Children and Women in Tanzania - Unicef

Children and Women in Tanzania - Unicef

Children and Women in Tanzania - Unicef

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

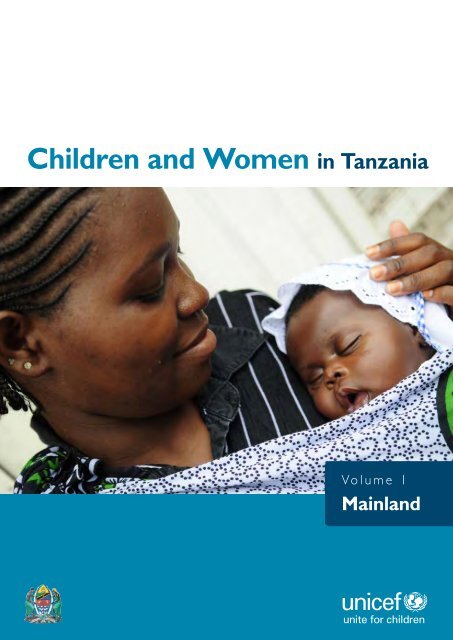

<strong>Children</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Women</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong><br />

Volume 1<br />

Ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong><br />

i

© UNICEF/Julie Pudlowski<br />

Credits<br />

Layout <strong>and</strong> Design: Julie Pudlowski Consult<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Cover Photo: UNICEF/Julie Pudlowski<br />

ii

<strong>Children</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Women</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong><br />

Volume 1 Ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong>

© UNICEF/Julie Pudlowski<br />

Ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong><br />

iv

Foreword<br />

“A <strong>Tanzania</strong>n who is born today will be fully grown up, will have jo<strong>in</strong>ed the work<strong>in</strong>g<br />

population <strong>and</strong> will probably be a young parent by the year 2025... What k<strong>in</strong>d of society<br />

will have been created by such <strong>Tanzania</strong>ns <strong>in</strong> the year 2025? What is envisioned is that<br />

the society these <strong>Tanzania</strong>ns will be liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> by then will be a substantially developed one<br />

with a high quality livelihood. Abject poverty will be a th<strong>in</strong>g of the past... <strong>Tanzania</strong>ns will<br />

have graduated from a least developed country to a middle <strong>in</strong>come country with a high<br />

level of human development.”<br />

These words, enshr<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Tanzania</strong> Development Vision 2025, resonate today with the<br />

same vigour <strong>and</strong> urgency as when they were written <strong>in</strong> 2000. This report, the result of a jo<strong>in</strong>t<br />

collaboration between the Government of the United Republic of <strong>Tanzania</strong> <strong>and</strong> the United<br />

Nations <strong>Children</strong>’s Fund, argues that the vision of an economically prosperous <strong>Tanzania</strong> can only<br />

be realised if the survival, well-be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> development of its children is assured. Indeed, every<br />

country that has made the breakthrough to middle-<strong>in</strong>come status has <strong>in</strong>vested heavily <strong>in</strong> children.<br />

Their development is the s<strong>in</strong>gle most important driver of national growth.<br />

<strong>Children</strong> also represent the foundation of a vibrant democracy <strong>and</strong> a cohesive, peaceful society.<br />

The first cohorts of children to benefit from the Primary Education Development Plan voted<br />

<strong>in</strong> national elections <strong>in</strong> 2010, while students leav<strong>in</strong>g primary school this year will be eligible to<br />

vote <strong>in</strong> 2015, the target date for the Millennium Development Goals. Young people need to be<br />

supported to grow up as <strong>in</strong>formed <strong>and</strong> empowered citizens. Healthy, educated children also<br />

become creative, productive adults. S<strong>in</strong>ce children make up over half the country’s population,<br />

it is not some distant future that is at stake. Invest<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> their well-be<strong>in</strong>g now is the soundest<br />

<strong>in</strong>vestment <strong>Tanzania</strong> can make to secure economic, social <strong>and</strong> political stability <strong>and</strong> prosperity.<br />

© UNICEF/Julie Pudlowski<br />

This report highlights areas where progress has been made <strong>in</strong> secur<strong>in</strong>g the rights of children <strong>and</strong><br />

women, <strong>and</strong> identifies where progress has stalled or is lagg<strong>in</strong>g beh<strong>in</strong>d. It sheds light on policies<br />

<strong>and</strong> strategies that have worked <strong>and</strong> those <strong>in</strong> need of adjustment. Undoubtedly, <strong>Tanzania</strong> has<br />

seen major progress <strong>in</strong> child health <strong>and</strong> education, as well as <strong>in</strong> some aspects of HIV <strong>and</strong> AIDS.<br />

Such progress, however, has often been uneven, <strong>and</strong> must not detract from the fact that other<br />

areas of critical relevance to children <strong>and</strong> women have received less attention from policy makers,<br />

particularly maternal <strong>and</strong> newborn healthcare, nutrition, social <strong>and</strong> child protection, disability<br />

<strong>and</strong>, until recently, early childhood development <strong>and</strong> water, hygiene <strong>and</strong> sanitation.<br />

In the quest for accelerat<strong>in</strong>g progress <strong>in</strong> meet<strong>in</strong>g the rights of <strong>Tanzania</strong>n children <strong>and</strong> women,<br />

the question of what ought to be done first does not lend itself to easy answers. Among many<br />

compet<strong>in</strong>g dem<strong>and</strong>s, <strong>Tanzania</strong> will need to set clear priorities, tak<strong>in</strong>g account of the capacity to<br />

deliver on them. A judicious mix of realism <strong>and</strong> ambition will be required. Even though rights<br />

are <strong>in</strong>divisible <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>terdependent, not every issue can be tackled at once. In a context of scarce<br />

resources, the fulfilment of rights dem<strong>and</strong>s mak<strong>in</strong>g policy choices with a clear m<strong>in</strong>dset, <strong>and</strong><br />

del<strong>in</strong>eat<strong>in</strong>g a critical path for their progressive realization.<br />

We are confident that the analysis <strong>and</strong> f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs of this report, along with the <strong>Children</strong>’s Agenda it<br />

del<strong>in</strong>eates, will help <strong>in</strong>form the discussions <strong>and</strong> sett<strong>in</strong>g of priorities for the fulfilment of the rights<br />

of all <strong>Tanzania</strong>n children <strong>and</strong> of the vision of a strong <strong>and</strong> prosperous country. Twenty million<br />

children <strong>and</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> can ill afford to wait.<br />

Ramadhan Khijjah<br />

Permanent Secretary<br />

M<strong>in</strong>istry of F<strong>in</strong>ance<br />

Dorothy Rozga<br />

Representative<br />

UNICEF <strong>Tanzania</strong><br />

v

© UNICEF/Julie Pudlowski<br />

vi

Acknowledgements<br />

The report on <strong>Children</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Women</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> 2010 is the result of a jo<strong>in</strong>t collaboration between<br />

the Government of the United Republic of <strong>Tanzania</strong> <strong>and</strong> UNICEF. Given its breadth <strong>and</strong> scope, the<br />

report would not have been possible without the strong commitment, guidance <strong>and</strong> support of<br />

the members of the National Steer<strong>in</strong>g Committee set up <strong>in</strong> 2009 to advise, oversee <strong>and</strong> validate<br />

the results of the analysis, the f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>and</strong> the recommendations conta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> this publication.<br />

Chaired by the M<strong>in</strong>istry of F<strong>in</strong>ance <strong>and</strong> Economic Affairs <strong>and</strong> co-chaired by UNICEF, the Steer<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Committee had representation from a broad cross-section of M<strong>in</strong>istries, Departments <strong>and</strong><br />

Agencies, as well as civil society organisations. Special thanks are due, first <strong>and</strong> foremost, to the<br />

Government of the United Republic of <strong>Tanzania</strong> <strong>and</strong> the Revolutionary Government of Zanzibar,<br />

<strong>and</strong> also to the many participants <strong>in</strong> the stakeholder consultations held dur<strong>in</strong>g 2009 <strong>and</strong> 2010 to<br />

discuss the prelim<strong>in</strong>ary f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs from the analytical work commissioned for the publication.<br />

Among those who took part <strong>in</strong> the steer<strong>in</strong>g committee <strong>and</strong> the consultations carried out over<br />

the course of several months were representatives from the follow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>stitutions: M<strong>in</strong>istry of<br />

Agriculture <strong>and</strong> Food Security, M<strong>in</strong>istry of Community Development, Gender <strong>and</strong> <strong>Children</strong>,<br />

M<strong>in</strong>istry of Education <strong>and</strong> Vocational Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, M<strong>in</strong>istry of Health <strong>and</strong> Social Welfare, M<strong>in</strong>istry of<br />

Infrastructure Development, M<strong>in</strong>istry of Justice <strong>and</strong> Constitutional Affairs, M<strong>in</strong>istry of Labour,<br />

Employment <strong>and</strong> Youth Development, M<strong>in</strong>istry of Water <strong>and</strong> Irrigation, Plann<strong>in</strong>g Commission,<br />

Prime M<strong>in</strong>ister’s Office, Commission for Human Rights <strong>and</strong> Good Governance, National Bureau of<br />

Statistics, Office of the Chief Government Statistician, <strong>Tanzania</strong> Commission for AIDS (TACAIDS),<br />

<strong>Tanzania</strong> Social Action Fund (TASAF), <strong>Tanzania</strong> Food <strong>and</strong> Nutrition Centre (TFNC), <strong>Tanzania</strong><br />

Education Network (TEN/MET), <strong>Tanzania</strong> Federation of Disabled People’s Organizations<br />

(SHIVYAWATA), <strong>Tanzania</strong> Gender Network Programme (TGNP), <strong>Tanzania</strong> Water <strong>and</strong> Sanitation<br />

Network (TAWASANET), <strong>Tanzania</strong> <strong>Women</strong> Lawyers’ Association, CCBRT, Christian Social<br />

Services Commission, Family Health International, Ifakara Health Institute, PACT International,<br />

Save the <strong>Children</strong>, SNV, UK Department for International Development (DfID), UNAIDS, UNFPA,<br />

USAID, WaterAid, Youth Action Volunteers <strong>and</strong> Youth Peer Education Network.<br />

© UNICEF/Julie Pudlowski<br />

Background papers for the publication were produced by Paul Smithson (chapter 2), John Msuya<br />

(chapter 3), Ben Taylor (chapter 4), Suleman Sumra (chapter 5), Halima Shariff <strong>and</strong> Rugola Mt<strong>and</strong>u<br />

(chapter 6), <strong>and</strong> Andrew Dunn <strong>and</strong> Robert Mhamba (chapter 7). Kate McAlp<strong>in</strong>e contributed a<br />

prelim<strong>in</strong>ary version of the executive summary <strong>and</strong> the <strong>in</strong>troductory chapter, <strong>and</strong> also provided<br />

detailed comments <strong>and</strong> helped revise all the chapters <strong>in</strong> the report. Chapter 8 is the outcome of<br />

broad consultations with a range of stakeholders from Government, lead<strong>in</strong>g children’s organisations<br />

<strong>and</strong> children from across the country. Chris Daly proof read <strong>and</strong> edited the full report.<br />

Every section of the UNICEF Office was <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> the preparation of the report. Contributions<br />

are duly acknowledged from Young Child Survival <strong>and</strong> Development (chapters 2, 3 <strong>and</strong> 4), Basic<br />

Education <strong>and</strong> Life Skills (chapter 5), HIV <strong>and</strong> AIDS (chapter 6), Child Protection <strong>and</strong> Participation<br />

(chapter 7) <strong>and</strong> Communication <strong>and</strong> Partnerships (chapter 8). Policy Advocacy <strong>and</strong> Analysis<br />

was responsible for the overall coord<strong>in</strong>ation, quality assurance <strong>and</strong> distillation of the key f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

<strong>and</strong> recommendations of the report. For cont<strong>in</strong>uous support as well as the provision of specific<br />

<strong>in</strong>puts, special thanks are also given to the Office of the Deputy Representative, the Operations<br />

<strong>and</strong> Plann<strong>in</strong>g sections, the Emergency Preparedness <strong>and</strong> Response division <strong>and</strong> the Zanzibar<br />

sub-Office of UNICEF.<br />

Given the wide range of contributions <strong>in</strong>to this publication, its contents <strong>and</strong> conclusions may<br />

not necessarily reflect the views of every one of the contributors or the <strong>in</strong>stitutions they<br />

represent.<br />

vii

© UNICEF/Julie Pudlowski<br />

viii

Table of Contents<br />

Foreword<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

List of Tables<br />

List of Figures<br />

List of Acronyms<br />

Overview 1<br />

Introduction 13<br />

Chapter 1: Establish<strong>in</strong>g a foundation for child rights <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> 21<br />

1.1 The national context for the realisation of child rights 21<br />

1.2 Child-sensitive social protection 23<br />

1.3 What is <strong>in</strong> the best <strong>in</strong>terests of <strong>Tanzania</strong>n children? 27<br />

1.3.1 <strong>Children</strong>’s experience of family 27<br />

1.3.2 Political <strong>and</strong> societal attitudes towards children 28<br />

Chapter 2: Maternal health <strong>and</strong> child survival 31<br />

2.1 Status <strong>and</strong> trends 31<br />

2.1.1 Maternal health: The foundation of child survival <strong>and</strong> well-be<strong>in</strong>g 31<br />

2.1.2 Child survival <strong>and</strong> well-be<strong>in</strong>g 37<br />

2.2 Human resources 48<br />

2.3 Key strategies affect<strong>in</strong>g maternal <strong>and</strong> child health 49<br />

2.3.1 Sector-wide strategies <strong>in</strong> health 49<br />

2.3.2 Sub-sector strategies 50<br />

2.3.3 Challenges <strong>in</strong> health sector reform 52<br />

2.4 Health f<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g 53<br />

2.4.1 User fees 53<br />

2.4.2 Health sector <strong>in</strong>come <strong>and</strong> expenditure 53<br />

2.5 Institutional frameworks <strong>in</strong> the health sector 54<br />

2.5.1 Sector-wide approach <strong>in</strong> health 54<br />

2.5.2 Decentralisation 54<br />

2.5.3 Community participation 54<br />

2.5.4 Public-private partnerships 55<br />

2.6 Priority areas <strong>and</strong> recommendations 56<br />

Chapter 3: Nutrition 59<br />

3.1 Conceptual framework for analys<strong>in</strong>g malnutrition 59<br />

3.2 Status <strong>and</strong> trends 62<br />

3.2.1 Nutrition status of women 62<br />

3.2.2 Nutrition status of children 63<br />

3.3 Feed<strong>in</strong>g practices for children 70<br />

3.4 Key strategies <strong>and</strong> fiscal space 72<br />

3.5 Institutional frameworks 73<br />

3.6 Priority areas <strong>and</strong> recommendations 76<br />

Chapter 4: Water, sanitation <strong>and</strong> hygiene 79<br />

4.1 Status <strong>and</strong> trends 80<br />

4.1.1 Water supply 80<br />

4.1.2 Household sanitation 83<br />

v<br />

vii<br />

xiii<br />

xiv<br />

xvii<br />

© UNICEF/Julie Pudlowski<br />

ix

<strong>Children</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Women</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong><br />

4.1.3 Water, sanitation <strong>and</strong> hygiene for vulnerable groups 85<br />

4.1.4 Water, sanitation <strong>and</strong> hygiene <strong>in</strong> schools 86<br />

4.1.5 Water, sanitation <strong>and</strong> hygiene <strong>in</strong> health facilities 88<br />

4.1.6 Health outcomes 88<br />

4.2 Promotion of hygienic practices 90<br />

4.2.1 H<strong>and</strong> wash<strong>in</strong>g 90<br />

4.2.2 Disposal of children’s stools 91<br />

4.3 Key policies <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutions 92<br />

4.3.1 Water 92<br />

4.3.2 Sanitation <strong>and</strong> hygiene 92<br />

4.3.3 Institutional capacity, monitor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> accountability 93<br />

4.4 Fiscal space 95<br />

4.4.1 Water 95<br />

4.4.2 Sanitation <strong>and</strong> hygiene 96<br />

4.4.3 The political prioritisation of water, sanitation <strong>and</strong> hygiene 97<br />

4.5 Priority areas <strong>and</strong> recommendations 99<br />

4.5.1 Water supply 99<br />

4.5.2 Sanitation <strong>and</strong> hygiene 100<br />

Chapter 5: Education 103<br />

5.1 Conceptual framework 103<br />

5.2 Adult literacy 108<br />

5.3 Status <strong>and</strong> trends <strong>in</strong> children’s education 108<br />

5.3.1 Access to education 108<br />

5.3.2 The quality of pre-primary <strong>and</strong> primary education 114<br />

5.4 Factors affect<strong>in</strong>g learn<strong>in</strong>g outcomes 115<br />

5.4.1 Gender 115<br />

5.4.2 <strong>Children</strong> on the marg<strong>in</strong>s 116<br />

5.4.3 The school environment 119<br />

5.4.4 Teachers 123<br />

5.4.5 St<strong>and</strong>ards <strong>and</strong> quality assurance 126<br />

5.5 Fiscal space 127<br />

5.6 Institutional frameworks 129<br />

5.6.1 Decentralisation by devolution 129<br />

5.6.2 Sector dialogue <strong>and</strong> participation 131<br />

5.7 Priority areas <strong>and</strong> recommendations 131<br />

Chapter 6: <strong>Women</strong>, children <strong>and</strong> HIV <strong>and</strong> AIDS 135<br />

6.1 Overview of the HIV epidemic <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> 135<br />

6.2 Gender, poverty <strong>and</strong> HIV <strong>and</strong> AIDS 136<br />

6.3 Key strategies: Status of the national response to HIV <strong>and</strong> AIDS 137<br />

6.3.1 Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV 140<br />

6.3.2 Care <strong>and</strong> treatment services 142<br />

6.4 Key <strong>in</strong>terventions to prevent HIV transmission among women <strong>and</strong> children 144<br />

6.4.1 Primary prevention 144<br />

6.4.2 Reduc<strong>in</strong>g risky behaviours 145<br />

x

Table of Contents<br />

6.5 Fiscal space 148<br />

6.6 Institutional frameworks <strong>and</strong> monitor<strong>in</strong>g systems 149<br />

6.7 Priority areas <strong>and</strong> recommendations 150<br />

Chapter 7: Protection of children aga<strong>in</strong>st abuse, neglect <strong>and</strong> exploitation 153<br />

7.1 International <strong>in</strong>struments <strong>and</strong> domestic laws <strong>and</strong> targets for child protection 153<br />

7.1.1 International <strong>in</strong>struments on child protection 153<br />

7.1.2 The Law of the Child Act 2009 <strong>and</strong> other significant national laws 155<br />

7.1.3 Domestic targets for child protection 156<br />

7.2 A conceptual framework for child protection 156<br />

7.3 Status <strong>and</strong> trends <strong>in</strong> child protection 157<br />

7.3.1 Birth registration 157<br />

7.3.2 Child labour 159<br />

7.3.3 Child migration, traffick<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> children liv<strong>in</strong>g on the streets 160<br />

7.3.4 <strong>Children</strong> <strong>in</strong> conflict with the law 160<br />

7.4 Societal attitudes <strong>and</strong> behaviours that put children at risk 162<br />

7.4.1 Gender-based violence 163<br />

7.5 The National Costed Plan for most vulnerable children 165<br />

7.6 Institutional frameworks for deliver<strong>in</strong>g child protection services 167<br />

7.7 Current responses to priority child protection concerns 168<br />

7.7.1 Interventions to elim<strong>in</strong>ate child labour <strong>and</strong> sexual exploitation 168<br />

7.7.2 Legal frameworks <strong>and</strong> services to protect children with disabilities 169<br />

7.7.3 Childcare services <strong>and</strong> provision of alternative care 169<br />

7.8 Fiscal space for child protection 171<br />

7.9 Priority areas <strong>and</strong> recommendations for child protection 173<br />

Chapter 8: The <strong>Children</strong>’s Agenda 177<br />

01. Invest to save the lives of women <strong>and</strong> children 177<br />

02. Invest <strong>in</strong> good nutrition 178<br />

03. Invest <strong>in</strong> safe water, better hygiene <strong>and</strong> sanitation <strong>in</strong> schools <strong>and</strong> health facilities 180<br />

04. Invest <strong>in</strong> early childhood development 181<br />

05. Invest <strong>in</strong> quality education for all children 182<br />

06. Invest to make schools safe 183<br />

07. Invest to protect <strong>in</strong>fants <strong>and</strong> adolescent girls from HIV 185<br />

08. Invest to reduce teenage pregnancy 186<br />

09. Invest to protect children from violence, abuse <strong>and</strong> exploitation 187<br />

10. Invest <strong>in</strong> children with disabilities 188<br />

Empower<strong>in</strong>g families to care for children: A universal system of social protection 190<br />

References 193<br />

xi

© UNICEF/Julie Pudlowski<br />

xii

List of Tables<br />

Table 1: Fast Facts: <strong>Tanzania</strong>n demographics 22<br />

Table 2: MKUKUTA targets for health 33<br />

Table 3: Place of delivery (rural only) <strong>and</strong> proportion of (all) facilities able<br />

to offer quality obstetric care 34<br />

Table 4: Achievements of the pilot ECD home-based care programme<br />

<strong>in</strong> Kibaha district between 2003 <strong>and</strong> 2007 39<br />

Table 5: MKUKUTA <strong>and</strong> MDG targets for nutrition 59<br />

Table 6: MKUKUTA <strong>and</strong> MDG targets on water, sanitation <strong>and</strong> hygiene 79<br />

Table 7: Recent trends <strong>in</strong> water <strong>in</strong>frastructure 81<br />

Table 8: Access to improved water supplies, by household type <strong>and</strong> residence 82<br />

Table 9: Availability of WASH at health facilities, <strong>in</strong> percentages 88<br />

© UNICEF/Julie Pudlowski<br />

Table 10: Cumulative reported cholera cases <strong>and</strong> deaths by region, 1999-2008 89<br />

Table 11: Economic return on <strong>in</strong>vestment <strong>in</strong> WASH <strong>in</strong> East Africa 97<br />

Table 12: Fast Facts: Progress aga<strong>in</strong>st MDGs, Education for All<br />

<strong>and</strong> MKUKUTA targets 107<br />

Table 13: MKUKUTA targets <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>dicators relat<strong>in</strong>g to HIV <strong>and</strong> AIDS 139<br />

Table 14: Knowledge <strong>and</strong> condom use among young people 146<br />

Table 15: Public <strong>and</strong> donor expenditure on HIV <strong>and</strong> AIDS, by fund<strong>in</strong>g<br />

mechanisms (TSh billions) 149<br />

Table 16: Specific targets for child protection under MKUKUTA 157<br />

Table 17: Adoption data from the Social Welfare Department 171<br />

Table 18: Actual Requirements vs Funds Released for Other Charges<br />

<strong>and</strong> Development Budget 2006/07 - 2008/09 172<br />

xiii

List of Figures<br />

Figure 1: Relationship between child rights <strong>and</strong> development 15<br />

Figure 2: Child rights <strong>and</strong> the role of duty bearers 16<br />

Figure 3: The child’s life course 18<br />

Figure 4: Social protection <strong>in</strong> MKUKUTA I <strong>and</strong> II 25<br />

Figure 5: The child’s life course: Health needs for survival <strong>and</strong> well-be<strong>in</strong>g 32<br />

Figure 6: Skilled attendance at delivery by wealth <strong>and</strong> residence 34<br />

Figure 7: Indicators of women’s low socio-economic status <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>, by age group 36<br />

Figure 8: Under-five mortality targets <strong>and</strong> actual trajectory 37<br />

Figure 9: Components of under-five mortality: 1999-2007/8 37<br />

Figure 10: Components of <strong>in</strong>tegrated early childhood development 38<br />

Figure 11: The child’s life course: The early years 41<br />

Figure 12: Lead<strong>in</strong>g causes of neonatal mortality 42<br />

Figure 13: Geographic disparities <strong>in</strong> under-five mortality 43<br />

Figure 14: Lead<strong>in</strong>g causes of illness, 2007: children 0-15 years 44<br />

Figure 15: Trends <strong>in</strong> childhood illness 44<br />

Figure 16: Trends <strong>in</strong> coverage of bed nets 45<br />

Figure 17: Prevalence of malaria parasitaemia <strong>in</strong> children aged 6-59 months; 2007/8 46<br />

Figure 18: DPT-Hb3 vacc<strong>in</strong>ation coverage, 2001-2008 47<br />

Figure 19: Health worker distribution per 10,000 population, 2008 48<br />

Figure 20: Conceptual framework of causes of malnutrition 60<br />

Figure 21: Life-cycle of malnutrition 61<br />

Figure 22: Low birth weight trend, <strong>in</strong> the five years prior to survey 64<br />

Figure 23: Under-five nutrition trends <strong>and</strong> targets 65<br />

Figure 24: Under-five stunt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> underweight trends disaggregated by urban / rural 65<br />

Figure 25: Malnutrition by age, 2004/5 66<br />

Figure 26: Malnutrition by household wealth, 2004/5 66<br />

Figure 27: Severe anaemia <strong>in</strong> under-fives by age (months) <strong>and</strong> residence,<br />

2004/5 <strong>and</strong> 2007/8 67<br />

Figure 28: Prevalence of severe anaemia <strong>in</strong> children 6-59 months, 2007/8 68<br />

Figure 29: Percentage of under-fives sick <strong>in</strong> the last two weeks<br />

by anaemia status, 2004/5 69<br />

Figure 30: Proportion of children exclusively breastfed by age (0-6 months) 71<br />

Figure 31: Percentage of under-fives stunted by age, 1999-2004/5 71<br />

Figure 32: Proportion of households us<strong>in</strong>g an improved source as ma<strong>in</strong> source<br />

of dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water 80<br />

xiv

Figure 33: Water access (2002) <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>frastructure (2008), by district 81<br />

Figure 34: Access to water by residence <strong>and</strong> poverty status, 2004/5 82<br />

Figure 35: Mean expenditure on water per month, by <strong>in</strong>come group 83<br />

Figure 36: Household latr<strong>in</strong>e coverage, 2002-2007 84<br />

Figure 37: Rural households not us<strong>in</strong>g any toilet facility, 2002 84<br />

Figure 38: Latr<strong>in</strong>e access by household wealth, 2004/5 85<br />

Figure 39: School latr<strong>in</strong>e coverage trends <strong>and</strong> targets 86<br />

Figure 40: School pit latr<strong>in</strong>es by year of construction, Bagamoyo district 87<br />

Figure 41: Cholera <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> 88<br />

Figure 42: Diarrhoea <strong>in</strong> children under five years, <strong>in</strong> percentages 90<br />

Figure 43: H<strong>and</strong>-wash<strong>in</strong>g practices 91<br />

© UNICEF/Giacomo Pirozzi<br />

Figure 44: Safe disposal of children’s stools 91<br />

Figure 45: Water sector budgets, 2001-2009 95<br />

Figure 46: Budget allocations to rural water supply, 2005/6 <strong>and</strong> 20089 95<br />

Figure 47: Cost-effectiveness of sanitation <strong>and</strong> hygiene promotion compared<br />

with other health <strong>in</strong>terventions 97<br />

Figure 48: Priority issues for rural <strong>Tanzania</strong>ns 98<br />

Figure 49: Citizens’ satisfaction with Government efforts <strong>in</strong> key sectors 98<br />

Figure 50: The child’s life course: Education 104<br />

Figure 51: Correlations between regional per capita <strong>in</strong>come <strong>and</strong> pupil-teacher ratio 106<br />

Figure 52: Correlation between regional per capita <strong>in</strong>come <strong>and</strong> students’<br />

performance <strong>in</strong> the Primary School Leavers Exam 106<br />

Figure 53: Adult literacy rate by residence, 2000/01 <strong>and</strong> 2007 108<br />

Figure 54: Pre-primary enrolment, Ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>, 2004-2009 109<br />

Figure 55: Pupils enrolled <strong>in</strong> primary schools, Ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>, 2001–2009 110<br />

Figure 56: Pupils enrolled <strong>in</strong> St<strong>and</strong>ard I, Ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>, 2001–2009 110<br />

Figure 57: Gross <strong>and</strong> Net Enrolment Ratios <strong>in</strong> primary schools by region,<br />

Ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>, 2009 111<br />

Figure 58: Students enrolled <strong>in</strong> secondary schools, Ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>, 2001-2009 111<br />

Figure 59: Net Enrolment Ratio <strong>in</strong> secondary education, Ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>, 2005 -2009 112<br />

Figure 60: Primary School Leav<strong>in</strong>g Exam<strong>in</strong>ation results, Ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>, 2000 - 2008 115<br />

Figure 61: Gender <strong>and</strong> exclusion of girls from education, Ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>, 2008 117<br />

Figure 62: Percentage of children with disabilities <strong>in</strong> primary school, by grade,<br />

Ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>, 2009 (% of total enrolments) 119<br />

xv

<strong>Children</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Women</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong><br />

Figure 63: Pupil-teacher ratio <strong>in</strong> primary schools, Ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>, 2000-2009 123<br />

Figure 64: Pupil-teacher ratio by region, 2009 124<br />

Figure 65: Variations <strong>in</strong> pupil-teacher ratio <strong>in</strong> selected districts,<br />

Ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>, 2006 124<br />

Figure 66: Estimate of actual expenditures on public education, 2008/09 (Tsh billions) 126<br />

Figure 67: Approved education budget as a percentage of GDP <strong>and</strong> as a percentage<br />

of the total government budget, 2001/02 – 2007/08 127<br />

Figure 68: Public education expenditure by sub-sector,<br />

Ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>, 2002/3-2007/8 128<br />

Figure 69: Prevalence of HIV <strong>in</strong> Ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> Regions, 2007-08 136<br />

Figure 70: Trends <strong>in</strong> HIV prevalence, 2003-2008 136<br />

Figure 71: Causality framework of HIV <strong>and</strong> AIDS <strong>in</strong> women <strong>and</strong> children <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> 138<br />

Figure 72: PMTCT Programme performance, 2005-2008 140<br />

Figure 73: Distribution of women who tested HIV+ <strong>and</strong> received ARV prophylaxis<br />

<strong>and</strong> their <strong>in</strong>fants 141<br />

Figure 74: Coverage of PMTCT services by sites, 2004-2008 142<br />

Figure 75: People liv<strong>in</strong>g with HIV enrolled on ART from 2006 to July 2009 142<br />

Figure 76: <strong>Children</strong> as a proportion of CTC clients 143<br />

Figure 77: Trends <strong>in</strong> HIV prevalence by level of education 147<br />

Figure 78: Protection <strong>and</strong> the child’s life course 154<br />

Figure 79: A conceptual framework for creat<strong>in</strong>g a protective environment for children 158<br />

Figure 80: DSW budgetary allocation aga<strong>in</strong>st M<strong>in</strong>isterial budget 173<br />

xvi

List of Acronyms<br />

ACRWC<br />

AIDS<br />

AMREF<br />

ALU<br />

ANC<br />

ARI<br />

ART<br />

ARVs<br />

ART<br />

BEST<br />

BMI<br />

BWO<br />

CBO<br />

CEDAW<br />

c-IMCI<br />

CMAC<br />

COBET<br />

COWSO<br />

CRC<br />

CSO<br />

DALY<br />

D by D<br />

DHS<br />

DMS<br />

DPT-HB3<br />

DSW<br />

ECD<br />

EFA<br />

EPI<br />

EWURA<br />

ESDP<br />

FBOs<br />

FGM<br />

GAR<br />

GDP<br />

GER<br />

GoT<br />

HBS<br />

HIV<br />

HMIS<br />

HSSP III<br />

IDD<br />

IEC<br />

IHI<br />

ILO<br />

IMCI<br />

African Charter on the Rights <strong>and</strong> Welfare of the Child<br />

Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome<br />

African Medical <strong>and</strong> Research Foundation<br />

Artemether Lumefantr<strong>in</strong>e<br />

Antenatal care<br />

Acute respiratory <strong>in</strong>fection<br />

Anti-retroviral treatment<br />

Anti-retrovirals<br />

Anti-retroviral therapy<br />

Basic Education Statistics <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong><br />

Body Mass Index<br />

Bas<strong>in</strong> Water Office<br />

Community-based organisation<br />

Convention on the Elim<strong>in</strong>ation of All Forms of Discrim<strong>in</strong>ation<br />

Aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>Women</strong><br />

Community-Integrated Management of Childhood Illness<br />

Council Multi-sectoral AIDS Committee<br />

Complementary Basic Education <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong><br />

Community-owned Water Supply Authority<br />

United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child<br />

Civil society organisation<br />

Disability-adjusted life years<br />

Decentralisation by Devolution<br />

Demographic <strong>and</strong> Health Survey<br />

Data management system<br />

Diptheria, Pertussis, Tetanus <strong>and</strong> Hepatitis B vacc<strong>in</strong>e (3 doses)<br />

Department of Social Welfare<br />

Early childhood development<br />

Education for All<br />

Exp<strong>and</strong>ed Program on Immunisation<br />

Energy <strong>and</strong> Water Utilities Regulatory Authority<br />

Education Sector Development Programme<br />

Faith-based organisations<br />

Female genital mutilation<br />

Gross Attendance Ratio<br />

Gross Domestic Product<br />

Gross Enrolment Ratio<br />

Government of <strong>Tanzania</strong><br />

Household Budget Survey<br />

Human Immuno-deficiency Virus<br />

Health Management Information System<br />

Health Sector Strategic Plan III<br />

Iod<strong>in</strong>e deficiency disorders<br />

Information, education <strong>and</strong> communication<br />

Ifakara Health Institute<br />

International Labour Organisation<br />

Integrated Management of Childhood Illnesses<br />

xvii

<strong>Children</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Women</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong><br />

IMR<br />

INGO<br />

ITN<br />

IPPE<br />

IPTp<br />

JMP<br />

LBW<br />

LGA<br />

MCC<br />

MCDGC<br />

MDG<br />

MKUKUTA<br />

MKUZA<br />

MMAM<br />

MMR<br />

MNCH<br />

MoEVT<br />

MoHSW<br />

MoLEYD<br />

MoWI<br />

MVC<br />

MVCC<br />

NAR<br />

NACP<br />

NAWAPO<br />

NBS<br />

NCPA<br />

NER<br />

NGO<br />

NSGRP<br />

NMSF<br />

NSPF<br />

NWSDS<br />

ORS<br />

OVC<br />

PEDP<br />

PEPFAR<br />

PER<br />

PHDR<br />

PHAST<br />

PLWHA<br />

PMO-RALG<br />

PMTCT<br />

PO-PSM<br />

PRSP<br />

RCH<br />

Infant Mortality Rate<br />

International non-government organisation<br />

Insecticide-treated mosquito nets<br />

Integrated post-primary education<br />

Intermittent preventive treatment for malaria <strong>in</strong> pregnancy<br />

Jo<strong>in</strong>t Monitor<strong>in</strong>g Programme<br />

Low birth weight<br />

Local government authority<br />

Millennium Challenge Corporation<br />

M<strong>in</strong>istry of Community Development, Gender <strong>and</strong> <strong>Children</strong><br />

Millennium Development Goals<br />

Mkakati wa Kukuza Uchumi na Kupunguza Umask<strong>in</strong>i <strong>Tanzania</strong><br />

Mkakati wa Kukuza Uchumi Zanzibar<br />

Swahili acronym for Primary Health Services Development Strategy<br />

Maternal Mortality Ratio<br />

Maternal, newborn <strong>and</strong> child health<br />

M<strong>in</strong>istry of Education <strong>and</strong> Vocational Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

M<strong>in</strong>istry of Health <strong>and</strong> Social Welfare<br />

M<strong>in</strong>istry of Labour, Employment <strong>and</strong> Youth Development<br />

M<strong>in</strong>istry of Water <strong>and</strong> Irrigation<br />

Most vulnerable children<br />

Most Vulnerable <strong>Children</strong> Committee<br />

Net Attendance Ratio<br />

National AIDS Control Program<br />

National Water Policy<br />

National Bureau of Statistics<br />

National Costed Plan of Action for MVC<br />

Net Enrolment Ratio<br />

Non-government organisation<br />

National Strategy for Growth <strong>and</strong> Reduction of Poverty<br />

National Multi-sectoral Strategic Framework<br />

National Social Protection Framework<br />

National Water Sector Development Strategy<br />

Oral rehydration solution<br />

Orphans <strong>and</strong> vulnerable children<br />

Primary Education Development Plan<br />

President’s Emergency Preparedness Fund for AIDS Relief<br />

Public Expenditure Review<br />

Poverty <strong>and</strong> Human Development Report<br />

Participatory Hygiene <strong>and</strong> Sanitation Transformation<br />

People liv<strong>in</strong>g with HIV <strong>and</strong> AIDS<br />

Prime M<strong>in</strong>ister’s Office – Regional Adm<strong>in</strong>istration<br />

<strong>and</strong> Local Government<br />

Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV<br />

President’s Office- Public Sector Management<br />

Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper<br />

Reproductive <strong>and</strong> child health<br />

xviii

List of Acronyms<br />

RDTs<br />

REPOA<br />

RHMT<br />

SACMEQ<br />

SADC<br />

SEDP<br />

SitAn<br />

SNV<br />

SOSPA<br />

SP<br />

STI<br />

SWAp<br />

SWO<br />

TACAIDS<br />

TASAF<br />

TAWASANET<br />

TB<br />

TBA<br />

TDHS<br />

TFNC<br />

THIS<br />

THMIS<br />

TSPA<br />

Tsh<br />

TVET<br />

UNAIDS<br />

UNDAF<br />

UNDP<br />

UNESCO<br />

UNICEF<br />

URT<br />

USAID<br />

UWSA<br />

VAD<br />

VCT<br />

VIP<br />

VMAC<br />

WASH<br />

WHO<br />

WMACs<br />

WPM<br />

WRM<br />

WSDP<br />

WSP<br />

ZSGRP<br />

Rapid diagnostic tests<br />

Research on Poverty Alleviation<br />

Regional Health Management Teams<br />

Southern <strong>and</strong> East African Consortium for Monitor<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Educational Quality<br />

Southern Africa Development Community<br />

Secondary Education Development Plan<br />

Situation <strong>and</strong> trends analysis<br />

Dutch Development Agency<br />

Sexual Offences Special Provisions Act<br />

Sulfadox<strong>in</strong>e Pyremetham<strong>in</strong>e<br />

Sexually transmitted <strong>in</strong>fection<br />

Sector-wide approach<br />

Social Welfare Officer<br />

<strong>Tanzania</strong> Commission for AIDS<br />

<strong>Tanzania</strong> Social Action Fund<br />

<strong>Tanzania</strong> Water <strong>and</strong> Sanitation Network<br />

Tuberculosis<br />

Traditional birth attendant<br />

<strong>Tanzania</strong> Demographic <strong>and</strong> Health Survey<br />

<strong>Tanzania</strong> Food <strong>and</strong> Nutrition Centre<br />

<strong>Tanzania</strong> HIV/AIDS Indicator Survey<br />

<strong>Tanzania</strong> HIV/AIDS <strong>and</strong> Malaria Indicator Survey<br />

<strong>Tanzania</strong> Service Provision Assessment<br />

<strong>Tanzania</strong> shill<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

Technical vocational education <strong>and</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

Jo<strong>in</strong>t United Nations Programme on AIDS<br />

United National Development Assistance Framework<br />

United Nations Development Programme<br />

United Nations Educational, Scientific <strong>and</strong> Cultural Organisation<br />

United Nations <strong>Children</strong>’s Fund<br />

United Republic of <strong>Tanzania</strong><br />

United States Agency for International Development<br />

Urban Water Supply Authority<br />

Vitam<strong>in</strong> A deficiency<br />

Voluntary counsell<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> test<strong>in</strong>g for HIV<br />

Ventilated improved pit (latr<strong>in</strong>e)<br />

Village Multi-sectoral AIDS Committee<br />

Water, sanitation <strong>and</strong> hygiene<br />

World Health Organisation<br />

Ward Multi-sectoral AIDS Committees<br />

Waterpo<strong>in</strong>t mapp<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Water resource management<br />

Water Sector Development Programme<br />

Water <strong>and</strong> Sanitation Programme<br />

Zanzibar Strategy for Growth <strong>and</strong> Reduction of Poverty<br />

© UNICEF/Giacomo Pirozzi<br />

xix

© UNICEF/Julie Pudlowski<br />

Ma<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong><br />

20

Overview<br />

<strong>Children</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Women</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> 2010 argues that <strong>in</strong>vest<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> children <strong>and</strong> their mothers is<br />

the s<strong>in</strong>gle most important <strong>in</strong>vestment for <strong>Tanzania</strong>’s development. Given that children under<br />

18 years of age constitute 51% of the population, it will be their creativity <strong>and</strong> productivity that<br />

will determ<strong>in</strong>e if the goals of Vision 2025 are realised. Invest<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> their well-be<strong>in</strong>g now is the<br />

soundest <strong>in</strong>vestment <strong>Tanzania</strong> can make to secure economic, social <strong>and</strong> political stability <strong>and</strong><br />

prosperity.<br />

The report provides <strong>in</strong>-depth analysis of the situation of children <strong>and</strong> women <strong>in</strong> six areas: health;<br />

nutrition; water, sanitation <strong>and</strong> hygiene; education; HIV <strong>and</strong> AIDS; <strong>and</strong> child protection. It seeks<br />

to provide guidance on what needs to happen to provide an enabl<strong>in</strong>g environment <strong>in</strong> which<br />

children can thrive <strong>and</strong> their potential can be catalyzed for their own benefit <strong>and</strong> for <strong>Tanzania</strong><br />

as a whole. It aims to drive evidenced-based advocacy <strong>and</strong> positive change for children <strong>and</strong><br />

women <strong>in</strong> the country, <strong>and</strong> to serve as a reference tool for Government <strong>and</strong> non-state actors<br />

work<strong>in</strong>g towards development outcomes.<br />

<strong>Children</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Women</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> 2010 comes at a critical juncture. Its production has co<strong>in</strong>cided<br />

with a number of important developments, such as the:<br />

© UNICEF/Julie Pudlowski<br />

• Enactment of the Law of the Child Act by the <strong>Tanzania</strong>n Parliament <strong>in</strong> November 2009<br />

• Launch of the National Roadmap Strategic Plan to Accelerate Reduction of Maternal,<br />

Newborn <strong>and</strong> Child Deaths <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> 2008-2015 (better known as the “One Plan”) by<br />

President Kikwete <strong>in</strong> 2009<br />

• Draft<strong>in</strong>g of sector <strong>and</strong> sub-sector policies that to date have represented major gaps <strong>in</strong> child<br />

well-be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the:<br />

º Integrated Early Childhood Development Policy<br />

º National Food <strong>and</strong> Nutrition Policy<br />

º National Sanitation <strong>and</strong> Hygiene Policy<br />

• Launch of Ajenda ya Watoto (The <strong>Children</strong>’s Agenda) <strong>in</strong> June 2010 by the M<strong>in</strong>ister for<br />

Community Development, Gender <strong>and</strong> <strong>Children</strong>.<br />

With<strong>in</strong> the broader national context, the analysis has been used to <strong>in</strong>form the design <strong>and</strong> is<br />

expected to serve as an important reference for guid<strong>in</strong>g the implementation of the second phase<br />

of the National Strategy for Growth <strong>and</strong> the Reduction of Poverty (2010-2015) (MKUKUTA II)<br />

so as to promote a strong focus on child outcomes <strong>and</strong> the development of a comprehensive<br />

social protection agenda <strong>in</strong> the country. The report highlights the significant achievements <strong>in</strong><br />

child well-be<strong>in</strong>g over the last decade, <strong>and</strong> how one can learn from <strong>and</strong> build upon these ga<strong>in</strong>s<br />

to fully realise the rights of all <strong>Tanzania</strong>n children.<br />

1

<strong>Children</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Women</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong><br />

Fast facts on <strong>Tanzania</strong>n children <strong>and</strong> women<br />

Demographics<br />

22.2 million <strong>Children</strong> under 18 years<br />

8.1 million <strong>Children</strong> under five years<br />

8 million <strong>Children</strong> liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> poverty<br />

1.8 million Babies born every year<br />

Maternal <strong>and</strong> child survival<br />

5.7 Total Fertility Rate - rural women on average have 6.5 children;<br />

urban women 3.6 children<br />

1 <strong>in</strong> 4 Girls aged 15-19 years who have already begun childbear<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Nearly universal (97%) Pregnant women who attended at least one antenatal care visit<br />

Over half (54%) Babies born without skilled attendants<br />

25 Deaths every day of women dur<strong>in</strong>g pregnancy or childbirth<br />

Over 400<br />

Deaths every day of children under five years<br />

135 Deaths every day of babies less than one month<br />

Nutrition<br />

Over 2.5 million Number of children who are chronically malnourished<br />

1 <strong>in</strong> 7 (14%) Babies aged 4-5 months who are exclusively breastfed<br />

Education<br />

Nearly universal (96%) Net enrolment rate <strong>in</strong> primary school<br />

Two-thirds<br />

<strong>Children</strong> who complete primary school (St<strong>and</strong>ard VII)<br />

1:54 Pupil-teacher ratio <strong>in</strong> primary school<br />

9 <strong>in</strong> 10 <strong>Children</strong> <strong>in</strong> rural areas not enrolled <strong>in</strong> secondary school<br />

8,000 Girls who drop out of school every year due to pregnancy<br />

Water, sanitation <strong>and</strong> hygiene<br />

4 <strong>in</strong> 5 Schools without function<strong>in</strong>g h<strong>and</strong>-wash<strong>in</strong>g facilities<br />

3 <strong>in</strong> 5 Schools without an on-site water supply<br />

9 <strong>in</strong> 10 <strong>Children</strong> <strong>and</strong> caregivers who do not wash their h<strong>and</strong>s with soap<br />

after us<strong>in</strong>g the latr<strong>in</strong>e or clean<strong>in</strong>g a baby or before prepar<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong><br />

eat<strong>in</strong>g food<br />

HIV <strong>and</strong> AIDS<br />

Less than half<br />

One-third<br />

Child protection<br />

<strong>Women</strong> who know HIV transmission to babies can be prevented<br />

Infants born to HIV-positive mothers who received prophylaxis<br />

More than 9 <strong>in</strong> 10 <strong>Children</strong> under five years who do not have a birth certificate<br />

18 <strong>in</strong> 100 <strong>Children</strong> under 18 years who have lost one or both parents<br />

1 <strong>in</strong> 5 <strong>Children</strong> engaged <strong>in</strong> child labour (rural 25%; urban 8%)<br />

2

Overview<br />

The Law of the Child Act 2009<br />

The draft<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>Children</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Women</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> 2010 co<strong>in</strong>cided with the passage of the l<strong>and</strong>mark<br />

Law of the Child Act through the Bunge on 6 November 2009, the first unified piece of national<br />

legislation aimed at comprehensively protect<strong>in</strong>g the rights of children <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>. The law effectively<br />

domesticates the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child (CRC) <strong>and</strong> addresses fundamental<br />

issues related to children’s rights <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g non-discrim<strong>in</strong>ation, the right to a name <strong>and</strong><br />

nationality, the rights <strong>and</strong> duties of parents, the right to op<strong>in</strong>ion, <strong>and</strong> a framework of protection<br />

for children at greatest risk due to loss of parents, ab<strong>and</strong>onment, abuse or other causes.<br />

Like all groundbreak<strong>in</strong>g rights legislation, the new law has shortcom<strong>in</strong>gs reflect<strong>in</strong>g adherence to<br />

long-held socio-cultural norms. For example, the Act does not address discrim<strong>in</strong>ation regard<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the legal age of marriage, which rema<strong>in</strong>s at 15 years for girls <strong>and</strong> 18 years for boys. Underscor<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the need for further legislative action, the <strong>Tanzania</strong> Demographic <strong>and</strong> Health Survey 2004/5<br />

estimated that 25% of girls between 15 <strong>and</strong> 19 years of age were <strong>in</strong> child marriages, <strong>and</strong> 52% of<br />

women had commenced childbear<strong>in</strong>g by the age of 19. Maternal health research unequivocally<br />

demonstrates that adolescent girls face a significantly higher risk of death from pregnancy <strong>and</strong><br />

delivery related complications. The proportion of girls who become pregnant while attend<strong>in</strong>g<br />

school has been grow<strong>in</strong>g steadily. By 2007, around 8000 girls (about half from primary schools<br />

<strong>and</strong> half from secondary schools) became pregnant. In accordance with guidel<strong>in</strong>es <strong>in</strong> force at the<br />

time, all of these students were expelled, <strong>and</strong> for most it marked the end of their education.<br />

Corporal punishment also rema<strong>in</strong>s legal despite strong evidence that children who are beaten at<br />

home or school can suffer devastat<strong>in</strong>g physical <strong>and</strong> psychological damage that affects their sense of<br />

self-respect <strong>and</strong> self-worth. Engender<strong>in</strong>g fear <strong>and</strong> anger <strong>and</strong> underm<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g a child’s ability to learn,<br />

corporal punishment often leads to children runn<strong>in</strong>g away from their homes <strong>and</strong> dropp<strong>in</strong>g out of school.<br />

<strong>Children</strong>’s experience of violence can have profound impact on their adult lives. Victims of abuse all too<br />

frequently become abusers themselves or end up <strong>in</strong> abusive relationships. There is grow<strong>in</strong>g awareness<br />

of the long-last<strong>in</strong>g detriment of domestic <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutionalised violence <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g national advocacy<br />

to br<strong>in</strong>g about change.<br />

Child <strong>and</strong> maternal survival: Success <strong>and</strong> stagnation<br />

Over the last decade, <strong>Tanzania</strong> has made remarkable progress <strong>in</strong> reduc<strong>in</strong>g under-five mortality.<br />

S<strong>in</strong>ce 1999, the under-five mortality rate has decl<strong>in</strong>ed by almost 40%, a decrease equivalent to<br />

sav<strong>in</strong>g the lives of nearly 100,000 <strong>Tanzania</strong>n children every year. These ga<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong> child survival have<br />

largely been achieved through <strong>in</strong>vestment <strong>in</strong> effective, mostly low cost <strong>in</strong>terventions, <strong>in</strong> particular,<br />

<strong>in</strong>creased use of <strong>in</strong>secticide-treated mosquito nets, improved treatment of malaria, immunisation<br />

(which has reduced deaths from measles), <strong>and</strong> exp<strong>and</strong>ed coverage of Vitam<strong>in</strong> A supplementation<br />

(which boosts children’s immune systems).<br />

Despite this progress, around 155,000 children under-five years are dy<strong>in</strong>g annually, the vast<br />

majority from readily preventable causes. Malnutrition, malaria <strong>and</strong> diarrhoea (largely caused by<br />

dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g unsafe water <strong>and</strong> poor sanitation <strong>and</strong> hygiene) are the biggest killers. Nearly 50,000 of<br />

these deaths are of children less than one month old; of which three-quarters survive for less than<br />

a week. Newborn deaths are <strong>in</strong>extricably l<strong>in</strong>ked to the health of the mother dur<strong>in</strong>g pregnancy <strong>and</strong><br />

to the adequacy of obstetric care at delivery; most can be averted if coverage of basic maternal<br />

<strong>and</strong> neonatal <strong>in</strong>terventions is exp<strong>and</strong>ed.<br />

Yet over the last 15 years, maternal health has stagnated. The TDHS 2004/5 estimated <strong>Tanzania</strong>’s<br />

maternal mortality rate at 578 deaths per 100,000 live births, one of the highest <strong>in</strong> the world. The<br />

proportion of women giv<strong>in</strong>g birth at health facilities is still less than 50%. When an emergency arises,<br />

even if a woman reaches a facility <strong>in</strong> time, the widespread lack of skilled birth attendants <strong>and</strong> essential<br />

obstetric equipment <strong>and</strong> supplies, means that a safe delivery is far from guaranteed. As a result, a<br />

woman dies <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> every hour due to complications dur<strong>in</strong>g pregnancy or childbirth.<br />

3

<strong>Children</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Women</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong><br />

This tragedy of so many women <strong>and</strong> babies dy<strong>in</strong>g dur<strong>in</strong>g delivery or shortly after birth cannot<br />

be prolonged. The full implementation of the “One Plan” is urgently required to establish the<br />

foundation of maternal <strong>and</strong> child health <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>, <strong>and</strong> meet MDG 4 for under-five mortality<br />

<strong>and</strong> MDG5 for maternal mortality.<br />

National champions are needed for mothers <strong>and</strong> their children so that this long overdue <strong>in</strong>vestment<br />

becomes a reality. The benefits <strong>in</strong> terms of reduced maternal <strong>and</strong> child mortality <strong>and</strong> morbidity, longterm<br />

reductions <strong>in</strong> healthcare costs, <strong>and</strong> ga<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong> productivity will be noth<strong>in</strong>g short of formidable.<br />

The rationale for “One Plan” is that children require a cont<strong>in</strong>uum of care <strong>and</strong> programmes not<br />

only with<strong>in</strong> the health sector but also across sectoral boundaries. <strong>Children</strong> have needs for survival,<br />

development <strong>and</strong> protection that are <strong>in</strong>ter-related <strong>and</strong> re<strong>in</strong>force one another. But the current<br />

sectoral focus of targets <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>vestments <strong>in</strong> children – for example, health addresses the ‘child as<br />

patient’, education addresses the ‘child as student’ <strong>and</strong> so on – tends to compartmentalise children’s<br />

needs <strong>and</strong> to divide up the child <strong>in</strong>to artificial pieces. As a consequence significant gaps <strong>in</strong> outcomes<br />

persist or open up <strong>in</strong> the way duty-bearers respond to the needs of <strong>Tanzania</strong>n children.<br />

M<strong>in</strong>isterial divisions, which are then replicated at local service delivery level, must be bridged so<br />

that children do not fall through those gaps. Coord<strong>in</strong>ated programmes that are designed for the<br />

whole child are required, so that they may respond to children’s evolv<strong>in</strong>g developmental needs<br />

throughout their life course from conception through adolescence.<br />

Nutrition <strong>and</strong> hygiene: Critical but overlooked<br />

Unlike child survival, very little progress has been made <strong>in</strong> reduc<strong>in</strong>g chronic malnutrition. About<br />

four out of ten children <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> are stunted, deny<strong>in</strong>g these children the opportunity to develop<br />

to their full mental <strong>and</strong> physical potential. The most harm occurs dur<strong>in</strong>g pregnancy <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> the first<br />

two years of a child’s life. Malnutrition is also l<strong>in</strong>ked to one-third of all under-five deaths, mak<strong>in</strong>g<br />

it the s<strong>in</strong>gle largest cause of under-five deaths <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>. Yet, simple, cost-effective, affordable<br />

<strong>in</strong>terventions are available that can have last<strong>in</strong>g impact on a child’s prospect.<br />

Exclusive breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>itiated with<strong>in</strong> one hour of birth <strong>and</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g for six months is the most<br />

effective life-sav<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>tervention. In addition, to breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g – which optimally should cont<strong>in</strong>ue<br />

until two years of age – young children from six months of age need to be fed frequently <strong>and</strong> given a<br />

variety of foods to prevent malnutrition. To facilitate change <strong>in</strong> feed<strong>in</strong>g practices, women <strong>and</strong> their<br />

families must be rout<strong>in</strong>ely counselled <strong>and</strong> supported dur<strong>in</strong>g antenatal <strong>and</strong> postnatal care on the<br />

importance of breastfeed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> safe wean<strong>in</strong>g. The TDHS 2004/5 found that only 13.5% of <strong>in</strong>fants<br />

aged 4-5 months were still exclusively breastfed.<br />

Food fortification is another proven, low cost, effective way to reduce malnutrition. Most countries<br />

address micronutrient deficiencies by fortify<strong>in</strong>g common foods such as salt with iod<strong>in</strong>e, oils with<br />

vitam<strong>in</strong> A, <strong>and</strong> flour with iron. Every shill<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>vested <strong>in</strong> food fortification will yield an eight-fold return.<br />

Food fortification could reduce anaemia <strong>in</strong> children <strong>and</strong> women by 20% to 30%, reduce key birth<br />

defects by 30%, <strong>and</strong> vitam<strong>in</strong> A deficiency by 30%.<br />

So too, h<strong>and</strong>-wash<strong>in</strong>g at critical times – after us<strong>in</strong>g a toilet, before prepar<strong>in</strong>g meals, before eat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

or feed<strong>in</strong>g a child, <strong>and</strong> after attend<strong>in</strong>g a child who has defecated – is a simple, cost-effective way of<br />

sav<strong>in</strong>g children’s lives. Research <strong>in</strong>dicates that it can reduce the risk of diarrhoeal disease – a major<br />

killer of children under-five – by up to 47%. The <strong>in</strong>tegration of basic hygiene education <strong>in</strong>to maternal<br />

health services <strong>and</strong> the curriculum <strong>in</strong> schools are needed to facilitate behavioural change.<br />

Improvements <strong>in</strong> basic nutrition <strong>and</strong> hygiene will have immediate <strong>and</strong> long-last<strong>in</strong>g benefits for children<br />

<strong>and</strong> the economy. Well-nourished, healthy children learn better, <strong>and</strong>, with fewer children succumb<strong>in</strong>g<br />

to illness <strong>and</strong> recover<strong>in</strong>g faster when they do, a significant burden is lifted from the health system.<br />

4

Overview<br />

Water <strong>and</strong> sanitation: A new momentum?<br />

Clean <strong>and</strong> safe water, adequate sanitation facilities <strong>and</strong> safe hygiene practices <strong>in</strong> households,<br />

schools <strong>and</strong> health facilities are fundamental to women’s <strong>and</strong> children’s health. Diarrhoea <strong>and</strong> acute<br />

respiratory <strong>in</strong>fections – which cause 40% of under-five deaths worldwide – are closely l<strong>in</strong>ked to<br />

poor water quality, sanitation <strong>and</strong> hygiene. In addition, one-quarter of neonatal deaths are due to<br />

<strong>in</strong>fection <strong>and</strong> diarrhoea, <strong>and</strong> sepsis is a lead<strong>in</strong>g cause of maternal mortality, all of which are affected<br />

by use of unclean water <strong>and</strong> poor hygiene at delivery <strong>and</strong> postpartum.<br />

Improvements <strong>in</strong> water supply <strong>and</strong> sanitation will br<strong>in</strong>g enormous benefits to the lives of <strong>Tanzania</strong>n<br />

women <strong>and</strong> children. The burden of collect<strong>in</strong>g water is largely borne by women <strong>and</strong> children,<br />

especially girls. And the lack of clean, private latr<strong>in</strong>es <strong>in</strong> schools is a common reason for girls not<br />

to attend school or drop out altogether. Simple access to decent toilets can avert the tragic loss of<br />

education <strong>and</strong> future livelihoods for adolescent girls. Indeed, global analysis has estimated that there<br />

is an astonish<strong>in</strong>g return on <strong>in</strong>vestment <strong>in</strong> water <strong>and</strong> sanitation: for every $1 spent on water supply <strong>and</strong><br />

sanitation, a benefit of $11.5 will accrue <strong>in</strong> terms of time <strong>and</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ancial sav<strong>in</strong>gs – <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g more time<br />

at work, reduced medical costs, less school absence <strong>and</strong> decreased costs for hospital services.<br />

Yet data for both urban <strong>and</strong> rural water supply <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong> show a decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> household access s<strong>in</strong>ce<br />

2000. Analysis of the Household Budget Survey reveals that poorer households pay three times<br />

more for water as a proportion of their <strong>in</strong>come. In addition, three out of five schools <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong><br />

have no on-site water supply, <strong>and</strong> four out five schools have no function<strong>in</strong>g h<strong>and</strong>-wash<strong>in</strong>g facilities.<br />

On average, the school sanitation ratio is 61 students per latr<strong>in</strong>e, compared with the target of<br />

one toilet for every 20 girls <strong>and</strong> one for every 25 boys. Almost two-thirds of health facilities lack a<br />

regular water supply <strong>and</strong> one-third have no toilets for clients.<br />

It was hoped that the Water Sector Development Programme (WSDP) launched <strong>in</strong> 2007 will turn<br />

this deteriorat<strong>in</strong>g status around. Resources for Investment <strong>in</strong> water supply have almost doubled <strong>in</strong><br />

the last few years, <strong>and</strong> funds are now allocated to all districts to improve rural water supply rather<br />

than targeted to a few major projects. For the sake of susta<strong>in</strong>ability, it is very positive that the<br />

Government of <strong>Tanzania</strong> is the largest s<strong>in</strong>gle contributor to the WSDP. But even with the <strong>in</strong>creased<br />

level of fund<strong>in</strong>g, the resources for the sector are not able to keep up with population growth.<br />

Despite their proven low-cost effectiveness, f<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g for sanitation <strong>and</strong> hygiene promotion has not yet<br />

received the attention of policy makers, donors <strong>and</strong> the public. The sub-sector receives barely 1% of<br />

the total water <strong>and</strong> sanitation budget <strong>and</strong> funds are largely spent on costly sewerage systems <strong>in</strong> a few<br />

towns <strong>and</strong> cities. Responsibility for this critical sub-sector is fragmented across the health, water <strong>and</strong><br />

education m<strong>in</strong>istries <strong>and</strong> the correspond<strong>in</strong>g structures at the local government level.<br />

Fortunately, there recently has emerged a heightened awareness of the critical importance of<br />

sanitation <strong>and</strong> hygiene for overall health <strong>and</strong> well-be<strong>in</strong>g. Four m<strong>in</strong>istries, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the one responsible<br />

for the policy of decentralis<strong>in</strong>g service provision – Health <strong>and</strong> Social Welfare, Education <strong>and</strong><br />

Vocational Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, Water <strong>and</strong> Infrastructure, <strong>and</strong> the Prime M<strong>in</strong>ister’s Office (PMO-RALG) –<br />

have established a coord<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g mechanism <strong>and</strong> have signed a Memor<strong>and</strong>um of Underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g that<br />

could br<strong>in</strong>g new momentum to this neglected sub-sector. There is also a National Sanitation <strong>and</strong><br />

Hygiene Policy that is be<strong>in</strong>g drafted <strong>and</strong> grow<strong>in</strong>g recognition of the need to step up <strong>in</strong>vestments <strong>in</strong><br />

safe water, better hygiene <strong>and</strong> sanitation <strong>in</strong> schools <strong>and</strong> health facilities.<br />

Improv<strong>in</strong>g outcomes for women <strong>and</strong> children will depend on the efficient <strong>in</strong>tegration of <strong>in</strong>terventions to<br />

achieve broad-based coverage; water, sanitation <strong>and</strong> hygiene are three parts of the same solution.<br />

© UNICEF/Julie Pudlowski<br />

Early childhood development: A new frontier<br />

Along with the ‘One Plan’, <strong>in</strong>tegrated early childhood development (IECD) has the potential to<br />

be the vanguard <strong>in</strong> the fight aga<strong>in</strong>st child poverty <strong>and</strong> deprivation <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong>. An IECD Policy<br />

has been drafted collaboratively between three m<strong>in</strong>istries –Community Development, Gender<br />

5

<strong>Children</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Women</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Tanzania</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>Children</strong>, Education <strong>and</strong> Vocational Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> Health <strong>and</strong> Social Welfare. The rationale<br />

for ECD is that gaps <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual ability widen significantly <strong>in</strong> the early years between advantaged<br />

<strong>and</strong> disadvantaged children. With a focus upon children <strong>in</strong> vulnerable households who are at the<br />

greater risk of disease <strong>and</strong> malnutrition <strong>and</strong> often have poorer educational outcomes, ECD can<br />

close these gaps.<br />

Support for community-based parent<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> ECD <strong>in</strong>terventions will help ensure children grow up<br />

healthy, well nourished <strong>and</strong> well-prepared for school. Investments <strong>in</strong> early childhood have been<br />

shown to give a seven-fold return <strong>and</strong> are much more cost-efficient than remedial programmes<br />

later <strong>in</strong> a child’s life.<br />

Recognis<strong>in</strong>g the importance of ECD, the second phase of the Primary Education Development<br />

Programme 2007-2011 (PEDP II) urged the establishment of pre-primary education for 5-6 year<br />

olds <strong>in</strong> every primary school us<strong>in</strong>g exist<strong>in</strong>g school facilities, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g pre-primary children <strong>in</strong><br />

the $10 capitation grant. Little data on pre-schools is available, but the NER for 5-6 year olds rose<br />

from 24.6% <strong>in</strong> 2004 to 36.2% <strong>in</strong> 2008. However, the majority of the pre-primary schools attached<br />

to primary schools are still poorly funded <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>adequately staffed, <strong>and</strong> over 80% of ECD centres<br />

that are not attached to primary schools are unregistered. Services <strong>in</strong> rural areas <strong>and</strong> poor urban<br />

areas are particularly limited.<br />

Education: The challenge of quality <strong>and</strong> equity<br />

<strong>Children</strong>’s needs change throughout their life course, so that different <strong>in</strong>terventions are required<br />

at different po<strong>in</strong>ts <strong>in</strong> time. As children age they are naturally predisposed towards <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g self<br />

actualisation <strong>and</strong> the rights that become more significant to them are those around education,<br />

participation <strong>and</strong> protection.<br />

<strong>Tanzania</strong> has made significant progress <strong>in</strong> the education sector <strong>in</strong> the last ten years. Follow<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

abolition of school fees <strong>in</strong> 2001 <strong>and</strong> massive <strong>in</strong>vestments <strong>in</strong> the construction of new classrooms,<br />

enrolment <strong>in</strong> primary schools skyrocketed to reach near universal coverage, with parity between<br />

girls <strong>and</strong> boys. Secondary education has also exp<strong>and</strong>ed at unprecedented rates, though coverage<br />

rema<strong>in</strong>s limited to better-off households <strong>and</strong> historically advantaged parts of the country. Less<br />

than one <strong>in</strong> ten children from rural area is enrolled. Beyond primary school, completion rates for<br />

girls dim<strong>in</strong>ish the higher the grade. Hard-to-reach <strong>and</strong> disabled children cont<strong>in</strong>ue to be excluded<br />

from formal education.<br />

But the very success <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g access so rapidly may have come at the expense of learn<strong>in</strong>g<br />

outcomes. Less than 70% of students actually complete all primary grades <strong>and</strong> only about 52%<br />

pass the Primary School Leav<strong>in</strong>g Exam<strong>in</strong>ation. The number of primary school teachers has<br />

not kept pace with the <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> student numbers lead<strong>in</strong>g to overcrowded classrooms. On<br />

average, there are 54 students per teacher, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> rural areas more than 12 children share a<br />

s<strong>in</strong>gle maths textbook.<br />

The Government recognises that a well-educated citizenry is the lynchp<strong>in</strong> of poverty reduction<br />

<strong>and</strong> the future economic prosperity of the nation. A grow<strong>in</strong>g share of GDP is used to f<strong>in</strong>ance the<br />

sector, though the percentage is still below the recommended m<strong>in</strong>imum of 20% of government<br />

spend<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> there is a worry<strong>in</strong>g lack of transparency around education budgets <strong>and</strong> expenditure.<br />

Infrastructure dem<strong>and</strong>s will cont<strong>in</strong>ue to exp<strong>and</strong> with population growth, but dedicated <strong>and</strong> skilled<br />

teachers are needed most of all. A national <strong>in</strong>-service teacher tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g programme together with<br />

salaries <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>centives to attract talented young <strong>Tanzania</strong>ns to the profession will be two key<br />

components <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g the quality of education <strong>and</strong> conv<strong>in</strong>c<strong>in</strong>g parents <strong>and</strong> pupils of the value<br />

of stay<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> school.<br />

6

Overview<br />

HIV <strong>and</strong> AIDS: Address<strong>in</strong>g the drivers of the disease<br />

The <strong>in</strong>cidence of HIV <strong>and</strong> AIDS will not be significantly reduced unless the <strong>in</strong>fluence of gender norms<br />

on the risk of transmission is fully recognised. <strong>Women</strong> now account for 60% of new <strong>in</strong>fections.<br />

Data from the <strong>Tanzania</strong>n HIV/AIDS <strong>and</strong> Malaria Indicator Survey 2007/8 show that prevalence<br />

among young women <strong>in</strong>creases sharply from 1.3% <strong>in</strong> adolescent females aged 15-19 years to 6.3%<br />

among women aged 20-24 years. This highlights the need for early prevention <strong>in</strong>terventions. HIV<br />

prevalence among adolescent girls is almost twice that of boys. Lack of access to <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

<strong>in</strong>creases the risk of HIV transmission. Less than 40% of girls aged 15-19 years have comprehensive<br />