Fall 2008: The State of our Seabirds - American Bird Conservancy

Fall 2008: The State of our Seabirds - American Bird Conservancy

Fall 2008: The State of our Seabirds - American Bird Conservancy

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

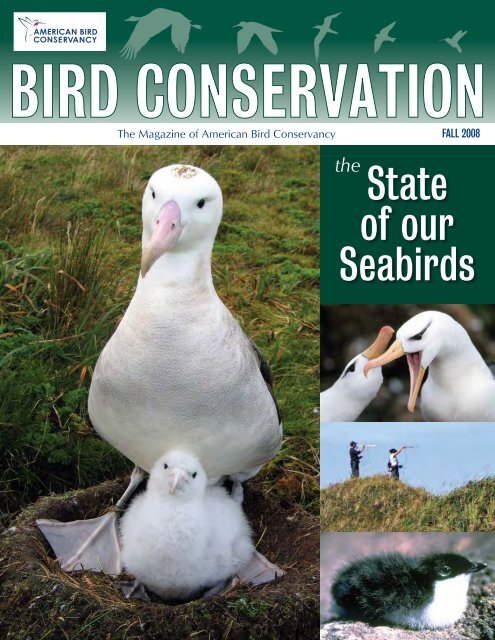

BIRD CONSERVATION<br />

<strong>The</strong> Magazine <strong>of</strong> <strong>American</strong> <strong>Bird</strong> <strong>Conservancy</strong> FALL <strong>2008</strong><br />

the<br />

<strong>State</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>our</strong><br />

<strong>Seabirds</strong>

BIRD’S EYE VIEW<br />

White-capped Albatross: P. Milburn<br />

By Carl Safina<br />

Albatrosses embody the wonders <strong>of</strong> Earth’s oceans. <strong>The</strong>se nomadic voyagers <strong>of</strong> the<br />

high seas rarely come within sight <strong>of</strong> land, and so, magnificent as they are, go<br />

virtually unnoticed by all but the fishermen and sailors (and the occasional highly<br />

motivated birdwatchers) who venture out beyond the protective embrace <strong>of</strong> <strong>our</strong> coastlines.<br />

As a result, their tragic decline has for decades gone widely unnoticed as well.<br />

As a result <strong>of</strong> past exploitation, introduced rodents, and drowning<br />

on fishing gear, certain albatrosses are teetering on the brink <strong>of</strong><br />

extinction. Nineteen out <strong>of</strong> the 22 albatross species are listed by<br />

IUCN-World Conservation Union as globally threatened (Critically<br />

Endangered, Endangered, or Vulnerable); the other three are<br />

considered Near Threatened. This is astonishing given that we are<br />

talking about an entire family <strong>of</strong> bird species whose distribution<br />

spans the planet. This is not some small set <strong>of</strong> endemic birds<br />

plagued by regional habitat loss or localized mortality threats.<br />

This is a matter <strong>of</strong> global scale.<br />

Thankfully though, the plight <strong>of</strong> the world’s seabirds is beginning<br />

to gain some attention. Groups such as <strong>American</strong> <strong>Bird</strong><br />

<strong>Conservancy</strong>, the Blue Ocean Institute, and many others, have<br />

raised awareness <strong>of</strong> albatross and other seabird declines, and as a<br />

consequence, there have been some improvements. For example,<br />

government-mandated regulations have resulted in a significant<br />

drop in the bycatch <strong>of</strong> seabirds by longline fishing vessels operating<br />

in waters <strong>of</strong>f Alaska, Hawaii, New Zealand, the Falklands, South<br />

Georgia Island, the Sub-Antarctic, and elsewhere. Islands that form<br />

the restricted breeding sites for some seabird species are beginning<br />

to be purged <strong>of</strong> the introduced predators such as rats and cats that<br />

have decimated populations in recent decades.<br />

While the United <strong>State</strong>s has demonstrated leadership on some<br />

fronts in the global effort to conserve threatened seabirds, we can<br />

do much more. Not least, but perhaps most simply, is to add <strong>our</strong><br />

signature to the Agreement on the Conservation <strong>of</strong> Albatrosses and<br />

Petrels. ACAP is the leading international agreement bringing<br />

countries together to reduce threats and ensure the future <strong>of</strong><br />

highly migratory albatross and petrel species. To date, 12 leading<br />

fishing nations—Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador,<br />

Uruguay, France, New Zealand, Peru, South Africa, Spain, and<br />

the United Kingdom—have signed ACAP. Far from ignoring this<br />

key accord, the United <strong>State</strong>s was a significant player in the negotiation<br />

<strong>of</strong> ACAP, and has since attended meetings as an observer.<br />

Yet it has fallen short <strong>of</strong> adding its signature and becoming a full<br />

party to the Agreement. Without this final commitment, the<br />

United <strong>State</strong>s cannot directly influence priority setting and policy<br />

to protect the 28 seabird species covered by ACAP.<br />

Given that America already implements all the Agreement’s provisions,<br />

signing ACAP would place no additional burden on us.<br />

Rather it would give us a seat at the table as opposed to <strong>our</strong> current<br />

perch outside the window, and present us with the chance to<br />

push <strong>our</strong> domestic agenda <strong>of</strong> seabird conservation internationally.<br />

It would also enable us to level the playing field for <strong>our</strong> fishermen,<br />

who must currently observe U.S. regulations that are far more<br />

stringent than the laws that govern the actions <strong>of</strong> many <strong>of</strong> their<br />

foreign competitors.<br />

President Bush must make it a priority to sign ACAP before he<br />

leaves <strong>of</strong>fice in January 2009. In 2007, he presided over the designation<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument<br />

that surrounds the Northwest Hawaiian Islands—nesting grounds<br />

to the largest albatross population in the world. <strong>The</strong> creation <strong>of</strong><br />

the single largest conservation area under the U.S. flag, and one<br />

<strong>of</strong> the largest marine conservation areas in the world, demonstrated<br />

a real commitment to marine protection. Now he must<br />

bring this commitment to the international arena, and send a<br />

clear signal to the rest <strong>of</strong> the world that seabird conservation is a<br />

global problem that demands collaborative global solutions.<br />

<strong>The</strong> fight to preserve the Arctic wilderness against the push for the<br />

extraction <strong>of</strong> its oil reserves has proven just how much people care<br />

about places that most will likely never visit. <strong>The</strong> struggle to prevent<br />

the mass extinction <strong>of</strong> <strong>our</strong> seldom seen albatrosses is going to<br />

take a similar investment on a global scale. <strong>The</strong> developing public<br />

interest in seabird conservation gives us hope that it is possible,<br />

and with the United <strong>State</strong>s fully on-board with ACAP, we can help<br />

make it happen.<br />

Carl Safina is the author <strong>of</strong> Eye <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Albatross and Song for the Blue Ocean,<br />

and is President and co-founder <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Blue Ocean Institute.<br />

Carl Safina and Waved Albatrosses:<br />

Blue Ocean Institute<br />

2 bird conservation • FALL <strong>2008</strong><br />

COVER PHOTOS: (Left) Wandering Albatross and chick: A. Angel and R. Wanless/VIREO;<br />

(Right, top to bottom) Black-browed Albatrosses: R. Saldino/VIREO; biologists tracking radio-tagged<br />

birds on Adak Island: Steve Ebbert/FWS; Xantus’s Murrelet chick: National Park Service.

<strong>Bird</strong> Conservation is the magazine <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Bird</strong> <strong>Conservancy</strong> (ABC), and<br />

is published three times yearly.<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Bird</strong> <strong>Conservancy</strong> (ABC) is the<br />

only 501(c)(3) organization that works<br />

solely to conserve native wild birds and<br />

their habitats throughout the Americas.<br />

A copy <strong>of</strong> the current financial statement<br />

and registration filed by the organization<br />

may be obtained by contacting: ABC, P.O.<br />

Box 249, <strong>The</strong> Plains, VA 20198. Tel: (540)<br />

253-5780, or by contacting the following<br />

state agencies:<br />

Sooty Albatross: Mike Danzenbaker<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>of</strong> Our <strong>Seabirds</strong><br />

7 <strong>The</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>of</strong> Our <strong>Seabirds</strong><br />

10 Toothfish Revisited<br />

<strong>Bird</strong>Conservation<br />

FALL <strong>2008</strong><br />

PAGE 7<br />

Tristan Albatross and chick: Angel Wanless<br />

Florida: Division <strong>of</strong> Consumer Services,<br />

toll-free number within the <strong>State</strong>:<br />

800-435-7352.<br />

Maryland: For the cost <strong>of</strong> copies and<br />

postage: Office <strong>of</strong> the Secretary <strong>of</strong> <strong>State</strong>,<br />

<strong>State</strong>house, Annapolis, MD 21401.<br />

New Jersey: Attorney General, <strong>State</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> New Jersey: 201-504-6259.<br />

New York: Office <strong>of</strong> the Attorney General,<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Law, Charities Bureau,<br />

120 Broadway, New York, NY 10271.<br />

Pennsylvania: Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>State</strong>,<br />

toll-free number within the state:<br />

800-732-0999.<br />

Virginia: <strong>State</strong> Division <strong>of</strong> Consumer<br />

Affairs, Dept. <strong>of</strong> Agriculture and Consumer<br />

Services, P.O. Box 1163, Richmond, VA<br />

23209.<br />

West Virginia: Secretary <strong>of</strong> <strong>State</strong>, <strong>State</strong><br />

Capitol, Charleston, WV 25305.<br />

11 Gillnets<br />

13 Islands: No Guarantee <strong>of</strong> Safe Haven<br />

18 Saving the Waved Albatross<br />

21 Marine Contaminants<br />

PAGE 21<br />

PAGE 10<br />

Photo: Mike Parr<br />

PAGE 18<br />

Registration does not imply endorsement,<br />

approval, or recommendation by any state.<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Bird</strong> <strong>Conservancy</strong> is not<br />

responsible for unsolicited manuscripts<br />

or photographs. Approval is required<br />

for reproduction <strong>of</strong> any photographs or<br />

artwork.<br />

Victims <strong>of</strong> an oil spill: FWS.<br />

PAGE 6<br />

DEPARTMENTS<br />

Waved Albatross: Hara Woltz<br />

Editors:<br />

Jessica Hardesty, Steve Holmer,<br />

Michael J. Parr, David Pashley,<br />

Gemma Radko, Gavin Shire,<br />

George E. Wallace.<br />

For information contact:<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Bird</strong> <strong>Conservancy</strong><br />

4249 Loudoun Avenue<br />

P.O. Box 249<br />

<strong>The</strong> Plains, VA 20198<br />

Creating handicrafts for sale:<br />

Fundación ProAves,<br />

www.proaves.org<br />

2 <strong>Bird</strong>’s Eye View<br />

4 On <strong>The</strong> Wire<br />

24 Species Pr<strong>of</strong>ile<br />

Peruvian Tern<br />

Peruvian Tern chick: Patricia Saravia<br />

PAGE 24<br />

ABC’s <strong>Bird</strong> Conservation magazine brings you the best in bird conservation news and features. For more information on<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Bird</strong> <strong>Conservancy</strong>, please visit <strong>our</strong> website at www.abcbirds.org or call 1-888-BIRD-MAG.<br />

bird conservation • FALL <strong>2008</strong><br />

3

ON THE WIRE<br />

Hawaiian Petrel: Jack Jeffrey<br />

Pilot Hi-Tech Study Searches for Rare Hawaiian <strong>Bird</strong>s<br />

Detecting rare Hawaiian birds<br />

using conventional methods<br />

is difficult due to the rough,<br />

mountainous terrain, dense<br />

vegetation, and remote locations <strong>of</strong><br />

intact Hawaiian rainforests. ABC<br />

and the Conservation Endowment<br />

Fund <strong>of</strong> the Association <strong>of</strong> Zoos<br />

and Aquariums are supporting<br />

Hawaiian partners on the island <strong>of</strong><br />

Kauai in a pilot study to determine<br />

the feasibility <strong>of</strong> using Autonomous<br />

Recording Units (ARUs) to detect<br />

rare bird species. ARUs are small,<br />

battery-powered recording devices<br />

containing a microphone, s<strong>of</strong>tware,<br />

and built-in disk drive that turn<br />

on automatically to record bird<br />

calls. <strong>The</strong> devices are very low-<br />

maintenance, can sit unattended<br />

for weeks or even months, and<br />

collect up to 80 gigabytes <strong>of</strong> digital<br />

recordings.<br />

Although ARUs are a relatively new<br />

technology, they have already been<br />

successfully used to monitor Golden-cheeked<br />

Warblers and Blackcapped<br />

Vireos at Fort Hood, Texas,<br />

in areas where military exercises<br />

would pose a threat to researchers.<br />

ARUs are also being deployed in Arkansas<br />

to search for the Ivory-billed<br />

Woodpecker.<br />

Two ARUs have been leased from<br />

the Cornell Lab <strong>of</strong> Ornithology, and<br />

are being field tested by the Kauai<br />

Endangered Forest <strong>Bird</strong> Recovery<br />

Project and the Kauai Endangered<br />

Seabird Recovery Project. <strong>The</strong> study<br />

is being funded and directed by<br />

the Hawaii Division <strong>of</strong> Forestry and<br />

Wildlife. ARUs have been deployed<br />

in f<strong>our</strong> different areas on Kauai in an<br />

attempt to detect f<strong>our</strong> species: the<br />

Hawaiian Petrel, Newell’s Shearwater,<br />

Band-rumped Storm-Petrel, and<br />

Puaiohi (Small Kauai Thrush).<br />

Because <strong>of</strong> the difficulty <strong>of</strong> accessing<br />

some research locations on<br />

Kauai, use <strong>of</strong> ARUs could save thousands<br />

<strong>of</strong> dollars in helicopter transport<br />

charges and study time. ARUs<br />

will also help in better understanding<br />

the singing and calling behavior<br />

<strong>of</strong> Hawaiian landbirds, allowing<br />

researchers to fine-tune monitoring<br />

protocols to increase native bird<br />

detection success. ARUs could<br />

also help detect cryptic species—<br />

perhaps even species that have not<br />

been reported for years.<br />

Once the field portion <strong>of</strong> the study<br />

ends in August <strong>2008</strong>, the ARUs will<br />

be sent back to Cornell, where the<br />

data will be analyzed and the quality<br />

<strong>of</strong> the sound evaluated. “ARUs have<br />

tremendous promise for monitoring<br />

rare Hawaiian species while saving<br />

time and money in areas with very<br />

challenging logistics,” said George<br />

Wallace, ABC’s Vice President for<br />

International Programs. “We eagerly<br />

await the results <strong>of</strong> the pilot study.”<br />

ABC Campaigns for Green Building Standards to Save <strong>Bird</strong>s<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Bird</strong> <strong>Conservancy</strong> is<br />

advocating for green building<br />

standards to include<br />

provisions that reduce bird<br />

collisions.<br />

ABC, the <strong>Bird</strong>-Safe Glass Foundation,<br />

New York City Audubon, and<br />

architect Hillary Brown recently met<br />

with the U.S. Green Building Council<br />

to discuss changes to the LEED<br />

standards. LEED (Leadership in<br />

Energy and Environmental Design)<br />

is the most widely accepted benchmark<br />

for environmentally-friendly<br />

buildings, but does not currently take<br />

bird collisions into account. In June,<br />

this coalition submitted suggested<br />

changes to the proposed LEED2009<br />

standards. <strong>The</strong>se changes were<br />

endorsed by the Chicago Audubon<br />

Society, Chicago <strong>Bird</strong> Collision Monitors,<br />

<strong>Bird</strong>s and Buildings Forum,<br />

Fatal Light Awareness Program<br />

(FLAP), and collisions expert Dr.<br />

Daniel Klem, Jr.<br />

ABC also submitted comments to<br />

suggest bird-safe changes to the<br />

Green Building Initiative’s proposed<br />

<strong>American</strong> National Standard for<br />

Green Building. A similar group <strong>of</strong><br />

bird-safe building advocates signed<br />

on to support these comments.<br />

According to Dr. Klem, some 975<br />

million birds die every year from<br />

building collisions in the United<br />

<strong>State</strong>s alone. At night, migrating<br />

birds are attracted to, and disoriented<br />

by, the light emanating from<br />

the interiors <strong>of</strong> tall buildings and the<br />

outside vanity lighting and floodlights<br />

on buildings <strong>of</strong> any height. Trapped<br />

in these “light fields” and unable to<br />

view the stars by which they navigate,<br />

the birds fly in circles<br />

until they collide with each<br />

other or the building, or<br />

fall to the ground from<br />

exhaustion. <strong>The</strong> problem is<br />

particularly acute on nights<br />

with abundant low-altitude<br />

cloud cover or inclement<br />

weather. During the day,<br />

birds are at risk from collisions<br />

with reflective and<br />

transparent windows,<br />

which they cannot see.<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the unintended<br />

consequences <strong>of</strong> green<br />

building certification programs<br />

has been the promotion <strong>of</strong> large<br />

expanses <strong>of</strong> glass that increase<br />

daylight and reduce the need for<br />

artificial daytime lighting. This saves<br />

energy, but increases the danger<br />

<strong>of</strong> bird collisions. However, there<br />

are examples <strong>of</strong> high-performance<br />

green buildings that are also bird<br />

safe because they incorporate<br />

additional architectural elements.<br />

For example, the New York Times<br />

Building is covered by a network<br />

<strong>of</strong> exterior ceramic rods, which<br />

create enough “visual noise” to warn<br />

birds away from the windows, yet<br />

still allow daylight to the reach the<br />

building’s occupants.<br />

ABC’s goal is to integrate bird safety<br />

into the definition <strong>of</strong> a green building,<br />

and to have this reflected in specific<br />

performance standards to reduce<br />

collision hazards. Such standards<br />

will enc<strong>our</strong>age innovative designs<br />

by architects, and stimulate marketdriven<br />

solutions to the problem by<br />

increasing demand for new products,<br />

such as glass that is visible to<br />

birds but not to people—perhaps<br />

the ultimate high-tech solution to<br />

bird collisions with windows.<br />

It is clear that the debate should<br />

no longer be whether birds require<br />

these protections, but rather what<br />

are the most effective ways to design<br />

and operate buildings to prevent<br />

bird deaths. ABC will continue<br />

to work for bird-friendly buildings<br />

so they become the norm rather<br />

than the exception.<br />

A building in Toronto that has a variety <strong>of</strong><br />

collision deterrent films and netting in place<br />

to prevent bird collisions. Photo c<strong>our</strong>tesy <strong>of</strong><br />

FLAP (Fatal Light Awareness Program)<br />

4 bird conservation • FALL <strong>2008</strong>

ABC Report Finds Many Species <strong>of</strong> Migratory <strong>Bird</strong>s in Decline<br />

Act for Songbirds Campaign Underway to Boost Conservation<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Bird</strong> <strong>Conservancy</strong> has released a<br />

report revealing how the threats faced by<br />

Neotropical migratory birds are impacting their<br />

populations. Habitat loss and fragmentation<br />

are the greatest threats, but other hazards contribute<br />

towards population declines, including pesticide poisoning,<br />

collisions with buildings and communications<br />

towers, cat predation, invasive species, and global<br />

warming.<br />

<strong>The</strong> report, Saving Migratory <strong>Bird</strong>s for Future<br />

Generations: <strong>The</strong> Success <strong>of</strong> the Neotropical Migratory<br />

<strong>Bird</strong> Conservation Act, reveals a disturbing trend:<br />

nearly half <strong>of</strong> the species for which we have information<br />

are in long-term decline. Of the 178 continental bird<br />

species included on the <strong>American</strong> <strong>Bird</strong> <strong>Conservancy</strong>/<br />

Audubon WatchList <strong>of</strong> birds <strong>of</strong> highest conservation<br />

concern, over one-third –71 species – are Neotropical<br />

migrants. Two studies referenced in the report show<br />

that between 118 and 127 Neotropical migrant species have experienced<br />

persistent population declines over the last 40 years, including 60 species<br />

with declines <strong>of</strong> 45% or more.<br />

Fortunately, the report also finds that carefully targeted conservation efforts,<br />

such as projects supported by the Neotropical Migratory <strong>Bird</strong> Conservation<br />

Act (NMBCA), can help turn the tide for declining species.<br />

Representatives Ron Kind (D-WI) and Wayne Gilchrest<br />

(R-MD) have introduced legislation in the House (H.R.<br />

5756) to reauthorize NMBCA at a significantly higher<br />

funding level to help conservationists build on past and<br />

current successes. <strong>The</strong>se include establishing a network<br />

<strong>of</strong> monitoring stations and bird reserves in Colombia,<br />

restoring dwindling oak habitats for birds from Guatemala<br />

to Washington <strong>State</strong>, and protecting threatened<br />

stopover habitat in the Gulf <strong>of</strong> Mexico.<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Bird</strong> <strong>Conservancy</strong> has launched the Act for<br />

Songbirds Campaign to support this reauthorization<br />

bid, and is enc<strong>our</strong>aging citizens to take part by contacting<br />

their Representatives through ABC’s newly created<br />

online action center. Already, the Campaign has generated<br />

more than 4,000 letters to members <strong>of</strong> Congress<br />

in support <strong>of</strong> reauthorizing the Act. Organizations in the<br />

<strong>Bird</strong> Conservation Alliance, a broad network <strong>of</strong> ornithological societies,<br />

bird clubs, science, and conservation groups, are also working as part <strong>of</strong><br />

the campaign to engage their members in supporting the legislation.<br />

If you have not already taken action in support <strong>of</strong> the NMBCA reauthorization,<br />

please do so. It is the one simple thing that we can all do to help <strong>our</strong> migratory<br />

songbirds. Visit www.abcbirds.org/action to Act for Songbirds today.<br />

Western Bluebird Reintroduction<br />

–Second Year Successes<br />

An ABC partnership project to return Western Bluebirds to one <strong>of</strong> their<br />

ancestral breeding territories on the San Juan Islands <strong>of</strong> northwestern<br />

Washington <strong>State</strong> is nearing completion <strong>of</strong> the second year <strong>of</strong> its fiveyear<br />

timeline, with a number <strong>of</strong> important advances.<br />

<strong>The</strong> project got underway in the fall <strong>of</strong> 2006 (see <strong>Bird</strong> Conservation,<br />

Spring 2007), with support from the Disney Wildlife Conservation Fund, in<br />

collaboration with the San Juan Preservation Trust, Ecostudies Institute, and<br />

San Juan Islands Audubon Society, plus many other local partners.<br />

This year marked the first time in at least 40 years that a Western Bluebird<br />

that fledged on San Juan Island is known to have returned there to breed.<br />

<strong>The</strong> bird successfully paired and nested, providing an enc<strong>our</strong>aging early<br />

indication <strong>of</strong> potential long-term success. <strong>The</strong> first translocation <strong>of</strong> Western<br />

Bluebird pairs with nestlings was also accomplished. Two pairs were taken<br />

from their breeding site 100 miles away at Fort Lewis Military Installation<br />

in Olympia, Washington, and placed in an aviary on San Juan for ten days<br />

while their young fledged. <strong>The</strong> adults and eight fledglings were subsequently<br />

released successfully.<br />

Including these eight chicks, 21 bluebirds have fledged so far this year on<br />

San Juan, and f<strong>our</strong> pairs are re-nesting, making up for an unseasonably cold<br />

start to the season that resulted in the complete loss <strong>of</strong> one nest with five<br />

young, and the loss <strong>of</strong> three young from another brood <strong>of</strong> f<strong>our</strong>.<br />

Project coordinator Bob Altman, ABC’s Northern Pacific Rainforest <strong>Bird</strong><br />

Conservation Region Coordinator, commented: “Despite some nest losses<br />

due to record-setting cold weather, we were able to save several nests, and<br />

now with some pairs re-nesting, we hope to be able to successfully fledge<br />

approximately 30 young on San Juan Island this year.”<br />

Project partners and arriving Western Bluebirds (adults in cage and nestlings in covered bowl) at the<br />

Cady Mountain release site. Left to right are: Bob Altman, Kathleen Foley, Nicole McAllister, Gary Slater,<br />

and Eliza Habegger. Photo: Shaun Hubbard.<br />

Banding <strong>of</strong> an approximately 10-day-old Western<br />

Bluebird nestling from Uhlir’s farm, San Juan<br />

Island, WA. Photo: Kathleen Foley.<br />

Western Bluebird aviary amid large oak trees<br />

on Cady Mountain, San Juan Island, WA. Photo:<br />

Bob Altman.<br />

bird conservation • FALL <strong>2008</strong> 5

Women in Conservation Initiative<br />

Assists Colombian Communities<br />

Colombian partner, Fundación ProAves, is expanding<br />

its successful pilot program, Women in Conservation,<br />

to help protect six <strong>of</strong> its bird reserves by promoting<br />

business opportunities for women living in the nearby rural communities.<br />

Many <strong>of</strong> the local communities present a challenge to reserve management<br />

because they <strong>of</strong>ten cut forests to create food plots or for lumber to sell, and<br />

hunt wildlife. Women in particular lack job opportunities, and <strong>of</strong>ten have to<br />

resort to illegal poaching or wood-cutting to provide food for their families.<br />

A successful pilot program, begun by ProAves in 2004, trained women from<br />

f<strong>our</strong> villages to use natural, non-threatened res<strong>our</strong>ces to create handicrafts<br />

such as macramé, hand-painted objects, and embroidered bracelets and<br />

bookmarks. ProAves sells the finished products at shops on their reserves,<br />

and at events, exhibitions, and ornithological meetings worldwide. <strong>The</strong> money<br />

goes directly to the community, generating both income and a positive attitude<br />

towards the reserves among the local community. ProAves also employs local<br />

men as forest guards and guides, field assistants, and to help with reforestation<br />

activities, further benefiting the community, and designs environmental<br />

education programs to involve local children in conservation efforts.<br />

With ABC’s support, ProAves is now expanding the program to other<br />

communities (see map), helping to alleviate pressure on the reserves’<br />

protected res<strong>our</strong>ces. For more information, contact Sara Lara, Executive<br />

Director, Fundación ProAves, www.proaves.org.<br />

ProAves Reserves<br />

Photos by Fundación ProAves, www.proaves.org<br />

Laysan Albatross chick: Mary Hughes<br />

As you will read in this issue <strong>of</strong> <strong>Bird</strong> Conservation<br />

magazine, the threats to some <strong>of</strong><br />

the world’s most beautiful seabirds have<br />

reached critical proportions, to the point<br />

where 19 out <strong>of</strong> 22 species <strong>of</strong> albatross, as well<br />

as several species <strong>of</strong> petrels and alcids, are now<br />

threatened with extinction.<br />

But solutions are possible, and ABC has already<br />

had tremendous success in getting some<br />

implemented, with dramatic results. <strong>The</strong>re is<br />

much more to be done to alleviate the threat<br />

<strong>of</strong> gillnets, longlines, pollution, and introduced<br />

species, and you can help.<br />

Support ABC’s Seabird Program and help us<br />

safeguard key seabird nesting islands, work<br />

with regulators to reduce fisheries impacts, and<br />

collaborate with partners to find new solutions to<br />

existing threats.<br />

Send in y<strong>our</strong> special donation today using the<br />

enclosed envelope, and we will put it to the best<br />

use possible to ensure that albatrosses and the<br />

other magnificent seabirds are protected for<br />

future generations.<br />

Thank you,<br />

6 bird conservation • <strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2008</strong>

<strong>The</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

OUR SEABIRDS<br />

Laysan (left) and Black-footed (right) Albatrosses nest side-by-side on Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge: Mary Hughes.<br />

In 2002, <strong>American</strong> <strong>Bird</strong> <strong>Conservancy</strong> produced the<br />

report, Sudden Death on the High Seas: Longline Fishing,<br />

a Global Catastrophe. <strong>The</strong> report detailed the tremendous<br />

impact that longlining was having on albatross<br />

and some other seabird populations, and outlined simple,<br />

proven measures that could help reverse the situation. For<br />

this magazine, we take a look at longline fishing today<br />

to see how things have changed in the six years since <strong>our</strong><br />

report, and what progress has been made.<br />

<strong>Seabirds</strong> and fishermen are both after the same thing –<br />

fish – so wherever you find fishing boats on the open ocean,<br />

albatrosses, petrels, and other “pelagic” seabirds (those that<br />

spend most <strong>of</strong> their lives far out to sea) are never far away.<br />

<strong>The</strong> birds congregate around a boat and wait patiently. At<br />

some point, fish, squid, and other enticing fare will drop<br />

from the stern into the water, and for a moment will float<br />

tantalizingly on the surface. For the birds, it’s a bonanza<br />

<strong>of</strong> free food that they can’t resist. What they don’t know,<br />

however, is that each morsel is actually bait that is pierced<br />

through with a large metal hook attached to a longline that<br />

can be many miles in length. <strong>The</strong> easy meal quickly turns<br />

into a death sentence for any bird unfortunate enough to<br />

take the bait. <strong>The</strong> bird is impaled by the hook and dragged<br />

under to drown. So why don’t the birds learn that the free<br />

fish is a death trap Fishermen also dispose <strong>of</strong> fish waste<br />

(<strong>of</strong>fal) over the sides <strong>of</strong> their boats, and this food carries<br />

no fatal consequences. For the birds, it’s a game <strong>of</strong> Russian<br />

roulette.<br />

Longline fishing has been responsible for disastrous declines<br />

in populations <strong>of</strong> seabirds around the world over the last<br />

30 years or so, and this continues today. Largely because<br />

<strong>of</strong> longlining, 18 out <strong>of</strong> 22 species <strong>of</strong> albatrosses are now<br />

considered threatened with extinction (Vulnerable, Endangered,<br />

or Critically Endangered) under IUCN-World<br />

Conservation Union criteria. This is up from 16* in 2002.<br />

F<strong>our</strong>teen are considered to be declining, two have unknown<br />

trends, and five are “stable”, which leaves just one albatross<br />

species in the world, the federally endangered Short-tailed<br />

Albatross, that is considered to be increasing.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re have, however, been some improvements in the last<br />

six years, most notably in the United <strong>State</strong>s. In <strong>our</strong> 2002<br />

report, ABC noted the high number <strong>of</strong> seabirds that were<br />

being killed in the Alaskan and Hawaiian longline fisheries.<br />

An estimated 20,000 seabirds were killed each year in<br />

bird conservation • FALL <strong>2008</strong><br />

7

Black-browed Albatross: ClipArt.com<br />

Black-footed Albatross: ClipArt.com<br />

Shy Albatross: Mike Double<br />

Change in IUCN Red List Status <strong>of</strong> Albatross Species, 2002-<strong>2008</strong><br />

Species Status <strong>2008</strong> Status 2002 Trend <strong>2008</strong><br />

Amsterdam Albatross CR CR Declining<br />

Antipodean Albatross VU VU Unknown<br />

Atlantic Yellow-nosed Albatross EN NT Declining<br />

Black-browed Albatross EN VU Declining<br />

Black-footed Albatross EN VU Declining<br />

Buller’s Albatross VU VU Stable<br />

Campbell Albatross VU VU Stable<br />

Chatham Albatross CR CR Stable<br />

Grey-headed Albatross VU VU Declining<br />

Indian Yellow-nosed Albatross EN VU Declining<br />

Laysan Albatross VU LC Declining<br />

Light-mantled Albatross NT NT Declining<br />

Northern Royal Albatross EN EN Declining<br />

Salvin’s Albatross VU VU Stable<br />

Short-tailed Albatross VU VU Increasing<br />

Shy Albatross NT NT Unknown<br />

Sooty Albatross EN VU Declining<br />

Southern Royal Albatross VU VU Stable<br />

Tristan Albatross EN EN Declining<br />

Wandering Albatross VU VU Declining<br />

Waved Albatross CR VU Declining<br />

White-capped Albatross NT<br />

* Declining<br />

Red indicates a negative change in status from 2002 to <strong>2008</strong>.<br />

Wandering Albatross: Mark Jobling/wikipedia.com<br />

*White-capped and Shy Albatrosses were formerly considered the same species but later split, so the total<br />

number <strong>of</strong> albatross species has increased from 21 to 22.<br />

Alaskan waters, including Black-footed, Laysan, and Shorttailed<br />

Albatrosses. On average 1,051 albatrosses were caught<br />

each year between 1993 and 2000 in that fishery. Similar<br />

figures were reported in Hawaiian waters, which averaged<br />

2,377 albatrosses killed each year in 1999 and 2000.<br />

Today the picture looks very different. In 2006, only 88<br />

albatrosses (15 Laysan and 73 Black-footed) were killed <strong>of</strong>f<br />

the Hawaiian Islands, and 291 (57 Laysan and 134 Blackfooted)<br />

<strong>of</strong>f Alaska. Between 2002 and 2006, the average<br />

annual albatross toll decreased to 185 and 136 for Alaska<br />

and Hawaii respectively—a reduction <strong>of</strong> 82% for Alaska<br />

and 94% for Hawaii; this despite a near doubling <strong>of</strong> the<br />

number <strong>of</strong> hooks set in Hawaii.<br />

<strong>The</strong> reason behind these dramatic bycatch decreases is the<br />

mitigation measures that ABC advocated for, and that it<br />

promoted in its 2002 seabird report. <strong>The</strong> pressure from<br />

ABC and other groups paid <strong>of</strong>f, and in 2004, the federal<br />

government required all U.S. longline vessels over 55 feet<br />

long fishing in Alaskan waters to use paired streamer lines<br />

that keep birds away from baited hooks. Smaller vessels<br />

must use at least a single streamer line. In anticipation <strong>of</strong><br />

the regulations, many boats began voluntarily using the<br />

streamers ahead <strong>of</strong> the mandatory deadline, and immediately,<br />

their benefit was felt. <strong>The</strong> government complimented<br />

these regulations with a streamer line giveaway program<br />

that has so far provided more than 5,000 free lines. Cumulatively,<br />

these lines alone have been credited with reducing<br />

overall seabird bycatch in Alaska by nearly 70%.<br />

In Hawaii, albatrosses received a reprieve when the swordfish<br />

fishery was closed in 2000 due to excessive bycatch <strong>of</strong><br />

turtles. <strong>The</strong> fishery was reopened in 2004, but, along with<br />

all other Hawaiian longline fisheries, now mandates strict<br />

mitigation measures for the avoidance <strong>of</strong> seabird bycatch,<br />

<strong>The</strong> reason behind these dramatic bycatch decreases is<br />

the mitigation measures that ABC advocated for, and that<br />

it promoted in its 2002 seabird report.<br />

8 bird conservation • FALL <strong>2008</strong><br />

Tori lines, set beside longlines, scare seabirds away from baited<br />

hooks and prevent millions <strong>of</strong> albatross deaths. Photo: Liz Mitchell.

…tenuous as the future <strong>of</strong> all albatross species remains<br />

today, the reduction in the international threat <strong>of</strong><br />

longlining over the last six years has certainly benefited<br />

albatross species worldwide.<br />

Laysan Albatross: Glen Tepke<br />

that can include nighttime-only line setting, setting lines<br />

<strong>of</strong>f the side <strong>of</strong> the boat instead <strong>of</strong> the stern, use <strong>of</strong> devices<br />

called line shooters that keep bait away from the surface<br />

and out <strong>of</strong> reach <strong>of</strong> seabirds, and rules on how fish <strong>of</strong>fal is<br />

discharged.<br />

Internationally, there have been advances in the last six<br />

years too. Since 1990, the Commission on the Conservation<br />

<strong>of</strong> Antarctic Marine Living Res<strong>our</strong>ces (CCAMLR–one<br />

<strong>of</strong> many Regional Fisheries Management Organizations<br />

that bring together fishing nations to set fishery policy)<br />

has mandated strict avoidance measures in waters under its<br />

jurisdiction, which includes the ranges <strong>of</strong> the Wandering,<br />

Black-browed, and Grey-headed albatrosses, among others.<br />

Vessels must set lines at night when many birds are less<br />

active, must use a streamer line, and are prohibited from<br />

discharging <strong>of</strong>fal when lines are being set. <strong>The</strong>se rules have<br />

been so successful that in both 2005 and 2006, the Commission<br />

reported no known albatross deaths in its waters.<br />

CCAMLR has more power than other Fisheries Management<br />

Organizations, because Antarctica is administered by<br />

a treaty with specific regulations, but there has also been<br />

progress in some <strong>of</strong> the others.<br />

Estimated Albatross Bycatch for the<br />

Hawaii Longline Fleet, 1999-2006<br />

to pressure from large fishing fleets. Nearly half <strong>of</strong> the 22<br />

albatross species have at least part <strong>of</strong> their ranges within<br />

WCPFC waters, making this a significant development.<br />

Despite these successes, there are other international fisheries<br />

and Regional Fisheries Management Organizations<br />

spanning vast areas <strong>of</strong> ocean that still do not mandate<br />

comprehensive bycatch mitigation restrictions. Some do<br />

not even collect data, so that we simply do not know the<br />

extent <strong>of</strong> the bycatch problem. <strong>The</strong> United <strong>State</strong>s continues<br />

to import fish caught in these fisheries, thus indirectly contributing<br />

to the problem. In addition, illegal, unreported,<br />

and unregulated (IUU) fishing continues in many fisheries,<br />

by so-called “pirate” vessels that fish without any form <strong>of</strong><br />

seabird mitigation measures, further exacerbating the problem<br />

(see article on page 10 on Patagonian toothfish).<br />

Albatrosses are long-lived birds with slow reproductive<br />

rates, and so there has been insufficient time to see whether<br />

the progress that has been made translates into tangible<br />

population increases. As you will read elsewhere in this<br />

magazine, there are also other threats to albatrosses that<br />

have yet to be addressed. Nevertheless, tenuous as the<br />

future <strong>of</strong> all albatross species remains today, the reduction<br />

in the international threat <strong>of</strong> longlining over the last six<br />

years has certainly benefited albatross species worldwide.<br />

<strong>The</strong>ir long-term prospects will continue to improve the<br />

more broadly changes to international fishing practices are<br />

implemented and enforced.<br />

Black-footed Albatrosses ClipArt.com<br />

S<strong>our</strong>ce: NMFS PIRO<br />

In late 2006, the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries<br />

Commission (WCPFC) , which was established in 2004,<br />

set similar restrictions to limit seabird deaths, although<br />

introduction <strong>of</strong> these rules will be phased in gradually due<br />

Estimated Albatross Bycatch for the<br />

Alaska Longline Fleet, 1993-2006<br />

Laysan Albatross caught on a baited hook: NOAA.<br />

bird conservation • FALL <strong>2008</strong><br />

9

Chilean sea bass: wikipedia.com<br />

Toothfish Revisited<br />

Where restaurants are concerned, I am not usually a<br />

difficult customer. A pleasant smile to a waitress<br />

goes a long way, I have found; but there is nothing<br />

to change my demeanor from sweet to s<strong>our</strong> quicker than<br />

seeing Chilean sea bass on a menu. More properly called<br />

Patagonian toothfish, this prehistoric-looking species became<br />

a restaurant favorite because <strong>of</strong> its delicate flavor and<br />

highly forgiving oily flesh that stays tender even after being<br />

frozen, overcooked, and left sitting under a warming lamp<br />

for 15 minutes. Although relatively inexpensive to buy, the<br />

price to be paid for eating this fish must be calculated in<br />

more than just dollars and cents.<br />

Back <strong>The</strong>n<br />

What restaurant patrons did not know back in the 80s and<br />

90s, when the fish was at its most popular, is that overfishing<br />

<strong>of</strong> toothfish had caused severe population declines,<br />

to the extent that many stocks had reached the point <strong>of</strong><br />

collapse. Strict limits were placed on the fishing <strong>of</strong> toothfish<br />

in Antarctic waters under the Convention for the Conservation<br />

<strong>of</strong> Antarctic Marine Living Res<strong>our</strong>ces (CCAMLR),<br />

but fish were still caught in large numbers outside the reach<br />

<strong>of</strong> this international agreement. More importantly, pirate<br />

vessels simply ignored the restrictions and caught toothfish<br />

illegally. <strong>The</strong>y funneled them into the market place through<br />

countries where restrictions were lax, and so consumers<br />

could not distinguish the legally-caught from the illegal.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se pirate vessels did more than damage toothfish stocks.<br />

Operating outside the law, they took no seabird avoidance<br />

precautions, and so caught thousands <strong>of</strong> seabirds on their<br />

longline hooks—by some estimates, 100,000 per year. In<br />

1999, following reports that some 80% <strong>of</strong> toothfish sold in<br />

the United <strong>State</strong>s was being caught illegally, (and in anticipation<br />

<strong>of</strong> a government ban that never materialized) Whole<br />

Foods, a supermarket chain that markets to the environmentally<br />

conscious, stopped selling Chilean sea bass. Many<br />

other restaurants and retailers followed suit with the start <strong>of</strong><br />

the “Take a Pass on Chilean Sea Bass” campaign in 2001.<br />

Led by the National Environmental Trust (now the Pew<br />

Environment Group), the campaign called for a U.S. consumer<br />

boycott <strong>of</strong> Chilean sea bass. Hundreds <strong>of</strong> top chefs<br />

and retailers across the nation signed on to the campaign to<br />

pledge that their restaurants and stores would not sell the<br />

fish. Demand soon decreased, and, much to the relief <strong>of</strong> my<br />

friends, I was able to put on hold my personal crusade to<br />

take restaurant managers and chefs to task. By 2003, retail<br />

giant Wal-Mart had agreed to stop selling toothfish, and<br />

things were looking up.<br />

Today<br />

In 2006, the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) surprised<br />

conservationists when they assessed the toothfish fishery<br />

<strong>of</strong>f South Georgia Island in Antarctica as sustainable and<br />

not a threat to seabirds. Whole Foods reversed its boycott<br />

and began to sell MSC-certified sea bass. Soon after, Wal-<br />

Mart followed suit. Conservationists opposed the decision<br />

because it stimulates demand and could undo much <strong>of</strong> the<br />

good that has been accomplished by the boycott.<br />

Research has clearly demonstrated that regulations imposed<br />

by CCAMLR to protect seabirds within its jurisdictional<br />

waters have been an astounding success. In 2007, it was<br />

reported that no albatrosses had been killed in legal fisheries<br />

in the previous two years, a dramatic contrast to bycatch<br />

levels prior to the introduction <strong>of</strong> mitigation measures. Pirate<br />

fishing is down drastically in the enforcement zone too.<br />

Countries such as Australia have sent a clear message <strong>of</strong> zero<br />

tolerance, chasing pirate vessels across thousands <strong>of</strong> miles <strong>of</strong><br />

open ocean on more than one occasion.<br />

Outside <strong>of</strong> CCAMLR waters, however, pirate vessels still<br />

fish with impunity. <strong>The</strong> Pew Environment Group is now<br />

pursuing a binding treaty under the UN Food and Agriculture<br />

Organization that would empower port authorities to<br />

take action against illegal vessels, and require better reporting<br />

<strong>of</strong> landings to help identify pirates. For now, however,<br />

Chilean sea bass sold here not bearing the MSC seal <strong>of</strong><br />

approval should be avoided. With demand beginning to<br />

creep back up, pirate vessels will have greater impetus to<br />

find ways <strong>of</strong> bringing their catch to market, and once again,<br />

when I go out to dinner, I may find myself demanding to<br />

talk to the manager.<br />

Gavin Shire<br />

Director <strong>of</strong> Communications<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Bird</strong> <strong>Conservancy</strong><br />

10<br />

bird conservation • FALL <strong>2008</strong><br />

stock.xchng

Gillnets<br />

Nets: stock.xchng<br />

onglines receive the lion’s share <strong>of</strong> attention when it<br />

comes to seabird bycatch—largely because globally<br />

they pose the greatest threat to some <strong>of</strong> the most<br />

endangered seabirds, including albatrosses and petrels.<br />

But in U.S. waters, gillnet fisheries are now more <strong>of</strong> a<br />

threat to birds, especially since the implementation <strong>of</strong> federally<br />

mandated protection measures that have dramatically<br />

reduced longline bycatch in most U.S. fleets (see page 7).<br />

Gillnets are vertical mesh curtains, suspended in the water<br />

using a combination <strong>of</strong> weights at the bottom and floats at<br />

the top. <strong>The</strong>y can be made to ‘hang’ at any depth, which,<br />

in combination with their mesh size, means they can be<br />

used to target a specific fish species. For example, nets for<br />

cod and flatfish are weighted to touch the sea floor, whereas<br />

nets for salmon, squid, or small pelagic fish hang down<br />

from the ocean surface. Gillnets work when fish attempt to<br />

swim through the curtain. Larger fish cannot pass through<br />

the holes and must go around. Smaller fish can slip right<br />

through the mesh. <strong>The</strong> target species try to swim through<br />

the holes but cannot fit all the way through. <strong>The</strong>y become<br />

entangled when they attempt to back out, snagging their<br />

gills on the mesh.<br />

Although the fishermen target specific fish, non-target<br />

fish, marine mammals, turtles, and diving birds may also<br />

become entrapped. <strong>Bird</strong>s are unable to see the fine nylon<br />

mesh and swim straight into it. Although we might not<br />

think <strong>of</strong> birds as swimmers, many alcids and diving ducks<br />

can reach high speeds under water. Stocky little marine<br />

birds are amazingly agile swimmers. Thick-billed Murres<br />

can plunge to depths <strong>of</strong> over 400 feet in pursuit <strong>of</strong> fish. As<br />

they speed through the water intent on their prey, hard-tosee<br />

gillnets can be fatal. Nets are sometimes anchored just<br />

beyond the surf zone for 24 h<strong>our</strong>s a day, which means that<br />

during spring migration, nets are deployed as new birds are<br />

moving into the richest feeding areas. <strong>The</strong> problem is especially<br />

acute at dawn and dusk, when birds are most actively<br />

feeding, and when the nets are hardest for the birds to see.<br />

Diving ducks, grebes, and loons are similarly vulnerable on<br />

the East Coast <strong>of</strong> the United <strong>State</strong>s and Canada. <strong>The</strong> highest<br />

reports <strong>of</strong> accidental catch are <strong>of</strong> scaup, but mortality<br />

includes Ruddy Ducks, goldeneyes, mergansers, Canvasbacks,<br />

scoters, and Long-tailed Ducks, as well as Common<br />

and Red-throated Loons, and, further north, shearwaters,<br />

puffins, and gannets. One fisherman in North Carolina<br />

reported catching up to 300 scaup in a single night, and another<br />

said that he removed his nets after he began to catch<br />

up to a hundred scaup per day for two or three days in a<br />

row. Multiply this by the total number <strong>of</strong> fishermen, and it<br />

is clear that the threat is potentially large.<br />

<strong>The</strong> threat posed by gillnets is even more marked outside<br />

<strong>of</strong> the United <strong>State</strong>s. Large-scale gillnets or ocean driftnets<br />

were used extensively on the high seas in the 1980s to target<br />

tuna. Because <strong>of</strong> their devastating effect on whales and dolphins,<br />

the United Nations banned their use in international<br />

waters in 1993. Nevertheless, there are still significant gillnet<br />

fisheries in national waters throughout the world.<br />

In Peru, the endangered Humboldt Penguin is particularly<br />

vulnerable to gillnets. Humboldt Penguins have been<br />

clocked swimming at 25 miles per h<strong>our</strong>. At such speeds,<br />

avoiding nets is virtually impossible. In the 1990s, biologists<br />

at the fishing port <strong>of</strong> San Juan, near a large penguin<br />

colony, observed approximately one thousand penguins<br />

caught in nets over a six-year period.<br />

“Ghost-fishing” is another hazard <strong>of</strong> gillnets. Gear that<br />

is lost during storms or for other reasons can continue to<br />

trap birds and other animals for years. Over time, the nets<br />

become sufficiently dirty to be visible to even fast-moving<br />

birds, but they continue to kill fish and litter the oceans.<br />

Are there solutions<br />

Technical solutions to bird bycatch in gillnet fisheries are<br />

not easy to come by because they must also not reduce the<br />

catch <strong>of</strong> the target fish. Ed Melvin and his research team at<br />

Washington Sea Grant studied bycatch<br />

<strong>of</strong> Common Murres and<br />

Rhinoceros Auklets, and found<br />

that solutions must be multifaceted.<br />

“Pingers”, which are devices<br />

that attach to the nets and make a<br />

noise when animals approach, worked<br />

relatively well, but were too expensive<br />

to maintain. Changing the color <strong>of</strong><br />

the upper panel <strong>of</strong> the net also reduced<br />

bird bycatch significantly, but by far the<br />

best overall mitigation was achieved when<br />

these gear modifications were combined<br />

with restrictions on fishing in the early<br />

morning, and limits on the number <strong>of</strong> days<br />

that the nets were active.<br />

Humboldt Penguin:<br />

wikipedia.com<br />

bird conservation • FALL <strong>2008</strong><br />

11

Dead Diving <strong>Bird</strong>s Found in Areas<br />

With Nets and Without Nets<br />

bycatch in the Western Aleutian Islands in the early 1980s<br />

and along the Mid-Atlantic coast in the late 1990s: “We no<br />

longer need exhaustive studies to measure the magnitude<br />

<strong>of</strong> bird bycatch in gillnets. If nets and diving birds are in<br />

the same waters at the same time and we do not change the<br />

nets, the methods, or the fishing season, birds will continue<br />

to die.”<br />

Greater Scaup: Tom Grey<br />

S<strong>our</strong>ce: Doug Forsell, FWS<br />

Hence, thus far, more gillnet seabird bycatch has been<br />

avoided by policy solutions than technical solutions. In<br />

California, conservationists started paying attention to gillnets<br />

when they began to hear reports <strong>of</strong> birds washing up<br />

on beaches. From 1981 to 1986, Common Murre populations<br />

declined from 210,000 to fewer than half that (based<br />

on monitoring at Monterey Bay and in the Gulf <strong>of</strong> the Farallones).<br />

In 1984, one scientist estimated that up to 10,000<br />

birds were being killed each summer month. Sea otters were<br />

also caught in the nets, which rallied a lot <strong>of</strong> public support<br />

for reforms that also benefited birds. <strong>The</strong> problem was<br />

addressed in the California legislature, thanks to the tireless<br />

efforts <strong>of</strong> local activists led by PRBO Conservation Science.<br />

Through a sequence <strong>of</strong> area closures, depth restrictions, and<br />

season-setting, the bycatch problem was solved by the late<br />

1980s, and the murre population rebounded.<br />

Similarly, in Florida, conservationists achieved a policy<br />

solution to their bycatch problems, which included heavy<br />

take <strong>of</strong> turtles. A popular amendment to Florida’s constitution<br />

in 1994 limited marine net fishing. Gillnets were<br />

prohibited in all state waters, and a size limit was placed on<br />

other types <strong>of</strong> nets.<br />

For much <strong>of</strong> the East Coast, however, the problem requires<br />

more work. Though we occasionally hear reports <strong>of</strong> largescale<br />

bird mortality, most gillnet bycatch goes unreported.<br />

<strong>The</strong> National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration<br />

(NOAA) provides observers for some gillnetting operations,<br />

but their objective is primarily to detect mammal bycatch,<br />

and so is not optimal for birds. Finally, the fisheries are<br />

quite variable in location, target, and gear, making both observation<br />

and regulation more difficult. But there is support<br />

for science-based change.<br />

According to Doug Forsell, a seabird biologist with the<br />

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service who first studied gillnet<br />

Strange Bedfellows<br />

As migratory seabirds move from north to south in the<br />

winter, many stop to feed in North Carolina’s inshore<br />

waters. <strong>The</strong>se same waters are home to winter gillnet fisheries<br />

for shad, southern flounder, sea trout, monkfish, and<br />

various other species. <strong>The</strong> commercial and recreational<br />

gillnet fisheries in North Carolina are subject to some<br />

regulations restricting fishing areas, seasons, and gear<br />

specifications, primarily to protect sea turtles, but generally,<br />

North Carolina lags behind its Atlantic seaboard neighbors<br />

in mandating comprehensive restrictions. For example,<br />

unattended gillnets are illegal in South Carolina, whereas in<br />

North Carolina, attendance at gillnets is only mandatory in<br />

certain locations and for certain sizes <strong>of</strong> mesh. As a result,<br />

gillnets are <strong>of</strong>ten left unattended for long periods <strong>of</strong> time,<br />

increasing the probability <strong>of</strong> both accidentally catching<br />

birds, and the likelihood that entangled birds will drown.<br />

Efforts to better monitor these deaths are hampered by gaps<br />

in the commercial gillnet observer program, which lacks<br />

long-term sustainable funding.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Coastal Conservation Association and Audubon North<br />

Carolina recently collaborated in a survey <strong>of</strong> their members,<br />

organized by ABC and students from Duke University, on<br />

the issue <strong>of</strong> bycatch from gillnets. <strong>The</strong> Coastal Conservation<br />

Association is comprised primarily <strong>of</strong> recreational fishermen,<br />

and so has historically been on the opposite side from<br />

Audubon on many issues, such as beach use. However, the<br />

survey showed overwhelming support from both groups for<br />

stricter regulation in North Carolina’s gillnet fishery. Such<br />

synergy <strong>of</strong>fers hope that real change can be brought about<br />

in the near future.<br />

In coming years, <strong>American</strong> <strong>Bird</strong> <strong>Conservancy</strong>, NOAA, the<br />

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the North Western<br />

Atlantic <strong>Bird</strong>s at Sea Conservation Cooperative will be<br />

working together to pinpoint problematic areas along the<br />

Eastern Seaboard, and develop conservation solutions that<br />

will help reduce the threat. ABC will continue to work<br />

with partners in Latin America to improve gillnet fisheries<br />

throughout the Americas.<br />

Thanks to Mallory Dimmitt, a graduate student in the Environmental<br />

Management program at Duke University, for her<br />

help in preparing this article.<br />

12<br />

bird conservation • FALL <strong>2008</strong>

Laysan Albatrosses on Guadalupe Island, Mexico, where<br />

invasive mammals have led to the probable extinction <strong>of</strong><br />

the Guadalupe Storm-Petrel and several other species.<br />

Photo: Bill Henry.<br />

No Guarantee <strong>of</strong> Safe Haven Islands<br />

This time <strong>of</strong> year, many <strong>of</strong> us are thinking <strong>of</strong> islands for <strong>our</strong> vacations, where we can relax on deserted<br />

beaches, surrounded by clear, sparkling waters. <strong>Seabirds</strong> <strong>of</strong>ten select islands for their breeding grounds<br />

for many <strong>of</strong> the same reasons—good beach access and a low probability <strong>of</strong> disturbance. Because the only<br />

denizens <strong>of</strong> remote oceanic islands are those able to fly or swim there, island communities tend to be relatively<br />

simple, with less competition for res<strong>our</strong>ces from other species, and <strong>of</strong>ten free <strong>of</strong> mammalian predators.<br />

Islands are frequently host to unique and delicate biological<br />

communities. Millions <strong>of</strong> years <strong>of</strong> isolation have led to the<br />

emergence <strong>of</strong> thousands <strong>of</strong> new species found nowhere else:<br />

globally, islands represent only 3% <strong>of</strong> the earth’s land mass,<br />

but over 15% <strong>of</strong> its biodiversity. Unfortunately, these oases<br />

in the ocean are particularly vulnerable to disruption <strong>of</strong><br />

their fragile ecological balance. As part <strong>of</strong> their island adaptations,<br />

many species have lost basic defensive skills such<br />

as the fear <strong>of</strong> predators, and in the case <strong>of</strong> some birds such<br />

as rails in the Pacific, the ability to fly. Island animals are<br />

therefore disproportionately imperiled compared to their<br />

mainland kin, and so it is not surprising that most <strong>of</strong> the<br />

world’s extinctions have occurred on islands, and nearly half<br />

<strong>of</strong> the world’s endangered species reside there. Introduced<br />

species are the main factor behind these troubling statistics.<br />

Species Introductions<br />

Humans have learned that introducing species to islands<br />

can have disastrous consequences, and so these days, most<br />

island introductions are accidental. By far the most common<br />

introduced species is the Norway rat, which arrives as<br />

a stowaway on ships. More than 80% <strong>of</strong> the world’s islands<br />

now have rats, which eat both eggs and helpless chicks.<br />

Over 90% <strong>of</strong> bird extinctions in the past three centuries<br />

were island birds, many <strong>of</strong> them made vulnerable or driven<br />

extinct by introduced predators. In the past, however, many<br />

introductions were intentional. For example, trappers and<br />

fur traders introduced mink to the Aleutian Islands and<br />

elsewhere so they could return later to an established but<br />

essentially captive population to collect pelts. Elsewhere,<br />

bird conservation • FALL <strong>2008</strong><br />

13

Introduced sheep have severely impacted vegetation on Socorro Island. such as this endemic tree, Bumelia socorrensis. <strong>The</strong><br />

tree was a favorite <strong>of</strong> the nearly extinct Socorro Dove, which now exists only in captivity. Photo: Island Conservation.<br />

A lone biologist on Rat Island. Once full <strong>of</strong> breeding seabirds, today Rat Island is able to support bird nesting at only<br />

the most minimal level due to the invasive Norway rat. Photo: FWS.<br />

traveling merchants left populations <strong>of</strong> pigs or goats to provide<br />

meat on future voyages. Mongooses were introduced<br />

to Jamaica and Hawaii to control the introduced rats, only<br />

to become bird predators themselves. Some introduced<br />

animals have now been on islands for a very long time. For<br />

instance in Hawaii, the pigs that Europeans first brought<br />

over have formed feral herds, and hunts for them are now<br />

considered “traditional” because the grandparents and great<br />

grandparents <strong>of</strong> today’s residents hunted those same herds.<br />

Plant introductions are just as common, but have attracted<br />

less attention. Seeds or insects in produce or cargo brought<br />

to islands can sometimes establish populations, but plants<br />

are more likely to be intentionally brought to islands as ornamentals<br />

in gardens, or to serve as ground cover or erosion<br />

control. However they get there, plants that are new to an<br />

island compete with the native plants. Some invasives can<br />

take over an island entirely, once established.<br />

In general, the probability that an introduced species will<br />

establish a wild population are slim—imagine a flock <strong>of</strong> parrots<br />

trying to survive in Antarctica—but the sheer numbers<br />

<strong>of</strong> introduction events over history have meant that there are<br />

many more islands with introduced species than without.<br />

Effects on <strong>Seabirds</strong><br />

Introduced species <strong>of</strong> plants and animals are one <strong>of</strong> the<br />

foremost threats to seabirds as a group. <strong>Seabirds</strong> tend to<br />

nest in dense colonies and lay large, tempting eggs, which<br />

produce large, tempting chicks that take months to mature.<br />

Introduced predators, capable <strong>of</strong> living on eggs or young,<br />

can thrive and increase their populations rapidly. On<br />

Gough Island, which lies almost in the center <strong>of</strong> the southern<br />

Atlantic, the endangered Tristan Albatross loses 60% <strong>of</strong><br />

its young every year to mice (which have evolved to twice<br />

their original size on the island!). Even a few individual<br />

predators can wreak havoc on island bird populations.<br />

Perhaps the most famous case is that <strong>of</strong> the Stephens Island<br />

Wren, which was driven to extinction by cats on this tiny<br />

island <strong>of</strong>f the coast <strong>of</strong> New Zealand.<br />

<strong>The</strong> critically endangered Townsend’s Shearwater is endemic<br />

to the Revillagigedo Archipelago <strong>of</strong>f western Mexico. On<br />

one <strong>of</strong> its breeding islands, Clarion, the entire shearwater<br />

colony was destroyed because introduced pigs dug up and<br />

ate eggs, nestlings, and adults. At the only remaining colony<br />

on Socorro Island, feral cats are rapidly eating away at the<br />

remaining population <strong>of</strong> Townsend’s Shearwaters, and<br />

introduced sheep are destroying its nesting habitat.<br />

An auklet egg destroyed by rats on Kiska Island in Alaska. Invasive Norway<br />

rats have pushed many species to the brink <strong>of</strong> extinction. Photo: FWS.<br />

Townsend’s Shearwater chick on Socorro:<br />

Juan Martinez/Island Endemics.<br />

14<br />

bird conservation • FALL <strong>2008</strong>

Laysan Albatross chick, almost lost amidst Verbesina plants that have sprung up since the chick hatched.<br />

Christy Finlaysan.<br />

A biologist trekking through Adak Island in the Aleutians. Photo: Island Conservation<br />

On Midway Atoll, golden crown-beard (Verbesina) is growing<br />

rampantly and choking out the native vegetation. This<br />

relative <strong>of</strong> the daisy grows so rapidly that adult Laysan<br />

Albatrosses are sometimes unable to reach their chicks<br />

that have become isolated behind a wall <strong>of</strong> vegetation. <strong>The</strong><br />

chicks die <strong>of</strong> starvation or dehydration.<br />

Solutions<br />

<strong>The</strong>re are literally hundreds <strong>of</strong> examples <strong>of</strong> islands with<br />

such problems. However, there are also opportunities for<br />

conservationists to reverse the situation. For example,<br />

Grupo de Ecología y Conservación de Islas A.C. and Island<br />

Conservation are currently planning to remove first the<br />

introduced sheep then the feral cats from Socorro. <strong>The</strong> 13<br />

species <strong>of</strong> seabirds that may once have nested on Rat Island,<br />

at the tip <strong>of</strong> the Aleutian Islands, will soon have the opportunity<br />

to nest again thanks to a rat eradication project<br />

by <strong>The</strong> Nature <strong>Conservancy</strong>, the Alaska Maritime National<br />

Wildlife Refuge, and Island Conservation. But the work is<br />

easier said than done.<br />

Xantus’s Murrelets have benefited from the removal <strong>of</strong> black rats from Anacapa Island, with<br />

breeding success increasing by 155% as <strong>of</strong> July 2007. Photo: National Park Service.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re have been efforts to remove invasive alien animals<br />

from islands for over 200 years, but large scale eradications<br />

and island restorations are relatively new to conservationists.<br />

Rats have now been successfully eliminated from more<br />

than 200 islands, and feral cats from at least 48. <strong>The</strong> results<br />

can be quick and dramatic. Xantus’s Murrelets on Anacapa<br />

Island <strong>of</strong>f the coast <strong>of</strong> California made an astounding 80%<br />

leap in nesting success within one year <strong>of</strong> removing rats.<br />

<strong>The</strong> U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) operates an<br />

ambitious campaign to restore the biological integrity <strong>of</strong><br />

the Aleutian Islands <strong>of</strong>f Alaska. One <strong>of</strong> the most striking<br />

examples <strong>of</strong> their success was that <strong>of</strong> the Aleutian Cackling<br />

Goose, which was on the brink <strong>of</strong> extinction until the mid<br />

1990s, when FWS stepped up control <strong>of</strong> the foxes that had<br />

been introduced to its nesting grounds more than 70 years<br />

before. <strong>The</strong> goose population rebounded quickly from a<br />

low <strong>of</strong> 300 birds to 30,000, and in 2001, it was removed<br />

from the endangered species list.<br />

Even with sophisticated techniques available to biologists<br />

today, the effort required to clear an island is considerable.<br />

For example, in rat eradications, thousands <strong>of</strong> pounds <strong>of</strong><br />

poison must be aerially distributed to cover an entire island<br />

in a manner that will not put the birds themselves at risk.<br />

<strong>The</strong> process requires painstaking attention to detail before,<br />

during, and after the operation, and the price <strong>of</strong> failure is<br />

high. A single island eradication can cost upwards <strong>of</strong> $2<br />

million to complete, yet leaving even a few rats alive will<br />

render the entire exercise useless in no time at all. And rats<br />

are no easy opponent! Just ask James Russell.<br />

As a graduate student, Russell radio collared a single rat, to<br />

try to learn more about its behavior and movements. Upon<br />

release, the rat promptly took <strong>of</strong>f and the race was on. After<br />

a few nights <strong>of</strong> tracking the rat’s movements, Russell was<br />

ready to capture it and end the study, but the rat had other<br />

ideas, and led researchers on a fantastic chase. <strong>The</strong> rat eluded<br />

capture for two months <strong>of</strong> dawn-to-dusk radio tracking,<br />

until it finally disappeared from the island, never having<br />

been sighted. Russell declared it missing presumed dead<br />

until visitors from a nearby island reported a radio-tagged<br />

rat there. <strong>The</strong> passage was hard to imagine, almost comical.<br />

For mysterious reasons <strong>of</strong> its own, the rat had struck out<br />

from the island swimming across over 400 yards <strong>of</strong> open<br />

ocean. Again, Russell was on its tail, this time with traps<br />

and rat-sniffing dogs to carry on the hunt. Still, it was three<br />

bird conservation • FALL <strong>2008</strong> 15

months before the rat was caught. This underscores the difficulties<br />

faced by conservationists who must eliminate every<br />

last island invader to claim success.<br />

<strong>The</strong> slow, technically difficult, and rigorous process <strong>of</strong><br />

island eradication is an exciting frontier in avian conservation.<br />

Yet to restore these complex biological systems, even<br />

successful eradication isn’t the end <strong>of</strong> the story.<br />

Island Recovery: <strong>Bird</strong>s as<br />

Architects <strong>of</strong> Island Habitats<br />

Now that some <strong>of</strong> the techniques for ridding the island<br />

<strong>of</strong> invasives are in place, scientists are beginning to take a<br />

more careful look at what happens after eradication. Some<br />

<strong>of</strong> these islands were changed over a hundred years ago as<br />

a result <strong>of</strong> introduced species, and what was once a seabird<br />

paradise might now be altered beyond recognition. This is<br />

in part because the birds themselves have such a pr<strong>of</strong>ound<br />

effect on the landscape.<br />

Biologist Christa Mulder was face down, wriggling across a<br />

nesting colony on Stephens Island, New Zealand, when she<br />

had a small revelation. She had avoided walking so that she<br />

wouldn’t crush the delicate sand burrows beneath the surface<br />

<strong>of</strong> the soil, where Fairy Prions were nesting. Looking<br />

around the colony, it struck her how radically the seabirds<br />

had altered that part <strong>of</strong> the island. In these areas with high<br />

densities <strong>of</strong> nesting burrows, the landscape was completely<br />

different from elsewhere. <strong>The</strong> soil was loose and easily<br />

blown by the wind, which made the local trees prone to<br />

losing their grip and falling. <strong>The</strong> birds also actively grabbed<br />

vegetation, pulling it down into their burrows, leaving<br />

very little on the surface. Such changes to the plants have<br />

Christa Mulder conducting research on Fairy Prions<br />

on Middle Island: M. Durrett.<br />

a pr<strong>of</strong>ound effect on the rest <strong>of</strong> the environment, from the<br />

invertebrates that eat the vegetation to the land birds and<br />

lizards that feed on those invertebrates, and so on throughout<br />

the island ecosystem.<br />

In other colonies, seabirds have different effects on the ecology.<br />

On many islands, seabirds play an important role in<br />

natural soil fertilization, because their waste provides most<br />

<strong>of</strong> the nutrient s in the system. Christa began to wonder if<br />

all <strong>of</strong> these complicated interactions might have effects on<br />

island eradication projects. What if simply removing the<br />