have<br />

conducted an international study on this<br />

theme. The results have been published in<br />

the journal Nature Climate Change.<br />

The researchers chose corals, crustaceans,<br />

and mollusks from around the<br />

island of Ischia (Gulf of Naples, Italy),<br />

as the water there is already excessively<br />

acidified by natural sources of CO 2 as a<br />

D. KNOP<br />

14 CORAL

The warming of the seas is not the only cause of the demise of numerous calcium<br />

carbonate–forming organisms. Decreasing pH is an additional factor.<br />

Calcium carbonate–forming organisms such as<br />

corals and mollusks (this is the Green Chiton,<br />

Chiton olivaceus) are reaching their limits of<br />

tolerance with regard to ocean warming. The<br />

concomitant decrease in pH often results in<br />

mass die-offs.<br />

D. KNOP<br />

result of the volcanic activity of Mount<br />

Vesuvius. Using radioactive isotopes, they<br />

were able to show that calcium carbonate<br />

production by these organisms is possible<br />

even at the acidity level expected for the<br />

year 2100 (pH 7.8, compared to a current<br />

pH of 8.1). The tissue and the organic<br />

layers that coat the skeletons and shells<br />

of these organisms play an important<br />

role in protecting their calcium carbonate<br />

structures. The parts that aren’t protected<br />

by tissue or organic molecules are<br />

more vulnerable and dissolve rapidly, depending<br />

on the acidity of the water. The<br />

researchers demonstrated that resistance<br />

is significantly reduced the longer these<br />

organisms are exposed to unusually high<br />

temperatures (83.3°F [28.5°C]). Thus<br />

their mortality rate rises in line with the<br />

acidity.<br />

Some marine invertebrates are already<br />

living at temperatures close to their<br />

limits of tolerance, and this periodically<br />

leads to mass die-offs. The combination<br />

For local retailer, contact (800) 357-2995<br />

or go to www.cprusa.com<br />

CORAL<br />

15

of the warming of the Mediterranean and the acidification<br />

of its water will lead to a further increase in this<br />

phenomenon.<br />

—IDW/Marie de Chalup<br />

REFERENCES<br />

Rodolfo-Metalpa, R. et al. 2011. Coral and mollusc resistance to<br />

ocean acidification adversely affected by warming. Nature Clim<br />

Change 1: 308–312.<br />

300 little giant octopuses<br />

The sight of the 300 recently hatched larvae of the Giant<br />

Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) in the Vancouver<br />

Aquarium Marine Science Center engenders<br />

mixed feelings. The reproduction of<br />

animals in captivity is usually a reason<br />

for celebration, but this case is different<br />

for two reasons. First, these mollusks are<br />

relatively short-lived (their natural life<br />

span is only three to five years), and they<br />

typically die after breeding. The male dies<br />

shortly after mating with the female, and<br />

she survives only till the young hatch at<br />

the end of the punishing brooding phase,<br />

during which she takes no food. That is<br />

what happened to Vancouver’s male, and<br />

the female was expected to die as soon as<br />

her young had hatched.<br />

The second reason is<br />

that it is really difficult<br />

to rear the larvae of this<br />

species. It has proved possible<br />

to get them past the<br />

planktonic stage on one<br />

or two occasions, but this<br />

phase lasts an extremely<br />

long time (7–10 months),<br />

and losses are enormous during this period,<br />

even with optimal maintenance. Of<br />

course, the staff at the aquarium will do<br />

everything in their power to rear at least a<br />

few of the larvae, if only to broaden their<br />

knowledge of breeding cephalopods. They<br />

are all prepared for some exciting months<br />

of very hard work and happy to take up<br />

the challenge, but their expectation of<br />

success is not very high.<br />

Enteroctopus dofleini lives in the cool<br />

waters of the northern Pacific between<br />

California and Japan. It is the largest of<br />

all the octopuses; its body attains around<br />

24 inches (60 cm) in diameter and the<br />

arms about 80 inches (200 cm) in length,<br />

although the literature is full of gross exaggerations<br />

regarding length and body<br />

mass, such as an overall span of 30 feet<br />

(9 m) or a weight of up to 660 pounds<br />

(300 kg). As a rule they attain around<br />

100 pounds (45 kg), although they can<br />

get up to 165 pounds (75 kg). The largest<br />

specimens weighed supposedly tipped the<br />

scales at 300 and 401 pounds (136 and<br />

182 kg).<br />

In summer the adults migrate to<br />

deeper water to mate; in autumn the females<br />

return to shallow water to produce<br />

their clutches, which typically consist of<br />

20,000–70,000 eggs, sometimes up to<br />

100,000. The female guards her eggs con-<br />

16 CORAL

Enteroctopus dofleini is the<br />

largest species of octopus<br />

known, shown here in the<br />

aquarium with chilled water.<br />

The tentacles of<br />

Enteroctopus dofleini.<br />

D. KNOP<br />

tinuously until they hatch and, as mentioned earlier, takes no food during<br />

this period. Her genetic programming dictates the approaching end of her<br />

life, so it would be counter-productive to leave the eggs in order to go hunting<br />

and feed. The number of larvae that hatch appears to be significantly higher<br />

when the female octopus sacrifices herself to guard her clutch permanently<br />

than is the case when the eggs are incubated separately.<br />

—Daniel Knop<br />

REFERENCES<br />

Norman, M. 2000. Tintenfisch-Führer—Kraken, Argonauten, Sepien, Kalmare, Nautiliden.<br />

Jahr Verlag, Hamburg, Germany.<br />

CORAL<br />

17

Parenting comes at a price for male<br />

cardinalfish<br />

Being a great father can mean starving to protect the<br />

kids, putting up with a jealous spouse and, often, dying<br />

young—at least, if you are a marine cardinalfish.<br />

A survival strategy that has been a triumphant success<br />

for cardinalfishes for going on 50 million years<br />

could come unstuck due to rapid global warming, say<br />

scientists from the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral<br />

Reef Studies and James Cook University.<br />

“We studied how cardinalfishes have evolved over<br />

millions of years and found that these mouthbrooders<br />

haven’t changed much. Their jaw cavities have become<br />

larger for keeping more young in their mouths, and their<br />

colors are different, but that’s about it,” explains Professor<br />

David Bellwood, a researcher in the study.<br />

While other fishes have evolved by changing shape<br />

and broadening their diet, the mouthbrooding fishes remain<br />

simple feeders that eat mainly plankton. This can<br />

be bad news when food is scarce.<br />

With a lifespan of about two years, cardinalfishes<br />

breed several times a year, mostly in summer. Instead<br />

of laying thousands of eggs in a batch as other fishes do,<br />

they lay hundreds of slightly larger eggs. When the female<br />

releases the eggs, the male gathers them into a tight<br />

bundle, which he keeps safe in his mouth for a couple<br />

of weeks until the young hatch and become<br />

free-swimming.<br />

“These eggs occupy up to 100 percent<br />

of the oral cavity, and the dad’s<br />

mouth expands and looks like a large<br />

bubble,” says Dr. Andrew Hoey, who<br />

conducted the study. It’s a wonder that<br />

they can even breathe. They don’t feed,<br />

but live on stored energy and stay sedentary<br />

in and around corals.<br />

“The females play the role of jealous<br />

wives. They stay close to the males,<br />

not to help rear the kids, but to prevent<br />

other females from swimming off with<br />

such a desirable mate. Our guess is<br />

these stay-at-home dads are very much<br />

in demand.”<br />

Although the 50-million-year-old<br />

breeding technique has proved successful<br />

so far, providing large and happy<br />

families for cardinalfishes, their future<br />

is looking grim, Bellwood says.<br />

Apart from being left behind in<br />

terms of evolution, mouthbrooding<br />

makes them more vulnerable to the effects<br />

of climate change. “As ocean temperatures<br />

warm, these fishes will need to<br />

breathe more, and having a mouthful of<br />

offspring will hinder their ability to take<br />

in oxygen.” The other problem is the increasing<br />

lack of shelter as corals around<br />

the world die from bleaching and disease—cardinalfishes<br />

are popular prey for<br />

larger predatory fishes like coral trout.<br />

“These fishes are very attached to<br />

their homes; they like to stay under<br />

branching corals, and they come back to<br />

the same little patch day after day,” Bellwood<br />

says. He points out that branching<br />

corals are one of the types that are most<br />

vulnerable to climate change, so if they<br />

perish as a result of bleaching or disease,<br />

the cardinalfishes will be exposed and<br />

18 CORAL

Above: A male cardinalfish Siphamia<br />

argentea carries its young in its mouth.<br />

Right: Small eyes look out from the safety<br />

of a parent’s mouth: do cardinalfishes pay a<br />

price for good parenting? A male brooding<br />

Cheilodipterus sp.<br />

vulnerable. “When the coral cover declines,<br />

they’re going to be homeless, just<br />

sitting there with babies in their mouths<br />

and struggling to breathe. Their problems<br />

will be exacerbated by a shortage<br />

of food because of their narrow diets. In<br />

short, these stay-at-home dads have sacrificed<br />

job options, and even their lives,<br />

to provide top-notch parental care for<br />

their young. Just imagine what your life<br />

would be like if you had a toddler hanging<br />

from your teeth!<br />

“This has proved a highly successful<br />

survival strategy for 50 million years, but<br />

under rapid global warming, there is a big<br />

risk it could come unstuck. This is another<br />

example of the profound impact that<br />

humans are having on life on Earth.”<br />

KORALIA &<br />

SMARTWAVE<br />

CONTROLLER<br />

P U M P<br />

RUDIE KUITER<br />

REFERENCES:<br />

The paper, “To feed or to breed:<br />

morphological constraints of<br />

mouthbrooding in coral reef cardinalfishes,”<br />

by Andrew S. Hoey, David R. Bellwood, and<br />

Adam Barnett, appears in Proceedings of the<br />

Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.<br />

ON THE INTERNET:<br />

Hoey, A.S., D.R. Bellwood, and A. Barnett.<br />

2012. Proceedings of the Royal Society B:<br />

Biological Sciences, 2/8/12:<br />

http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/<br />

content/early/2012/02/06/rspb.2011.2679/<br />

suppl/DC1<br />

Atlantic current or Pacific flow?<br />

Smartwave & Koralia:<br />

your Aquarium has never been so natural.<br />

Smartwave helps recreate the natural currents that promote a healthy aquarium by<br />

controlling one or more pumps. Easy to use, with two different movement programs with<br />

exchange times between 5 seconds and 6 hours and two different feeding programs.<br />

Compact and energy saving, Koralia Pumps are ideal to recreate the natural and<br />

benefi cial water motion of rivers and seas in your aquarium. Koralia Pumps utilize patented<br />

magnet-suction cup support for easy and safe positioning and may be connected to a<br />

controller and set to intervals of seconds, minutes or hours.<br />

HYDOR USA Inc. Phone (916)920-5222 e-mail: hydor.usa@hydor.com www.hydor.com<br />

Designed in Italy<br />

CORAL<br />

19

Inspired<br />

by Mother<br />

Nature.<br />

Engineered by<br />

®<br />

Swiss or Hairy Commensal Shrimp—Sandimenes hirsutus<br />

It’s difficult to think of anything more unusual: this tiny partner shrimp<br />

from the South Pacific was previously completely unknown to us, and even<br />

the Internet has very few pictorial references for Sandimenes hirsutus. The<br />

specimen pictured here was probably an accidental import to Switzerland,<br />

where I found it at SwissAquaristik. In the absence of any alternative, and not<br />

entirely seriously, I have permitted myself to name it the Swiss Commensal<br />

Shrimp because of its bright red body color with white lines, the colors of the<br />

Swiss flag. Formerly known as Periclimenes hirsutus, this little shrimp, barely<br />

0.75 inches (2 cm) long, was given its own genus in 2009 to recognize the<br />

unusual tufts of setae on its body and appendages. It probably lives commensally<br />

with sea urchins in its natural habitat, possibly with the poisonous and<br />

equally attractive red Astropyga radiata.<br />

—Inken Krause<br />

ON THE INTERNET:<br />

http://www.chucksaddiction.com/car042.html<br />

20 CORAL<br />

www.ecotechmarine.com<br />

INKEN KRAUSE

EcoTech has you covered:<br />

Small.<br />

Medium.<br />

MP10<br />

Tanks less<br />

than 50<br />

gallons<br />

Large.<br />

No matter what size reef tank you enjoy, the winning i VorTech TM line of pumps has the solution.<br />

award-<br />

MP40<br />

Tanks with<br />

50-500+<br />

gallons<br />

The VorTech family boasts the smallest propeller pumps<br />

on the market when you consider how small of a<br />

footprint they have inside your aquarium.<br />

The superior design and technology produce<br />

unmatched broad-yet-gentle flow—one of many<br />

reasons VorTech has become the #1 family of pumps<br />

among true reef enthusiasts.<br />

MP60<br />

Tanks with<br />

120-1,000+<br />

gallons<br />

Elegantly Discreet. Highly Controllable. Incredibly Effective.<br />

®<br />

ecotechmarine.com<br />

CORAL<br />

21

Text & images by SCOTT W. MICHAEL<br />

Exquisite example<br />

of a Dragon Moray,<br />

Enchelycore pardalis, in<br />

the Izu Islands, Japan.<br />

The Dragon Moray<br />

Enchelycore pardalis<br />

There may be no other fish on a coral reef that is as menacing<br />

and beautiful as the Dragon Moray (Enchelycore<br />

pardalis). With its curved jaws, ever-bared teeth, and<br />

flaring, horn-like nostrils, it gives the impression that it<br />

is waiting for a chance to strike, to sink its razor-sharp<br />

fangs into you—or some unsuspecting fish passing by.<br />

But this malevolent countenance is offset by an alluring<br />

color pattern that includes dark-edged spots,<br />

bands, and, in some individuals, flaming orange pigment<br />

that would make any designer of Aloha Hawaiian<br />

shirts proud. Its relative rarity in areas where most fish<br />

collecting occurs, as well as its ornate physique and the<br />

resulting demand for it among advanced aquarists, has<br />

made the Dragon Moray a pricey acquisition. But unlike<br />

some of the rarest, most unique marine species, such<br />

as the Rhinopias scorpionfish (see CORAL, March/April<br />

2012), this animal is relatively easy to keep and can live<br />

for many years in captivity.<br />

Here we will look at the scant information available<br />

on the natural history of this distinctive moray, as well<br />

as explore how to best keep this muraenid beauty in your<br />

home aquarium.<br />

DRAGONS IN THE FIELD<br />

Relatively little is known about the life history of Enchelycore<br />

pardalis. It is wide-ranging, occurring from Zanzibar<br />

22 CORAL

EASY CARE AND MAINTENANCE<br />

AQUARIUM TOOLS<br />

SIMPLE SOLUTIONS, BIG IMPACT<br />

Fish and Pest Traps<br />

Gravel Cleaner Set<br />

Magnet Cleaners<br />

Aquarium Scraper<br />

Filter Bags<br />

Magnet Cleaner<br />

Tweezers<br />

Many more at: www.aqua-medic.com<br />

Filter Bags<br />

Gravel Cleaner<br />

Fish Trap<br />

Scraper<br />

www.aqua-medic.com<br />

Sales: 970.776.8629 877.323.2782 Fax: 970.776.8641 Email: sales@aqua-medic.com<br />

Sales: 970.776.8629 / 877.323.2782 | Fax: 970.776.8641 | Email: sales@aqua-medic.com<br />

CORAL<br />

23

off the coast of East Africa, east to the Hawaiian and<br />

Marquesas Islands, north to southern Japan, and south<br />

to New Caledonia, off northeastern Australia. But while<br />

it has an expansive distribution, it is reportedly scarce<br />

over much of its known range. I had been diving for decades<br />

before encountering one of these amazing morays<br />

in situ. It wasn’t for lack of trying—they are just not that<br />

common in the areas where most people go to observe<br />

and photograph fishes.<br />

Then I was asked to escort<br />

a good friend of mine, underwater<br />

photographer extraordinaire<br />

Roger Steene, to Osezaki<br />

and the Izu Islands in Japan.<br />

On my first shore dive at Osezaki,<br />

I saw a relatively blandcolored<br />

E. pardalis and was<br />

“gutted” when I realized I was<br />

out of film (yes, it was back<br />

in the age of film, which some<br />

of us still refuse to let fade).<br />

Although it had been an excellent<br />

dive prior to this moment,<br />

I came out of the water<br />

grumbling, because I was sure<br />

I had missed my only opportunity<br />

to photograph this eel<br />

in the wild. But, boy, was I<br />

wrong! Over the next several<br />

weeks we saw more than 50<br />

Dragon Morays. In fact, this<br />

species, along with the Kidako<br />

Moray (Gymnothorax kidako),<br />

were the most common muraenids<br />

we encountered.<br />

In southern Japan, the<br />

preferred habitat of E. pardalis<br />

is boulder-strewn bottoms.<br />

They refuge within the interstices<br />

among large corallineencrusted<br />

boulders. During<br />

my weeks in southern Japan,<br />

I also saw these morays partially<br />

hidden between smaller<br />

rocks, in crevices under limestone<br />

overhangs, and in large<br />

fissures in large rocky pinnacles<br />

and outcroppings. In<br />

other locations (for instance,<br />

in the Hawaiian Islands), they<br />

are reported to live among<br />

branching Porites corals.<br />

In the majority of cases,<br />

only the head of the Dragon<br />

is seen protruding from its<br />

refuge. It is likely that most<br />

relocation and hunting occurs after dark. The younger<br />

E. pardalis are apparently even more cryptic than larger<br />

conspecifics—they are rarely seen or collected. Off southern<br />

Japan, I observed the Dragon Moray at depths of 5<br />

to 88 feet (1.5 to 27 m); however, it has been reported<br />

down to depths of 163 feet (50 m). Hawaiian underwater<br />

photographers Keoki and Yuko Stender say the species<br />

is “relatively rare at scuba depths around the main<br />

Dragon Moray sharing its<br />

lair with a Banded Coral<br />

Shrimp. Note the eel’s<br />

jaws, which become more<br />

elongated as it grows.<br />

24 CORAL

Hawaiian Islands, but common in the cooler waters of<br />

the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.”<br />

These eels usually live a solitary life style. While I<br />

never saw them sharing a “hide,” I occasionally have<br />

found more than one within “spitting distance” of others.<br />

Nothing is known about the spawning behavior of<br />

this eel, nor is information available on its diet in the<br />

wild. The large mouth and long, sharp teeth are indicative<br />

of a piscivorous diet. There are also reports in the<br />

popular literature, including my own book (Michael<br />

1998), that this species relishes cephalopods (namely,<br />

octopuses). While this is likely, once again I have yet to<br />

find food habit studies that confirm it.<br />

These morays may look too fearsome for most predators<br />

to tackle, but young Dragons are eaten by sea kraits<br />

(Laticauda spp.). These amphibious snakes have small<br />

heads, which they use to probe into reef crevices and<br />

holes and extract hiding morays. In fact, there are a<br />

number of species in the genus Laticauda that specialize<br />

in eating conger and moray eels.<br />

DRAGON CARE<br />

As noted above, price will dissuade most aquarists from<br />

keeping one of these eels, but for those who are willing<br />

to drop some Benjamins, there are some things you<br />

will want to bear in mind before making the investment.<br />

One of the first things to consider is whether you are going<br />

to keep the eel on its own or with other fishes. I think<br />

these eels are spectacular enough to hold<br />

their own in a species aquarium. You<br />

will want to house a solitary, full-grown<br />

E. pardalis in a tank of 75 to 135 gallons<br />

(284–511 L).<br />

If you are going to keep your Dragon<br />

with other fishes, it is imperative that<br />

the tank be large enough and that you<br />

select tankmates very carefully. This is<br />

important not only for the well-being of<br />

the moray’s tankmates, but also for the<br />

Dragon itself. You need a tank of at least<br />

180 gallons (681 L) for a fish community<br />

tank that contains a medium-sized E.<br />

pardalis. If you have a full-grown Dragon<br />

Moray, the tank should be even larger<br />

(minimum of 240 gallons, or 908 L). The<br />

more room there is, the more likely the<br />

eel and its tankmates are going to live in<br />

harmony. Of course, in addition to a sizable<br />

aquarium, the moray and its tankmates<br />

will need adequate filtration to<br />

handle the bioload.<br />

Larger fishes make the best Dragon<br />

neighbors—the body depth of the potential<br />

tankmates should be at least twice<br />

that of the eel’s girth. Possible Dragon<br />

tankmates include groupers, snappers,<br />

grunts, sweetlips, batfishes, large surgeonfishes,<br />

and rabbitfishes. Dragons do<br />

have a mixed reputation when it comes to<br />

“playing well with others.” For example,<br />

the company I work for keeps a 30-inch<br />

(76-cm) Dragon in a large tank with medium-to-large<br />

fishes, and it rarely, if ever,<br />

has caused problems. In fact, we have not<br />

been able to attribute any fish death to<br />

the eel.<br />

That said, I have seen them knock off<br />

or injure sizable piscine tankmates. I certainly<br />

wouldn’t trust this moray enough<br />

to keep it with a prized Pygmy Angelfish<br />

26 CORAL

ONLY POLY-FILTER®AND KOLD STER-IL®FILTRATION PROVIDES SUPERIOR WATER<br />

QUALITY FOR OPTIMAL FISH & INVERTEBRATE HEALTH AND LONG-TERM GROWTH.<br />

POLY-FILTER®- THE ONLY CHEMICAL FILTRATION MEDIUM THAT ACTUALLY<br />

CHANGES COLOR. EACH DIFFERENT COLOR SHOWS CONTAMINATES, POLLUTANTS<br />

BEING ADSORBED & ABSORBED. FRESH, BRACKISH, MARINE AND REEF INHABITANTS<br />

ARE FULLY PROTECTED FROM: LOW pH FLUCTUATIONS, VOCs, HEAVY METALS,<br />

ORGANIC WASTES, PHOSPHATES, PESTICIDES AND OTHER TOXINS. POLY-FILTER®IS<br />

FULLY STABILIZED – IT CAN’T SORB TRACE ELEMENTS, CALCIUM, MAGNESIUM,<br />

STRONTIUM, BARIUM, CARBONATES, BICARBONATES OR HYDROXIDES.<br />

USE KOLD STER-IL®TO PURIFY YOUR TAP WATER. ZERO WASTE! EXCEEDS US EPA & US<br />

FDA STANDARDS FOR POTABLE WATER. PERFECT FOR AQUATIC PETS, HERPS, DOGS,<br />

CATS, PLANTS AND MAKES FANTASTIC DRINKING WATER. GO GREEN AND SAVE!<br />

117 Neverslnk St. (Lorane)<br />

Reading, PA 19606-3732<br />

Phone 610-404-1400<br />

Fax 610-404-1487<br />

www.poly-bio-marlne.com<br />

POLY-BIO-MARINE, INC. ~ EST. 1976

Dragon Moray: colors can<br />

range from bright orange<br />

to muted brown and tan<br />

tones.<br />

or fairy wrasse. Long, skinny fish are certainly going to be<br />

ingested by your moray. Also remember that morays often<br />

cue in on and attack fishes that are injured or stressed.<br />

In the case of larger fishes, a Dragon Moray may engage<br />

in “knotting” behavior, which looks similar to a python<br />

constricting its prey. This enables the eel to compress the<br />

prey item’s body so it can swallow it whole, or, if it is too<br />

large to ingest, to rip chunks from the larger prey item.<br />

Beware: some large fish species that are often considered<br />

suitable Dragon neighbors may turn the tables and injure<br />

your moray. Large triggers, puffers (Arothron spp.), and<br />

porcupinefishes have been known to bite at morays—especially<br />

at a tail protruding from the rockwork.<br />

What about keeping a Dragon with other morays?<br />

This is potentially risky, but less so than housing them<br />

with other fishes. There are other morays that will eat<br />

Dragon Morays, namely the Honeycomb Moray (Gymnothorax<br />

favagineus) and the Spotted Moray (G. moringa).<br />

Dragon Morays are not likely to eat other morays,<br />

but they may bite at them when defending a preferred<br />

refuge or competing for food. Their large teeth can inflict<br />

serious wounds on other eels. Morays introduced after<br />

a Dragon Moray has made itself at home are especially<br />

likely to end up with some puncture wounds, but even<br />

resident morays may elicit this eel’s wrath if they are slow<br />

to give up a preferred hiding place. I have seen other eels<br />

that were nearly as long as the Dragon Moray (and well<br />

established in the tank before the E. pardalis was added)<br />

flee to the upper corner of the tank when threatened by<br />

one of these menacing-looking beasts. The threat display<br />

of the Dragon Moray is spectacular—it opens its jaws as<br />

wide as possible, laterally flattens the gill region, cocks its<br />

head to one side, and erects its dorsal fin. The key to keeping<br />

it with other morays is to provide plenty of hiding<br />

places. This means more than one for each moray kept.<br />

Like most morays, the Dragon wants an appropriate<br />

hide in which to refuge during the day. The size of the<br />

caves and crevices are obviously a function of the eel’s<br />

girth and length, so you will have to construct hiding<br />

places accordingly. I am all about natural, so I like to use<br />

live rock (or some of the beautiful faux rock that looks<br />

as though it is encrusted with coralline algae) to create<br />

28 CORAL

Photo courtesy of Georgia Aquarium<br />

<br />

<br />

Instant Ocean. The number one choice of Georgia Aquarium, John G. Shedd Aquarium,<br />

Dallas Zoo and over 75 others.<br />

Why do celebrated public aquariums choose Instant Ocean® Sea Salt?<br />

It’s simple. Instant Ocean is the most precisely formulated sea salt in the<br />

world—and delivers the highest level of product consistency.<br />

We’re proud to have earned the confidence of more than 75 world-class<br />

aquariums, zoos and research facilities.<br />

Bring the confidence home. Trust Instant Ocean’s quality and<br />

consistency to keep your own aquarium’s precious marine life healthy.<br />

Available at your favorite pet or fish retailer.<br />

<br />

www.instantocean.com 800-822-1100 visit us on<br />

© 2012 Instant Ocean<br />

Bringing the ocean home.<br />

CORAL<br />

29

30 CORAL

eef structure. One thing to keep in mind when creating<br />

a Dragon lair is that they have been known to dig under<br />

rockwork by rapidly swishing the tail back and forth,<br />

causing unstable rockwork to cave in. If the rocks are<br />

large enough, they could harm the moray when they collapse.<br />

Place the rockwork on the bottom of the tank (not<br />

on top of the sand bed), using cable ties and putty epoxy<br />

to create sturdy hides. (The Real Reef company creates<br />

awesome-looking rock that looks coralline-encrusted<br />

and is bioactive. They can custom-make fantastic, sturdy<br />

caves for your moray.) Some hardcore moray keepers<br />

prefer PVC pipe of varying diameters. If your Dragon eel<br />

is fully acclimated (eating voraciously), you can take out<br />

some of the rockwork so you can better observe your muraenid<br />

charge. I have seen individuals kept in tanks with<br />

lots of faux coral that only showed themselves when<br />

food was added to the tank.<br />

A newly acquired Dragon Moray will spend much of<br />

its time hiding within the structure of the reef. In fact, if<br />

you have created suitable hiding places, you may not see<br />

much of it for the first week or so. If a moray does not feel<br />

comfortable, it is not likely to eat. So, if your new moray<br />

is refusing food, you should provide more or better hiding<br />

places in order to ensure it “feels” comfortable in its<br />

new home. Other things that can cause fasting are poor<br />

water quality, other fishes (puffers, triggers) picking at<br />

the moray, or overfeeding for an extended period of time.<br />

Long fasts are usually not a great cause of concern, but<br />

it is not a bad idea to do a water change and try different<br />

foods if the eel does not eat for more than a month.<br />

Most Dragon Morays will eat non-living food. The<br />

best foods are strips of fish flesh (such as smelt, orange<br />

roughy, or haddock) and squid. Impale the food on the<br />

end of a feeding stick (a length of rigid airline with a<br />

sharpened end to pierce the food will do) and move it<br />

in front of the eel’s head. One thing we moray lovers<br />

are prone to doing that is not good for our eels is to<br />

feed them too often. This leads to an accumulation of fat<br />

that can affect liver function. Field studies suggest that<br />

morays eat infrequently, so in order to prevent this condition<br />

I recommend feeding your eel to satiation twice a<br />

week. Also, an overfed moray may regurgitate its partially<br />

digested meal, which can make a mess of your tank.<br />

On rare occasions, a frisky Dragon Moray, possibly<br />

incited by the presence of food, may snap at passing fish<br />

(even those too large to swallow) and cause injuries. I<br />

find that controlled food presentation—that is, putting<br />

food in front of the moray’s face with tongs or a feeding<br />

stick—is the best way to keep the eel calmer. Throwing<br />

live feeder fish in the tank is more likely to make the<br />

moray dart about and indiscriminately snap at passing<br />

tankmates.<br />

The Dragon Moray can be kept in a reef tank if you<br />

are willing to put up with the mechanical damage it may<br />

cause to your corals. The best way to prevent this is to<br />

make sure the corals are firmly affixed to the larger rock-<br />

Are you attached to your corals?<br />

Corals are not only beautiful, they’re precious. You really have to give them a secure<br />

attachment because bonding with corals promotes a long-term relationship.<br />

Two Little Fishies AquaStik Coralline Red and Stone Grey are underwater epoxy puttys<br />

with clay-like consistency for easy attachment of corals. Their natural colors blend with<br />

rock. Both colors are available in 2oz and 4oz sizes.<br />

CorAffix is an ethyl cyanoacrylate bonding compound with viscosity similar to honey.<br />

Use it for attaching stony corals, gorgonians, and other sessile invertebrates in natural<br />

positions on live rock, or use in combination with AquaStik to attach larger coral heads.<br />

CorAffix Gel is an ethyl cyanoacrylate bonding compound with a thick gel consistency.<br />

It is very easy to use for attaching frags of stony corals, zoanthids, and some soft corals to<br />

plugs or bases.<br />

AquaStik, CorAffix, and CorAffix Gel<br />

work on dry, damp, or wet surfaces,<br />

cure underwater, and are non-toxic to<br />

fish, plants and invertebrates.<br />

Developed by aquarium expert<br />

Julian Sprung.<br />

Two Little Fishies<br />

Advanced Aquarium Products<br />

www.twolittlefishies.com<br />

CORAL<br />

31

work. The Dragon Moray may also eat some motile invertebrates<br />

(namely ornamental crustaceans), but they<br />

can be kept with cleaner shrimps (Lysmata amboinensis,<br />

L. debelius) and boxing shrimps (Stenopus hispidus). It is<br />

best to acclimate these shrimps to the aquarium before<br />

adding the moray.<br />

PRECAUTIONS<br />

A few final words of caution to anyone thinking about<br />

keeping a moray: These animals are the Houdinis of the<br />

bony fish world. They will slip out of any opening in the<br />

aquarium top and end up dried up on the floor (possibly<br />

many feet from their aquarium home). Larger individuals<br />

have even been implicated in pushing the glass top<br />

off a tank before making their escape. Any moray aquarium<br />

should have a secure top with no escape holes; put<br />

something heavy on the top (I have used dive weights) if<br />

you are keeping a larger specimen. They have also been<br />

known to slip into corner overflow boxes and wind up on<br />

the pre-filter in the sump or in the sump itself.<br />

Then there is the issue of being bitten by your pet<br />

Dragon. This species is not known for aggressive behavior<br />

in the wild, but it can inflict serious puncture and<br />

slash wounds if not treated with respect. Any eel bite<br />

wound should be cleaned and washed with warm water<br />

and soap; rubbing alcohol and hydrogen peroxide are no<br />

longer recommended for first aid treatment of cuts and<br />

bites. You may wish to rinse the wound with a sterile saline<br />

solution and use an antibiotic ointment or rinse. If<br />

the bite is deep, medical attention should be sought. The<br />

worst outcome from a minor moray bite is usually an<br />

infection triggered by bacteria in the eel’s mouth; such<br />

an infection can become serious or even prove fatal if<br />

not treated.<br />

Bites should be easy to avoid: never, ever hand-feed<br />

an eel, and generally follow the rule about keeping your<br />

hands out of the tank. Use long-handled tools to feed<br />

and move items in the tank. If you need to reach in, consider<br />

using a long-handled net of an appropriate size as a<br />

screen to block the eel from attacking. Most eel bites in<br />

aquariums result from the moray instinctively defending<br />

its territory or mistaking a finger for a food item.<br />

While they are not for everyone, a Dragon Moray can<br />

make a stunning display animal and a fascinating pet.<br />

If you take the necessary precautions and practice good<br />

aquarium husbandry, your Dragon should happily dwell<br />

in its aquarium lair for many years.<br />

REFERENCES<br />

Michael, S.W. 1998. Reef Fishes, Volume 1. Microcosm/TFH,<br />

Neptune City, New Jersey.<br />

ON THE INTERNET:<br />

Keoki and Yuko Stender’s Marinelife Photography:<br />

http://www.marinelifephotography.com/fishes/eels/<br />

enchelycore-pardalis.htm<br />

32 CORAL

thrIVE<br />

CORAL<br />

33

opinion by MATT PEDERSEN<br />

POINT<br />

The Aquarium Ark<br />

Can marine aquarists provide a safety net<br />

for endangered species and aquatic diversity?<br />

The first time I publicly expressed my concerns for the future of coral<br />

reefs, I got a bit choked up and teary-eyed. Standing in front of a small<br />

gathering of marine fish breeders, I said that I wanted to make sure<br />

my children, when I had them, would be able to experience the coral<br />

reef life forms and species we all treasure. It was embarrassing—a guy<br />

about to start his fourth decade on the planet, getting emotional in<br />

front of a group of people he had just met.<br />

The author with<br />

an invasive<br />

lionfish in the<br />

Florida Keys.<br />

Years later, I’m married and that hypothetical child is my son, Ethan. As the father of an<br />

enchanting young soul whom I come to appreciate more each day, I ask myself again—will<br />

it all be here when he’s old enough to appreciate it? The short answer is that it depends on<br />

what we marine aquarists collectively do next.<br />

With the cacophony of anti-marine-aquarium sentiment raging all over the country, it<br />

is amazing to contemplate that there’s an entire “second” hobby out there that is at least 10<br />

times bigger and easily more than twice as old, probably harvesting more wild fish (in volume)<br />

each year than ours—yet no one is attacking it. Walk into any store that sells live<br />

tropical aquarium fish and, chances are, you’ll be offered the opportunity to purchase<br />

a species that is at risk, endangered, or even extinct in the wild. Yet there’s no public<br />

outrage, no call to stop the trade in these fishes. You don’t need any special permits to<br />

own them, and no one will hold you in contempt if you accidentally kill them.<br />

Many freshwater fish species are being commercially bred on fish farms, most notably<br />

in Southeast Asia and Florida. Other, less popular species are being bred by a few<br />

individual aquarists who are working, without grants or funding of any sort, to preserve<br />

our planet’s bioheritage. Some species owe their very existence to these volunteer<br />

preservationists. In truth, the freshwater aquarium hobby and industry is a modernday<br />

ark—the last chance for many fish species. What will the marine aquarium hobby<br />

learn from all this?<br />

IST<br />

AQUARIUMS—LUXURIES FOR THE RICH?<br />

There’s no question that keeping a home aquarium is a luxury. Think about it: if you’re<br />

reading this, you probably live in one of the better-off areas of the world. You’re probably<br />

not worried about where your next meal will come from or how you’ll pay for it.<br />

In a world of humanitarian priorities, research funding goes to food-fish culture. We’re far<br />

more concerned about putting protein in people’s bellies than putting fishes in their aquari-<br />

Matt Pedersen is a CORAL senior editor and lives in Duluth, Minnesota.<br />

MATTHEW L. WITTENRICH<br />

34 CORAL

ILLUSTRATION: JOSHUA HIGHTER<br />

ums. For many years now, active aquarists have sensed<br />

that sooner or later, the marine aquarium industry<br />

would become a target of off-kilter environmentalists.<br />

Whether or not the aquarium industry is actually causing<br />

problems, it is highly visible and completely unnecessary<br />

for the basic daily survival of most human beings.<br />

People connect with the fish we keep in our aquariums<br />

on a very emotional level. Children don’t find<br />

Bluefin Tuna particularly cute, but a clownfish stops<br />

them in their tracks. So for someone looking to say they<br />

did something to change the future of our oceans, the<br />

marine aquarium industry—the purpose of which is to<br />

put fishes in tanks just to look at them—makes the perfect<br />

scapegoat. The activist who wants to think she did<br />

something to help can sleep soundly at night, believing<br />

that whether shutting down the aquarium fishery actually<br />

changes anything or not, at least she tried.<br />

AQUARIUMS AND REAL PEOPLE<br />

If we dig deeper, we realize that the aquarium hobby is<br />

not just a luxury pastime. Far from it: It is based on<br />

a multi-million-dollar industry that provides incomes<br />

for untold numbers of people. The indigenous collectors<br />

of wild fishes for aquarium use derive an income from<br />

the fishery that otherwise would be unavailable to them.<br />

Catching damselfishes or wrasses, useless for food, puts<br />

money into their meager household budgets to buy food<br />

for their tables and school supplies for their kids.<br />

Proponents of sustainable aquarium fisheries are<br />

quick to point out that without these aquarium fisheries,<br />

those collectors would turn to more destructive fishing<br />

activities, such as “blast fishing” for edible species.<br />

But despite the many benefits that humankind derives,<br />

in the eyes of those who hate us the costs and possible<br />

negative impacts of aquarium keeping are unjustified.<br />

The truth is that for some fish species, aquariums<br />

aren’t luxuries; they are saviors.<br />

THE ARK IN THE AQUARIUM<br />

Breeding is one of the cornerstones of the freshwater<br />

aquarium hobby, and the majority of freshwater aquarium<br />

fishes are now cultured. Many that are commonplace<br />

in aquarium shops are threatened, endangered, or<br />

even extinct in the wild.<br />

The poster child is a fish I first learned about a few<br />

years ago, the Redtail Shark (Epalzeorhynchos bicolor,<br />

formerly Labeo bicolor). Up until recently, the IUCN Red<br />

List considered this fish extinct in the wild. That status<br />

has been changed to “critically endangered” for the moment—yet<br />

you can walk into any tropical fish shop and<br />

see several of these for sale. Large fish farms in Asia are<br />

rearing huge numbers of this species.<br />

Anti-aquarium activists hear a story like this and often<br />

assume that the aquarium industry is to blame for<br />

the demise of wild populations. Original IUCN writeups<br />

suggested that the cause was a combination of pollu-<br />

CORAL<br />

35

36 CORAL

CORAL<br />

37

tion and “much needed” dams that were built without<br />

regard for the impact they would have on fish. (IUCN<br />

has tempered the wording, and now lists the likely cause<br />

as “habitat modification.”) It appears that the Redtail<br />

Shark is a victim of human population growth and is<br />

being saved only because we happen to find it attractive.<br />

Another ubiquitous species, the White Cloud<br />

Mountain Minnow (Tanichthys albonubes), is listed<br />

Redtail Shark,<br />

Epalzeorhynchos<br />

bicolor<br />

Endler’s Livebearer, Poecilia wingei:<br />

both of these species are being preserved by aquarium breeding.<br />

on the IUCN Red List—currently as “data deficient”<br />

but formerly as “extinct in the wild,” according to the<br />

C.A.R.E.S. Preservation Program’s citation of its IUCN<br />

status. Despite this, it is one of the undisputed best “beginner<br />

fish,” as it is able to thrive in both unheated and<br />

heated aquariums, easy to breed, extremely resilient,<br />

and quite attractive. This species is not going anywhere<br />

as long as people continue to keep aquariums. I would<br />

be genuinely shocked to walk into an aquarium store<br />

and not encounter one of the many flamboyant variants<br />

of the White Cloud now being offered.<br />

Even though I’ve been aware of the plight of Redtail<br />

Sharks and White Cloud Mountain Minnows, I was surprised<br />

to learn that C.A.R.E.S. considers even the commonly<br />

available Boesmani Rainbowfish (Melanotaenia<br />

boesemani), endemic to only three lakes in Irian Jaya,<br />

Indonesia, to be either at risk or endangered in the wild<br />

(the IUCN lists it as endangered). Even so, I could have<br />

a guilt-free colony of Boesmani Rainbowfish at my doorstep<br />

within a week’s time. This is all possible because of<br />

captive propagation.<br />

DOMESTICATION HAPPENS<br />

Other species are not so lucky. The livebearers are a<br />

group of very popular aquarium fishes that are farmed<br />

in large numbers. However, many of the swordtails and<br />

platies and guppies that we see in every shop are not<br />

what we think they are.<br />

The great majority of them are domesticated forms<br />

that have been selectively bred for decades—a hybrid<br />

cocktail of numerous closely related wild species.<br />

To put this in perspective, the average<br />

swordtail or guppy is the equivalent of the<br />

Snow Onyx or Black Photon designer clownfish.<br />

What’s at risk in the livebearer world<br />

isn’t the next Platinum Percula; it’s the good<br />

old original wild forms—the classic Ocellaris<br />

Clownfish from salt water, Endler’s Livebearer<br />

from fresh water, the natural “default” colorations<br />

and forms of species from which all our<br />

domesticated forms were derived.<br />

Just as Ocellaris and Percula Clownfish<br />

have “cousins” that are rare or unpopular in<br />

the trade, so do the livebearers. These cousins<br />

of the guppies and swordtails don’t share the<br />

relative safety offered by commercial popularity.<br />

They are hanging on only because dedicated<br />

aquarists see the value of natural forms<br />

that wouldn’t stand a chance of capturing the<br />

casual hobbyist’s superficial tastes.<br />

Ameca splendens, the Butterfly Goodeid, is<br />

considered extinct in the wild by C.A.R.E.S.,<br />

Fishbase, and the IUCN. However, according<br />