Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

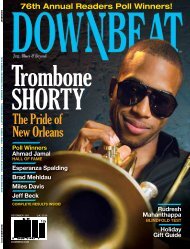

Dick Hyman<br />

Subjective<br />

& Personal<br />

By Aaron Cohen // Photo by Jack Vartoogian/FrontRowPhotos<br />

It takes a certain amount of confidence, or nerve, to attach<br />

possessive punctuation to a hundred years of an instrument’s<br />

evolution. But sometimes that apostrophe mark belongs there<br />

because the musician in front of it has not just lived through,<br />

but played a part in, those 10 decades of changes. That would<br />

be the case with the five-CD/one-DVD survey Dick Hyman’s<br />

Century Of Jazz Piano (Arbors).<br />

The collection (originally released on<br />

CD-ROM in 1997) is Hyman’s admittedly subjective<br />

and personal survey of jazz piano history.<br />

That “personal” encompasses a lot. Throughout<br />

the musical and video lessons, Hyman demonstrates<br />

ragtime’s syncopation and boogie-woogie’s<br />

loping octaves, describes how he believes<br />

Thelonious Monk’s compositions should work<br />

as improvisational vehicles and addresses Cecil<br />

Taylor’s rapid percussive attack. All of which<br />

provides only a few glimpses into Hyman’s own<br />

multifaceted career and why, at 84, he continues<br />

to inspire generations of proteges.<br />

“I’ve never had a greater teacher than him,<br />

and he continues to teach me,” said pianist Bill<br />

Charlap. “Most importantly, his beautiful touch,<br />

and very unique and individual harmonic perspective.<br />

Dick’s in his eighties, practices every<br />

day and sounds great. His lust for music never<br />

diminishes. He never sits back on his laurels; he’s<br />

always discovering and doing something new.”<br />

That desire is why Hyman continues to perform<br />

and write so energetically. It’s also why his<br />

earlier works are still sought. He plays around<br />

his Florida home for the most part, but occasionally<br />

returns to the New York club scene,<br />

where he took part in jazz’s biggest changes of<br />

the 1940s during his off hours as a busy session<br />

musician. His wide interests are also why he<br />

has distinctive followings that don’t even know<br />

of the other camp’s existence: Hyman’s lively<br />

and impeccable presentation of early stride<br />

and proto-swing styles has made him an honored<br />

guest at such historic-minded events as the<br />

Bix Beiderbecke Festival in Davenport, Iowa.<br />

This summer, he presented new classical chamber<br />

music scores that reshaped one of his earlier<br />

compositions. At the same time, DJs and electronic<br />

music mavens have been scouring Ebay<br />

and other crate-diggers’ outlets for his innovative,<br />

sometimes intentionally funny, synthesizer<br />

recordings of the 1960s. Cinephiles are also<br />

familiar with his name, which appeared on dozens<br />

of movie scores during the ’80s and ’90s.<br />

Even with this still-active career, Hyman<br />

isn’t given to introspection or expounding too<br />

much on any wider, deeper meaning of his<br />

music. As the Century project shows, he’s more<br />

given to direct explanations of how the music<br />

works. But, when prodded, Hyman will give a<br />

simple reason for his continued determination.<br />

“I have to keep explaining to my retired<br />

friends down here, you don’t stop doing<br />

this,” Hyman said a few months before the<br />

Beiderbecke festival in August. “You keep doing<br />

it until you can’t do it anymore.”<br />

Or, as Hyman shows, just keep building on<br />

what began in the late-’40s. Coming from a musical<br />

family, he was a humanities major at Columbia<br />

University and after a stint in the Navy took some<br />

classes outside of college with his uncle, Anton<br />

Rovinsky, a classical recitalist. “He began to show<br />

me the subtleties of expression and composition<br />

in the Beethoven sonatas—that stayed with me,”<br />

Hyman said. “Matters of touch. Things a good<br />

teacher would show you, not just running through<br />

and memorizing pieces, but how they work and<br />

how to make them sound well.”<br />

But it was 12 lessons he won after entering a<br />

radio contest that made as much of an impact.<br />

Teddy Wilson was the first-prize teacher. (With<br />

uncanny memory, Hyman added that if he had<br />

come in second place, then he would have studied<br />

with Mary Lou Williams.)<br />

“Teddy was a lovely man, very generous, and<br />

he gave me my complete philosophy,” Hyman<br />

recalled. “I said, ‘I really play OK sometimes,<br />

and other times I feel I’m not making it at all,<br />

36 DOWNBEAT SEPTEMBER 2011