Download - Delhi Heritage City

Download - Delhi Heritage City

Download - Delhi Heritage City

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Nomination to UNESCO’s List of<br />

World <strong>Heritage</strong> Cities<br />

DELHI: A <strong>Heritage</strong> <strong>City</strong><br />

Submission for Tentative Listing<br />

January 2012<br />

Logo created from IGNCA and INTACH, <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter for the exhibition, “<strong>Delhi</strong>: A Living <strong>Heritage</strong>.”

Contents<br />

Tentative List Submission<br />

Name of the Property 5<br />

Description of the Nominated Area<br />

- Mehrauli 12<br />

- Nizamuddin 18<br />

- Shahjahanabad 26<br />

- New <strong>Delhi</strong> 32<br />

Justification of Outstanding Universal Value<br />

Criteria met<br />

- (ii) 38<br />

- (v) 39<br />

- (vi) 40<br />

Statements of authenticity and integrity 42<br />

Comparison with other similar properties 45<br />

- Historic Centre of Rome, the Properties<br />

of the Holy See in that <strong>City</strong> Enjoying<br />

Extraterritorial Rights and San Paolo Fuori<br />

le Mura<br />

- Historic Cairo<br />

- Samarkand: Crossroads of Cultures<br />

- Lahore<br />

- Agra<br />

- Lucknow<br />

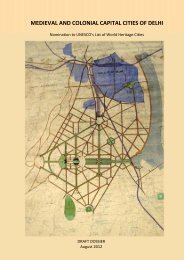

Map of Nominated Area<br />

<strong>Delhi</strong>’s historic eight capital cities<br />

INTACH- <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 3

Name of the<br />

Property<br />

<strong>Delhi</strong>: A <strong>Heritage</strong> <strong>City</strong><br />

State, Province or Region:<br />

Latitude and Longitude:<br />

New <strong>Delhi</strong><br />

Latitude:28°40’ N, Longitude:77°12’E<br />

State Party<br />

INDIA<br />

Nomination<br />

Submitted by<br />

<strong>Delhi</strong> Tourism and Transportation Development Corporation<br />

Government of the National Capital Territory of <strong>Delhi</strong><br />

Submission<br />

prepared by<br />

Name:<br />

E-mail:<br />

INTACH, <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter<br />

delhiheritagecity@gmail.com<br />

Address: 71, Lodhi Estate, New <strong>Delhi</strong>, 110003<br />

Institution:<br />

Indian National Trust for Art and<br />

Cultural <strong>Heritage</strong><br />

Fax: + 91 11 2461 1290<br />

Telephone: + 91 11 2469 2774<br />

Date of Submission: January, 2012<br />

Authorised Signatory<br />

MD, DTTDC<br />

INTACH- <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 5

DELHI: A HERITAGE CITY Nomination to UNESCO’s List of World <strong>Heritage</strong> Cities Description of the Nominated Area<br />

Description<br />

<strong>Delhi</strong> known as Kalkaji. Nearby is the<br />

Kalkaji temple, the site of a temple to<br />

the goddess Kalka Devi and probably<br />

even in Ashoka’s time a temple stood<br />

here.<br />

a<br />

‘<strong>Delhi</strong>’, being nominated for listing with<br />

UNESCO as a World <strong>Heritage</strong> <strong>City</strong> is<br />

best described as a living city, in which<br />

the historical past and contemporary<br />

life coexist harmoniously .<br />

EVOLUTION OF DELHI – A<br />

Historical Reference<br />

The historic settlement that we know<br />

today as <strong>Delhi</strong>, took shape in a roughly<br />

triangular patch of land. One side of<br />

the triangle is made up by the Yamuna<br />

river, and the other two consist of hilly<br />

spurs at the northern extreme of the<br />

Aravalli range of mountains. At a local<br />

level these two natural features have<br />

provided a varied landscape – hills<br />

well covered with vegetation, as well<br />

as a fertile alluvial plain. The wider<br />

regional importance of <strong>Delhi</strong> has<br />

historically stemmed from its crucial<br />

geographical location within the<br />

Indian subcontinent. It is located at<br />

the northern end of the Gangetic plain;<br />

at a point where the plain narrows<br />

to a neck of land between the great<br />

rivers and Himalayas to the north,<br />

and the Aravallis and the Thar Desert<br />

to the south. It is therefore a gateway<br />

to the fertile Gangetic plain, which<br />

empire-builders from early times have<br />

sought to control, and to the Southern<br />

peninsula beyond.<br />

The <strong>Delhi</strong> region was inhabited by tool<br />

making hominids, followed by human<br />

beings, probably as far back as 100,000<br />

years ago. In this pre-historic period<br />

it was mainly the hilly regions to the<br />

south of <strong>Delhi</strong> that were occupied.<br />

The area was almost certainly covered<br />

with rich vegetation and ample wildlife<br />

– ideal for the hunting-gathering<br />

lifestyle of the Stone Age people. It<br />

is also clear that the River Yamuna at<br />

that time flowed through these hills.<br />

The river in fact has changed course<br />

several times and at least six old beds<br />

have been identified. Interestingly, the<br />

location of Stone Age sites and their<br />

sequence suggests that pre-historic<br />

people moved with the river.<br />

When agriculture became the primary<br />

source of food for ancient populations<br />

there was a shift in settlements –<br />

away from the ridge and towards the<br />

plains and more particularly along the<br />

Yamuna. There is evidence that <strong>Delhi</strong><br />

was settled during the Late Harappan<br />

period. This was a phase, sometime<br />

between 2000-1000 B.C., when<br />

the sophisticated urban Harappan<br />

civilization was past its heyday, and its<br />

cities had been replaced by scattered<br />

rural settlements.<br />

<strong>Delhi</strong>, as we know<br />

it today is an<br />

amalgamation of many<br />

cities, built at different<br />

times in its thousandyear<br />

history.<br />

a. The city of <strong>Delhi</strong> before the<br />

siege, from the Illustrated<br />

London News, Jan[1].16, 1858,<br />

British Library<br />

a<br />

b<br />

a. Archaeological findings at<br />

the Purana Qila site<br />

b. Ashokan Rock Edict<br />

c. Late Harappan Period<br />

Pottery<br />

c<br />

The Late Harappan phase was<br />

followed by the Vedic Age, when the<br />

ancient scriptures or the Vedas were<br />

first composed. In the early part of the<br />

first millennium B.C. certain events<br />

were taking place that are believed to<br />

have formed the basis of one of the<br />

great epics of India – the Mahabharata.<br />

This is the tale of a rivalry and great<br />

war between two sets of cousins –<br />

the Kauravas and the Pandavas. The<br />

capital city established by the latter,<br />

known as Indraprastha, has in the local<br />

tradition been identified with the site<br />

of the Purana Qila, beside the Yamuna<br />

in <strong>Delhi</strong>. Archaeological evidence from<br />

the site has been unable to point to<br />

anything definite.<br />

Around the 6th century B.C. an active<br />

phase of state formation began in<br />

North India, with the rise of several<br />

territorial states or Mahajanpadas.<br />

At this time <strong>Delhi</strong>, though not one of<br />

the major political centres, was an<br />

important point on the great north<br />

Indian trade route, known as the<br />

Uttarapatha. It was thus an ideal place<br />

for the emperor Ashoka, who ruled<br />

over the a large territory in the third<br />

century B.C., to put up an inscription<br />

containing what is known to us as his<br />

rock edict. The edict was inscribed<br />

on a large boulder on a hilly piece of<br />

ground, in an area in modern south<br />

In the subsequent centuries too, <strong>Delhi</strong><br />

probably formed a part of states<br />

which had their centres of power<br />

elsewhere, such as the Sungas, Shakas<br />

and Kushanas. During the Gupta<br />

period, sometime in the fourth century<br />

A.D. a remarkable commemorative<br />

pillar made out of a very high quality<br />

iron was set up, maybe somewhere<br />

in the neighbourhood of <strong>Delhi</strong>. The<br />

inscriptional evidence is not entirely<br />

clear but it is believed that this pillar<br />

was moved at least once during its<br />

history. Today it is located in the middle<br />

of the oldest mosque in the city, in the<br />

Qutb Minar complex.<br />

By the eight century <strong>Delhi</strong> had come<br />

under the sway of the Tomars, one of<br />

the several Rajput dynasties that had<br />

their origins in Rajasthan. The Tomars<br />

first established fortifications in the<br />

village of Anangpur, and around the<br />

large reservoir known as Surajkund,<br />

just south of <strong>Delhi</strong>. In the mid-eleventh<br />

century, Anangpal II of this dynasty<br />

built the fortified city of Lal Kot, located<br />

in present day Mehrauli.<br />

The Chauhans, headquartered in Ajmer,<br />

wrested control of <strong>Delhi</strong> from the<br />

Tomars in the twelfth century. Under<br />

Prithviraj Chauhan the fortifications<br />

of Lal Kot were extended to enclose a<br />

larger space, forming the fort known as<br />

Qila Rai Pithora. A rich material culture,<br />

including more than a score beautifully<br />

carved stone temples formed a part of<br />

this city. The temple pillars can still be<br />

seen on the site as they were re-used in<br />

the construction of the Quwwat ul Islam<br />

mosque – next to the Qutb Minar.<br />

6<br />

State Party - INDIA INTACH- <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 7

DELHI: A HERITAGE CITY Nomination to UNESCO’s List of World <strong>Heritage</strong> Cities Description of the Nominated Area<br />

a b c<br />

a<br />

b<br />

Then towards the end of the twelfth<br />

century, the Chauhans were overthrown<br />

by a new entrant on the scene. The<br />

forces of Mohammad Ghori, a Central<br />

Asian Turk with a base in Ghazni,<br />

defeated the armies of Prithviraj<br />

Chauhan at the battle of Tarain in 1192.<br />

In early 1193, his general Qutbuddin<br />

Aibak captured <strong>Delhi</strong> and established<br />

the capital of Ghori’s Indian territories<br />

in the fort of Qila Rai Pithora. The Turk<br />

conquest laid the groundwork for the<br />

establishment of the <strong>Delhi</strong> Sultanate,<br />

which was to last in some form or the<br />

other until the arrival of the Mughals in<br />

the sixteenth century. Under the Turks,<br />

from the early thirteenth century <strong>Delhi</strong><br />

acquired a new importance as the<br />

capital of a dynamic and expanding<br />

empire.<br />

The Turk conquerors were Muslims,<br />

and avowedly committed to the setting<br />

up of an Islamic state, with the name of<br />

the Caliph being included in the Friday<br />

sermon and on coinage. One of the<br />

early Sultans, Iltutmish (1211-36) even<br />

sought to give his position legitimacy in<br />

the eyes of the orthodox by obtaining<br />

a letter of investiture from the Caliph<br />

at Baghdad, confirming Iltutmish’s<br />

title as sultan of India. Simultaneously<br />

however great changes were occurring<br />

in the Islamic world. The Mongols<br />

under Chengiz Khan were wreaking<br />

havoc over Central and West Asia,<br />

and important centres of Islam like<br />

Bukhara and Baghdad were destroyed.<br />

Thus <strong>Delhi</strong> was looked upon as a last<br />

refuge for Islam in the East, and poets,<br />

scholars and men of letters fleeing<br />

the destruction of their homes found<br />

shelter in India, and particularly in<br />

<strong>Delhi</strong>.<br />

In its everyday practice however,<br />

the polity of the <strong>Delhi</strong> Sultanate was<br />

not based on orthodox Islam, which<br />

would have advocated a harsh line<br />

with non-believers. And here, the<br />

role and influence of the Sufis was<br />

probably a factor. The Sufi saints were<br />

among those who came to <strong>Delhi</strong> in<br />

the wake of the Turkish conquerors.<br />

Qutbuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki, the Chishti<br />

Sufi, was one of the several who made<br />

<strong>Delhi</strong> their base, and contributed to<br />

<strong>Delhi</strong>’s acquiring a leading position<br />

in the sacred geography of Islam in<br />

the Indian sub-continent. The city in<br />

fact came to be called Hazrat-e-Dehli,<br />

or ‘the venerable <strong>Delhi</strong>’. The saints,<br />

with their liberal religious practice<br />

attracted not only converts and<br />

devotees in large numbers, they also<br />

provided the political power with a<br />

model of governance that was based on<br />

a tolerance of non-Muslim populations.<br />

<strong>Delhi</strong>, even as it was the capital of an<br />

empire that purportedly derived its<br />

legitimacy from Islam, continued to<br />

have a large Hindu population.<br />

The saints’ hospices and shrines and<br />

their spheres of influence, were also the<br />

setting for a cultural interaction that<br />

In Alai Darwaza. the<br />

use of red sandstone<br />

and marble in<br />

combination, the<br />

hemispherical dome<br />

and its horseshoe<br />

arch mark a high<br />

point in Sultanate<br />

architecture.<br />

a. Surajkund: A reservoir in the<br />

village of Anangpur, south of<br />

<strong>Delhi</strong> © ASI.<br />

b. Built in the middle of the<br />

eleventh century by the Tomar<br />

ruler Anangpal II, the fort of Lal<br />

Kot (‘Red Fort’) © ASI.<br />

c. Sculptures in Mehrauli<br />

© ASI<br />

a. Fort Walls and bastion of<br />

Siri, the second city of <strong>Delhi</strong>.<br />

b.a. The massive bastions of<br />

Tughlaqabad tower over the<br />

rocky ground.<br />

was reflected in syncreticism outside<br />

the religious sphere. This included<br />

developments in architecture, music,<br />

literature and language, which brought<br />

together diverse traditions to create<br />

a composite style that soon gained<br />

influence in the entire sub-continent.<br />

In the first century of the <strong>Delhi</strong><br />

Sultanate, though the concentration<br />

of population continued to be highest<br />

in Mehrauli, in and around Qila Rai<br />

Pithora, some settlements were coming<br />

up closer to the river. One important<br />

reason for this was the need to provide<br />

access to a reliable source of water. In<br />

the mid-thirteenth century the Sufi<br />

saint Nizamuddin Auliya established<br />

his seat or khanqah at the suburb of<br />

Ghiaspur, today known as Nizamuddin.<br />

Around 1288 Sultan Kaiqubad built<br />

a walled palace at Kilokhari, about a<br />

kilometer from Ghiaspur. Kaiqubad’s<br />

successor Jalaluddin, who founded<br />

the Khilji Dynasty in 1290, was unsure<br />

of the loyalty of the people of the old<br />

city at Mehrauli, and therefore made<br />

Kilokhari his headquarters. Soon the<br />

wealthy and powerful nobles and<br />

merchants of <strong>Delhi</strong> built houses in<br />

Kilokhari, markets were established<br />

and it came to be known as the shahare-nau,<br />

or ‘new city’.<br />

The old town at Mehrauli continued<br />

to be important and was again the<br />

capital under Jalaluddin’s successor<br />

Alauddin. One factor that checked the<br />

move towards the river was strategic<br />

necessity, and the fortifications of<br />

Qila Rai Pithora on the ridge were<br />

important for defense, particularly<br />

when the Mongols threatened <strong>Delhi</strong> in<br />

the late thirteenth and early fourteenth<br />

centuries. The emperor Alauddin Khilji<br />

found himself repeatedly engaging<br />

them in battle on the plain of Siri,<br />

located north of Mehrauli. Alauddin<br />

decided to build a fortification, and this<br />

led to the founding of the new capital of<br />

Siri in the early fourteenth century.<br />

The founder of the Tughlaq dynasty,<br />

Ghiasuddin Tughlaq, was also very<br />

conscious of the threat of the Mongols.<br />

His fortified capital of Tughlaqabad<br />

was built around 1321-25, on the rocky<br />

scarps of the ridge in the south-eastern<br />

corner of the <strong>Delhi</strong> triangle. The rocks<br />

on the site provided ample building<br />

material, the heights reinforced the<br />

defenses of the fort, and the natural<br />

drainage line of the ridge could be<br />

dammed to provide a source of water.<br />

Ghiasuddin’s successor Mohammad<br />

Tughlaq moved back towards the old<br />

city at Mehrauli, but in the meantime<br />

the population of the city had been<br />

growing and spilling outside the walls.<br />

Conscious of the need for security,<br />

Mohammad Tughlaq decided to build a<br />

line of fortifications linking the forts of<br />

the Qila Rai Pithora and Siri. The space<br />

thus enclosed was named Jahanpanah,<br />

and Mohammad built an impressive<br />

8<br />

State Party - INDIA INTACH- <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 9

DELHI: A HERITAGE CITY Nomination to UNESCO’s List of World <strong>Heritage</strong> Cities Description of the Nominated Area<br />

a<br />

b<br />

c<br />

a<br />

b<br />

c<br />

palace complex (Bijai Mandal) and<br />

congregational mosque (Begampur<br />

Masjid) in it.<br />

By the mid-fourteenth century the<br />

Mongol threat had receded and from<br />

this point onwards there was a decided<br />

move closer to the river. Firoz Shah<br />

Tughlaq’s city of Firozabad, built in<br />

the 1350s, was towards the north,<br />

on the river. The end of the Tughlaq<br />

dynasty saw a sharp decline in the<br />

power and territories of the <strong>Delhi</strong><br />

Sultante, underlined by the invasion of<br />

the Timur (also known as Tamerlane)<br />

in 1398. The succeeding dynasties<br />

of the Syeds and the Lodis ruled over<br />

considerably shrunken territories and<br />

have not left behind any discernable<br />

cities. Mubarak Shah of the short-lived<br />

Syed dynasty is said to have established<br />

a city called Mubarakabad near the<br />

Yamuna, but no trace of it remains.<br />

The <strong>Delhi</strong> Sultanate came to an end<br />

in 1526, when Babur, a descendant of<br />

Timur, defeated the forces of the last<br />

Lodi Sultan, Ibrahim, and established<br />

the Mughal dynasty. His successor<br />

Humayun built the city of Dinpanah in<br />

the 1530s, just north of the shrine of<br />

Nizamuddin. Coincidentally the citadel<br />

was placed on the site of the village<br />

of Indarpat, popularly identified<br />

with the ancient city of Indraprastha.<br />

Humayun’s reign was interrupted<br />

by that of the Suri dynasty, and Sher<br />

Shah Suri made his own additions to<br />

Dinpanah, and established the city of<br />

Shergarh around it.<br />

Humayun’s successor Akbar moved the<br />

capital of the Mughal empire to Agra,<br />

but <strong>Delhi</strong> did not lose its importance<br />

as an important centre of trade and<br />

culture. In particular the Sufi shrines<br />

of the city gave it a premier position in<br />

the sacred geography of Islam in India.<br />

The choice of <strong>Delhi</strong> for the mausoleum<br />

of Humayun, located in the vicinity of<br />

Nizamuddin’s shrine, underlined this<br />

importance.<br />

In 1639, Akbar’s grandson Shahjahan<br />

decided to shift the capital out of Agra,<br />

and <strong>Delhi</strong> was chosen as the site for<br />

his grand imperial city. The new city,<br />

called Shahjahanabad, was by the<br />

river, north of all of <strong>Delhi</strong>’s previous<br />

cities. This continued to be the seat<br />

of the Mughal emperor even as the<br />

empire declined in the eighteenth<br />

century, and the British East India<br />

Company came to control most of its<br />

erstwhile territories. Shahjahanabad,<br />

as the seat of the Mughal court saw a<br />

flowering of architecture, crafts, visual<br />

and performing arts, language and<br />

literature, that persisted well beyond<br />

the heyday of the Mughal empire.<br />

Through the nineteenth century the<br />

British ruled their Indian territories<br />

from their capital at Calcutta. <strong>Delhi</strong><br />

saw the upheaval of the Revolt of 1857<br />

and was for a while relegated to an<br />

administrative backwater. But the aura<br />

a. Pyramid of cells with the<br />

Ashokan pillar, Firoz Shah Kotla.<br />

© British Library<br />

b. Dinpanah, the city built by<br />

Humanyun in 1530’s<br />

c. In building architecture,<br />

new plans and shapes became<br />

popular. Monumental structures<br />

were built like the octagonal<br />

tomb of Muhammad Shah<br />

Sayyid and the Bada Gumbad.<br />

© ASI<br />

a. Shahjahanabad, The walled<br />

city of the Mughals<br />

b. The Coronation Darbar<br />

of 1911, where <strong>Delhi</strong> was<br />

proposed as the new capital<br />

city.<br />

c. Rashtrapati Bhawan,<br />

designed as Viceroy House for<br />

the British Imperial capital<br />

city.<br />

of the city survived. Its long history as<br />

the capital of powerful kingdoms and<br />

empires had invested it with a mystique<br />

and prestige that not even the British<br />

could ignore. <strong>Delhi</strong> had long been<br />

associated with sovereignty over India,<br />

and the British government tapped<br />

into this legacy by holding imperial<br />

Durbars assemblages in <strong>Delhi</strong> - in 1877<br />

to proclaim Victoria Empress of India,<br />

in 1903 to celebrate the coronation<br />

of Edward VII as Emperor of India,<br />

and in 1911 to similarly proclaim the<br />

coronation of George V.<br />

It was during the last Durbar of<br />

1911 that the decision to shift the<br />

British Indian capital to <strong>Delhi</strong> was<br />

announced, and a year later <strong>Delhi</strong><br />

became the capital. Simultaneously<br />

work began on the construction of a<br />

new imperial capital city, which was<br />

finally inaugurated in 1931 as New<br />

<strong>Delhi</strong>. New <strong>Delhi</strong> was planned and<br />

built as a garden city laid out around a<br />

grand ceremonial vista. While it owed<br />

inspiration to Baron Haussmann’s<br />

Paris and L’Enfant’s Washington D.C., it<br />

drew on Indian traditions with respect<br />

to design elements, decorative details,<br />

materials, and colonial forms such<br />

as the bungalow. Above all it carried<br />

forward the aura of <strong>Delhi</strong> and the city’s<br />

tradition of learning from and adopting<br />

a wide range of cultural influences.<br />

AREA PROPOSED FOR<br />

NOMINATION<br />

<strong>Delhi</strong> has accommodated the various<br />

cities built at different times in its long<br />

history. The physical limits of present<br />

day <strong>Delhi</strong> have expanded to engulf all<br />

these historic areas and the legacy of<br />

many dynasties that ruled over <strong>Delhi</strong>,<br />

lives on in these historic precincts.<br />

Of the eight historic ‘capital cities’,<br />

some like Ferozabad and Dinpanah<br />

have disappeared completely<br />

leaving just a few monumental<br />

structures but no trace of either the<br />

urban morphology or character of<br />

the city; others like Tughlaqabad<br />

have been encroached upon but<br />

their urban characteristics are still<br />

identifiable; while the later cities like<br />

Shahjahanabad, have their urban form<br />

and streetscape almost intact with only<br />

the buildings having been replaced<br />

with newer constructions over the<br />

last few decades. And there are some<br />

precincts that are an intricate tapestry,<br />

with over a thousand years of culture<br />

woven into the living traditional<br />

settlements.<br />

It is <strong>Delhi</strong>’s surviving historic<br />

urbanscape of outstanding universal<br />

significance, comprising of four<br />

precincts of Mehrauli, Nizamuddin,<br />

Shahjahanabad and New <strong>Delhi</strong>, that<br />

is being proposed for nomination as<br />

<strong>Delhi</strong>, a <strong>Heritage</strong> <strong>City</strong>.<br />

10<br />

State Party - INDIA INTACH- <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 11

DELHI: A HERITAGE CITY<br />

Nomination to UNESCO’s List of World <strong>Heritage</strong> Cities<br />

1<br />

Mehrauli<br />

The heritage precinct of Mehrauli<br />

is the site of the first capital city<br />

of <strong>Delhi</strong> and has seen 900 years of<br />

continuous habitation, leading to a<br />

layering of history which has resulted<br />

in a complex socio cultural mosaic.<br />

Continuous habitation in Mehrauli can<br />

be attributed to its strategic location<br />

on a ridge, providing much needed<br />

security, efficient water supply and good<br />

drainage due to the sloping landform,<br />

which meant liberation from diseases<br />

like malaria etc.<br />

The arrival of several Sufi saints in the<br />

early thirteenth century, in particular,<br />

Qutbuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki, has had a<br />

long-lasting impact on Mehrauli. During<br />

his lifetime the saint attracted followers<br />

to his khanqah or hospice, and after his<br />

death, his shrine continued to attract<br />

devotees. The site is also associated with<br />

the tradition of the Phoolwalon ki sair,<br />

that symbolizes secular harmony.<br />

The area being nominated as part of the<br />

World <strong>Heritage</strong> <strong>City</strong> of <strong>Delhi</strong> comprises<br />

of the original walled cities of Lal Kot<br />

and Qila Rai Pithora, extending south<br />

to include the traditional settlement<br />

of Mehrauli Village and the area<br />

presently identified as the Mehrauli<br />

Archaeological Park.<br />

Evolution of the historic precinct of<br />

Mehrauli<br />

Located on the spur of the Aravallis,<br />

Mehrauli has undulating landform<br />

with seasonal ponds visible in the<br />

various depressions. The unusual<br />

development of the site and its<br />

continuous habitation over an almost<br />

thousand year period can be attributed<br />

to its unique geographic location and<br />

landform.<br />

a<br />

Hindu and Muslim capitals of<br />

Mehrauli<br />

The oldest surviving traces of an<br />

urban settlement in Mehrauli, belongs<br />

to a small fort known as Lal Kot on<br />

the rocky ground of the ridge, built<br />

during the reign of the Tomar ruler<br />

Anangpal II, in the mid-eleventh<br />

century. Excavations suggest that<br />

there was already a settlement at<br />

this location, and there are literary<br />

references to an older name for the city<br />

– Yoginipur. Yet the bulk of the wealth<br />

of antiquities unearthed date from the<br />

Tomar period and after. The Jogmaya<br />

temple that stands there today consists<br />

of relatively new buildings but is also<br />

believed to be ancient. Surviving<br />

Tomar-era constructions include part<br />

of the fortification wall and a large<br />

tank, Anangtal, paved with dressed<br />

stone.<br />

b<br />

a. Map showing the early<br />

development of the Hindu and<br />

Muslims dynasties in Mehrauli.<br />

b. Within the fortified city of Lal<br />

Kot/ Rai Pithora were a large<br />

number of Hindu, Buddhist and<br />

Jain temples. Their pillars were<br />

later reused in the building of<br />

the Quwwat-ul Islam mosque.<br />

© ASI<br />

12<br />

State Party - INDIA

DELHI: A HERITAGE CITY Nomination to UNESCO’s List of World <strong>Heritage</strong> Cities Description of the Nominated Area<br />

a<br />

b<br />

c<br />

a<br />

The Chauhans who wrested power<br />

from the Tomars in the mid-twelfth<br />

century raised a defensive wall around<br />

the city, which had expanded beyond<br />

the walls of the citadel of Lal Kot and<br />

the newly fortified area was known as<br />

Qila Rai Pithora.<br />

In 1193, the Turks under Qutbuddin<br />

Aibak occupied <strong>Delhi</strong>, and the few<br />

decades there after saw a flurry of<br />

building activity within the fort.<br />

The congregational mosque, the<br />

remarkable Qutb Minar, the tomb of<br />

the ruler, Iltutmish are all testimony<br />

to the monumental works of the<br />

early Sultanate. Literary sources also<br />

describe a flourishing settlement<br />

within the walls of the city – with<br />

markets, mosques, madrasas (colleges)<br />

in addition to grand residences.<br />

The Sufi Bakhtiyar Kaki, popularly<br />

known as Qutb Sahib, came here in the<br />

early 13th century and is associated<br />

with many important structures to<br />

the south of Lal Kot. The saint is said<br />

to have had a very close relationship<br />

with Iltutmish (reigned 1211-36) and<br />

according to popular belief, Prophet<br />

Mohammad appeared in the dreams<br />

of both the Sultan and the saint,<br />

indicating the best spot at which to<br />

dig a tank to supply water to the city.<br />

Hauz-e-Shamsi was thus constructed<br />

in 1229, at a location south of the<br />

walled enclosure. The saint is said to<br />

have also offered prayers beside the<br />

tank in the company of his spiritual<br />

master, Muinuddin Chishti of Ajmer.<br />

Auliya Masjid was built at the spot<br />

on the eastern bank of the tank. The<br />

area in the vicinity of the tank became<br />

popular not only as a meeting place<br />

for the spiritually inclined, but also a<br />

popular burial site.<br />

When he died in 1235, the saint was<br />

buried closer to the city, just outside<br />

the walled city at the south-western<br />

corner. His burial site became an active<br />

and popular shrine, or dargah, which it<br />

remains to this day. It also became a<br />

centre for devotional music, performed<br />

at special gatherings called sama,<br />

which the saint in his own lifetime<br />

enjoyed. The immediate vicinity of the<br />

dargah too is dense with graves. The<br />

emperor Balban (1266-87) was buried<br />

here, just outside the walls of the fort.<br />

In addition to numerous graves and<br />

tombs, mosques, gardens and other<br />

structures have been added. These<br />

include the pavilion on the western<br />

bank (c. 1311) said to mark the spot<br />

where the prophet, seated on a horse,<br />

appeared to Iltutmish in a dream.<br />

Water management was an important<br />

consideration in settlement planning.<br />

Mehrauli is a prime example of proper<br />

utilization of the landform for water<br />

storage and distribution. The location<br />

of Hauz-i-Shamsi and the construction<br />

of baolis like Gandhak-ki-baoli and<br />

Rajon-ki-baoli illustrate this point.<br />

d<br />

a. The Chauhan’s extended<br />

the old citadel and the newly<br />

fortified area was called Qila<br />

Rai Pithora.<br />

b. Rajon ki Baoli constructed for<br />

water supply and management.<br />

c. Entrance of the sculpturous<br />

Qutb Minar<br />

d. Allaudin Khilji’s extension to<br />

the Qutb Complex.<br />

b<br />

a. Imposing Tomb of Adham<br />

Khan, AD 1562.<br />

b. Jahaz Mahal on the western<br />

banks of Hauz-i-Shamsi.<br />

c. Map showing developments<br />

from the Khilji and Mughal<br />

Periods.<br />

Khilji Dynasty - Mughal era<br />

After the Slave Dynasty, although Qila<br />

Rai Pithora was no longer the capital as<br />

Allaudin Khilji founded his own capital<br />

at Siri, a little to the north of Mehrauli,<br />

Allaudin Khilji still made extensions<br />

to the Qutb Complex and people<br />

continued to inhabit this older city of<br />

Qila Rai Pithora. The area south of the<br />

Qutb complex saw the construction<br />

of many buildings, well into the 16th<br />

century and the arrival of the Mughals.<br />

Located at the highest altitude on<br />

this site is the Takiya of Kamli Shah, a<br />

saint who arrived in the 14th C. The<br />

saint Maulana Jamali built a grand<br />

mosque in 1528-29, and was buried in<br />

a small but beautiful tomb next door.<br />

Several Lodi period tombs are to be<br />

found in this area including residential<br />

clusters. The Hauz-i-Shamsi was<br />

the main recreational area. On its<br />

western bank is the Jahaz Mahal, an<br />

impressive Lodi period building, that<br />

exemplifies the mature Sultanate<br />

style, reflecting a harmonious mix<br />

c<br />

of materials – grey quartzite, red<br />

sandstone, and glazed tiles; and forms<br />

– arches, domes, chhatris (domed<br />

kiosks) and corbelled doorways, that<br />

drew from both western Islamicate and<br />

Indian traditions. Structures similar<br />

to mosques, but oriented north-south<br />

also exist, for example Sohan Burj. The<br />

Dargah of Bakhtiyar Kaki continued to<br />

gain importance and several buildings<br />

were added to this complex, viz: Naubat<br />

Khana, Majlis Khana.<br />

Mughal period structures are to be<br />

found in this area including residential<br />

clusters. These range from the<br />

imposing tomb of Adham Khan (1562),<br />

to the elegant nineteenth century<br />

enclosure containing the graves of the<br />

Loharu family. Quli Khan (died early<br />

seventeenth century), the son of the<br />

Mughal emperor Akbar’s wet nurse<br />

and Chaumachi Khan are also buried<br />

here. The continued building activity<br />

in the area, even in the absence of the<br />

patronage of the royal court can be<br />

attributed largely to the presence of the<br />

Dargah of Bakhtiyar Kaki.<br />

14<br />

State Party - INDIA INTACH- <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 15

DELHI: A HERITAGE CITY Nomination to UNESCO’s List of World <strong>Heritage</strong> Cities Description of the Nominated Area<br />

Colonial Mehrauli<br />

Post Independence<br />

In the 19th century, with the British<br />

having taken control of Shahjahanbad,<br />

Mehrauli was again popular with the<br />

Mughals and they spent a lot more<br />

time here. The nineteenth century saw<br />

the growth of a thriving settlement to<br />

the west and south of the palace and<br />

the shrine and some grand residences<br />

were built around the Jogmaya temple,<br />

which are still in existence. The Bazaar<br />

spine developed with houses being<br />

built on both sides of what was then<br />

the main road to the town of Gurgaon<br />

and is today the Mehrauli Bazaar.<br />

As Mehrauli was reputed to have a<br />

healthier climate than Shahjahanabad,<br />

many of the rich of <strong>Delhi</strong> built second<br />

homes here and serais, havelis and<br />

dalan houses came up in the area.<br />

The gardens around the Hauz-e-<br />

Shamsi to the south became important<br />

recreational areas for this population.<br />

Jharna, a waterfall was created from an<br />

overflow of the tank, around which a<br />

formal garden was laid out in the 18th<br />

century. Rich game in the surrounding<br />

wilderness was an added attraction.<br />

In time development took place on<br />

both sides of the road all the way down<br />

to the Hauz-e-Shamsi, forming what is<br />

today called Mehrauli village.<br />

Among the graves next to the saint’s<br />

shrine are those of the Mughal royal<br />

family, dating from the eighteenth and<br />

nineteenth centuries; and in the first<br />

half of the nineteenth century a royal<br />

palace came up close to these, built by<br />

the emperors Akbar II (1806-37) and<br />

Bahadur Shah II (1837-57).<br />

In the mid-nineteenth century,<br />

following the banishment of the<br />

Mughal monarch, Bahadur Shah Zafar<br />

to Rangoon (1858), Mehrauli became<br />

a tehsil headquarter and many offices<br />

and government buildings were<br />

set up here. The central spine was<br />

a<br />

developed during this period. Most<br />

of the development was within the<br />

settlement itself.<br />

There was some colonial intervention<br />

in the northern section by individuals<br />

like Thomas Metcalfe, the highest<br />

British administrative official in <strong>Delhi</strong>.<br />

He modified the tomb of Quli Khan to<br />

create a weekend home, Dilkusha, also<br />

adapting and adding other buildings,<br />

and laying out a garden. He also<br />

created some singular buildings, e.g.<br />

two stepped pyramid-like structures,<br />

and a couple of domed stone canopies<br />

in the tradition of the English folly.<br />

By the twentieth century the southern<br />

area had ceased to be populated and<br />

buildings lower in the valley had been<br />

partly buried in the silt brought down<br />

by the stream coming from the Hauze-Shamsi.<br />

Among these sprawling<br />

palaces of the Mughals many town<br />

houses, offices and other structures<br />

were built by the British in the colonial<br />

style, giving it a distinct colonial flavour.<br />

b<br />

a. Map showind Colonial interventions<br />

in Mehrauli<br />

b. British repairs and additions<br />

to the tower in the 1820s included<br />

a cupola and sandstone<br />

railings on the balconies.<br />

b<br />

a<br />

a. Map showing the postindependence<br />

development in<br />

Mehrauli.<br />

b. View of Jamali Kamali.<br />

While the capital city, its historic and<br />

iconic buildings are conserved and<br />

linked through trails and interpretative<br />

signage, Mehrauli village with the<br />

dargah as its focus, is still a living<br />

settlement that has survived for over<br />

900 years. The link between the Dargah<br />

of Qutb Sahib and the Hauz-e-Shamsi<br />

continues till today as the trail of the<br />

Phoolwalon ki sair or ‘festival of the<br />

flower sellers’. Arising out of avow<br />

taken by the wife of Akbar II, Mumtaz<br />

Mahal, that she would offer a coverlet of<br />

flowers at the dargarh of Qutb Sahib if<br />

her son returned from the exile imposed<br />

by the British government, it became a<br />

tradition that has survived to this day.<br />

Floral offerings, in particular pankhas<br />

or fans were assembled around the<br />

Jharna near the hauz, and then carried<br />

to the dargah to be offered at the saint’s<br />

grave. Pankhas were also offered at the<br />

Hindu temple of Jogmaya, believed to<br />

be a sacred site of great antiquity. This<br />

celebration of Hindu-Muslim amity<br />

is a tradition that has survived to the<br />

present time, and is an annual festival<br />

at Mehrauli.<br />

16<br />

State Party - INDIA INTACH- <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 17

DELHI: A HERITAGE CITY<br />

Nomination to UNESCO’s List of World <strong>Heritage</strong> Cities<br />

2<br />

Nizamuddin<br />

Nizamuddin has been associated with<br />

the presence of the renowned Sufi<br />

saint Sheikh Nizamuddin Auliya since<br />

c 1270 AD and has drawn various<br />

people to this area– a multitude of<br />

devout followers of Sufism, as well<br />

as, poets, noble men and even kings<br />

and emperors visited the saint when<br />

he was alive and even after his death.<br />

Even today, almost 700 years after his<br />

death, pilgrims visit the shrine of the<br />

saint Nizamuddin Auliya.<br />

Since it was considered auspicious to<br />

be buried near a saint’s grave, many<br />

of the saint’s ardent followers were<br />

finally laid to rest in the vicinity of the<br />

Sufi shrine. Seven centuries of tomb<br />

building can be seen in the Nizamuddin<br />

precinct.<br />

a<br />

The area being nominated as part<br />

of the World <strong>Heritage</strong> <strong>City</strong> of <strong>Delhi</strong><br />

consists of the traditional settlement<br />

that grew around the dargah of the<br />

saint, and the Nizamuddin precinct.<br />

The northern limit of the settlement<br />

is Lodi Road; while the Barahpullah<br />

nallah, a tributary of the Yamuna,<br />

marks the western and southern edge<br />

of the dargah settlement. To its east is<br />

Mathura Road.<br />

The Nizamuddin Precinct is the area<br />

which has as its southern limit, the<br />

dargah settlement and stretches right<br />

up to Purana Qila in the north, and in<br />

the other direction, from <strong>Delhi</strong> Golf<br />

Club to the west, right down to the<br />

banks of the river to the east.<br />

b<br />

a. View from the top of<br />

Humayuns Tomb showing the<br />

Nizamuddin Dargah in the<br />

background.<br />

b. Map of Nizamuddin showing<br />

extent of development in the<br />

precinct.<br />

18<br />

State Party - INDIA

DELHI: A HERITAGE CITY Nomination to UNESCO’s List of World <strong>Heritage</strong> Cities Description of the Nominated Area<br />

a<br />

b<br />

b<br />

Evolution of the Nizamuddin Dargah<br />

Settlement<br />

c<br />

It is believed that Ghiasuddin Balban<br />

built a palace, the Lal Mahal, at a site<br />

which was the suburb of the city of<br />

Hazrat <strong>Delhi</strong>, in the mid-13th century,<br />

following which the area came to be<br />

known as Ghiaspur. The site had the<br />

river flowing immediately to its east,<br />

agricultural land all the way up to<br />

the village of Indrapat located to its<br />

north and the city of Kilokhari to its<br />

southeast.<br />

Lal Mahal was a fine structure with<br />

a central dome and arches, and is<br />

the earliest surviving example of a<br />

Sultanate era palace. It can stake claim<br />

to be the first building where a true<br />

arch and dome were used.<br />

From 1265 AD, when Ghiasuddin<br />

Balban ascended the throne, there is<br />

evidence of a settlement, at Ghiaspur.<br />

Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya, a much<br />

revered Sufi saint, chose this settlement<br />

to establish his khanqah.<br />

The wall that encircled the settlement<br />

was believed to have been built at the<br />

same time as the Lal Mahal (c 1265 AD).<br />

The enclosure was irregular in shape<br />

with circular bastions at intervals<br />

and topped with battlements. A grand<br />

mosque, the Jamaat Khana was built<br />

here during Alauddin Khilji’s reign(AD<br />

1295-1315). Saint Nizamuddin Auliya,<br />

meditated at a spot along the river and<br />

a chillagah was built at the site which is<br />

adjacent to the site where Humayun’s<br />

Tomb came up two centuries later.<br />

The presence of Nizamuddin Auliya<br />

resulted in many people choosing<br />

to live in this settlement or visit this<br />

area to pay homage to him. A baoli<br />

was added in AD 1320, to serve the<br />

needs (drinking water) of the local<br />

community and pilgrims and also for<br />

wuzu (ablutions) prior to prayers at<br />

the mosque, indicating that by this time<br />

there was already a large population in<br />

Ghiaspur and an even larger volume of<br />

pilgrims. After the death of Nizamuddin<br />

Auliya, he was buried in the courtyard<br />

of the Jamaat Khana mosque and the<br />

village of Ghiaspur came to be known<br />

as ‘Nizampur’. Within six months of the<br />

death of the saint, his favourite disciple,<br />

the great poet, Amir Khusro too died,<br />

unable to bear the grief of the loss of<br />

his spiritual master and was buried<br />

within the complex.<br />

d<br />

Later during the<br />

Mughal period, the<br />

area surrounding<br />

the baoli of Hazrat<br />

Nizamuddin Auliya<br />

was built up with the<br />

southern arcade dating<br />

from AD 1379-80.<br />

a. Lal Mahal, Nizamuddin<br />

Dargah Settlement<br />

b. The part facade of Jamaat<br />

Khana mosque in the<br />

Nizamuddin Dargah Settlement.<br />

c. Map showing early<br />

developments in the<br />

Nizamuddin Dargah settlement<br />

d. Baoli within the Nizamuddin<br />

Dargah Settlement<br />

a. Map showing Sultunate<br />

period developments in<br />

the Nizamuddin Dargah<br />

settlement.<br />

a<br />

b. Map showing Suri<br />

period developments in<br />

the Nizamuddin Dargah<br />

A Kot abutting the walled settlement to<br />

the south was constructed in the mid<br />

14th century. Two major structures<br />

that still survive here were built during<br />

the Tughlaq period, Kalan Masjid<br />

in AD 1370-1 and the tomb of Khan<br />

Jahan Junan Shah Tilangani, the Prime<br />

Minister of Firoz Shah Tughlaq, located<br />

within the Kot is the earliest octagonal<br />

tomb in India.<br />

The main spine or the major<br />

thoroughfares connect the main gates<br />

of the settlement to the main elements<br />

within the settlement identified as<br />

the dargah, the bazaar, the kot and<br />

Kalan Masjid. The earliest road in the<br />

settlement led from the north gate of<br />

the village enclosure connecting the<br />

dargah to the north eastern gate of the<br />

Kot through the bazaar street. A later<br />

development was the road intersecting<br />

it at right angles just outside the north<br />

eastern gateway to the Kot giving access<br />

to the Kalan Masjid and the Imambara<br />

and leading from the eastern gateway<br />

to the south western gateway of the<br />

village enclosure (perhaps the route of<br />

the Tazia procession) The main direct<br />

b<br />

access to the dargah was from the north<br />

western gateway but the dargah was<br />

also connected through the eastern<br />

gateway of Amir Khusro’s enclosure.<br />

Building activity in the area continued<br />

through the Lodi period and some<br />

surviving structures built during this<br />

period are the Barahkhambha, Gol<br />

Gumbad and Do Sirihya Gumbad.<br />

Urban morphology<br />

Within the walled enclosure was an<br />

intricate pattern of streets, galis and cul<br />

de sacs, all at a pedestrian, human scale.<br />

A network of narrow Mohalla streets<br />

or galis provides access and linkages<br />

to the main quarters and houses. These<br />

were used mainly by people of the<br />

mohalla. These narrow galis ended in<br />

cul-de-sacs, owned and shared by the<br />

users. The galis are characterised by<br />

varying widths and periodic changes<br />

in direction. The urban morphology<br />

is characterised by streets with<br />

changing levels and ramps or steps,<br />

varying building heights and entrance<br />

doorways.<br />

20<br />

State Party - INDIA INTACH- <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 21

DELHI: A HERITAGE CITY Nomination to UNESCO’s List of World <strong>Heritage</strong> Cities Description of the Nominated Area<br />

b<br />

a<br />

c<br />

a<br />

c<br />

d<br />

Later during the Mughal period, the<br />

area surrounding the baoli of Hazrat<br />

Nizamuddin Auliya was built up with<br />

the southern arcade dating from AD<br />

1379-80. In the 16th century, the Grand<br />

Trunk Road which stretched from the<br />

eastern end of India to Peshawar and<br />

beyond in the west, passed through<br />

the Nizamuddin area. Thus with the<br />

river along its eastern edge and the GT<br />

Road passing through it, Nizamuddin<br />

was located on major medieval<br />

transport arteries, which enhanced its<br />

importance.<br />

The tomb of Bai Kokaldai, standing<br />

on the western edge of Hazrat<br />

Nizamuddin Baoli was built later in AD<br />

1541. Atgah Khan, ‘who was present<br />

when Humayun was defeated by Sher<br />

Shah Sur and aided the emperor in<br />

his escape from the field of battle’ was<br />

buried in AD 1566-7, in close proximity<br />

to the tomb of Hazrat Nizamuddin<br />

Auliya. His jewel like tomb is covered<br />

with a unique inlay of tile work in<br />

marble. The emperor Shahjahan’s<br />

daughter Jahanara, who died in 1681<br />

was also buried here followed by the<br />

emperor Muhammad Shah who died in<br />

1748. In the 19th century prominent<br />

buildings such as the dalan of Mirdha<br />

Ikram (1801) and the grave enclosure<br />

of Mirza Jahangir (son of Akbar II)<br />

who died in 1832 were also added to<br />

the grave enclosure. The famous 19th<br />

century poet Mirza Ghalib was also<br />

buried in close proximity of Chausath<br />

Khamba.<br />

By this point other movement networks<br />

developed like Ghalib Road which led<br />

from an entrance in the north eastern<br />

enclosure wall of Chausath Khamba and<br />

Urs Mahal enclosure where qawwalis<br />

were held during Urs. Another road<br />

from the eastern enclosure walls to the<br />

dargah area past Chausath Khamba<br />

leads from Humayun’s Tomb and Arabki-serai<br />

complex.<br />

Bazaar Street<br />

A unique character of the main street<br />

leading from the main chowk to the<br />

dargah was that of a chatta street<br />

with flower sellers and items of<br />

worships. The 14th century structures<br />

had a high projecting stone plinth,<br />

a. Map showing Mughal<br />

period developments in the<br />

Nizamuddin Dargah settlement.<br />

b. Dargah of the Sufi saint<br />

Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya<br />

c. Tomb of Khan Jahan Junan<br />

Shah Tilangani<br />

d. Barakhamba on the outskirts<br />

of the Nizamuddin settlement.<br />

b<br />

a. Marble Jalis inside Chausath<br />

Khamba.<br />

b. Randon rubble masonry core<br />

with red sandstone jalis.<br />

c. Chausath Khamba.<br />

pointed arched openings in rubble<br />

masonry walls plastered over and lime<br />

washed. Adjacent to the 14th century<br />

structures, the later Mughal structures<br />

followed the same building module but<br />

with different detailing.<br />

Building Materials and Construction<br />

Technology<br />

Different materials were used for<br />

different structures. The most<br />

commonly used building material<br />

was the <strong>Delhi</strong> quartzite; red, yellow<br />

and spotted sandstone and Lakhauri<br />

bricks. More elaborate buildings had<br />

marble, a variety of decorative stone<br />

and tiles. The load bearing walls were<br />

up to 50 cms in thickness and were<br />

built with an inner core of irregular<br />

stone with dressed quartzite or<br />

sandstone facing. Some walls were<br />

plastered with up to 5 cm of Lime<br />

Plaster. Examples are also found of dry<br />

dressed stone masonry, held together<br />

with iron clamps. The walls were<br />

spanned over with vaults, domes and<br />

arched systems. The most commonly<br />

seen vaults were the cloister and cradle<br />

and groin vaults spanning 1.5 - 4.0<br />

m widths. Domes were supported on<br />

squinches and pendentives. Often the<br />

roof was of sandstone slabs spanning<br />

the beams supported on sandstone<br />

brackets that projected from the wall.<br />

Over the roof, dry sand was compacted<br />

and finished over with lime plaster to<br />

give a flat, usable terrace. Side walls<br />

were projected to form a parapet for<br />

the terrace.<br />

Residential quarters<br />

Dwelling units varied from the havelis<br />

of prominent persons to single roomed<br />

units of the poor. The Mughal period<br />

havelis varied from two to three storeys<br />

in height, had several courtyards<br />

including one at the entrance, and<br />

incorporated jalis( screens) in windows<br />

and balconies. Elaborate arched<br />

entrance doorways gave access from<br />

the street outside into the courtyard.<br />

Enclosing the courtyards were single<br />

storied arched dalans. The havelis were<br />

often decorated with fine late Mughal<br />

moulded and incised plaster decoration.<br />

22<br />

State Party - INDIA INTACH- <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 23

DELHI: A HERITAGE CITY Nomination to UNESCO’s List of World <strong>Heritage</strong> Cities Description of the Nominated Area<br />

Nizamuddin Precinct<br />

During the Sayyoid and Lodi period in<br />

the 15th and 16th centuries, there was<br />

a spate of tomb building in the vicinity<br />

of the saint’s dargah, even though<br />

some of the significant royal tombs of<br />

these two dynasties were built almost<br />

a mile east of the Dargah of Hazrat<br />

Nizamuddin Auliya.<br />

The immediate precinct of the<br />

dargah settlement saw the maximum<br />

development with the coming of the<br />

Mughals in 1526, who built a number<br />

of garden tombs. The area boasts of<br />

some of the earliest buildings of the<br />

Mughal dynasty. Nila Gumbad (blue<br />

domed structure) is certainly the<br />

earliest building built by the Mughals<br />

in <strong>Delhi</strong>. Located a few yards south<br />

of Hazrat Nizamuddin’s chillagah, on<br />

a river island, the dome, its tile work<br />

and plasterwork are all reminiscent of<br />

Persian influence. Another tomb, the<br />

Sabz Burj, literally ‘green dome’, now<br />

standing in a traffic island on Mathura<br />

Road is contemporary to Nila Gumbad<br />

and pre-dates Humayun’s Tomb.<br />

Emperor Humayun chose to build his<br />

capital city, Dinpanah or ‘refuge of the<br />

faithful’, north of Hazrat Nizamuddin’s<br />

Dargah in 1533. The city walls had<br />

barely been built when Humayun was<br />

ousted in 1540, by Sher Shah Sur who<br />

continued to build the fortifications<br />

and the citadel, now known as Purana<br />

Qila or Old Fort. Sher Shah also built<br />

the striking Qila-i-Kohna Mosque<br />

within the citadel.<br />

Isa Khan Niyazi, a nobleman at the<br />

court of Sher Shah Sur, was buried in<br />

the immediate vicinity of the dargah<br />

settlement in an octagonal garden<br />

enclosure in AD 1547-8. Isa Khan<br />

Niyazi’s Tomb enclosure was the<br />

culmination of the octagonal style of<br />

tomb building. It also has the earliest<br />

sunken garden in India pre-dating<br />

Emperor Akbar’s tomb in Sikandra,<br />

Agra - the most famous existent<br />

example - by over a century.<br />

A small tomb, locally known as the<br />

Barber’s Tomb, now standing within<br />

the walled enclosure of Humayun’s<br />

Tomb, pre-dates Humayun’s Tomb, and<br />

displays local architectural traditions<br />

–red-white contrast using sandstone<br />

and marble - used earlier at Alai<br />

Darwaza and Ghiasuddin Tughlaq’s<br />

tomb. Humayun’s Tomb was built<br />

between the River Yamuna on its east<br />

and the Grand Trunk road to its west,<br />

in the 1560s by his son, the great<br />

Emperor Akbar. The tomb standing<br />

within a walled garden enclosure of 26<br />

acres, is the first of the grand dynastic<br />

mausoleums that were to become<br />

synonyms of Mughal architecture. This<br />

architectural style reached its zenith<br />

many decades later at the later Mughal<br />

tomb, the Taj Mahal.<br />

Humayun’s Tomb dwarfs any tomb<br />

built in <strong>Delhi</strong> during the three centuries<br />

of Muslim rule that preceded the<br />

Mughals. Never before in the Islamic<br />

world had a tomb been built on such<br />

scale, with red sandstone and white<br />

marble. The architect, Mirak Mirza<br />

Ghiyath, of Persian descent, who came<br />

from Herat in present day Afghanistan,<br />

used the red-white contrast to great<br />

effect with white ‘marble-like’ lime<br />

plaster covering portions of the façade<br />

that were not clad with stone such<br />

as the faces of lower niches and the<br />

domes of the four comer canopies.<br />

Humayun’s Tomb remained a place of<br />

pilgrimage for the Mughal emperors<br />

Akbar, Jahangir, Shahjahan who made<br />

frequent visits to pay their respects.<br />

Humayun’s garden-tomb is also called<br />

the ‘dormitory of the Mughals’ as in the<br />

cells are buried over 150 members of<br />

the Mughal family, all in un-inscribed<br />

graves in the lower cells.<br />

a<br />

b<br />

a. Khairpur Tomb now in Lodi<br />

Garden © ASI<br />

b. Rahim’s Tomb<br />

a b c<br />

d<br />

a. Arab ki Sarai<br />

b. Sunderwala Burj<br />

c. Humayuns Tomb with Barber’s<br />

Tomb in the foreground<br />

d. Facade of Nila Gumbad<br />

While Humayun’s Tomb was being built,<br />

just outside the western enclosure<br />

wall, two significant buildings - a tomb<br />

and a three bay wide mosque - known<br />

as Afsarwala Tomb and Mosque were<br />

also being constructed. It is not known<br />

who commissioned these or if they<br />

stood in an independent enclosure.<br />

Haji Begum brought with her three<br />

hundred Arabs from her pilgrimage to<br />

Mecca, and the ‘Arab Serai’ was built to<br />

house these families.<br />

It was during the early Mughal era<br />

and Emperor Akbar’s reign, following<br />

the building of Humayun’s Tomb, that<br />

several prominent structures were<br />

built in the Nizamuddin area. Important<br />

16th / early 17th century structures<br />

included the enclosed garden tombs of<br />

Bu Halima, ‘Batashewala’ Complex and<br />

the ‘Sunderwala’ complex.<br />

It is not known who ‘Bu Halima’ was<br />

but her tomb is entered through a<br />

lofty gateway standing opposite the<br />

western gateway of the Humayun’s<br />

Tomb complex, off-center to her own<br />

tomb , suggesting it dates from just<br />

after the building of Humayun’s Tomb.<br />

The tomb of Muzaffar Husain Mirza,<br />

grand-nephew of Emperor Humayun<br />

was built in AD 1603 and is today<br />

known as Bara Batashewala Mahal.<br />

Another tomb, now known as Chotta<br />

Batashewala stands alongside<br />

Muzaffar Husain Mirza’s tomb.<br />

The ‘Sunderwala complex’, another<br />

tomb- garden enclosure, includes the<br />

two tombs now known as Sunderwala<br />

Burj and Sunderwala Mahal and though<br />

it is today unknown who these were<br />

built for, the architectural style and the<br />

ornamentation contained within date<br />

these to the 16th/17th century, i.e., the<br />

early Mughal era. ‘Sunderwala Mahal’ is<br />

the only other example of a square tomb<br />

chamber surrounded by eight rooms<br />

with five half-domed openings on each<br />

façade. A few hundred yards north of<br />

the Arab Serai was another Mughal<br />

Serai, known as Azimganj, within the<br />

area today occupied by Government<br />

Sundar Nursery.<br />

Over half a century after the building<br />

of Humayun’s Tomb, the tomb of Khani-Khanan<br />

Abdur Rahim Khan, the son<br />

of Bairam Khan, who was the tutor of<br />

Emperor Akbar was built a few hundred<br />

yards south of Humayun’s Tomb.<br />

Through the 18th and 19th centuries,<br />

tomb building continued in the vicinity<br />

but large garden-tombs were followed<br />

by only smaller structures such as those<br />

dotting the <strong>Delhi</strong> Golf Club.<br />

24<br />

State Party - INDIA INTACH- <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 25

DELHI: A HERITAGE CITY Nomination to UNESCO’s List of World <strong>Heritage</strong> Cities Description of the Nominated Area<br />

3<br />

Shahjahanabad Zone<br />

(Mid seventeenth century)<br />

The walled Shahjahanabad is the<br />

capital city established by the Mughal<br />

Emperor Shahjahan, under whom<br />

Mughal architecture reached its<br />

apogee. An important part of the city<br />

was the palace fortress now called the<br />

Red Fort; Around this palace complex<br />

was built a grand walled city, named<br />

Shahjahanabad (literally ‘established<br />

by Shahjahan’) after its royal founder.<br />

The layout of Shahjahanabad was<br />

influenced by ancient Hindu texts as<br />

well as medieval Persian traditions.<br />

A salient feature of this walled city is<br />

that though the pattern of land use was<br />

totally urban, it was still essentially a<br />

pedestrian city retaining a human scale.<br />

The residential areas were developed<br />

as introvert spaces, as independent<br />

social and environmental entities, while<br />

commercial activities grew along the<br />

spines, closer to areas of administrative<br />

a<br />

or institutional importance.<br />

The original extent of the city as<br />

designed during the Mughal period<br />

forms part of the core area proposed for<br />

Nomination as the World <strong>Heritage</strong> <strong>City</strong><br />

of <strong>Delhi</strong>.<br />

Traditional <strong>City</strong> Planning<br />

The choice of site appears to have been<br />

dictated by the availability of high<br />

land on the western bank of the River<br />

Yamuna and the natural protection<br />

provided by triangle formed by the<br />

two arms of the Aravalli ranges known<br />

as the Jhojla and Bhojla Paharis and<br />

the River Yamuna. Geographically, the<br />

location was ideal, not only from the<br />

point of view of protection but also as a<br />

convergence of important land routes.<br />

The city of Shahjahanabd comprises<br />

of an encircling city wall, more than<br />

8 kilometers long, and pierced by a<br />

number of gates and wickets. Built<br />

in the late seventeenth century, the<br />

city form has survived with relatively<br />

a<br />

minor change to the present times.<br />

The Manasara, one of the Hindu texts<br />

on architecture collectively called<br />

the Vastu Shastra, prescribes a bowshaped<br />

form for a city on a river, and<br />

this is the plan that Shahjahanabad<br />

roughly followed. The eastern wall of<br />

the city, parallel to the river, could be<br />

viewed as the string of the bow, and<br />

parallel to this ran the main northsouth<br />

street, linking the Kashmir gate<br />

in the north with the <strong>Delhi</strong> gate in the<br />

south. The other main street of the city<br />

could be viewed as the arrow placed<br />

in the bow, running from the main<br />

entrance to the Red Fort (which was<br />

located approximately midway along<br />

the eastern wall of the city) westwards<br />

to the Fatehpuri mosque. The palace<br />

complex therefore stood at the junction<br />

of the main north-south and east-west<br />

axes, where in the Hindu text a temple<br />

would have been located.<br />

b<br />

c<br />

a. Map of Shahjahanabad showing<br />

the natural features and lie<br />

of the land.<br />

b. Turkman Gate<br />

c. Kashmiri Gate<br />

26<br />

State Party - INDIA INTACH- <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 27

DELHI: A HERITAGE CITY Nomination to UNESCO’s List of World <strong>Heritage</strong> Cities Description of the Nominated Area<br />

In this arrangement the main<br />

congregational mosque of the city, the<br />

Jama Masjid, was located on a height<br />

fairly close to the palace complex, but<br />

off-centre with regard to the main<br />

streets. In terms of Persian texts such<br />

as the Rasa’il-e-Ikhwan-us-Safa, which<br />

viewed ideal city plans as mirroring<br />

the anatomy of man, the Jama Masjid<br />

would be the heart in relation to the Red<br />

Fort which was the head, and the eastwest<br />

street which was the backbone.<br />

The plan of Shahjahanabad therefore<br />

clearly shows both Hindu and Persian<br />

Sufi influences, in keeping with the<br />

long <strong>Delhi</strong> tradition of synthesis, and<br />

the general Mughal polity of liberality<br />

and inclusion vis a vis Hindu subjects.<br />

Key Architectural Elements<br />

The foundation of Red Fort was laid<br />

in 1639, and the emperor entering<br />

it ceremonially in 1648. After the<br />

erection of the Red Fort, the first<br />

feature, Fatehpuri Masjid, was erected<br />

in 1650 by the begum of Shahjahan one<br />

mile due west of the palace’s Lahore<br />

gate.<br />

Soon thereafter, she began the second,<br />

private gardens some 54 acres to the<br />

north of the pathway leading from Lal<br />

Qila to Fatehpuri Masjid.<br />

This ceremonial pathway developed<br />

into the third element, Chandni Chowk,<br />

where bullion merchants and other<br />

important men took up residence and<br />

maintained retail outlets. Important<br />

public buildings were located along it<br />

among them the kotwali(main police<br />

station), Sunehri Masjid, a mosque<br />

built in 1721-22 by a nobleman and<br />

a caravanserai. The Emperor rode in<br />

state along it every Friday to pray at<br />

Fatehpuri Masjid and thus the path<br />

became a ceremonial mall. A branch of<br />

River Yamuna ran down the middle and<br />

with large canopied trees alongside<br />

and footbridges over the canal it<br />

became the favorite gathering place in<br />

evening and on festive occasions.<br />

a<br />

This ceremonial street was divided into<br />

three sections by two historic squares.<br />

The one nearest to the fort was<br />

originally called Kotwali Chowk, but is<br />

today known popularly as Phawwara<br />

chowk after the phawwara or fountain<br />

established here in the 1870s. The<br />

chowk is associated with important<br />

episodes in the history of the city and<br />

of the Mughal Empire. The Gurudwara<br />

Sisganj on this chowk marks the spot<br />

of the execution of Guru Teg Bahadur;<br />

the 9th Guru of the Sikhs who was<br />

put to death in 1675 on the orders of<br />

the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb for<br />

his attempts to found an independent<br />

Sikh state. Also, it was on the steps of<br />

Sunehri Masjid that the Persian invader<br />

Nadir Shah sat in 1739 to witness the<br />

massacre of the populace of the city<br />

that he had ordered. The area north<br />

of Chandni Chowk remained as large<br />

private estates of the nobility, with<br />

the exclusion of the north-west sector,<br />

where a spatial pattern similar to that<br />

south of Chandni Chowk prevailed.<br />

b<br />

a. Map of Shahjahanabad showing<br />

the location of buildings<br />

before the walled city was built.<br />

b. Chandni Chowk was an<br />

important thoroughfare with<br />

shops lining the roads and<br />

residences above, interspersed<br />

with chowk (squares), gateways<br />

to mansions and lanes.<br />

© British Library<br />

a<br />

a<br />

b<br />

a. Map of Shahjahanabad<br />

showing the main axis and the<br />

key features.<br />

b. The Jama Masjid at <strong>Delhi</strong>.<br />

from the north-east.<br />

© British Library<br />

b<br />

Between 1644 and 1658 Shahjahan<br />

built a great mosque, Jama Masjid( the<br />

fourth landmark) about one-half mile<br />

southwest of the principal palace gate.<br />

It became the congregational mosque<br />

of the city, and continues today to orient<br />

visually because it lies upon a rocky<br />

outcrop above the general plain of the<br />

city. The emperor himself appointed its<br />

functionaries and paid for its upkeep<br />

out of the royal exchequer. A relatively<br />

short but important street connected<br />

the south gate of the palace fortress to<br />

this mosque. The function of the street<br />

as a route for ceremonial processions<br />

was continued into British colonial<br />

times. On occasions like the durbars,<br />

the state procession went from the Red<br />

Fort past the Jama Masjid into Chandni<br />

Chowk. At other times this street, all<br />

the way up to the steps of the mosque,<br />

was a lively social space thronging with<br />

purveyors of exotic goods, street foods,<br />

story tellers and street performers.<br />

The fifth feature is Faiz Bazaar, a<br />

leisure mall that developed between<br />

<strong>Delhi</strong> Gate of the palace and <strong>Delhi</strong><br />

Gate in the city wall. In later years, this<br />

became the principal north-south route<br />

through the city connecting Civil Lines<br />

and New <strong>Delhi</strong>. To the east of this street<br />

lies Daryaganj, literally ‘the mart by<br />

the river’, where grain and other goods<br />

were unloaded from boats plying on the<br />

River Yamuna.<br />

The last nodal element is Qasi Hauz,<br />

the main water reservoir, situated at<br />

the junction of four important bazaars.<br />

These six elements, in conjunction with<br />

the locations of the city gates, yield<br />

clues to the hierarchical structure of<br />

the existing street pattern and spatial<br />

distribution of the population<br />

Urban Morphology<br />

The formal geometry of the walled city<br />

governed by the strategic location of<br />

the six key architectural elements was<br />

not followed in the rest of the walled<br />

city. Nor was the formal hierarchy of<br />

space attempted in these areas. The<br />

city’s strategic location and defensive<br />

perimeter attracted residents from the<br />

older and less secure settlements to the<br />

south so that the quadrant bounded<br />

by Chandni Chowk, Faiz Bazaar, and<br />

the city wall was built up. Thus a basic<br />

network of five major arterials leading<br />

from the six key elements and other<br />

gates to different parts of the walled city<br />

were built as spines of major activity.<br />

Paths linking the gates in the city<br />

walls to Fatehpuri Masjid, Qasi Hauz,<br />

Jama Masjid and Kalan Masjid(built by<br />

emperor Firoz Shah in 1386) became<br />

definite streets and finally important<br />

bazaars.<br />

All the streets, apart from formally<br />

laid Chandni Chowk, twist and turn,<br />

providing visual enclosure as well as<br />

a sequence of experiences. The ‘street’<br />

was treated as an extension of activity<br />

spaces in addition to its function as a<br />

spaces in addition to its function as a<br />

corridor of movement. The junction of<br />

two streets automatically formed into a<br />

28<br />

State Party - INDIA INTACH- <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 29

DELHI: A HERITAGE CITY Nomination to UNESCO’s List of World <strong>Heritage</strong> Cities Description of the Nominated Area<br />

‘chowk’ often for a pause in movement<br />

and for better communication.<br />

terrace development, but maintaining<br />

distinctly separate identities.<br />

The other streets were of a significantly<br />

lower hierarchy and these were built<br />

mainly as access roads to the residential<br />

areas. In most cases, the access roads<br />

would not provide through routes,<br />