SPrIng - WERC

SPrIng - WERC

SPrIng - WERC

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Spring 2012<br />

WAREHOUSING EDUCATION AND RESEARCH COUNCIL<br />

THE ASSOCIATION FOR LOGISTICS PROFESSIONALS<br />

Watch<br />

A Periodic Assessment<br />

of Industry Trends<br />

Provided by and for the Warehousing Professional<br />

Findings of a survey of benchmarking measures among <strong>WERC</strong> members and DC Velocity readers.<br />

DC Measures 2012<br />

by<br />

Karl B. Manrodt, PhD<br />

Professor<br />

Georgia Southern University<br />

Kate L. Vitasek<br />

Managing Partner<br />

Supply Chain Visions<br />

Joseph M. Tillman<br />

Senior Researcher<br />

Supply Chain Visions<br />

Senior Management Interest in Performance Measures<br />

We are continually pleased with the interest in the metrics<br />

survey. In part, we believe that it is due to senior executives’<br />

interest in how well their supply chain is performing relative<br />

to everyone else. One of the annual questions asks about the<br />

level of interest in measures on the part of senior management.<br />

The results show that almost 96% of respondents say their<br />

executives’ interest in performance is not waning.<br />

Over the past few years, we have noticed senior<br />

management’s interest in measures hit a plateau. Growth<br />

in the number of senior executives reported as having an<br />

increasing interest in measures slowly declined starting<br />

with the 2008 study. This year is the first time in four years<br />

the percentage of senior executives reported an increased<br />

interest in measures (Figure 1). We believe this increase can<br />

be attributed to a couple of factors. First, as the economy<br />

improves it will become necessary to better understand if<br />

goals are being met. > pg. 2<br />

About the Study<br />

2012 is the ninth year of the Warehouse Education and<br />

Research Council (<strong>WERC</strong>) and DC Velocity’s annual<br />

warehouse benchmarking study, “DC Measures.”<br />

As in previous years, the study results and analysis are<br />

complied and presented by our partners at Georgia<br />

Southern University and Supply Chain Visions, two widely<br />

respected organizations in the area of performance<br />

management and measurement.<br />

The heart of this study is to help practitioners gain a<br />

better understanding of key distribution metrics and<br />

report how performance has changed over time. Over<br />

the years the study has focused in on various themes; for<br />

instance, highlighting the importance of the perfect order,<br />

tracking significant changes in measures, comparing<br />

bad warehouses to good warehouses and a Seven Step<br />

process for Benchmarking. This year we want to challenge<br />

practitioners to rethink their performance scorecards.<br />

Rather than focus only on operational performance and<br />

view supply chains solely as purely logical or mechanical<br />

systems, they should start measuring both the hard and<br />

soft sides of performance if they want to truly gauge their<br />

supply chain success.<br />

This survey was launched via an email invitation to <strong>WERC</strong><br />

members and DC Velocity readers in early January<br />

2012. Survey participants are asked to report their actual<br />

levels of performance for 2011. The study captures 44 key<br />

operational metrics that are close to the heart of most<br />

distribution center professionals. The measures have been<br />

grouped into 5 balanced sets —customer, operational,<br />

financial, capacity/quality and employee —plus the<br />

additional sets related to perfect order and cash-to-cash<br />

cycle measurement.<br />

Warehousing education and research council • 1100 Jorie blvd, ste 170, Oak Brook, IL 60523-4413<br />

P | 630.990.0001 F | 630.990.0256 E | wercoffice@werc.org W | www.werc.org

Figure 1. Interest in measures on part of<br />

senior management for 2012<br />

Decreasing 4.2%<br />

Increasing<br />

59.2%<br />

Staying the<br />

Same<br />

36.6%<br />

Figure 3. Respondents by Industry<br />

Other 3.5%<br />

Transportation<br />

Service Provider 1.4%<br />

Third-party<br />

Warehouse<br />

25.2%<br />

Utilities/Government<br />

1.4%<br />

Food Distribution<br />

2.1% Wholesale<br />

Distribution<br />

7.7%<br />

Retail<br />

16.1%<br />

Manufacturing<br />

35%<br />

Second, as warehouses and DCs prepare for growth, or for the<br />

next economic crisis, their scorecards will need to go beyond<br />

operational metrics. Developing relationships with your suppliers<br />

is quickly becoming an important aspect for warehouses and DCs<br />

to succeed in this rapidly changing economic environment. In<br />

order to capture a true picture of success, facilities will need to<br />

begin measuring the softer side of performance.<br />

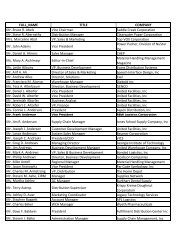

Respondents Represent Diverse Industries, Operations<br />

and Firm Sizes<br />

The number of responses was relatively large for this year<br />

(in excess of 225 for 2012). However, it did not match last<br />

year’s usable responses. In order to increase the predictive<br />

power of the benchmarks, 2012 results were combined with<br />

2011 results. Analysis was completed and verified that the<br />

results were statistically similar. Therefore, over the two-year<br />

period, 802 individuals responded to the survey. The largest<br />

group of respondents reported their title as Manager (50.7%),<br />

while Director (27.5%) and Senior VP (14.1%) were the second<br />

Figure 2. Respondent Titles<br />

CEO/President 3.5%<br />

Manager<br />

50.7%<br />

Other 4.2%<br />

Senior VP<br />

14.1%<br />

Director<br />

27.5%<br />

Life Sciences –<br />

Medical Devices<br />

4.2%<br />

and third largest groups. Executives represent 3.5%. Figure 2<br />

provides a breakdown of the survey respondents’ titles.<br />

In addition to understanding who participated in the study,<br />

we reviewed five unique demographic areas, including:<br />

1. Type of industry<br />

2. Type of operation<br />

3. Type of customer<br />

4. Business strategy<br />

5. Size of company<br />

Demographics by Industry Type<br />

Figure 3 provides a breakdown of the various business<br />

segments that participated in the study. As with previous<br />

years, the manufacturing industry segment remains the largest<br />

demographic base for the study. However, a continued increase<br />

in participation by third party warehouses is good news as this<br />

reflects how diverse the industry has become.<br />

Because the manufacturing segment is so large, a further<br />

breakdown and explanation of the types of industries falling<br />

under the manufacturing segment is shown in Table 1.<br />

Table 1. Manufacturing Industry Breakdown<br />

Business Segment<br />

Manufacturing<br />

Life Sciences –<br />

Pharmaceuticals 3.5%<br />

Further Industry<br />

Breakdown<br />

Percent<br />

Consumer Products 19.6%<br />

High Technology 4.2%<br />

Automotive 1.4%<br />

General 9.8%<br />

2<br />

®<br />

Watch<br />

SPRING 2012

Table 2. Respondents by DC Operation<br />

Metric % of Total % Cases vs. Pallet<br />

Broken Case Picking 36.9%<br />

Full Case Picking 33.4%<br />

Partial Pallet Picking 11.9%<br />

Full Pallet Picking 17.8%<br />

70.3%<br />

29.7%<br />

Demographics by DC Operation<br />

In addition to industry, respondents were asked how goods<br />

moved through their DC. As shown in Table 2, the majority of<br />

facilities (70.3%) are picking cases rather than pallets.<br />

In calculating percentages for the type of work performed,<br />

we only used responses where majority of the respondents’<br />

activity was in one of the four classifications.<br />

Compared to 2011, respondents categorized as primarily a pallet<br />

picking operation continued to decline this year. Most of the<br />

decrease was from respondents categorized as a full pallet<br />

picking operation. Over the past four years respondents primarily<br />

operating a DC utilizing full case picking have increased each<br />

year. While case picking is at its highest level in four years (70.3%)<br />

it is not as large as the 72.7% reported back in 2008.<br />

These operational fluctuations did not impact a critical<br />

distribution metric: inventory turns. Inventory turns increased<br />

from 2011 to 2012 for median and best-in-class. Inventory turns<br />

at the median increased from 10.1 turns in 2011 to 10.4 turns.<br />

Best-in-class increased from 20.3 in 2011 to 26.3 in 2012.<br />

Type of Customer Served<br />

Another important consideration is the location of the company<br />

within the supply chain. We were curious to learn if companies<br />

that are upstream suppliers used a similar set of measures to that<br />

of their customers or their customers’ customers. Respondents<br />

were asked to classify who their primary customers were in the<br />

supply chain (Figure 4).<br />

As seen in previous studies, the majority of respondents reported<br />

that they were either at or near the end of the supply chain. This<br />

year is no exception in that 50% of respondents reported their<br />

customers were either an end consumer or a retail firm.<br />

Business Strategy<br />

The fourth demographic area is business strategy and it is<br />

another area that some suggest could impact measures in this<br />

year’s survey. Do different strategies place a higher emphasis<br />

on some measures and not on others And at what level in the<br />

organization can these differences be seen or noticed<br />

To answer these questions, we asked respondents to indicate<br />

the overall business strategy for their business unit or division<br />

with respect to cost leadership, customer service, innovation or<br />

simply being all things to all people (Figure 5).<br />

Figure 4. Respondents by Type of Customer<br />

Manufacturer 16.9%<br />

Figure 5. Respondents by business strategy<br />

Cost Leadership 12%<br />

End<br />

Consumer<br />

19%<br />

Retail Firm<br />

31%<br />

Distributor/<br />

Wholesaler<br />

33.1%<br />

Mix: Be All<br />

Things to<br />

All People<br />

40.1% Customer<br />

Service<br />

38.7%<br />

Product/Market<br />

Innovation 9.2%<br />

Watch<br />

SPRING 2012<br />

3

Once again respondents report their desire to “be everything to<br />

everybody.” Since 2007, when a shift from Customer Service to the<br />

Mix strategy was first mentioned, respondents have consistently<br />

reported the Mix strategy, “be all things to all people,” as the<br />

number one strategy for DCs and warehouses. However, the Mix<br />

strategy did decrease slightly from 41.9% in 2011.<br />

Which strategy did respondents move away from Product/<br />

Market Innovation slightly lost ground, but overall there are no<br />

definitive movements from one strategy to another. For example,<br />

cost leadership and customer service slightly increased from<br />

11.4% and 37.2% in 2011. We believe these slight changes are<br />

related to warehouses and DCs fine tuning their strategies<br />

during a disruptive economic cycle.<br />

This development will be interesting to watch. We believe once<br />

the economy stabilizes and begins to improve more respondents<br />

will revert course and focus their attention back to “being all<br />

things to all people.”<br />

Respondents were also asked about their operational<br />

management strategy with respect to outsourcing. Respondents<br />

were asked whether their global, domestic and regional<br />

operations were managed internally or by a third party (Table 3).<br />

companies reporting annual sales between $100 million and<br />

$1 billion represent 39.3% of the respondents. As seen in our<br />

previous studies, we continue to have a good representation<br />

of the industry.<br />

Because we continue to have a good representation by<br />

company size, we can compare performance and determine<br />

whether larger size companies perform better than smaller<br />

companies on various metrics.<br />

Table 3. How DCs Are Managed<br />

Who Provided Responses<br />

Percent<br />

Solely 3PL Results 14.7%<br />

Mix of Both 3PL and Internal Results 14.1%<br />

Solely Internal Results 71.2%<br />

Demographics by Company Size<br />

Each year respondents indicate the relative size of their company<br />

by using annual sales. The purpose of this question is to help<br />

determine what effect size has on the kinds and number of<br />

metrics used, in addition to creating additional benchmarks<br />

based on size (Figure 6).<br />

Location, Location, Location<br />

For the past few years we have had continuing interest in the<br />

benchmarking study from respondents operating outside of the<br />

North American continent.<br />

This naturally leads us to want to make comparisons based on<br />

location as well. In our second attempt to identify those countries<br />

where we have respondents, we noticed an increasing interest<br />

from respondents outside North America. As more warehouses<br />

and DC s outside of North America continue to report their findings,<br />

we will be able to provide statistically viable benchmarks based on<br />

location. This year just over 90% of the respondents reported North<br />

America as their location, while the remaining 9.6% respondents<br />

are from countries outside of North America (Figure 7).”<br />

Figure 6. Respondents by Company Size<br />

Figure 7. Your Warehouse’s location<br />

> $1 BILLION<br />

$100 MILLION – $1 BILLION<br />

< $100 MILLION<br />

31.1%<br />

39.3%<br />

29.6%<br />

EEA 1.4% Oceania 1.4%<br />

Asia 4.8%<br />

Middle East/Africa<br />

0.7% Europe – Not EEA 0.7%<br />

0% 10% 20% 30% 40%<br />

Once again, we are pleased to see that companies of all<br />

sizes are participating in the study supporting our philosophy<br />

that companies should benchmark and focus on their<br />

performance regardless of their size. Companies with annual<br />

sales less than $100 million comprised 29.6% of our total<br />

respondents, while participants having greater than $1 billion<br />

in annual sales comprise 31.1% of the respondents. Those<br />

North America<br />

90.4%<br />

4<br />

®<br />

Watch<br />

SPRING 2012

Answering the Big Question<br />

It is a question we hear all of the time. “Our industry is unique.”<br />

“We’re different.” “We’re special.” “Your metrics don’t apply<br />

to us because…”<br />

The list goes on, but here is the quick answer. In the majority<br />

of cases, when it comes to DC performance, we don’t see<br />

statistically significant differences between firms based on any<br />

of the demographics listed above. Quantitative performance<br />

is quantitative performance. Are there differences No doubt.<br />

These differences are primarily qualitative in nature. This is<br />

why we’ve stressed using both quantitative and qualitative<br />

benchmarking.<br />

Some of you may disagree. If so, here is some good news.<br />

You can benchmark your performance on each of the metrics<br />

online at www.werc.org and compare yourself to each of<br />

the demographics listed above. In other words, if you’d like to<br />

compare yourself to other firms with less than one hundred<br />

million dollars in sales, you can do so. You can also compare<br />

yourself to the entire set of findings as well.<br />

Interpreting the Benchmarking Results<br />

A primary objective for this study is to provide a benchmark of<br />

key measures by industry and type of business and to see how<br />

these benchmarks are changing (if at all) over time.<br />

As in previous benchmark studies, we primarily looked at<br />

two benchmarks: median performance and best practice<br />

performance. We chose the median as it is not easily swayed<br />

by outliers. The benchmarking data is reported using a “quintile”<br />

format which presents the data on a five-point maturity scale<br />

that reflects where the respondents are situated with respect<br />

to the journey toward “best practice.”<br />

It gives readers an improved tool for judging their own<br />

performance and what constitutes best practice. To be<br />

considered best practice, the level of performance would<br />

have to fall within the top 20% of all respondents.<br />

How Good is the Data<br />

Given that the group of respondents are members of a premier<br />

warehousing and distribution association and/or readers of a<br />

leading distribution magazine, the benchmarks may be better<br />

than the general population of DCs. This organization and<br />

publication tend to attract high performers who are continually<br />

improving their operations.<br />

It is also important that you compare your performance with an<br />

appropriate set of partners. While not as important for comparing<br />

overall service level and customer oriented key performance<br />

indicators, it is especially true when comparing productivity and<br />

cost type metrics. Ideally this would be a firm which is similar in<br />

size and in the same or similar business segment. For this reason,<br />

<strong>WERC</strong> provides a detailed benchmarking report that segments the<br />

benchmarking data by industry, company size, strategy, operations<br />

and type of customer.<br />

“A primary objective for this study is to<br />

provide a benchmark of key measures<br />

by industry and type of business.”<br />

Watch<br />

SPRING 2012<br />

5

What This Year’s Data Said<br />

Table 4 provides a summary of all of the metrics from this year’s study presented in seven columns that are aimed to shed light<br />

about how companies are performing.<br />

• Column 1: Metric<br />

This represents the metrics that is being examined (metric definitions can be found on pages 12-15).<br />

• Columns 2 – 6: Quintile Rankings<br />

These columns split all data responses into five equally divided groups. Each quintile ranking indicates 20% of the responses,<br />

with the five groups representing:<br />

> Major Opportunity: Represents the lowest 20% of responses.<br />

> Disadvantage: Represents responses in the 20-40th percentile.<br />

> Typical: Represents responses in the 40-60th percentile.<br />

• Column 7: Median<br />

This indicates the actual median performance of all respondents.<br />

> Advantage: Represents responses the 60-80th percentile.<br />

> Best Practice: Represents top 20% of all responses.<br />

Table 4. Quintile Performance Classifications for Metrics<br />

Column 1 Column 2 Column 3 Column 4 Column 5 Column 6 Column 7<br />

Customer Metrics* Major Opportunity Disadvantage Typical Advantage Best-in-class Median<br />

On-time Shipments Less than 95.7% >= 95.7 and < 98% >= 98 and < 99.1% >= 99.1 and < 99.8% >= 99.8% 98.5%<br />

Total Order Cycle Time Greater than 72 Hours >= 48 and < 72 >= 22.9 and < 48 >= 5.4 and < 22.9 < 5.4 Hours 33.5 Hours<br />

Internal Order Cycle Time Greater than 36 Hours >= 24 and < 36 >= 8 and < 24 >= 3 and < 8 < 3 Hours 13 Hours<br />

Perfect Order Completion Index Less than 83.6% >= 83.6 and < 94.8% >= 94.8 and < 97.3% >= 97.3 and < 99% >= 99% 95.3%<br />

Lost Sales (Percent of SKUs Stocked Out) Greater than 5.7% >= 2 and < 5.6% >= 1 and < 2% >= 0.29 and < 1% < 0.29% 2%<br />

Backorders as a Percent of Total Orders Greater than 7.4% >= 2.2 and < 7.4% >= 1 and < 2.24% >= 0.2 and < 1% < 0.2% 1.9%<br />

Backorders as a Percent of Total Lines Greater than 5% >= 2 and < 5% >= 1 and < 2% >= 0.2 and < 1% < 0.2% 1.5%<br />

Backorders as a Percent of Total Dollars/Units Greater than 9.2% >= 2.3 and < 9.2% >= 1 and < 2.3 >= 0.2 and < 1 < 0.2% 1.8%<br />

Operations Metrics Major Opportunity Disadvantage Typical Advantage Best-in-class Median<br />

Inbound Metrics<br />

Dock-to-Stock Cycle Time, in Hours Greater than 18.1 Hours >= 8 and < 18.1 >= 4 and < 8 >= 2 and < 4 < 2 Hours 6 Hours<br />

Suppliers Orders Received per Hour Less than 1 per Hour >= 1 and < 2 >= 2 and < 4.7 >= 4.7 and < 10<br />

>= 10<br />

per Hour<br />

3.7 per Hour<br />

Lines Received and Put Away per Hour<br />

Less than 5 Lines<br />

>= 48 Lines per 15 Lines<br />

>= 5 and < 13.2 >= 13.2 and < 20 >= 20 and < 48<br />

per Hour<br />

Hour per Hour<br />

Percent of Supplier Orders Received with<br />

Correct Documents<br />

Less than 90% >= 90 and < 95% >= 95 and < 98% >= 98 and < 99% >= 99% 96%<br />

Percent of Supplier Orders Received<br />

Damage Free<br />

Less than 95% >= 95 and < 98% >= 98 and < 98.5%<br />

>= 98.5 and <<br />

99.04%<br />

>= 99.04% 98%<br />

On-time Receipts from Supplier Less than 85% >= 85 and < 91.8% >= 91.8 and < 95% >= 95 and < 98% >= 98% 94%<br />

Outbound Metrics<br />

Fill Rate – Line Less than 95% >= 95 and < 98% >= 98 and < 99% >= 99 and < 99.8% >= 99.8% 98.5%<br />

Order Fill Rate Less than 90.3% >= 90.3 and < 97% >= 97 and < 99% >= 99 and < 99.8% >= 99.8% 98%<br />

Lines Picked and Shipped per Hour<br />

Less than 14 Lines<br />

>= 81 Lines<br />

>= 14 and < 25 >= 25 and < 43 >= 43 and < 81<br />

per Hour<br />

per Hour<br />

29.9 per Hour<br />

Orders Picked and Shipped per Hour<br />

Less than 2 Orders<br />

>= 29.4 Orders<br />

>= 2 and < 5 >= 5 and < 12 >= 12 and < 29.4<br />

per Hour<br />

per Hour<br />

7.5 per Hour<br />

Cases Picked and Shipped per Hour<br />

Less than 30.9 Cases<br />

>= 255 Cases<br />

>= 30.9 and < 65 >= 65 and < 140 >= 140 and < 255<br />

per Hour<br />

per Hour<br />

99.4 per Hour<br />

Pallets Picked and Shipped per Hour<br />

Less than 7.5 Pallets<br />

>= 27.2 Pallets<br />

>= 7.5 and < 14.3 >= 14.3 and < 20 >= 20 and < 27.2<br />

per Hour<br />

per Hour<br />

19 per Hour<br />

On-time Ready to Ship Less than 95.4% >= 95.4 and < 98% >= 98 and < 99% >= 99 and < 99.8% >= 99.8% 99%<br />

6<br />

®<br />

Watch<br />

SPRING 2012

Table 4. Quintile Performance Classifications for Metrics, CONT.<br />

Column 1 Column 2 Column 3 Column 4 Column 5 Column 6 Column 7<br />

Financial Metrics Major Opportunity Disadvantage Typical Advantage Best-in-class Median<br />

Distribution Costs as a Percent of Sales Greater than 8.9% >= 4.7 and < 8.9% >= 2.9 and < 4.7 >= 1.6 and < 2.98 < 1.6% 3.7%<br />

Distribution Costs as a Percentage of COGS Greater than 15% >= 8.5 and < 15% >= 4.6 and < 8.5 >= 1.8 and < 4.6 < 1.8% 7%<br />

Distribution Costs per Unit Shipped Greater than $10 >= $2.5 and < $10 >= $0.83 and < $2.5 >= $0.3 and < $0.83 < $0.3 $1.32<br />

Days on Hand Raw Materials Greater than 61.2 Days >= 41.4 and < 61.2 >= 28.4 and < 41.4 >= 14 and < 28.4 < 14 Days 30 Days<br />

Days on Hand Finished Goods Inventory Greater than 78 Days >= 45 and < 78 >= 30 and < 45 >= 15 and < 30 < 15 Days 37.4 Days<br />

Inventory Shrinkage as a Percent of<br />

Total Inventory<br />

Greater than 1.8% >= 0.7 and < 1.8% >= 0.2 and < 0.7 >= 0.1 and < 0.2 < 0.1% 0.35%<br />

Capacity/Quality Metrics Major Opportunity Disadvantage Typical Advantage Best-in-class Median<br />

Average Warehouse Capacity Used** Less than 73.2% >= 73.2 and < 80% >= 80 and < 85% >= 85 and < 91.2% >= 91.2% 84.9%<br />

Peak Warehouse Capacity Used** Less than 88.6% >= 88.6 and < 94% >= 94 and < 98% >= 98 and < 100% >= 100% 95%<br />

Honeycomb Percent Less than 15% >= 15 and < 43.8% >= 43.8 and < 70% >= 70 and < 85% >= 85% 50%<br />

Inventory Count Accuracy by Dollars/Units Less than 93.8% >= 93.8 and < 98% >= 98 and < 99.3% >= 99.3 and < 99.8% >= 99.8% 99%<br />

Inventory Count Accuracy by Location Less than 93.4% >= 93.4 and < 97.5% >= 97.5 and < 99.1% >= 99.1 and < 99.8% >= 99.8% 98.8%<br />

Order Picking Accuracy (Percent by Order) Less than 98.3% >= 98.3 and < 99.1% >= 99.1 and < 99.7% >= 99.7 and < 99.9% >= 99.9% 99.5%<br />

Material Handling Damage Greater than 1.7% >= 0.5 and < 1.7% >= 0.12 and < 0.5% >= 0.08 and < 0.12% < 0.08% 0.2%<br />

Equipment/Forklifts Capacity Used Less than 62.6% >= 62.6 and < 75.2% >= 75.2 and < 88.3% >= 88.3 and < 95.8% >= 95.8% 80%<br />

Employee Metrics Major Opportunity Disadvantage Typical Advantage Best-in-class Median<br />

Annual Workforce Turnover Greater than 15.1% >= 8.7 and < 15.1% >= 4.2 and < 8.7% >= 1 and < 4.2% < 1% 5%<br />

Productive Hours to Total Hours Less than 74.7% >= 74.7 and < 82.9% >= 82.9 and < 89.1% >= 89.1 and < 92% >= 92% 85%<br />

Perfect Order Metrics Major Opportunity Disadvantage Typical Advantage Best-in-class Median<br />

Percent of Orders with On-time Delivery Less than 90% >= 90 and < 95.6% >= 95.6 and < 98% >= 98 and < 99.03% >= 99.03% 97.1%<br />

Percent of Orders Shipped Complete Less than 89.7% >= 89.7 and < 96% >= 96 and < 98.5% >= 98.5 and < 99.6% >= 99.6% 98%<br />

Percent of Orders Shipped Damage<br />

Free (Outbound)<br />

Percent of Orders Sent with<br />

Correct Documentation<br />

Less than 97.8% >= 97.8 and < 99% >= 99 and < 99.6% >= 99.6 and < 99.9% >= 99.9% 99.5%<br />

Less than 95.9% >= 95.9 and < 99% >= 99 and < 99.7% >= 99.7 and < 100% >= 100% 99.3%<br />

Cash-to-Cash Metrics Major Opportunity Disadvantage Typical Advantage Best-in-class Median<br />

Inventory Days of Supply Greater than 100.4 Days >= 50.7 and < 100.4 >= 32.8 and < 50.7 >= 21.2 and < 32.8 < 21.2 Days 37.4 Days<br />

Average Days Payable Greater than 60.7 Days >= 45.04 and < 60.7 >= 30 and < 45.04 >= 23.5 and < 30 < 23.5 Days 35 Days<br />

Average Days of Sales Outstanding Greater than 61.3 Days >= 45 and < 61.3 >= 27.1 and < 45 >= 13.9 and < 27.1 < 13.9 Days 35 Days<br />

Which Metrics Really Matter<br />

Each year we identify the Top 12 most popular measures based<br />

on the number of respondents to report results for each metric.<br />

Table 5 shows the Top 12 most popular metrics used and how<br />

that has changed since the 2010 study.<br />

There is strong agreement among DCs and warehouses in<br />

regards to which metrics are critical to measuring performance.<br />

Survey participants still favor the basic metrics they’ve been<br />

using since the beginning of the study.<br />

The only change was in the order of the Top 12 for this year.<br />

This year’s most frequently employed metrics were on-time<br />

shipments, order picking accuracy and average warehouse<br />

capacity used suggesting that veracity, velocity and volume<br />

remain the top concerns for warehouses and DCs.<br />

In terms of performance, the most interesting metric to<br />

watch over the next couple of years will be annual workforce<br />

turnover. While overall performance at the median improved<br />

by 37%, from 8% in 2011 to 5% this year, we believe this is<br />

an indication of the uncertainty that plagues the economy in<br />

terms of employment in 2011 (Figure 8). The labor market is<br />

still lagging other indicators. Our thought is the performance<br />

for annual workforce turnover will “decrease” for median<br />

and best-in-class companies once more people become<br />

comfortable with the current direction of the economy.<br />

Until then, those employees will continue to stay put. As the<br />

economic engine heats up, we expect to see these numbers<br />

return to 2007 levels, when Median performance was 14%.<br />

** Note: Additional customer metrics can be found under Perfect Order Metrics Section.<br />

** Note: Average and Peak Warehouse Capacity does not always reflect best practices. Due to the calculations for quintiles, we have continually reported that best-in-class is above 90%.<br />

A high average warehouse capacity is not beneficial; studies have shown that an average warehouse capacity between 80 and 85% allows the warehouse to respond to shifts in demand.<br />

** Legend: > greater than; >= greater than or equal to; < less than<br />

Watch<br />

SPRING 2012<br />

7

Table 5. Top 12 Most Popular Measures Used<br />

Metric/Metric Category 2011 Rank 2010 Rank<br />

Figure 8. Annual Workforce Turnover<br />

1. On-time Shipments – Customer 1 1<br />

2. Order Picking Accuracy – Quality 3 2<br />

3. Average Warehouse Capacity<br />

Used – Capacity<br />

4. Dock-to-Stock Cycle Time, in<br />

Hours – Inbound Operations<br />

5. Internal Order Cycle Time –<br />

Customer<br />

2 4<br />

5 6<br />

6 10<br />

Performance (Percentage)<br />

15%<br />

12%<br />

9%<br />

6%<br />

3%<br />

Median<br />

Best-in-class<br />

6. Total Order Cycle Time –<br />

Customer<br />

7 –<br />

0%<br />

2005 2006<br />

2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012<br />

7. Peak Warehouse Capacity Used –<br />

Capacity<br />

8. Lines Picked and Shipped per<br />

Hour – Outbound Operations<br />

9. Annual Workforce Turnover –<br />

Employee<br />

10. Fill Rate – Line –<br />

Outbound Operations<br />

11. Lines Received and Put Away per<br />

Hour – Inbound Operations<br />

12. Percent of supplier orders<br />

received damage free –<br />

Inbound Operations<br />

4 9<br />

8 11<br />

12 8<br />

11 3<br />

9 –<br />

10 –<br />

Of interest this year for several metrics is the gap in<br />

performance between median and best-in-class performers.<br />

We are finding that for several metrics the gap is not widening<br />

for the top performers. For example, order picking accuracy,<br />

on-time shipments and fill rate – line have not seen a lot of<br />

movement in terms of performance, i.e., performance has<br />

plateaued at the top end. See Tables 6, 7 and 8 below.<br />

However, performers at the bottom end (major opportunity<br />

performers) are getting better. The normal distribution is<br />

getting narrower, where you still have a large number of the<br />

respondents centered around the median and growing taller<br />

(if you think about a bell shaped curve), but the tail ends<br />

(particularly major opportunity performers) are moving closer<br />

to the median performers.<br />

Table 6. Performance for 2012<br />

Major Opportunity Typical Best-in-class Median<br />

On-time Shipments Less than 95.7% >= 98 and < 99.1% >= 99.8% 98.5%<br />

Order Picking Accuracy Less than 98.3% >= 99.1 and < 99.7% >= 99.9% 99.5%<br />

Fill Rate – Line Less than 95% >= 98 and < 99% >= 99.8% 98%<br />

Table 7. Performance for 2010<br />

Major Opportunity Typical Best-in-class Median<br />

On-time Shipments Less than 95% >= 98 and < 99% >= 99.84% 98.5%<br />

Order Picking Accuracy Less than 98.04% >= 99.12 and < 99.69% >= 99.9% 99.5%<br />

Fill Rate – Line Less than 94.8% >= 97.92 and < 98.88% >= 99.8% 98.5%<br />

Table 8. Performance for 2008<br />

Major Opportunity Typical Best-in-class Median<br />

On-time Shipments Less than 94% >= 97.84 and < 99% >= 99.8% 98.1%<br />

Order Picking Accuracy Less than 98% >= 97.5 and < 98.6% >= 99.9% 99.3%<br />

Fill Rate – Line Less than 94.34% >= 99 and < 99.54% >= 99.7% 98%<br />

8<br />

®<br />

Watch<br />

SPRING 2012

It is interesting to note that the balanced use of measures<br />

continued to show this year. Clearly DCs and warehouses are<br />

taking a forward looking approach by focusing in on customers<br />

and processes rather than financial metrics, which tend to be<br />

lagging indicators of performance.<br />

The Dilemma of Defining<br />

“I heard what you said…But what do you mean”<br />

This dilemma of defining words is nowhere more critical or<br />

often misunderstood than when it comes to on-time delivery.<br />

A supplier knows the customer wants the package on-time,<br />

but what does that really mean To make it more interesting,<br />

each customer can have a different perspective on the term.<br />

The percentage of customers that use each of the different<br />

definitions has changed since we last looked at defining on-time in<br />

2008. We asked respondents what percentage of their customers<br />

used a particular definition of on-time. In other words how many<br />

different definitions of on-time delivery were being used<br />

Table 9. Number of definitions of on-time<br />

Number of Definitions<br />

% of Respondents Using<br />

1 43%<br />

2-3 36.2%<br />

4-5 10.2%<br />

6 or More 10.2%<br />

We found that a majority of respondents still have to deal<br />

with multiple definitions of on-time (Table 9). Over 20% had four<br />

or more definitions of on-time delivery. The difficulty in this is to<br />

communicate clearly with employees as to how the metric is<br />

defined and operationally execute on each expectation.<br />

Unfortunately the majority of respondents, 51.1%, have a very<br />

narrow definition of on-time to meet. Table 10 shows the various<br />

definitions that managers must meet by percentage of their<br />

customers using that definition. The change from 2008, where<br />

over 55% of respondents only had to deliver on the requested<br />

or agreed upon day, is quite stark compared to today. It appears<br />

as though customers have further refined their definitions.<br />

Another factor to consider is the Lean and JIT movements to<br />

reduce excess inventory. Several of the other definitions given<br />

considered on-time to be “right before I need more materials.”<br />

Table 10. Varied definitions of on-time<br />

Metric<br />

% Using<br />

On or Before Appointment Time 15.7%<br />

+ 15 Minutes from the Appointment Time 11.7%<br />

+/- 30 Minutes from the Appointment Time 11.7%<br />

=/- 1 Hour from the Appointment Time 12%<br />

- 1 Hour / + 0 Hours of the Appointment Time 6.6%<br />

On the Requested Day 20.2%<br />

On the Agreed Upon Day 17.1%<br />

Other Definition 5.1%<br />

Softer Side of Performance<br />

Since the inception of this study, our focus has been on the<br />

operational side of performance. The number of labels licked<br />

and boxes kicked per hour, the percent of orders sent damage<br />

free; you name the measure and if it’s important to the industry –<br />

we have the metric. To an extent this is the standard approach,<br />

over several decades, of performance management: Specific,<br />

Measurable, Actionable, Relevant and Timely or “SMART.”<br />

Then in the early 1990’s two Harvard Business professors turned<br />

the world of performance upside down with the balanced<br />

scorecard. In order to understand how we are performing<br />

as a company, we need to look at our performance from all<br />

sides: financial, customer, growth and learning, and internal<br />

processes. Unfortunately, many companies continue to look<br />

at “hard” operational measures to determine performance for<br />

these categories. Over the last several years, some academics<br />

and consulting firms have been conducting field-based research<br />

and found a few companies are starting to augment traditional<br />

“hard” operational measures with an evaluation of the “softer”<br />

side of business performance.<br />

Watch<br />

SPRING 2012<br />

9

Soft considerations include assessing the Relationship Quality,<br />

such as communication and collaboration approaches and trust<br />

in the relationship; and Organization Culture, such as leadership<br />

orientation, innovation and team focus.<br />

Communication<br />

Approaches<br />

Relationship Quality<br />

(Performance)<br />

Collaboration<br />

Approaches<br />

Trust<br />

Leadership<br />

Orientation<br />

Organization Culture<br />

(Suitability)<br />

Innovation<br />

Team Focus<br />

Why measure the softer side of business<br />

Most supply chain managers are accustomed to measuring<br />

operational performance, and they typically have an affinity for<br />

and are skilled in this type of analysis. Today it is easier than<br />

ever to measure the operational aspects of a business, thanks to<br />

the availability of free or inexpensive operational benchmarking<br />

data through organizations like the Warehousing Education and<br />

Research Council (<strong>WERC</strong>). The advent of automated scorecards,<br />

dashboards, financial analyses and reporting tools has also<br />

made it easier to accurately measure operational performance.<br />

Operational analysis is a top priority in today’s business<br />

environment, which has driven companies to manage by the<br />

numbers and emphasize bottom-line results. And when the<br />

going gets tough, organizations focusing solely on bottomline<br />

results tend to revert to what they know best. In the<br />

case of performance measurement, the tendency is to place<br />

“Today it is easier than ever to measure<br />

the operational aspects of a business.”<br />

10<br />

®<br />

Watch<br />

SPRING 2012

additional emphasis on improved operational efficiency at<br />

both the organizational and individual levels. As a result, many<br />

organizations are reducing the number of customer-facing<br />

personnel they employ, slighting customer service and imposing<br />

greater pressure and unfavorable terms on vendors.<br />

Without solid relationships to back them up, however, the<br />

operational components of a business are unlikely to be<br />

successful. Simply put, the interpersonal skills that promote<br />

and nurture strong relationships—the ability to communicate<br />

well, interact effectively with others, make mutually beneficial<br />

decisions, solve problems jointly and collaborate—can have<br />

as direct an impact on supply chain performance as do the<br />

operational aspects of a business.<br />

To develop a true picture of supply chain success, then,<br />

organizations must measure both the “what” (operational)<br />

and the “how” (interpersonal) aspects of performance. The<br />

importance of these soft skills dictates a need for a new<br />

generation of business metrics and scorecards able to gauge<br />

both sides of performance.<br />

Which “Soft” Skills Should You Measure<br />

We want to advocate for the soft side of supplier and customer<br />

relationships because we believe companies that don’t formally<br />

measure the overall health of their trading partner relationships<br />

are myopic.<br />

This is particularly important in the supply chain arena. The<br />

effectiveness of a supply chain relationship with customers<br />

Soft Metrics<br />

Communication Approaches<br />

Collaboration Approaches<br />

Trust<br />

Leadership Approaches<br />

Innovation<br />

Team Focus<br />

Table 11. Soft Metrics<br />

Concepts<br />

Communication frequency and effectiveness<br />

People management including clarity of<br />

direction and respect<br />

Conflict management and collaboration styles<br />

Decision making and problem solving<br />

Delegation and governance<br />

Cooperation, openness and behavior<br />

Trustworthiness, ethics and integrity<br />

Culture, values and equality of stakeholders<br />

Leadership styles and accountability of actions<br />

Creativity and alignment of strategic direction<br />

Flexibility, agility and speed of response<br />

Improvement and change management<br />

Balanced risk and rewards<br />

Goal setting and shared vision<br />

Peer-to-peer cross-functional teams<br />

Value (reward) and recognition<br />

Win-win orientation<br />

“Interpersonal relationships directly impact such factors<br />

as purchase/repurchase decisions, sharing critical<br />

information, collaborative education (educating each<br />

other on critical aspects of the product, strategy, or<br />

service) and the degree of strategic partnership.”<br />

and suppliers depends heavily upon non-operational elements<br />

of performance: employees’ ability to communicate well,<br />

personally interface with counterparts at other companies,<br />

make mutually beneficial decisions, solve problems jointly,<br />

and collaborate. Interpersonal relationships directly impact<br />

such factors as purchase/repurchase decisions, sharing critical<br />

information, collaborative education (educating each other<br />

on critical aspects of the product, strategy, or service) and<br />

the degree of strategic partnership. Sacrificing any of these<br />

elements for short-term gain can often have negative, long-term<br />

consequences on supply chain relationships, which is likely<br />

to have severe consequences for a company as a whole.<br />

If you are not yet convinced that the softer side of business<br />

performance should be measured alongside operational<br />

metrics, then consider the following highlights from research<br />

conducted by the University of Tennessee. Their results show<br />

how some companies are benefiting from measuring both sides<br />

of performance.<br />

Soft on Metrics<br />

Field-based research conducted by the University of Tennessee<br />

(UT) on performance-focused outsourcing agreements shows<br />

that the “soft stuff” involved in building long-term supplier<br />

relationships genuinely matters. UT researchers have studied<br />

highly successful outsourcing relationships across all industries<br />

and functions being outsourced. They have seen a clear trend<br />

toward companies reducing the number of operational metrics<br />

and increasing the number of soft metrics.<br />

In one outsourcing relationship the UT teams studied, the<br />

company and the service provider went so far as to remove all<br />

of the task-level service agreements from their contract. Instead,<br />

they relied on just three, high-level “critical success factors” to<br />

gauge operational performance. The contract also spelled out<br />

nine additional “soft” metrics, including such hard to measure<br />

items as “flexibility” and “responsiveness.”<br />

Watch<br />

SPRING 2012<br />

11

The most unusual metric in the relationship addressed what the<br />

companies termed “discretionary governance.” This was an<br />

index derived from surveying the top 40 people involved in the<br />

outsourcing relationship, ranging from those with direct control<br />

to major stakeholders in the affected business units. The goal<br />

of the discretionary governance index was to gauge the overall<br />

“happiness” of the relationship. The companies referred to the<br />

index as “discretionary governance” because the parties had<br />

agreed to tie a full 20 percent of the service provider’s fees to the<br />

index—a rarity in a world where most companies only want to<br />

make payments based on bullet-proof, quantifiable metrics. UT<br />

researchers came to call the discretionary governance metric<br />

the “happy factor” because the happier the company, the bigger<br />

the payout for the service provider.<br />

It may sound far-fetched, but the company named this<br />

particular supplier “Supplier of the Year” two years in a row—<br />

out of 80,000 suppliers. The supplier confirms that focusing on<br />

the softer side of supply chain performance has helped it to build<br />

deep and meaningful relationships, which are driving overall<br />

business success. n<br />

Metric Definitions<br />

One ongoing goal of this study is to help practitioners link key<br />

measures to various demographics to help companies better<br />

compare themselves to organization similar to their own.<br />

As pointed out in the study, there is often a lack of consensus—<br />

or sometimes, understanding—of what the metrics actually mean.<br />

Over the past five years we have been told that companies<br />

have adopted these definitions and calculations across their<br />

organizations in an attempt to develop a consistent approach<br />

to reporting performance at each location. This has been one<br />

aspect of the study that is most rewarding. Use of an agreed upon<br />

standard and definition will go a long way in assisting firms to<br />

understand and compare internal performance.<br />

Definitions for the key operational metrics are provided here—<br />

grouped into categories to help you interpret the metrics in<br />

the report—as well as to provide a common understanding<br />

for benchmarking. n<br />

Customer Metrics Definition Calculation<br />

On-time Shipments<br />

Total Order Cycle Time<br />

Internal Order Cycle Time<br />

Perfect Order Index<br />

Lost Sales<br />

(Percentage SKUs Stocked Out)<br />

Backorders as a Percentage of<br />

Total Orders<br />

and/or<br />

Backorders as a Percentage of<br />

Total Lines<br />

and/or<br />

Backorders as a Percentage of<br />

Total Dollars / Units<br />

The percentage of orders shipped at the planned time (shipped means off<br />

the dock and in transit to its final destination).<br />

NOTE: The time to ship may be defined by the customer, or it may be<br />

determined by the shipper in order to accommodate an on-time delivery.<br />

The average end-to-end time between order placement by the customer<br />

and order receipt by the customer.<br />

The average internal time between when the order was received from the<br />

customer and order shipment by the supplier.<br />

NOTE: Order shipment is defined as off of the dock, onto the shipping<br />

conveyance and ready for transit.<br />

A compilation score which measures the result of each of the 4 major<br />

components of a perfect order:<br />

• Delivered On-time<br />

• Shipped Complete<br />

• Shipped Damage Free • Correct Documentation<br />

An important risk indicator: the percentage of sales lost due to stock outs.<br />

The portion of total orders that are held and shipped late due to lack of<br />

availability of stock. Can be measured by lines or by PO, by units or by<br />

dollar value.<br />

Number of order shipped on-time /<br />

Total number of orders shipped<br />

Excluding non-working days: sum of<br />

(Time order received by customer – Time<br />

order placed) / Total number of orders shipped<br />

Excluding non-working days: sum of<br />

(Time order shipment – Time order received<br />

from the customer) / Number of orders shipped<br />

The Perfect Order Index (POI) is established<br />

by multiplying each component of the perfect<br />

order to one another. For example, if a company<br />

is experiencing a measure of 95% across all 4<br />

metrics of the perfect order (on-time, complete,<br />

damage free and correct documentation), the<br />

resulting perfect order index would be 81.4%<br />

Dollar sales that were lost (i.e., they did not<br />

become backorders) / Total sales<br />

Number of orders held and not shipped /<br />

Total number of orders<br />

Number of order lines held and not shipped /<br />

Total number of order lines<br />

Number of order dollars or units held and not<br />

shipped / Total number of order dollars or units<br />

Operations Metrics Definition Calculation<br />

Inbound Metrics<br />

Dock-to-Stock Cycle<br />

Time, in Hours<br />

The dock-to-stock cycle time equals the time (typically measured in hours)<br />

required to put away goods. The cycle time begins when goods arrive from<br />

the supplier and ends when those goods are put away in the warehouse and<br />

recorded into the inventory management system.<br />

For a given time period: sum of the cycle time<br />

in hours for all supplier receipts / Total number<br />

of supplier receipts<br />

12<br />

®<br />

Watch<br />

SPRING 2012

Supplier Orders Received<br />

per Hour<br />

Lines Received and<br />

put Away per Hour<br />

Measures the productivity of receiving operations in supplier orders<br />

processed per person hour.<br />

Measures the productivity of receiving operations in lines processed<br />

and put away per person hour.<br />

Total supplier orders processed in receiving / Total<br />

person hours worked in the receiving operation<br />

Total lines received and put away / Total person<br />

hours worked in the receiving operation<br />

Percent of Supplier Orders<br />

Received With Correct<br />

Documentation<br />

Percent of Supplier Orders<br />

Received Damage Free<br />

On-time Receipts<br />

From Supplier<br />

Fill Rate – Line<br />

Order Fill Rate<br />

Lines Picked and Shipped<br />

per Person Hour<br />

and/or<br />

Orders Picked and Shipped<br />

per Person Hour<br />

and/or<br />

Cases Picked and Shipped<br />

per Person Hour<br />

and/or<br />

Pallets Picked and Shipped<br />

per Person Hour<br />

The number of orders that are processed with complete and correct<br />

documentation as a percentage of total orders.<br />

Documentation includes packing slips, case and pallet labeling,<br />

certifications, ASN, carrier documents or other documents as required<br />

by the purchase order.<br />

The number of orders that are processed damage free as a percentage<br />

of total orders.<br />

Percent of orders received from a supplier on the date requested.<br />

Outbound Metrics<br />

Measures percent of orders lines filled according to customer request.<br />

NOTE: A single customer order line can request multiple shipments.<br />

In this case each shipment would be tracked as a separate request.<br />

Measures percent of orders filled according to customer request.<br />

NOTE: A single customer order can request multiple shipments.<br />

In this case each shipment would be tracked as a separate request.<br />

Measures the productivity of picking and shipping operations<br />

in lines per person hour.<br />

Measures the productivity of picking and shipping operations<br />

in orders per person hour.<br />

Measures the productivity of picking and shipping operations<br />

in cases per person hour.<br />

Measures the productivity of picking and shipping operations<br />

in pallets per person hour.<br />

Number of supplier orders that are processed with<br />

complete and correct documents / Total supplier<br />

orders processed in the measurement period<br />

Number of supplier orders that are processed<br />

damage free / Total supplier orders processed in<br />

the measurement period<br />

Number of supplier orders received on-time /<br />

Total number of orders received<br />

Percentage of orders lines filled to customer<br />

request / Total number of order lines filled<br />

Number of orders filled to customer request /<br />

Total number of orders filled<br />

For a given time period:<br />

Total order lines picked and shipped / Total hours<br />

worked in the picking and shipping operation<br />

Total orders picked / Total hours worked in the<br />

picking and shipping operation<br />

Number of cases picked and shipped / Total hours<br />

worked in the picking and shipping operation<br />

Number of pallets picked and shipped / Total hours<br />

worked in the picking and shipping operation<br />

On-time Ready to Ship<br />

The percentage of orders ready for shipment at the planned time.<br />

NOTE: “Ready for shipment” typically means that packaging and<br />

shipping documents are completed and ready for pickup.<br />

Number of orders ready for shipment on-time /<br />

Number of total orders shipped<br />

Financial Metrics Definition Calculation<br />

Distribution Cost as a<br />

Percent of Sales<br />

The cost to run distribution relative to total sales. Activities included in the<br />

operate warehousing process are: management activities, track inventory<br />

deployment, receive, inspect and store inbound deliveries, track product<br />

availability, pick, pack and ship product for delivery, track inventory<br />

accuracy, track third-party logistics storage and shipping performance.<br />

Total distribution costs / Total sales<br />

Distribution Costs as a<br />

Percent of COGS<br />

The cost to run distribution relative to COGS. Activities included as part<br />

of total distribution operating costs are: management activities, track<br />

inventory deployment, receive, inspect and store inbound deliveries, track<br />

product availability, pick, pack and ship product for delivery, track inventory<br />

accuracy, track third-party logistics storage and shipping performance.<br />

Total distribution costs / Total COGS<br />

(based on corporate income statement)<br />

Distribution Cost<br />

per Unit Shipped<br />

The cost to run distribution relative to the units shipped through distribution.<br />

Distribution costs include: management activities, track inventory<br />

deployment, receive, inspect and store inbound deliveries, track product<br />

availability, pick, pack and ship product for delivery, track inventory<br />

accuracy, track third-party logistics storage and shipping performance.<br />

Total cost of operating distribution /<br />

Total units shipped<br />

Watch<br />

SPRING 2012<br />

13

Inventory Shrinkage as a<br />

Percent of Total Inventory<br />

The amount of breakage, pilferage and deterioration of all inventories relative<br />

to total inventory. Usually stated in terms of value, not units.<br />

Sum (value of breakage, pilferage, deterioration<br />

to all inventory) / Total value of all inventory<br />

Days on Hand –<br />

Raw Materials<br />

The number of productive days before raw material supply is consumed.<br />

Gross raw material inventory value / Average daily<br />

value of raw material usage<br />

Days on Hand –<br />

Finished Goods Inventory<br />

Average sales days of finished goods inventory on hand in plants<br />

and warehouses.<br />

Average finished goods inventory value ($) /<br />

Average daily sales $ per month<br />

Capacity & Quality Metrics Definition Calculation<br />

Average Warehouse<br />

Capacity Used<br />

The average amount of warehouse capacity used over a specific amount<br />

of time (month to month or yearly).<br />

Average capacity used / Average<br />

capacity available<br />

Peak Warehouse<br />

Capacity Used<br />

The amount of warehouse capacity used during designated peak seasons.<br />

Peak capacity used / Capacity available<br />

Honeycomb Percentage<br />

Measures how well actual cube utilization within the warehouse is<br />

managed. Especially important where slots may be only partially full.<br />

An example would be if 1 unit is in a location, and it has room for 10,<br />

the utilization for that slot/bin location is 10%.<br />

Actual cube utilization / Total warehouse<br />

cube positions available<br />

Inventory Count Accuracy<br />

(by Units/Dollars)<br />

and/or<br />

Inventory Count Accuracy<br />

(Percent by Location)<br />

Measures the accuracy (by location and units) of the physical inventory<br />

compared to the reported inventory: If the warehouse management system<br />

indicates that 10 units of part number XYZ are in slot B0029, the inventory<br />

count accuracy indicates how frequently one can go to that location and<br />

find that the physical count matches the system’s.<br />

1 - (The sum of the absolute variance in units<br />

or dollars / The sum of the total inventory in units<br />

or dollars)<br />

1 - (The sum of the number of locations containing<br />

an error / The total number of locations counted)<br />

Order Picking Accuracy<br />

This measures the accuracy of the orders picking process where errors<br />

may be caught prior to shipment such as during packaging.<br />

Orders picked correctly / Total orders picked<br />

Material Handling Damage<br />

Measures the value of material damaged from handling/storage<br />

as a percentage of COGS.<br />

The value of material damaged from<br />

handling/storage / COGS<br />

Equipment/Forklift<br />

Capacity Used<br />

The amount of up time logged for equipment/forklifts.<br />

Total amount of time equipment is used /<br />

Total amount of planned available time for use<br />

Employee Metrics<br />

Definition<br />

Annual Workforce Turnover<br />

The rate at which permanent employees are replaced (excludes casual<br />

or seasonal labor).<br />

Number of NEW employees at the beginning<br />

of the period / Total number of employees at the<br />

beginning of the previous period<br />

Productive Hours<br />

to Total Hours<br />

Measures employee productivity against total hours (includes all<br />

hours—indirect and direct).<br />

Hours charged to specific activities, tasks<br />

or projects / Total hours worked<br />

14<br />

®<br />

Watch<br />

SPRING 2012

Perfect Order Metric Definition Calculation<br />

Percent of Orders with<br />

On-time Delivery<br />

The percentage of orders that arrive at their final destination at the<br />

agreed upon-time.<br />

NOTE: There are many definitions of “on-time,” and that the “time” may<br />

be a specific hour or day, or a window of time. “Agreed upon” means that<br />

the customer and shipper have agreed to the delivery time as a general<br />

commitment or as a part of the purchase order or contract.<br />

Number of orders delivered on-time /<br />

Total number of orders shipped<br />

Shipped Complete<br />

per Customer Order<br />

Measures the percentage of orders which shipped completely, meaning<br />

that all line/units ship with the order per agreement between the customer<br />

and shipper.<br />

Number of orders shipped with all lines and units /<br />

Total number of orders shipped<br />

Shipped Damage Free<br />

(Outbound)<br />

This measures the percentage of customer orders shipped in good and<br />

usable condition.<br />

NOTE: Orders damaged in transit are not considered here.<br />

Number of orders shipped damage free /<br />

Number of total orders shipped<br />

Correct Documentation<br />

(ASN, Invoice, etc.)<br />

The percent of total orders for which the customers received an accurate<br />

invoice and other required documents including ASNs, etc.<br />

Number of orders with correct documentation /<br />

Number of total orders<br />

Cash-To-Cash Metrics Definition Calculation<br />

Inventory Days of Supply<br />

Average Days Payable<br />

Average Days Sales<br />

Outstanding<br />

Measure of quantity of inventory-on-hand, in relation to number of days for<br />

usage which will be covered. Total gross value of inventory at standard cost<br />

before reserves for excess and obsolescence. Only includes inventory on<br />

company books, future liabilities should not be included.<br />

Measure of the length of time required to pay suppliers; key element in<br />

cash-to-cash cycle time.<br />

The amount of time required to convert receivables to cash. To even out<br />

seasonality, this includes a rolling monthly average of AR (this is also<br />

known as “average collection period”).<br />

Current (or period ending) total inventory value /<br />

(Total annual COGS / 365)<br />

Average daily payables / (Total annual COGS / 365)<br />

Average 5 month AR / (Total annual sales / 365)<br />

Watch<br />

SPRING 2012<br />

15

WAREHOUSING EDUCATION AND RESEARCH COUNCIL<br />

THE ASSOCIATION FOR LOGISTICS PROFESSIONALS<br />

1100 Jorie Boulevard, suite 170<br />

Oak brook, Illinois 60523-4413<br />

Research Team<br />

Joseph M. Tillman is a Senior Researcher at Supply Chain<br />

Visions. Joe began his work on the study while an MBA<br />

student at Georgia Southern University. He is a blogger for<br />

DCVelocity.com on Young Professionals in Logistics. He has<br />

held positions with Walmart and Union Pacific prior to joining<br />

Supply Chain Visions.<br />

Karl B. Manrodt, PhD, Professor, Georgia Southern University,<br />

is also the Co-Director of the Southern Center for Logistics<br />

and Intermodal Transportation. Recognized as a 2004<br />

Rainmaker by DC Velocity, his research has appeared in<br />

leading academic and practitioner journals. Dr. Manrodt is<br />

a recognized speaker, and is one of the authors of Keeping<br />

Score: Measuring the Business Value of Logistics in the<br />

Supply Chain. In addition Dr. Manrodt blogs for DCVelocity.com<br />

on metrics and benchmarking.<br />

Kate L. Vitasek, MBA, is the founder and Managing Partner<br />

of Supply Chain Visions, a small consulting practice that<br />

specializes in supply chain strategy and education. Kate<br />

has been widely published, and she currently blogs for<br />

DCVelocity.com on Bad Warehouses. She was recognized<br />

as a Rainmaker by DC Velocity in 2004. She is a well-known<br />

speaker for industry groups and universities and currently<br />

teaches seminars for <strong>WERC</strong>. n<br />

<strong>WERC</strong>watch findings reflect what <strong>WERC</strong> members are experiencing and predicting<br />

within their U.S. distribution networks. There is no presumption that the findings<br />

are representative of an entire industry sector, product category or type of firm.<br />

<strong>WERC</strong>watch is published by <strong>WERC</strong>, 1100 Jorie Blvd., Suite 170, Oak Brook, IL 60523-4413.<br />

©2012, Warehousing Education and Research Council. All rights reserved.<br />

Our Observations<br />

Overall, it is encouraging to see an increase and continual<br />

support of measurement as a key practice in most organizations<br />

by senior executives. Today’s demands require organizations to<br />

adopt a balanced approach between the hard and soft sides of<br />

performance measurement. How we get results is as important<br />

to supply chain effectiveness as what we achieve.<br />

As performance measurement moves beyond operational<br />

metrics to include interpersonal performance, companies<br />

should emphasize both equally. As we have demonstrated,<br />

effective interpersonal behaviors lead to stronger relationships,<br />

which lead to better operational performance. Organizations<br />

that fail to consider the interpersonal component eventually<br />

find that this failure has serious consequences for their<br />

operational performance. Because of this, the new generation<br />

of business metrics and scorecards must reflect this thinking<br />

if they are to capture the full picture of supply chain success.<br />

What does the future hold Overall, we believe that the bestin-class<br />

facilities will continue to lead the way to continued<br />

performance, especially on the softer side. This march to<br />

excellence will not be inexpensive nor without effort. All of the<br />

low hanging opportunities have been identified and corrected.<br />

The last push towards excellence will not only benefit his or<br />

her firm, but will increase everyone’s understanding of what<br />

is possible. n<br />

Acknowledgments<br />

<strong>WERC</strong> thanks the sponsoring<br />

company who helped make<br />

this report possible:<br />

warehousing education and research council • 1100 Jorie blvd, ste 170, Oak Brook, IL 60523-4413<br />

P | 630.990.0001 F | 630.990.0256 E | wercoffice@werc.org W | www.werc.org