Government-wide Financial Reporting - AGA

Government-wide Financial Reporting - AGA

Government-wide Financial Reporting - AGA

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Corporate Partner<br />

Research<br />

Advisory Group<br />

Series<br />

Report No. 31 July 2012<br />

<strong>Government</strong>-<strong>wide</strong><br />

<strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Reporting</strong>

Acknowledgements<br />

About the Authors<br />

Bert T. Edwards, CGFM, CPA, CGMA, was the lead researcher for this project. An<br />

independent consultant since his 2010 retirement as Executive Director of the Office of<br />

Historical Trust Accounting at the U.S. Department of the Interior, Edwards previously<br />

served as CFO of the U.S. Department of State. After a successful 33-year career at<br />

Arthur Andersen LLP as its world<strong>wide</strong> industry head for government, higher education<br />

and nonprofit industries, Edwards served as a consultant for the World Bank and<br />

USAID in Vietnam, Moldova, Palestine and Germany and also lectured extensively for<br />

the AICPA and accounting firms on government accounting and auditing issues.<br />

Principal contributors to this report were: Daniel J. Murrin, CGFM, CPA, from<br />

Ernst & Young; John R. Cherbini, CGFM, CPA, CGMA, and Carlos A. Otal, CPA, from<br />

Grant Thornton LLP; Ronald Longo, CGFM, CPA, and David M. Zavada, CPA, from<br />

Kearney & Company; Andrew C. Lewis, CGFM, CPA, CIPP/G, and Jeffrey C. Steinhoff,<br />

CGFM, CPA, CFE, CGMA, from KPMG LLP; Joseph L. Kull, CGFM, CPA, CGMA, from<br />

PwC; and Ann Davis, CGFM, CPA, as Treasury Liaison.<br />

Other contributors were: Werner Lippuner, CISA, CISM, and Danila Weatherly<br />

from Ernst & Young; and Demek M. Adams, CGFM, from Grant Thornton LLP.<br />

The authors would also like to acknowledge the efforts of Lynn Hoffman and<br />

Maryann Malesardi on this project.<br />

Corporate Partner Advisory Group<br />

Chairman:<br />

Hank Steininger, CGFM, CPA<br />

Managing Partner, Global Public Sector,<br />

Grant Thornton, LLP<br />

<strong>AGA</strong> Professional Staff:<br />

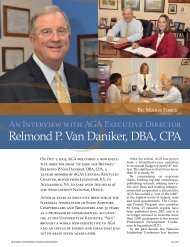

Relmond Van Daniker, DBA, CPA<br />

Executive Director<br />

Susan Fritzlen<br />

Deputy Executive Director/COO<br />

Lynn Hoffman<br />

Programs Coordinator<br />

Maryann Malesardi<br />

Director of Communications<br />

<strong>AGA</strong> is proud to recognize our sponsors for supporting this effort.<br />

<strong>AGA</strong>’s Corporate Partner Advisory Group Research Program<br />

One of the roles of professional<br />

associations like <strong>AGA</strong> is to develop new<br />

thinking on issues affecting those we<br />

represent. This new thinking is developed<br />

out of research and draws on the<br />

considerable resources and experiences<br />

of our members and counterparts in the<br />

private sector – our Corporate Partners.<br />

These organizations all have long-term<br />

commitments to supporting the financial<br />

management community and choose to<br />

partner with and help <strong>AGA</strong> in its mission<br />

of advancing government accountability.<br />

<strong>AGA</strong> has been instrumental in<br />

assisting the development of accounting<br />

and auditing standards and in<br />

generating new concepts for the effective<br />

organization and administration<br />

of government financial management<br />

functions. The Association conducts<br />

independent research and analysis of<br />

all aspects of government financial<br />

management. These studies make <strong>AGA</strong><br />

a leading advocate for improving the<br />

quality and effectiveness of government<br />

fiscal administration and program<br />

performance and accountability.<br />

Our Thought Leadership Library<br />

includes more than thirty completed<br />

studies. These in-depth studies are<br />

made possible with the support of our<br />

Corporate Partners. Download complimentary<br />

reports at www.agacgfm.org/<br />

researchpublications.<br />

2<br />

<strong>AGA</strong> Corporate Partner Advisory Group Research

Table of Contents<br />

Executive Summary. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4<br />

1. Introduction ................................................................................................... 6<br />

Historical Perspective ......................................................................................... 6<br />

The Research ................................................................................................. 8<br />

Research Project Scope and Methodology ....................................................................... 8<br />

2. Breakdowns in the Compilation Process: Bridging Budgetary and Other Critical Information ............................. 9<br />

Issue ........................................................................................................ 9<br />

Analysis .................................................................................................... 10<br />

Data Flows Supporting the Compilation Process ................................................................. 11<br />

Bridging Unaudited Budgetary Information to Audited Balances ................................................... 13<br />

Identifying and <strong>Reporting</strong> the Differences Between the Unified Budget Deficit, Net Operating Cost<br />

and the Changes in Cash Needed to Populate the CFS Reconciliation Statements ..................................... 13<br />

A Related Initiative ........................................................................................... 14<br />

Short-Term Recommendations ................................................................................ 14<br />

Long-Term Recommendation .................................................................................. 16<br />

3. Usefulness of the Two CFS Reconciliation Statements ............................................................. 17<br />

Issue ....................................................................................................... 17<br />

Reconciliation of Net Cost Is a Critical <strong>Financial</strong> Statement Within the CFS ........................................... 17<br />

Improving the Statement of Changes in Cash .................................................................... 18<br />

Short-Term Recommendation ................................................................................. 18<br />

4. Structure ..................................................................................................... 19<br />

Overview of the As-Is Environment ............................................................................. 19<br />

Interviews .................................................................................................. 20<br />

Observations ................................................................................................ 20<br />

Short-Term Recommendations ................................................................................ 21<br />

Long-Term Recommendation .................................................................................. 22<br />

Appendix A: Summary of Important Actions Leading to the Current<br />

Consolidated <strong>Financial</strong> Statements of the U.S. <strong>Government</strong> .......................................................... 24<br />

Appendix B: Clarification on Data Format in Statement of Cash ....................................................... 27<br />

Appendix C: Interviews with State, Private-Sector and U.S. <strong>Government</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> Officials ............................... 28<br />

Appendix D: Abbreviations and Acronyms .......................................................................... 33<br />

Appendix E: <strong>AGA</strong> Treasury Review Scope and Methodology Research Project — Summary of Project Meetings ............. 35<br />

<strong>Government</strong>-<strong>wide</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Reporting</strong> 3

Executive Summary<br />

For its audit of the 2011 federal<br />

government consolidated financial<br />

statements (CFS), the <strong>Government</strong><br />

Accountability Office (GAO) reported<br />

that the U.S. Department of the<br />

Treasury’s (Treasury) process for compiling<br />

the CFS generally demonstrated that<br />

amounts reported were consistent with<br />

the underlying federal agencies’ audited<br />

financial statements. However, GAO<br />

reported that Treasury’s process did<br />

not ensure that the (1) Reconciliations<br />

of New Operating Cost and the Unified<br />

Budget Deficit and (2) Statements of<br />

Changes in Cash Balances from the<br />

Unified Budget and Other Activities<br />

were fully consistent with underlying<br />

information in audited agency financial<br />

statements and other financial data. 1<br />

This aspect of the compilation process<br />

significantly contributes to a recurrent<br />

material weakness in Treasury’s<br />

compilation for all 15 years GAO has<br />

attempted to audit the CFS. This material<br />

weakness is one of three major impediments<br />

to GAO rendering an opinion on<br />

the CFS. Therefore, the Association of<br />

<strong>Government</strong> Accountants (<strong>AGA</strong>) took on<br />

this research project with an objective<br />

of developing actionable recommendations<br />

that address the root cause of this<br />

long-standing problem.<br />

In its ultimate simplicity, imagine<br />

information flowing between each<br />

federal agency and Treasury’s <strong>Financial</strong><br />

Management Service (FMS), which<br />

compiles the CFS. One set of information<br />

is flowing on an accrual basis and<br />

the other on a budgetary basis that<br />

is largely cash-based. Both types of<br />

information are reported in the CFS.<br />

For the most part, the accrual information<br />

flow between the agencies and<br />

Treasury, for preparation of the CFS, is<br />

reasonably well documented, and the<br />

underlying information can be reconciled<br />

to that in the audited agencies’<br />

financial statements. The same does<br />

not hold true, however, for budgetary<br />

information included in the two financial<br />

statements cited in the first paragraph.<br />

Arguably, budgetary information is<br />

the most useful financial information<br />

government-<strong>wide</strong> and within an agency.<br />

Yet the continuing need for a transparent<br />

reconciliation process between agency<br />

and government-<strong>wide</strong> budgetary balances<br />

has inhibited the audit of probably<br />

the most quoted and used number in the<br />

CFS — the Unified Budget Deficit.<br />

A major improvement would be to<br />

compile and validate budgetary information<br />

in a fashion similar to the accrual<br />

flow. Our research identified specific<br />

technical recommendations that begin<br />

this process and, if properly designed<br />

and implemented, should resolve this<br />

component of Treasury’s compilation<br />

material control weakness and move the<br />

federal government closer to the goal<br />

of achieving an unqualified (“clean”)<br />

auditors’ opinion on the CFS.<br />

Equally if not more important to<br />

success are issues related to structure<br />

and organization. Several themes consistently<br />

came up during our research,<br />

particularly in our discussions with state<br />

and corporate officials: the importance<br />

of clear purpose and priority, financial<br />

authority and responsibility, adequate<br />

resources, and standardization and<br />

centralization. These themes remain a<br />

challenge to the federal government,<br />

and any technical solution would need<br />

to be combined with the type of structural<br />

and organizational changes we are<br />

recommending.<br />

Finally, we were struck by how far<br />

federal government financial management<br />

has come in the 20-plus years<br />

since enacting the Chief <strong>Financial</strong><br />

Officers (CFO) Act. 2 The improvement<br />

has been nothing short of remarkable<br />

given the size and complexity of the<br />

federal government and how far it had<br />

to come.<br />

Given this “higher playing field,”<br />

continuing technological advances,<br />

constrained resources and the need for<br />

an open, transparent government, this<br />

is an opportune time to begin to put the<br />

pieces in place to define and achieve<br />

a future vision. The goal should be<br />

relatively simple — to provide reliable,<br />

timely and interactive information to<br />

4<br />

<strong>AGA</strong> Corporate Partner Advisory Group Research

Executive Summary<br />

SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS<br />

Short-Term Recommendations<br />

manage, demonstrate accountability<br />

and enable an open, transparent government.<br />

One could easily envision an<br />

environment where a real-time system<br />

generates standardized data, providing<br />

reliable, citizen-driven financial reports.<br />

The accounting here is relatively<br />

straightforward, and strong leadership<br />

with a sharp focus and appropriate<br />

authority can make this type of reporting<br />

and underlying process routine. Highperforming<br />

organizations take both the<br />

“clean” auditors’ opinions and the lack<br />

of weaknesses in internal control over<br />

financial reporting and reliable, timely<br />

information for granted — and rightfully<br />

so, since these are critical to their survival<br />

and sustainability. The American<br />

public should demand no less from its<br />

government.<br />

• Enhance the Closing Package process to include reconciliation and<br />

audit of budgetary data.<br />

• Reconcile and audit budgetary information reported in audited<br />

agency financial statements with gross receipt and outlay<br />

information in Treasury’s central accounting system.<br />

• Identify, report and audit the major differences between the Unified<br />

Budget Deficit and Net Operating Cost, and changes in cash to<br />

populate the consolidated level.<br />

• Include all information needed to complete the reconciliation<br />

statements in the Treasury’s Closing Package process.<br />

• Perform a hard close, compile the CFS and begin the CFS audit<br />

process at the end of the third quarter.<br />

• Modify the Statement of Changes in Cash to provide additional<br />

gross receipt and outlay data and change the compilation process<br />

as needed to capture this information.<br />

• Re-energize the Joint <strong>Financial</strong> Management Improvement<br />

Program by engaging the principals and reconstituting the<br />

steering committee.<br />

• Issue a Presidential Executive Order reaffirming the importance<br />

of a “clean opinion” on the CFS.<br />

• Establish a separate organization reporting to the Fiscal Assistant<br />

Secretary, focused solely on supporting preparation of the CFS, and<br />

augment resources as needed.<br />

• Establish clear responsibility and time frames for corrective actions.<br />

Long-Term Recommendations<br />

• Pursue a more centralized approach to standardizing, collecting,<br />

analyzing and reporting financial information.<br />

• Establish a separate organization in the executive branch responsible<br />

for financial operations, systems, controls and reporting, including<br />

the CFS.<br />

<strong>Government</strong>-<strong>wide</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Reporting</strong> 5

1. Introduction<br />

Over the past 15 years, Treasury,<br />

in cooperation with the Office of<br />

Management and Budget (OMB), has<br />

issued the annual <strong>Financial</strong> Report of<br />

the U.S. <strong>Government</strong> (FR), presenting<br />

the financial position and condition of<br />

the nation. For each of those years, the<br />

U.S. <strong>Government</strong> Accountability Office<br />

(GAO) has issued a disclaimer of audit<br />

opinion on the CFS of the federal government,<br />

which is included in the FR.<br />

The recent economic downturn has<br />

focused the nation on its large budget<br />

deficits, continually rising debt and<br />

the federal government’s long-term<br />

fiscal sustainability. Additionally, a<br />

major credit rating agency has downgraded<br />

the bond rating of the federal<br />

government, which has long enjoyed<br />

the highest credit rating. Against this<br />

backdrop, it is especially important<br />

that the federal government be able to<br />

demonstrate its ability to navigate an<br />

annual audit of the CFS — fundamental<br />

to any organization — and provide the<br />

level of assurance that a “clean” auditors’<br />

opinion represents.<br />

In May 2011, the Association of<br />

<strong>Government</strong> Accountants (<strong>AGA</strong>) undertook<br />

an independent research study to<br />

develop recommendations and a plan of<br />

action to address a material GAO-cited<br />

weakness at Treasury that contributes<br />

to GAO’s disclaimer of opinion on the<br />

federal government CFS. Specifically,<br />

this long-standing, unresolved issue<br />

pertains to the identified weaknesses in<br />

the current reconciliation and compilation<br />

processes Treasury employs to<br />

consolidate some 150 federal agencies’<br />

financial data into the CFS.<br />

The research project was built<br />

on interviews with knowledgeable<br />

individuals and organizations affiliated<br />

with the compilation, reconciliation and<br />

associated audit processes. We had a<br />

series of meetings with Treasury, OMB,<br />

GAO and federal government agencies.<br />

We also interviewed representatives<br />

from three state governments (New<br />

York, Massachusetts and Pennsylvania)<br />

and the independent auditors of<br />

Maryland, as well as two large multinational<br />

corporations (IBM and Marriott)<br />

to learn about their practices and experiences<br />

gained from across the governmental<br />

and private sectors. Finally, we<br />

interviewed former Treasury Secretary<br />

Paul O’Neill, who led the charge for<br />

accelerated financial reporting at both<br />

Alcoa and in the federal government.<br />

<strong>AGA</strong> established a Research Team<br />

that collectively has several hundred<br />

years of senior leadership experience<br />

in government financial management,<br />

reporting and systems. The team<br />

was led by the former CFO of the U.S.<br />

Department of State and included<br />

former senior officials from Treasury,<br />

OMB and GAO.<br />

Historical Perspective<br />

The journey to the CFS began<br />

in 1950, with the enactment of the<br />

Budget and Accounting Procedures<br />

Act (BAPA). 3 In the Treasury <strong>Financial</strong><br />

Manual, Part 2, Chapter 1000, 4 the following<br />

citation appears:<br />

“Per the Budget and Accounting<br />

Procedures Act of 1950, Treasury<br />

must render overall <strong>Government</strong><br />

financial reports to the President, the<br />

Congress, and the public. Per this<br />

Act, each agency must provide the<br />

Secretary of Treasury (the Secretary)<br />

with reports and information relating<br />

to the agency’s financial condition<br />

and operations as the Secretary may<br />

require for effective performance.<br />

The Secretary’s responsibilities<br />

include the system of central<br />

accounting and financial reporting<br />

for the <strong>Government</strong>.”<br />

President Harry Truman, who signed<br />

BAPA into law, expressed his thoughts<br />

on the legislation: 5<br />

“The accounting and auditing<br />

provision [of BAPA] lay the foundation<br />

for far-reaching improvements<br />

and simplification. For the first time,<br />

clear-cut legislation is provided<br />

which nails down responsibility for<br />

accounting, auditing, and financial<br />

reporting in the <strong>Government</strong>. … A<br />

6<br />

<strong>AGA</strong> Corporate Partner Advisory Group Research

Introduction<br />

sound system of accounting in each<br />

agency, appropriately integrated<br />

for the <strong>Government</strong> as a whole,<br />

is fundamental to responsible<br />

and efficient administration in the<br />

<strong>Government</strong>.”<br />

While BAPA resulted in important<br />

improvements, its promise was not<br />

fully realized until subsequent financial<br />

management reform legislation more<br />

than 30 years later, which is summarized<br />

later in the document. This reform<br />

legislation revitalized the focus on<br />

financial management and reporting and<br />

included a requirement to prepare the<br />

CFS and have them be audited by GAO.<br />

The federal government has taken<br />

a lengthy journey since the enactment<br />

of the Federal Managers’ <strong>Financial</strong><br />

Integrity Act of 1982, 6 and a number of<br />

other acts throughout the intervening<br />

years (see Appendix A). In particular,<br />

since the 1990 passage of the Chief<br />

<strong>Financial</strong> Officers (CFO) Act, much has<br />

been accomplished to move the federal<br />

government’s financial operations and<br />

reporting to its current state. Widely<br />

heralded as the most comprehensive<br />

financial management improvement in<br />

40 years, the CFO Act ushered in a new<br />

era of federal government accountability.<br />

It significantly changed the landscape<br />

for federal government agency<br />

CFOs, moving the CFO’s role far beyond<br />

basic accounting responsibilities to<br />

that of an agency’s leader in providing<br />

support across a range of critical<br />

programs and operations. 7 But one<br />

achievement that remains elusive is the<br />

ability to prepare consolidated financial<br />

statements for the federal government<br />

as a whole that can obtain a “clean”<br />

auditors’ opinion from GAO.<br />

Among a range of requirements to<br />

reform federal government financial<br />

management practices and capabilities,<br />

the CFO Act required 10 selected<br />

federal government agencies to prepare<br />

audited financial statements beginning<br />

with fiscal year 1992. In commenting<br />

on the requirement for audited agency<br />

financial statements, GAO provided the<br />

following insight:<br />

“Most importantly, the act requires<br />

that financial statements be prepared<br />

and audited. ... Together, these<br />

features of the CFO Act will improve<br />

the reliability and usefulness of<br />

Agency financial information.” 8<br />

The requirement for audited agency<br />

financial statements was later made<br />

permanent and expanded to all 24 CFO<br />

Act agencies with the enactment of<br />

the <strong>Government</strong> Management Reform<br />

Act of 1994 (GMRA), 9 and the requirement<br />

was then expanded even further<br />

to other federal government agencies<br />

by the Accountability of Tax Dollars<br />

Act of 2002 (ATDA). 10 The GMRA also<br />

included a requirement for Treasury to<br />

prepare auditable CFS for the federal<br />

government beginning with fiscal year<br />

1997. Preparing the CFS was not new<br />

for Treasury, which was at the forefront<br />

of producing prototype statements<br />

beginning in 1973. 11<br />

Over the past two decades, because<br />

of the implementation of the CFO Act<br />

and the GMRA, significant change<br />

has occurred regarding how financial<br />

management is viewed in the federal<br />

government. <strong>Financial</strong> management is<br />

now an essential component of agency<br />

management to help ensure accountability<br />

and provide valuable information<br />

and enhanced internal controls.<br />

Today, the CFO leadership structure is<br />

focused on the issues and considers the<br />

future much more broadly than it did<br />

even five years ago. The CFO Council,<br />

established by the CFO Act, undertakes<br />

a variety of initiatives and has provided<br />

a forum to address issues on a government-<strong>wide</strong><br />

basis.<br />

Even with all the progress made<br />

in federal financial management,<br />

upon completion of its CFS audit in<br />

December 2011 for the fiscal year<br />

ending September 30, 2011, GAO — for<br />

the 15th consecutive year — could not<br />

express an opinion on the consolidated<br />

financial statements. 12<br />

<strong>Government</strong>-<strong>wide</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Reporting</strong> 7

Introduction<br />

The Research<br />

In its role as the premier association<br />

for advancing government accountability,<br />

<strong>AGA</strong> undertook this government<strong>wide</strong><br />

financial reporting research<br />

project to provide independent,<br />

objective insight to help Treasury and<br />

the federal government overcome the<br />

long-standing CFS preparation issues<br />

that impede the ability to receive an<br />

unqualified auditors’ opinion.<br />

The primary objective of the<br />

research project was to develop actionable<br />

recommendations that address the<br />

root causes of the long-standing material<br />

weakness in Treasury’s process for<br />

compiling the CFS that contribute to<br />

GAO’s disclaimer of opinion on the CFS.<br />

To meet our objective, we assessed the<br />

preparation and compilation process<br />

for the CFS. We specifically focused on<br />

these areas:<br />

CFS compilation process<br />

Usefulness of the Statement of<br />

Changes in Cash, which is part of<br />

the CFS<br />

Leadership and structural issues<br />

Research Project Scope<br />

and Methodology<br />

In his letter in the 2011 FR related to<br />

the CFS, the Comptroller General of the<br />

United States, the Honorable Gene L.<br />

Dodaro, stated the following:<br />

consolidated financial statements.”<br />

While Defense and Treasury are<br />

continuing to make strides in addressing<br />

the first two impediments, it should<br />

be noted that the scope of this research<br />

project is limited to the material weakness<br />

underlying the third impediment.<br />

Specifically, GAO cited the following:<br />

“… inadequate systems, controls,<br />

and procedures to ensure that the<br />

consolidated financial statements<br />

are consistent with the underlying<br />

audited entity financial statements,<br />

properly balanced, and in conformity<br />

with U.S. generally accepted<br />

accounting principles (GAAP).”<br />

The compilation process for and<br />

the content of the Statement of Social<br />

Insurance and Changes in Social<br />

Insurance within the CFS are not within<br />

the scope of this research project.<br />

The research team conducted 20<br />

interviews with state government<br />

and corporate executives, as well as a<br />

number of Treasury, FMS, OMB, GAO<br />

and federal agency officials. A summary<br />

of the project meetings, including<br />

a list of interviewees, is contained in<br />

Appendix E.<br />

“… three major impediments<br />

continued to prevent us from<br />

rendering an opinion on the federal<br />

government’s accrual-based<br />

consolidated financial statements<br />

over this period: (1) serious financial<br />

management problems at the DOD<br />

that have prevented its financial<br />

statements from being auditable, (2)<br />

the federal government’s inability to<br />

adequately account for and reconcile<br />

intra-governmental activity and<br />

balances between federal agencies,<br />

and (3) the federal government’s<br />

ineffective process for preparing the<br />

8<br />

<strong>AGA</strong> Corporate Partner Advisory Group Research

2. Breakdowns in the Compilation<br />

Process: Bridging Budgetary and<br />

Other Critical Information<br />

Issue<br />

The government-<strong>wide</strong> CFS contains<br />

both accrual-basis (proprietary) and<br />

cash-basis budgetary financial data.<br />

Treasury’s compilation of the CFS<br />

includes a process to capture accrual<br />

accounts from audited agency financial<br />

statements and successfully link them<br />

to CFS line items. There is no similar<br />

process in place to link audited budgetary<br />

balances to the CFS. Similarly, no<br />

reliable process exists to identify and<br />

report all items needed to reconcile the<br />

Unified Budget Deficit to Net Operating<br />

Cost and the change in cash balance<br />

government-<strong>wide</strong>. The budgetary<br />

balances and reconciling line items<br />

reported in the CFS are derived primarily<br />

from unaudited sources at Treasury<br />

rather than audited agency financial<br />

statements. Differences between the<br />

Unified Budget Deficit, Net Operating<br />

Cost and the changes in cash government-<strong>wide</strong><br />

are developed from analytical<br />

procedures applied by Treasury in<br />

preparation of the CFS.<br />

OMB and generally accepted<br />

accounting principles (GAAP) require<br />

agencies to report net outlays in their<br />

Statements of Budgetary Resources<br />

(SBRs). The CFS also includes two<br />

required statements that include<br />

net outlays as part of the Unified<br />

Budget Deficit. These statements are<br />

the Reconciliation of Net Operating<br />

Costs and Unified Budget Deficit and<br />

the Statement of Changes in Cash<br />

Balance from Unified Budget and Other<br />

Activities (Statement of Changes in<br />

Cash) (see Chapter 3 for a discussion<br />

of the relevance of the two CFS reconciliation<br />

statements). The net outlay<br />

information reported on audited agencies’<br />

SBRs and reported in the CFS are<br />

intended to represent the same amount<br />

and be consistent with information<br />

presented in the budget of the federal<br />

government. They should also be<br />

consistent with information included in<br />

Treasury’s annual Combined Statement<br />

of Receipts, Outlays, and Balances<br />

of the U.S. <strong>Government</strong> (Combined<br />

Statement).<br />

In 1997, GAO first reported that the<br />

federal government: 13<br />

“… does not have a process to<br />

obtain information to effectively reconcile<br />

the reported change in net position<br />

… and the reported budget deficit.”<br />

GAO noted that significant differences<br />

existed between the total net<br />

outlays reported in audited agencies’<br />

SBRs and the records Treasury used<br />

to prepare the CFS. Over the past 15<br />

years, the net differences between the<br />

total net outlays in selected agencies’<br />

SBRs and the records Treasury uses to<br />

prepare the CFS have ranged from $28<br />

billion in fiscal year 2009 to $140 billion<br />

in fiscal year 2003, with the most recent<br />

net difference of $31 billion in fiscal<br />

year 2011. 14<br />

The inability to reconcile budgetary<br />

and accrual accounting has also been<br />

continuously reported over the past 15<br />

years. GAO has consistently noted that<br />

Treasury does not have a systematic<br />

process in place to capture audited budgetary<br />

information and the significant<br />

components or reconciling line items,<br />

between the Unified Budget Deficit,<br />

Net Operating Cost and the changes<br />

in cash reported in the CFS. While the<br />

overwhelming majority of financial<br />

information used to compile the CFS is<br />

derived from audited agency financial<br />

statements, budgetary receipts and<br />

outlays are not. They are derived from<br />

Net differences between the total net outlays<br />

in agencies’ SBRs have ranged from a low of<br />

$28 billion to a high of $140 billion.<br />

<strong>Government</strong>-<strong>wide</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Reporting</strong> 9

Breakdowns in the Compilation Process<br />

Treasury’s central accounting system,<br />

based on unaudited periodic agency<br />

reports. The lack of an audit trail<br />

between audited budgetary information<br />

reported at the agency level and budgetary<br />

information in the CFS reflects a<br />

breakdown in the compilation process<br />

used by Treasury.<br />

The information needed to reconcile<br />

operating results on the accrual basis<br />

to the budget results (Unified Budget<br />

Deficit) and to reconcile the Unified<br />

Budget Deficit with the change in cash<br />

balance may in some cases be derived<br />

from audited agency financial statements.<br />

However, Treasury does not<br />

have a systematic process in place to<br />

identify the reconciling items and their<br />

source. The information is compiled<br />

by ad hoc procedures applied by<br />

Treasury’s staff, another indication of a<br />

breakdown in the compilation process<br />

used by Treasury.<br />

This chapter presents the results<br />

of our research exploring these issues<br />

along with recommendations to create<br />

an auditable process for the roll-up of<br />

reliable government-<strong>wide</strong> budgetary<br />

and other information needed to bridge<br />

the current gap.<br />

Analysis<br />

Throughout the course of our<br />

research, our inquiries consistently led<br />

us to disparities between receipts and<br />

outlays reported at the agency and at<br />

government-<strong>wide</strong> levels. Specifically,<br />

unreconciled differences exist between<br />

(1) receipts and outlays that agencies<br />

reported in their audited financial<br />

statements and (2) the receipt and<br />

outlay components of the Unified<br />

Budget Deficit derived from Treasury’s<br />

central accounting system and reported<br />

in the CFS. The likely source of these<br />

disparities is definitional and due to<br />

reporting differences between the ways<br />

budgetary information is compiled and<br />

reported at the agency and government-<strong>wide</strong><br />

levels.<br />

For example, some receipts are<br />

offset against agency outlays and<br />

reported net at the agency level, while<br />

other receipts are recorded only at<br />

the government-<strong>wide</strong> level. On the<br />

outlay side, the composition of agency<br />

budgetary accounts (Treasury Fund<br />

Symbols) used to compile the audited<br />

agency SBR may be different than the<br />

list of budget accounts used to report<br />

on the government-<strong>wide</strong> budget.<br />

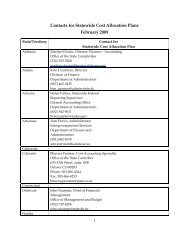

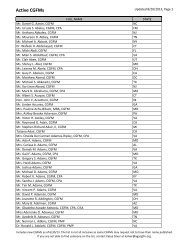

Figure 1: Net Outlay Differences for Fiscal Year 2011 at Selected<br />

Agencies Between Treasury’s Central Accounting System<br />

(as reported in the CFS) versus Audited Agency <strong>Financial</strong> Statements (as reported in agency SBRs)<br />

Selected Agencies<br />

Net Outlays<br />

(Combined Statement)<br />

Amounts in Millions<br />

Net Outlays<br />

(SBR)<br />

Difference<br />

Department of Health and Human Services $ 891,244 $ 891,532 $ (288)<br />

Social Security Administration $ 784,194 $ 784,305 $ (111)<br />

Department of Defense $ 742,990 $ 742,794 $ 196<br />

Department of Treasury $ 417,410 $ 430,701 $ (13,291)<br />

Department of Labor $ 131,973 $ 132,969 $ (996)<br />

Department of Education $ 64,271 $ 66,387 $ (2,116)<br />

Department of Homeland Security $ 45,744 $ 46,976 $ (1,232)<br />

Department of Energy $ 31,372 $ 31,350 $ 22<br />

Department of State $ 24,334 $ 26,000 $ (1,666)<br />

Total $ 3,133,532 $ 3,153,014 $ (19,482)<br />

Note: In Figure 1, “Department of Defense” includes the following categories from the Combined Statement: Defense-Military, Army<br />

Corps of Engineers and Other Defense Civil Programs.<br />

Source: Treasury’s annual Combined Statement of Receipts, Outlays and Balances of the U.S. <strong>Government</strong> (Combined Statement)<br />

and Agency <strong>Financial</strong> Statements.<br />

10<br />

<strong>AGA</strong> Corporate Partner Advisory Group Research

Breakdowns in the Compilation Process<br />

Net outlay differences are highlighted<br />

in Figure 1. Treasury’s compilation<br />

procedures do not include a<br />

process to identify, reconcile and audit<br />

these net differences, which are even<br />

greater on a gross basis.<br />

Over the past 15 years, much time<br />

and effort have been placed on improving<br />

the quality of financial information<br />

reported in both agency financial<br />

statements and the CFS. It is fair to say<br />

that the majority of the focus to date<br />

has been on the accrual basis accounts<br />

within an agency. Only one of an<br />

agency’s financial statements — the SBR<br />

— is derived solely from an agency’s<br />

budgetary accounts, which are primarily<br />

on a cash basis. Information reported<br />

in the SBR is aggregated at the agency<br />

level, and final audited numbers are not<br />

reported further to or used by Treasury.<br />

Arguably, budgetary information is the<br />

most useful financial information within<br />

an agency, yet the lack of a transparent<br />

reconciliation process between agency<br />

and government-<strong>wide</strong> balances has had<br />

the effect of inhibiting the audit of probably<br />

the most quoted and used number<br />

published by the federal government —<br />

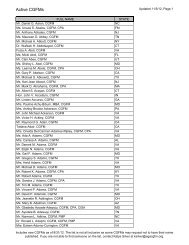

the Unified Budget Deficit.<br />

Data Flows Supporting<br />

the Compilation Process<br />

Two primary data flows of accrual<br />

and budgetary financial data support<br />

the production of the CFS — the first<br />

flow is audited, the other is unaudited.<br />

The information needed to populate the<br />

CFS reconciliation statements referred<br />

to previously is derived from a combination<br />

of accrual and budgetary data<br />

flows. In Figure 2 (page 12), the audited<br />

flow is on the left, derived from audited<br />

agency financial statements. The<br />

unaudited flow, on the right, is derived<br />

from periodic agency budget execution<br />

reports (SF-133 and SF-224) aggregated<br />

in Treasury’s central accounting system.<br />

Also derived from this flow are<br />

Treasury’s Combined Statement and the<br />

The lack of a transparent reconciliation<br />

process has inhibited the audit of probably<br />

the most quoted and used number<br />

published by the federal government—<br />

the Unified Budget Deficit.<br />

Unified Budget Deficit. The red arrows<br />

bridging the two data flows represent<br />

our recommendation to reconcile and<br />

bridge budgetary information with<br />

audited agency financial statement<br />

balances and to identify and audit any<br />

other budgetary activity reported as<br />

part of the government-<strong>wide</strong> balances in<br />

Treasury’s central accounting system.<br />

While an audit trail has been built<br />

between (1) audited agency financial<br />

statements (Statement of Net Cost,<br />

Statement of Operations and Changes<br />

in Net Position, Balance Sheet and<br />

Statement of Custodial Activity) and<br />

(2) the CFS for many accounts and<br />

line items, the audit trail has not been<br />

completed for budgetary accounts<br />

that comprise receipts and outlays. In<br />

2002, Treasury in conjunction with OMB<br />

developed the Closing Package concept<br />

for agencies to report to the FMS for its<br />

preparation of the CFS.<br />

The Closing Package is supported<br />

by the <strong>Government</strong><strong>wide</strong> <strong>Financial</strong><br />

<strong>Reporting</strong> System (GFRS), which<br />

requires agencies to input audited<br />

information from their financial statements<br />

and crosswalk that information<br />

to line items reported in the CFS. OMB<br />

and Treasury require that the agency<br />

financial statement audits extend to<br />

the agency information reported in the<br />

GFRS to provide assurance regarding<br />

the crosswalking of audited information.<br />

This process effectively leverages<br />

agency audit results for the accrual<br />

accounts and line items contained in<br />

the CFS.<br />

Taking a closer look, Figure 2 illustrates<br />

three primary flows of financial<br />

data relevant to the CFS compilation<br />

process. Two of these flows are audited,<br />

and one is unaudited.<br />

The first flow, to the left, is audited<br />

information agencies reported in<br />

the Closing Package process in the<br />

GFRS. This information is derived<br />

from audited agency financial<br />

statements and the crosswalk of<br />

data into the GFRS is also audited.<br />

<strong>Financial</strong> information flowing<br />

through this process is adequately<br />

bridged, and an audit trail exists to<br />

support the flow of information.<br />

The second flow of information, in<br />

the middle, is audited, but stops at<br />

the agency level. Agencies currently<br />

produce an SBR that includes<br />

outlay information. As the primary<br />

budgetary statement, the SBR is one<br />

of the principal financial statements<br />

that agencies produce. It is audited<br />

as part of the annual agency financial<br />

audit but is not included in the<br />

Closing Package or the GFRS and is<br />

not used in compiling the CFS.<br />

The third flow of data is unaudited<br />

gross receipts and outlays reported<br />

by agencies in periodic reports to<br />

Treasury and transmitted via the<br />

FACTS II system. 15 These reports<br />

include the Report on Budget<br />

<strong>Government</strong>-<strong>wide</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Reporting</strong> 11

Breakdowns in the Compilation Process<br />

Figure 2: Data Flows Supporting the <strong>Government</strong>-<strong>wide</strong> CFS<br />

Agency Level <strong>Government</strong>-<strong>wide</strong><br />

Level<br />

Accrual Balances<br />

Audited<br />

Audited balances,<br />

crosswalked and<br />

transmitted via the<br />

Closing Package/<br />

GFRS process<br />

<strong>Government</strong>-<strong>wide</strong> Consolidated <strong>Financial</strong> Statements (CFS)<br />

Audited Agency<br />

<strong>Financial</strong> Statements<br />

- Balance Sheet<br />

- Statement of<br />

Net Cost<br />

- Statement of<br />

Changes in Net<br />

Position<br />

Budgetary Balances<br />

Audited<br />

Audited balances<br />

in SBR are not<br />

crosswalked or<br />

transmitted in<br />

preparing the CFS<br />

Audited Net Outlay and<br />

Receipt Balances *<br />

- Agency Statement of<br />

Budgetary Resources<br />

(SBR)<br />

- Statement of<br />

Custodial Activity<br />

Budgetary Balances<br />

Unaudited<br />

Recommended twostep<br />

reconciliation,<br />

reporting, and audit<br />

process<br />

Treasury Central<br />

Accounting System<br />

- Gross receipts<br />

- Gross outlays<br />

Transmitted via<br />

FACTS II system<br />

Receipts and Outlays<br />

Reported to Treasury<br />

Periodically<br />

(from SF-133 and<br />

SF-224 reports)<br />

Combined Statement<br />

of Receipts, Outlays,<br />

Balances<br />

Unified<br />

Budget<br />

Deficit<br />

Agency General Ledger<br />

= Unaudited<br />

= Audited<br />

= Red arrows denote recommended two-step reconciliation, reporting and audit<br />

processes. First, a reconciliation of agency to Treasury receipts and outlays, and<br />

second, the reporting of significant components of differences between the Unified<br />

Budget Deficit and Net Operating Cost and the change in cash. All information<br />

would be transmitted through the Closing Package process, subjecting it to audit.<br />

* Including receipts reported as Earned Revenue on the Statement of Net Cost<br />

Note: The recommendations in red are intended only to address the compilation process weakness. Other weaknesses reported by<br />

GAO related to intragovernmental activity and DoD financial management would need to be separately resolved.<br />

12<br />

<strong>AGA</strong> Corporate Partner Advisory Group Research

Breakdowns in the Compilation Process<br />

Execution and Budgetary Resources<br />

(SF-133) and the Statement of<br />

Transactions (SF-224). They are<br />

entered into Treasury’s central<br />

accounting system, which is used<br />

to compile the CFS, and eventually<br />

generate the Unified Budget Deficit<br />

reported by Treasury.<br />

Also derived from this flow is the<br />

Combined Statement, 16 a report FMS<br />

issues annually, usually in December.<br />

<strong>Financial</strong> data flowing through this<br />

process is not reconciled to audited<br />

budgetary information reported by<br />

agencies in either the SBR or to revenue<br />

in the Statement of Custodial Activity,<br />

through which many agencies report<br />

significant receipts such as tax collections<br />

by the Internal Revenue Service<br />

or mineral/oil royalties collected by<br />

the Department of the Interior. While<br />

budgetary information reported in the<br />

SBR and periodic reports to Treasury,<br />

such as the SF-133 and SF-224, are reconciled<br />

at the agency level, a complete<br />

reconciliation to information contained<br />

in Treasury’s central accounting system<br />

is not performed as part of the compilation<br />

process.<br />

Taking the steps necessary to establish<br />

a complete foundation of audited<br />

information from which the balances<br />

in the CFS are derived is a prerequisite<br />

for fully addressing the current gaps in<br />

the compilation process. This entails<br />

addressing two primary gaps in the process:<br />

first, the gap between agency and<br />

government-<strong>wide</strong> budgetary information,<br />

and second, the gap between the<br />

Unified Budget Deficit, Net Operating<br />

Cost and the changes in cash.<br />

Bridging Unaudited<br />

Budgetary Information to<br />

Audited Balances<br />

Building a reconciliation process<br />

that bridges unaudited and audited<br />

budgetary information is a solution we<br />

heard in a number of our interviews.<br />

This would establish a transparent<br />

audit trail and complete foundation of<br />

audited accrual and budgetary information<br />

from which the CFS is compiled. It<br />

is clear that Treasury understands the<br />

nature of many of the differences that<br />

exist related to budgetary information<br />

between agencies and the government<strong>wide</strong><br />

balances reported in the CFS.<br />

Treasury has analyzed many of the<br />

receipt and outlay differences and has<br />

significant insight into the areas as<br />

well as into specific agencies where<br />

underlying definitional and reporting<br />

differences exist.<br />

We were briefed on a number of<br />

past initiatives to build this bridge and<br />

design a process to reconcile budgetary<br />

information as well as document<br />

an audit trail between agency and CFS<br />

budgetary data. These past efforts<br />

have provided significant insight into<br />

the problem and have made it easier to<br />

pinpoint potential troublesome areas.<br />

For example, Treasury described reconciliation<br />

approaches for receipts at the<br />

Internal Revenue Service and at Interior.<br />

From both of these efforts, considerable<br />

insight was gained and can be leveraged<br />

to develop a standard reconciliation<br />

template for receipts and outlays.<br />

Further contributing to the gap<br />

between agency and CFS budgetary<br />

information is the form and content<br />

of the agency financial statements as<br />

compared to the CFS and the ease with<br />

which accrual and budgetary information<br />

reported at the agency level aligns<br />

with similar information reported at<br />

the CFS level. For example, agency<br />

Balance Sheets and Statements of Net<br />

Cost align closely with the CFS Balance<br />

Sheet and Statement of Net Cost, so<br />

it is easier to link agency information<br />

to CFS information. Similar alignment<br />

with budgetary accounts and the SBRs<br />

at the agency and CFS levels does not<br />

currently exist. For example, the SBR<br />

does not align with similar statements<br />

at the CFS level.<br />

Identifying and <strong>Reporting</strong><br />

the Differences Between<br />

the Unified Budget Deficit,<br />

Net Operating Cost and the<br />

Changes in Cash Needed<br />

to Populate the CFS<br />

Reconciliation Statements<br />

The discussed alignment issue<br />

extends to other statements compiled<br />

only at the government-<strong>wide</strong> level.<br />

The CFS contains two financial statements,<br />

which are reconcilable in nature<br />

and identify the major differences<br />

between the Unified Budget Deficit, Net<br />

Operating Cost and the changes in cash<br />

at the government-<strong>wide</strong> level. Unlike<br />

other financial statements in the CFS,<br />

such as the Balance Sheet or Statement<br />

of Net Cost, these statements are not<br />

closely aligned with audited agencylevel<br />

financial statements. These alignment<br />

issues make these statements<br />

particularly challenging to produce.<br />

Since Unified Budget Deficit is<br />

reported in both statements, it is<br />

critical as a first step that the receipts<br />

and outlays comprising these two<br />

important totals first be reconciled to<br />

audited balances. While some level of<br />

Treasury analysis will always be needed<br />

to review and compile the line items on<br />

the two reconciliation statements, the<br />

compilation of the reconciliation statements<br />

is not supported by a reliable<br />

and documented compilation process.<br />

In concept, the gap in the compilation<br />

process related to these statements<br />

is no different from the gap identified<br />

related to receipts and outlays. In both<br />

cases, CFS balances are not linked<br />

back to audited information reported in<br />

audited agency financial statements or<br />

to reconciling information identified as<br />

part of the Closing Package process and<br />

separately audited. Historically, both<br />

reconciliation statements have been<br />

compiled based on analysis performed<br />

at Treasury level or by audit adjustments<br />

identified by GAO.<br />

<strong>Government</strong>-<strong>wide</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Reporting</strong> 13

Breakdowns in the Compilation Process<br />

Our recommendation is intended to provide<br />

a full accounting of gross receipts and outlays<br />

comprising the Unified Budget Deficit.<br />

Treasury is aware of most of the<br />

reconciling items needed to populate the<br />

CFS reconciliation statements as a result<br />

of experience gained in compiling the CFS<br />

over the years. Treasury has a detailed<br />

understanding of these items and the<br />

activities underlying the differences.<br />

But, as we have seen with the Troubled<br />

Asset Relief Program (TARP) and other<br />

newly implemented programs, new items<br />

can be created each year by legislation<br />

or new/revised policies. Developing a<br />

systematic process to identify and report<br />

these reconciling items can be built on the<br />

foundation that already exists and can be<br />

enhanced by improved communication<br />

between Treasury and the agencies. The<br />

result would be needed improvements in<br />

the compilation process.<br />

A Related Initiative<br />

The <strong>Government</strong><strong>wide</strong> Treasury<br />

Account Symbol Adjusted Trial Balance<br />

System (GTAS) initiative was brought to<br />

our attention. GTAS is intended to validate<br />

both budgetary and accrual-based<br />

information reported by agencies and<br />

to facilitate the analysis of government<strong>wide</strong><br />

spending. GTAS, now under development,<br />

could improve the integrity of<br />

budgetary data and facilitate a solution<br />

to reconciling reported differences since<br />

information should be more reliable.<br />

GTAS is similar to the FACTS II<br />

process in design. Scheduled to go<br />

into production in December 2012,<br />

the system is expected to improve<br />

the integrity of all types of financial<br />

information agencies report. As GTAS<br />

becomes more advanced, agencies will<br />

be required to pass more edit checks<br />

before their data can be submitted<br />

to Treasury. These edit checks are<br />

expected to include tests to validate<br />

the relationship between budgetary<br />

and accrual data and the completeness<br />

of adjusting entries. In concept,<br />

higher quality underlying agency data<br />

will enable the production of better<br />

quality financial statements at both the<br />

agency and government-<strong>wide</strong> levels<br />

because the underlying database will<br />

be the same at agencies and in GTAS.<br />

Pilot efforts are under way to reconcile<br />

agency trial balances reported in the<br />

GTAS to agency financial statements.<br />

GTAS is not intended to be a shortterm<br />

or long-term solution to GAO<br />

findings related to the compilation of<br />

the CFS. GTAS is not a substitute for a<br />

compilation process built from audited<br />

agency financial statements, which<br />

is the concept underlying the Closing<br />

Package approach.<br />

Our recommendations acknowledge<br />

Treasury’s success in linking audited<br />

agency accrual data to the CFS using the<br />

Closing Package approach. We seek to<br />

leverage that success to reconcile budgetary<br />

data through a similar reporting,<br />

reconciliation and audit process.<br />

Short-Term<br />

Recommendations<br />

Recommendation 2.1: Continue to<br />

use and enhance the Closing Package<br />

process in compiling the CFS to include<br />

the reconciliation and audit of budgetary<br />

data and the items needed to<br />

prepare the reconciliation statements.<br />

The Closing Package process and<br />

the approach of deriving reliable<br />

government-<strong>wide</strong> information from<br />

audited agency financial statements is<br />

a transparent and auditable compilation<br />

process for the overwhelming majority<br />

of the balances in the CFS. In an entity<br />

the size of the federal government with<br />

agencies larger and more complex than<br />

many states and international corporations,<br />

accountability, data reliability and<br />

credibility should always be based on<br />

audited financial statements. Building<br />

on the foundation of audited agency<br />

information is a critical component of a<br />

sound, reliable compilation process.<br />

The existing Closing Package/GFRS<br />

process provides a solution that has<br />

been proven successful in establishing<br />

an audit trail between audited agency<br />

financial statements and the CFS. The<br />

current compilation process used for<br />

accrual balances that leverages audited<br />

agency financial statements through the<br />

Closing Package process has allowed<br />

Treasury to approach a transparent<br />

and auditable compilation process. By<br />

extending this process to include the<br />

reconciliation and audit of budgetary<br />

data as well as the accumulation of<br />

information needed to prepare the reconciliation<br />

statements, Treasury will be<br />

within striking distance of a reliable and<br />

auditable overall compilation process.<br />

Recommendation 2.2: Establish a<br />

process to reconcile and audit budgetary<br />

information reported in audited agency<br />

financial statements with gross receipt<br />

and outlay cash flows in Treasury’s<br />

central accounting system. To facilitate<br />

a complete reconciliation, Treasury<br />

should provide agencies with a populated<br />

reconciliation template as a starting point.<br />

Additional agency procedures are required<br />

to periodically perform the reconciliation,<br />

given that the detailed information to successfully<br />

identify and resolve differences<br />

exists at the agency level.<br />

This recommendation is intended<br />

to provide a full accounting of gross<br />

receipts and outlays reported in the CFS<br />

comprising the Unified Budget Deficit.<br />

Agency budgetary information is compiled,<br />

reported periodically to Treasury<br />

and audited in aggregate annually in the<br />

14<br />

<strong>AGA</strong> Corporate Partner Advisory Group Research

Breakdowns in the Compilation Process<br />

SBR. However, budgetary information<br />

reported in the CFS is independently<br />

generated from Treasury’s central<br />

accounting system. A process should<br />

be established to reconcile receipts<br />

and outlay information between these<br />

independent sources. Treasury has<br />

attempted to perform this reconciliation<br />

as part of the annual compilation<br />

process and on an agency pilot basis<br />

without broad success. However, in<br />

defense of Treasury’s efforts, the time,<br />

resources and level of detail do not<br />

exist at Treasury to successfully perform<br />

this reconciliation for each agency.<br />

Agencies must “own” their data and, in<br />

turn, “own” the reconciliation process.<br />

The reconciliation process should<br />

be facilitated by Treasury through the<br />

identification of Treasury Fund Symbols<br />

and receipt accounts that are tagged to<br />

agency balances in Treasury’s central<br />

accounting system that can be used by<br />

agencies to make similar comparisons<br />

of the Treasury Fund Symbols included<br />

in their SBRs. Similar comparisons of<br />

the composition of receipt accounts<br />

should also be made. A populated standard<br />

reconciliation template, provided<br />

quarterly by Treasury to each agency,<br />

can serve as a starting point for the<br />

reconciliation. The detailed reconciliation<br />

must be performed at the agency<br />

level where the information exists for<br />

the agency to successfully identify<br />

and resolve definitional and reporting<br />

differences. A budgetary reconciliation<br />

process will add transparency to differences<br />

in budgetary balances reported<br />

in the CFS and establish an audit trail<br />

from audited agency reported budgetary<br />

information to similarly aggregated<br />

information reported at the CFS level.<br />

In addition, performing this quarterly<br />

reconciliation will facilitate the proactive<br />

identification and resolution of differences<br />

and enhance the reliability and<br />

timely compilation to meet stringent CFS<br />

production and audit timelines at year<br />

end. It is important to note that controls<br />

exist at most agencies to reconcile<br />

the annual audited SBR and the actual<br />

column of the President’s Budget. This<br />

process should be leveraged to the<br />

extent possible in performing this reconciliation.<br />

However, this reconciliation<br />

does not always include all receipt and<br />

outlay accounts as a starting point and<br />

may not include final budgetary balances<br />

because of timing differences between<br />

the CFS and the President’s Budget.<br />

Recommendation 2.3: Establish a<br />

process to identify, report and audit the<br />

major differences between the Unified<br />

Budget Deficit, Net Operating Cost and<br />

the changes in cash government-<strong>wide</strong><br />

to populate the CFS reconciliation<br />

statements. To facilitate this process,<br />

Treasury should consider providing<br />

agencies with a reconciliation template<br />

populated by using the relevant line<br />

items on the current reconciliation statements<br />

as part of the Closing Package.<br />

This recommendation is intended<br />

to provide Treasury with a systematic<br />

process to accumulate and support<br />

the information it uses to populate<br />

the reconciliation statements. The<br />

information needed to populate the<br />

“Reconciliation of Net Operating Costs<br />

and Unified Budget Deficit” comes from<br />

a combination of agency-supplied data<br />

and Treasury-maintained data. Audited<br />

agency information should be collected<br />

through the Closing Package process<br />

and leveraged to the extent possible<br />

(see Recommendation 2.4).<br />

The information needed to populate<br />

the Statement of Changes in Cash<br />

Balance will likely reside at Treasury, but<br />

to the extent that information is needed<br />

from the agencies, a second template<br />

should be developed to obtain the information.<br />

Many agencies will only populate<br />

a few line items on the template(s), but it<br />

is each agency’s responsibility to identify<br />

the applicable line items. To ensure<br />

consistency in reporting, the template(s)<br />

should be supplemented with guidance<br />

describing precisely what is to be<br />

included on each line. Treasury’s process<br />

should include a mechanism to enable<br />

Treasury to identify and quantify reconciling<br />

items that result from new or revised<br />

policies or legislation. As with the process<br />

recommended for budgetary data in<br />

Recommendation 2.2, this process would<br />

provide a transparent, documented trail<br />

of audited data supporting CFS budgetary<br />

versus GAAP differences.<br />

Recommendation 2.4: Include<br />

budgetary information and information<br />

needed to prepare the reconciliation<br />

statements in the Closing Package<br />

process and the GFRS to provide<br />

transparency and full audit coverage<br />

of budgetary receipts, outlays and<br />

differences between the Unified Budget<br />

Deficit, Net Operating Cost and changes<br />

in cash government-<strong>wide</strong>. The Closing<br />

Package submission should clearly<br />

identify those budgetary balances<br />

and reconciling items derived from<br />

audited agency financial statements<br />

and any other balances or reconciling<br />

items that need to be addressed at the<br />

government-<strong>wide</strong> level.<br />

While Recommendation 2.2<br />

describes a process and audit trail<br />

for budgetary information and<br />

Recommendation 2.3 suggests a<br />

process for accumulating reconciling<br />

items, Recommendation 2.4 is intended<br />

to add rigor by subjecting to audit the<br />

crosswalking of reconciled receipts,<br />

outlays and reconciling items as part<br />

of the Closing Package process. As<br />

discussed, the Closing Package process<br />

has facilitated the linkage of audited<br />

agency-level accrual basis information<br />

to the CFS. Thus, an established audit<br />

trail and reporting process exists for<br />

accrual account balances from agency<br />

financial statements to the CFS. We<br />

recommend that the results of the budgetary<br />

reconciliation be incorporated<br />

into the Closing Package process and the<br />

GFRS to essentially crosswalk audited<br />

agency-level budgetary balances to<br />

budgetary balances included in the CFS,<br />

including the Unified Budget Deficit<br />

balance. By including in the Closing<br />

Package the items needed to populate<br />

<strong>Government</strong>-<strong>wide</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Reporting</strong> 15

Breakdowns in the Compilation Process<br />

the reconciliation statements, these<br />

items will be subject to the same audit<br />

procedures as the accrual account balances<br />

currently included in the Closing<br />

Package.<br />

No similar linkage exists for budgetary<br />

information, namely gross receipts<br />

and outlays comprising the Unified<br />

Budget Deficit balance and items<br />

needed to populate the reconciliation<br />

statements. Some of this information<br />

may not be reported in agency<br />

financial statements, and therefore are<br />

not subject to audit. Presenting other<br />

financial information to Treasury as part<br />

of the Closing Package will facilitate<br />

the collection and audit of a complete<br />

accounting of receipts, outlays and<br />

reconciling items.<br />

Recommendation 2.5: Compile the<br />

CFS at the end of the third quarter to<br />

improve internal controls surrounding<br />

the Closing Package process and facilitate<br />

meeting the December 15 reporting<br />

deadline.<br />

Even if all of these process improvement<br />

recommendations are implemented,<br />

the compilation process must start earlier<br />

in the year and include a “trial run” at the<br />

end of the third quarter to reduce financial<br />

reporting and audit risk. This leading<br />

practice has been <strong>wide</strong>ly implemented<br />

by the government and private sector.<br />

For example, all publicly held companies<br />

undergo a hard close at least quarterly,<br />

with reports to the SEC.<br />

Federal agencies formerly prepared<br />

financial statements only at year end.<br />

Under this process, agencies produced<br />

audited financial statements six or more<br />

months after year end using costly<br />

and “heroic” efforts, not a process<br />

that could be described as disciplined,<br />

routine or reliable.<br />

Accelerated agency financial reporting<br />

transformed this process to one<br />

where auditors and management now<br />

start earlier in the year to implement,<br />

test and gain confidence in financial<br />

reporting processes and controls. This<br />

enables year-end reporting to be more<br />

routine and reliable. This same transformation<br />

must occur in the process<br />

surrounding the compilation of the CFS.<br />

Performing a hard close at the end of<br />

the third quarter, using agency financial<br />

statements to populate an interim<br />

Closing Package and working with auditors<br />

to perform interim procedures is<br />

essential to routinely producing reliable<br />

and timely audited, government-<strong>wide</strong><br />

financial statements by mid-December.<br />

Long-Term<br />

Recommendation<br />

Recommendation 2.6: Continue<br />

to pursue and assess the feasibility,<br />

costs and benefits of a more centralized<br />

approach to standardizing, collecting,<br />

analyzing and reporting financial<br />

information.<br />

Over the longer term, technology<br />

will continue to drive greater capability<br />

and provide additional automated<br />

options. As has been the case with<br />

the evolution of agency-level financial<br />

reporting systems, manual processes<br />

and compensating controls have been<br />

replaced by more automated and<br />

reliable financial systems. This recommendation<br />

addresses these longer-term<br />

considerations.<br />

We also recognize the value of<br />

standardized government-<strong>wide</strong> data,<br />

processes and controls as a potential<br />

longer-term initiative from which<br />

reliable financial reports could emerge.<br />

This could facilitate the collection<br />

of government-<strong>wide</strong> data that could<br />

then be analyzed and easily accessed.<br />

Treasury should continue to pursue and<br />

assess the costs and related benefits of<br />

centralized accounting options.<br />

16<br />

<strong>AGA</strong> Corporate Partner Advisory Group Research

3. Usefulness of the Two CFS<br />

Reconciliation Statements<br />

Issue<br />

As discussed previously, included in<br />

the material weakness cited by GAO is a<br />

breakdown in the compilation processes<br />

related to the two budgetary statements<br />

included only in the CFS — Reconciliation<br />

of Net Operating Cost and Unified Budget<br />

Deficit (Reconciliation Statement) and<br />

Statement of Changes in Cash Balance<br />

for Unified Budget and Other Activities<br />

(Statement of Changes in Cash). When<br />

reconciled to the consolidated net<br />

operating cost on an accrual basis and to<br />

changes in cash, the information regarding<br />

the Unified Budget Deficit provides a<br />

unique perspective available only at the<br />

consolidated federal government level.<br />

During the course of our research, we<br />

assessed the utility of this information<br />

and whether any changes in reporting<br />

should be considered.<br />

As stated in Chapter 2, the form and<br />

content of the CFS does not fully align<br />

with audited agency financial statements.<br />

In some cases, such as with the Balance<br />

Sheet and Statement of Net Cost, alignment<br />

is fairly close, so balances can be<br />

crosswalked through the Closing Package<br />

process fairly easily to balances in statements<br />

appearing in the CFS. However, for<br />

the Reconciliation of Net Operating Cost<br />

and Unified Budget Deficit (Reconciliation<br />

Statement) and Statement of Changes<br />

in Cash Balance for Unified Budget and<br />

Other Activities (Statement of Changes<br />

in Cash), no comparable statement exists<br />

at the agency level. Agencies prepare a<br />

footnote reconciling Net Cost to obligations<br />

that have some similarities and may<br />

crosswalk to some line items in the CFS.<br />

No analog for the Statement of Changes<br />

in Cash exists at the agency level. The<br />

unique nature of these two CFS “reconciliation”<br />

statements presents compilation<br />

challenges and complexities for Treasury.<br />

While these challenges can be overcome,<br />

as discussed in Chapter 2, our intent is to<br />

draw attention to this lack of alignment,<br />

assess the utility of this information, and<br />

address whether any changes in reporting<br />

should be considered.<br />

Reconciliation of Net Cost<br />

Is a Critical <strong>Financial</strong><br />

Statement Within the CFS<br />

Reconciling the difference between<br />

consolidated net operating costs calculated<br />

on an accrual basis to the Unified<br />

Budget Deficit provides users with<br />

each perspective — both accrual and<br />