Course Handbook - Faculty of History - University of Cambridge

Course Handbook - Faculty of History - University of Cambridge

Course Handbook - Faculty of History - University of Cambridge

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

0<br />

<strong>Course</strong> <strong>Handbook</strong><br />

MPHIL IN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL HISTORY<br />

2010-11

List <strong>of</strong> Contents<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

Page No.<br />

1 CONTACT POINTS IN THE FACULTY<br />

1.1 The MPhil Office 1<br />

1.2 The MPhil in Economic and Social <strong>History</strong> - administration 1<br />

1.3 MPhil Update 1<br />

1.4 Postgraduate administration within the <strong>Faculty</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>History</strong> 1<br />

1.5 How the administration works for the MPhil in Economic and Social 2<br />

<strong>History</strong>; whom to contact about what and when<br />

2 THE COURSE<br />

2.1 Residence requirements 3<br />

2.2 Overview <strong>of</strong> <strong>Course</strong> 3<br />

2.2.1 Introduction to Research Resources in <strong>History</strong> 3<br />

2.2.2 Part I 3<br />

2.2.3 Part II 5<br />

2.2.4 MPhil Classes and Lectures 6<br />

2.2.5 Research seminars in Economic and Social <strong>History</strong> 7<br />

2.3 Assessment Procedures 8<br />

2.3.1 Part I 8<br />

2.3.2 Part II 9<br />

2.4 Advanced <strong>Course</strong>s 10<br />

2.5 Presentation and Submission <strong>of</strong> Essays and Dissertation 13<br />

2.6 Deadlines for Submission 14<br />

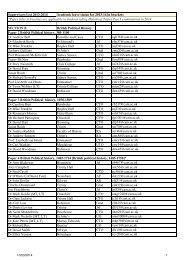

APPENDIX A: LIST OF ACADEMIC STAFF ASSOCIATED 15<br />

WITH THE MPHIL<br />

APPENDIX B: MARKING AND EXAMINING SCHEME 17<br />

APPENDIX C: NOTES ON THE APPROVED STYLE 25<br />

FOR MPHIL DISSERTATIONS

INTRODUCTION<br />

Welcome to the MPhil in Economic and Social <strong>History</strong>. We hope your time here will prove to be both<br />

enjoyable and worthwhile. Graduates can sometimes feel disoriented in <strong>Cambridge</strong> for the first few weeks.<br />

This handbook is intended to assist you in settling into the MPhil. For information about contact points<br />

within both the university and faculty, library and computing facilities, supervision, graduate training,<br />

financial assistance, maps and useful web addresses, please consult the <strong>Faculty</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>History</strong> General<br />

Graduate <strong>Handbook</strong> 2010.<br />

Please make sure that you attend the induction meeting for all MPhil in<br />

Economic and Social <strong>History</strong> students at 9.00 am on Wednesday 6 October in<br />

the <strong>Faculty</strong> Board Room (1 st floor) <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Faculty</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>History</strong><br />

Please bring this course handbook, and the General Graduate <strong>Handbook</strong>, with you to the induction<br />

meeting.<br />

I look forward to meeting you.<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor MJ Daunton<br />

Chairman, MPhil in Economic and Social <strong>History</strong>

1 CONTACT POINTS IN THE FACULTY<br />

1.1 The MPhil Office<br />

Your main point <strong>of</strong> contact in the <strong>History</strong> <strong>Faculty</strong> (on West Road) will be Miss Tessa Blackman, the<br />

administrator for the MPhil in Economic and Social <strong>History</strong>, in the MPhil Office. This is on the 4 th<br />

floor <strong>of</strong> the <strong>History</strong> <strong>Faculty</strong> building. You will visit this <strong>of</strong>fice quite <strong>of</strong>ten; all essays and<br />

dissertations as well as titles are handed in here.<br />

Tel. (7)48152 or e-mail ecsoc@hist.cam.ac.uk.<br />

The <strong>of</strong>fice is open Mondays to Thursdays: 9am to 5pm and Fridays 9am to 4.30pm. THE MPHIL<br />

OFFICE IS CLOSED FROM 1PM – 2 PM (Monday – Friday).<br />

1.2 The MPhil in Economic and Social <strong>History</strong> – administration<br />

The Sub-Committee for this MPhil consists <strong>of</strong> senior academics. It is the body which oversees the<br />

running <strong>of</strong> the programme, under the ultimate authority <strong>of</strong> the Degree Committee for the <strong>Faculty</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>History</strong>. The current Academic Secretary is Dr N. Mora-Sitja. If you need to contact her, you<br />

should do so through the MPhil Office. Most members <strong>of</strong> the sub-committee, including the<br />

Academic Secretary, are based in their Colleges.<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor MJ Daunton, Chairman<br />

Dr N Mora-Sitja, Academic Secretary<br />

Dr JC Muldrew<br />

Dr S Horrell<br />

Dr L Shaw-Taylor<br />

Miss T Blackman, Administrative Secretary<br />

<strong>Faculty</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>History</strong> / Trinity Hall<br />

<strong>Faculty</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>History</strong>/ Downing College<br />

<strong>Faculty</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>History</strong> / Queens’ College<br />

<strong>Faculty</strong> <strong>of</strong> Economics<br />

<strong>Faculty</strong> <strong>of</strong> Geography<br />

<strong>Faculty</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>History</strong>, MPhil Office<br />

(email ecsoc@hist.cam.ac.uk)<br />

1.3 MPhil Update<br />

The Degree Committee Office regularly produces an MPhil Update, which is circulated by email<br />

only, to all MPhil students. A copy <strong>of</strong> the MPhil Update is also put on the Graduate Noticeboard<br />

(located in the <strong>Faculty</strong>'s Graduate Research Room) and on the <strong>Faculty</strong>’s website. Previous editions<br />

<strong>of</strong> the MPhil Update can be viewed on the <strong>History</strong> <strong>Faculty</strong>'s website. It is important that you read the<br />

MPhil Update because it contains up-to-date information regarding funding, events and issues that<br />

have been notified to the Degree Committee Office.<br />

1.4 Postgraduate Administration within the <strong>Faculty</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>History</strong><br />

The <strong>Faculty</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>History</strong> has two <strong>of</strong>ficers responsible for Graduate Studies, the Director <strong>of</strong> Graduate<br />

Studies and the Director <strong>of</strong> Graduate Training. The Director <strong>of</strong> Graduate Studies is the executive<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficer in charge <strong>of</strong> the Degree Committee Office and the Director <strong>of</strong> Graduate Training is the<br />

executive <strong>of</strong>ficer in charge <strong>of</strong> the MPhil Office. The latter is responsible for monitoring all MPhil<br />

courses administered by the <strong>Faculty</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>History</strong>. He oversees matters relating to MPhil students from<br />

admission through to examination. He reports directly to the Degree Committee <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Faculty</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>History</strong>, which is the ultimate authority for all decisions affecting graduate students. The current<br />

Director <strong>of</strong> Graduate Training is Dr Carl Watkins.<br />

Chairman, <strong>History</strong> Degree Committee<br />

Director <strong>of</strong> Graduate Studies<br />

Director <strong>of</strong> Graduate Training<br />

Dr M Goldie<br />

Dr J Chatterji<br />

Dr C Watkins, email: graduatestudies@hist.cam.ac.uk<br />

1

Senior Secretary, <strong>History</strong> Degree<br />

Committee<br />

Miss S M Willson – tel. 335305 email:<br />

degree-committee@hist.cam.ac.uk<br />

The Degree Committee Office deals with all matters relating to postgraduate funding (both PhD and<br />

MPhil) therefore, queries and questions about funding for MPhil and PhD courses should be<br />

addressed to the Degree Committee Office: <strong>History</strong> <strong>Faculty</strong> Building, West Road, <strong>Cambridge</strong>, CB3<br />

9EF.<br />

1.5 How the administration works for the MPhil in Economic and Social <strong>History</strong>; whom to contact<br />

about what and when<br />

Normally, you are expected first to approach your supervisor about matters relating to your<br />

academic work at <strong>Cambridge</strong>. If you have not already done so, you should contact your supervisor<br />

to arrange a meeting as soon as possible. The supervisor’s responsibility is to work closely with you<br />

to prepare you for writing your MPhil dissertation.<br />

Non-academic questions should be addressed to the Graduate Tutor <strong>of</strong> your College, who will<br />

normally be the best person to approach about visa and passport problems, dealings with grant<br />

awarding bodies, and housing and financial problems in general. The Degree Committee does not<br />

deal with these sorts <strong>of</strong> issues.<br />

Queries about the <strong>Faculty</strong>’s Graduate Training <strong>Course</strong> should be addressed to the <strong>Faculty</strong>’s Director<br />

<strong>of</strong> Graduate Training, Dr C Watkins (graduate-studies@hist.cam.ac.uk).<br />

The administration <strong>of</strong> the MPhil in Economic and Social <strong>History</strong> is managed by the MPhil Sub-<br />

Committee, but under the general oversight <strong>of</strong> the <strong>History</strong> <strong>Faculty</strong> Degree Committee, which has<br />

responsibility for all the <strong>Faculty</strong>’s postgraduate programmes. As Academic Secretary for the MPhil,<br />

Dr Natalia Mora-Sitja handles the day-to-day administrative work <strong>of</strong> the programme, and there may<br />

be occasions during your time here when an informal conversation with the Academic Secretary <strong>of</strong><br />

the MPhil may lead to the quick solution <strong>of</strong> some <strong>of</strong> the problems affecting your work. The<br />

Academic Secretary is here to give you advice about your work in addition to assistance available to<br />

you from the academic personnel with whom you are in direct contact. However, many important<br />

items <strong>of</strong> business such as a change <strong>of</strong> supervisor, approving dissertation titles, leave to continue to<br />

the PhD, appointing examiners and scrutinizing examination results are formal, and must be handled<br />

by the MPhil Sub-Committee and/or the Degree Committee. Because Sub-Committee meetings<br />

take place only two or three times a term, it is important for you to deal with administrative<br />

requests in a timely manner.<br />

Other questions about <strong>Faculty</strong> matters can be addressed to Miss T Blackman, the Administrative<br />

Secretary in the MPhil Office who will be happy to try to answer questions. Please e-mail her with<br />

your questions in the first instance on ecsoc@hist.cam.ac.uk. If you do not yet have access to e-mail<br />

(although all research students are allocated an e-mail address and expected to use it), the <strong>of</strong>fice’s<br />

telephone number is 748152 (or 48152 if you are using the university telephone network). Finally, in<br />

some delicate cases you might wish to seek the help <strong>of</strong> an Ombudsperson, see the General Graduate<br />

<strong>Handbook</strong> for information.<br />

2 THE COURSE<br />

2.1 Residence Requirements<br />

The academical year in <strong>Cambridge</strong> is divided into three terms, Michaelmas, Lent and Easter; in each<br />

term, the teaching takes place only in the nine-week period known as ‘Full Term’. The dates for the<br />

current year are Michaelmas Term: Tuesday 5 October - Friday 3 December 2010; Lent Term:<br />

Tuesday 18 January - Friday 18 March 2011; Easter Term: Tuesday 26 April - Friday 17 June 2011.<br />

The <strong>University</strong> requires that all students ‘keep’ three terms <strong>of</strong> residence before they can be awarded<br />

a degree.<br />

2

During the Christmas and Easter Vacations lectures and classes do not occur and undergraduates are<br />

not in residence. Graduate students are required to remain in residence continuously throughout the<br />

academical year, and are expected to work on their research essays and dissertation during the<br />

Christmas and Easter ‘vacations’, apart perhaps from brief holiday breaks. Residing in <strong>Cambridge</strong><br />

means, for research students and those taking most other graduate courses, living within 10 miles<br />

from the centre <strong>of</strong> the city. (It is your College which must certify to the <strong>University</strong> that you have<br />

fulfilled the residence requirements. If you have further questions, or need fuller information, you<br />

should contact your College authorities.)<br />

It cannot be emphasised too strongly that the MPhil course has a very tight timetable, and that<br />

it is vital that you work consistently throughout your course.<br />

2.2 Overview <strong>of</strong> <strong>Course</strong><br />

2.2.1 Introduction to Research Resources in <strong>History</strong><br />

2.2.2 Part I<br />

NOTE: THESE COURSES ARE LISTED IN A SEPARATE BOOKLET ENTITLED<br />

GRADUATE TRAINING HANDBOOK<br />

This series <strong>of</strong> classes for all graduate students is designed to help students to discover what<br />

printed and non-printed sources exist anywhere in the world relating to their fields <strong>of</strong><br />

interest. The course <strong>of</strong>fers lectures/classes on topics such as ‘Preparing a Bibliography’,<br />

‘Reading early printed books’, ‘Oral history’, ‘Images’, ‘<strong>History</strong> and literature’, ‘Working<br />

on Early Modern and Modern British Records’, ‘Locating Research Materials on<br />

Continental European Research Topics’, ‘Locating Research Materials on Extra-European<br />

Research Topics’. There are sessions devoted to the resources specifically in <strong>Cambridge</strong>,<br />

including the <strong>University</strong> Library, the collections <strong>of</strong> the Royal Commonwealth Society, the<br />

<strong>Faculty</strong> Library, the Churchill College Archives Centre and in other local research centres.<br />

A visit to the National Archive is also arranged.<br />

Central Concepts in Economic and Social <strong>History</strong><br />

This class meets once a week on Mondays at 10am to 12 throughout Michaelmas. It consists<br />

<strong>of</strong> a series <strong>of</strong> seminars/classes in two main areas: (a) Social Theory and Social <strong>History</strong>, and<br />

(b) Economic Theory and Economic <strong>History</strong>, covering such topics as social stratification,<br />

households, family and kinship, health and welfare, gender, social capital, neoclassical<br />

economic growth theory, technological change, consumer behaviour and consumption,<br />

demography, and globalisation.<br />

Introductory reading:<br />

D.C. Coleman, <strong>History</strong> and the Economic Past (1987)<br />

D.A. Redman, Economics and the Philosophy <strong>of</strong> Science (1991)<br />

A. Giddens, Sociology (1989)<br />

M. Olson, The Logic <strong>of</strong> Collective Action (1965)<br />

C.I. Jones, Introduction to Economic Growth (1998)<br />

E.L. Jones, The European Miracle (1987)<br />

R.D. Putnam, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival <strong>of</strong> American Community (New<br />

York: 2000)<br />

M. Granovetter and R. Swedberg (eds.), The Sociology <strong>of</strong> Economic Life (1992)<br />

P. Joyce (ed.), Class (1995)<br />

J. Scott, Gender and the Politics <strong>of</strong> <strong>History</strong> (1988)<br />

R. Fox (ed.), Technological Change: Methods and Themes in the <strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> Technology<br />

(1998)<br />

M. Anderson, Approaches to the <strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> the Western Family, 1500-1914 (1980)<br />

J. Elster (ed.), Rational Choice (1990)<br />

3

M. Foucault, Power/Knowledge (ed. C. Gordon, 1980)<br />

L. Hunt (ed.), The New Cultural <strong>History</strong> (1989)<br />

P. Burke, <strong>History</strong> and Social Theory (1992)<br />

Q.R.D. Skinner (ed.), The Return <strong>of</strong> Grand Theory in Human Sciences (1990)<br />

W. Kula, The Problems and Methods <strong>of</strong> Economic <strong>History</strong> (2001)<br />

Quantitative Research in <strong>History</strong><br />

This class meets once a week in Lent (for 3 weeks) on Mondays at 10am to 12. It consists <strong>of</strong><br />

a series <strong>of</strong> classes to review and discuss the use <strong>of</strong> quantitative methods by economic and<br />

social historians. They are not formally assessed within the course, but attendance is<br />

compulsory.<br />

Introductory reading:<br />

C. Feinstein and M. Thomas, Making <strong>History</strong> Count (2002)<br />

P. Sharpe, <strong>History</strong> by Numbers: an Introduction to Quantitative Approaches (2000)<br />

W.O. Aydelotte, A.G. Bogue, and R.W. Fogel (eds.), The Dimensions <strong>of</strong> Quantitative<br />

Research in <strong>History</strong> (1972)<br />

Social Sciences Research Methods <strong>Course</strong> (SSRMC)<br />

These are a set <strong>of</strong> research training courses in the social sciences organised on an<br />

interdepartmental basis between three administrative Schools <strong>of</strong> the <strong>University</strong>: the School<br />

<strong>of</strong> Humanities and Social Sciences, the School <strong>of</strong> Physical Sciences, and the Judge Business<br />

School. The programme is a shared platform for providing research students with a broad<br />

range <strong>of</strong> quantitative and qualitative research methods skills that are relevant across the<br />

social sciences.<br />

The programme <strong>of</strong>fered by the Joint Schools (JSSS) consists <strong>of</strong> a series <strong>of</strong> core modules and<br />

open access seminars. The core modules are grouped in three categories: Foundations in<br />

Statistics, Advanced Statistics, and Qualitative Methods. They focus on giving students<br />

basic IT skills and introducing them to statistical, quantitative and qualitative research<br />

design, providing the foundations for a research career in the social sciences.<br />

The courses <strong>of</strong>fered by the Joint Schools run through Michaelmas and Lent Terms, with a<br />

deadline to submit the relevant workbooks in late April. The modules are taught through a<br />

combination <strong>of</strong> lectures and practical classes by staff from several <strong>University</strong> Departments<br />

and Faculties.<br />

PLEASE REFER TO THE JOINT SCHOOLS HANDBOOK FOR DETAILS, DATES<br />

AND DESCRIPTION OF THE COURSES.<br />

Students doing the MPhil in Economic and Social <strong>History</strong> are entitled to take as many<br />

modules as they wish, but in order to satisfy the requirements <strong>of</strong> the MPhil they must<br />

attend and submit the workbooks/assignments <strong>of</strong> at least five modules, as follows:<br />

• SPSS and Descriptive Statistics (four sessions, Michaelmas)<br />

o 1. Introduction to SPSS and basic statistical concepts<br />

o 2. Statistical models and elementary data analysis with SPSS<br />

o 3. Management <strong>of</strong> data and output<br />

o 4. Getting the best out <strong>of</strong> SPSS<br />

• Linear Regression (four sessions, Lent)<br />

o 1. Review <strong>of</strong> covariance, correlations and comparison <strong>of</strong> means.<br />

Introduction to bivariate linear regression<br />

o 2. Multivariate linear regression<br />

o 3. Assessing regression models.<br />

o 4. Overview and summary <strong>of</strong> topics in regression<br />

4

• Comparative Historical Methods (four sessions, Michaelmas)<br />

o 1. Classics<br />

o 2. Justifications I<br />

o 3. Justifications II<br />

o 4. State <strong>of</strong> the Art<br />

• Introduction to database design and use: Access (three sessions, Lent)<br />

o 1. Introduction to designing a relational database<br />

o 2. Creating tables and queries<br />

o 3. Useful operations<br />

• One other module <strong>of</strong> your choice<br />

Students are advised to check with their supervisors whether it would be advisable to attend<br />

other modules within the Social Science Research Methods <strong>Course</strong> relevant to their<br />

research, and they are encouraged to take as many modules as they wish beyond those<br />

required for the MPhil. For students with no prior training in statistics, it is advisable to<br />

attend the ‘Foundations in Statistics’ module (three sessions, Michaelmas).<br />

Advanced <strong>Course</strong>s in Economic and/or Social <strong>History</strong><br />

Two advanced papers from the following list <strong>of</strong> subjects must be taken over the course <strong>of</strong><br />

Michaelmas and Lent Terms.<br />

1) Topics in the history <strong>of</strong> economic and social thought<br />

2) British industrialization in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries<br />

3) Institutions and development (taught by the MPhil in Development Studies)<br />

4) International Political Economy since 1945: Bargaining over Ideas and Interests<br />

5) The origins and spread <strong>of</strong> financial capitalism<br />

6) Gender and development<br />

7) Language and society (a course taught by the MPhil in Early Modern <strong>History</strong>)<br />

8) The economic policies <strong>of</strong> right-wing dictatorships in the era <strong>of</strong> mass politics<br />

2.2.3 Part II<br />

Dissertation<br />

The formation and execution <strong>of</strong> the dissertation project on a subject in economic and/or<br />

social history is the largest and most important part <strong>of</strong> the student’s work in the MPhil in<br />

Economic and Social <strong>History</strong>. It is expected that it will account for approximately 60 per<br />

cent <strong>of</strong> the student’s time over the eleven months <strong>of</strong> the course. Candidates are required to<br />

design, research and write up a dissertation on a subject in the fields <strong>of</strong> economic and/or<br />

social history that has been approved by the <strong>Faculty</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>History</strong>. The dissertation must be<br />

between 15,000 and 20,000 words in length, exclusive <strong>of</strong> footnotes, references and<br />

bibliography. Candidates must demonstrate that they can present a coherent historical<br />

argument based upon a secure knowledge and understanding <strong>of</strong> primary sources and they<br />

will be expected to place their research findings within the existing historiography <strong>of</strong> the<br />

field within which their subject lies. The dissertation must represent a contribution to<br />

knowledge, considering what may be reasonably expected <strong>of</strong> a capable and diligent student<br />

after eleven months <strong>of</strong> MPhil level study.<br />

Dissertation Titles must be submitted to the MPhil Office by 12 noon on Friday 14<br />

January 2010<br />

Please see Appendix B ‘MPhil in Economic and Social <strong>History</strong> – Marking and Examination<br />

Scheme’ and Appendix C ‘Notes on the Approved Style for MPhil Dissertations’.<br />

5

2.2.4 MPhil Classes and Lectures<br />

The schedule below is just an orientation; it does not include for example Advanced Papers, which<br />

are scheduled by the course organisers, or the fifth module <strong>of</strong> the JSSS, which is the students’<br />

choice. Students are advised to double-check the arrangements for each course at the beginning <strong>of</strong><br />

the year.<br />

MICHAELMAS TERM 2010<br />

Time Lecture Venue<br />

Mondays 10.00-12.00<br />

Starting 11 October<br />

(eight classes)<br />

Central Concepts in Economic<br />

and Social <strong>History</strong><br />

<strong>History</strong> <strong>Faculty</strong>, Room 7<br />

Wednesday 6 October, 16.00-<br />

17.00<br />

SSRMC<br />

General Introduction<br />

Babbage Lecture Theatre,<br />

New Museums Site<br />

Mondays, 16.00-18.00 OR<br />

Tuesdays, 14.00-16.00<br />

Starting 8 or 9 November<br />

Wednesdays, 14.00-16.00<br />

Starting 13 October<br />

Thursdays, 5-6.30pm<br />

SSRMC<br />

SPSS and Descriptive<br />

Statistics<br />

SSRMC<br />

Comparative Historical<br />

Methods<br />

Core Seminar in Economic and<br />

Social <strong>History</strong><br />

Titan Rooms, New<br />

Museums Site<br />

Lecture Room 1, Mill<br />

Lane<br />

Trinity Hall<br />

LENT TERM 2011<br />

Time Lecture Venue<br />

Mondays 10.00-12.00 Quantitative research in <strong>History</strong> <strong>Faculty</strong>, Room 7<br />

starting 24 January<br />

<strong>History</strong><br />

Mondays, 14.00-16.00 OR SSRMC<br />

Titan Rooms, New Museums<br />

16.00-18.00<br />

Linear Regression<br />

Site<br />

Starting 21 February<br />

Monday/Tuesday/Wednesday,<br />

14.00-17.00<br />

starting 17 January<br />

Research Methods (JSSS),<br />

Introduction to database design<br />

and use<br />

Titan Rooms, New Museums<br />

Site<br />

Mondays and Thursdays<br />

Timetable <strong>of</strong> Deadlines<br />

Research Seminars in<br />

Economic and Social <strong>History</strong><br />

Refer to Research Seminars<br />

programmes in the <strong>Faculty</strong><br />

website<br />

Submission Date<br />

for Central<br />

Concepts Term<br />

Paper<br />

Submission<br />

Date<br />

for Dissertation<br />

Titles<br />

Dates for Advanced<br />

<strong>Course</strong> Timed Essays<br />

Submission Date<br />

for Dissertation<br />

Proposal Essay<br />

Submission<br />

Date<br />

for Dissertation<br />

Friday 3<br />

December 2010<br />

Friday 14<br />

January 2011<br />

Monday 21 to Monday 28<br />

March 2011 (Submission<br />

Monday 28 March by<br />

5.00pm)<br />

Monday 9 May<br />

2011<br />

Friday 19<br />

August 2011 by<br />

12.30 pm<br />

If a viva is necessary it will generally be held in the last two weeks <strong>of</strong> September.<br />

2.2.5. Research Seminars in Economic and Social <strong>History</strong><br />

6

There are several research seminars in Economic <strong>History</strong> going on at <strong>Cambridge</strong> during Full<br />

Term: Early Modern Economic and Social <strong>History</strong>, Modern Economic and Social <strong>History</strong>,<br />

Quantitative <strong>History</strong>, <strong>History</strong> and Economics, and Medieval Economic <strong>History</strong>. These<br />

involve scholars -from both within and beyond <strong>Cambridge</strong>- presenting their research<br />

(almost invariably still unpublished) to an audience <strong>of</strong> graduate students and senior<br />

members <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Faculty</strong>, followed by an open discussion. Additionally, there is a Graduate<br />

Workshop in Economic and Social <strong>History</strong> organised by graduate students and where<br />

graduate students present their work. They are all wonderful opportunities to witness<br />

research in progress, to understand how different methodologies are applied to specific<br />

research questions, to learn about the latest research trends within the discipline and to<br />

understand how to formulate questions and participate in discussions about other people’s<br />

work, all <strong>of</strong> these important skills even on fields away from one’s own.<br />

The programs are updated early each term in the <strong>History</strong> <strong>Faculty</strong> website.<br />

Students for the MPhil in Economic and Social <strong>History</strong> are expected to attend these<br />

seminars regularly, in particular the Core Economic and Social <strong>History</strong> Seminar in<br />

Michaelmas Term (Thursdays, 5pm, Trinity Hall).<br />

2.3 Assessment Procedures<br />

2.3.1 Part I (40%)<br />

Central Concepts and Problems <strong>of</strong> Economic and Social <strong>History</strong> and Theory (10%)<br />

This is a term paper <strong>of</strong> up to 3,000 words based on questions dealing with themes discussed<br />

in the sessions, and handed in at the end <strong>of</strong> Michaelmas term. There will be approximately<br />

two questions per session. The purpose <strong>of</strong> these essays is to examine a central problem or<br />

issue discussed in the relevant secondary literature in a critical way. They should<br />

demonstrate sound knowledge <strong>of</strong> the literature in question, but should be more than a<br />

narrative summary. The essays are generally quite broad ranging and should be based both<br />

on readings listed in the individual bibliographies for each session as well as additional<br />

more specific readings supplied by the session teachers.<br />

Research Methods (10%; composed <strong>of</strong> Research Methods Training course -6%- and<br />

Dissertation Proposal Essay -4%-)<br />

Students will submit workbooks for the Research Methods Training Modules. These are<br />

marked by the instructors involved in the Joint Schools Social Science Research Methods<br />

<strong>Course</strong> on a fail, pass or high pass basis. For the purposes <strong>of</strong> its marking scheme, this MPhil<br />

adopts the following convention: fail = 55%, pass = 67%, and high pass =75%. Non<br />

submission <strong>of</strong> a workbook will count as a fail on that workbook. Students must receive a<br />

majority <strong>of</strong> pass marks on their workbooks to pass this part <strong>of</strong> the course. A majority <strong>of</strong><br />

high passes will result in a mark <strong>of</strong> 75%. There is also an essay required for some <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Modules. NOTE: FOR THE ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL HISTORY MPHIL THIS IS<br />

THE SAME AS THE DISSERTATION PROPOSAL ESSAY BELOW, in which<br />

students should endeavour to apply conceptual knowledge learned in the Research Methods<br />

sessions to their own research plans. It should be handed in to the MPhil <strong>of</strong>fice in the<br />

<strong>History</strong> <strong>Faculty</strong>.<br />

Dissertation Proposal Essay (4%)<br />

This essay, <strong>of</strong> up to 4,000 words, is intended to help students define the scope <strong>of</strong> the<br />

dissertation as well as the sources and methods to be adopted. It is primarily an<br />

historiographical investigation <strong>of</strong> the secondary literature, which contextualises the topic<br />

which is to be investigated, in the dissertation. This is done by drawing on a relevant aspect<br />

<strong>of</strong> the qualitative and quantitative methods teaching in the joint schools’ courses. The<br />

approach should place the planning <strong>of</strong> research in a broad context that defends choices <strong>of</strong><br />

7

methods. The student should also deal with how their proposed research will attempt to<br />

answer the questions arising from the historiographical review, but it is not intended that the<br />

course <strong>of</strong> research should be described in detail here (this should be done with the<br />

dissertation supervisor).<br />

There will be a session where students will have a 20 minute presentation on this essay to<br />

the whole group <strong>of</strong> MPhil students for feedback and discussion before it is handed in for<br />

marking. This session will take place on 28 April 2011 (in the afternoon) and the paper will<br />

be submitted approximately one week later. In these presentations, students are expected to<br />

explain to the audience what their research question is, how it contributes to existing<br />

literature on the topic, and what sources and methodology will be used.<br />

All work (essays and dissertations) apart from the Social Science Research Methods <strong>Course</strong>,<br />

is double marked. Examiners for all work award marks independently. See Appendix B for<br />

details <strong>of</strong> the marking scheme.<br />

Advanced Papers (10% each)<br />

These papers are taught using a mixture <strong>of</strong> lectures and seminars amounting to at least 16<br />

contact hours each, and are based on more specialized topics than the central concepts essay,<br />

and should be more specific. All Advanced Papers are examined in the last week <strong>of</strong> Lent<br />

Term (NOTE: The week after 'Full Term' finishes) by term papers based on the specific<br />

topics discussed in the course. Both <strong>of</strong> these essays, however, will be written during a<br />

limited time period <strong>of</strong> one week. The question papers will be picked up on Monday 21<br />

March at 9:00 and have to be handed in by 5:00 on Monday 28 March. Each essay topic will<br />

be chosen from 4 questions. These essays will be 3-4000 words in length each and will be<br />

based on a topic or topics discussed in the course, and students will be expected to cite a<br />

reasonable selection <strong>of</strong> secondary or/and primary sources discussed. Two copies <strong>of</strong> each<br />

essay are required. The essays should normally be word-processed, double-spaced, and<br />

written with footnotes and a bibliography, although examiners should take into<br />

consideration the limited amount <strong>of</strong> time available for each essay.<br />

2.3.2 Part II<br />

Any candidate who fails Part I <strong>of</strong> an MPhil course may apply to the Board <strong>of</strong> Graduate<br />

Studies for transfer to the Certificate <strong>of</strong> Postgraduate Study.<br />

Dissertation (60%)<br />

Each student is assigned to a Supervisor appointed by the <strong>Faculty</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>History</strong>. The Supervisor<br />

will be an expert in the student’s general field <strong>of</strong> dissertation work, whose role is to guide<br />

the student’s programme <strong>of</strong> study as a regular advisor for the entire year as well as advising<br />

on all aspects <strong>of</strong> the MPhil dissertation. The Supervisor should be concerned with helping<br />

students to clarify their own ideas, not to impose his or her own interests on the subject; thus<br />

it is important that students should be able to make their own interests known early on in the<br />

course. Students should not expect to be ‘spoon fed’ by their supervisors since graduate<br />

students in <strong>Cambridge</strong> are expected to have the capacity and enthusiasm for organising their<br />

own research and to work largely on their own initiative. Frequency <strong>of</strong> meetings between<br />

students and their supervisors is a matter for mutual agreement and varies according to the<br />

stage <strong>of</strong> the dissertation work and an individual’s particular needs. The level <strong>of</strong> expected<br />

supervision is one meeting every two weeks during term.<br />

Dissertations are researched and written over a five month period from April to August and<br />

should reflect research which could reasonably be expected to be done in this period.<br />

Dissertation titles must be submitted to the MPhil Office by 12 noon on Friday 14<br />

January 2011, for approval by the MPhil Sub-Committee. Titles may not be changed<br />

(even minimally) except with the written approval <strong>of</strong> the Academic Secretary, which<br />

8

must be sought in writing (by letter or e-mail). Any such request must be accompanied by<br />

confirmation that the change has been discussed with and is supported by your supervisor.<br />

While permission to change titles is not automatically granted, it does <strong>of</strong>ten happen that<br />

students need to refine their titles from those initially submitted. This is accepted practice so<br />

long as the correct procedures are followed. The above points refer to minor refinements <strong>of</strong><br />

titles. However, no substantive changes <strong>of</strong> topic area will normally be permitted once<br />

examiners have been appointed by the MPhil Sub-Committee, because examiners are<br />

appointed with expertise relevant to the topic area indicated by the original title submitted<br />

by the student. Students must therefore be sure to identify at least the broad area <strong>of</strong> their<br />

intended dissertation correctly in the original title submission.<br />

Dissertations must be submitted to the <strong>History</strong> <strong>Faculty</strong> Office before 12.30pm on<br />

Friday 19 August.<br />

Dissertations will be assessed by two examiners (excluding the supervisor), one <strong>of</strong> whom<br />

may be an external examiner, who will report independently. Dissertations will be classed<br />

according to a scale comprising Pass (60 and above), Marginal Fail (59) and Fail (58 and<br />

below).<br />

Two marks <strong>of</strong> 67 or above are normally required for a candidate to proceed to a PhD.<br />

59 A borderline mark. As it stands, this mark indicates that the dissertation<br />

fails but that the Pass/Fail qualities are very evenly balanced in the<br />

dissertation.<br />

Please refer to Appendix B ‘MPhil in Economic and Social <strong>History</strong> – Marking and<br />

Examining Scheme’ for a more detailed explanation <strong>of</strong> examining and marking procedures.<br />

2.4 Advanced <strong>Course</strong>s<br />

These courses will be taught using a mixture <strong>of</strong> lectures and seminars amounting to 16 contact hours<br />

over the course <strong>of</strong> Michaelmas and Lent Terms. Some courses are taught solely in one term or the<br />

other, and dates are usually arranged at the first session, except for ‘Institutions and development’,<br />

which has a set schedule.<br />

1) The history <strong>of</strong> economic and social thought<br />

Dr. C. Muldrew, Dr. S. Thompson and Dr. S. Reinert<br />

This course focuses upon six basic themes in the history <strong>of</strong> economic and social thought<br />

through intensive study <strong>of</strong> the writings <strong>of</strong> certain seventeenth, eighteenth- and nineteenthcentury<br />

authors: the nature <strong>of</strong> money and monetary relations (John Locke and John Law);<br />

regulation and laissez-faire (Adam Smith); economic and social reform; the Industrial<br />

Revolution; the state and social change; and the development <strong>of</strong> capitalist modernity and<br />

social theory (Marx, Weber).<br />

Introductory reading:<br />

Malynes, Gerald de, Consuetudo vel Lex Mercatoria, (London, 1622).<br />

McCulloch, J.P., A Select Collection <strong>of</strong> Early English Tracts on Commerce, (<strong>Cambridge</strong>,<br />

1954).<br />

Patrick Hyde Kelly (ed.), Locke on Money, 2 vols., (Oxford, 1991)<br />

John Law, Money and Trade Considered with a Proposal for Supplying the Nation with<br />

Money (Edinburgh, 1705).<br />

Margaret Schabas, The Natural Origins <strong>of</strong> Economics (<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Chicago Press, 2005).<br />

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Basic Political Writings, trans. Donald A. Cress (Hackett,<br />

1987).<br />

Robert C. Tucker, ed., The Marx-Engels Reader, 2nd edition (W. W. Norton, 1978).<br />

9

Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit <strong>of</strong> Capitalism, trans. Talcott Parsons<br />

(Routledge, 2001).<br />

2) British industrialization in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries<br />

Dr. S. Horrell and Dr. L. Shaw-Taylor<br />

The course considers the processes by which Britain became the first nation to overcome<br />

growth constraints and embark on a path <strong>of</strong> sustained expansion <strong>of</strong> per capita income. It<br />

looks at the roles played by increased investment and labour supply to industrial activities<br />

and changed incentives, which improved the efficiency <strong>of</strong> agriculture and promoted the<br />

development <strong>of</strong> industry. But it also emphasises the roles <strong>of</strong> country-specific institutions,<br />

such as property rights, and national cultures, such as inheritance patterns and work roles for<br />

men and women, in understanding Britain's `exceptionalism'. The course covers key debates<br />

both on the causes <strong>of</strong> industrialisation and the consequences for the people who lived<br />

through it. It looks at the following main topics:<br />

1. Industrialisation - overview and outline <strong>of</strong> main debates<br />

2. Agrarian change - enclosure, service in husbandry and rural class structure<br />

3. Agrarian change - new techniques and rising land productivity<br />

4. Revolution or evolution - trade, industry and growth<br />

5. Work and industrialisation - child labour and the emergence <strong>of</strong> the male<br />

breadwinner family<br />

6. The Poor Law and changes in the welfare system<br />

7. Industrialisation and the standard <strong>of</strong> living - qualitative assessments and<br />

quantification<br />

8. Industrialisation and women - implications for the measurement <strong>of</strong> welfare<br />

The aims <strong>of</strong> this course are to introduce students to the main debates, conceptual tools and<br />

empirical findings that are central to understanding British economic history during the<br />

Industrial Revolution.<br />

By the end <strong>of</strong> this course students should have acquired a good understanding <strong>of</strong> the key<br />

debates surrounding Britain's industrialisation and the welfare implications <strong>of</strong> the changes<br />

that occurred. They should be familiar with the various methodologies and data sources<br />

employed and have knowledge <strong>of</strong> recent empirical findings.<br />

3) Institutions and development (A course taught by the MPhil in Development Studies)<br />

Dr. S. Fennell<br />

The course looks at development processes through the lenses <strong>of</strong> a variety <strong>of</strong> institutional<br />

perspectives, ranging from the economic to the anthropological in disciplinary terms. The<br />

importance and implications <strong>of</strong> institutional analyses for development processes are<br />

identified by means <strong>of</strong> engaging with both traditional and new literatures on the role <strong>of</strong><br />

socio-political processes and their inter-relationships with economic activity. In the<br />

Michaelmas term the course will examine theoretical issues in the study <strong>of</strong> institutions using<br />

a range <strong>of</strong> disciplinary tools and illustrations <strong>of</strong> institutional success and failure from the<br />

twentieth century. In the Lent term the various competing models that have emerged in the<br />

new field <strong>of</strong> institutions are examined in the light <strong>of</strong> historical evidence on institutional<br />

performance and change. The lectures will be based on case studies and a policy analysis <strong>of</strong><br />

the different development experiences across a range <strong>of</strong> countries. The teaching in the<br />

Michaelmas term consists <strong>of</strong> one lecture and one class each week. In the Lent term, there is<br />

a schedule for both lectures and seminars. The seminars are designed to be small-group<br />

student presentations, which will allow a more free-ranging discussion <strong>of</strong> the topics covered<br />

in lectures over the two terms. There will be supervisions on key topics in weeks four and<br />

week eight <strong>of</strong> both Michaelmas and Lent terms. Supervisions will have the following<br />

format: Students will have a preliminary class with the supervisor after which they will be<br />

given a week to write a 2,000 word essay. The essays must be handed in on the scheduled<br />

date so that the supervisor has sufficient time to mark the work for the subsequent meeting<br />

with students in small groups (<strong>of</strong> five-six students) for a feedback session.<br />

10

4) International Political Economy since 1945: Bargaining over Ideas and Interests<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>. M. Daunton<br />

This course provides a unique, original, and interdisciplinary lens onto the subject <strong>of</strong><br />

International Political Economy that draws primarily on existing analytic frameworks <strong>of</strong><br />

historical institutionalism and negotiation analysis. It begins with the assumption that the<br />

current economic system cannot be understood without a close analysis <strong>of</strong> the institutional<br />

bargains that underpin the system. These bargains are not one-<strong>of</strong>f deals; most international<br />

institutions have formal and informal flexibility provisions that facilitate re-negotiation to<br />

adapt to new international imperatives, domestic interests and ideas. In this course, we will<br />

analyze the intersection between international and domestic factors, and the processes <strong>of</strong> renegotiation<br />

and adaptation, to explain the evolution <strong>of</strong> the international economic system<br />

from the post-war years to the present day.<br />

Key features <strong>of</strong> the course include a) the use <strong>of</strong> original sources (ranging from the key<br />

intellectual and policy debates over the creation and maintenance <strong>of</strong> the post-war<br />

international economic institutions, to the agreements, proposals and declarations that form<br />

the workings <strong>of</strong> these institutions today) b) the use <strong>of</strong> theories <strong>of</strong> IPE and negotiation c) an<br />

enhanced historical and theoretical understanding <strong>of</strong> “process” as an explanatory mechanism<br />

for stability and change in the global economy and d) a clear understanding <strong>of</strong> the<br />

interaction between the domestic and international levels <strong>of</strong> the economic system, based on<br />

the <strong>of</strong>ten divided worlds <strong>of</strong> theoretical versus historical approaches to IPE.<br />

The following topics are covered in the course. If there are any additional topics that<br />

students wish to cover, they should consult with Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Daunton and Dr Narlikar.<br />

I. Introduction<br />

Theoretical Approaches: Bringing together IPE and <strong>History</strong><br />

II. The Bretton Woods System: Creation, Crisis, Evolution<br />

The Bretton Woods System: Creation and Collapse<br />

The Evolution <strong>of</strong> Bretton Woods System: 1974/75-2000<br />

Currency stability and Global Imbalances<br />

III. The Multilateral Trading System: ITO, GATT, WTO<br />

The Construction <strong>of</strong> the Post-War Economic System (I): the Multilateral Trading System<br />

From the failed ITO to the GATT: A second-best solution<br />

The WTO: Creation and Crisis<br />

IV. Mainstreaming Development<br />

Competing visions and institutions<br />

V. Managing Globalization<br />

Globalization: New phenomenon or Déjà vu<br />

The Global Economy: Opportunities and constraints<br />

New Actors in the International Political Economy<br />

Managing Globalization: Building and reforming institutions<br />

Revision Session<br />

5) The origins and spread <strong>of</strong> financial capitalism<br />

Dr. D'Maris C<strong>of</strong>fman and Dr. David Chambers<br />

Historical studies <strong>of</strong> financial capitalism from the nineteenth century onwards are most <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

concerned with moments <strong>of</strong> spectacular boom and bust from whence moral lessons are<br />

drawn for contemporary audiences. Charles Mackay's classic, Extraordinary Popular<br />

Delusions and the Madness <strong>of</strong> Crowds, has left generations <strong>of</strong> readers convinced <strong>of</strong> the<br />

irrational greed behind Tulip Mania, the South Sea Bubble, and the Mississippi Scheme.<br />

This course takes these three early modern “bubbles” as case studies in market failure. In the<br />

first part <strong>of</strong> the course, we will investigate what, if any, market fundamentals drove investor<br />

behavior and will study the contemporary polemical literature which followed in the wake <strong>of</strong><br />

each speculative disaster. As an alternative approach, we will investigate the role <strong>of</strong> legal<br />

and regulatory regimes in increasing leverage and will explore the place <strong>of</strong> new<br />

11

technological and financial innovations as focal points <strong>of</strong> asset-price bubbles. By bringing<br />

new capital into markets, asset-price bubbles serve first to foster and then, by their collapse,<br />

to resolve what economists describe as the ‘lemons problem.’ Those who cannot tell good<br />

wine from bad will overpay for the latter but reject the former as commanding too high a<br />

price. Yet this is also how untested ideas attract financing. In Weeks 4, 5 and 6, students will<br />

learn about the development <strong>of</strong> international capital markets and their role in financing both<br />

state and private ventures. Students will decide for themselves what both behavioral finance<br />

and closely historicized studies <strong>of</strong> market microstructure can <strong>of</strong>fer historians <strong>of</strong> financial<br />

capitalism. Students will learn why modern financial and economic historians consider<br />

interpretations <strong>of</strong> asset-price bubbles pivotal to theoretical debates about rational and<br />

efficient markets. In the second half <strong>of</strong> the course, we will apply these models to three<br />

nineteenth and twentieth-century financial bubbles. Students will then develop their own<br />

research projects in which they interrogate the market realities behind a financial bubble <strong>of</strong><br />

their choosing.<br />

General Reading<br />

• Eichengreen, Barry. Globalizing Capital: A <strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> the International Monetary<br />

System (Princeton <strong>University</strong> Press, 2008).<br />

• Kindleberger, Charles. Manias, Panics and Crashes: A <strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> Financial Crisis.<br />

(John Wiley & Sons, 2000).<br />

• Michie, Ranald. The Global Securities Market (Oxford <strong>University</strong> Press, 2008)<br />

• Vogel, Harold. Financial Market Bubbles and Crashes (<strong>Cambridge</strong> <strong>University</strong> Press,<br />

2009).<br />

6) Language and society (a course taught by the MPhil in Early Modern <strong>History</strong>)<br />

Dr P Withington<br />

This course invites students to think about what words meant in early-modern Europe – not<br />

merely to social and intellectual elites (though they are certainly part <strong>of</strong> the mix) but also<br />

ordinary men and women. In so doing it encourages reflection about the implications <strong>of</strong><br />

these meanings – and their changes and continuities over time – for social attitudes,<br />

relationships, and practices. These aims reflect not only the impact <strong>of</strong> the infamous<br />

‘linguistic turn’ on early modern studies, but also that some <strong>of</strong> the most interesting recent<br />

work on language and meaning has been done at the intersection between literary,<br />

intellectual, and social history. To this end students will discuss the way historians have<br />

approached language and discourse over the past forty years and consider the cultural<br />

movements that transformed European vernaculars from the later fifteenth century. They<br />

will be introduced to the kinds <strong>of</strong> evidence available to historians and the possibilities <strong>of</strong><br />

interpretation. They will also think about particular words and vocabularies that have<br />

attracted especial historical attention. In the final week they will research a word <strong>of</strong> their<br />

own choice. The focus will be on English, though there will be opportunities for students to<br />

consider words in other vernaculars if they so wish. There will be a moderate amount <strong>of</strong><br />

preparation for each class, and students will be expected to give a short presentation over the<br />

course <strong>of</strong> the term. Assessment will be by an essay on one aspect <strong>of</strong> the course (title agreed<br />

with the tutor) and by evidence <strong>of</strong> satisfactory participation.<br />

Classes are likely to cover:<br />

• Approaches to language and society<br />

• Humanism and vernacularization<br />

• Sources and interpretation<br />

• Economic vocabularies<br />

• Political language<br />

• Language and social identity<br />

• Personal research<br />

Some Suggestions for Introductory Reading<br />

Robert M. Burns, ed., Historiography. Critical Concepts in Historical Studies (New York,<br />

2005), Part One.<br />

12

Reinhart Koselleck, The Practice <strong>of</strong> Conceptual <strong>History</strong> (Stanford, 2002)<br />

J. G. A. Pocock, ‘The Concept <strong>of</strong> Language and the Metier d’Historien: Some<br />

Considerations on Practice’ in Anthony Pagden, ed., The Language <strong>of</strong> Political Theory in<br />

Early Modern Europe (New York, 1985)<br />

Quentin Skinner, Visions <strong>of</strong> Politics: Volume I: Regarding Method (<strong>Cambridge</strong>, 2002), esp.<br />

chapters. 9 & 10<br />

Anna Wierzbicka, Understanding Cultures Through Their Key Words (Oxford, 1997)<br />

Raymond Williams, Keywords (Harmondsworth, 1976)<br />

Keith Wrightson, ‘Estates, Degrees and Sorts: Changing Perceptions <strong>of</strong> Society in Tudor and<br />

Stuart England’ in Penelope Corfield, ed., Language, <strong>History</strong> and Class (Oxford, Blackwell,<br />

1991)<br />

______, English Society, 1580–1680 (London, 1982)<br />

7) Gender and development<br />

Dr N Mora-Sitja<br />

This course will examine the literature, debate, and approaches linking gender, economic<br />

growth and historical development. Key questions will be how crucial the role <strong>of</strong> women has<br />

been for economic development, and how particular growth trajectories have impacted on<br />

women's status. In order to do so, the course will explore several theoretical and<br />

methodological approaches to the study <strong>of</strong> women and the economy, with particular<br />

emphasis on gender roles at work and within the family, as well as tools to measure and<br />

identify discrimination. The second half <strong>of</strong> the course will be devoted to a comparative study<br />

<strong>of</strong> the impact that key economic developments, such as industrialization or globalization,<br />

have had on gender outcomes, in order to establish more systematic connections between<br />

gender discrimination and the economy.<br />

Some Suggestions for Introductory Reading<br />

Boserup, E. (1970), Woman's Role in Economic Development, New York<br />

Momsen, J.H., Women and Development in the Third World (1991)<br />

Scott, J.W., Gender and the Politics <strong>of</strong> <strong>History</strong> (1988)<br />

Becker, G.S. (1981), A Treatise on the Family<br />

Goldin, C., Understanding the Gender Gap. An Economic <strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> American Women<br />

(1990).<br />

Hudson, P. and Lee, W.R. (1990), Women's Work and the Family Economy in Historical<br />

Perspective<br />

Lewis, J. (1984), Women in England, 1870-1950: Sexual Divisions and Social Change<br />

Marcia Guttentag and Paul F. Secord. Too Many Women The Sex Ratio Question.<br />

Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications, 1983.<br />

L. Gordon (ed.) Women, the State and Welfare (1990)<br />

D. Sainsbury (ed.) Gender and Welfare State Regimes (1999)<br />

Burnette, J., Gender, Work and wages in Industrial Revolution Britain (2009)<br />

8) The economic policies <strong>of</strong> right-wing dictatorships in the era <strong>of</strong> mass politics<br />

Dr C Ristuccia<br />

This course will analyse economic policy making by European right-wing dictatorships in<br />

the 20 th century, including Fascist Italy, Poland under Marshal Piłsudski, Portugal under<br />

Salazar, Nazi Germany, Franco’s Spain, and Vichy France. <strong>Course</strong> topics will include<br />

nationalism as an economic ideology, theories <strong>of</strong> citizenship in dictatorships, and the impact<br />

<strong>of</strong> economic superiority on the outcome <strong>of</strong> WW2, complemented with in-depth studies <strong>of</strong><br />

economic policy in the countries listed above. The course’s comparative framework, and its<br />

exploration <strong>of</strong> methodological and theoretical tools to study nationalist economic policies,<br />

should provide the students with a solid background to understand Europe’s twentieth<br />

century. Classes will be spread over Michaelmas and Lent.<br />

Introductory reading list<br />

Ben-Ghiat, R. (2001), Fascist Modernities: Italy, 1922–1945, Berkeley and Los Angeles,<br />

CA: <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> California Press.<br />

13

Bosworth, R. J. B. (1998), The Italian dictatorship. Problems and perspectives in the<br />

interpretation <strong>of</strong> Mussolini and fascism, London.<br />

Harrison, M. (ed.), The economics <strong>of</strong> World War II. Six great powers in international<br />

comparison, <strong>Cambridge</strong>: <strong>Cambridge</strong> <strong>University</strong> Press<br />

Jackson, J. (2001), France: The Dark Years, 1940–1944, Oxford: Oxford <strong>University</strong> Press.<br />

Kallis, A. A. (2000), Fascist Ideology: Territory and Expansionism in Fascist Italy and Nazi<br />

Germany, 1922–1945, London: Routledge.<br />

Knox, M. (2000), Common destiny: dictatorship, foreign policy, and war in fascist Italy and<br />

Nazi Germany, <strong>Cambridge</strong>: <strong>Cambridge</strong> <strong>University</strong> Press.<br />

Liberman, P. (1996), Does conquest pay The exploitation <strong>of</strong> occupied industrial societies,<br />

Princeton: Princeton <strong>University</strong> Press.<br />

Milward, A. S. (1987), War, economy and society, 1939-1945, Harmondsworth: Penguin<br />

Morgan, P. (2002), Fascism in Europe, 1919–1945, London: Routledge.<br />

Overy, R. J. (1996), Why the Allies won: explaining victory in World War II, London:<br />

Pimlico.<br />

Roberts, D. D. (2006), The Totalitarian Experiment in Twentieth-Century Europe:<br />

Understanding the Poverty <strong>of</strong> Great Politics.<br />

Rodogno, D. (2006), Fascism's European Empire: Italian Occupation during the Second<br />

World War, <strong>Cambridge</strong>: <strong>Cambridge</strong> <strong>University</strong> Press.<br />

Thomas, M. (1998), The French empire at war, 1940–1945, Manchester: Manchester<br />

<strong>University</strong> Press.<br />

Tooze, A. (2006), The Wages <strong>of</strong> Destruction: The Making and Breaking <strong>of</strong> the Nazi<br />

Economy, London: Allen Lane.<br />

Willson, P. R., The clockwork factory. Women and work in fascist Italy, Clarendon Press,<br />

Oxford 1993.<br />

2.5 Presentation and Submission <strong>of</strong> Essays and Dissertations<br />

Essays and the dissertation should be submitted to the MPhil Office on the prescribed dates,<br />

as follows:<br />

Part I: Two copies <strong>of</strong> each essay, stapled or s<strong>of</strong>t bound;<br />

Part II: Two bound copies <strong>of</strong> the dissertation and a labelled CD containing an<br />

electronic version <strong>of</strong> the dissertation (so that if necessary the word count<br />

may be independently verified). The dissertation may be spiral bound or in<br />

a plastic folder, but must be sufficiently secure as to be durable. If you<br />

wish to submit it with a more solid binding, there are good services run by<br />

the <strong>University</strong> Reprographics Centre (Old Schools) and the Graduate<br />

Students’ Union.<br />

Essays and dissertations must be typed on one side <strong>of</strong> A4 paper, one-and-a-half or doublespaced,<br />

in a typeface <strong>of</strong> 11 or 12 point font.<br />

• The title page <strong>of</strong> your dissertation should contain Title, Name, College, Date (optional)<br />

and Declaration stating 'This dissertation is submitted for the degree <strong>of</strong> Master <strong>of</strong><br />

Philosophy.'<br />

• There should be a declaration in the Preface stating: ‘This dissertation is the result <strong>of</strong><br />

my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome <strong>of</strong> work done in collaboration<br />

except where specifically indicated in the text’.<br />

• Please number the pages <strong>of</strong> the dissertation.<br />

• The dissertation must include a bibliography <strong>of</strong> all (and only) works cited.<br />

Important points in relation to the word limit:<br />

• The word count includes appendices and statistical tables at 150 words per table, but<br />

excludes footnotes, references and bibliography. No penalty will be imposed for an<br />

excess <strong>of</strong> 50 words (for an essay) or 150 (for a dissertation) over the maximum word<br />

limit, but this allowance should not be abused. The MPhil sub-committee acting as a<br />

Board <strong>of</strong> Examiners has the discretion to penalise essays/dissertations which exceed the<br />

14

word limit. The word limit (within the 50 / 150 words grace allowance) must<br />

therefore be strictly observed. Students can expect to be severely penalised for<br />

exceeding the word limit. Normally the penalty will be the deduction <strong>of</strong> up to 5 marks<br />

from the essay/dissertation, but in severe cases the work may be marked as failed.<br />

• Footnotes should be restricted to the documentation <strong>of</strong> claims and the registration <strong>of</strong><br />

relevant caveats or observations in relation to the literature. Footnotes must not be used<br />

to circumvent the word limit <strong>of</strong> the essay or dissertation. Students can expect to be<br />

severely penalised for abusing the proper use <strong>of</strong> footnotes in this way. Normally the<br />

penalty will be a deduction <strong>of</strong> up to 5 marks from the essay or dissertation, but in<br />

severe cases the essay or dissertation may be marked as failed.<br />

• The word count <strong>of</strong> the entire essay or dissertation (excluding footnotes), must be<br />

recorded on a separate page bound up with the essay or dissertation. An electronic copy<br />

<strong>of</strong> the dissertation on CD must also be provided so that if necessary the word count may<br />

be verified.<br />

2.6 Deadlines for Submission<br />

Submission dates must be strictly adhered to.<br />

If there are grave and convincing reasons why work for Part I assessment cannot be submitted<br />

on time, the Secretary <strong>of</strong> the MPhil must be informed <strong>of</strong> these in writing at the <strong>History</strong> <strong>Faculty</strong>, or<br />

by email, before the deadline. These reasons will normally be either medical, in which case a<br />

statement from a College nurse or a GP must also be provided, or personal, in which case a<br />

supporting letter from the student’s College tutor is also required. The Chair and/or Academic<br />

Secretary <strong>of</strong> the MPhil are able in these circumstances to consider granting an extension. An<br />

extension will normally only be considered for the actual amount <strong>of</strong> time lost, and students should<br />

be aware that excessive delay may make it impossible for their work to be examined at the same<br />

time as that <strong>of</strong> other students and may consequently delay receipt <strong>of</strong> their results.<br />

Whereas in the case <strong>of</strong> the essays, the Academic Secretary and Chair are able to grant extensions in<br />

compelling circumstances, in the case <strong>of</strong> the dissertation there is a formal procedure laid down<br />

by the Board <strong>of</strong> Graduate Studies by which extensions must be sought. These may only be<br />

granted where there are grave and convincing reasons for a delay in submission. These reasons will<br />

normally be either medical, in which case a statement from a College nurse or a GP must also be<br />

provided, or personal, in which case supporting comments from the students College tutor are also<br />

required. An extension should be applied for in advance, normally at least one week before the<br />

submission date, using the appropriate application form downloaded from your Self-Service pages in<br />

CamSIS: http://www.admin.cam.ac.uk/<strong>of</strong>fices/gradstud/current/submitting/deferring.html. After<br />

initial consideration by the MPhil Sub-Committee, the application will be referred to the next<br />

available Degree Committee meeting and, if approved, forwarded to the Board <strong>of</strong> Graduate Studies.<br />

Official confirmation that leave to defer has been granted will be sent to the student by the BGS. If<br />

in any doubt about this procedure, please contact the MPhil Office for advice.<br />

Mechanical breakdown in the functioning <strong>of</strong> word processors will not normally be regarded as a<br />

sufficient excuse for late submission. Students are therefore strongly advised to plan to complete<br />

their work a couple <strong>of</strong> days in advance <strong>of</strong> the deadlines in order to avoid such problems, and to back<br />

up their work regularly in multiple formats.<br />

15

APPENDIX A:<br />

LIST OF ACADEMIC STAFF ASSOCIATED WITH THE MPHIL<br />

Dr H-J Chang<br />

(Development Studies and<br />

Economics & Politics)<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor MJ Daunton<br />

(<strong>History</strong> & Trinity Hall)<br />

Dr S Fennell<br />

(Development Studies and<br />

Jesus)<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor MJ Hatcher<br />

(<strong>History</strong> & Corpus<br />

Christi)<br />

Role <strong>of</strong> the state in economic change; industrial policy and<br />

technology policy; privatisation and regulation; theories <strong>of</strong><br />

institutions and morality; the East Asian economies; corporate<br />

governance.<br />

Economic and Social history <strong>of</strong> Britain since 1700, especially<br />

economic and social policy, urbanisation, and globalisation<br />

since 1945. Author <strong>of</strong> Progress and Poverty: An economic and<br />

social history <strong>of</strong> Britain, 1700-1850 (1995), Trusting<br />

Leviathan: The Politics <strong>of</strong> Taxation in Britain, 1799-1914<br />

(2001), Just Taxes: The Politics <strong>of</strong> taxation in Britain, 1914-79<br />

(2002), and Wealth and welfare: An economic and social<br />

history <strong>of</strong> Britain, 1851-1951 (2007).<br />

Political institutions, household, community and development<br />

in twentieth-century China and India.<br />

Medieval and early modern British economic and social<br />

history. Recent publications include Modelling the Middle<br />

Ages: the history and theory <strong>of</strong> England’s economic<br />

development (OUP 2001), and Understanding the population<br />

history <strong>of</strong> England, 1450-1750, Past and Present (2003).<br />

Dr S Horrell (Economics) Labour market participation <strong>of</strong> women and children; household<br />

structure, standards <strong>of</strong> living and expenditure c1750-1900;<br />

structures <strong>of</strong> consumption and production in 19 th century<br />

Britain.<br />

Dr J Lawrence (<strong>History</strong><br />

& Emmanuel College)<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor P Mandler<br />

(<strong>History</strong> & Gonville and<br />

Caius)<br />

Dr J Marfany (<strong>History</strong><br />

& Homerton)<br />

Dr N Mora-Sitja (<strong>History</strong><br />

& Downing)<br />

Dr JC Muldrew (<strong>History</strong><br />

& Queens’)<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor E Rothschild<br />

(<strong>History</strong> & King’s)<br />

British social, political and cultural history from the mid<br />

nineteenth century to the present. Currently working on the<br />

history <strong>of</strong> class identity in Britain between the 1930s and the<br />

1990s.<br />

Cultural and social history <strong>of</strong> Britain since 1800; history <strong>of</strong> the<br />

social sciences in the 20 th century. Author <strong>of</strong> The Fall and<br />

Rise <strong>of</strong> the Stately Home (1997), <strong>History</strong> and National Life<br />

(2002); The English National Character (2006). Current work<br />

on ideas about modernization and globalization in 19 th and<br />

20 th -century Britain; the history <strong>of</strong> the idea <strong>of</strong> ‘national<br />

identity’; the place <strong>of</strong> social science in everyday life in 20 th -<br />

century Britain and America; the history <strong>of</strong> anthropology and<br />

‘cultural relativism’.<br />

Economic and social history <strong>of</strong> England and Europe,<br />

especially: eighteenth-century Spain, proto-industry,<br />

population growth, marriage and family formation, living<br />

standards, consumption and poverty and welfare.<br />

Modern European economic history, especially: Spanish<br />

history since 1750; labour markets and industrialisation; the<br />

standard <strong>of</strong> living; globalization and inequality.<br />

British early modern economic and social history.<br />

18th and 19th century French and English economic ideas.<br />

Author <strong>of</strong> Economic Sentiments: Adam Smith, Condorcet and<br />

the Enlightenment (HUP, 2001), 'Global Commerce and the<br />

Question <strong>of</strong> Sovereignty in the 18th Century Provinces' in<br />

16

Dr L Shaw-Taylor<br />

(<strong>History</strong>)<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor RM Smith<br />

(Geography & Downing)<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor SR Szreter<br />

(<strong>History</strong> & St John’s)<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor R P Tombs<br />

(<strong>History</strong> & St John’s<br />

College)<br />

Dr BC Wood (<strong>History</strong> &<br />

Girton)<br />

Modern Intellectual <strong>History</strong> (2004), 'Language and Empire,<br />

c.1800' in Historical Research (2005), 'A Horrible Tragedy in<br />

the French Atlantic' in Past and Present (2006).<br />

English economic and social history 1500-1850, especially:<br />

common rights, enclosure and proletarianisation; the standard<br />

<strong>of</strong> living; agricultural productivity; occupational structure and<br />

industrialisation. Author: ‘Labourers, cows, common rights<br />

and parliamentary enclosure: the evidence <strong>of</strong> contemporary<br />

comment c 1760-1810’, Past and Present (2001).<br />

‘Parliamentary Enclosure and the Emergence <strong>of</strong> an English<br />

Agricultural Proletariat’, Journal <strong>of</strong> Economic <strong>History</strong> (2001).<br />

De Moore, M., Shaw-Taylor, L., Warde, P., The Management<br />

<strong>of</strong> Common Land in North West Europe ca. 1500-1850 (2002).<br />

Medieval and early modern population and economic history.<br />

Author <strong>of</strong> (with Peter Laslett) Bastardy and its Comparative<br />

<strong>History</strong> (1980), Land,Kinship and Life-cycle (1984), with L.<br />

Bonfield and Keith Wrightson, The World We Have Gained<br />

(1986), with Margaret Pelling, Life, Death and the Elderly:<br />

Historical Perspectives (1991), with Zvi Razi, The Manor<br />

Court and English Society (1996).<br />

Demographic history, including the intellectual history <strong>of</strong> the<br />

field and contemporary policy questions. Author <strong>of</strong> Fertility,<br />

Class and Gender in Britain 1860-1940 (1996); Changing<br />

Family Size in England and Wales 1891-1911: place, class<br />

and demography (with E. Garrett, A. Reid and K. Schurer)<br />

(2001); Health and Wealth: studies in history and policy<br />

(2005); edited (with H. Sholamy, A. Dharmlingam),<br />

Categories and Contexts: Anthropological and Historical<br />

Studies in Critical Demography (2004); Sex Before the Sexual<br />

Revolution. Intimate Life in England 1918-1963 (with Kate<br />

Fisher) (2010).<br />

Modern French and European <strong>History</strong>, and Franco-British<br />

relations. Author <strong>of</strong> France 1814-1914 (1996), The Paris<br />

Commune 1871 (1999), co-author <strong>of</strong> That Sweet Enemy (2006)<br />

and co-editor <strong>of</strong> Cross-Channel Currents:100 Years <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Entente Cordiale (2004).<br />

Colonial American social history.<br />

Many other members <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Cambridge</strong> <strong>History</strong> <strong>Faculty</strong> may be available to supervise dissertations.<br />

17

APPENDIX B:<br />

MPHIL IN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL HISTORY – MARKING AND EXAMINATION<br />

SCHEME<br />

1. SUMMARY OF THE COURSE STRUCTURE<br />

Part I (40%)<br />

a. Central Concepts and Problems in Economic and Social <strong>History</strong> and Theory (10%)<br />

b. Research Methods <strong>Course</strong> (10%)<br />

Social Science Research Methods <strong>Course</strong> (6%)<br />

Dissertation Proposal Essay (4%)<br />

c. Two Advanced <strong>Course</strong>s in Economic and/or Social <strong>History</strong> chosen from a specified list <strong>of</strong><br />

subjects (10% each).<br />

Part II (60%)<br />

a. A dissertation <strong>of</strong> between 15,000 and 20,000 words (including appendices and statistical tables,<br />

but excluding footnotes, references and bibliography) to be submitted at the end <strong>of</strong> August.<br />

2. THE MARKING SCHEME<br />