Untitled - Terre des Hommes

Untitled - Terre des Hommes

Untitled - Terre des Hommes

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Stichting <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong> Nederland<br />

Zoutmanstraat 42-44<br />

2518 GS The Hague<br />

Tel. (070) 3105000<br />

E-mail: info@tdh.nl<br />

Internet: www.terre<strong>des</strong>hommes.nl<br />

Authors: Marianna Närhi, Lucien Stöpler<br />

Fieldwork: Koosje van der Loo, Marianna Närhi, Imke van der Velde<br />

Desk study: Jasper Wouda, Ikram Cakir<br />

Cover: Sven Torfinn<br />

Copyright: <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong> Nederland, March 2010<br />

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction.<br />

2

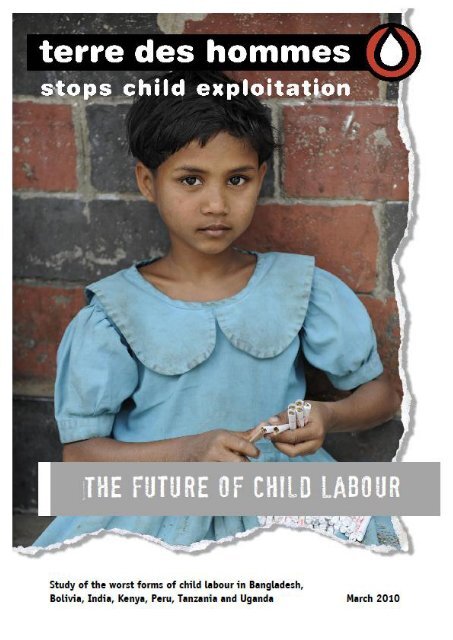

The Future of Child Labour<br />

Study of the worst forms of child labour in Bangla<strong>des</strong>h, Bolivia, India, Kenya, Peru,<br />

Tanzania and Uganda<br />

Table of Contents<br />

Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................. 5<br />

Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 6<br />

The research ......................................................................................................................................... 7<br />

Legal analysis of child labour ............................................................................................................. 8<br />

Bibliography ...................................................................................................................... 15<br />

Bangla<strong>des</strong>h .......................................................................................................................................... 17<br />

1. Introduction and background to child exploitation ................................................ 17<br />

2. Law and policy .............................................................................................................. 18<br />

3. Forms .............................................................................................................................. 19<br />

4. Interventions .................................................................................................................. 27<br />

5. Recommendations by respondents ............................................................................ 31<br />

6. Bibliography .................................................................................................................. 32<br />

7. List of respondents ........................................................................................................ 33<br />

India ..................................................................................................................................................... 35<br />

1. Introduction and background to child exploitation ................................................ 35<br />

2. Law and policy .............................................................................................................. 36<br />

3. Forms .............................................................................................................................. 38<br />

4. Interventions .................................................................................................................. 44<br />

5. Recommendations by respondents ............................................................................ 47<br />

6. Bibliography .................................................................................................................. 48<br />

7. List of respondents ........................................................................................................ 49<br />

Bolivia .................................................................................................................................................. 51<br />

1. Introduction and background to child exploitation ................................................ 51<br />

2. Law and policy .............................................................................................................. 53<br />

3. Forms .............................................................................................................................. 54<br />

4. Interventions .................................................................................................................. 60<br />

5. Recommendations by respondents ............................................................................ 63<br />

6. Bibliography .................................................................................................................. 64<br />

7. List of respondents ........................................................................................................ 65<br />

Peru ...................................................................................................................................................... 67<br />

1. Introduction and background to child exploitation ................................................ 67<br />

2. Law and policy .............................................................................................................. 69<br />

3. Forms .............................................................................................................................. 70<br />

4. Interventions .................................................................................................................. 75<br />

5. Bibliography .................................................................................................................. 78<br />

3

6. List of respondents ........................................................................................................ 79<br />

Kenya ................................................................................................................................................... 81<br />

1. Introduction and background to child exploitation ................................................ 81<br />

2. Law and policy .............................................................................................................. 82<br />

3. Forms .............................................................................................................................. 83<br />

4. Interventions .................................................................................................................. 86<br />

5. Recommendations by respondents ............................................................................ 88<br />

6. Bibliography .................................................................................................................. 89<br />

7. List of respondents ........................................................................................................ 90<br />

Tanzania .............................................................................................................................................. 92<br />

1. Introduction and background to child exploitation ................................................ 92<br />

2. Law and policy .............................................................................................................. 93<br />

3. Forms .............................................................................................................................. 95<br />

4. Interventions .................................................................................................................. 97<br />

5. Recommendations by respondents ............................................................................ 99<br />

6. Bibliography .................................................................................................................. 99<br />

7. List of respondents ...................................................................................................... 100<br />

Uganda .............................................................................................................................................. 101<br />

1. Introduction and background to child exploitation .............................................. 101<br />

2. Law and policy ............................................................................................................ 102<br />

3. Forms ............................................................................................................................ 103<br />

4. Interventions ................................................................................................................ 106<br />

5. Recommendations by respondents .......................................................................... 108<br />

6. Bibliography ................................................................................................................ 109<br />

7. List of respondents ...................................................................................................... 110<br />

General conclusions ......................................................................................................................... 111<br />

Recommendations ............................................................................................................................ 116<br />

Annex ................................................................................................................................................. 118<br />

4

Acknowledgements<br />

The researchers, authors and <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong> Netherlands would like to express our sincere<br />

gratitude to all the people who provided a warm welcome and invaluable support to the researchers,<br />

and those who took the time to explain their position, share information and advance discussions. In<br />

particular we would like to thank:<br />

Mr. Kabir, Mr. Ehsan, and all the staff at the <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong> office in Bangla<strong>des</strong>h, as well as Mr.<br />

Latif (Society for Social Service) and all project partners in Bangla<strong>des</strong>h;<br />

Kathia, Monica and all the staff at the <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong> office in Bolivia;<br />

Mr. Miller, Mr. Ranjit and all the staff at the <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong> office in India, as well as Mr. Nagaraj<br />

(Vidiyanikethan) and all project partners in India;<br />

Petra, Eliab, Liz and all the staff at the <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong> office in Kenya;<br />

Carmen, and all the staff at the <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong> office in Peru, as well as Asociación Mujer Familia<br />

and El Instituto de Investigación y Capacitación Profesional in Peru;<br />

Mr. Lei Brouns at the <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong> regional office in Sri Lanka;<br />

Ank, Jamal and all the staff at the <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong> office in Tanzania, as well as Kivulini and<br />

Centre for Widows and Children Assistance in Tanzania;<br />

Platform for Labour Action and Jinja Network in Uganda.<br />

Lastly, we would like to thank the children who participated in this research and inspired us with<br />

their strength, endurance and brightness.<br />

5

Introduction<br />

This report is based on fieldwork carried out in three of the regions where <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong><br />

Netherlands is active. The purpose of the research was to collect information on the worst forms of<br />

child labour by talking to stakeholders on different levels; from children, parents and employers to<br />

NGO’s, police and the government. What kind of work do children do, why are they doing it, and<br />

why is it harmful to them What is being done to eliminate child labour, what has been achieved and<br />

why does child labour prevail What are recent shifts in child labour in these countries, and how are<br />

global trends affecting this Running up to The Hague Global Child Labour Conference being hosted<br />

by the Dutch Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment, in close collaboration with the ILO in May<br />

2010, <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong> is presenting some of the current statistics, trends, opinions and<br />

recommendations presiding amongst those involved with child labour in Bangla<strong>des</strong>h, Bolivia, India,<br />

Kenya, Peru, Tanzania and Uganda.<br />

Compiling this into one report makes it possible to draw parallels between regions and countries.<br />

The prevalence of child domestic labour, and the abusive and slave-like conditions under which<br />

much of it takes place, was apparent in all research areas. The connections between domestic labour<br />

and unconditional worst forms of child labour such as trafficking and prostitution are unavoidable,<br />

and add to the urgency of developing appropriate response s to the exploitation faced by millions of<br />

children in this most common of employment sectors. The commercial sexual exploitation of children<br />

remains wi<strong>des</strong>pread, and the role of boys is often not well understood. Urbanisation and large-scale<br />

rural to urban migration are leading to growing slums and increasing populations of invisible,<br />

unsupervised, vulnerable children. HIV/AIDS, climate change, and the global economic crisis are<br />

pushing more and more children into exploitative situations. Children often do not receive sufficient<br />

protection from their families, their communities and state protection mechanisms. Although school<br />

enrolment rates are increasing across the researched regions, many children remain without viable<br />

alternatives to working. Different cultural perspectives on child labour, and discrepancies in the<br />

approaches taken by various local, national and international actors, affect the responses to child<br />

labour and the impact these have. This report aims to contribute to the on-going discussion about<br />

how best to protect children from exploitation by collating information and viewpoints from various<br />

sources.<br />

6

The research<br />

The research was carried out by Imke van der Velde in East Africa, Koosje van der Loo in South<br />

America and Marianna Närhi in South Asia. The fieldwork took place between September and<br />

December 2009. Initial points of contact in the field were the <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong> regional and country<br />

offices. Here the preliminary research frameworks were discussed, and appointments were made to<br />

visit project partners and organisations and people identified as relevant to the research. The<br />

majority of interviews were semi-structured, based on the topics in the questionnaire (see annex),<br />

adjusted according to the respondent. Translators were used for some interviews. With regards to<br />

interviews with children, an adult familiar to the child (generally a counsellor or a teacher) was<br />

always present. This report has been compiled from the interview notes and written reports collected<br />

during this time.<br />

The references to the interviews can be found in the footnotes; written sources are referred to in-text<br />

and in the bibliographies.<br />

7

Legal analysis of child labour<br />

The starting point for this research was a series of international legal agreements that define child<br />

labour. These are the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and its two protocols, the<br />

International Conventions on both Civil and Political as well as Economic Social and Cultural Rights,<br />

several conventions by the International Labour Organisation, the UN Convention on Transnational<br />

Organized Crime and its protocol and a series of Security Council Resolutions against the use of child<br />

soldiers.<br />

The Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) states in article 32 the general principle that children<br />

have the right to be: ‘protected from economic exploitation and from performing any work that is<br />

likely to be hazardous or to interfere with the child's education, or to be harmful to the child's health<br />

or physical, mental, spiritual, moral or social development.’ Measures regulating working conditions<br />

and a minimum age are to be established by a state, as well as penalties to enforce these measures. In<br />

the subsequent articles 33-34, children’s rights to be protected against illicit activities, sexual<br />

exploitation and trafficking, respectively, are laid down. The first optional protocol to the CRC (2000)<br />

provi<strong>des</strong> an age limit of 18 to involvement of children in armed conflict. The second optional protocol<br />

to the CRC aims at the elimination of the sale and sexual exploitation of children. The Committee on<br />

the Rights of the Child, which monitors the implementation of the CRC, has further made references<br />

to other conventions and agreements that have similar aims as those of the CRC and its protocols,<br />

calling attention to the norms therein professed by the signatory state (General Comment no. 4, para<br />

18). Similar references are made in the concluding observations on Finland (1996), Gambia (2001),<br />

Lebanon (2002), Oman (2001) (quoted by Fodella in Nesi, Nogler and Pertile, 2008).<br />

The international Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) contains a general provision on the<br />

protection of the child: ‘Every child shall have, without any discrimination < the right to such<br />

measures of protection as are required by his status as a minor, on the part of his family, society and<br />

the State,’ (article 24). This does not contain any specific mention of child labour, but the Human<br />

Rights Commission has extended its mandate into this area by the commentaries it has made. 1 Special<br />

about the ICCPR is both its monitoring system, which allows inter-state complaints, as well as<br />

individual redress, which makes these justiciable and individual rights.<br />

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights names the protection against<br />

economic and social exploitation in article 10. Furthermore, although the provisions of the ICESCR<br />

are generally considered to be achieved progressively and to the maximum of a states available<br />

resources, this article is identified as one by which the legal system can be achieved immediately.<br />

Convention 182 of the International Labour Organisation (ILO) was accepted by the International<br />

Labour Conference (ILC) in 1999 and it defines ‘the worst forms of child labour’. These worst forms<br />

are: all forms of slavery or practices similar to slavery; prostitution, pornography and pornographic<br />

performances; the use of children in illicit activities; and hazardous work. These forms of child labour<br />

have been identified as the forms that required immediate prohibition and elimination. For this<br />

research, Convention 182 is used as the guiding convention, because it contains all the forms of child<br />

labour that this research focuses on. This convention is not always the leading or most important<br />

1<br />

See among many examples (these are taken from Fodella in Nesi, Nogler and Pertile): HRC, Concluding<br />

Observations on Uganda, A/59/40 vol. I (2004) 47: The State party should adopt measures to avoid the<br />

exploitation of child labour and to ensure that children enjoy special protection, in accordance with article<br />

24…’; Kyrgizstan (ICCPR, A/55/40 vol. I (200); Portugal (ICCPR, A/58/40 vol. I (2003); Uzbekistan (ICCPR,<br />

A/60/40 vol. I (2005); Brazil, ICCPR, A/51/40 vol. I (1996): The State party should eforce laws prohibiting …<br />

child labour and child prostitution and should implement programmes to prevent and combat such human rights<br />

abuses’.<br />

8

convention on a particular subject, but it does contain all the important considerations in eliminating<br />

child labour.<br />

The C182 was preceded by at least two other related conventions by the ILO that shed light on its<br />

interpretation and intention. Convention 138 (1973) on the minimum age of children for certain forms<br />

of labour was the culmination of a long series of conventions on separate sectors (industry,<br />

agriculture, sea, non-industrial, and so forth). As time went by, between 1919 and 1973, the minimum<br />

age was progressively raised. Furthermore, a distinction was made between heavy and light work.<br />

Thus, when C138 was <strong>des</strong>igned, both the higher minimum age and the distinction between heavy and<br />

light work were incorporated.<br />

The importance of education was also included in C138. The rule that was laid down in Convention<br />

60 on Industrial labour, which, however, did make it into C138 is that children that had not finished<br />

primary school should not be employed, even if they were above the age of 15. Instead, C138 specifies<br />

that the minimum age cannot be lower than that for completion of compulsory schooling, and, in any<br />

case, may not be lower than 15 years. Although schooling is deemed to be important to a child’s<br />

development, an absence of schooling in itself cannot constitute a violation of the ILO conventions<br />

138 and 182.<br />

A flexibility clause is inserted, allowing states ‘whose economy and educational facilities are<br />

insufficiently developed’, to reduce the minimum age to 14 years. Flexibility in this convention, like<br />

other conventions that are related to economic development, is an important issue and often a<br />

prerequisite to signature by developing states.<br />

Under the minimum age, ‘light work’ is permissible. The definition of light work is that it does not<br />

harm the child’s health or development and that it does not reduce a child’s school attendance (article<br />

7). This type of work can be done between the ages of 13 and 15 or 12 and 14 in countries that enact<br />

the flexibility clause.<br />

Sectors in which conventions apply<br />

The conventions cover both people that are employed and people that are self-employed. Article 4<br />

leaves states the possibility to exclude sectors from the minimum age requirement. An often-named<br />

exception is domestic work. But this possibility to exclude can not include work considered<br />

‘dangerous for the health, safety and morals of young persons’. Furthermore, sectors and types of<br />

work can only be excluded from the minimum age requirement if this is argued to the ILO, under<br />

article 2, sub 5, demonstrating that it is necessary, limited and connected to problems in the<br />

application of the convention. Importantly, the conventions apply to all labour that is performed in a<br />

state (or under its flag). The informal sector, where much child labour including the worst forms takes<br />

place, is not excluded from the working of the convention, even though it is difficult to monitor and<br />

control.<br />

A principal question is whether these worst forms of child labour should be considered work or<br />

labour. In earlier conventions, the denomination had always been: exploitation. A number of<br />

delegates felt that by pulling these crimes into the realm of work, it would somehow lose its status as<br />

purely unacceptable and become just another form of labour (ILC, Report IV, 87 th session, 1998 for<br />

Spain and Bolivia; ILC, provisional record, 86 th session, para 45, 118, 132, 134). The ILC acknowledges<br />

this point in its first report to the Conference in 1998 and stresses the need to criminalize and<br />

eradicate the forms of child labour named in the Convention. The ILO maintains that while they are<br />

crimes, they are also forms of economic exploitation and thus within the realm of the ILO to regulate<br />

9

(ILO, Targeting the Intolerable, 1998). The children that are involved in the activities that are named<br />

in C182 are not considered employees, rather as victims of exploitation. Therefore, the ratification of<br />

the convention requires not that employment conditions are adapted, but rather that exploiters are<br />

penalized, as can be read in article 7 sub 1: States Parties shall take all necessary measures to ensure<br />

the effective implementation and enforcement< including the provision and application of penal<br />

sanctions.<br />

A child is not considered to engage in these worst forms of child labour of its own free will. Even if it<br />

is consensual, this is deemed to be the result of the child’s vulnerability (Kooijman in Nesi, Nogler,<br />

Pertile, 2008: 134).<br />

The worst forms of child labour<br />

All forms of slavery or practices similar to slavery<br />

Article 3 sub a of C182 defines: ‘all forms of slavery or practices similar to slavery, such as the sale<br />

and trafficking of children, debt bondage and serfdom and forced or compulsory labour, including<br />

forced or compulsory recruitment of children for use in armed conflict’. This first of the worst forms<br />

of child labour refer to activity that is induced by the use of force or power, or as is stated in its<br />

defining Convention 29 on forced labour: ‘all work or service which is exacted from any person under<br />

the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily’ (ILO,<br />

Report of the Committe on Child Labour, ILC, 87th Session: para 136). Slavery has been previously<br />

defined by the 1926 Slavery Convention to include a ‘servile status’ that comes with debt bondage<br />

and certain forms of women’s and children’s exploitation (League of Nations, 1926; UN, 1953).<br />

Serfdom or debt bondage<br />

There still exist cases of slave relations, where the victims perform forced labour, have no juridical<br />

capacity, are treated as objects and who live in depraved conditions. Not only in Africa, but also in<br />

Latin America and Asia exist the practice of rural serfdom that is derived from the absolute<br />

ownership of land by conquerors, who distribute it to peons in exchange for services and income<br />

(ILO, Stopping Forced Labour, 2001). Although slavery and serfdom can be a condition that a child is<br />

born into, children are made dependent in order to exploit them still. Trafficked children that were<br />

forced into prostitution report the use of physical and emotional violence in order to perform without<br />

complaints. 2<br />

Debt bondage is another form of forced labour. It presupposes a debt on the part of the victim, or a<br />

form of ‘rent’ for tenancy, and this is used to oblige the person to continue working until the debt has<br />

been paid off. Children can be affected whey they are pledged by their parents to repay a hereditary<br />

or other debt. On the other hand, a debt may amass because of the service of a trafficker, in order that<br />

the labour that a child performs may be used as a way to repay the trafficker (Bureau of the Dutch<br />

Rapporteur on Human Trafficking, 2009).<br />

Both the ICESCR and the CRC address the issue of slavery and slavery like practices, though their<br />

influence is not deemed to be very great (Fodella in Nesi, Nogler and Pertile: 213). This is in contrast<br />

to the ICCPR, where the Human Rights Committee and currently, the Human Rights Council, has<br />

issued concluding observations on slavery, the prohibition of which is absolute (article 4) and forced<br />

labour (only allowed as a penalty). The monitoring mechanism of the ICCPR, mentioned above,<br />

2 Nigerians being trafficked to The Netherlands have reported being threatened through the use of voodoo in<br />

order to keep them in the prostitution. The use of violence is reported in other studies, for example, Tanzanian<br />

organization Kivulini reporting on trafficking for sexual purposes in 2006.<br />

10

provi<strong>des</strong> for individual redress as well as inter-state complaints, thereby strengthening the<br />

application of the rights much.<br />

Forced recruitment of children for use in armed conflict<br />

Convention 182 as well as the Optional Protocol to the Convention for the Rights of the Child do not<br />

make a distinction between a child being forcibly recruited for work as a child soldier and any other<br />

(non-combatant) work. The previous Genevan Convention did make this distinction, but since it is<br />

virtually impossible to control what activities soldiers perform in practice and due to the fact that<br />

involving children in armed conflict was as a rule unacceptable, the wording became more general<br />

and inclusive of all activities.<br />

Voluntary recruitment is not ruled out in either of the conventions, and this is allowed from age 17<br />

on, on the premise that children under 18 do not partake in combatant tasks. It stands to reason that<br />

the obligation to prevent the underage children from entering the battle must be clearly demonstrated<br />

through the policy that is in place to train and deploy soldiers.<br />

The sale and trafficking of children<br />

The sale and trafficking of children is currently receiving increased attention, and because of that, the<br />

magnitude of the problem is becoming understood. It affects millions of children, who are trafficked<br />

internationally, but it appears that a multiple of this amount is being trafficked internally. Trafficking<br />

is a precursor to many forms of child exploitation, such as prostitution or child soldiers.<br />

This research does not view trafficking as a separate occurrence, it has only taken note of trafficking<br />

in relationship to other phenomena. This is because the research would have been expanded in scope<br />

indefinitely, become involved with cross-border phenomena that would be difficult to oversee and<br />

hence, make any conclusions on. Therefore, the situations that trafficking is named are limited, as is<br />

the extent to which trafficking is <strong>des</strong>cribed.<br />

In this sense, the most important international legal instrument is the Palermo Protocol of 2000, or, the<br />

Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons Especially Women and Children,<br />

supplementing the United Nations Convention on Transnational Organized Crime. This protocol<br />

considers trafficking to consist of two elements: (1) the recruitment, transportation, transfer,<br />

harboring or receipt of children with (2) the purpose of subjecting them to any form of exploitation,<br />

including prostitution or sexual slavery and servitude or the removal of organs. A third element, the<br />

use of coercion or deceit, is necessary to establish the crime with adults; this is not the case with<br />

children.<br />

Prostitution, Pornography and Pornographic Performances<br />

The Convention for the Rights of the Child seeks to eradicate sexual exploitation of children. In<br />

Convention 182, this economic exploitation is recognized as a worst form of child labour and defined<br />

as follows: the ‘use, procuring or offering of a child for prostitution, for the production of<br />

pornography or for pornographic performances’.<br />

The sexual exploitation of children can take the form of local exploitation, likely to form the bulk of<br />

the cases of exploitation, but sex tourists may visit a country in order to satisfy their sexual <strong>des</strong>ires<br />

with children. A related category to sex tourists is the traveling businessmen, who do not travel<br />

primarily to satisfy their sexual <strong>des</strong>ires but may use the opportunity that they have while traveling to<br />

do so. Children may also be trafficked nationally or internationally to places where they can be<br />

exploited. Circulating pornography with child content is also covered under the convention, even<br />

though there is no direct contact between the ‘consumer’ and victim.<br />

11

Prohibiting prostitution is required for all children under 18, regardless of the legal age limit of<br />

adulthood or maturity. Pimping, procuring or inducing children into prostitution also needs to be<br />

penalized. These prohibitions only work in a system that regularly controls the age of persons who<br />

work as a prostitute and that actively regulate prostitution including pimps. This is not always the<br />

case, such as when police round up prostitutes but only to fine or imprison them, not to question<br />

them regarding their pimp or their age (Stöpler, 2009b and 2007 on Tanzania and Cambodia).<br />

Furthermore, laws can be <strong>des</strong>igned that penalize indirect profiting and facilitating, such as operating<br />

a bar or other establishment where child prostitution takes place (The example provided by<br />

Kooijmans in Nesi, Nogler and Pertile, 2008 is of the Philippines, Republic Act No. 9231 (Act on the<br />

Special Protection of Children Against Child Abuse, Exploitation and Discrimination of 2003), art. 5).<br />

The persons that sexually exploit children under 18 need to penalized. These legal provisions often<br />

exist, albeit that the age of consent limit may be below 18 (in The Netherlands for example, it is 16)<br />

but this does not affect the justiciability of those who perform transactionary sexual acts with a child.<br />

A difficulty that needs to be considered is how much knowledge can be expected from a customer:<br />

can a customer be expected to check identification papers or be able to guess the age of prostitutes<br />

who are, for example 17 instead of 18 Different states deal with this issue differently, but it should be<br />

clear that the enforcing of the age limit is challenging.<br />

Child pornography or pornographic performances<br />

The possession (including through cache memory of a downloaded image in one’s computer),<br />

distribution, production or aid to any of these, of images of children involved in any sexual activity is<br />

prohibited. Both the Optional Protocol to the Convention for the Rights of the Child and Convention<br />

182 of the ILO prohibit the procurement or offering, that is the activity of pimps or middle men. The<br />

pictures of children do not necessarily need to be real in order to fall under the prohibition. It is up to<br />

states to decide how extensively they want to prohibit child pornography; many states have gone so<br />

far as to criminalize any and all images of children, whether they are animated, manipulated or real<br />

(For example, Greece, New Zealand and The Netherlands).<br />

Pornographic performances with children are to be penalized, as well as advertising for them. Each<br />

implementing state will need to consider whether it wants to forbid offering per se or whether it only<br />

forbids it when real children are offered, such that a venue that advertises child pornography but<br />

offers adults, would not be breaking the law on child pornography.<br />

The use of children for illicit activities<br />

The use, procuring or offering of children for illicit activities, in particular involving the production or<br />

trafficking of drugs such as defined in relevant international agreements is defined as one of the<br />

worst forms of child labour. The word illicit has been chosen instead of illegal and the reference to<br />

international agreements made in order to avoid being dependent on national legislation regarding<br />

the production and transport of drugs (Noguchi in Nesi, Nogler and Pertile: 153).<br />

Under this article, it is not entirely clear which activities are meant, although it is clear that it is<br />

broader than activities involving drugs, since the recommendation 190 also mention the carrying of<br />

firearms. Another suggestion is to criminalize the use, offering or procuring children for illegal<br />

activities. Forced begging has been brought to the attention of a number of states, while begging, nor<br />

the activities of children are meant to be criminalized, but rather the exploitation of these children<br />

(Belgium, Belarus, Fiji, Kazakhstan and Trinidad and Tobago received comments from the CEACR for<br />

<strong>des</strong>igning legislation against using children in begging).<br />

Hazardous work<br />

While the previous types of the worst forms of child labour are worst forms by definition, hazardous<br />

work is work ‘which by its nature or the circumstances in which it is carried out, is likely to harm the<br />

12

health, safety or morals of children.’ This definition leaves much open to interpretation and lacks the<br />

clarity of the other types of the worst forms of child labour. It is this type of child labour that the<br />

worst forms of child labour are most often associated with however, encompassing activities like<br />

mining, working with sharp objects, poisons and pestici<strong>des</strong>, long hours or night work, heavy loads<br />

and extreme temperatures.<br />

There are many types of work that fall under the present definition, and in the accompanying<br />

recommendation, a number of sectors are named that are likely to lead to worst forms of child labour.<br />

It is up to States Parties to make a choice in defining sectors and types of employment that they find<br />

unacceptable for children to work in. At the same time, it is also possible for governments to exempt<br />

the work done at home on farms, as long as parents are in control of the working conditions and able<br />

to protect their children from harm (ILC, Report of the Committee on Child Labour, 87th Session).<br />

The list that is established by the States Parties define which types of labour are hazardous and<br />

therefore unacceptable for children under 18. To a certain extent, Convention 182 is a specification<br />

and a complement to Convention 138, which raises the minimum age for labour. The above named<br />

mechanism for grading labour and associating that with specific age limits returns in this particular<br />

article that is reserved for the heaviest category of work. Work that is less heavy will fall under<br />

Convention 138, but not under 182. Since there is not a standard of hours that defines heavy labour,<br />

the ILO has been working with its own definition, which is 43 hours and above. In other words,<br />

children from 15-17 can work up to 42 hours per week. It also uses standards from other agreements<br />

to define hazardous work: night work, working as a trimmer or stoker, working as a fisherman under<br />

certain conditions, manual transport of heavy loads, working with radiation, benzene, white lead in<br />

paint, anthrax, white phosphorus, asbestos, specific chemicals and carcinogenic substances or agents<br />

as well as air pollution, noise and vibration. 3<br />

The obligation in article 4, to define the forms of hazardous work that are to be included in forms of<br />

labour that are unacceptable, is a procedural one. The Committee of Experts on the Application of<br />

Conventions and Recommendations (CEACR) cannot force a state to take up any type of work that is<br />

not on the list that the States have devised; the Committee of Experts can and does make suggestions,<br />

however (CEACR, Individual Direct Request concerning C182: Kuwait, 2004, Panama, 2004 and 2006;<br />

Ireland, 2005).<br />

As a result, different states come up with different lists. One aspect that is often missed in the list<br />

regards the moral harm, whereas health and safety are most often seen. The moral hazards, the<br />

Committee of Experts suggest, lie in the threat of violence, psychological abuse and sexual abuse<br />

(Beqiraj in Nesi, Nogler and Pertile: 194-197).<br />

Implementing the list leads to the difficulty of monitoring and control. It is not unusual to find that<br />

the government does not consider itself to be responsible for all of the children: children working<br />

without a contract, that are self-employed or in the ‘informal’ sector (Stöpler, 2009b; CEACR<br />

Individual Direct Requests of Mongolia, Iran, Benin, Ethiopia, Cameroon, Algeria, Chad,<br />

Switzerland). It appears that much of law is oriented not so much toward children, but toward the<br />

contractual agreements. 4 The enforcement of these provisions, especially as they may not solely<br />

3 Convention concerning the Night Work of Young Persons Employed in Industry, no. 6; Convention fixing the<br />

Minimum Age for the Admission of Young Persons to Employment as Trimmers or Stokers, No. 15;<br />

Convention concerning the Minimum Age for Admission to Employment as Fishermen, No. 112; Convention<br />

concerning the Use of White Lead in Painting, No. 13. The other norms named such as radiation are understood<br />

to be inherently hazardous.<br />

4 Even Bequraj in Nesi, Nogler and Pertile states that the law does not reach into the informal sector, which is<br />

certainly not true of human rights law, though it may be so for contract law.<br />

13

depend on police force, but also on labour inspection, may be seriously understaffed (Stöpler, 2009b;<br />

ILO, Targetting the Intolerable, 1998).<br />

Requirements of international instruments<br />

Convention 182 calls on governments to prohibit the worst forms of child labour and provide<br />

penalties (article 7, sub 1). It also requires governments to monitor the implementation of policy and<br />

law to eliminate the worst forms of child labour (article 5). The requirement that States <strong>des</strong>ign and<br />

implement time-bound programs to ensure the reduction of the worst forms of child labour set it<br />

apart from other conventions, namely the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC).While the<br />

content of article 34 of the CRC aims for the same goals as C182, the CRC does not make specific<br />

requirements for the realization of these goals. That makes the threat of a symbolic ratification<br />

greater. Since the CRC does not make clear how the goals are to be achieved, the rights and duties are<br />

insufficiently concrete to be legally enforceable. This is not the case with C182. It is controllable<br />

whether legal provisions have been made, monitoring systems developed.<br />

There is less clarity on the requirements of international cooperation called for in article 8. It does give<br />

concrete examples of programs, but it does not make any requirements on the outcome of these<br />

programs, which is included in the national programs.<br />

Obligations for States not Party to Convention 182 or Convention 138 are less stringent but not absent.<br />

This is due to the fact that in 1998, the ILO accepted the Declaration on Principles and Rights at Work.<br />

The fundamental principles are Freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to<br />

collective bargaining, Elimination of all forms of forced or compulsory labour, Effective abolition of<br />

child labour, the Elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation.<br />

The Declaration makes it clear that these rights are universal, and that they apply to all people in all<br />

States - regardless of the level of economic development. There is specific attention for migration and<br />

other vulnerable groups. It further establishes that economic growth alone is not enough to ensure<br />

equity, social progress and to eradicate poverty.<br />

The reporting procedure under the Declaration is supported by a follow-up procedure. Member<br />

States that have not ratified one or more of the core Conventions are asked each year to report on the<br />

status of the relevant rights and principles within their borders, governments are extolled to clarify<br />

their needs and opportunities for progress. These reports are reviewed by the Committee of<br />

Independent Expert Advisers. In turn, their observations are considered by the ILO's Governing<br />

Body.<br />

A brief conclusion to the legal section can suffice to clarify that the international conventions<br />

concerning child labour – notably conventions 138 and 182 are to be used for this study – have acted<br />

as legal mileposts that have created considerable pressure for states to conform to the codified<br />

provisions. These provisions have not been accompanied by enforcement measures and at times, the<br />

provisions to be enforced are not well-understood by the governments that should comply to them.<br />

Finally, governments that have not ratified conventions 138 and 182 are not free to allow child labour,<br />

even legally, since they are bound by the principles of the ILO. This study is intended to demonstrate<br />

how, in a few countries across the world, child labour affects children and how governments,<br />

international organizations and non-governmental organizations (NGO’s) try to eradicate child<br />

labour.<br />

14

Bibliography<br />

Bureau of the Dutch Rapporteur on Human Trafficking. 2009. Seventh Report on Trafficking in The<br />

Netherlands. The Hague.<br />

Committee on Economic Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), General Comment no. 3, The Nature of<br />

States Parties Obligations, Fifth session, 1990, E/1991/23.<br />

Committee on the Rights of the Child. General Comment no. 4. 2003. Adolescent health and development<br />

in the context of the Convention on the Rights of the Child. CRC/GC/2003/4<br />

Convention on the Rights of the Child. Adopted and opened for signature, ratification and accession<br />

by General Assembly resolution 44/25 of 20 November 1989. Entry into force 2 September<br />

1990, in accordance with article 49.<br />

Convention concerning the Night Work of Young Persons Employed in Industry, no. 6 (1919).<br />

Convention fixing the Minimum Age for the Admission of Young Persons to Employment as<br />

Trimmers or Stokers, No. 15 (1921).<br />

Convention concerning the Minimum Age for Admission to Employment as Fishermen, No. 112<br />

(1959).<br />

Convention concerning the Use of White Lead in Painting, No. 13 (1921).<br />

International Labour Conference, Provisional Record No. 19, 86 th Session (1998).<br />

International Labour Conference, Report IV (2A), Child Labour, presented at the 87 th Session of the<br />

Conference for Bolivia and Spain;<br />

International Labour Organization. Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work,<br />

adopted 1998. http://www.ilo.org/declaration/lang--en/index.htm<br />

International Labour Organization International Program against Exploitation of Children. 2005.<br />

Resources and Processes for Implementing the Hazardous Child Labour Provisions of ILO Conventions<br />

Nos 138 and 182, Report of the ILO Asian Regional Tripartite Workshop held in Phuket,<br />

Thailand, 11-13 July 2005.<br />

International Labour Organization. 1998. Child Labour: Targeting the Intolerable. Geneva.<br />

International Labour Organization. Stopping Forced Labour, Global Report under the Follow-Up to the ILO<br />

Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work, Geneva: ILO, 2001.<br />

International Labour Organization. Record of Proceedings, Report of the Committe on Child Labour,<br />

ILC, 87th Session, 1999, Geneva.<br />

League of Nations’ Slavery Convention: date of adoption, 25 September 1926; entry into force, 9<br />

March 1927.<br />

Nesi, G. L. Nogler and M. Pertile. 2008. Child labour in a globalized world. Ashgate, Burlington, USA,<br />

Hampshire, England.<br />

15

Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in<br />

armed conflict, 25 May 2000, entry into force 12 February 2002.<br />

Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the sale of children, child<br />

prostitution and child pornography. Adopted and opened for signature, ratification and<br />

accession by General Assembly resolution A/RES/54/263 of 25 May 2000. Entered into force on<br />

18 January 2002<br />

Stöpler, L. 2009b. The Hidden Shame. <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong>, The Hague.<br />

Stöpler, L. 2007. What We Don’t See, Isn’t There. <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong>, The Hague.<br />

16

Bangla<strong>des</strong>h<br />

1. Introduction and background to child exploitation<br />

Seven to twenty million child labourers are estimated to be living in Bangla<strong>des</strong>h. According to the<br />

National Sample Survey of Child Labour by the Bangla<strong>des</strong>h Bureau of Statistics (2002-2003), there<br />

were 7.4 million economically active children aged 5 to 17 years in Bangla<strong>des</strong>h. The real number is<br />

thought to be higher, as the National Sample Survey took school enrolment but not drop-out rates<br />

into consideration. The survey also did not include certain elements of the informal sector (BSAF,<br />

State of Child Rights Bangla<strong>des</strong>h, 2008: 19). An estimated 90 - 95% of working children are active in<br />

the informal sector 5 : 60% in agriculture, 6 77% in the rural informal sector and 16% in the urban<br />

informal sector (BSAF 2008: 19). About 74% of working children are estimated to be boys (BSAF 2008:<br />

19). Despite a number of efforts and successes, there are no employment sectors in Bangla<strong>des</strong>h that<br />

can be accurately <strong>des</strong>cribed as child labour free. 3<br />

The overriding sentiment in Bangla<strong>des</strong>h is that child labour is increasing. 4 Factors such as rapid<br />

population growth, increasing poverty and decreasing job opportunities, urbanization and climate<br />

change are <strong>des</strong>cribed as influential. Bangla<strong>des</strong>h is geographically vulnerable, facing increased river<br />

erosion and other consequences of climate change; it is constantly on the brink of disaster. Villages are<br />

more vulnerable to these changes, resulting in high levels of urban migration. The government lacks<br />

the capacity to provide for the growing number of people concentrating into urban areas and so many<br />

of them end up living in horrific slum conditions, with the whole family, including young children,<br />

forced to work just in order to survive. Increasing funds from remittances and a growing economy<br />

and informal sector, partly as a result of the global economic recession, are pull factors creating a<br />

greater demand for cheap labour. Changes within the family structure, including the increasing<br />

prevalence of child neglect are found throughout Bangla<strong>des</strong>h and are pushing some children to the<br />

cities for reasons unrelated to economic necessity. There is a lack of viable alternatives for many of<br />

Bangla<strong>des</strong>h’s children and a lack of awareness of the hazards of many types of work.<br />

Children living and working in the streets of Bangla<strong>des</strong>h’s cities have been identified as a particularly<br />

vulnerable group. There is estimated to be 600,000 street children living on the streets of Dhaka. 5 Both<br />

boys and girls of an increasingly young age - seven is now common – can be found; the average age at<br />

one shelter has gone down from 14 to 11 in recent years 6 . These children have come to Dhaka to<br />

escape poverty or abuse, often after the death of a parent, remarriage leading to abuse or neglect by a<br />

stepparent or simply in search for a means of livelihood and survival. Parents living in villages also<br />

send their children to work in Dhaka, but they often have little knowledge about the conditions their<br />

children end up living and working in. Street children face abuse from police and employers, are<br />

isolated, have no support network and are vulnerable to exploitation and are active in many sectors<br />

of hazardous work 7 . Although there are laws regulating the work done by children, limited<br />

resources, corruption, and a lack of political commitment stand in the way of the effective<br />

implementation of these laws. The low level of education predominant among parents, coupled with<br />

the custom of passing one’s trade onto one’s children, places school well down the list of priorities.<br />

1<br />

Mr. Sharfuddin Khan (ILO), Mr. Hassan (SEEP), BSAF report<br />

6<br />

Mr. Sharfuddin Khan (ILO)<br />

3<br />

Mr. Sharfuddin Khan (ILO)<br />

4<br />

Raja Bhai (SEEP), Ms. Zinnat Afroze (Plan Bangla<strong>des</strong>h), Mr. Sharfuddin Khan (ILO), Mr. Kafil Uddin (BSAF)<br />

5<br />

Mr. Kafil Uddin (BSAF)<br />

6<br />

Mr. Hassan (SEEP)<br />

7<br />

Ms. Zinnat Afroze (Plan Bangla<strong>des</strong>h), Mr. Shamsul Alam (Save the Children Sweden-Denmark)<br />

17

It is still the norm culturally for children to be working, especially in the sectors of domestic work and<br />

agriculture. In fact, the majority of child labour is found within the agricultural sector in Bangla<strong>des</strong>h,<br />

but there are no statistics available indicating how many of these children are involved in hazardous<br />

activities. In agricultural families, it is considered a normal part of the child’s development,<br />

upbringing and household contribution to accompany their parents to work as soon as they are able.<br />

Agricultural labour is not seen as inherently hazardous or harmful to the child’s development.<br />

Domestic labour is another common type of child labour in Bangla<strong>des</strong>h. Because it takes place within<br />

the home, it is widely thought of as appropriate work, including for young children; it is seen as less<br />

strenuous or dangerous than other types of work. For parents, finding domestic work for their child is<br />

a way of ensuring they have a roof over their heads and enough food to eat. Employers believe that<br />

they are helping a poor family out by hiring a child. Many concerned organizations, including the<br />

ILO, are calling for domestic work to be classified as hazardous labour, after all, the work being done<br />

is often inherently dangerous and the working hours extremely long 7 .<br />

Even though child labour is acknowledged and openly discussed as a problem in Bangla<strong>des</strong>h, and<br />

<strong>des</strong>pite the vast amounts of effort and money put into <strong>des</strong>igning and implementing programmes to<br />

address child labour over the years, the recent and rapid changes in population, the climate, society<br />

and the economy are threatening to overshadow successes as the number of vulnerable and exploited<br />

children continues to grow.<br />

2. Law and policy<br />

2006 Labour Act<br />

The Government of Bangla<strong>des</strong>h, through the Ministry of Labour and Employment, has reviewed all<br />

fragmented laws related to child labour with the aim of fixing a uniform age for admission to work<br />

and to prohibit children’s engagement in hazardous occupations. According to the Labour Act of<br />

2006, the minimum working age is 14 years, but rises to 18 years for hazardous work. Light work for<br />

children between the ages of 12 and 14 is defined as non-hazardous work that does not impede<br />

education. 8<br />

There are a number of statutes, which stipulate the minimum age at which children can legally work<br />

in certain sectors. These are:<br />

Mines (Mines Act, 1923): 15 years (with medical certificate of fitness);<br />

Shops and other commercial establishments (Shops and Establishments Act, 1965): 12 years;<br />

Factories (Factories Act, 1965): 14 years (with medical certificate of fitness);<br />

Railways and ports (Employment of Children Act, 1938): 15 years;<br />

Workshops where hazardous work is performed (Employment of Children Act, 1938): 12<br />

years;<br />

Tea gardens (Tea Plantation Labour Ordinance, 1962): 15 years.<br />

(ILO/IPEC: Child Labour and Responses, Overview Note Bangla<strong>des</strong>h (2004))<br />

National child labour policy (draft)<br />

NCLP (Final Draft), completed in 2008, recognizes that child labour deprives children of their basic<br />

rights to enjoy a decent childhood, hampers their physical and mental growth and consequently<br />

retards the <strong>des</strong>ired national development. The short-term goals of NCLP include the:<br />

• elimination of the worst forms of child labour within a specific time frame;<br />

7<br />

Mr. Sharfuddin Khan (ILO)<br />

8<br />

Mr. Sharfuddin Khan (ILO)<br />

18

• development of an adequate legal framework for the protection of child labour; and<br />

• protection of children from exploitation.<br />

The long-term goals focus on the elimination of all types of child labour (Mondal, 2009).<br />

Trafficking<br />

The government prohibits the trafficking of women and children for the purpose of commercial<br />

sexual exploitation or involuntary servitude under the Repression of Women and Children Act of<br />

2000 (amended in 2003)<br />

Forced labour<br />

Article 374 of Bangla<strong>des</strong>h’s penal code prohibits forced labour, but the prescribed penalties of<br />

imprisonment for up to one year or a fine are not sufficiently stringent to deter the offense.<br />

Child prostitution<br />

The Bangla<strong>des</strong>hi penal code prohibits the selling and buying of a minor, under the age 18 for<br />

prostitution in Articles 372 and 373. Prescribed penalties for sex trafficking commensurate with those<br />

for other grave crimes such as rape; conviction means either life imprisonment or the death penalty.<br />

Hazardous sectors<br />

In 1995, the Ministry of Labour and Manpower, together with UNICEF, did a study to identify the<br />

hazardous activities involving children, as <strong>des</strong>cribed below. This study did not culminate in a list of<br />

hazardous work in which children under 18 are not allowed to work (IREWOC, 2009).<br />

Code of conduct for informal sector<br />

A code of conduct for employment in the informal sector has been developed and submitted to the<br />

Ministry of Labour and Employment; approval is pending.<br />

3. Forms<br />

a. All forms of slavery or practices similar to slavery, such as the sale and trafficking<br />

of children, debt bondage and serfdom and forced or compulsory labour, including<br />

forced or compulsory recruitment of children for use in armed conflict<br />

Bonded-child labour exists in Bangla<strong>des</strong>h, but is not visible or generally acknowledged. The<br />

government has a tendency to avoid the use of the term bonded, although this type of exploitation<br />

occurs in shipyards, the dried-fish industry, tea gardens and agricultural and domestic work.<br />

Bonded-child labourers work in isolation under miserable conditions and often without pay. 8<br />

Domestic labour<br />

According to studies supported by ILO and UNICEF in 2005 and 2006, there are more than 420,000<br />

child domestic workers in Bangla<strong>des</strong>h; 148,000 in Dhaka alone. More than 75% of child domestic<br />

workers are estimated to be girls (National Policy on Children (draft) and final report on National<br />

Seminar on HCL in an Urban Informal Economy, ILO/ MoLE/ UNICEF (2007)). Child domestic<br />

workers are thus extremely common in Bangla<strong>des</strong>h. It is part of the tradition and culture to have<br />

domestic help. This type of work is not illegal, nor is it widely seen as inherently exploitative or<br />

negative for a child. In fact, employers of child domestic workers often feel that they are helping a<br />

poor family by taking in one of their children. Despite this, much of the domestic work done by<br />

8<br />

Ms. Wahida Banu (Aparajeyo Bangla<strong>des</strong>h), Ms. Gita (Ain O Salish Kendra)<br />

19

children in Bangla<strong>des</strong>h can be <strong>des</strong>cribed as a form of slavery, and at the very least as hazardous.<br />

Child domestic work has been identified by many relevant organizations as a topic in need of greater<br />

attention 9 .<br />

Child domestic workers are usually from very poor families in rural areas. The youngest age for<br />

workers in Dhaka is estimated to be six, but in northern Bangla<strong>des</strong>h children as young as four already<br />

work 10 . Some of the youngest child workers are orphans or have lost one parent and many have<br />

parents who started work at a young age themselves and, as a result, never attended school. Recruiters<br />

travel to villages specifically in order to find rural children for employers in the cities 11 . Other<br />

children arrive in the cities with sometimes very distant relatives who have found a house to employ<br />

them. Parents do not always know where, or under what conditions, their children are employed. It is<br />

typical for children to be living and working at their employer’s house. They are given time off once a<br />

year during the Eid festival in order to visit their families. 12<br />

Domestic work takes place behind closed doors and in isolation, leaving child domestic workers very<br />

vulnerable and hard to reach, as well as making this kind of exploitation extremely difficult to<br />

monitor or prevent. Child domestic workers handle dangerous equipment such as irons and sharp<br />

knives, carry heavy loads, work on unsecured roofs or balconies and work very long hours,<br />

sometimes from five in the morning until midnight 13 . Their salary ranges from room and board to<br />

about 2000 taka or € 21 per month, with an estimated average around 500 to 1000 taka per month.<br />

Typical tasks for child domestic workers include washing the dishes, doing the laundry, cleaning the<br />

house, cooking, shopping, crushing spices and looking after younger children. The nature and<br />

circumstances of the work leaves these children vulnerable to abuse; verbal, physical and even sexual<br />

abuse of child domestic workers is common. A significant number of these children run away from<br />

their abusive situations and end up living on the streets. 14<br />

In addition to the hazardous and remote nature of domestic work, it often takes on the form of<br />

bonded labour in Bangla<strong>des</strong>h 15 . It is common for the children themselves to be unpaid, as their<br />

earnings are paid directly to their parents. Girls commonly work for many years receiving no<br />

payment other than shelter and food. In return, the employers promise to cover her marriage<br />

expenses when the time comes. Furthermore, child domestic workers have little or no freedom of<br />

movement or free time.<br />

Dried-fish industry<br />

The fishing industry in the coastal areas of Bangla<strong>des</strong>h is known for its use of bonded child labour 16 .<br />

All of the child labour in the dried-fish industry in these areas is said to be bonded or semi-bonded.<br />

Children are recruited from villages for a small payment to their families or for the promise of full<br />

payment after the completion of their task. The children are taken to remote islands around<br />

Dublarchor where they work for approximately four months under harsh conditions and in complete<br />

9<br />

Mr. Kabir (<strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong> Bangla<strong>des</strong>h), Ms. Zinnat Afroze (Plan Bangla<strong>des</strong>h), Ms. Wahida Banu (Aparajeyo<br />

Bangla<strong>des</strong>h), Ms. Gita (Ain O Salish Kendra)<br />

10<br />

Ms. Husni Ara Quashen (Shoishab Bangla<strong>des</strong>h), interviews with domestic workers in Dhaka and Tangail<br />

11<br />

Ms. Husni Ara Quashen (Shoishab Bangla<strong>des</strong>h)<br />

12<br />

Interviews with domestic workers, parents of domestic workers, and employers of domestic workers in Dhaka<br />

and Tangail<br />

13<br />

Mr. Sharfuddin Khan (ILO), Ms. Husni Ara Quashen (Shoishab Bangla<strong>des</strong>h), interviews with domestic workers<br />

in Dhaka and Tangail<br />

14<br />

Interviews with domestic workers in Dhaka and Tangail, interviews with girls at street childrens centre SEEP<br />

in Dhaka, Ms. Husni Ara Quashen (Shoishab Bangla<strong>des</strong>h), Ms. Gita (Ain O Salish Kendra)<br />

15<br />

Ms. Wahida Banu (Aparajeyo Bangla<strong>des</strong>h)<br />

16<br />

Mr. S.R. Chowdhury and Mr. M. Khorshed (Prodipan), Group interview BSAF, Ms. Gita (Ain O Salish Kendra),<br />

Ms. Mahfuza Haque and Ms. Farhana Jesmine (Save the Children UK)<br />

20

isolation. Children are paid less and are more willing to work under slave-like conditions than adults,<br />

but generally the children never receive the full payment that was promised them. A large<br />

proportion, about 80% of Bangla<strong>des</strong>h’s dried fish, is produced here. 17<br />

The Forest Department and Officers have authority on these protected islands. Even though the<br />

dried-fish industry is not allowed to employ children, it is difficult for anyone to gain access to these<br />

isolated and protected areas in order to monitor the situation. The forest officers typically receive<br />

some royalties from the fish sold and so have a vested interest in the production of dried fish. 18<br />

The National Sample Survey of Child Labour reported in 2002 - 2003 that 14,868 children - 12,776 boys<br />

and 2,093 girls - were employed in ocean and coastal fishing. In reality, this number is most likely<br />

larger. (Blanchet, Biswas, and Dabu) estimated in 2006 that the number of workers below the age of<br />

18, involved in the dried-fish industry alone, would surpass this number and, that even within the<br />

dried-fish industry, this number was low. If shrimp production, which allegedly employs thousands<br />

of children, is taken into account, the real number is likely to be a great deal higher.<br />

Health hazards for these children are numerous. The lack of access to safe drinking water or even<br />

fresh water causes excessive amounts of diarrhoea and skin diseases. Children are injured while<br />

cutting trees to build camps, while walking on fish bones and while tying up the fish. Due to the poor<br />

sanitation, small injuries can readily develop into more serious problems. The costly and inadequate<br />

health care on these remote islands means that injured children often go untreated. The children work<br />

long hours and are often under slept, adding to the prevalence of injuries. Moreover, children<br />

frequently drown during cyclones. If they try to escape, they are usually beaten.<br />

b. Involvement of children in prostitution, production of pornography or<br />

pornographic performances<br />

Child prostitution in Bangla<strong>des</strong>h occurs in organized brothels as well as on the streets. There are<br />

children who have chosen this type of work due to poverty and the lack of alternatives, as well as<br />

children that have been forced into prostitution. Child prostitution is connected to domestic work and<br />

internal trafficking. The children of sex workers are a particularly vulnerable group. Sexual<br />

exploitation remains a hidden topic due to the stigma attached to it. Very little is known about the<br />

sexual exploitation of boys.<br />

Scope<br />

There are an estimated 150,000 women and girls involved in commercial sex work; there is however<br />

no reliable data available and no data at all for certain groups, including boys (National Policy on<br />

Children (draft)). The total population of Tangail brothel in northern Bangla<strong>des</strong>h is estimated at 1500,<br />

including 800 active sex workers and a few hundred children 19 . The girls and women working at this<br />

brothel were forced into sex work at as young an age as ten 20 . There are fourteen large-scale brothels<br />

in Bangla<strong>des</strong>h, with an estimated total of 10,000 active sex workers and a total brothel population of<br />

20,000 21 . There are approximately 1900 children living and working with their mothers in the brothels<br />

of Bangla<strong>des</strong>h 22 .<br />

17<br />

Mr. S.R. Chowdhury and Mr. M. Khorshed (Prodipan)<br />

18<br />

Mr. S.R. Chowdhury and Mr. M. Khorshed (Prodipan)<br />

19<br />

Mr. Abdul Hamid Bhuiyan (Society for Social Service)<br />

20<br />

Interviews with sex workers at Tangail brothel<br />

21<br />

Mr. Abdul Hamid Bhuiyan (Society for Social Service)<br />

22<br />

Ms. Wahida Banu (Aparajeyo Bangla<strong>des</strong>h)<br />

21

The road to sex work<br />

In both floating and brothel-based sex work there are middlemen who recruit children into the<br />

profession. These can be children found living on the streets of major cities or from remote rural<br />

areas. These middlemen are often women, who prey on vulnerable children by earning their trust<br />

through acts of kindness and the offer of security and hope. They will promise <strong>des</strong>perately poor<br />

families an opportunity for employment or education for their child, offer lost children help to find<br />

their way home and be kind to abused children. The recruited children then end up in brothels or<br />

under the control of a pimp and are forced to work for, and even give up their earnings to, those who<br />

now control them. These middlemen are a significant problem; they are hard to identify and often<br />

well connected to the police. Even when caught, they are rarely prosecuted for their actions. 23<br />

Peer pressure as well can play a role in leading children from the streets or otherwise into sex work.<br />

They may hear about a way of earning more money from their peers as they struggle to survive on<br />

the streets. They rarely have a full understanding of what the work entails beforehand and they are<br />

all too easily persuaded to visit a sex club or to meet with a client. 24<br />

In order to end up in Tangail brothel, for example, girls have been sold and trafficked from other<br />

areas of Bangla<strong>des</strong>h by relatives, lovers or strangers. They will typically be bonded for the first few<br />

years in order to work off their purchasing price and to cover living expenses. The bonded girls are<br />

kept in the brothel by fear, which is instilled by regular beatings and other forms of physical,<br />

emotional and sexual abuse; drugs; a security boundary around the perimeter of the brothel; and by<br />

having their wages withheld. Usually during this time pregnancies are not allowed and forced<br />

abortions are carried out. After the bonded period is over the girls are free to leave, but in most cases<br />

the shame and social stigma attached to sex work, as well as the relatively high income that they have<br />

become accustomed to, result in the girls staying on to work independently in the brothel. 25<br />

Abuse<br />

Sex work is illegal in Bangla<strong>des</strong>h, so the children working on the streets often face abuse by the<br />

police. Brothels are also officially illegal, but the ones that date back a long time, such as Tangail<br />

Brothel, are tolerated by the local government. As well as the abuse faced at the hands of the police,<br />

middlemen and pimps – all of whom regularly take prostitute’s earnings or force them into sex - girls<br />

face abuse and torture, such as beatings and gang rape by their clients. The clients are usually able to<br />

bribe their way out of prosecution if caught by the police. Older sex workers are also known to abuse<br />

the younger ones. 26<br />

Born into brothels<br />

The children of sex workers, especially of those working in brothels, face a great deal of physical,<br />

mental and sexual abuse and are vulnerable to exploitation within the brothel environment. Both<br />

boys and girls are physically and sexually abused by local boys, the managers and clients of the<br />

brothel and even their own mothers. Stories of very young children chained to the leg of the bed, to<br />

keep them from trouble while the mother is servicing a client, are not unheard of. Beatings by stick<br />

are common and newer methods, such as hitting children with bottles filled with boiling water, so as<br />

to avoid visible marks of abuse, are being devised. Boys are typically neglected; they tend to end up<br />

involved in illicit activities, working as drug carriers within the brothel or as recruiters of new girls<br />

for the brothel. Abuse and neglect is common and, according to the norms of the brothel<br />

environment, are not reported to the police. Hypothetically, a report might lead to an arrest, but<br />

23<br />

Interviews with sex workers at Tangail brothel and at a street children’s centre in Dhaka, Ms. Rafeza (Society<br />

for Social Service)<br />

24<br />

Interviews with sex workers at Tangail brothel and at a street children’s centre in Dhaka<br />

25<br />

Interviews with sex workers at Tangail brothel, Ms. Rafeza (Society for Social Service)<br />

26<br />

Group interview SEEP employees, Ms. Zinnat Afroze (Plan Bangla<strong>des</strong>h)<br />

22

normally bribes are used to appease the situation. Daughters of sex workers are generally pushed into<br />

their mother’s profession in order to earn money for both of them and to ensure the mother’s eventual<br />

retirement. Some girls are raised by pseudo mothers, who have bought them from traffickers to raise<br />

as sex workers and to take care of them once they get too old to work themselves. 27<br />

Being born into a brothel has many consequences for the children of the sex workers. Their lives are<br />

fairly isolated from the rest of society, they have no experiences outside of illegal activities and the<br />

abusive environment of the brothel and they grow up unable to imagine a different life for<br />

themselves. Due to the stigma on their mother’s profession, they face a lot of discrimination and are<br />

not accepted into the wider community. Growing up without a father has further consequences in<br />

Bangla<strong>des</strong>h, as it is necessary to use your father’s name on most official applications and certificates.<br />

This social and structural discrimination makes it difficult for the children of sex workers to enrol into<br />

schools and to find marriage partners. 28<br />