Nurse Reporter Spring 2009 - Wyoming State Board of Nursing

Nurse Reporter Spring 2009 - Wyoming State Board of Nursing

Nurse Reporter Spring 2009 - Wyoming State Board of Nursing

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

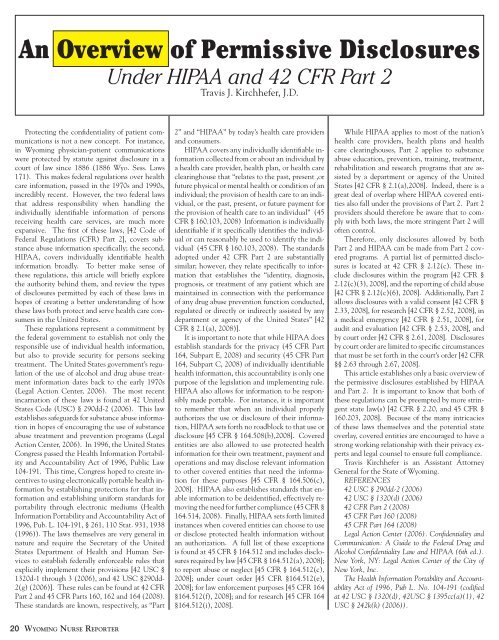

An Overview <strong>of</strong> Permissive Disclosures<br />

Under HIPAA and 42 CFR Part 2<br />

Travis J. Kirchhefer, J.D.<br />

Protecting the confidentiality <strong>of</strong> patient communications<br />

is not a new concept. For instance,<br />

in <strong>Wyoming</strong> physician-patient communications<br />

were protected by statute against disclosure in a<br />

court <strong>of</strong> law since 1886 (1886 Wyo. Sess. Laws<br />

171). This makes federal regulations over health<br />

care information, passed in the 1970s and 1990s,<br />

incredibly recent. However, the two federal laws<br />

that address responsibility when handling the<br />

individually identifiable information <strong>of</strong> persons<br />

receiving health care services, are much more<br />

expansive. The first <strong>of</strong> these laws, [42 Code <strong>of</strong><br />

Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 2], covers substance<br />

abuse information specifically; the second,<br />

HIPAA, covers individually identifiable health<br />

information broadly. To better make sense <strong>of</strong><br />

these regulations, this article will briefly explore<br />

the authority behind them, and review the types<br />

<strong>of</strong> disclosures permitted by each <strong>of</strong> these laws in<br />

hopes <strong>of</strong> creating a better understanding <strong>of</strong> how<br />

these laws both protect and serve health care consumers<br />

in the United <strong>State</strong>s.<br />

These regulations represent a commitment by<br />

the federal government to establish not only the<br />

responsible use <strong>of</strong> individual health information,<br />

but also to provide security for persons seeking<br />

treatment. The United <strong>State</strong>s government’s regulation<br />

<strong>of</strong> the use <strong>of</strong> alcohol and drug abuse treatment<br />

information dates back to the early 1970s<br />

(Legal Action Center, 2006). The most recent<br />

incarnation <strong>of</strong> these laws is found at 42 United<br />

<strong>State</strong>s Code (USC) § 290dd-2 (2006). This law<br />

establishes safeguards for substance abuse information<br />

in hopes <strong>of</strong> encouraging the use <strong>of</strong> substance<br />

abuse treatment and prevention programs (Legal<br />

Action Center, 2006). In 1996, the United <strong>State</strong>s<br />

Congress passed the Health Information Portability<br />

and Accountability Act <strong>of</strong> 1996, Public Law<br />

104-191. This time, Congress hoped to create incentives<br />

to using electronically portable health information<br />

by establishing protections for that information<br />

and establishing uniform standards for<br />

portability through electronic mediums (Health<br />

Information Portability and Accountability Act <strong>of</strong><br />

1996, Pub. L. 104-191, § 261, 110 Stat. 931, 1938<br />

(1996)). The laws themselves are very general in<br />

nature and require the Secretary <strong>of</strong> the United<br />

<strong>State</strong>s Department <strong>of</strong> Health and Human Services<br />

to establish federally enforceable rules that<br />

explicitly implement their provisions [42 USC §<br />

1320d-1 through 3 (2006), and 42 USC §290dd-<br />

2(g) (2006)]. These rules can be found at 42 CFR<br />

Part 2 and 45 CFR Parts 160, 162 and 164 (2008).<br />

These standards are known, respectively, as “Part<br />

2” and “HIPAA” by today’s health care providers<br />

and consumers.<br />

HIPAA covers any individually identifiable information<br />

collected from or about an individual by<br />

a health care provider, health plan, or health care<br />

clearinghouse that “relates to the past, present ,or<br />

future physical or mental health or condition <strong>of</strong> an<br />

individual; the provision <strong>of</strong> health care to an individual,<br />

or the past, present, or future payment for<br />

the provision <strong>of</strong> health care to an individual” (45<br />

CFR § 160.103, 2008) Information is individually<br />

identifiable if it specifically identifies the individual<br />

or can reasonably be used to identify the individual<br />

(45 CFR § 160.103, 2008). The standards<br />

adopted under 42 CFR Part 2 are substantially<br />

similar; however, they relate specifically to information<br />

that establishes the “identity, diagnosis,<br />

prognosis, or treatment <strong>of</strong> any patient which are<br />

maintained in connection with the performance<br />

<strong>of</strong> any drug abuse prevention function conducted,<br />

regulated or directly or indirectly assisted by any<br />

department or agency <strong>of</strong> the United <strong>State</strong>s” [42<br />

CFR § 2.1(a), 2008)].<br />

It is important to note that while HIPAA does<br />

establish standards for the privacy (45 CFR Part<br />

164, Subpart E, 2008) and security (45 CFR Part<br />

164, Subpart C, 2008) <strong>of</strong> individually identifiable<br />

health information, this accountability is only one<br />

purpose <strong>of</strong> the legislation and implementing rule.<br />

HIPAA also allows for information to be responsibly<br />

made portable. For instance, it is important<br />

to remember that when an individual properly<br />

authorizes the use or disclosure <strong>of</strong> their information,<br />

HIPAA sets forth no roadblock to that use or<br />

disclosure [45 CFR § 164.508(b),2008]. Covered<br />

entities are also allowed to use protected health<br />

information for their own treatment, payment and<br />

operations and may disclose relevant information<br />

to other covered entities that need the information<br />

for these purposes [45 CFR § 164.506(c),<br />

2008]. HIPAA also establishes standards that enable<br />

information to be deidentified, effectively removing<br />

the need for further compliance (45 CFR §<br />

164.514, 2008). Finally, HIPAA sets forth limited<br />

instances when covered entities can choose to use<br />

or disclose protected health information without<br />

an authorization. A full list <strong>of</strong> these exceptions<br />

is found at 45 CFR § 164.512 and includes disclosures<br />

required by law [45 CFR § 164.512(a), 2008];<br />

to report abuse or neglect [45 CFR § 164.512(c),<br />

2008]; under court order [45 CFR §164.512(e),<br />

2008]; for law enforcement purposes [45 CFR 164<br />

§164.512(f), 2008]; and for research [45 CFR 164<br />

§164.512(i), 2008].<br />

While HIPAA applies to most <strong>of</strong> the nation’s<br />

health care providers, health plans and health<br />

care clearinghouses, Part 2 applies to substance<br />

abuse education, prevention, training, treatment,<br />

rehabilitation and research programs that are assisted<br />

by a department or agency <strong>of</strong> the United<br />

<strong>State</strong>s [42 CFR § 2.1(a),2008]. Indeed, there is a<br />

great deal <strong>of</strong> overlap where HIPAA covered entities<br />

also fall under the provisions <strong>of</strong> Part 2. Part 2<br />

providers should therefore be aware that to comply<br />

with both laws, the more stringent Part 2 will<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten control.<br />

Therefore, only disclosures allowed by both<br />

Part 2 and HIPAA can be made from Part 2 covered<br />

programs. A partial list <strong>of</strong> permitted disclosures<br />

is located at 42 CFR § 2.12(c). These include<br />

disclosures within the program [42 CFR §<br />

2.12(c)(3), 2008], and the reporting <strong>of</strong> child abuse<br />

[42 CFR § 2.12(c)(6), 2008]. Additionally, Part 2<br />

allows disclosures with a valid consent [42 CFR §<br />

2.33, 2008], for research [42 CFR § 2.52, 2008], in<br />

a medical emergency [42 CFR § 2.51, 2008], for<br />

audit and evaluation [42 CFR § 2.53, 2008], and<br />

by court order [42 CFR § 2.61, 2008]. Disclosures<br />

by court order are limited to specific circumstances<br />

that must be set forth in the court’s order [42 CFR<br />

§§ 2.63 through 2.67, 2008].<br />

This article establishes only a basic overview <strong>of</strong><br />

the permissive disclosures established by HIPAA<br />

and Part 2. It is important to know that both <strong>of</strong><br />

these regulations can be preempted by more stringent<br />

state law(s) [42 CFR § 2.20, and 45 CFR §<br />

160.203, 2008]. Because <strong>of</strong> the many intricacies<br />

<strong>of</strong> these laws themselves and the potential state<br />

overlay, covered entities are encouraged to have a<br />

strong working relationship with their privacy experts<br />

and legal counsel to ensure full compliance.<br />

Travis Kirchhefer is an Assistant Attorney<br />

General for the <strong>State</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Wyoming</strong>.<br />

REFERENCES<br />

42 USC § 290dd-2 (2006)<br />

42 USC § 1320(d) (2006)<br />

42 CFR Part 2 (2008)<br />

45 CFR Part 160 (2008)<br />

45 CFR Part 164 (2008)<br />

Legal Action Center (2006). Confidentiality and<br />

Communication: A Guide to the Federal Drug and<br />

Alcohol Confidentiality Law and HIPAA (6th ed.).<br />

New York, NY: Legal Action Center <strong>of</strong> the City <strong>of</strong><br />

New York, Inc.<br />

The Health Information Portability and Accountability<br />

Act <strong>of</strong> 1996, Pub L. No. 104-191 (codified<br />

at 42 USC § 1320(d), 42USC § 1395cc(a)(1), 42<br />

USC § 242k(k) (2006)).<br />

20 Wy o m i n g Nu r s e Re p o r t e r