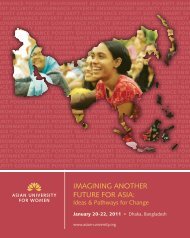

AUW 09-001 StudentBro2:Layout 1 - Asian University for Women

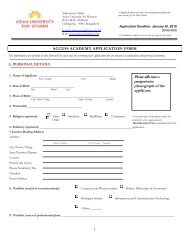

AUW 09-001 StudentBro2:Layout 1 - Asian University for Women

AUW 09-001 StudentBro2:Layout 1 - Asian University for Women

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

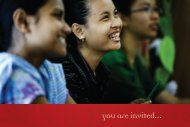

Profiles of Courage<br />

SIX WOMEN, ONE JOURNEY<br />

<strong>Asian</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Women</strong><br />

20/A M M Ali Road<br />

Chittagong – 4000, Bangladesh<br />

<strong>Asian</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Women</strong> Support Foundation<br />

1100 Massachusetts Avenue, Suite 300<br />

Cambridge, MA 02138, USA<br />

www.asian-university.org

The <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Women</strong><br />

Chittagong, Bangladesh<br />

The <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Women</strong> (<strong>AUW</strong>) is a leading institution<br />

of higher education based on the firm belief that education—especially<br />

higher education—provides a critical<br />

pathway to leadership development, economic progress,<br />

and social and political equality.<br />

Located in Chittagong, Bangladesh, <strong>AUW</strong> provides a<br />

world-class education to promising young women from<br />

diverse cultural, religious, ethnic, and socio-economic<br />

backgrounds from across Asia and the Middle East.<br />

While international in its vision and scope, the <strong>University</strong> is<br />

rooted in the unique context of the region. The <strong>Asian</strong><br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Women</strong> offers an educational paradigm that<br />

combines a liberal arts and sciences education at the<br />

undergraduate level with graduate professional training in<br />

the most urgently needed professions.<br />

At the heart of the <strong>University</strong>, is a civic and academic goal<br />

to cultivate successive generations of women leaders who<br />

possess the mindset, the determination, the skills and<br />

resources to address the challenges of social and economic<br />

advancement of their communities. Adhering to the<br />

belief that no group has a monopoly on talent, <strong>AUW</strong> is<br />

committed to providing a superior quality higher education<br />

to the region’s most promising young women, regardless<br />

of background. Consequently, <strong>AUW</strong> recruits talented<br />

students from poor, rural, and refugee populations who<br />

receive scholarship support to attend the <strong>University</strong> alongside<br />

those who do not need any economic support <strong>for</strong><br />

their education.<br />

<strong>AUW</strong> recognizes that there are many young women across<br />

Asia who possess exceptional talent, potential, and intellect,<br />

but lack the financial means and foundational skills to<br />

pursue a university education. The Access Academy is<br />

intended <strong>for</strong> those women who are the first in their families<br />

to enter university. It is a year-long pre -undergraduate<br />

program that prepares these students <strong>for</strong> a rigorous university<br />

education.<br />

The <strong>University</strong> ultimately seeks to empower its students by<br />

opening doors to new opportunities <strong>for</strong> making change. It<br />

seeks to graduate students who will pursue paths as<br />

skilled and innovative individuals and professionals, service-oriented<br />

leaders, and promoters of tolerance and<br />

understanding throughout the world. With a student body<br />

of approximately 3,000 women at full capacity and a target<br />

student to faculty ratio of 13:1, <strong>AUW</strong> is designed to<br />

be a relatively small but diverse institution that will ensure<br />

the full education of each student.<br />

In the following pages, you will hear the stories of six<br />

remarkable young women from the Access Academy as<br />

recorded by Bonnie Shnayerson. Prior to her senior year at<br />

the <strong>University</strong> of Pennsylvania in the United States, Ms.<br />

Shnayerson spent a month in Chittagong and captured a<br />

glimpse into their lives and world.<br />

Indrani * , Sreymom Pol, Sunita Basnet, Nazneen, Shakina<br />

Ismail, and Linda Gayathree each embody the spirit and<br />

vision of <strong>AUW</strong>. Our mission is to provide them with the<br />

tools they need to uncover their potential to change the<br />

world.<br />

*<br />

Indrani’s name has been changed to protect her privacy.<br />

3

From the Author<br />

Bonnie Shnayerson<br />

Within only a few days of visiting the Access Academy <strong>for</strong><br />

the <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Women</strong>, I was a convert. Like so<br />

many others, I was originally drawn halfway across the<br />

world to Bangladesh by <strong>AUW</strong>’s goal to empower rural,<br />

refugee and underprivileged women throughout Asia. The<br />

hope is that these young women, armed with a top-notch<br />

international education, will venture out into the world<br />

and assume positions of leadership, creating a network of<br />

strong, smart women across the continent that will trans<strong>for</strong>m<br />

gender roles well beyond their lifetimes. It was<br />

inspiring stuff. Although <strong>AUW</strong> was certainly compelling in<br />

theory, I had yet to be convinced in practical terms that<br />

any of this would be feasible. After spending only a couple<br />

of days observing, interviewing and learning, however,<br />

it became clear to me that <strong>AUW</strong>, even in its first chaotic<br />

stage, had already begun to achieve what it was striving<br />

<strong>for</strong> in the far future. I could not think of a better time to<br />

have visited. I saw the school at a time when it was struggling<br />

to stand on its feet, when things were still rough<br />

around the edges and when every day brought a host of<br />

new challenges. Yet it seemed to me that was precisely<br />

the moment that the spirit of the institution was established.<br />

And whatever the odds, they seemed to be getting<br />

it right.<br />

One of my most vivid memories of <strong>AUW</strong> will always be<br />

the rehearsal that prepared <strong>for</strong> the imminent arrival of the<br />

new head of the Academy. We were piled into a small hall<br />

that doubled as the gym space. It was hot, even with the<br />

fans on at full blast. The girls had been assembled to<br />

practice a song in her honor under the watchful supervision<br />

of Marion, a member of student government in possession<br />

of a celestial singing voice. I had been pulled to<br />

the front of the room by the school president after making<br />

the mistake of mentioning I used to sing a cappella, so I<br />

found myself in a perfect position to survey the girls. They<br />

seemed not to notice the heat or the monotony as they<br />

chatted and leaned against each other like they had been<br />

friends <strong>for</strong> years.<br />

Standing in a pool of sweat, I was relieved when the<br />

rehearsal finally ended and the dean of students called <strong>for</strong><br />

everyone to sing the Access Academy song. As the familiar<br />

notes rang out, the girls’ voices came together to <strong>for</strong>m<br />

one robust, united refrain. They sang of strength through<br />

sisterhood, the breakdown of boundaries, and women<br />

having the power to change the world. Gazing around the<br />

room at their bright, upturned faces, I suddenly found<br />

myself fighting back tears.<br />

At that moment I understood very clearly what this university<br />

would be in the future—indeed, what the Access<br />

Academy had already become. It was about hope. Some<br />

of these girls had been the first women in their villages to<br />

go to university. Many of them had to battle pervasive<br />

social stigmas and resistant family members to enroll. A<br />

large number came from severely disadvantaged backgrounds.<br />

When the Access Academy began in March, the<br />

girls were timid, shy, and homesick. After a mere five<br />

months under the tutelage of a small group of dedicated<br />

WorldTeach volunteers, however, the girls had blossomed<br />

into the confident young women I saw be<strong>for</strong>e me. Aware<br />

of how much they had overcome to be sitting in that<br />

room, I remember thinking that to observe their trans<strong>for</strong>mation,<br />

to see the glow of confidence on their faces, was<br />

like glow through association; one couldn’t help but be<br />

brightened by it.<br />

Five weeks of moments like those at the Access Academy<br />

instilled in me the firm belief that <strong>AUW</strong> will grow into the<br />

international university it aspires to become. One day<br />

down the line, this university will open its doors to young<br />

women all across the world. It will become a beacon of<br />

hope in a region where women are repeatedly marginalized<br />

and stripped of their voice. It was an honor to meet<br />

this initial batch of women, volunteers and students alike,<br />

who are paving the way <strong>for</strong> so many more to come. They<br />

have been given the chance to succeed. Almost as importantly,<br />

we have been given the responsibility and privilege<br />

to witness it.<br />

4

Indrani<br />

Age: 22 Home<br />

Country: Sri Lanka<br />

At some point in my three hours of interviewing Indrani * I<br />

began to cry. I was embarrassed, and even more so when<br />

she apologized. It was absurd that she should feel guilt <strong>for</strong><br />

wounding my American sensibility with the reality of her<br />

life. In my defense, it was her own tears that provoked<br />

mine; on top of the hardships she was so calmly recounting,<br />

it seemed too cruel, too unjust, to see tears gathering<br />

in her eyes. Unlike me, however, she fought hers back and<br />

kept talking.<br />

Indrani was the first person to apply to <strong>AUW</strong>, but that fact<br />

is far from her most distinguishing feature. She remains<br />

the prototype of what <strong>AUW</strong> hopes to achieve in its ambitious<br />

experiment to change the region, to catapult young<br />

girls of impoverished, rural, and refugee backgrounds into<br />

positions of leadership, giving voice to a silenced gender.<br />

Many girls cite increased confidence as a result of their<br />

five months at the Access Academy—one even claimed<br />

her friends no longer recognized her, her gregariousness<br />

that stark a change. Yet Indrani will always be removed<br />

from the fray, quietly disengaging herself to stand at a distance<br />

from the gripping banalities that so naturally <strong>for</strong>m<br />

the day-to-day lives of young girls. Clothes and boys are<br />

of little interest to her. Indeed, Indrani has started telling<br />

those who ask that she has a boyfriend at home, just so<br />

she can be left to her thoughts. It is not that she lacks<br />

confidence or is anti-social by nature, nor does she dislike<br />

the company of those individuals in particular. Indrani is<br />

simply twenty-two going on <strong>for</strong>ty and cannot pretend otherwise.<br />

A sorrow burns in her eyes, lit from within, and her<br />

days are laced with worries that no one but her nineteen<br />

Tamil classmates can ever understand. Skeptics may view<br />

<strong>AUW</strong>’s mission as quixotic, but Indrani will become the<br />

university’s greatest asset, its strongest proof that one<br />

opportunity, one changed life, can become the change<br />

felt by nameless more.<br />

Indrani was born in Jaffna, Sri Lanka in 1986. Her family is<br />

Tamil. Her father, an engineer, was killed be<strong>for</strong>e she was<br />

born. Her mother has never quite been the same, refusing<br />

to marry again and rejecting party invitations, or staying<br />

on the fringe of family functions. She now works as a college<br />

deputy principal and her son, Indrani’s older brother,<br />

just graduated from university in the capital city of<br />

Colombo. When Indrani was three years old, the family<br />

moved from the southern province to the north, fleeing<br />

the approaching Sri Lankan military.<br />

Life in war-torn Jaffna was lived under the constant threat<br />

of violence. Indrani wasn’t allowed to go to school by<br />

herself and when she returned home in the afternoons,<br />

her mother would make her go to an aunt’s house so<br />

she wouldn’t spend time alone. Such precautions, overzealous<br />

by many standards, are necessary in a city marked<br />

by an ethnic conflict that rages unbeknownst to much of<br />

the world.<br />

The Sri Lankan Civil War started in 1983, but the ongoing<br />

conflict is borne out of long-standing tension between<br />

two of Sri Lanka’s predominant ethnic groups: the<br />

Buddhist Sinhalese majority and the mainly-Hindu Tamil<br />

minority. During British colonial rule, resentment arose<br />

among Sinhalese toward the Tamils on the charge they<br />

were the beneficiaries of British favoritism. Sinhala nationalism<br />

blossomed after independence was achieved in<br />

1948, bolstering the ethnic divide, and feelings on both<br />

sides steadily grew more vitriolic until all-out war erupted<br />

in the early ‘80s. Since then, most of the fighting has<br />

taken place in the north between the Sri Lankan military<br />

and the Tamil rebel group, Liberation Tigers of Tamil<br />

Eelam (L.T.T.E.). Yet violence is pervasive throughout the<br />

island nation, as the Tamil Tigers’ devastating attacks in<br />

Colombo during the 1990s and the recent killing of Sri<br />

Lankan politician D.M. Dassanayak just outside the capital<br />

in 2008 demonstrate. A cease-fire brokered by Norway in<br />

2002 led many to hope <strong>for</strong> a long-lasting peace; continual<br />

fighting on both sides, however, rendered that peace<br />

agreement meaningless. In early 2008, the Sri Lankan government<br />

extracted itself from the truce and the war<br />

resumed in earnest.<br />

Amidst this political turbulence Indrani managed to<br />

become an excellent student. She notes with pride<br />

that Jaffna is Sri Lanka’s most educated city with a<br />

100% literacy rate, a feat that becomes more impressive<br />

due to the constant disruption the war poses. When<br />

Indrani was young, the Sri Lankan military captured<br />

Jaffna, a Tamil hub.<br />

Fighting meant electricity blackouts, and Indrani’s<br />

government school remained open only on days there<br />

was electricity, creating an educational environment that<br />

was erratic at best. As Indrani puts it, “If I have electricity<br />

today, I don’t have it tomorrow.” Frequent military<br />

*<br />

Indrani’s name has been change to protect her privacy.<br />

5

oundups also displaced the family<br />

from their home; <strong>for</strong> one or two<br />

months at a time. Indrani, her<br />

mother, and her brother would<br />

escape to temples and other communal<br />

spaces. It was a climate in<br />

which “Anything can happen at any<br />

time.” Although the family always set<br />

aside money and dried food to prepare<br />

<strong>for</strong> such events, they often had<br />

to rely on the generosity of the local<br />

NGO and people to provide <strong>for</strong><br />

them. Indrani was there<strong>for</strong>e in and<br />

out of schools from a young age. In<br />

fifth grade she only studied in school<br />

<strong>for</strong> two months—despite this, she<br />

got 23 rd rank in the country on her<br />

A-levels. On top of her considerable<br />

academic achievements, she also<br />

mastered classical dance and music.<br />

When asked how she juggled all her<br />

commitments, she simply replies,<br />

“I never waste my time.”<br />

Learning in such a climate imbued<br />

Indrani with a sense of injustice that<br />

demanded action from a young age.<br />

In seventh grade an orphan joined<br />

Indrani’s class. Indrani was in charge<br />

of collecting <strong>for</strong>ty rupees from each<br />

of her classmates, an extracurricular<br />

fee that the government did not<br />

cover, despite providing a free education<br />

to most Sri Lankans. When it<br />

was the new girl’s turn, she started<br />

to cry, explaining to Indrani that she<br />

had lost her entire family to the war<br />

and couldn’t af<strong>for</strong>d the <strong>for</strong>ty rupees.<br />

Indrani befriended the girl and visited<br />

her orphanage where she met<br />

one hundred orphans in all, many of<br />

whom had been orphaned by the<br />

violence. The visit left an indelible<br />

mark on Indrani. She began to collect<br />

money <strong>for</strong> the orphanage, saving<br />

a portion of her allowance in a tin<br />

every week. The night be<strong>for</strong>e her<br />

birthday she opened the tin to discover<br />

six hundred rupees. She smiles<br />

as she describes how she went to the<br />

orphanage the next day laden down<br />

with savings and birthday money to<br />

give to the children. It is a tradition<br />

she has continued ever since. Indrani<br />

decided early on that no matter what<br />

she studied in school, “I [would]<br />

emphasize my mind, works and<br />

deeds and thoughts, everything,<br />

through social work.”<br />

Beyond her father’s death, which she<br />

attests irreparably changed her<br />

mother but left Indrani and her<br />

brother, young as they were, relatively<br />

unscathed, Indrani’s life has been<br />

continually invaded by violence.<br />

These frequent acts of violence<br />

rocked Indrani’s already crumbling<br />

world. “Why do we have to study?<br />

This thing will happen to me also one<br />

day,” she thought. But determination<br />

to make a difference, to be a leader<br />

and to help her people, overtook<br />

fear, and learning gradually became<br />

her weapon. It is with deep resignation<br />

that she says: “Sometimes I feel<br />

those things. I suffered. [But] we have<br />

to accept everything on fate, or<br />

destiny. What to do?”<br />

In 2006, Indrani graduated from high<br />

school and abandoned her love of<br />

mathematics to pursue an internship<br />

at a hospital, entertaining the possibility<br />

of going to medical school<br />

because as a doctor, she believed<br />

she could help the most people. She<br />

studied yoga and meditation, both<br />

activities she now leads at <strong>AUW</strong>.<br />

She also spent time in the hospital’s<br />

psych ward, interacting with young<br />

women her own age struggling with<br />

mental illnesses, having lost husbands,<br />

brothers, or fathers in the<br />

war: “They didn’t [even] know how to<br />

dress,” she notes. She would come<br />

home in the evenings and feel lucky<br />

<strong>for</strong> perhaps the first time in her life,<br />

realizing, “I lost my father but I have<br />

my mother.” Indrani was then<br />

extended a coveted spot in the government<br />

bank’s training program.<br />

She trained <strong>for</strong> six months in Jaffna,<br />

teaching kids at a local orphanage<br />

on the weekends, be<strong>for</strong>e passing her<br />

banking exam to place 13 th in the<br />

entire country. She was subsequently<br />

offered a place as a permanent<br />

employee in the government’s bank<br />

in Colombo—a prestigious position<br />

<strong>for</strong> a girl barely 21-years-old. Her<br />

mother was ecstatic, but her excitement<br />

dwindled when Indrani applied<br />

to <strong>AUW</strong> soon after. Citing the large<br />

salary, Indrani’s mother berated her,<br />

saying, “This is enough <strong>for</strong> you.<br />

What’s the need to go [to <strong>AUW</strong>]?<br />

Your brother will look after you if<br />

you face any problems financially.”<br />

But Indrani has never viewed money<br />

as the goal—only the means to an<br />

end—and the end she seeks has<br />

little to do with material possessions.<br />

She desires only the “inner beauty<br />

of the people.”<br />

Still, she is far from naïve, and recognizes<br />

the importance of money in<br />

6

achieving her objectives: “We have<br />

to [first] think about the resources we<br />

have, and we have to maximize those<br />

resources,” she says. Indrani’s decision<br />

to attend <strong>AUW</strong> was rooted in<br />

her desire to know this world, to<br />

“get more experience about this<br />

life.” Only then did she feel she<br />

could become an effective leader.<br />

<strong>AUW</strong> has offered a respite from the<br />

war that has come to define Indrani’s<br />

existence. Within the Access<br />

Academy walls, the ethnic divide that<br />

has ravaged a country <strong>for</strong> decades<br />

has rapidly dissolved. At home they<br />

may be at war, but here, the Sri<br />

Lankan students, nineteen Tamil and<br />

eleven Sinhalese in all, are merely a<br />

group of girls whose shared nationality<br />

in a <strong>for</strong>eign place means instant<br />

camaraderie. Both Tamil and<br />

Sinhalese students are quick to identify<br />

that Sri Lanka’s political parties<br />

are responsible <strong>for</strong> this conflict, not<br />

each other. The two groups seem to<br />

make concerted ef<strong>for</strong>ts to circumvent<br />

any inherent friction.<br />

These friendships, however, are not<br />

always immune to strain. Tamils have<br />

borne the brunt of the war <strong>for</strong><br />

decades; the Sinhalese students, who<br />

have been by and large sheltered<br />

from the violence, can never truly<br />

understand what life is like as a<br />

Tamil. Like a soldier on leave from<br />

war, Indrani also struggles to find a<br />

place among girls from peaceful, stable<br />

countries who know nothing of<br />

her daily struggles, who “have everything,<br />

just not the finances.” “How<br />

can I explain?” she wonders, “They<br />

couldn’t understand.” She and the<br />

other Tamil students spend their<br />

afternoons hastily checking the<br />

Internet <strong>for</strong> any news from home,<br />

looking <strong>for</strong> reports on the latest<br />

suicide bomber, explosion, or raid,<br />

and praying <strong>for</strong> those still there.<br />

“Sometimes I can’t control my mind—<br />

it goes to my home, to my mother,<br />

my brother,” Indrani confesses. It is<br />

perhaps a result of these worries that<br />

Tamil students rarely complain about<br />

the food or the heat, as other students<br />

are apt to do: “This is more<br />

than enough <strong>for</strong> us,” says Indrani.<br />

Despite sometimes feeling alienated<br />

from her classmates, Indrani is still<br />

very involved with the community.<br />

She and a few other students established<br />

and now lead the community<br />

service club. Every weekend the<br />

group visits a different orphanage<br />

in Chittagong; their latest project<br />

involves taking homeless children<br />

off the streets and teaching them.<br />

Indrani is thrilled to be involved:<br />

“I came here to study, it’s true, but<br />

my main purpose is to do social<br />

work,” she says. She wants to “know<br />

the condition of here,” pointing to<br />

the many differences between Sri<br />

Lanka and Bangladesh. She has also<br />

made rapid strides in mastering<br />

English. Be<strong>for</strong>e enrolling in the<br />

<strong>University</strong>, Indrani knew very little of<br />

the language, having always been<br />

taught in her native tongue.<br />

When I give Indrani a hug at the end<br />

of the interview, her compact, athletic<br />

body relaxes only momentarily<br />

be<strong>for</strong>e pulling away, speculating<br />

aloud how many people have died in<br />

her country during the course of our<br />

conversation. “More than seven people,<br />

maybe,” she thinks. Her voice<br />

rises as she tries one last time to<br />

make the American understand the<br />

“real condition of existence” <strong>for</strong><br />

Tamils in Jaffna. She says, “We have<br />

to accept. If we go outside we don’t<br />

know what will happen to us. That’s<br />

why we have a habit to talk about<br />

God. Mentally they want to weaken<br />

us. But they can’t… day by day it’s a<br />

normal thing <strong>for</strong> us.”<br />

For a young woman who yearns to<br />

learn how to lead, Indrani’s innate<br />

wisdom and quiet confidence ensure<br />

she is already well on her way.<br />

7

Linda Gayathree<br />

Age: 19<br />

Home Country: Sri Lanka<br />

“Once upon a time there was a very beautiful house<br />

covered with coconut trees and beautiful flower pots.<br />

There was a very beautiful sea beach in front of the<br />

house. This house… belong[ed] to a nice family. Every<br />

day they started their lives with beautiful sceneries. Cool<br />

sea winds kissed them when they opened their windows.<br />

Dancing coconut trees tried to show a beautiful scene<br />

<strong>for</strong> them. At sunset they used to take their tea break.”<br />

“This house was mine.”<br />

The day the sea came alive with vengeance, the world<br />

was silent. A gloomy pall draped itself over the canopy<br />

of the Sri Lankan sky as birds and insects muffled their<br />

morning chatter, but attacked their activities with renewed<br />

zeal. The air felt heavy as nature’s most destructive <strong>for</strong>ces<br />

steadily gathered strength off shore. Linda Gayathree<br />

awoke that day in the house she loved, with the parents<br />

she adored, next to the sea she worshipped, and instantly<br />

noted the change. “I thought the sea had <strong>for</strong>gotten to<br />

wake up because it was so still,” she remarks. She<br />

watched the scurrying animals and insects and pondered<br />

their sudden frenzy. “I tried to understand them,” she<br />

says, “but [they] just left me confused.” It was<br />

December 26 th , 2004.<br />

Linda grew up on the coast of Sri Lanka’s island nation in<br />

the southern province. Her small house was built right on<br />

the sand, and she spent an idyllic childhood playing along<br />

golden beaches that have been called some of the most<br />

beautiful in the world. Her mother was a housewife and<br />

her stepfather supported her, Linda, and Linda’s younger<br />

sister, with his modest earnings as a fisherman. The family<br />

was so tightly knit that Linda rarely ventured outside her<br />

home without her mother. Even a simple shopping trip<br />

involved her mother’s caring supervision.<br />

Not surprisingly, Linda is unusually affectionate—a girl<br />

whose desire to give love and be loved is immediately<br />

apparent. But she is also quick, driven, and articulate. Her<br />

passion <strong>for</strong> literature and her instinctive feel <strong>for</strong> words—<br />

even in a second language—trans<strong>for</strong>m her written prose<br />

into near-poetry. She approaches her studies with a grave<br />

seriousness that ensured her superior per<strong>for</strong>mance in Sri<br />

Lanka’s competitive education system.<br />

The day the sea rose, Linda showered and dressed as<br />

usual <strong>for</strong> school, despite the scent of danger in the air. As<br />

a devout Buddhist, Linda would pray to Buddha and<br />

receive her mother’s blessings over breakfast every morning<br />

be<strong>for</strong>e leaving the house. But when Linda walked into<br />

the kitchen, she discovered her mother standing as still as<br />

the ocean she stared at, her eyes trained on the hushed<br />

landscape. She turned to her eldest daughter and ordered<br />

her to stay home that day, describing the atmosphere as<br />

“not good.” Linda, always the dedicated student, ignored<br />

her mother’s precautions. For the first time in her life, she<br />

went off to school with neither breakfast nor her mother’s<br />

blessing, the ritual smothered in the silence hanging<br />

between a mother and her disobedient daughter. The<br />

time was 9:35 AM.<br />

Linda walked the short distance to the bus stop to discover<br />

it eerily empty. She was waiting <strong>for</strong> her friend<br />

Supuni—“because I never went [to] classes without<br />

Supuni”—when she heard shouting. A boy ran by, calling<br />

to her: “‘Sister, the sea is coming, please run!’” As the<br />

words tumbled from his mouth, frothing seawater came<br />

gushing in a torrent down the street. The “white color sea<br />

waves” coursed toward Linda, trying “to kiss my legs,” as<br />

shock and fear rooted her to the spot. “I <strong>for</strong>got what I was<br />

doing there. I couldn’t do anything,” she says. Out of<br />

nowhere, Supuni appeared and grabbed Linda’s hand,<br />

pulling her into a run. It was utterly bewildering to see the<br />

sea in the streets. “I was unable to think what had happened,”<br />

Linda recalls. “I’m so confused but I ran.”<br />

8

Wading through the swirling waves,<br />

Supuni and Linda found their way to<br />

a nearby boys’ school. They took<br />

shelter in the building as the storm<br />

raged outside. “We were safe <strong>for</strong><br />

now,” Linda says, “but we didn’t<br />

know what had happened to our<br />

families.”<br />

This was no ordinary storm. A<br />

tsunami, unleashed by the fifthlargest<br />

earthquake in a century, had<br />

crashed into the coast of Sri Lanka. 1<br />

An undersea tremor that became a<br />

magnitude 9.0 earthquake on the<br />

floor of the Indian Ocean had triggered<br />

a series of devastating<br />

tsunamis across the coasts of southern<br />

Asia. Indonesia, Sri Lanka, India,<br />

and Thailand were the hardest hit.<br />

One of the deadliest natural disasters<br />

in history, the December 26 th tsunami<br />

was responsible <strong>for</strong> the deaths of tens<br />

of thousands of people across eleven<br />

countries. Indonesia suffered the<br />

most casualties with a death toll of<br />

242,347. Sri Lanka came in second<br />

with 30,974 dead and another<br />

100,000 displaced. 2<br />

The day crawled by without any contact<br />

between Linda and her family. As<br />

each further hour passed without any<br />

sign of her parents, Linda became<br />

more certain they had been killed.<br />

Her parents, after taking refuge in<br />

her grandparents’ home, were<br />

equally convinced of her death.<br />

“They searched me among all the<br />

dead bodies,” Linda says with traces<br />

of horror and sadness. Within less<br />

than twelve hours, 2,000 corpses had<br />

already been collected at the hospital.<br />

“Fortunately,” Linda says, “I leave<br />

with my life.”<br />

By six in the evening, Linda felt brave<br />

enough to look outside. Venturing<br />

out onto the fifth-floor balcony of the<br />

boys’ school, she spied a man who<br />

resembled her uncle. Closer inspection<br />

revealed that he was indeed her<br />

relative—but “he looked like a mad<br />

man,” she notes. Shouting and crying,<br />

Linda ran to him. As she came<br />

bounding down the stairs, he fainted.<br />

“He never thought I live,” Linda says.<br />

He had spent the entire day sorting<br />

through rubble and staring into the<br />

bloated faces of the dead in search<br />

of his niece.<br />

The storm had severed all phone<br />

connections, preventing Linda from<br />

reaching the rest of her family.<br />

Anxious to end their worries, she and<br />

her uncle quickly set out <strong>for</strong> home<br />

only to discover the roads blocked<br />

by bodies. It was impossible to walk.<br />

They had to resort to the long way<br />

back, picking their way home along<br />

jungle paths.<br />

When they finally reached Linda’s<br />

grandparents’ home, “My poor<br />

mother’s face bloomed like a flower.<br />

She kissed me a lot,” Linda recalls.<br />

Her neighbors rejoiced as well; the<br />

close community had already begun<br />

to fast in mourning. “[My neighbors]<br />

love me a lot; I think I am a good<br />

girl, that’s why,” Linda says.<br />

The family gathered together to<br />

exchange their stories, showering<br />

each other with hugs and kisses.<br />

When the tsunami first hit, Linda’s<br />

mother, a small woman, had closed<br />

the door against the waves, securing<br />

the house as best she could be<strong>for</strong>e<br />

running. Linda’s uncle found her<br />

fighting against the water and carried<br />

her to the grandparents’ house<br />

nearby. At that point, as Linda tells it,<br />

her father was far out to sea on his<br />

fishing boat. After learning about the<br />

tsunami from satellite images, he<br />

feared the worst. Overcome with<br />

grief, he swallowed a cocktail of the<br />

drugs he always carried with him<br />

after suffering a recent heart attack.<br />

Linda’s eyes begin to water at this<br />

point in the story. “I think my father’s<br />

the gift of god,” she says. “I love him<br />

very much.” Her father survived the<br />

dose, <strong>for</strong>tunately, and made it back<br />

to shore to reunite with his family.<br />

“In my life, I<br />

firmly believe<br />

that I have some<br />

extraordinary<br />

talents to do<br />

something<br />

constructively <strong>for</strong><br />

others. If I get an<br />

opportunity at<br />

<strong>AUW</strong>, I hope I<br />

could easily fulfill<br />

my dreams.”<br />

1<br />

Department of Census and Statistics, Sri Lanka, accessed at http://www.statistics.gov.lk/Tsunami/ on August 26, 2008. Last updated on December 22, 2005.<br />

2<br />

CNN, “Tsunami Death Toll,” accessed at http://www.cnn.com/2004/WORLD/asiapcf/12/28/tsunami.deaths/ on August 26, 2005, posted on February 22, 2005.<br />

9

The months following the tsunami<br />

were challenging <strong>for</strong> the Gayathree<br />

family. Although they counted themselves<br />

among the lucky ones, the sea<br />

had still washed away their house<br />

and all their possessions. The family<br />

was <strong>for</strong>ced to move into Linda’s<br />

grandparents’ house, living alongside<br />

her grandfather, grandmother,<br />

three uncles, aunt, father, mother,<br />

and younger sister. The house consisted<br />

of only two rooms. To make<br />

matters worse, the tsunami hit on<br />

the eve of Linda’s Advanced-Level<br />

(A-Level), the nation-wide qualification<br />

exam to graduate from high<br />

school. It was hard to find a place<br />

to study and even harder to get a<br />

good night’s sleep. With pride,<br />

Linda describes not only passing<br />

her A-Levels, but doing very well.<br />

She was offered a place at one of<br />

the best management universities<br />

in the country. The government<br />

eventually donated a new house to<br />

her family in a rural area, but Linda<br />

says, “It’s not like our home. It’s too<br />

small. Now we haven’t our beautiful<br />

sceneries, especially our sea.”<br />

Her per<strong>for</strong>mance on the A-Levels, so<br />

soon after the tsunami, was nothing<br />

less than a triumph. With death at<br />

the door and her country in pieces,<br />

Linda managed to sustain academic<br />

excellence. Soon after, she was<br />

offered a place at <strong>AUW</strong>. “I never<br />

think I can do these things,” Linda<br />

says. “But I did it.”<br />

10

Nazneen<br />

Age: 20<br />

Home Country: Pakistan<br />

Some of the most important decisions we face, we face<br />

alone. These are the decisions that go against our parents’<br />

wishes or diverge with cultural norms. They are also the<br />

decisions that <strong>for</strong>ce us to define who we are, and who we<br />

are to become.<br />

For twenty-year old Nazneen, enrolling in the <strong>Asian</strong><br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Women</strong> was one such decision. Nazneen<br />

grew up in a poor, remote village in the Hunza Valley, a<br />

mountainous area in northern Pakistan near the Chinese<br />

border. When she was a child, the village houses were<br />

made of mud, there wasn’t enough food to eat, and she,<br />

along with her neighbors, drank water from the nearby<br />

stream. It was only with the development of a historical<br />

site, the Altit Fort, that the village began to prosper, and<br />

amenities like running water, brick buildings, roads,<br />

schools, and a government hospital were introduced into<br />

the area.<br />

The gender disparities confronting Nazneen in Pakistan’s<br />

education system were <strong>for</strong>midable. According to a 2004<br />

estimate, the Pakistani government spends only about 1<br />

percent of its GDP on education. Chronic underinvestment<br />

in education has led to an overall literacy rate of<br />

49.9 percent and an adult female literacy rate of only 36<br />

percent. In contrast, the male literacy rate is 63 percent<br />

(2005 census) 1 . The gap between gender literacy rates has<br />

increased in past decades, despite the government’s best<br />

ef<strong>for</strong>ts to launch educational initiatives aimed at closing it.<br />

Gender disparities in education have been further<br />

widened by cultural norms: women are expected to adopt<br />

traditional roles within the family that severely restrict<br />

mobility and access to the public sphere. 2<br />

Nazneen is the daughter of a farmer who also works as a<br />

laborer-by-hire in construction. Her mother operates a<br />

small tailoring business out of their home that allows her<br />

to also take care of the family. The two parents stretched<br />

their income to send six of their seven children to school;<br />

Nazneen, the eldest, became the exception after winning<br />

a scholarship to study in an English medium school. Her<br />

college was in a distant neighboring village, and with no<br />

transportation system to speak of, Nazneen rose early<br />

every morning to walk the long distance. After walking<br />

home in the afternoons, she tutored thirty young students<br />

in her home <strong>for</strong> three or four hours, then helped her<br />

mother with dinner, and finally turned to her studies. Like<br />

most of the people in the Hunza Valley, Nazneen is an<br />

Ismaili Muslim, a breakaway Shia sect that follows the<br />

teachings of the spiritual leader His Highness Prince Karim<br />

Aga Khan IV.<br />

Nazneen heard about <strong>AUW</strong> and its offer of full scholarships<br />

from Aga Khan Culture Services Pakistan, the NGO<br />

she had joined. Prince Karim Aga Khan heads an organization<br />

called Aga Khan Development Network that does<br />

good works around the world. Its many branches in<br />

Pakistan include the NGO Nazneen worked <strong>for</strong>, which was<br />

involved with the Altit Fort restoration in her region.<br />

Nazneen was responsible <strong>for</strong> overseeing their interns.<br />

Upon learning about <strong>AUW</strong>, Nazneen told nobody but her<br />

parents. She alerted them that she planned to take the<br />

test, but offered no further specifics. She went through the<br />

entire application process without breathing a word to<br />

anyone else in her village—friends, relatives, and neighbors<br />

remained oblivious to her standing on the cusp of<br />

change. When she learned of her acceptance, Nazneen<br />

sought advice from the most educated members of her<br />

community, her teachers and the NGO: “They told me<br />

what is right, and what is good <strong>for</strong> me. And I believed<br />

them.” She confided in only these select few, apparently<br />

fearing that others in her village might disapprove and<br />

somehow <strong>for</strong>ce her to give up her emerging plan.<br />

The quiet determination necessary to remain silent on<br />

such a decision offers a glint of something harder beneath<br />

Nazneen’s girlish surface. When she speaks, her English is<br />

inconsistent at best and these frequent mistakes unleash<br />

cascades of giggles. Her admission of secrecy seems out<br />

of place <strong>for</strong> a person whose jovial laughter punctuates<br />

every conversation. But it’s there, in the quiet lull of her<br />

voice as she describes the obstacles posed by cultural<br />

expectation, so pervasively interwoven into the fabric of<br />

Pakistani life, her strong, carved features studying the<br />

1<br />

CIA World Factbook, Pakistan, accessed at https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/print/pk.html on August 25, 2008, last updated<br />

August 21, 2008.<br />

2<br />

Coleman, Isobel, “Gender Disparities, Economic Growth and Islamization in Pakistan,” Woodrow Wilson International Center <strong>for</strong> Scholars, July 2004.<br />

Accessed at http://www.cfr.org/publication/7217/gender_disparities_economic_growth_and_islamization_in_pakistan.html, August 4, 2008.<br />

11

“After getting<br />

education I can<br />

help with my six<br />

siblings. I can<br />

support them<br />

to study at<br />

institutions, so<br />

they can do<br />

something <strong>for</strong><br />

others; in this<br />

way, we can<br />

do something.”<br />

floor. For a brief moment, be<strong>for</strong>e her<br />

face rearranges like puzzle pieces<br />

and the giggling ensues, one<br />

glimpses the demeanor of a grown<br />

woman.<br />

Nazneen finally told her village. In all<br />

likelihood, she told just a few relatives,<br />

but as she notes, “If we say<br />

one thing in our home, the whole village<br />

knows.” There was an immediate<br />

outcry. Friends, relatives, and<br />

neighbors all objected, but Nazneen<br />

remained steadfast. She explains,<br />

“Other people were uneducated,<br />

they can’t know. They just say there’s<br />

conflict [between Pakistan and<br />

Bangladesh], and it’s a poor country,<br />

but they don’t know the importance<br />

of education.” Nazneen had anticipated<br />

these reactions and arranged<br />

accordingly. The Aga Khan NGO she<br />

worked <strong>for</strong> helped her secure her<br />

passport and visa be<strong>for</strong>e she went<br />

public with her decision. When her<br />

uncles, who wielded considerable<br />

power in the village’s tribal system,<br />

ordered her to stay at home, she<br />

was already one step ahead of them.<br />

“They refuse me,” she says, “but<br />

they can’t do anything.”<br />

The enormity of what she had done<br />

hit Nazneen on the plane to<br />

Bangladesh, her first time outside<br />

Pakistan. She admits she cried the<br />

whole way (and <strong>for</strong> the next three<br />

months). Yet an unexpected and new<br />

community awaited Nazneen: her<br />

religious sect, predominant in the<br />

hills of her valley, had made its way<br />

to Chittagong. With the help of<br />

Kamal Ahmad, she discovered an<br />

Ismaili center, and once the community<br />

was alerted to her presence —<br />

“They know I’m here, a religious girl<br />

is living in Chittagong”—she was<br />

quickly welcomed into its folds.<br />

She enthusiastically attended the<br />

programs and met the center’s members,<br />

many of them also from different<br />

countries. In the spring, Prince<br />

Karim Aga Khan IV visited Dhaka at<br />

the invitation of the Bangladeshi<br />

Government. The visit enabled the<br />

Prince to <strong>for</strong>ge a relationship with the<br />

groundbreaking of a school he had<br />

founded. The Ismaili center sponsored<br />

a trip to Dhaka to bear witness<br />

to this occasion. Nazneen stayed in<br />

the program director’s house <strong>for</strong> a<br />

week in the capital during which, she<br />

recalls with a mischievous smile,<br />

“They spoiled me.” She also<br />

attended a banquet in the Prince’s<br />

honor, where she was seated near<br />

members of the government and<br />

some of the Prince’s most devout<br />

followers who had trailed him from<br />

India. It was a unique opportunity<br />

<strong>for</strong> Nazneen. The Prince now lives in<br />

Paris and seldom visits Pakistan,<br />

maybe once every ten years. “We<br />

get this kind of chance very rarely,"<br />

she says. "We are his followers and<br />

we respect him.”<br />

<strong>AUW</strong> has also been an experiment<br />

in religious diversity <strong>for</strong> Nazneen.<br />

Religious beliefs are strictly homogenous<br />

in her home region: faith begins<br />

and ends with Ismaili Islam. Until<br />

<strong>AUW</strong>, she had never be<strong>for</strong>e met<br />

anyone of a different religion. She<br />

was relieved to discover that all<br />

the students follow their separate<br />

customs in peace: “We all say our<br />

prayers in our own styles, it does<br />

not create a problem,” she says.<br />

12

Although she misses her village and<br />

can only speak to her parents every<br />

two weeks because the phone calls<br />

are too expensive, Nazneen claims<br />

that the teachers have made <strong>AUW</strong><br />

home. One hundred and thirty girls,<br />

plus faculty and administrators, study,<br />

work, and live in close proximity on<br />

ten floors. Despite the possibility<br />

of conflict, she says, every person<br />

“acts like our family member.”<br />

Nazneen’s real family members<br />

tend to be less welcoming. Since<br />

she arrived at <strong>AUW</strong> five months ago,<br />

her uncles have refused to speak to<br />

her. Her mother bears the brunt of<br />

their anger. They hold her responsible<br />

<strong>for</strong> allowing Nazneen to leave the<br />

home and disgrace the family within<br />

the community. She reveals little to<br />

Nazneen about the gravity of the<br />

situation. Nazneen only knows:<br />

“They are not good with her.”<br />

Despite pressures that continue to<br />

radiate across country borders,<br />

Nazneen cherishes the opportunity<br />

<strong>AUW</strong> has presented her and her family.<br />

“I feel happy because if I was<br />

[home], it would become difficult<br />

<strong>for</strong> me to study there because my<br />

parents weren’t able to continue my<br />

education,” she says. She plans to<br />

pass on the gift of free education<br />

in the future, using her degree to<br />

support her four brothers and two<br />

sisters as they go through school,<br />

while taking the burden off her parents.<br />

“After getting education I can<br />

help with my six siblings. I can support<br />

them to study at institutions,<br />

so they can do something <strong>for</strong> others;<br />

in this way, we can do something.”<br />

She hopes to empower women in<br />

her village, working to improve the<br />

accessibility of education by offering<br />

more scholarships from a position<br />

of leadership in her village’s school<br />

system. Nazneen points to the <strong>AUW</strong><br />

teachers as inspiration. Because of<br />

them, she says, “We get courage.<br />

I want to do the same.”<br />

13

Shakina Ismail<br />

Age: 19<br />

Home Country: Bangladesh<br />

Shakina Ismail was already standing outside by the time<br />

her guests started to filter through the Access Academy’s<br />

double glass doors. She squinted in the brilliant<br />

Bangladeshi sunlight—the trip had fallen on the only day<br />

of clear skies in the past two weeks. Evidently the monsoon<br />

season had arrived. She was dressed in her best,<br />

her shalwar kameez an electric turquoise and pink combination,<br />

embroidered with sequined flowers she had<br />

designed and sewed herself. Her face, normally bare,<br />

was flushed with makeup, her eyes defined with a dark<br />

pencil behind her rimless glasses and her lips shaded<br />

a rich maroon.<br />

Shakina grew up in a poor village outside of Chittagong<br />

city, one of Bangladesh’s largest cities and its primary<br />

seaport. Her village lies off the main highway that snakes<br />

from the bustling innards of the city, past the lush green<br />

rice paddy fields of the countryside, to a small town where<br />

her father earns his living. Here he sells umbrellas in the<br />

rainy season and religious outfits out of a small shop. A<br />

turn down the narrow street that leads to Shakina’s village<br />

offers an instant haven from the havoc of the main road.<br />

The path is lined with low-hanging palm trees and the<br />

traditional Bangladeshi house, a seemingly fragile structure<br />

made of interwoven sticks. Cows and their herders,<br />

villagers, rickshaws, and the occasional CNG (threewheeler<br />

taxi), pass down this street.<br />

The village itself represents the way many Bangladeshis<br />

live in rural areas. Children bathe in the same pond that<br />

women wash their clothes in. The pond is straddled by<br />

paths that lead to a small primary school, a simple building<br />

that nevertheless shows signs of development in<br />

recent years. A water pump provides water to the villagers.<br />

Towering haystacks flanked by tall trees feed the<br />

often-emaciated cow that some of the wealthier families<br />

own. Children play barefoot and tend to be clothed in<br />

very little, their parents unable to af<strong>for</strong>d new clothing.<br />

Education has declined; the pressure to earn money and<br />

feed one’s family is more urgent than learning. As Shakina<br />

notes, “the majority of my relatives and neighbors are<br />

not educated. They are not conscious of education.”<br />

During the car ride to her village, Shakina answered a<br />

steady stream of phone calls from her family, doling out<br />

instructions in rapid Bangla. It was, after all, a momentous<br />

occasion. A handful of <strong>AUW</strong> faculty members, visitors, and<br />

the world-renowned photographer Shahidul Alam were<br />

accompanying Shakina to her home to document the<br />

background of a typical <strong>AUW</strong> student. The villagers had<br />

prepared <strong>for</strong> days—outsiders, especially <strong>for</strong>eigners, rarely<br />

visited the area. Shakina sat in the back of the van like a<br />

colorful bird preening her feathers, her chest puffed up<br />

with pride. The significance of this event, honoring a<br />

daughter’s homecoming instead of the son’s, was not<br />

lost on us.<br />

Shakina has a studious look, the air of someone who has<br />

spent little time outdoors and is happiest poring over a<br />

book. She credits her parents <strong>for</strong> instilling her with a love<br />

of learning that has in turn generated a wealth of academic<br />

achievements. Unlike many other parents in the<br />

village, Shakina’s parents, “not so educated” themselves,<br />

have always valued the importance of schooling their<br />

children, including their daughters. Shakina is the eldest<br />

of two sisters and one brother. Despite considerable<br />

scorn from relatives and neighbors alike, her parents have<br />

always made the financial sacrifices necessary to give<br />

Shakina every possible schooling opportunity, including<br />

expensive private tutoring. The villagers loudly criticized<br />

Shakina’s parents <strong>for</strong> such decisions. “They always tease<br />

my parents, [saying], ‘why are you spending money on<br />

your daughters. You should just marry them,’” Shakina<br />

notes.<br />

Shakina’s father is one of the wealthier men in the village;<br />

umbrellas and religious objects apparently sell well in<br />

a rainy country beset by cruel floods. Shakina’s mother<br />

is a housewife. Her family, along with her grandparents,<br />

uncles, and aunts, live in a concrete compound with an<br />

impressive metal gate, a notable exception to the village’s<br />

wooden houses. They also have their own cow. This<br />

wealth, however, is only relative to the poverty of the<br />

other villagers. Shakina remains one of <strong>AUW</strong>’s most underprivileged<br />

students. The fact that her parents squander<br />

whatever financial edge they may enjoy on education<br />

14

aises rankles among their neighbors.<br />

But Shakina’s parents simply say:<br />

“We don’t want a big house or a<br />

big car. We just want to settle our<br />

daughters so they can do something<br />

<strong>for</strong> society.”<br />

Shakina attended primary school on<br />

a government scholarship until class<br />

five, and then passed an examination<br />

to become the first student to win a<br />

scholarship from this particular school<br />

in thirty years. She went through<br />

class six and seven on scholarship,<br />

and won another scholarship <strong>for</strong><br />

high school in class eight. She<br />

earned yet another scholarship to<br />

study at one of the top colleges in<br />

Chittagong be<strong>for</strong>e being accepted<br />

on full scholarship to <strong>AUW</strong>.<br />

By the time the van pulled into<br />

Shakina’s village, a large crowd of<br />

children had gathered. A pack trailed<br />

us throughout the day; amusement<br />

and curiosity were written all over<br />

their faces. Shakina fluttered ahead,<br />

greeting family and friends. She led<br />

us to her primary school where uni<strong>for</strong>m-clad<br />

school children showered<br />

her with flower petals and the head<br />

of school gave her a bouquet. The<br />

principal also pointed out Shakina’s<br />

name, inscribed on a plaque that was<br />

featured prominently in her office.<br />

Shakina then arrived to her house<br />

to find a feast of fruit, hot dishes,<br />

pastries, and desserts waiting. Aunts,<br />

uncles, sisters, cousins, and of<br />

course, her proud parents, crowded<br />

into the small living room to eagerly<br />

ply their guests with food. Neighbors<br />

observed from atop their roofs and<br />

children crouched underneath the<br />

compound’s gate to catch a glimpse<br />

of the gathering. It was, needless to<br />

say, a celebrity’s welcome.<br />

Shakina first heard about <strong>AUW</strong> from<br />

her father while she was studying <strong>for</strong><br />

her medical exam. She had attended<br />

only ten classes at her Chittagong<br />

university by this point. She remembers<br />

her first reaction to <strong>AUW</strong>. “It<br />

was near from Foy’s Lake,” she<br />

recalls, giggling. “I was so happy, I<br />

don’t know why, [but] I’ll apply to<br />

that university.” Foy’s Lake is<br />

Chittagong’s one and only amusement<br />

park. Her interest mounted as<br />

she went through the application<br />

process—the day she heard back<br />

from the <strong>University</strong> was spent in a<br />

state of breathless suspense. She<br />

accepted her offer from <strong>AUW</strong> after<br />

failing her medical exam. Her parents,<br />

having groomed her to be a<br />

doctor her entire life, now say it was<br />

fate she failed; it allowed her to<br />

come to <strong>AUW</strong>.<br />

“<strong>Women</strong> are always neglected, if they’re<br />

educated or not… I think if a girl who has a<br />

good career like a boy, then never a boy<br />

can torture her. Boys can get an opportunity<br />

to study, but girls can’t – they get married.<br />

Boys criticize girls easily. I think if I can show<br />

something <strong>for</strong> girls, then I think they will<br />

realize women can do like a boy.”<br />

Since enrolling in the Access<br />

Academy, Shakina’s interests have<br />

shifted to environmental science and<br />

in<strong>for</strong>mation technology. She plans to<br />

choose the subject that will be the<br />

most beneficial to her country. “I<br />

want to be one of the top students<br />

at <strong>AUW</strong>,” she says. She has also<br />

embraced karate as an extracurricular,<br />

calling all self-defense classes<br />

“very necessary <strong>for</strong> women. At least<br />

we feel we are more strong.” After<br />

earning her international degree,<br />

Shakina plans on coming back to<br />

work in her country, particularly in her<br />

village: “I want to do something <strong>for</strong><br />

women especially.”<br />

Shakina identifies education as the<br />

tool that will trans<strong>for</strong>m the gender<br />

roles maintained by an older generation.<br />

Her father, <strong>for</strong> all his encouragement,<br />

used to tell Shakina: “You are<br />

not my daughter, you are my son.’<br />

Her uncle, aunts, and grandparents<br />

were all against sending Shakina to<br />

university. Now, Shakina’s younger<br />

sister, aged 18, plans to follow in her<br />

sister’s footsteps and apply to <strong>AUW</strong>.<br />

It seems the precedent has been set.<br />

“<strong>Women</strong> are always neglected, if<br />

they’re educated or not,” Shakina<br />

says. “I think if a girl who has a good<br />

career like a boy, then never a boy<br />

can torture her. Boys can get an<br />

opportunity to study, but girls can’t—<br />

they get married. Boys criticize girls<br />

easily. I think if I can show something<br />

<strong>for</strong> girls, then I think they will realize<br />

women can do like a boy.”<br />

15

Sreymom Pol<br />

Age: 18<br />

Home Country: Cambodia<br />

A haze of traffic and people swirled around 17-year-old<br />

Sreymom Pol. She was standing in the streets of Phnom<br />

Penh, luggage in hand, having just arrived in the capital<br />

after a journey of 140 kilometers from her village in the<br />

Cambodian countryside. It was the farthest from home she<br />

had ever traveled and her dark brown eyes grew wide<br />

staring at the strange cityscape. As the recipient of a government<br />

scholarship to study chemistry, Sreymom had<br />

looked to the few girls from her village who had preceded<br />

her to the city: “I saw that they can go study by themselves,<br />

so I think maybe I can.”<br />

Yet life in Phnom Penh was not easy <strong>for</strong> a teenager, the<br />

baby of the family, who was living apart from her mother<br />

and sisters <strong>for</strong> the first time. In the first month, Sreymom<br />

lived ten kilometers away from her college, braving the<br />

hectic city streets every day by bicycle. She was soon<br />

awarded a housing scholarship that allowed her to stay in<br />

dorms nearer to the college, but the scholarship provided<br />

her with only a place to sleep—not food. Sreymom’s<br />

mother there<strong>for</strong>e began sending her daughter dried meals<br />

from the village by taxi. Each carefully packed parcel fed<br />

Sreymom <strong>for</strong> a week. As if her new surroundings weren’t<br />

<strong>for</strong>eign enough, Sreymom applied three months later <strong>for</strong><br />

still another scholarship, one that took her even farther<br />

away from the life she knew—to a <strong>for</strong>eign country she had<br />

never envisioned visiting, much less spending the next six<br />

years. All this <strong>for</strong> an education most in her village believed<br />

would be wasted on a girl.<br />

Slightly over five feet tall, Sreymom seems younger and<br />

more innocent than her 18 years. Her jolly disposition is<br />

masked in a demure, even doleful demeanor, yet it takes<br />

only one conversation, one burst of contagious laughter,<br />

<strong>for</strong> the façade to crumble. Her face cracks a smile, and<br />

like sunshine melting shadows, she is trans<strong>for</strong>med. Her<br />

full, baby cheeks grow rounder, her button nose wrinkles,<br />

and her eyes crease with laughter, all but disappearing in<br />

the mirth of the moment.<br />

As a child, Sreymom lived along with her three sisters and<br />

brother, parents, and grandparents, in a small house in a<br />

small village. The village had a market where Sreymom’s<br />

mother supported her family selling goods. Her father<br />

worked as a teacher. The family separated from her grandparents<br />

when Sreymom was five, her parents moving their<br />

children to a bigger village with more opportunities. Like<br />

their <strong>for</strong>mer home, this village also consisted of simple<br />

wooden houses, but a thriving market and busy roads<br />

reflected a growing population. Most of the villagers<br />

made a living in agriculture, working as either rice or<br />

watermelon farmers. After the move, Sreymom’s mother<br />

stopped working in the market and instead sold rice out<br />

of a small shop in front of their home, giving her more<br />

time to take care of the children. Sreymom’s father abandoned<br />

his teaching career to become a musician, traveling<br />

over thirty kilometers every night by motorcycle to play<br />

organ in the Kampong Thom province. Growing up,<br />

Sreymom was very close to her father, who constantly bolstered<br />

her through many ups and downs in school. She<br />

describes him as “full of love and mercy.” When he died<br />

of high blood pressure in February of 2005, Sreymom was<br />

15. His death, she says, changed everything.<br />

The morning Sreymom’s father died, he told her: “You are<br />

big enough so you can promise me that you won’t make<br />

someone worry about you, especially your mom.” Those<br />

were his last words to her. After he died, Sreymom admits<br />

she no longer wanted to study. “My father always encourage<br />

me so I just try, try, try,” she recalls. “But when he<br />

died, no one want to see my future, why [would] I try?”<br />

It was a difficult time <strong>for</strong> the Pol family. People in the<br />

village gossiped about Sreymom’s mother, speculating<br />

she wouldn’t be able to feed her five children. They<br />

predicted that “everything would be down, down in my<br />

family,” Sreymom says, because a family with only one<br />

son faced a bleak future. “They looked down on my<br />

mother. They [always] look down on the family that has<br />

a lot of daughters.”<br />

Both food and money were scarce as Sreymom’s mother<br />

scrambled to feed her children with her meager earnings<br />

from the store in front of their home. After Sreymom saw<br />

how hard her mother had to work to put that day’s meal<br />

on the table, she recalled her father’s last words and<br />

resolved to ease her mother’s worries. The villagers’<br />

16

digs fell on her ears like sharp hail;<br />

they also drove her to act. “I think I<br />

will make her feel happiness,” she<br />

decided. “I will do my good future<br />

<strong>for</strong> her.”<br />

Sreymom excelled in school, earning<br />

her government scholarship <strong>for</strong> college<br />

in Phnom Penh in 2007 and<br />

then a place at the <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>University</strong><br />

<strong>for</strong> <strong>Women</strong>. Her mother was proud<br />

of her daughter’s acceptance at an<br />

international university, recognizing it<br />

as a rare opportunity to get “high<br />

knowledge abroad.” She was also<br />

terrified at the prospect of sending<br />

her youngest to a poor, strange<br />

country characterized by natural disasters.<br />

Sreymom’s relatives fretted as<br />

well—her aunt in<strong>for</strong>med her that all<br />

Muslim men would be rapists.<br />

Sreymom herself feared that <strong>AUW</strong>’s<br />

unusual mix of diverse religions<br />

might interfere with her own belief in<br />

Buddhism.<br />

Sreymom ultimately accepted her<br />

offer from <strong>AUW</strong> and now lives in a<br />

room with four other girls from countries<br />

all across Asia. She has since<br />

been intimately exposed to a melting<br />

pot of cultures and religions—her<br />

recent 18th birthday illustrates the<br />

trans<strong>for</strong>mation. The day had passed<br />

rather uneventfully. It was nearing<br />

midnight and Sreymom was lying in<br />

bed in her dorm room, miserable<br />

and homesick. She yearned <strong>for</strong> her<br />

mother and the birthday celebrations<br />

of her childhood, surrounded by<br />

loved ones and village friends. When<br />

she heard knocking at the door she<br />

feigned sleep, too depressed to face<br />

visitors. Her roommates barged in<br />

anyway and dragged her downstairs<br />

to a darkened classroom. The room<br />

suddenly erupted with light, and<br />

Sreymom was dazzled by a chorus of<br />

classmates serenading her with an<br />

English version of Happy Birthday.<br />

The group represented all sorts of<br />

<strong>Asian</strong> cultures and beliefs, a mixture<br />

of Sri Lankans, Bangladeshis,<br />

Nepalese, and Cambodians.<br />

Sreymom glows as she recounts<br />

the story, saying, “I’m really surprised.<br />

I think all of them are really good<br />

<strong>for</strong> me.”<br />

Although she still struggles with<br />

homesickness, and her mother still<br />

worries about her in a <strong>for</strong>eign country,<br />

Sreymom has made a place <strong>for</strong><br />

herself at <strong>AUW</strong>. Now, when her<br />

mother calls, she says laughing, “I<br />

just tell her than I’m fatter than<br />

be<strong>for</strong>e.” She also extols <strong>AUW</strong>’s academic<br />

demand. “Even the small<br />

things we need to think about,” she<br />

notes a bit begrudgingly, reminding<br />

us that even the best and the brightest<br />

can occasionally still sound like<br />

typical teenagers. Sreymom plans to<br />

use her degree to become a chemistry<br />

engineer and work in public<br />

health. She wants to provide clean<br />

water to people in her country; when<br />

she was growing up, many people in<br />

her village had to resort to pond<br />

water.<br />

But perhaps the most valuable<br />

aspect of being at <strong>AUW</strong> <strong>for</strong> Sreymom<br />

has been defying expectation. She<br />

explains, “My mother always said she<br />

didn’t have anything to give me. She<br />

had no money, nothing; she just<br />

found money <strong>for</strong> one day at a time.<br />

‘So you must try yourself,’ [she said].”<br />

As a student at <strong>AUW</strong>, every day she<br />

works to stay true to her father’s<br />

words. Furthermore, she has dealt a<br />

resounding blow to the predictions<br />

of her gossiping neighbors: “They<br />

think the women can’t do anything—<br />

they just stay at home, do a little<br />

thing to earn some money. It’s not<br />

like the son; daughters can’t earn<br />

money far away and support the<br />

home.” She pauses and her rounded<br />

face dawns with wonder: “I have<br />

destroyed that thought.”<br />

“[My neighbors]<br />

think women<br />

can’t do anything<br />

– they just<br />

stay at home,<br />

do a little thing<br />

to earn some<br />

money. It’s not<br />

like the son;<br />

daughters can’t<br />

earn money<br />

far away and<br />

support the<br />

home… I have<br />

destroyed that<br />

thought.”<br />

17

Sunita Basnet<br />

Age: 22<br />

Home Country: Nepal<br />

The first time I met Sunita Basnet, she was calmly picking<br />

a cockroach’s carcass off the floor as girls around her<br />

shrieked and fled <strong>for</strong> higher places. The offending insect<br />

had appeared moments be<strong>for</strong>e, dissolving a room full of<br />

young women—otherwise rational and capable beings—<br />

into near-hysterics, as only the enlarged, winged,<br />

Bangladeshi breed of cockroach can do. Without a<br />

moment’s hesitation, Sunita had walked right up to the<br />

bug and with a loud crunch, squelched it beneath her<br />

sandal. She proceeded to scoop up the juicy remains and<br />

saunter past us, waving crushed tentacles in front of our<br />

faces with a smirk as we crowded out of her way. Her look<br />

said it all. “You bunch of city girls,” she seemed to be<br />

saying, “This is nothing.”<br />

Sunita grew up in a remote village of about five hundred<br />

people in the Tarai area of Nepal, north of the capital. She<br />

is the eldest of five sisters and one brother; she and her<br />

five siblings live with their parents and grandmother in<br />

one house. Although no longer working, her father used<br />

to support his large family as a farmer. They live on a small<br />

plot of land that yields just enough crops to feed the nine<br />

of them. Sunita’s mother had very little schooling as a<br />

child, but Sunita and her father taught her to read and<br />

write well enough to understand most newspaper articles<br />

and sign her name. Sunita’s mother is far from atypical;<br />

most people in the village, especially the girls, are poorly<br />

educated, proof of Nepal’s struggling education system.<br />

The boys in Sunita’s village generally fare only slightly<br />

better than the girls, financial necessity <strong>for</strong>cing most to<br />

abandon their studies and work in the fields alongside<br />

their fathers. A 2<strong>001</strong> census found that just 48% of the<br />

total population had achieved literacy: 62% of Nepalese<br />

men and 34% of Nepalese women. 1<br />

Sunita’s father, however, has always valued the importance<br />

of education. On the first day of kindergarten <strong>for</strong> example,<br />

when Sunita was in the throes of a temper tantrum and<br />

refusing to leave the house, he persuaded her to go by<br />

promising that at this particular school, teachers always<br />

gave their students chocolate. With such a prize on the<br />

horizon, the usually headstrong Sunita was easily pacified.<br />

Dressed in her best, she struck out <strong>for</strong> the school, only to<br />

lose her balance and slip and fall in the mud. Her chalkboard<br />

and chalk, assigned to all school children in lieu<br />

of scarce pencil and paper, were ruined, and so was her<br />

dress. The day just went downhill from there. She arrived<br />

late with shattered pieces of chalk in hand and mud caking<br />

her front. The school lacked facilities like walls and<br />

benches so the children sat on the floor to learn their<br />

ABC’s, but Sunita’s father had already taught her the<br />

alphabet and she could only focus on one thing: chocolate.<br />

She began to demand the teachers <strong>for</strong> what she felt<br />

was rightfully hers. One teacher finally lost patience with<br />

her insistent questioning and slapped her. Indignant,<br />

Sunita hid her chalkboard under her skirt and feigned a<br />

trip to the toilets, (a nearby pond), be<strong>for</strong>e running the<br />

entire distance home. Even at five, Sunita knew how to<br />

stand her ground.<br />

Luckily, she came back. In 2004, Sunita was the first girl in<br />

her village to graduate from grade twelve. Not one to be<br />

cowed by harsh odds, social norms, or even the continual<br />

injustice of the chocolate missing from her life, Sunita’s<br />

mind quickly moved to the next challenge—raising the<br />