A Gendered Analysis of the Social Protection Network in ... - CISAS

A Gendered Analysis of the Social Protection Network in ... - CISAS

A Gendered Analysis of the Social Protection Network in ... - CISAS

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Introduction<br />

A <strong>Gendered</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Social</strong><br />

<strong>Protection</strong> <strong>Network</strong> <strong>in</strong> Nicaragua<br />

Sarah Bradshaw and Ana Quirós Víquez 1<br />

Draft October 2003 not to be cited without authors permission<br />

The Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSP) <strong>in</strong>itiative has been promoted as mark<strong>in</strong>g<br />

a new policy era for <strong>the</strong> World Bank and International Monetary Fund. 2 The World<br />

Bank highlight and reiterate that <strong>the</strong>re is no ‘bluepr<strong>in</strong>t’ for PRSPs stress<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong>y are<br />

country owned and produced through participatory processes. However a review <strong>of</strong><br />

PRSPs to date show similarities <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir central components with most<br />

conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g four central elements; economic growth, <strong>in</strong>vestment <strong>in</strong> human<br />

capital, social safety nets, and good governance. In addition issues such as gender and<br />

<strong>the</strong> environment are mentioned with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> documentation, most usually as ‘cross-cutt<strong>in</strong>g’<br />

<strong>the</strong>mes. This paper considers social safety nets <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Nicaraguan context through a<br />

gendered analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Social</strong> <strong>Protection</strong> <strong>Network</strong> (Red de Protección <strong>Social</strong> - RPS) <strong>the</strong><br />

pilot phase <strong>of</strong> which has recently evaluated prior to its wider implementation.<br />

Gender <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Poverty Reduction Strategy Framework<br />

Increas<strong>in</strong>gly World Bank economists are recognis<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> importance <strong>of</strong> political and<br />

social factors as be<strong>in</strong>g essential to <strong>the</strong> success <strong>of</strong> macroeconomic policy <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g<br />

countries. The emerg<strong>in</strong>g view is that <strong>the</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> success <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> past <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> poverty<br />

reduction rates, <strong>in</strong>debtedness and economic growth are partly due to social and political<br />

problems ra<strong>the</strong>r than economic ones (see Collier and Dollar 2001 and 2002; Easterly,<br />

2002; Hanlon, 2000; Hout, 2002; Neumayer, 2002; Roodman, 2001). This view suggests<br />

<strong>the</strong> need to improve <strong>the</strong> policy mix and that development assistance should <strong>in</strong>clude not<br />

only ‘advice’ on economic policy but also advice on <strong>the</strong> good governance <strong>of</strong> that policy.<br />

A second recent research focus has been on <strong>the</strong> relationship between economic growth<br />

and gender equality (see Dollar and Gatti 1999; Klasen 1999 and Kabeer 2003 for<br />

debate). Most central has been evidence to suggest that ensur<strong>in</strong>g more equal access to<br />

education for girls, that is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g women’s human capital potential, could impact<br />

positively on economic growth. At <strong>the</strong> same time it could also have a beneficial impact<br />

on fertility thus reduc<strong>in</strong>g population growth and fur<strong>the</strong>r enhanc<strong>in</strong>g economic growth<br />

ga<strong>in</strong>s. This work has partly <strong>in</strong>formed <strong>the</strong> Bank’s recent ‘Gender Ma<strong>in</strong>stream<strong>in</strong>g Strategy’<br />

which highlights <strong>the</strong> additional opportunities for economic growth and possibilities to<br />

“capitalize” on <strong>the</strong> opportunities that a reduction <strong>in</strong> gender-related barriers could br<strong>in</strong>g<br />

(World Bank 2001a: xii). Such f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs appear to have <strong>in</strong>formed <strong>the</strong> emerg<strong>in</strong>g PRSP<br />

process. For example, <strong>the</strong> gender section <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> World Bank’s PRSP Source Book<br />

1 Sarah Bradshaw - Middlesex University / International Cooperation for Development, UK.<br />

Ana Quirós Víquez - <strong>CISAS</strong> / Civil Coord<strong>in</strong>ator (CC), Nicaragua. The views expressed <strong>in</strong> this document<br />

are <strong>the</strong> authors own and do not necessarily reflect <strong>the</strong> op<strong>in</strong>ions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> organisations for which <strong>the</strong>y work.<br />

The authors would like to thank Brian L<strong>in</strong>neker for his useful comments on earlier drafts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> document.<br />

2 The production <strong>of</strong> a PRSP is a condition for future <strong>in</strong>ternational concessionary lend<strong>in</strong>g and debt relief<br />

from <strong>the</strong> two key International F<strong>in</strong>ancial Institutions (IFIs) to countries identified as eligible for <strong>the</strong><br />

Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC II) <strong>in</strong>itiative.<br />

1

highlights that “gender-sensitive development strategies contribute significantly to<br />

economic growth as well as to equity objectives” (Bamberger et al 2001: 3 emphasis<br />

added).<br />

While not<strong>in</strong>g that equality should be a “development objective <strong>in</strong> its own right” (World<br />

Bank 2001b: 1) <strong>the</strong> newfound <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> gender may <strong>the</strong>n be seen to have an ‘efficiency’<br />

ra<strong>the</strong>r than an ‘equity’ basis. This may result <strong>in</strong> an emphasis not only on economic<br />

growth ga<strong>in</strong>s, but on macro level economic ga<strong>in</strong>s. This means that <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual costs<br />

<strong>of</strong> such ga<strong>in</strong>s, and <strong>the</strong> extent to which such ga<strong>in</strong>s accrue to <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividuals who have<br />

contributed to <strong>the</strong>m, are largely ignored. Such an approach may use women to ga<strong>in</strong><br />

macro level growth goals, while not improv<strong>in</strong>g women’s micro level situations, or while<br />

reduc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir well be<strong>in</strong>g, as was <strong>the</strong> case with <strong>the</strong> Structural Adjustment Programmes <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> past (see Elson 1995). Even when women ga<strong>in</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ancially <strong>in</strong> this scenario <strong>the</strong><br />

narrow economic focus means that o<strong>the</strong>r possible costs may be ignored, as for example<br />

when women’s <strong>in</strong>comes <strong>in</strong>crease via waged labour <strong>in</strong> a factory that at <strong>the</strong> same time puts<br />

at risk <strong>the</strong>ir health. Accept<strong>in</strong>g that women’s relative poverty is experienced as social not<br />

just economic <strong>in</strong>equality means that an improvement <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> economic situation does not<br />

necessarily br<strong>in</strong>g about a decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> ‘poverty’.<br />

A recent review <strong>of</strong> PRSPs (see Zuckerman 2001; 2002) notes a fur<strong>the</strong>r conceptual<br />

problem <strong>in</strong> that those PRSPs that have attempted to <strong>in</strong>clude gender have taken a Women<br />

<strong>in</strong> Development (WID) ra<strong>the</strong>r than a Gender and Development (GAD) approach. The<br />

WID approach sees <strong>the</strong> ‘problem’ <strong>of</strong> development for women is <strong>the</strong>ir exclusion from <strong>the</strong><br />

process (see Suanders 2002 for discussion). The proposed <strong>in</strong>clusion <strong>of</strong> women <strong>in</strong><br />

development has tended to focus on <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>corporation <strong>in</strong>to education and formal sector<br />

employment. What WID does not do is critique <strong>the</strong> development process itself, see<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong>clusion as hav<strong>in</strong>g purely positive ‘development’ outcomes. It also does not consider<br />

<strong>the</strong> underly<strong>in</strong>g reasons for women’s exclusion and as such <strong>the</strong> unequal power relations<br />

on which it is based rema<strong>in</strong> unchallenged. In contrast a GAD approach starts from an<br />

analysis <strong>of</strong> exist<strong>in</strong>g gender roles and relations and seeks to challenge <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

In terms <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Nicaraguan PRSP, no specific proposals around gender are <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> PRSP, but it does <strong>in</strong>clude specific references to women. Where mentioned, women<br />

are presented as mo<strong>the</strong>rs, <strong>in</strong> both <strong>the</strong>ir car<strong>in</strong>g and reproductive roles, and also as ‘victims’<br />

<strong>of</strong> male abandonment and violence. In contrast very little mention is made <strong>of</strong> women as<br />

producers and <strong>in</strong>come generators. Women’s fertility is also central with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Nicaraguan PRSP, s<strong>in</strong>ce population growth may effectively cancel out any economic<br />

growth ga<strong>in</strong>s. The focus not only places <strong>the</strong> responsibility for reproduction with <strong>the</strong><br />

woman alone, it also highlights <strong>the</strong> need for ‘responsible’ reproduction as targets such as<br />

improv<strong>in</strong>g access to family plann<strong>in</strong>g for ‘women with a partner’ suggests. Although<br />

women are <strong>the</strong> specific target <strong>of</strong> fertility programmes, more generally <strong>the</strong>y are <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> strategy as <strong>the</strong> means by which specific targets can be reached – <strong>the</strong> mechanism by<br />

which goods and services can be provided to <strong>the</strong> family and more specifically children.<br />

Civil society has been analys<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> PRSP process s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g (see CCER 2001;<br />

Quirós Víquez 2002). A gendered analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> PRSP process has also been on go<strong>in</strong>g<br />

and <strong>the</strong> shortcom<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>al policy document have been presented both nationally<br />

and <strong>in</strong>ternationally (see Quirós Víquez et al 2002). However, to date little attention has<br />

been paid to <strong>the</strong>se evaluations and pilot projects have gone ahead without tak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to<br />

account <strong>the</strong> concerns raised. The <strong>Social</strong> <strong>Protection</strong> <strong>Network</strong>, <strong>the</strong> key policy component<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> social safety nets pillar, is a prime example <strong>of</strong> this.<br />

2

<strong>Social</strong> Safety Nets<br />

As debates around <strong>the</strong> real ability for economic growth to reduce poverty and <strong>in</strong>equality<br />

cont<strong>in</strong>ue (see Dollar and Kray 2000; and Weisbrot 2000; Oxfam 2000 for debate), it<br />

appears that it has been accepted that economic growth will not <strong>in</strong>stantly ‘trickle down’<br />

to <strong>the</strong> most vulnerable and <strong>the</strong>re is a <strong>the</strong> need for <strong>the</strong> protection <strong>of</strong> vulnerable groups via<br />

social safety nets. The Nicaraguan PRSP states that ‘special protection’ must be afforded<br />

to children under five years <strong>of</strong> age and o<strong>the</strong>r particularly vulnerable groups, such as<br />

‘abused women’, <strong>the</strong> disabled and <strong>the</strong> aged (Gobierno de Nicaragua 2001:34). <strong>Social</strong><br />

protection <strong>in</strong> this context takes <strong>the</strong> form <strong>of</strong> a transfer <strong>of</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ancial and <strong>in</strong> k<strong>in</strong>d resources<br />

(<strong>in</strong> general food or food vouchers) to those selected as especially ‘needy’. The most<br />

fundamental criticism <strong>of</strong> this welfarist approach is that <strong>the</strong> ‘protection’ <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most<br />

vulnerable does noth<strong>in</strong>g to change <strong>the</strong> root causes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir vulnerability.<br />

Emerg<strong>in</strong>g from criticisms <strong>of</strong> def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g poverty as <strong>in</strong>come or consumption, and <strong>in</strong><br />

recognition that <strong>the</strong> relationship between <strong>in</strong>come or consumption level and o<strong>the</strong>r forms<br />

<strong>of</strong> deprivation such as environmental risks, crime, violence, is <strong>of</strong>ten weak, <strong>the</strong> concept <strong>of</strong><br />

vulnerability evolved as one attempt to encompass more subjective elements <strong>of</strong> wellbe<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong>to <strong>of</strong>ficial discourses (see McIlwa<strong>in</strong>e 2002 for fur<strong>the</strong>r discussion). Vulnerability<br />

was considered useful with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> development context as a dynamic concept <strong>in</strong> relation<br />

to <strong>the</strong> concept <strong>of</strong> poverty that is static and describes only <strong>the</strong> situation <strong>of</strong> people at a<br />

particular po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>in</strong> time. Although <strong>the</strong> poor may be vulnerable, and <strong>the</strong> vulnerable poor,<br />

<strong>the</strong> two are dist<strong>in</strong>ct concepts and vulnerability and poverty cannot be used<br />

<strong>in</strong>terchangeably.<br />

The overall focus <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> PRSP is poverty, more explicitly <strong>the</strong> PRSP highlights that ‘top<br />

priority’ has been assigned to <strong>the</strong> reduction <strong>of</strong> extreme poverty. In terms <strong>of</strong> social safety<br />

nets <strong>the</strong> focus is on <strong>the</strong> protection <strong>of</strong> vulnerable groups, however, <strong>the</strong> PRSP also states<br />

that social programs will be crucial for reduc<strong>in</strong>g extreme poverty (Gobierno de Nicaragua<br />

2001:24). This suggests that social programmes are be<strong>in</strong>g used to fulfil more than one<br />

aim, or ra<strong>the</strong>r that <strong>the</strong> real aim is not that which is stated. In <strong>the</strong> short term <strong>the</strong> priority<br />

is <strong>the</strong> reduction <strong>of</strong> extreme poverty <strong>in</strong> l<strong>in</strong>e with <strong>in</strong>ternational development goals.<br />

Resources will be dedicated to mov<strong>in</strong>g those below <strong>the</strong> extreme poverty l<strong>in</strong>e, over this<br />

l<strong>in</strong>e. 3 What this means <strong>in</strong> practice is that while <strong>the</strong> numbers <strong>in</strong> extreme poverty may go<br />

down, <strong>the</strong> numbers <strong>in</strong> poverty will rise, s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong>se resources are not sufficient to move<br />

<strong>the</strong> extreme poor out <strong>of</strong> poverty. Moreover <strong>the</strong> change is not susta<strong>in</strong>able.<br />

The notion <strong>of</strong> vulnerability accepts that people’s situations change and can be changed.<br />

It does not <strong>the</strong>n focus on <strong>the</strong> resources available to different groups <strong>of</strong> people to<br />

describe <strong>the</strong>ir actual position with<strong>in</strong> a society, but to provide <strong>in</strong>sights <strong>in</strong>to how people<br />

may use those resources to change <strong>the</strong>ir situation. This focus is on assets and asset<br />

ownership (Moser, 1996: 24) where assets are def<strong>in</strong>ed as labour, human capital,<br />

productive assets (such as land and hous<strong>in</strong>g), household relations (focus<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>in</strong>come<br />

pool<strong>in</strong>g and consumption shar<strong>in</strong>g), and social capital (referr<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> capacity to make<br />

claims at <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>ter-household level with<strong>in</strong> communities based on social ties). The<br />

dynamic <strong>of</strong> vulnerability rests on <strong>the</strong> strategies adopted by <strong>the</strong> poor to withstand shocks<br />

through diversify<strong>in</strong>g and mobilis<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir asset base (see McIlwa<strong>in</strong>e 2002 for fur<strong>the</strong>r<br />

discussion). Welfare type programmes <strong>of</strong> giv<strong>in</strong>g money or food to those <strong>in</strong> a ‘vulnerable’<br />

3 In Nicaragua <strong>the</strong>1998 poverty l<strong>in</strong>e on which PRSP calculations were based was US$ 402.05 per year. The<br />

extreme poverty l<strong>in</strong>e for 1998 was estimated at US$ 212.22.<br />

3

position does little to alter this asset base or <strong>the</strong> capacity to mobilise it. As such <strong>the</strong>y do<br />

little to reduce vulnerability. They may actually do more harm than good as a gendered<br />

consideration <strong>of</strong> such projects and <strong>the</strong> possible outcomes suggests.<br />

One <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> first problems noted with welfare programmes or <strong>the</strong> provision <strong>of</strong> social<br />

safety nets is <strong>the</strong> unit <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>clusion. Often programmes are <strong>in</strong>tended to improve <strong>the</strong> well<br />

be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ‘family’. This assumes that <strong>the</strong>re is a universally agreed notion <strong>of</strong> what<br />

constitutes a ‘family’. Programmes <strong>of</strong>ten use as a model <strong>the</strong> nuclear family, despite <strong>the</strong><br />

fact that this may not be <strong>the</strong> majority household type. 4 While many different household<br />

forms exist, only female-headed households are generally considered as a specific<br />

alternative household type. Orig<strong>in</strong>ally concern rested on female-headed households as<br />

physical manifestations <strong>of</strong> ‘dysfunctional’ families. More recently <strong>the</strong> ‘fem<strong>in</strong>isation <strong>of</strong><br />

poverty’ <strong>the</strong>sis <strong>in</strong> which female-headed units are presented as <strong>the</strong> ‘poorest <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> poor’<br />

has achieved general acceptance. Although criticised by many gender analysts and<br />

academics (see Chant 2003 for a full discussion), <strong>the</strong> ‘poorest <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> poor’ notion has<br />

been embraced by key <strong>in</strong>ternational actors and policy makers.<br />

The notion <strong>of</strong> women headed households as <strong>the</strong> ‘poorest <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> poor’ is based on an<br />

analysis <strong>of</strong> total household <strong>in</strong>comes, with total household <strong>in</strong>come be<strong>in</strong>g lower than <strong>in</strong><br />

comparable male-headed units, not least s<strong>in</strong>ce women earn less than men. However,<br />

studies suggest women-headed households demonstrate a more equal distribution <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

(limited) <strong>in</strong>come available mak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> actual resources available to women and children<br />

with<strong>in</strong> woman headed households approximately equal to male-headed units (see Chant<br />

1999; Chant 2003 for full discussion). The fact that male heads may withhold <strong>in</strong>come<br />

from <strong>the</strong> household for personal consumption, that is not contribute all that <strong>the</strong>y earn to<br />

<strong>the</strong> common ‘pot’, has been seen to place women and children who depend on that<br />

<strong>in</strong>come <strong>in</strong> a situation <strong>of</strong> so called ‘secondary poverty’ (for evidence from Nicaragua see<br />

Bradshaw 2002a) 5 .<br />

This notion <strong>of</strong> secondary poverty is implicit <strong>in</strong> programmes that target resources dest<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

for <strong>the</strong> family at women. That is <strong>the</strong>re is an acceptance that men may use resources <strong>in</strong><br />

activities that do not necessarily benefit o<strong>the</strong>r household members, or <strong>in</strong>crease overall<br />

well be<strong>in</strong>g. Ra<strong>the</strong>r than tackl<strong>in</strong>g this issue <strong>the</strong> programmes attempt to circumvent <strong>the</strong><br />

‘problem’ by target<strong>in</strong>g resources at women. However, what is assumed is that <strong>the</strong><br />

resources given to women will stay with women, that <strong>the</strong>y have ultimate control over<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir use. There is evidence to suggest that this is not always <strong>the</strong> case (see Dwyer and<br />

Bruce 1988). Even <strong>in</strong> situations where women ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> control over <strong>the</strong>ir own<br />

resources, <strong>the</strong> implications for household well be<strong>in</strong>g are not as clear cut as may be<br />

expected.<br />

Recent research from Nicaragua (Bradshaw 2002a) suggests that <strong>the</strong> ‘extra’ <strong>in</strong>come<br />

earned or received by women <strong>in</strong> male-headed households does not necessarily<br />

complement or add to exist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>come sources. The resources women br<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong><br />

home may be seen by <strong>the</strong> male ‘head’ to substitute for his earn<strong>in</strong>gs, that is he withholds<br />

<strong>the</strong> equivalent <strong>of</strong> his own earn<strong>in</strong>gs leav<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> resources available to o<strong>the</strong>r household<br />

members unchanged. The research also highlighted that women who were <strong>in</strong>come<br />

4 Family is generally used to refer to <strong>the</strong> wider social group<strong>in</strong>g while household more correctly def<strong>in</strong>es a<br />

domestic unit that is usually, but not always, based on k<strong>in</strong>ship ties.<br />

5 Studies suggest that <strong>in</strong> contrast women wage earners are more likely to contribute all <strong>the</strong>ir wages to <strong>the</strong><br />

household. While studies have highlighted this ‘irresponsible’ behaviour <strong>of</strong> men few have problematised<br />

this ‘altruistic’ behaviour <strong>of</strong> women.<br />

4

earners were more likely to perceive <strong>the</strong>mselves as participat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> decision mak<strong>in</strong>g<br />

with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> household. However, <strong>in</strong> turn those women who stated that <strong>the</strong>y participated<br />

<strong>in</strong> decision mak<strong>in</strong>g with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> household were more likely to mention economic issues as<br />

<strong>the</strong> basis for arguments with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> home. This suggests <strong>the</strong>re may be a trade <strong>of</strong>f with any<br />

ga<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong> economic well be<strong>in</strong>g made be<strong>in</strong>g made at <strong>the</strong> expense <strong>of</strong> social well be<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

The real impact <strong>of</strong> channell<strong>in</strong>g resources to <strong>the</strong> household through women is largely<br />

unknown. Some suggest an association between giv<strong>in</strong>g such resources to women and a<br />

rise <strong>in</strong> conflict with<strong>in</strong> households and violence aga<strong>in</strong>st women, however evidence is <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

anecdotal and as such is <strong>of</strong>ten, or easily, ignored. Moreover, as <strong>the</strong> focus on women <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>se social protection programmes derives from efficiency not equity concerns such<br />

negative social impacts are <strong>of</strong> little account to policy makers.<br />

The more efficient use <strong>of</strong> resources, through improved target<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> exist<strong>in</strong>g resources<br />

ra<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>the</strong> provision <strong>of</strong> more resources is fundamental to <strong>the</strong> social safety net<br />

proposed with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> PRSP framework (Gobierno de Nicaragua 2003). The provision <strong>of</strong><br />

welfare for <strong>the</strong> poorest is envisaged to occur not solely nor necessarily through <strong>in</strong>creased<br />

spend<strong>in</strong>g. The importance <strong>of</strong> improved target<strong>in</strong>g is also highlighted as is <strong>the</strong><br />

rationalisation and consolidation <strong>of</strong> exist<strong>in</strong>g programmes and <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>creased role <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

private sector, measures that o<strong>the</strong>rs have suggested will have a negative ra<strong>the</strong>r than<br />

positive affect on <strong>the</strong> poor (see CCER 2001). This will occur alongside <strong>the</strong> privatisation<br />

<strong>of</strong> basic goods and services such as electricity, water and telecommunications <strong>in</strong> l<strong>in</strong>e with<br />

<strong>the</strong> conditionalities <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> IMF’s Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility (PRGF)<br />

agreements The privatisation <strong>of</strong> basic goods and services shifts <strong>the</strong>ir provision from <strong>the</strong><br />

public to <strong>the</strong> private sphere, and as such tends to impact on women <strong>the</strong> most, as<br />

demonstrated <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1980s by Structural Adjustment Programmes (see Elson 1995) .<br />

Background to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Social</strong> <strong>Protection</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

The Red de Protección <strong>Social</strong> (RPS) or <strong>the</strong> <strong>Social</strong> <strong>Protection</strong> <strong>Network</strong> is f<strong>in</strong>anced by two<br />

loans form <strong>the</strong> Inter American Development Bank (BID) <strong>the</strong> first <strong>of</strong> $9 million and <strong>the</strong><br />

second <strong>of</strong> $20 million 6 . The pilot phase <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> implementation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RPS is now<br />

complete and <strong>the</strong> results are considered to be ‘positive’ by its funders. Successful<br />

completion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> goals laid out <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> first phase ‘triggers’ <strong>the</strong> fund<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> second<br />

phase. The impact evaluation <strong>in</strong> fact suggests goals have not only been met, but that<br />

outcomes have been better than expected (BID 2003).<br />

The overall objective <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RPS is to improve <strong>the</strong> well be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> population <strong>in</strong><br />

extreme poverty, support<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> accumulation <strong>of</strong> human capital (BID 2003: 2). This<br />

suggests that a relationship is seen to exist between <strong>in</strong>creased human capital formation<br />

and <strong>in</strong>creased well be<strong>in</strong>g. Stocks <strong>of</strong> Human Capital such as health and education have<br />

been seen to be important <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> improv<strong>in</strong>g access to <strong>in</strong>come generat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

opportunities (<strong>in</strong>come poverty approach) withstand<strong>in</strong>g shocks (vulnerability approach)<br />

and for a dignified life (human development approach). Human capital formation is also<br />

seen as important for improv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> overall productivity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> labour force and<br />

attract<strong>in</strong>g foreign <strong>in</strong>vestors (market oriented approach). The relationship between<br />

human capital and well be<strong>in</strong>g may be limited, may be <strong>in</strong>direct and may be only over <strong>the</strong><br />

long term.<br />

6 Interest payable on <strong>the</strong> loan is 1% dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> first ten years (when repayment is not expected), ris<strong>in</strong>g to<br />

2% from <strong>the</strong>n onwards. The maximum repayment period is 40 years.<br />

5

The documentation also suggests that <strong>the</strong> idea <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RPS is to change <strong>the</strong> behaviour <strong>of</strong><br />

families <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> formation <strong>of</strong> human capital and that <strong>the</strong> programme seeks to<br />

promote a ‘responsible attitude’ among families (BID 2003). Such comments besides<br />

be<strong>in</strong>g highly paternalistic, assume that <strong>the</strong> behaviour <strong>of</strong> families is at present a problem.<br />

That is <strong>the</strong> assumption is that families do not know how to behave properly <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong><br />

reduc<strong>in</strong>g health risks nor do <strong>the</strong>y understand <strong>the</strong> value <strong>of</strong> education. It could be<br />

contended that on <strong>the</strong> contrary education and health are highly prized but barely<br />

reachable goals for families liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> extreme poverty. The focus suggests <strong>the</strong> problem is<br />

<strong>the</strong> ‘bad’ behaviour <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividuals or families, ignor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> structural <strong>in</strong>equalities that<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>e that behaviour and shift<strong>in</strong>g blame from wider society to <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual or <strong>in</strong><br />

effect – blam<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> victim.<br />

A study undertaken <strong>in</strong> July <strong>of</strong> 2001 (Bradshaw 2002 b) showed that <strong>the</strong> great majority <strong>of</strong><br />

women <strong>in</strong>terviewed already shared <strong>the</strong> government’s view <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> importance <strong>of</strong><br />

education for both boys and girls. However, <strong>the</strong> reasons for valu<strong>in</strong>g education are not as<br />

straightforward as may be assumed and not necessarily those <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> government. The<br />

recent national development plan (Gobierno de Nicaragua 2003: 15) clearly states that<br />

<strong>the</strong> government is <strong>in</strong>vest<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> human capital to “<strong>in</strong>crease <strong>the</strong> productivity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> workers<br />

and <strong>the</strong>ir work”. In comparison, only a small proportion <strong>of</strong> women <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> study gave<br />

future employment benefits as <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> value perta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g to education. In fact education<br />

was valued not for what it could br<strong>in</strong>g, but ra<strong>the</strong>r what it was thought to stop, most<br />

specifically ‘del<strong>in</strong>quency’ <strong>in</strong> young men (52% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> women <strong>in</strong>terviewed responded <strong>in</strong><br />

this form). In terms <strong>of</strong> young women education was also seen as important <strong>in</strong> order that<br />

<strong>the</strong>y could ‘look after <strong>the</strong>mselves’ <strong>in</strong> later life and not be ‘taken <strong>in</strong>’ or ‘fooled’ by o<strong>the</strong>rs,<br />

most notably men. These notions have both economic and social elements as <strong>the</strong><br />

follow<strong>in</strong>g quotes demonstrate: “Women should learn to wash, to cook and to read so<br />

that <strong>the</strong>y don’t get fooled” or more explicitly “When you know how to read and write<br />

you learn how to work and <strong>the</strong>y can’t fool you”.<br />

It would seem that education is highly valued by <strong>the</strong> poor, but that <strong>the</strong> benefits are<br />

conceptualised <strong>in</strong> social ra<strong>the</strong>r than economic terms. In fact <strong>in</strong> economic terms<br />

education may be seen to br<strong>in</strong>g costs ra<strong>the</strong>r than benefits. In <strong>the</strong> short run <strong>the</strong> costs<br />

<strong>in</strong>clude books, uniforms and <strong>the</strong> opportunity cost <strong>of</strong> lost <strong>in</strong>come for those children<br />

<strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>come generat<strong>in</strong>g activities. In <strong>the</strong> short run <strong>in</strong>vestment <strong>in</strong> human capital<br />

may be associated with reductions <strong>in</strong> well-be<strong>in</strong>g. <strong>Analysis</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> factors that <strong>in</strong>fluence<br />

perceptions <strong>of</strong> decl<strong>in</strong>es and improvements <strong>in</strong> well be<strong>in</strong>g based on <strong>the</strong> data collected via<br />

<strong>the</strong> civil society <strong>Social</strong> Audit <strong>in</strong>itiative (see L<strong>in</strong>neker 2002) suggests that if a poor<br />

household has a child <strong>in</strong> school, irrespective <strong>of</strong> household type, <strong>the</strong>y were more likely to<br />

feel worse <strong>of</strong>f and experience decl<strong>in</strong>es <strong>in</strong> well-be<strong>in</strong>g than households without a child <strong>in</strong><br />

school.<br />

What <strong>the</strong> RPS actually proposes is us<strong>in</strong>g ‘well be<strong>in</strong>g’ <strong>in</strong>centives to ensure human capital<br />

form<strong>in</strong>g behaviour. To benefit f<strong>in</strong>ancially families have to commit to send<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

children to school and to health centres to receive basic health care services such as<br />

vacc<strong>in</strong>ations. They also have to commit to improv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir nutritional state and<br />

attendance at a series <strong>of</strong> educational sessions about health (6 per year) that provide<br />

tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g on reproductive and sexual health, nutrition, <strong>in</strong> ‘environmental health’ and family<br />

hygiene, and <strong>in</strong> child care and breast feed<strong>in</strong>g. If <strong>the</strong>y do not fulfil <strong>the</strong>se obligations <strong>the</strong>n<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir benefits are temporarily withdrawn or may be cancelled. In return a family may<br />

receive one or more <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>centives <strong>of</strong>fered, that <strong>in</strong>clude a school pack (worth $20 per<br />

6

child) for all eligible children <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> first to <strong>the</strong> fourth grade, and a grant ($90 per family).<br />

In terms <strong>of</strong> health <strong>the</strong> benefits are a food grant ($207 per family) and an additional grant<br />

worth $130 per family for th<strong>in</strong>gs such as vacc<strong>in</strong>ations and vitam<strong>in</strong> supplements.<br />

It is <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g to note that recent research (L<strong>in</strong>neker 2002) highlights that whom<br />

women and men receive resources from, <strong>in</strong>formal or formal agencies and private and<br />

public sources, is important <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> perceptions <strong>of</strong> well be<strong>in</strong>g deriv<strong>in</strong>g from <strong>the</strong>se<br />

resources. Importantly this research also suggests that <strong>the</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> central<br />

government work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a community may, perversely, be more closely related to feel<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

<strong>of</strong> a decl<strong>in</strong>e ra<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> women’s well be<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Mo<strong>the</strong>rs have been targeted by <strong>the</strong> Government as <strong>the</strong> receivers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> resources,<br />

“motivated by <strong>the</strong> evidence that resources controlled by women translate <strong>in</strong>to greater<br />

improvements <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> well be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> children and <strong>the</strong> family” (BID 2003: 2 author’s<br />

translation). In order to receive <strong>the</strong> resources children are obliged to attend school and<br />

health cl<strong>in</strong>ics and <strong>the</strong>ir mo<strong>the</strong>rs are obliged to ensure that <strong>the</strong>y do so. Not only that but<br />

women are also obliged to undergo ‘school<strong>in</strong>g’ <strong>the</strong>mselves. This not only places an<br />

added burden on women, but also re<strong>in</strong>forces stereotypical ideas <strong>of</strong> women’s roles and<br />

responsibilities. In addition <strong>the</strong> fact that women have to attend courses or risk <strong>the</strong> loss<br />

<strong>of</strong> resources assumes that women are available or that <strong>the</strong>ir work responsibilities allow<br />

this. Better stated, <strong>the</strong> underly<strong>in</strong>g assumption is that women are not <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>come<br />

generat<strong>in</strong>g activities. While it is notoriously difficult to obta<strong>in</strong> reliable data concern<strong>in</strong>g<br />

women’s employment national level studies <strong>in</strong> Nicaragua suggest many women work.<br />

Recent research (Bradshaw 2002b) also highlights <strong>the</strong> importance <strong>of</strong> women’s work to<br />

household survival, and <strong>in</strong> those households with only one worker, <strong>in</strong> 32% <strong>of</strong> cases this<br />

worker is a woman.<br />

Despite this <strong>the</strong> notion <strong>of</strong> women’s primary role as be<strong>in</strong>g mo<strong>the</strong>rs ra<strong>the</strong>r than ‘workers’<br />

is re<strong>in</strong>forced with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> RPS documentation as it suggests <strong>the</strong> RPS seeks to promote <strong>the</strong><br />

‘development’ <strong>of</strong> women to support actions that consolidate <strong>the</strong> family unit and that<br />

women beneficiaries will directly benefit through widen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir knowledge and abilities<br />

<strong>in</strong> order that <strong>the</strong>y can participate actively <strong>in</strong> improv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> health and nutrition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

families and <strong>the</strong> basic education <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir children. The RPS is a good example <strong>of</strong> how<br />

policies that <strong>in</strong>clude or target women can be as, if not more, damag<strong>in</strong>g than those that<br />

exclude or ignore women.<br />

For some women <strong>the</strong> burden <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RPS will be even greater s<strong>in</strong>ce women are to be <strong>the</strong><br />

community promoters <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> programme. Those who act as promoters will be<br />

beneficiaries that ‘voluntarily’ wish to collaborate <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> programme. This be<strong>in</strong>g said <strong>the</strong><br />

documentation also notes <strong>the</strong>y will be ‘designated’ by <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r beneficiaries with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

programme. This suggests ei<strong>the</strong>r that promoters may have little choice over <strong>the</strong> matter,<br />

be<strong>in</strong>g designated by o<strong>the</strong>rs and not feel<strong>in</strong>g able to decl<strong>in</strong>e, or that <strong>the</strong>re will be little<br />

choice as <strong>the</strong> usual leaders step forward to assume <strong>the</strong> role. As <strong>the</strong>re is no mention <strong>of</strong><br />

what <strong>the</strong> advantages <strong>of</strong> such a position are, it is not easy to predict which would be <strong>the</strong><br />

case. In ei<strong>the</strong>r scenario, however, an outcome may be conflict with<strong>in</strong> a community and<br />

ill feel<strong>in</strong>g between women.<br />

Phase I implementation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Social</strong> <strong>Protection</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

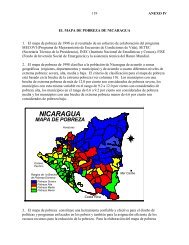

The beneficiaries <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> first phase <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RPS were determ<strong>in</strong>ed on <strong>the</strong> basis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

government’s poverty map. However, it was decided that a f<strong>in</strong>er selection <strong>in</strong>strument<br />

7

was need and an ‘ad hoc’ <strong>in</strong>strument was developed (BID 2003: 9) that <strong>in</strong>cluded four<br />

elements: family size, access to potable water; access to latr<strong>in</strong>es; level <strong>of</strong> illiteracy.<br />

Fur<strong>the</strong>r selection criteria <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>the</strong> organisational capacity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> communities. The<br />

evaluation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RPS suggests that 80% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> families selected live <strong>in</strong> extreme poverty.<br />

Nationally <strong>the</strong> total number <strong>of</strong> people liv<strong>in</strong>g below <strong>the</strong> poverty l<strong>in</strong>e was estimated to be<br />

2,206,742 <strong>in</strong> 1998, which represents 51% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> population. The number <strong>of</strong> people<br />

liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> extreme poverty <strong>in</strong> 1998 is estimated to be 891,720 represent<strong>in</strong>g 40.4% <strong>of</strong> all<br />

poor and 20.7% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> population. Ultimately phase I <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RPS only benefited 10,093<br />

families, <strong>in</strong> six municipalities, <strong>in</strong> only two departments <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> country (Madriz and<br />

Matagalpa). That is <strong>the</strong> first phase <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RPS reached less than 1% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> extreme poor,<br />

and not even 0.5% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> poor. Although <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> beneficiaries will be more than<br />

doubled (a fur<strong>the</strong>r 12,500 new households) dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> second phase <strong>of</strong> implementation,<br />

even with better target<strong>in</strong>g as a proportion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> numbers <strong>in</strong> extreme poverty <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

country <strong>the</strong> RPS has very little impact (a maximum 2.5% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> extreme poor will<br />

benefit).<br />

In its first or pilot phase <strong>of</strong> implementation <strong>the</strong> RPS had a number <strong>of</strong> objectives that<br />

<strong>in</strong>cluded those that were aimed at sett<strong>in</strong>g up, test<strong>in</strong>g and streng<strong>the</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> system before<br />

full implementation <strong>in</strong> phase II. Meet<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> goals set for improvements <strong>in</strong> health,<br />

education and nutrition would ‘trigger’ release <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> full funds for phase II. The<br />

objectives <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> first phase are summarised as: 7<br />

a) To establish <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>itial operative framework <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RPS<br />

b) To supplement <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>comes <strong>of</strong> families <strong>in</strong> extreme poverty for up to three years to<br />

<strong>in</strong>crease <strong>the</strong>ir expenditure on food<br />

c) Increase <strong>the</strong> ‘care’ <strong>of</strong> children under <strong>the</strong> age <strong>of</strong> five<br />

d) Reduce school drop out rates dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> first four years <strong>of</strong> school<strong>in</strong>g<br />

The improvement <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> ‘care’ <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> under fives appears to have to <strong>in</strong>terrelated strands.<br />

First, a programme <strong>of</strong> vacc<strong>in</strong>ations and second an improvement <strong>in</strong> ‘nutritional care’. The<br />

expression ‘nutritional care’ suggests that <strong>the</strong> aim is to do more than <strong>in</strong>crease food<br />

consumption but also to change behaviour presumably via <strong>the</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g programmes<br />

mentioned above. One important aspect <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> health related activities <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RPS is that<br />

private providers were contracted to implement <strong>the</strong> programmes dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> first phase<br />

and <strong>the</strong>ir performance was also evaluated <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> this cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> phase II.<br />

In terms <strong>of</strong> education <strong>the</strong> focus is on <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>corporation <strong>of</strong> children <strong>in</strong>to schools and <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

cont<strong>in</strong>uation <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> school system. It is <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g that although primary education<br />

consists <strong>of</strong> 6 grades, <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>centives are only <strong>of</strong>fered to children <strong>in</strong> grades 1 to 4.<br />

Although <strong>the</strong> aim <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> project was to <strong>in</strong>crease enrolment by 5%, retention <strong>of</strong> exist<strong>in</strong>g<br />

students was as, if not more, important and <strong>the</strong> goal <strong>in</strong> this case was to improve by more<br />

than 10% retention rates.<br />

As can be seen, <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> focus <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RPS is young children. As such <strong>the</strong> RPS fulfils at<br />

least <strong>in</strong> part commitments made by <strong>the</strong> government under <strong>the</strong> PRSP agreements. The<br />

f<strong>in</strong>al PRSP - <strong>the</strong> Streng<strong>the</strong>ned Strategy for Economic Growth and Poverty Reduction<br />

(ERCERP) highlights <strong>the</strong> need for ‘special protection’ to be afforded to children under<br />

five years <strong>of</strong> age (Gobierno de Nicaragua 2001:34). However, it also notes <strong>the</strong> existence<br />

7 From: Red de Protección <strong>Social</strong> (NI-0075), Resumen Ejecutivo (author’s translation)<br />

8

and need <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r particularly vulnerable groups, such as ‘abused women’ <strong>the</strong> disabled<br />

and <strong>the</strong> aged. 8 The RPS makes no mention <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se groups.<br />

The elements <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> Phase I <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RPS are very much l<strong>in</strong>ked to achiev<strong>in</strong>g not only<br />

<strong>the</strong> PRSP goals but perhaps more importantly those <strong>in</strong> l<strong>in</strong>e with <strong>the</strong> Millennium<br />

Development Goals (see Kabeer 2003 for discussion). These <strong>in</strong>clude cutt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> halve by<br />

2015 <strong>the</strong> proportion <strong>of</strong> people whose <strong>in</strong>come is less than <strong>the</strong> extreme poverty l<strong>in</strong>e. It also<br />

<strong>in</strong>cludes goals related to <strong>in</strong>creased access to primary education and reductions <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>fant<br />

and under 5 mortality rates. It is not surpris<strong>in</strong>g given <strong>the</strong> similarities between <strong>the</strong>se goals<br />

and <strong>the</strong> policies outl<strong>in</strong>ed that recent World Bank (2003) estimations suggest that it is<br />

possible that <strong>the</strong>se goals will be met. However, achiev<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r Millennium<br />

Development Goals is less likely. That is while <strong>in</strong>fant and under 5 mortality rates may be<br />

cut <strong>the</strong> proposed reduction <strong>in</strong> levels <strong>of</strong> chronic malnutrition is deemed ‘unlikely’ by <strong>the</strong><br />

World Bank. Similarly, while access to primary education will be <strong>in</strong>creased, it is deemed<br />

‘very unlikely’ that <strong>the</strong> general reduction <strong>in</strong> illiteracy rates will be achieved.<br />

Tak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to account <strong>the</strong> wider poverty context <strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong> RPS is be<strong>in</strong>g implemented,<br />

and <strong>the</strong> multidimensionality <strong>of</strong> poverty, <strong>the</strong> RPS appears not only narrow <strong>in</strong> its<br />

implementation, but also narrow <strong>in</strong> its orientation.<br />

Evaluation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Outcomes <strong>of</strong> Phase I <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Social</strong> <strong>Protection</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

An evaluation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> first phase <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RPS has led <strong>the</strong> funders, <strong>the</strong> Inter American<br />

Development Bank, to suggest that <strong>the</strong> results <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> programme to have been positive<br />

<strong>in</strong> that all goals were met or surpassed. Although <strong>the</strong> results presented do <strong>in</strong>deed seem<br />

to suggest that <strong>the</strong> RPS has been a success, <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> its own measures <strong>of</strong> success, it is<br />

important to critically exam<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> results. Perhaps more importantly <strong>the</strong> effect <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

RPS needs to be evaluated <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> wider impact, not just <strong>the</strong> narrow goals suggested<br />

as <strong>in</strong>dicators <strong>of</strong> its success by its authors.<br />

In terms <strong>of</strong> education as noted above <strong>the</strong> goal was to <strong>in</strong>crease matriculation by 5% and<br />

retention by 10%. Both targets have been met and <strong>the</strong> data suggests no differences <strong>in</strong><br />

terms <strong>of</strong> matriculation and retention by gender. However, differences exist <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RPS on matriculation and retention. While <strong>the</strong> former had <strong>the</strong> lower<br />

target (5% <strong>in</strong>crease) matriculation <strong>in</strong>creased by 21.7%, this compared to retention that<br />

did not manage to comply with its target <strong>of</strong> a greater than 10% <strong>in</strong>crease achiev<strong>in</strong>g only<br />

9% <strong>in</strong>crease overall and 10% among <strong>the</strong> extreme poor. 9 The reasons for this discrepancy<br />

have not been fully explored. The results could suggest that parents were enroll<strong>in</strong>g<br />

children <strong>in</strong> school to receive <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>itial benefits, both f<strong>in</strong>ancial and educational, but<br />

f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g retention difficult, despite <strong>the</strong>se <strong>in</strong>centives. Alternatively <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> children<br />

<strong>of</strong> school age who have never been enrolled <strong>in</strong> school may have been greatly<br />

underestimated <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> past, for various reasons.<br />

Ultimately demand outstripped supply as no provision had been made to contract extra<br />

teachers to cover <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>creased enrolment, nor a sufficient budget provided. Although<br />

this has been presented as highlight<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> overwhelm<strong>in</strong>g success <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>itiative, looked<br />

at from ano<strong>the</strong>r view po<strong>in</strong>t it suggests <strong>the</strong> standard <strong>of</strong> school<strong>in</strong>g received by children is<br />

8 Although not noted as a particularly vulnerable group, <strong>the</strong> matrix <strong>of</strong> policy actions <strong>in</strong>cludes a programme<br />

to ‘fight women’s poverty’ via credit schemes and <strong>the</strong> garden economy (Gobierno de Nicaragua 2001:131).<br />

9 Compared to <strong>the</strong> control group – data presented <strong>in</strong> BID 2003 Table 1.2<br />

9

<strong>of</strong> little importance to those implement<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> project. What is key is gett<strong>in</strong>g children<br />

<strong>in</strong>to school, <strong>the</strong> education <strong>the</strong>y receive <strong>the</strong>re appears to be <strong>of</strong> less, or little concern.<br />

In terms <strong>of</strong> health aga<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> impact evaluation suggests targets were met or surpassed.<br />

However, once aga<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> targets <strong>the</strong>mselves can be questioned. Results <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

programme <strong>of</strong> ‘vigilance’ and promotion <strong>of</strong> growth and development (VPCD), that<br />

<strong>in</strong>cluded elements such as monitor<strong>in</strong>g weight ga<strong>in</strong> among babies under 3 years old, were<br />

said to have been 2 or 3 times better than <strong>the</strong> targets. It is important to remember that<br />

health services were contracted out to private providers and <strong>the</strong>y were paid by coverage<br />

and outcome (eg weight ga<strong>in</strong>). As <strong>the</strong> evaluation itself notes this suggests a conflict <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>terest.<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r element monitored under <strong>the</strong> VPCD was proportion <strong>of</strong> children under 3 years<br />

<strong>of</strong> age who had been given an iron supplement to reduce iron deficiency. While anaemia<br />

is a serious problem <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> country, iron supplements would not be necessary if a healthy<br />

diet was available to children or maternal health was improved. The goal provides a clear<br />

example <strong>of</strong> focuss<strong>in</strong>g on symptoms not causes <strong>of</strong> poor health, look<strong>in</strong>g for a quick fix<br />

ra<strong>the</strong>r than address<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> fundamental problem.<br />

The second health element be<strong>in</strong>g monitored focussed on <strong>the</strong> vacc<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> children<br />

between <strong>the</strong> ages <strong>of</strong> 1 and 2 years old which showed a net ga<strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong> 17.3% (compared to a<br />

target <strong>of</strong> 10%) after hav<strong>in</strong>g taken account <strong>of</strong> a general <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> vacc<strong>in</strong>ation coverage<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> period <strong>in</strong> non RPS areas. What both <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> enrolment <strong>in</strong> schools and<br />

<strong>the</strong> take up vacc<strong>in</strong>ations suggests is, as noted above, <strong>the</strong> orig<strong>in</strong>al notion underp<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong><br />

RPS <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> need to change <strong>the</strong> behaviour <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> poor was erroneous. School<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

health appear to be valued by <strong>the</strong> poor as much as any o<strong>the</strong>r group <strong>in</strong> society what has<br />

been lack<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> past was not lack <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terest, but lack <strong>of</strong> access.<br />

The f<strong>in</strong>al element considered <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> evaluation <strong>of</strong> phase I <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RPS was focussed on<br />

consumption <strong>of</strong> food as a proportion <strong>of</strong> total consumption <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> family. The goal was<br />

<strong>the</strong> only one that was not to be measured by a percentage change, but ra<strong>the</strong>r stated as<br />

‘observe <strong>the</strong> tendency <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> change’. Despite <strong>the</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> precision <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> goal set, it is<br />

said to have been ‘achieved’ (see BID 2003 table 1.2). Although no explanation <strong>of</strong> how<br />

this goal was achieved, or what this means is given, some figures related to food<br />

expenditure are presented. The average ‘net impact’ <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> programme <strong>in</strong> annual per<br />

capita expenditure is said to have been 25%, and <strong>of</strong> this 88% was spent on food - or <strong>the</strong><br />

equivalent <strong>of</strong> an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> US$64 per capita food expenditure (BID 2003: 7).<br />

These figures are difficult to <strong>in</strong>terpret. S<strong>in</strong>ce measur<strong>in</strong>g changes <strong>in</strong> food consumption<br />

would mean longitud<strong>in</strong>al household research it is perhaps safe to assume <strong>the</strong>y refer to<br />

expenditure with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> RPS on food related programmes, ra<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>the</strong> expenditure by<br />

households on food. If this is <strong>the</strong> case, <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>clusion here suggests that it is be<strong>in</strong>g<br />

assumed that <strong>the</strong> resources given as part <strong>of</strong> programmes such as <strong>the</strong> RPS are used for <strong>the</strong><br />

purposes <strong>in</strong>tended. This is a problematic assumption.<br />

Even when resources are given <strong>in</strong> k<strong>in</strong>d ra<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>in</strong> cash, <strong>the</strong>y are not always used for<br />

<strong>the</strong> purposes <strong>in</strong>tended by <strong>the</strong> donors. While it is usually assumed that this is due to men<br />

ga<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g control <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> resources and us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>m for personal consumption it is important<br />

to note that this is also not always <strong>the</strong> case. In fact resources may be ‘misused’ for good<br />

reason, <strong>in</strong> that <strong>the</strong> household may have different needs or prioritise <strong>the</strong>ir needs<br />

differently than policy makers. It is rational, for example, that <strong>the</strong> illness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> key wage<br />

10

earner take priority and resources be diverted <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> short term to improve his or her<br />

health and thus well be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> medium to long term.<br />

What narrow programmes such as <strong>the</strong> RPS do not take <strong>in</strong>to account is not only that <strong>the</strong><br />

well be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> an <strong>in</strong>dividual is multi-dimensional, but that one <strong>in</strong>dividual’s well be<strong>in</strong>g may<br />

be related to that <strong>of</strong> ano<strong>the</strong>r person – <strong>in</strong> particular that <strong>the</strong> health and well be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong><br />

children may be <strong>in</strong>tegrally l<strong>in</strong>ked to that <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir parents.<br />

The evaluation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RPS focuses only on <strong>the</strong> ‘beneficiaries’ <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> project and does not<br />

consider <strong>the</strong> wider impact <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> programmes on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r actors <strong>in</strong>volved. Most<br />

notably mo<strong>the</strong>rs are impacted by <strong>the</strong> RPS <strong>in</strong> a number <strong>of</strong> ways. First <strong>the</strong>y are <strong>the</strong><br />

‘receivers’ <strong>of</strong> resources and responsible for <strong>the</strong>ir management and distribution. Second,<br />

<strong>the</strong>y are assumed to be responsible for ensur<strong>in</strong>g children’s attendance at school, for<br />

ensur<strong>in</strong>g children attend health cl<strong>in</strong>ics, and for ensur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> improved ‘nutritional care’ <strong>of</strong><br />

children which may <strong>in</strong> part <strong>in</strong>clude ensur<strong>in</strong>g resources are used to this end. They are also<br />

those who must attend workshops and educational talks throughout <strong>the</strong> year <strong>in</strong> order to<br />

receive f<strong>in</strong>ancial assistance. It is not clear what women ga<strong>in</strong> personally <strong>in</strong> return.<br />

The success <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RPS depends on women assum<strong>in</strong>g an extra burden <strong>of</strong> work, however,<br />

<strong>the</strong> evaluation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RPS does not consider <strong>the</strong> impact on women suggest<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong><br />

policies are assumed to have no impact on women or that <strong>the</strong> impact is positive.<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>terpretation is that any actions that improve <strong>the</strong> well be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> children are not<br />

seen to be a ‘burden’ for women, and that any ‘costs’ <strong>the</strong>y bear are part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mo<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>g<br />

role, re<strong>in</strong>forc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> ideal <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> self-sacrific<strong>in</strong>g mo<strong>the</strong>r. However, some women may<br />

not be able to assume this extra burden, <strong>in</strong> particular women <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>come<br />

generat<strong>in</strong>g activities may f<strong>in</strong>d it difficult not only to attend workshops but also to take<br />

children to <strong>the</strong> health cl<strong>in</strong>ic as this would cut <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong>ir work<strong>in</strong>g day. Compliance may<br />

mean a loss <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>come. However, non-compliance may mean a loss <strong>of</strong> respect <strong>in</strong> that<br />

women who are not able, or not prepared, to assume <strong>the</strong>se responsibilities may be seen<br />

to be ‘bad’ mo<strong>the</strong>rs who do not love <strong>the</strong>ir children. Moreover non-compliance would<br />

mean a loss, not only <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ancial <strong>in</strong>centives but also <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> opportunity for a child or<br />

children to receive school<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Women may suffer personal economic costs through <strong>in</strong>clusion <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> RPS and <strong>the</strong>se are<br />

<strong>in</strong>curred not only <strong>in</strong> order to accrue economic and social benefits for <strong>the</strong>ir children but<br />

also to reduce personal social costs that non-compliance with <strong>the</strong> RPS conditions may<br />

br<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Implications for Phase II<br />

Phase II <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RPS will cover 12,500 new households alongside <strong>the</strong> 10,000 that are<br />

already beneficiaries <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> programme. Selection <strong>of</strong> households will once aga<strong>in</strong> be<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>ed not only on levels <strong>of</strong> poverty but o<strong>the</strong>r criteria, <strong>the</strong> first screen<strong>in</strong>g after<br />

poverty be<strong>in</strong>g dependent on relative education and health <strong>in</strong>dicators and <strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>al<br />

selection between areas be<strong>in</strong>g based on <strong>the</strong>ir relative ‘productive potential’.<br />

A number <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r changes have also been suggested for phase II. The more positive <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> proposals suggest a broaden<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> aspects covered, to <strong>in</strong>clude prenatal care and<br />

attention, for example, and attention to adolescents. Topics for tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g sessions will also<br />

be broadened to <strong>in</strong>clude topics such as <strong>the</strong> patio economy. However, <strong>the</strong> perceived<br />

success <strong>of</strong> implementation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RPS dur<strong>in</strong>g phase I appears to have had one very<br />

11

important potentially negative consequence. The results suggest that targets could be<br />

reached <strong>in</strong> a more ‘cost effective’ manner, that is that <strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ancial <strong>in</strong>centives <strong>of</strong>fered to<br />

improve take up <strong>of</strong> education and health services dur<strong>in</strong>g phase II could be less than<br />

those <strong>of</strong>fered dur<strong>in</strong>g phase I (see BID 2003 for discussion).<br />

In particular <strong>the</strong> high up take <strong>of</strong> vacc<strong>in</strong>ation programmes has led BID to conclude that<br />

<strong>the</strong> food grant <strong>of</strong>fered as an <strong>in</strong>centive <strong>in</strong> this case, can be cut and <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> second phase <strong>the</strong><br />

amount <strong>of</strong>fered will be reduced each year. Similarly dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> next three-year phase it is<br />

<strong>in</strong>tended to gradually cut back <strong>the</strong> amounts <strong>of</strong>fered to some participat<strong>in</strong>g families to<br />

evaluate <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> such measures <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> behaviour change. That is <strong>the</strong> extreme<br />

poor are to be used as ‘gu<strong>in</strong>ea pigs’ to explore how few resources can be <strong>of</strong>fered for <strong>the</strong><br />

same ga<strong>in</strong>s.<br />

The <strong>in</strong>dicators used to evaluate <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> first phase <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RPS will be<br />

supplemented by o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>dicators <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> second phase, most notably <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>clusion <strong>of</strong><br />

‘well be<strong>in</strong>g’ <strong>in</strong>dicators <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g: employment and <strong>in</strong>come sources, possession <strong>of</strong><br />

productive assets and variations <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> price <strong>of</strong> basic products. However as to how <strong>the</strong><br />

RPS is to have a direct, or even <strong>in</strong>direct impact on <strong>the</strong>se elements over <strong>the</strong> three years <strong>of</strong><br />

implementation is far from clear.<br />

An evaluation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> RPS on those on whom its success depends- women<br />

- is not contemplated.<br />

Conclusions<br />

The RPS can be critiqued from a number <strong>of</strong> positions. Most fundamentally, <strong>the</strong><br />

provision <strong>of</strong> food, money and o<strong>the</strong>r services to <strong>the</strong> most vulnerable does not tackle <strong>the</strong><br />

causes <strong>of</strong> that vulnerability and any change that is brought about is unsusta<strong>in</strong>able. It is<br />

also a relative exercise <strong>in</strong> that <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> annual <strong>in</strong>come for those families <strong>in</strong><br />

extreme poverty <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> RPS will only be sufficient to move <strong>the</strong>m over <strong>the</strong><br />

extreme poverty l<strong>in</strong>e and <strong>in</strong>to general poverty.<br />

Tak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to account <strong>the</strong> wider poverty context <strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong> RPS is be<strong>in</strong>g implemented,<br />

and <strong>the</strong> multidimensionality <strong>of</strong> poverty, <strong>the</strong> RPS appears not only narrow <strong>in</strong> its<br />

implementation, but also narrow <strong>in</strong> its orientation. Only a small proportion <strong>of</strong> those<br />

liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> extreme poverty will benefit from <strong>the</strong> programme and with<strong>in</strong> this group<br />

children under five years <strong>of</strong> age are prioritised. While <strong>the</strong> PRSP highlights <strong>the</strong> need for<br />

‘special protection’ to be afforded to children under five years <strong>of</strong> age, it also notes <strong>the</strong><br />

existence and need <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r particularly vulnerable groups, such as ‘abused women’ <strong>the</strong><br />

disabled and <strong>the</strong> aged. The RPS makes no mention <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se groups.<br />

More generally what narrow programmes such as <strong>the</strong> RPS do not take <strong>in</strong>to account is not<br />

only that <strong>the</strong> well be<strong>in</strong>g on an <strong>in</strong>dividual is multi-dimensional, but that one <strong>in</strong>dividual’s<br />

well be<strong>in</strong>g may be related to that <strong>of</strong> ano<strong>the</strong>r person – <strong>in</strong> particular that <strong>the</strong> health and<br />

well be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> children may be <strong>in</strong>tegrally l<strong>in</strong>ked to that <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir parents.<br />

This be<strong>in</strong>g said, <strong>the</strong> RPS is a good example <strong>of</strong> how <strong>in</strong>clusion can be as problematic as<br />

exclusion. Women are targeted with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> RPS as <strong>the</strong> means by which resources will be<br />

delivered to children. Not only does <strong>the</strong> RPS re<strong>in</strong>force exist<strong>in</strong>g gender stereotypes but it<br />

also imposes costs on women that have not been recognised nor <strong>in</strong>cluded when<br />

12

evaluat<strong>in</strong>g its impact. These hidden costs may mean that women’s well be<strong>in</strong>g, economic<br />

and social, may actually decl<strong>in</strong>e as <strong>the</strong> well be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> ‘<strong>the</strong> family’ is improved.<br />

13

References<br />

Bamberger, M. Blackden, M. Fort, L. Manoukian, V. (2001) Gender PRSP source book<br />

chapter draft for comments April 2001.<br />

http://www.worldbank.org/poverty/strategies/chapters/ accessed 16/11/02<br />

BID (2003) La Red de Protección <strong>Social</strong>, Fase II: Informe de Evaluacion<br />

Bradshaw, S. (2002a) <strong>Gendered</strong> Poverties and Power Relations: Look<strong>in</strong>g Inside Communities and<br />

Households <strong>in</strong> Nicaragua CIIR, Puntos de Encuentro, Embajada de Holanda, Nicaragua<br />

Bradshaw, S. (2002b) ‘La pobreza: Una experiencia que se vive de manera dist<strong>in</strong>ta según<br />

el género’ Unpublished research report, August 2002<br />