Potatoes⦠- Bayer CropScience

Potatoes⦠- Bayer CropScience

Potatoes⦠- Bayer CropScience

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

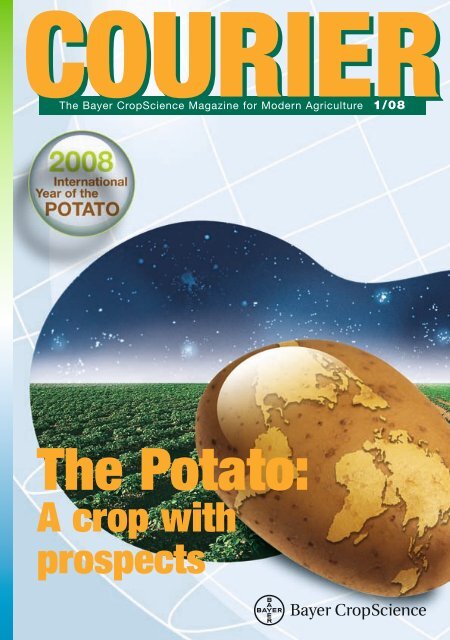

COURIER<br />

The <strong>Bayer</strong> <strong>CropScience</strong> Magazine for Modern Agriculture 1/08<br />

The Potato:<br />

A crop with<br />

prospects

Contents<br />

2 Asia is the new continent for<br />

potatoes<br />

6 <strong>Bayer</strong> <strong>CropScience</strong> supports<br />

China’s potato development<br />

8 The potato – versatile<br />

and nutritious<br />

12 The UK Potato Project –<br />

Participation that paid off<br />

14 ‘Innovation and knowledge<br />

determine our success’<br />

18 Phytophthora infestans is<br />

becoming increasingly<br />

aggressive<br />

21 New combination of active<br />

substances against potato blight<br />

22 Colorado beetle and aphids –<br />

threatening, but manageable<br />

26 Potatoes…<br />

from Peru to the world<br />

28 Potato starch –<br />

a versatile commodity<br />

Asia is the<br />

new contine<br />

for potatoes<br />

Published by: <strong>Bayer</strong> <strong>CropScience</strong> AG, Monheim / Editor:<br />

Bernhard Grupp / With contributions from: Agroconcept<br />

GmbH, K. Doughty, S. Rudolph, A. Schirring, C. Wang,<br />

M. Wiedenau / Design and Layout: Xpertise, Langenfeld /<br />

Litho graphy: LSD GmbH & Co. KG, Düsseldorf / Printed by:<br />

Dynevo GmbH, Leverkusen / Repro duction of contents is<br />

per missible providing <strong>Bayer</strong> is acknowl edged and advised<br />

by specimen copy / Editor’s address: <strong>Bayer</strong> <strong>CropScience</strong><br />

AG, Corporate Commu ni cations, Alfred-Nobel-Str. 50,<br />

40789 Monheim am Rhein, Germany, FAX: 0049-2173-<br />

383454 / Website: www.bayercropscience.com<br />

Forward-Looking Statements<br />

This publication may contain forward-looking statements<br />

based on current assumptions and forecasts made by<br />

<strong>Bayer</strong> Group or subgroup management. Various known and<br />

unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors could lead<br />

to material differences between the actual future results,<br />

financial situation, development or performance of the<br />

company and the estimates given here. These factors<br />

include those discussed in <strong>Bayer</strong>’s public reports which are<br />

available on the <strong>Bayer</strong> website at www.bayer.com. The<br />

company assumes no liability whatsoever to update these<br />

forward-looking statements or to conform them to future<br />

events or developments.<br />

Today, the potato is grown in 130 countries,<br />

on all continents of the world. Asia<br />

und Oceania have now overtaken Europe<br />

as the world’s most important producers. In<br />

2007, 320 million tonnes of potatoes were<br />

harvested from around 19.2 million ha of<br />

land around the world. The areas of greatest<br />

production are Asia (8.7 million ha under<br />

cultivation) and continental Europe<br />

(7.4 million ha). Within the latter region,<br />

cultivation is concentrated in the Russian<br />

Federation, the European Union, and the<br />

Ukraine.<br />

During the last two decades, potatogrowing<br />

has declined in developed countries,<br />

but it has seen an increase in developing<br />

countries and newly-industrialising<br />

countries – particularly in Asia. This<br />

change has resulted not only from an<br />

extension of the area under cultivation,<br />

but also through a broader inclusion of<br />

potatoes in the rotation system, which has<br />

been made possible by the availability of<br />

early-ripening varieties. With a vegetative<br />

period of 80 to 100 days, these varieties<br />

fit well into cultivation gaps between<br />

traditional crops, for example between rice<br />

and wheat in India.<br />

The cultivation methods used in developing<br />

countries and newly-industrialising<br />

countries vary considerably according to<br />

grow ing conditions and market circumstances.<br />

In the Andes, Central Africa and<br />

the Himalayas, potatoes are grown by hand<br />

on small subsistence farms. But in most of<br />

the other regions, cultivation is largely<br />

mechanised.<br />

South America, the continent that<br />

originally gave the world the potato, is now<br />

in fact the region with the smallest potato<br />

2 COURIER 1/08

World potato production 1991-2007<br />

(in million tonnes)<br />

Blue: developed countries<br />

Orange: developing countries<br />

World potato production 1991-2007<br />

Blue: developed countries<br />

Orange: developing countries<br />

200<br />

150<br />

100<br />

nt<br />

50<br />

0<br />

Countries<br />

1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007<br />

million tonnes<br />

❚ Developed 183.13 199.31 177.47 174.63 165.93 166.94 160.97 159.99 155.53<br />

❚ Developing 84.86 101.95 108.50 128.72 135.15 145.92 152.11 160.12 165.13<br />

WORLD 257.25 301.27 285.97 303.36 301.08 312.86 313.09 320.11 320.67<br />

Source: FAOSTAT<br />

harvest (less than 16 million tonnes in<br />

2006 and 2007). Traditionally, potatoes are<br />

grown on small family farms in the Peruvian<br />

Andes. However, potato cultivation<br />

has increased in recent years in Argentina,<br />

Brazil, Columbia and Mexico, where the impetus<br />

for expansion has come from larger<br />

farm-owners, often working together with<br />

breeding organisations.<br />

Fast Food leads the way<br />

in the USA<br />

In 2007, the USA harvested 17.6 million<br />

tonnes, making it the fifth-largest potato<br />

producer in the world. Cultivation is<br />

concentrated in the following states: Idaho,<br />

Washington, Wisconsin, North Dakota and<br />

Colorado. Only a third of all potatoes produced<br />

in the USA is destined for consumption<br />

as fresh produce: around 60% is either<br />

processed into frozen foods such as French<br />

fries, or is made into crisps and starch.<br />

The remaining 6% is retained as seed for<br />

planting.<br />

Canada lies in 12th place on the FAO<br />

list of world producers, with around 5 million<br />

tonnes of production. This reflects a steady<br />

increase since the 1990s that has been driven<br />

by the international export demand for<br />

processed potato products. Thirty-seven<br />

percent of the harvest goes into processing<br />

for export: the biggest customer here is the<br />

USA.<br />

Giants of potato production –<br />

China and India<br />

The combined region of Asia and Oceania<br />

is the world leader in potato production.<br />

The People’s Republic of China produced<br />

72 million tonnes in 2007 (more than<br />

a fifth of the world’s harvest) on around<br />

5 million ha, the world’s largest area under<br />

cultivation (25% of the total). Nevertheless,<br />

potato cultivation is less widespread<br />

in China than maize- and sweet potatogrowing:<br />

the latter crops are used as the<br />

basis for animal feed, whereas the potato is<br />

used mainly for human nutrition (30 kg per<br />

person per year according to FAO figures).<br />

Potato production in India has increased<br />

more than eight-fold within the last<br />

30 years. Today, with its annual harvest of<br />

26 million tonnes, India is the world’s<br />

third-largest producer.<br />

Australia and New Zealand are among<br />

the smaller potato-producing nations, with<br />

a major part of the harvest going into<br />

processing. Impressively high yields are<br />

1/08 COURIER 3

achieved in New Zealand – more than<br />

45 tonnes per ha on average, and up to a<br />

maximum of 70 tonnes. The potato is<br />

among the New Zealanders’ favourite vegetables,<br />

and this is reflected in the figure<br />

for consumption per head – 66 kg a year.<br />

Russia is continental Europe’s<br />

potato king<br />

Until the 20th century, continental Europe<br />

was easily the world’s largest producer of<br />

potatoes. Today, seven European countries<br />

still rank among the world’s ten largest<br />

producers. The leader of the pack is<br />

Russia, with production at 35.7 million<br />

tonnes a year from an area of around 3 million<br />

ha (2006 figure). Second place goes to<br />

the Ukraine, with around 19 million tonnes<br />

from 1.5 million ha. Despite the large<br />

harvests they produce, these two Eastern-<br />

European heavyweights hardly feature at<br />

all as export countries: even today, a large<br />

proportion of the harvest is still lost as the<br />

result of diseases and unsuitable storage<br />

conditions.<br />

With its harvest of 11.6 million tonnes<br />

in 2007, Germany is Europe’s number<br />

three potato producer, and number six in<br />

the world. Despite a 30% decrease in<br />

production and harvested yield over the<br />

last 30 years, Germany remains the largest<br />

Top potato producers<br />

Quantity (tonnes), 2007<br />

1. China 72,000,000<br />

2. Russian Fed. 35,718,000<br />

3. India 26,280,000<br />

4. Ukraine 19,102,300<br />

5. USA 17,653,920<br />

6. Germany 11,604,500<br />

7. Poland 11,221,100<br />

8. Belarus 8,700,000<br />

9. Netherlands 7,200,000<br />

10. France 6,271,000<br />

kg per capita, 2006<br />

1. Belarus 835.6<br />

2. Netherlands 425.1<br />

3. Ukraine 414.8<br />

4. Denmark 291.1<br />

5. Latvia 286.0<br />

6. Poland 271.5<br />

7. Belgium 267.4<br />

8. Lithuania 261.2<br />

9. Russian Fed. 259.0<br />

10. Kyrgyzstan 219.4<br />

producer in Western Europe. The harvest is<br />

used as follows: 6.5 million tonnes become<br />

processed foods and 3.3 million tonnes are<br />

destined for starch production for the domestic<br />

market; a further 3.3 million tonnes<br />

of fresh potatoes and processed products<br />

are exported. Germany is also the numberone<br />

importer of early potatoes for eating –<br />

around 550.000 tonnes (2005 figure),<br />

mainly from France, Italy and Egypt.<br />

The third-largest Eastern European producer<br />

is Poland, with around 11 million<br />

tonnes harvested from around 600,000 ha.<br />

Poland has slipped to 10th place in the<br />

world ranking 2006 as the result of a<br />

decline in production in recent years and<br />

due to adverse weather conditions. But<br />

potatoes are still produced on more than<br />

2 million small-scale farms, representing<br />

about 10% of the agricultural area. Half of<br />

the harvest ends up in animal feed; only a<br />

quarter is used for food production.<br />

Constant level of production<br />

in Holland<br />

The Netherlands has a special place in<br />

European potato cultivation. While the<br />

area of cultivation in Europe as a whole<br />

continues to fall, it remains constant in<br />

Holland. The root crop occupies a quarter of<br />

Dutch agricultural land, and Dutch farmers<br />

achieve record yields of more than 45 tonnes<br />

per ha. Only one half of production is destined<br />

for consumption: 20% is reserved as<br />

seed, and the remaining 30% goes to starch<br />

production. Holland is the world’s premier<br />

producer of certified seed potatoes, with<br />

exports of 700,000 tonnes a year.<br />

France is the leading European exporter<br />

of fresh potatoes (1.5 million tonnes in<br />

2006), especially to Southern Europe.<br />

Some two million tonnes are destined for<br />

the domestic market and one million<br />

tonnes for the processing industry.<br />

With a harvest of around 3.3 million<br />

tonnes, Belgium is among the smaller<br />

European producers, but its farmers are<br />

nevertheless capable of achieving high<br />

yields (around 43 tonnes per ha). More<br />

than 80% of production is processed to<br />

crisps, French fries, starch and other products,<br />

of which more than 1 million tonnes<br />

(2006 figure) are exported.<br />

Diversity of uses<br />

Potatoes are suited to a large variety of<br />

nutritional and technical uses. Less than<br />

50% of the global potato harvest is consumed<br />

in the form of the fresh vegetable.<br />

The largest proportion goes into processing<br />

and refining for food products and food additives.<br />

A significant amount is either used<br />

as the basis for feed for cattle and pigs, or<br />

is processed to starch for industrial use.<br />

Finally, a smaller proportion is retained as<br />

seed potatoes for the following season.<br />

The global trend in terms of consumption<br />

is moving away from the potato as a<br />

basic, staple food, with a shift towards<br />

refined, processed products. The most common<br />

form of processed potatoes is French<br />

fries, as offered in fast food restaurants<br />

around the world. Production is widely<br />

standardized: peeled potatoes are cut into<br />

strips, heated, air-dried, fried, frozen and<br />

finally, packaged. The annual global turn -<br />

over of industrially-prepared French fries is<br />

in the order of more than 11 million tonnes.<br />

Potato flakes and granules are produced<br />

by drying the raw potato down to a water<br />

content of 5 to 8%. These are used as food<br />

additives or in potato products for the convenience<br />

food sector. Further dried potato<br />

products include potato flour and potato<br />

powder. These products are gluten-free,<br />

with a high starch content. Potato flour is<br />

used widely by the food industry as a binding<br />

agent for prepared meals and soups.<br />

Compared with starches from wheat and<br />

maize, potato starch is almost tasteless,<br />

and shows stronger binding properties. Potatoes<br />

are also fermented to allow<br />

the distillation of alcohol, particularly in<br />

Eastern Europe and Scandinavia: vodka<br />

and aquavit are two well-known examples.<br />

Potato starch is also used widely in the<br />

pharmaceutical, textile, wood and paper<br />

industries as a binding agent and to<br />

provide structure.<br />

4 COURIER 1/08

Potato production by region 2007<br />

Potato boom in Asia<br />

In Asian countries (particularly China and<br />

India), the level of potato consumption has<br />

increased many times over within a relatively<br />

short period. This is attributable not<br />

only to population growth, but also to<br />

changing consumer preferences. Citydwellers<br />

in particular see the potato as a<br />

valuable food with a modern, western<br />

touch, so economic growth tends to<br />

increase demand. In contrast, demand for<br />

potatoes in Western Europe and other industrialised<br />

countries has tended to decline<br />

over the years, although the decline appears<br />

to have slowed recently.<br />

Globally speaking, potato consumption<br />

is set to increase further in the future.<br />

It is expected to exceed 400 million tonnes<br />

by the year 2020, an increase of about a<br />

quarter over today’s levels. The European<br />

potato industry should take a careful look<br />

at the potato sector in developing countries<br />

– not only for humanitarian reasons, but<br />

also from an economic point of view.<br />

While the demand for potatoes is stagnating<br />

here in Europe, markets in Asia are expanding<br />

rapidly. Similar trends should also<br />

be expected from Africa und Latin America<br />

in the medium term. International trade<br />

in potatoes and potato products is con -<br />

tinuously on the increase, so a significant<br />

export potential exists for European<br />

industry.<br />

Production quantity<br />

This also applies to breeding. The major<br />

breeding companies are focussing increasingly<br />

on the Asian market. An adage of<br />

potato marketing is that if everybody in<br />

China and Asia were to eat only a single,<br />

small packet of crisps (100 g) once a year,<br />

world potato production wouldn’t be able<br />

to meet the demand. For comparison, the<br />

average annual consumption of crisps in<br />

the USA is 3,000 g, and in Germany<br />

around 1,000 g per person. ■<br />

Harvested area Quantity Yield<br />

hectares tonnes tonnes/hectares<br />

Africa 1,503,145 16,308,530 10.84<br />

Asia/Oceania 8,742,257 137,142,946 15.68<br />

Europe 7,439,553 128,608,372 17.28<br />

Latin America 962,494 15,986,155 16.60<br />

North America 614,972 22,625,958 40.63<br />

WORLD 19,262,421 320,671,961 16.64<br />

Source: FAOSTAT<br />

Mechthilde Becker-Weigel<br />

wirtschaftsdienst agrar

<strong>Bayer</strong> <strong>CropScience</strong><br />

supports China’s<br />

potato development<br />

China is the world’s largest potato-growing<br />

country: with 5 million hectares under<br />

cultivation in 2007, it accounted for<br />

25% of the world’s total production.<br />

Eighty-five percent of China’s growing<br />

area is distributed in the North (single<br />

cropping) and South-West (double<br />

cropping) of the country. The average yield<br />

per hectare is about 16 tonnes. Currently,<br />

most of China’s potato production is used<br />

fresh for eating (60%); processing to potato<br />

chips, French fries and fast-frozen food<br />

only accounts for about 10%.<br />

The development of China’s potato<br />

market has been hampered by a lack of<br />

access to various technologies: only 25%<br />

of planted seed potatoes are certified<br />

virus-free, and only 1% of farmers use<br />

machinery in potato production. In addition,<br />

most farmers lack knowledge of pest<br />

and disease control methodology.<br />

But things are changing. As the 5th<br />

largest crop in China, the potato is gaining<br />

in importance. The yield per unit area of<br />

rice, corn and wheat is not expected to increase<br />

due to technology limitations. The<br />

potato can yield three to four times as much<br />

as these crops per hectare – and it is also<br />

more drought-resistant than rice and wheat.<br />

As 60% of China’s arable land is dry, potato<br />

growing is regarded by the government as<br />

one of the best ways of meeting the<br />

increasing food demand of 1.3 billion<br />

people, as well as a good opportunity for<br />

farmers to improve their income. With<br />

strong support from the government, the<br />

potato-planting area is expected to increase<br />

further to 6.6 million hectares; the use of<br />

Trucks loaded with<br />

potatoes at a<br />

purchasing station in<br />

Xiji county, North-West<br />

China.<br />

6 COURIER 1/08

virus-free seed potatoes will also be encouraged.<br />

In terms of usage, processing into<br />

potato chips, French fries and fast-frozen<br />

food will have increased strongly by 2010.<br />

Modern solutions<br />

<strong>Bayer</strong> <strong>CropScience</strong> first entered the potato<br />

market in China in 2007. The company<br />

is able to provide a product portfolio<br />

(Gaucho ® for seed treatment, Antracol ®<br />

for Alternaria control and Infinito ® for<br />

Phytophthora control) that is well-suited<br />

to China’s potato production conditions.<br />

<strong>Bayer</strong> <strong>CropScience</strong> is actively cooperating<br />

with the relevant government organizations<br />

towards the introduction of state-ofthe-art<br />

crop protection solutions. In 2007,<br />

large scale demonstrations of Infinito and<br />

Antracol were organised in several key<br />

provinces. In addition, many field seminars<br />

were held, during which <strong>Bayer</strong> <strong>CropScience</strong><br />

sales personnel trained farmers how to<br />

grow healthy potatoes and demonstrated<br />

the efficacy of <strong>Bayer</strong> <strong>CropScience</strong> product<br />

solutions. “We intend to offer advanced<br />

technical solutions to potato growers and<br />

to help them to increase yield and improve<br />

quality, so that they can meet customers’<br />

demand for healthy potatoes,” says Eric<br />

Tesson, Head of Business Development at<br />

<strong>Bayer</strong> <strong>CropScience</strong> in China.<br />

With the rapid development of China’s<br />

potato market, some big international food<br />

companies have begun actively operating<br />

in China, with some success. They have<br />

their own potato supply chains as well as<br />

their own potato farms, where high-quality<br />

potatoes can be produced using modern<br />

farm management and pest and disease<br />

control technologies. <strong>Bayer</strong> <strong>CropScience</strong><br />

has established good business relationships<br />

with these companies and is providing<br />

the necessary support by offering training<br />

and sharing knowledge of good practice<br />

in potato farming and management<br />

gained abroad. <strong>Bayer</strong> <strong>CropScience</strong> is sharing<br />

its wide-ranging expertise in plant<br />

health to enable growers to produce highquality<br />

potatoes.<br />

<strong>Bayer</strong> <strong>CropScience</strong> is already an active<br />

player in China’s potato market. We will<br />

continue to do our best to support the<br />

development of China’s potato industry<br />

by providing a comprehensive, practical<br />

package of technologies – to ensure that<br />

Chinese consumers enjoy high-quality,<br />

healthy potatoes. ■<br />

1/08 COURIER 7

The potato –<br />

In many parts of the world, the potato is becoming an<br />

increasingly popular source of nutrition. It contains a number<br />

of valuable components. We interviewed a potato expert:<br />

Sabine Sulzer, Product Manager for plant-derived products at<br />

the CMA (Central Marketing Organisation of German<br />

Agricultural Indu stries).<br />

8 COURIER 1/08

Sabine Sulzer, Product<br />

Manager for plant-derived<br />

products at the CMA (Central<br />

Marketing Organisation of<br />

German Agri cultural Industries)<br />

Sulzer: In industrial countries, the trend is<br />

in the opposite direction. Europe is still<br />

second only to Asia in terms of global<br />

production, but cultivation there has been<br />

declining continuously for some years now.<br />

The Europeans, with their consumption<br />

per person of 96 kg, are still the potatolovers<br />

par excellence. Nevertheless, conversatile<br />

and nutritious<br />

Courier: Mrs Sulzer, the United Nations<br />

have declared 2008 the International<br />

Year of the Potato – why<br />

Sulzer: Against a background of growing<br />

global problems, such as hunger, poverty<br />

and environmental degradation, the potato<br />

is becoming an increasingly important<br />

source of nutrition for the world’s population.<br />

That’s why the General Assembly of<br />

the United Nations have declared 2008 the<br />

International Year of the Potato.<br />

Courier: How important is the potato<br />

Sulzer: The potato is the world’s fourthmost<br />

important staple food after rice,<br />

wheat and maize. In 2006, 314 mio. tonnes<br />

of potatoes were harvested globally.<br />

Indeed, the potato is the only staple food<br />

that has seen an increase in the area cultivated<br />

around the world in recent years.<br />

Developing countries in particular have<br />

shown a continuous increase in cultivation;<br />

in 2005, for the first time, more potatoes<br />

were harvested in these countries than in<br />

industrial countries. The “spud” is well on<br />

its way to becoming one of our most im-<br />

portant sources of nutrition. It alleviates<br />

hunger and poverty, particularly in rural<br />

areas.<br />

Courier: And how is the situation<br />

looking in industrial countries<br />

1/08 COURIER 9

Potatoes contribute important nutrients, vitamins and minerals to the daily menu. As well as being rich in valuable nutrients,<br />

they can also be prepared and cooked in a variety of ways. Photos: CMA, Germany<br />

sumption is on the wane. Germany is the<br />

European Union’s biggest producer of<br />

potatoes and is ranked number six in<br />

terms of global production. But consumption<br />

per person here (66 kg) lies below the<br />

European average. The most prominent<br />

change has been the consumers’ move<br />

away from fresh potatoes towards<br />

processed potato products. Indeed, this<br />

applies to all industrial nations.<br />

Courier: What makes the potato so<br />

suitable for human consumption<br />

Sulzer: Potatoes have a broad spectrum of<br />

valuable contents and they are among the<br />

foods with the highest nutrient density,<br />

which is a measure of the balance between<br />

the nutrients a food contains and its energy<br />

content. Here, the potato does especially<br />

well. It has a calorie content of only 70<br />

kilocalories per 100 grammes of cooked<br />

potato, but at the same time it contributes a<br />

major part of our need for biologicallyuseful<br />

proteins, carbohydrates, vitamins<br />

and minerals.<br />

Courier: So the potato isn’t simply<br />

the “fattener“, as its reputation would<br />

have it<br />

Sulzer: No, certainly not. This myth<br />

derives from the potato’s capacity to make<br />

one feel sated. The low calorie content is<br />

an inverse result of the high water content<br />

(80%). Moreover, the potato contains hardly<br />

any fat. The energy content is comparable<br />

with, or even slightly lower than, that<br />

of cooked rice (84 kilocalories) and pasta<br />

(94 kilocalories per 100 g). This disproves<br />

the myth that the potato is a fattening food.<br />

Courier: Why is the potato’s protein<br />

content always emphasized At 2% of<br />

fresh material, it doesn’t seem especially<br />

high.<br />

Sulzer: The potato’s high water content<br />

means that its protein content is – relatively<br />

speaking – low. Nevertheless, the protein<br />

it does contain is highly valuable –<br />

with a favourable composition in terms of<br />

essential amino acids. The essential amino<br />

acid lysine, in particular, is present in high<br />

quantities. For these reasons, potato proteins<br />

are among the most beneficial of all<br />

the proteins available from plant-derived<br />

products, and they complement those contained<br />

in animal-derived foods when<br />

served together. For example, the combination<br />

of potato and egg provides a very<br />

favourable spectrum of proteins.<br />

Courier: What’s the main constituent<br />

of a potato besides water<br />

Sulzer: At 16g per 100g, the carbohydrates<br />

(mainly in the form of starch) are the<br />

second-most prominent group of constituents<br />

in the potato; they also deliver the<br />

most energy. In fact, raw potato starch is<br />

practically indigestible for people; it only<br />

becomes so after simmering in water at a<br />

temperature around the boiling point. This<br />

is why you shouldn’t eat potatoes raw. The<br />

fact that the starch gradually breaks down<br />

into glucose (a building block of sugars)<br />

during digestion is very positive in terms<br />

of nutritional physiology. Roughage, in the<br />

form of indigestible carbohydrates, is present<br />

at up to 2 % in the potato; it contributes<br />

to the feeling of satedness and helps to<br />

ensure regular intestinal movement.<br />

Courier: And what about vitamins<br />

and minerals<br />

Sulzer: When it comes to vitamins, it’s the<br />

high vitamin C content that should be<br />

emphasised: this is why the potato is sometimes<br />

also called the “lemon of the North“.<br />

For example, a young, cooked potato<br />

10 COURIER 1/08

Some tips for<br />

preparing potatoes<br />

• Cooking in a little water with the<br />

skin left on is the best way of<br />

preserving the nutritional value of<br />

potatoes during preparation.<br />

• In order to avoid loss of vitamins,<br />

boiled potatoes shouldn’t be kept<br />

warm for too long.<br />

• Potatoes should always be stored<br />

in the dark, under cool, dry<br />

conditions (although not in the<br />

refrigerator). The optimal storage<br />

temperature for potatoes is<br />

about 4°C.<br />

with its skin contains 15 mg vitamin C per<br />

100 g, which is slightly more than an apple<br />

does (10 mg). A 200 g portion of potato<br />

covers 28% of an adult’s daily vitamin C<br />

requirement. But this high content can<br />

decrease considerably during long storage,<br />

or if the potatoes are prepared and cooked<br />

in the wrong way. Potatoes are also a good<br />

source of the water-soluble B-vitamins and<br />

niacin. Regarding minerals, potatoes have<br />

a high potassium content, and at the same<br />

time, a low sodium content. This is why the<br />

potato is often recommended in special<br />

diets. Ten percent of the recommended<br />

daily intake of magnesium can be covered<br />

by a 200 g portion of potato. Phosphorus<br />

and iron are also present in significant concentrations.<br />

Incidentally, the high vitamin<br />

C-content encourages the uptake of iron<br />

into the blood.<br />

Courier: Nutritional science has been<br />

focussing a lot on secondary plant<br />

substances recently. Do potatoes<br />

contain secondary plant substances<br />

Sulzer: Secondary plant substances arise<br />

as the result of the plant’s metabolism. This<br />

group is thought to comprise 60-100,000<br />

chemically-different substances. They serve<br />

the plant in many ways: for colouration; in<br />

defence against pests and diseases; and as<br />

aromas. For people, they can have a variety<br />

of health-promoting effects: for example<br />

by stimulating the immune system and<br />

defence against infection, and by preventing<br />

the oxidation of other substances. Potatoes<br />

contain their share of secondary substances:<br />

mainly carotenoids, polyphenols,<br />

protease-inhibitors, phytic acids und<br />

anthocyanins. But depending on how the<br />

potatoes are prepared, some secondary<br />

substances can be inactivated. For example,<br />

simmering causes protease-inhibitors<br />

to lose their activity entirely.<br />

Courier: Has this new knowledge of the<br />

potato’s nutritional value led to a change<br />

of perception among consumers<br />

Sulzer: In 2005, we conducted a market<br />

survey of consumers to investigate the<br />

potato’s image. A total of more than 1,000<br />

heads of households throughout Germany<br />

aged 18 or older were questioned in personal<br />

interviews. The study showed that<br />

the potato is still today a valued part of our<br />

diet. Around two-thirds of households<br />

cook fresh potatoes several times a week.<br />

The versatile spud, which enjoys a high<br />

level of popularity here in Germany, is<br />

predominantly seen as a well-proven, traditional<br />

and important basic food. But a<br />

change of image is under way between the<br />

generations: older consumers are more<br />

likely to consider the potato to be a modern,<br />

up-to-date product than the younger<br />

consumer. Indeed, the potato is losing its<br />

relevance in the diets of younger households.<br />

Courier: How do you see the potato’s<br />

future in terms of consumer behaviour<br />

Sulzer: People’s interest in being able to<br />

prepare dishes quickly and easily will be<br />

the main driver in the continuing move<br />

towards processed potato products. The<br />

potato will also score points in future<br />

because of the numerous ways of preparing<br />

it. There’s a potato dish available for every<br />

taste: chips, mashed potato, dumplings,<br />

fried potato, gnocchi etc. There’s no limit<br />

to how potatoes can be prepared.<br />

Courier: Mrs Sulzer, let’s end<br />

with a personal question: what’s your<br />

favourite potato dish<br />

Sulzer: Coming as I do from Bavaria, my<br />

favourite dish since childhood has been<br />

potato dumplings with lots of sauce. But<br />

preparing the dumplings from scratch is<br />

too much work for me, so I tend to go for<br />

the ready-mixed dumplings from the cold<br />

compartment. ■<br />

1/08 COURIER 11

The UK Potato Project –<br />

Participation that paid off<br />

The whole is greater than the sum of its<br />

parts, they say. It certainly applies to Food<br />

Chain Partnership. Because, if all members<br />

of the chain – from field to fork – become<br />

partners who understand each others<br />

needs and requirements, everyone gains.<br />

<strong>Bayer</strong> <strong>CropScience</strong> therefore encourages<br />

and facilitates Food Chain Partnerships all<br />

over the world, contributing the company’s<br />

own expertise and extensive knowledge.<br />

One such partnership was the UK Potato<br />

Project introduced here.<br />

As customers increasingly become<br />

aware of what they eat, their expectations<br />

are on the rise. After a number of food<br />

scares, such as the BSE crisis, legislation<br />

within the EU has put more emphasis on<br />

consumer and retailer expectations in terms<br />

of high-quality and safe produce.<br />

In this context, the market in the United<br />

Kingdom is particularly advanced with a<br />

strong involvement of retailers and processors<br />

in food production. Against this background<br />

<strong>Bayer</strong> <strong>CropScience</strong> was to launch<br />

Infinito ® , a new product against potato late<br />

blight.<br />

While the general aim for all members<br />

of the potato food chain should be highquality,<br />

healthy-looking potatoes, individual<br />

members have different requirements<br />

and demands on a new crop protection prod -<br />

uct. To farmers, high effectiveness against<br />

Phytophtora as well as operator and environmental<br />

safety is paramount. But flexible<br />

dose rates and spraying intervals are<br />

also important. Next in the line, potato<br />

processors are confronted with a) consu -<br />

mers’ quality expectations and b) technical<br />

demands such as the shape and size of<br />

potatoes and their frying qualities to guarantee<br />

successful processing at a reasonable<br />

price. Retailers finally, especially those in<br />

the fresh potato segment, have to cope with<br />

consumers’ sensibility towards looks and<br />

cooking properties of fresh food. To them,<br />

healthy and clean potato skin is of great<br />

importance. In order to best meet the different<br />

expectations of those involved, <strong>Bayer</strong><br />

<strong>CropScience</strong> decided to invite all members<br />

of the potato value chain to field trials<br />

and cooperate with them in the final development<br />

of Infinito.<br />

Sabine Stolz, Food Chain Manager<br />

Europe and Global Key Relation Manager<br />

for UK supermarket retailers at the <strong>Bayer</strong><br />

<strong>CropScience</strong> Headquarters in Monheim,<br />

points out: “There are two strategies in<br />

Food Chain Partnerships we pursue at <strong>Bayer</strong><br />

<strong>CropScience</strong>. Usually the emphasis lies on<br />

individual crop cultures where, for a particular<br />

location or situation, we help define<br />

a schedule of crop protection measures to<br />

be taken over the course of the year. Of<br />

course, only registered, approved<br />

crop protection products can be<br />

included in this schedule.<br />

The UK Potato<br />

Project was something<br />

new for us.<br />

Here, the potato value chain members were<br />

involved at the developmental stage of a<br />

new crop protection product already.”<br />

Patrick Mitton, Cambridge-based food<br />

industry stewardship manager, says: “At<br />

<strong>Bayer</strong> <strong>CropScience</strong>, we naturally want to<br />

introduce products that are tailored to the<br />

demands of the market. It is essential to develop<br />

products that satisfy our customers’<br />

expectations and offer the best possible solution<br />

for all interested parties.”<br />

To begin with, the new product’s active<br />

substance, fluopicolide, had a favourable<br />

technical profile. Not only does it offer<br />

outstanding efficacy, particularly in respect<br />

of tuber blight control. It also met the expectations<br />

of the food companies. But<br />

there is always room to improve things. So,<br />

two seasons before the launch of Infinito,<br />

many British farmers, processors and retailers<br />

were asked for their ideas and recommendations<br />

for a product profile. During<br />

the two year pre-launch development<br />

The potato farmer’s aim:<br />

high-quality and<br />

healthy-looking potatoes.<br />

12 COURIER 1/08

phase, representatives from<br />

across the complete potato supply<br />

chain were invited to visit<br />

the field trials.<br />

“Together we evaluated the<br />

dose rates and spraying intervals<br />

to be considered”, Patrick Mitton explains.<br />

“Potato chain members thus had the<br />

chance to contribute to the final design of<br />

the new product, knowing their participation<br />

was going to pay off and be of advantage to<br />

them.”<br />

In the end, the technical profile of Infinito<br />

was so finely tuned to the expectations<br />

of a crop protection product by the<br />

UK food supply chain, that if they had<br />

been asked to design a product to satisfy<br />

their needs, Infinito would have been the<br />

result. Food businesses in the UK were<br />

keen to support the product from the first<br />

day of commercial launch. This isn’t the<br />

norm, as Sabine Stolz reveals: “Usually, a<br />

new crop protection product is developed<br />

Patrick Mitton, Food Industry Manager for <strong>Bayer</strong><br />

<strong>CropScience</strong> in the United Kingdom.<br />

and launched without involvement of food<br />

chain members. The big retailers then wait<br />

and see until they have gathered enough information<br />

about the benefits of the product.<br />

This takes about a year or two on average.<br />

Only then do they give their approval and<br />

include the new crop protection product on<br />

their lists.”<br />

Not with Infinito. Due to the UK Potato<br />

Project, confidence was so high right from<br />

the start that the new product was placed<br />

on all recommendation protocol lists, thus<br />

ensuring a commercial “free passage” in<br />

time for the growing season. So much was<br />

the enthusiasm, that players from across<br />

the complete food supply chain requested<br />

Sabine Stolz, Food Chain Manager Europe, at <strong>Bayer</strong><br />

<strong>CropScience</strong> Headquarters in Monheim, Germany<br />

the use by brand. Sabine Stolz smiles:<br />

“Everyone knows Infinito, everybody wants<br />

to use it.” Patrick Mitton adds: “We feel a<br />

great sense of achievement when we hear<br />

the great retailers request <strong>Bayer</strong> Crop-<br />

Science products by name.”<br />

Moreover, the UK Potato Project has<br />

increased trust, flexibility and a great relationship<br />

among all parties involved. “It<br />

was a decidedly positive experience”,<br />

Sabine Stolz recalls. “We did not expect<br />

such a great response. Now we have adopted<br />

the same strategy for a product that will<br />

be launched in two years time on a different<br />

market. From the UK Potato Project<br />

we’ve learned just how important and<br />

meaningful it is to involve all food chain<br />

partners at a very early stage already –<br />

especially in the development<br />

of a new product.” ■<br />

1/08 COURIER 13

Agrico and HZPC on the future of<br />

Dutch potato cultivation:<br />

‘Innovation<br />

and knowledge<br />

determine<br />

our success’<br />

Just as for other agricultural<br />

crops, seed potato<br />

cultivation will also be<br />

dominated by scaling up<br />

in the coming years.<br />

Experts in the sector<br />

anticipate that in ten<br />

years’ time, only about<br />

2,000 of the present<br />

3,000 seed-potato<br />

growers will remain. It is<br />

expected, however, that<br />

the present cultivated<br />

area of 36,000 hectares<br />

will remain stable.<br />

14 COURIER 1/08

For more than a century, the Netherlands<br />

has been a leader in seed potato production.<br />

With an area of approx. 36,000<br />

hectares, it accounts for about 40 percent<br />

of the total Western European acreage. The<br />

Netherlands is the leader in the fields of<br />

new varieties and export, and has made a<br />

name for itself in terms of cultivation<br />

knowledge and modernization. But will<br />

this remain the case Competition from other<br />

countries has increased in recent years,<br />

with France, Germany and Scotland in the<br />

lead. How are Dutch commercial companies<br />

dealing with this And how do they<br />

plan to remain leaders in the world of seed<br />

potatoes The two largest commercial<br />

companies, HZPC and Agrico, give their<br />

vision of the future in five main areas<br />

(competition, varieties, licenses, diseases<br />

and knowledge).<br />

Competition<br />

“Yes, it is true - the Netherlands is losing<br />

something of its lead.” Gerard Backx, General<br />

Director of the commercial seed potato<br />

company HZPC does not beat about the<br />

bush. He sees other countries, with France<br />

furthest ahead, slowly stealing a share of<br />

the market from the Netherlands. “But you<br />

have to consider this in proportion,” he<br />

emphasizes. “Each year the Netherlands<br />

exports about 700,000 tonnes of seed potatoes.<br />

Our most important competitors<br />

France, Scotland and Germany together<br />

export about 230,000 tonnes. I anticipate<br />

that in the coming years, the relationship<br />

will shift at the very most by a few thousand<br />

tonnes. So we are therefore talking<br />

about an approximate one percent change.”<br />

One area in which the Netherlands is miles ahead<br />

of other countries at the moment is the breeding<br />

of (successful) new varieties. Both Agrico and<br />

HZPC are making an important contribution to this<br />

through their own breeding operations (Agrico<br />

Research and HZPC Metslawier).<br />

However, Backx is not saying that the<br />

Netherlands has nothing to fear. “As a<br />

leading seed potato-producing country,<br />

we shall have to keep up in terms of knowledge,<br />

quality and modernization. Other<br />

countries are busily catching up on all<br />

three points. We must therefore do everything<br />

we can to maintain our lead.”<br />

France in particular is doing well<br />

Jan Van Hoogen, Commercial Director at<br />

the commercial potato company Agrico,<br />

confirms these efforts to overtake the<br />

Netherlands. In his view, France in particular<br />

has made great progress. “With regard<br />

to cultivation knowledge, mechanization<br />

and storage technology, the French are no<br />

longer behind the Netherlands. They can<br />

grow potatoes just as well as we can.”<br />

Van Hoogen emphasizes that the emergence<br />

of other countries is not disadvantageous<br />

for the Netherlands per se. “All large<br />

Dutch commercial companies have subsidiaries<br />

or establishments in France,<br />

Germany and Scotland. And in recent<br />

years, they have all grown considerably.<br />

As a result, the market share of Dutch<br />

varieties has also increased greatly. A large<br />

part of the money that we earn from this<br />

returns to benefit Dutch growers.”<br />

Varieties<br />

One point in which the Netherlands remains<br />

miles ahead of other countries is the<br />

breeding of (successful) new varieties.<br />

Both Agrico and HZPC are playing an important<br />

role here with their own breeding<br />

operations (Agrico Research and HZPC<br />

Metslawier). The two commercial companies<br />

each deal in about 100 different potato<br />

varieties, the majority of which they<br />

have bred themselves.<br />

HZPC director Backx says that about<br />

70 of the 100 varieties are being actively<br />

produced and marketed. The others are<br />

either in the introductory or run-down<br />

phases. HZPC aims to get three new cultivars<br />

onto the European List of Varieties<br />

each year. Of these, at least one must<br />

become a commercial success, which<br />

requires that after an introductory period<br />

of three to five years, at least 100 hectares<br />

must be cultivated, with total production of<br />

at least 3000 tonnes. If the variety does not<br />

reach this threshold, it will be withdrawn<br />

from the market as quickly as possible.<br />

“The reality is that many varieties remain<br />

on the borderline. You have to clear these<br />

out so that the successful varieties get<br />

more space on the plots,” is how Backx<br />

describes the strategy. In practice, this<br />

sometimes meets with resistance – but this<br />

is part of the trade, he says. “In the case of<br />

the potato, there is an enormous hodgepodge<br />

of wishes from around the world.<br />

We try to meet these as much as we can –<br />

but not at any price. Sometimes varieties<br />

do well in small niches. But the niches<br />

must ultimately contribute to the orga -<br />

nization’s results. If that fails, we get our<br />

fingers burnt. A variety must be profitable.”<br />

Well-known varieties have a lot of power<br />

According to Backx, the success of a variety<br />

depends on many factors. Obviously<br />

the properties of the variety play a very important<br />

role, but the ‘pulling power’ of the<br />

known major varieties must not be underestimated.<br />

For HZPC, these are above all<br />

the varieties Spunta and Desirée – both<br />

breeds from the ‘forebears’ of the company,<br />

Hettema and De ZPC. Backx: “In important<br />

export markets such as North<br />

Africa, Spunta in particular has a cast-iron<br />

image. The variety stands for confidence,<br />

quality and reliability. For growers in this<br />

region, a new variety should preferably<br />

have the shape and qualities of a Spunta.<br />

And of course the variety must be demonstrably<br />

better.” HZPC does indeed have an<br />

‘improved Spunta’, Backx says. “Only it<br />

takes a great deal of time and effort to<br />

convince our customers of this.”<br />

‘Breed what the customer wants’<br />

According to Agrico Commercial Director<br />

Van Hoogen, the secret of a successful<br />

breed always lies in the wishes of the<br />

customer or consumer. “The art is therefore<br />

to remain in discussion with all parties<br />

in the chain, so that you can provide them<br />

as far as possible with varieties that<br />

possess the desired qualities.” As an example,<br />

he gives the desire of the French fries<br />

industry to be able to use the same variety<br />

all year round, in order not to have to make<br />

any changes in the factory, and to be able<br />

to supply a constant quality to the end-user.<br />

“For us, that means a continuous search for<br />

varieties that produce a high yield early in<br />

the season, and allow storage until the new<br />

season without loss of quality. The closer<br />

we come to that, the more rapidly new<br />

varieties are accepted.”<br />

Licenses<br />

The use of new, licensed varieties is also<br />

vital for both companies in order to regain<br />

the investment made for all the breeding<br />

efforts. After approval on the Variety List,<br />

1/08 COURIER 15

This is HZPC<br />

HZPC Holland B.V. came into being in 1999 through the merging of two large seed<br />

potato export companies in the Netherlands: Hettema and De ZPC, each with more<br />

than 100 years of experience behind them. The HZPC headquarters are located in<br />

Joure (Friesland, Netherlands).<br />

The core activities of HZPC are breeding, growing and selling seed potatoes.<br />

HZPC is one of the world’s largest commercial enterprises in seed potatoes.<br />

Approximately 620 seed potato growers - with a total acreage of almost 12,000<br />

hectares - are affiliated to HZPC Holland. In recent years, total production has<br />

varied from 330,000 to 400,000 tonnes of seed potatoes. Eighty to 90 percent of<br />

this volume is destined for export. HZPC thus accounts for more than 40 percent<br />

of the total Dutch seed potato export volume.<br />

HZPC exports seed potatoes to 80 different countries. The company has subsidiaries<br />

in Portugal, Spain, France, Poland, the United Kingdom, Canada, Argentina,<br />

Russia and Scandinavia.<br />

To support its core activity (seed potatoes), HZPC also deals in ware potatoes.<br />

In this way HZPC’s protected potatoes are promoted within the supermarkets.<br />

Gerard Backx, General Director of HZPC<br />

Holland B.V.: “As a leading seed potatoproducing<br />

country, we shall have to keep<br />

up in terms of knowledge, quality and<br />

modernization.”<br />

farmers are growing it themselves. As a<br />

result, the concept of license payments has<br />

got lost to some extent. In order to chart<br />

the seed potato routes – and thus the<br />

license obligations – HZPC recently<br />

opened an office in Argentina. For a number<br />

of other countries, a license fee is<br />

demanded when the seed potatoes are<br />

purchased: the customer is then free to<br />

grow the variety once or twice.<br />

Of all the seed potatoes that HZPC and Agrico sell, 75 to 85 percent is destined for export. About half are<br />

transported to their destination by ship.<br />

a breeder’s rights (license) to a variety<br />

remain valid for 30 years. “We therefore<br />

have to make the maximum profit from a<br />

variety during that period,” is how HZPC<br />

Director Backx summarizes an important<br />

aim of the company. Varieties such as<br />

Spunta and Desirée – which can be grown<br />

freely because the license period has<br />

expired – have thus gained two faces. “On<br />

the one hand, they are an excellent way of<br />

displaying our achievements of the past;<br />

but on the other hand, they no longer bring<br />

in any license payments, and they sometimes<br />

inhibit the breakthrough of new<br />

varieties,” is how Backx describes the<br />

sometimes tricky situation.<br />

Payment is not always a matter of course<br />

In addition to the dilemma of the older varieties<br />

that sometimes sit in the way, the<br />

payment of the license fees is sometimes<br />

an awkward point. Of the 80 countries to<br />

which they export, there is ‘a handful’<br />

that do not take licenses very seriously,<br />

according to Backx. In one particular case,<br />

it is unwillingness; but more often it is a<br />

question of inadequate administration or<br />

organization. As an example, Backx mentions<br />

Argentina, where the French fries<br />

variety Innovator has made a considerable<br />

breakthrough in recent years. Initially, the<br />

variety was only grown by the industry.<br />

But now that the variety has proven itself,<br />

Licenses vital in order to pay for<br />

breeding work<br />

According to Agrico Director Van Hoogen,<br />

it is not only distant countries that cause<br />

problems with license payments. Cases are<br />

also sometimes brought against growers in<br />

Belgium, France, Germany and the United<br />

Kingdom who do not take licenses seriously.<br />

An awkward point here is that although<br />

these countries respect the license legislation,<br />

a lot of negotiations are still ongoing<br />

about the precise method of payment. “As<br />

a result, Agrico misses out on many millions<br />

of Euros per year. And we need that<br />

money to offset the breeding costs.”<br />

Diseases<br />

In the area of diseases and infestations, the<br />

prevention and/or control of the Erwinia<br />

bacterium (cause of black leg and stalk<br />

rot) will continue to be a major challenge.<br />

Despite the numerous efforts that have<br />

been made in research and cultivation in<br />

recent years, the problem is still increasing.<br />

Van Hoogen anticipates that the<br />

Netherlands is not yet free of the bacterial<br />

problem. “You can’t do anything to combat<br />

16 COURIER 1/08

This is Agrico<br />

Agrico is a co-operative organization of approximately 1000 potato growers.<br />

Together, they produce about 600,000 tonnes of seed potatoes and ware<br />

potatoes each year that are marketed by Agrico itself.<br />

Agrico has a large number of subsidiaries, including its own packing company for<br />

ware potatoes, its own breeding and research operation, and many test fields in<br />

the Netherlands and abroad. All activities are managed from the Head Office in<br />

Emmeloord (Fl.).<br />

Agrico has its own sales offices in France, Italy, the United Kingdom, Hungary, the<br />

Czech Republic and Canada. In addition, it has representatives in almost all seed<br />

potato-importing countries. Agrico exports seed potatoes to more than 80 different<br />

countries.<br />

Jan van Hoogen, Commercial Director of<br />

Agrico: “The art is therefore to remain in discussion<br />

with all parties in the chain, so that<br />

you can provide them as well as possible with<br />

varieties that possess the desired qualities”.<br />

With an area of approx. 36,000 hectares under cultivation, the Netherlands accounts for about 40 percent of<br />

the total Western European seed potato acreage.<br />

it with breeding work, because there are no<br />

resistances to bacterial disease. And as far<br />

as cultivation measures are concerned, we<br />

still know too little to enable us to tackle<br />

the problem effectively.” In addition, he<br />

anticipates that the increasingly capricious<br />

weather will exacerbate the problem of<br />

bacterial diseases.<br />

Erwinia bacteria being tackled<br />

on many fronts<br />

Backx is somewhat less sombre about the<br />

bacterial threat. Although he does not wish<br />

to trivialize the problem, he says that competitor<br />

countries such as France, Scotland<br />

and Germany are experiencing it to exactly<br />

the same extent. “It is therefore not just<br />

a problem for the Netherlands but for all<br />

seed potato-producing countries.” Backx<br />

anticipates that definite solutions will<br />

come, even though they are not actually in<br />

view at the present time. “I remember well<br />

the problems with brown rot and ring rot a<br />

few years ago. We thought that we would<br />

never get them under control either. But<br />

neither of them has been found in recent<br />

years. I therefore anticipate that in time we<br />

shall be able to overcome bacterial disease,<br />

too.” According to the HZPC Director,<br />

first research results indicate that agricultural<br />

hygiene and contamination (via harvesting<br />

machines) play an important role<br />

in the spread of Erwinia. “Growers therefore<br />

have an opportunity to tackle the<br />

problem.” He also states that the Dutch<br />

general inspection service for agricultural<br />

seeds and seed potatoes (NAK) is at present<br />

advising on changes in the inspection<br />

system to counter bacterial disease. “We are<br />

thus tackling the problem on many fronts.<br />

Sooner or later that must lead to success.”<br />

Knowledge<br />

In order to remain leaders in the cultivation<br />

of seed potatoes, knowledge is the main<br />

thing you need. The two company directors<br />

readily agree on this. Backx says that in<br />

recent years, there has been a strict selection<br />

of seed potato growers by HZPC. He<br />

estimates that, as a result, the number of<br />

growers engaged has fallen by approximately<br />

40 percent since 2000. The company<br />

has looked not only at the farm’s technical<br />

conditions for being able to grow<br />

good seed potatoes (such as good soil and<br />

the availability of fresh water), but also at<br />

the grower’s knowledge and management<br />

qualities. “I can state that knowledge and<br />

good management determine more than<br />

seventy percent of the success. Anyone<br />

who wants to survive in seed potato cultivation<br />

in the future must have these.”<br />

Backx emphasizes that success does not<br />

depend on acreage per se. “We have many<br />

growers in our pool who have 30 to 40<br />

hectares and who do excellently – both<br />

technically and financially. This is because<br />

they are experts and have their operation<br />

well under control. But if they want to increase<br />

to 80 or 90 hectares of crop, they<br />

must delegate work and have management<br />

qualities. And that is often a difficult point.<br />

Not everybody has the skill to delegate<br />

responsibilities. And that has to be done,<br />

because it is impossible to oversee such a<br />

large acreage alone.”<br />

‘Large growers know how to apply their<br />

knowledge’<br />

According to Agrico Director Van Hoogen,<br />

scaling-up in seed potato cultivation is<br />

inevitable, just as in other crops. He anticipates<br />

that in ten years’ time, only about<br />

400 of the current 600 Agrico growers will<br />

remain, with approximately the same<br />

acreage (12,000 hectares). In contrast to<br />

his colleague Backx, he is not worried<br />

about the management qualities of the<br />

survivors. “The larger growers know perfectly<br />

well how to accumulate and apply<br />

their knowledge. And with the ever higher<br />

level of education of the younger guard,<br />

I expect that this situation will continue to<br />

get better.” ■<br />

Written by: Han Hammink<br />

1/08 COURIER 17

Phytophthora<br />

infestans<br />

is becoming increasingly<br />

aggressive<br />

The fungal pathogen Phytophthora infestans is increasing its hold<br />

on potato crops in Europe. In recent years, a wide range of new<br />

pathotypes has emerged through generative (sexual) reproduction,<br />

allowing the disease to become more aggressive and more<br />

damaging. This is clear from data collected by Euroblight, the<br />

European knowledge network for Phytophthora infestans. Potato<br />

researcher and Phytophthora specialist Dr. Ir. Huub Schepers of the<br />

PPO Research Centre in Lelystad (NL) outlines the development of<br />

the disease and indicates how it can be controlled.<br />

At the beginning of the 1970s, only one<br />

mating type (A1) of Phytophthora infestans<br />

was present in Europe. This meant<br />

that the pathogen could only reproduce<br />

asexually (vegetatively) at that time. The<br />

life-cycle was therefore quite stable and<br />

predictable, so it was relatively easy to<br />

control the disease effectively. This situation<br />

changed when, halfway through the<br />

1970s, a second mating type (A2)<br />

entered Europe from Mexico, allowing the<br />

fungus to start reproducing sexually (A1 x<br />

A2) as well. Initially, type A2 was found<br />

locally, mainly in the Netherlands and<br />

Scandinavia: but by now, in 2008, both<br />

18 COURIER 1/08

“Phytophthora<br />

infestans will<br />

continue to adapt<br />

more rapidly in the<br />

coming years. We<br />

must therefore<br />

outsmart the<br />

pathogen and<br />

attack it in all<br />

possible ways.”<br />

Huub Schepers<br />

mating types are endemic throughout<br />

Europe.<br />

Oospores (which develop via sexual<br />

reproduction) are now found in virtually<br />

all Western and Northern European countries.<br />

In the Netherlands, 60 to 70 % of all<br />

potato-growing areas have mixed populations<br />

of A1 and A2, according to long-term<br />

surveys by the PPO Research Centre. Early<br />

infection caused by oospores occurs mainly<br />

in lighter soils and areas with very short<br />

rotations. This applies particularly to the<br />

North-East of the Netherlands, where<br />

starch potato cultivation is concentrated.<br />

In the period 1999 – 2005, about 32 percent<br />

of all early infections in that region<br />

appeared to be caused by oospores.<br />

Oospores are a considerable<br />

threat<br />

Sexual reproduction via oospores is a serious<br />

threat for potato cultivation, because it<br />

provides for greater variation in the<br />

pathogen population. Laboratory tests and<br />

field studies have shown that the sexuallyreproducing<br />

populations can be considerably<br />

more aggressive than their asexual<br />

predecessors. Research has shown that<br />

the new, mixed populations adapt more<br />

rapidly to temperatures that are normally<br />

unfavourable for Phytophthora; the<br />

pathogen used to be inviable at temperatures<br />

below 10°C and above 25°C, but<br />

this is not the case for the new variants.<br />

Newly-collected isolates are also often<br />

able to survive better on the tuber, as they<br />

tend to damage the tuber less severely: the<br />

tuber rots less rapidly, and is consequently<br />

less easy to sort out on the basis of external<br />

symptoms.<br />

The new population also has a considerably<br />

shorter latent period, meaning that<br />

the life-cycle of Phytophthora infestans<br />

can be completed more rapidly than<br />

before. This, in turn, allows the fungus to<br />

adapt more rapidly through sexual reproduction.<br />

Under favourable conditions, two<br />

generations a week are now possible, compared<br />

with one generation before. It is thus<br />

important to have short intervals in the<br />

spraying programme in areas where<br />

oospores are being formed.<br />

Further threats presented by the new,<br />

mixed populations include the fact that<br />

they often have high spore production<br />

rates, and can break through varietal genetic<br />

resistance more easily. In addition, they<br />

have a broader range of host plants compared<br />

with the ‘old’ Phytophthora: for<br />

example, it is known that the new mixed<br />

populations can also infect green night-<br />

Phytophthora infestans – symptoms<br />

If “Phytophthora-weather“ prevails,<br />

potato tubers can be infected as soon<br />

as they are formed in the middle of<br />

the season.<br />

Above-ground parts of the plant must be<br />

adequately protected right from the start,<br />

in order to prevent inoculum from being<br />

washed down into the soil.<br />

Severe infection of foliage leads to<br />

significant yield losses.<br />

1/08 COURIER 19

Life cycle of Phytophthora infestans<br />

Sporangia<br />

release zoospores<br />

Movement of zoospores on<br />

the leaf surface<br />

Sporangium<br />

Infected tubers<br />

as an inoculum<br />

source for primary<br />

infections<br />

Direct<br />

germination<br />

of sporangia<br />

Zoospores<br />

encyst and<br />

germinate<br />

Mycelial growth<br />

Infection of tubers<br />

via sporangia<br />

Formation of a sporangial lawn<br />

on the underside of the leaf.<br />

shade (Solanum sarrachoides) and rocket<br />

leaf (dense-thorn bitter apple Solanum<br />

sisymbriifolium), which can then act as<br />

host plants for inoculum.<br />

More action against<br />

Phytophthora necessary<br />

Keeping Phytophthora infestans under<br />

control will require more vigilance and<br />

action towards prevention and eradication<br />

than before, says Schepers. He emphasises<br />

that prevention always begins with the<br />

elimination of sources of early infection,<br />

for example by covering cull piles early on,<br />

and by removing volunteer plants. Moreover,<br />

early foci of Phytophthora infection<br />

must be suppressed as rapidly as possible.<br />

In the Netherlands, a system of presenting<br />

farmers with yellow and red cards has been<br />

in use for several years to encourage this:<br />

potato growers who do not have their<br />

cull piles covered by April 15 are given a<br />

yellow card; the same applies to growers<br />

with many volunteer plants in their fields,<br />

and to growers who do not control the<br />

early foci, or do so only inadequately. If<br />

the growers have not acted within 3 days<br />

of receiving the yellow card, the consequences<br />

are a red card and a fine.<br />

A second factor that can curb the<br />

disease is extended crop rotation. Research<br />

has shown that oospores can survive in the<br />

soil for 3 to 4 years. If a second crop of<br />

potatoes is grown within this period (or if<br />

volunteer plants are allowed to grow on<br />

the same plot of land), early infection can<br />

develop from oospores.<br />

Choice of variety is a further important<br />

factor in keeping Phytophthora in check.<br />

Infection occurs considerably less rapidly<br />

in highly-resistant varieties. With regard to<br />

crop protection, the spraying strategy must<br />

be tightened up where mixed populations<br />

are present, in order to counter the increased<br />

risk of infection. Among other<br />

things, this can mean starting spraying<br />

earlier, with shorter intervals between<br />

applications, so that the pathogen has less<br />

chance to develop. In addition, where there<br />

is high disease pressure, more attention<br />

will have to be paid to combining different<br />

active substances (modes of action) than<br />

is the case at present. Schepers draws<br />

attention to the critical issue that active<br />

substances increasingly have a limited<br />

number of applications. “With the more<br />

aggressive Phytophthora being present,<br />

greater knowledge is needed in order to<br />

develop a watertight strategy.” ■<br />

Written by: Han Hammink<br />

20 COURIER 1/08

New combination of active<br />

substances against potato blight<br />

The new Infinito ® has already established itself in the<br />

market as a highly-effective potato fungicide – within<br />

only a few years of its introduction. The first registrations<br />

were obtained in 2006; in the meantime, Infinito can be<br />

used to control potato late blight (Phytophthora infestans)<br />

in nearly twenty countries. The latest registration was<br />

granted in Japan at the beginning of 2008. The product<br />

will be marketed there under the trade name Reliable ® .<br />

Bad news for potato blight, but good news for Infinito:<br />

in the last few years, the product has been able to demonstrate<br />

its strength in controlling the disease on aboveground<br />

parts and tubers, thereby protecting the entire potato<br />

plant. To achieve this, it draws on the combination of<br />

two highly effective active substances: propamocarb-HCl<br />

und fluopicolide.<br />

Fluopicolide is a new active substance from <strong>Bayer</strong><br />

<strong>CropScience</strong>’s Research Unit. It has a unique mode of action<br />

that leads to a rapid destabilisation of fungal cells.<br />

Products based on this innovative active substance stand<br />

out by virtue of the long-term, consistently high level of<br />

protection they provide to crops, as well as through their<br />

favourable environmental profile.<br />

Fluopicolide’s new mode of action<br />

Fluopicolide acts by disrupting the pathogen’s cell structure.<br />

It inhibits the formation of spectrin-like proteins that<br />

are assumed to play an important role in the stabilisation<br />

of the pathogen’s cells. This unique mode of action is<br />

effective against all of the most critical stages of the<br />

pathogen’s life-cycle. However, fluopicolide’s main target<br />

is the zoospore stage: the spores stop moving within seconds<br />

of coming into contact with the active substance;<br />

then they swell-up, and, eventually, burst. Fluopicolide<br />

also reduces sporulation and suppresses the growth of<br />

fungal mycelia within plant tissues. Moreover, it inhibits<br />

both direct and indirect sporangial germination.<br />

Fluopicolide’s partner in Infinito is the time-tested<br />

active substance propamocarb-HCl, which has been on<br />

the market for 30 years now. Propamocarb-HCl influences<br />

fatty acid synthesis, so it has a completely different mode<br />

of action from fluopicolide. The two active substances<br />

complement each other very well to provide the effective,<br />

long-term protection that Infinito affords. Both possess<br />

systemic and trans-laminar distribution properties. Active<br />

substance taken up by the stem is thus transported to other<br />

parts of the plant, which means that newly-grown plant<br />

tissues can also be protected from infection. ■<br />

Late blight: the thread-like mycelium of the pathogen<br />

Phytophthora infestans has formed a network within<br />

the tissues of the potato plant. The <strong>Bayer</strong> active substance<br />

fluopicolide is particularly active against the zoospores<br />

(contained in the capsules at the ends of the mycelial threads)<br />

that help the late blight pathogen to spread.<br />

1/08 COURIER 21

Colorado potato beetle<br />

and aphids – threatening,<br />

but manageable<br />

A threat to potato crops throughout<br />

the world: the Colorado potato beetle<br />

(Leptinotarsa decemlineata)<br />

Along with leaf diseases, pests represent a serious risk<br />

for potato growers around the world: they can reduce<br />

tuber quality significantly, and, at worst, they can destroy<br />

entire harvests – that is, if they aren’t stopped in time.<br />

The danger can be managed through preventative<br />

measures and with the aid of effective <strong>Bayer</strong> products<br />

such as Biscaya ® and Proteus ® .<br />

22 COURIER 1/08

From yield reduction to total yield<br />

loss – pests such as the Colorado potato<br />

beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata) and<br />

aphids (e.g. Myzus persicae, Aulacorthum<br />

solani, Macrosiphum euphorbiae), cicadas,<br />

thrips, nematodes and potato moths are endemic<br />

– and threatening – in almost all of<br />

the traditional areas of potato cultivation.<br />

The Colorado potato beetle and its larvae,<br />

with their almost insatiable appetites, can<br />

eat continuously and are capable of laying<br />

waste to entire fields. In contrast, aphids<br />

do not cause damage directly through their<br />

feeding, but rather as so-called vectors of<br />

viruses which they can transfer every time<br />