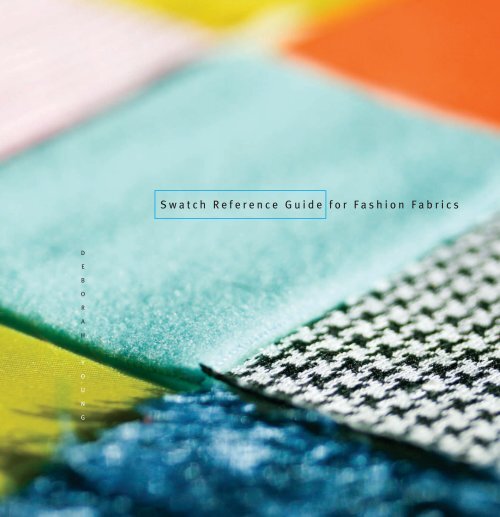

Swatch Reference Guide for Fashion Fabrics - Fairchild Books

Swatch Reference Guide for Fashion Fabrics - Fairchild Books

Swatch Reference Guide for Fashion Fabrics - Fairchild Books

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

D<br />

E<br />

B<br />

O<br />

R<br />

A<br />

H<br />

Y<br />

O<br />

U<br />

N<br />

G<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong> <strong>Reference</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Fashion</strong> <strong>Fabrics</strong>

<strong>Swatch</strong> <strong>Reference</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Fashion</strong> <strong>Fabrics</strong><br />

Young_FM.indd 1 8/31/10 8:19:52 AM

<strong>Swatch</strong> <strong>Reference</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Fashion</strong> <strong>Fabrics</strong><br />

D<br />

E<br />

B<br />

O<br />

R<br />

A<br />

H<br />

Y<br />

O<br />

U<br />

N<br />

G<br />

B F a , M F a<br />

T h e F a s h i o n i n s T i T u T e o F D e s i g n & M e r c h a n D i s i n g<br />

F a i r c h i l d B o o k s<br />

New York<br />

Young_FM.indd 3 8/31/10 8:19:53 AM

Vice President and General Manager, Education and conference division:<br />

Elizabeth Tighe<br />

Executive Editor: olga T. kontzias<br />

assistant acquisitions Editor: amanda Breccia<br />

Editorial development director: Jennifer crane<br />

senior development Editor: Joseph Miranda<br />

creative director: carolyn Eckert<br />

Production director: Ginger hillman<br />

senior Production Editor: Elizabeth Marotta<br />

copyeditor: Jennifer Murtoff<br />

ancillaries Editor: Noah schwartzberg<br />

cover design: carolyn Eckert<br />

illustrations: ron carboni<br />

Text design and layout: Tronvig Group<br />

director, sales and Marketing: Brian Normoyle<br />

copyright © 2011 <strong>Fairchild</strong> <strong>Books</strong>, a division of condé Nast Publications.<br />

all rights reserved. No part of this book covered by the copyright hereon<br />

may be reproduced or used in any <strong>for</strong>m or by any means—graphic,<br />

electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or<br />

in<strong>for</strong>mation storage and retrieval systems—without written permission of<br />

the publisher.<br />

library of congress catalog card Number: 2008943316<br />

isBN: 978-1-56367-728-1<br />

GsT r 133004424<br />

Printed in the United states of america<br />

Mc06<br />

Young_FM.indd 4 8/31/10 8:19:54 AM

v<br />

Table of Contents<br />

Preface xv<br />

Chapter 1 The Textile Cycle: From Fiber to<br />

<strong>Fashion</strong> 1<br />

Chapter 2 Natural Fibers 9<br />

Chapter 3 Manufactured Fibers 17<br />

Chapter 4 Synthetic Fibers 23<br />

Chapter 5 Yarns 31<br />

Chapter 6 Plain Weaves 37<br />

Chapter 7 Plain-Weave Variations 43<br />

Chapter 8 Twill Weaves 49<br />

Chapter 9 Satin Weaves 55<br />

Chapter 10 Pile Weaves 63<br />

Chapter 11 Complex Weaves 67<br />

Chapter 12 Knit <strong>Fabrics</strong> 73<br />

Chapter 13 Specialty Weft Knits 83<br />

Chapter 14 Warp Knits 89<br />

Chapter 15 Minor Fabrications 93<br />

Chapter 16 Dyed and Printed <strong>Fabrics</strong> 101<br />

Chapter 17 <strong>Fabrics</strong> Defined by Finishes 107<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong> Boards<br />

Young_FM.indd 5 8/31/10 8:19:54 AM

vii<br />

Extended Table of Contents<br />

Preface xv<br />

The Objectives of the Text xvi<br />

The Study of Textiles xvi<br />

The Organization of the Text xvi<br />

Constructing the Book xvi<br />

Instructions xvii<br />

Acknowledgments xix<br />

Chapter 1 The Textile Cycle: From Fiber to <strong>Fashion</strong> 1<br />

The Process: Start to Finish 2<br />

In Pursuit of the Perfect Textile 2<br />

Basic Definitions 3<br />

Table 1.1 Basic Textile Definition 3<br />

The Physical Textile Cycle 4<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong>es 1–4 4<br />

The Language of Textiles 4<br />

Textile Per<strong>for</strong>mance Concepts and Properties 4<br />

Activity 1.1 Research Project: New Textiles 7<br />

Chapter 2 Fiber Classification: Natural Fibers 9<br />

Overview: Natural and Manufactured Fibers 10<br />

Cellulose Fibers 11<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong>es 5–9 11<br />

Table 2.1 Properties Common to All Cellulose<br />

Fibers: Cotton, Linen, Ramie, Hemp 11<br />

Table 2.2 Quick <strong>Reference</strong> <strong>for</strong> Individual<br />

Cellulose Properties 12<br />

Protein Fibers: Wool and Silk 13<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong>es 10–17 13<br />

Table 2.3 Minor Hair Fibers 13<br />

Table 2.4 Properties Common to All Protein<br />

Fibers 13<br />

Table 2.5 Properties of Individual Protein Fibers<br />

14<br />

Table 2.6 Comparison of Protein Fiber Properties<br />

14<br />

Activity 2.1 <strong>Swatch</strong> Page: Cotton 15<br />

Young_FM.indd 7 8/31/10 8:19:54 AM

Chapter 3 Fiber Classification: Manufactured<br />

Fibers 17<br />

Manufactured Cellulose 18<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong>es 18–25 18<br />

Manufactured Protein 18<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong> 26 18<br />

Manufactured Mineral 18<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong>es 27–28 18<br />

Table 3.1 Properties of Individual Manufactured<br />

Fibers 19<br />

Activity 3.1 In-Class Activity: Care Label<br />

Contents 21<br />

Chapter 4 Fiber Classification: Synthetic Fibers 23<br />

The Introduction of Synthetic Fibers 24<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong>es 29–33 24<br />

The Burn Test 24<br />

Table 4.1 General Properties of Synthetic Fibers 24<br />

Table 4.2 Properties Specific to Each Synthetic<br />

Fiber 25<br />

Table 4.3 Significance of Properties Common to<br />

All Synthetic Fibers 26<br />

Table 4.4 Burn Categories of Fibers 27<br />

Table 4.5 Burn Characteristics of Fibers 27<br />

Activity 4.1 Lab Activity: Fiber Burn Test 29<br />

Chapter 5 Yarns 31<br />

Yarn Classification 32<br />

Filament Yarns 32<br />

Spun Yarns 32<br />

Novelty Yarns 32<br />

Yarn Twist 32<br />

Table 5.1 Properties of Yarn Twist 32<br />

Yarn Sizing 33<br />

Yarn Count System 34<br />

The Denier System 34<br />

The Tex System 34<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong>es 34–41 34<br />

Activity 5.1 Lab Activity: Yarn Identification 35<br />

Chapter 6 Plain Weaves 37<br />

Understanding Fiber and Fabric 38<br />

Identifying <strong>Fabrics</strong> 38<br />

Criteria <strong>for</strong> Fabric Identification 38<br />

Table 6.1 Basic Weight Categories 39<br />

Organization of <strong>Fabrics</strong> in This Text 39<br />

Plain Weaves 40<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong>es 42–55 40<br />

Activity 6.1 Research Project: Generic Fiber<br />

Project 41<br />

E x T E N d E d T a B l E o F C o N T E N T S<br />

viii<br />

Chapter 7 Plain-Weave Variations 43<br />

Basket Weaves 44<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong>es 56–59 44<br />

Rib Weaves 44<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong>es 60–71 44<br />

Table 7.1 Per<strong>for</strong>mance Expectations of Basket and<br />

Rib Weaves 46<br />

Activity 7.1 <strong>Swatch</strong> Page: Plain Weaves 47<br />

Chapter 8 Twill Weaves 49<br />

Per<strong>for</strong>mance Expectations of Twill Weaves 51<br />

Uneven Twills 51<br />

Even-Sided Twills 51<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong>es 72–83 51<br />

Activity 8.1 <strong>Swatch</strong> Page: Twill Weaves 53<br />

Chapter 9 Satin Weaves 55<br />

Per<strong>for</strong>mance Expectations of Satin Weaves 56<br />

Summary of the Three Basic Weaves 57<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong>es 84–89 57<br />

Table 9.1 Comparison of Basic Weaves 58<br />

Activity 9.1 Weave Comparison Graph 59<br />

Activity 9.2 <strong>Swatch</strong> Page: Satin Weave 61<br />

Chapter 10 Pile Weaves 63<br />

Construction of Pile Weaves 64<br />

Properties of Pile Weaves 64<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong>es 90–95 64<br />

Activity 10.1 In-Class Activity: Closet Raid I 65<br />

Chapter 11 Complex Weaves 67<br />

Crepe <strong>Fabrics</strong> 68<br />

Jacquard Weaves 68<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong>es 96–111 70<br />

Activity 11.1 Research Project: Storybook 71<br />

Chapter 12 Knit <strong>Fabrics</strong> 73<br />

Construction of Knits 74<br />

Table 12.1 Comparison of Weaves and Knits 74<br />

Table 12.2 Stretch Classifications, 18%–100% 75<br />

Preparing Knits <strong>for</strong> Cut and Sew 76<br />

Knit Quality Criteria 76<br />

The Four Basic Knit Stitches 76<br />

Categories of Knit <strong>Fabrics</strong> 77<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong>es 112–127 78<br />

Table 12.3 Comparison of Weft and Warp Knits 78<br />

Activity 12.1 In-Class Activity: Closet Raid II 79<br />

Activity 12.2 Lab Activity: Knit Fabric Analysis 81<br />

Young_FM.indd 8 8/31/10 8:19:54 AM

Chapter 13 Specialty Weft Knits 83<br />

Double Knits 84<br />

Interlock 84<br />

Pile Knits 84<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong>es 128–141 84<br />

Activity 13.1 Application Exercise: Knit <strong>Fabrics</strong> 85<br />

Activity 13.2 <strong>Swatch</strong> Page: Weft Knits 87<br />

Chapter 14 Warp Knits 89<br />

Tricot 90<br />

Raschels 90<br />

Table 14.1 Comparison of Tricot and Raschel<br />

Knits 90<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong>es 142–155 90<br />

Activity 14.1 <strong>Swatch</strong> Page: Warp Knits 91<br />

Chapter 15 Minor Fabrications 93<br />

<strong>Fabrics</strong> Made without Yarn 94<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong>es 156–159 94<br />

Fabric Combinations 94<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong>es 160–161 94<br />

<strong>Fabrics</strong> Made with Yarn 94<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong>es 162–164 94<br />

<strong>Fabrics</strong> Made without Yarn or Fiber 94<br />

Table 15.1 Lace Putups 95<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong>es 165–168 96<br />

Table 15.2 Minor Fabrications 96<br />

Activity 15.1 Lab Activity: Fabric Evaluation by<br />

Weight 97<br />

Chapter 16 dyed and Printed <strong>Fabrics</strong> 101<br />

The Basic Dye Process 102<br />

Stages of Dyeing 102<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong>es 169–171 103<br />

Basic Dye Chemistry 103<br />

Table 16.1 Properties of Dyes and Pigments 103<br />

Special Dye Processes 103<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong> 172 103<br />

Color Management 104<br />

Printed <strong>Fabrics</strong> 104<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong>es 173–187 104<br />

Activity 16.1 Application Activity: Wovens 105<br />

Chapter 17 <strong>Fabrics</strong> defined by Finishes 107<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong>es 188–199 108<br />

Activity 17.1 Application Exercise: Knits 109<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong> Boards<br />

E x T E N d E d T a B l E o F C o N T E N T S<br />

ix<br />

Young_FM.indd 9 8/31/10 8:19:55 AM

xi<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong> Board Contents<br />

Chapter 1 The Textile Cycle: From Fiber to <strong>Fashion</strong><br />

Raw Fiber<br />

1. Cotton<br />

Yarn Constructions<br />

2. Spun yarn<br />

3. Filament yarn<br />

Fabric Construction<br />

4. Muslin<br />

Chapter 2 Fiber Classification: Natural Fibers<br />

Cellulose Fibers<br />

5. Cotton<br />

6. Organically color-grown cotton<br />

7. Flax<br />

8. Ramie<br />

9. Hemp<br />

Protein Fibers: Wool<br />

10. Wool<br />

11. Mohair/Wool<br />

12. Merino<br />

13. Cashmere/Rayon<br />

Protein Fibers: Silk<br />

14. Cultivated Silk<br />

15. Wild Silk<br />

16. Silk Noil<br />

17. Dupioni Silk<br />

Young_FM.indd 11 8/31/10 8:19:55 AM

Chapter 3 Fiber Classification: Manufactured<br />

Fibers<br />

Manufactured Cellulose<br />

18. Rayon ®<br />

19. Bemberg ® Cuprammonium Rayon<br />

20. Modal ®<br />

21. Tencell ® Lyocell<br />

22. Bamboo<br />

23. Acetate<br />

24. Sorona ®<br />

25. SeaTiva ®<br />

Manufactured Protein<br />

26. Soy<br />

Manufactured Mineral<br />

27. Glass<br />

28. Rayon/Metallic<br />

Chapter 4 Synthetic Fibers<br />

29. Nylon<br />

30. Acrylic<br />

31. Polyester<br />

32. Polyester Microfiber<br />

33. Nomex ® Aramid<br />

Chapter 5 Yarn Constructions<br />

Filament and Spun Yarns<br />

34. Single-Spun Rayon<br />

35. Single Multifilament Rayon<br />

36. Two-Ply Spun & Filament<br />

Novelty Yarns<br />

37. Bouclé Jersey<br />

38. Chenille<br />

39. Eyelash Jersey<br />

40. Lamé<br />

41. Herringbone Tweed<br />

Chapter 6 Fabric Structures: Plain Weaves<br />

Balanced Light-weight Sheer Plain Weaves<br />

42. Chiffon<br />

43. Georgette<br />

44. Organza<br />

45. Organdy<br />

Balanced Light-weight Opaque Plain Weaves<br />

46. Challis<br />

47. Voile<br />

48. Batiste<br />

49. Gauze<br />

Balanced Medium-weight Plain Weaves<br />

50. Gingham<br />

51. Madras<br />

52. Chambray<br />

S W a T C h B o a R d C o N T E N T S<br />

xii<br />

53. Shantung<br />

54. Handkerchief Linen<br />

55. Linen Shirting<br />

Chapter 7 Plain-weave Variations<br />

Basket Weaves<br />

56. Canvas/Duck<br />

57. Sportswear Canvas<br />

58. Ox<strong>for</strong>d<br />

59. Ox<strong>for</strong>d Chambray<br />

Rib Weaves: Filament Yarns<br />

60. Taffeta<br />

61. Iridescent Tissue Taffeta<br />

Rib Weaves: Spun Yarns<br />

62. Broadcloth<br />

63. Poplin<br />

Rib Weaves: Spun and Filament Yarns<br />

64. Bengaline<br />

65. Ottoman<br />

66. Faille<br />

67. Crepe Faille<br />

68. Crepe de Chine<br />

Vertical Ribs<br />

69. Pincord<br />

70. Dimity<br />

71. Cotton Ripstop<br />

Chapter 8 Twill Waves<br />

Uneven Twills<br />

72. Light-weight Black Denim<br />

73. Crosshatch Dark Denim<br />

74. Chino<br />

75. Hampton Twill<br />

76. Rayon Gabardine<br />

77. Polyester/Wool Gabardine<br />

78. Cavalry Twill<br />

79. Drill<br />

Even-sided Twills<br />

80. Herringbone<br />

81. Houndstooth<br />

82. Glen Plaid<br />

83. Surah<br />

Chapter 9 Satin Weaves<br />

84. Bridal Satin<br />

85. Charmeuse<br />

86. Crepe-Back satin<br />

87. Antique Satin<br />

88. Flannel-Back Satin<br />

89. Sateen<br />

Young_FM.indd 12 8/31/10 8:19:55 AM

Chapter 10 Pile Weaves<br />

90. Terry Cloth<br />

91. Velveteen<br />

92. Pinwale Corduroy<br />

93. Velvet<br />

94. Crushed Velvet<br />

95. Panné velvet<br />

Chapter 11 Complex Weaves<br />

Slack Tension Weave<br />

96. Seersucker<br />

Dobby Weaves<br />

97. Dobby Shirting<br />

98. Dobby Lining/Filament Dobby<br />

99. Bird’s Eye Piqué<br />

100. Waffle Cloth<br />

101. Momie Weave<br />

Extra-yarn Weave/Supplemental Warp or Weft<br />

102. Extra-Yarn Weave<br />

103. Clip Spot<br />

104. Dotted Swiss<br />

Jacquard Weaves<br />

105. Tapestry<br />

106. Filament Damask<br />

107. Cotton Damask<br />

108. Brocade<br />

Double Weaves<br />

109. Double Weave<br />

110. Double-Weave Satin<br />

111. Matelassé<br />

Chapter 12 Knit <strong>Fabrics</strong><br />

Three Basic Weft-knit <strong>Fabrics</strong>: Jersey<br />

112. Lingerie or Tissue Jersey<br />

113. T-Shirt Jersey<br />

114. Slub Jersey<br />

Jersey Variations<br />

115. ITY<br />

Jersey with Color<br />

116. Fair Isle/Jacquard Jersey<br />

Three Basic Weft-knit <strong>Fabrics</strong>: Rib<br />

117. 1×1 Rib Knit<br />

118. 2×2 Rib Knit<br />

Rib Variations<br />

119. Piqué Knit<br />

120. Thermal Knit<br />

121. Pointelle<br />

122. Slinky<br />

123. Cable Knit<br />

124. Matte Jersey<br />

S W a T C h B o a R d C o N T E N T S<br />

xiii<br />

125. Sheer Matte Jersey<br />

126. Onionskin<br />

Three Basic Weft-knit <strong>Fabrics</strong>: Purl<br />

127. Purl-Knit Fabric<br />

Chapter 13 Specialty Weft Knits<br />

Interlock<br />

128. Polyester Interlock<br />

129. Cotton Interlock<br />

Double Knits<br />

130. Double Jacquard<br />

131. Ponte di Roma<br />

132. Argyle<br />

133. Double-Knit Matelassé<br />

134. Bird’s-Eye Wickaway Piqué<br />

Pile Knits<br />

135. Knit Terry<br />

136. French Terry<br />

137. Sliver Knit<br />

138. Velour<br />

139. Stretch Velvet<br />

140. Microfleece<br />

141. Sweatshirt Fleece<br />

Chapter 14 Warp Knits<br />

Tricots<br />

142. Tricot<br />

143. Shimmer<br />

144. Brushed Tricot<br />

145. Sueded Tricot<br />

146. Satin Tricot<br />

147. Athletic Mesh<br />

Raschel<br />

148. Hex Net<br />

149. Power Mesh<br />

150. Triple Mesh<br />

151. Tulle<br />

152. Raschel Lace<br />

153. Cut Press<br />

154. Fishnet<br />

155. Point d’Esprit<br />

Chapter 15 Minor Fabrications<br />

<strong>Fabrics</strong> Made without Yarn<br />

156. Nonwoven, Nonfusible Interfacing<br />

157. Fusible Tricot Interfacing<br />

158. Imitation Suede<br />

159. Needlepunched Eco Felt<br />

Fabric Combinations<br />

160. Pleather<br />

161. Quilt<br />

Young_FM.indd 13 8/31/10 8:19:55 AM

<strong>Fabrics</strong> Made with Yarn, but not Woven or Knit<br />

162. Embroidered Eyelet<br />

163. Tufted Chenille<br />

164. Venise Lace<br />

<strong>Fabrics</strong> Made without Yarn or Fiber<br />

165. Film<br />

166. Pro-Shell Ultrex ®<br />

167. Leather<br />

168. Suede<br />

Chapter 16 dyed and Printed <strong>Fabrics</strong><br />

Stages of Dyeing<br />

169. Fiber/Stock Dyed<br />

170. Yarn Dyed<br />

171. Piece Dyed<br />

172. Cross Dyed<br />

Printed <strong>Fabrics</strong>: Classics Recognized by Pattern<br />

173. Calico<br />

174. Toile du Jouy<br />

Printed <strong>Fabrics</strong>: Non-Classic Images<br />

175. Direct Print<br />

176. Blotch Print<br />

177. Overprint<br />

Better-Quality Prints<br />

178. Discharge Print<br />

179. Heat-Transfer Print<br />

180. Heat-Transfer Paper<br />

181. Flock Print<br />

182. Velvet Burnout<br />

183. Batiste Burnout<br />

184. Laser Print<br />

Resist Prints<br />

185. Tie-Dye<br />

186. Batik<br />

187. Ikat<br />

Chapter 17 <strong>Fabrics</strong> defined by Finishes<br />

Napping<br />

188. Flannel<br />

189. Flannelette<br />

Emerizing/Sueding<br />

190. Sueded Wickaway Jersey<br />

191. Moleskin<br />

192. Peachskin<br />

Specialized Calendering<br />

193. Glazed Chintz<br />

194. Moiré Taffeta<br />

195. Embossed knit velvet<br />

196. Pleated Jersey<br />

197. Yoryu<br />

198. Plissé<br />

199. Fulled Double Weave<br />

S W a T C h B o a R d C o N T E N T S<br />

xiv<br />

Young_FM.indd 14 8/31/10 8:19:56 AM

xv<br />

Preface<br />

Everyday we touch the subject of this book; we run<br />

our hands over it in our favorite boutique, hang it in<br />

our closets, and drape it on our bodies, and yet the<br />

science behind the textiles we wear continues to elude us.<br />

The intention of this book is to demystify the science and<br />

make it useful <strong>for</strong> anyone in the fashion industry: students,<br />

teachers, stylists, buyers, designers, colorists, in short, <strong>for</strong><br />

just about any fashion professional who can benefit from<br />

a better understanding of how and why fibers and fabrics<br />

work.<br />

The text uses simple, direct language that is not specific<br />

to textile scientists, but rather language that is familiar<br />

to the industry at large. <strong>Fashion</strong> and the apparel trade<br />

require textile science to achieve the appropriate per<strong>for</strong>mance<br />

of the product; however, the science in this book<br />

has a different focus from most textile science texts. The<br />

goal of this book is not to soften the science but to focus<br />

it in a way that is more accessible. Instead of an in-depth<br />

analysis of the molecular structure of a fiber, the text focuses<br />

on the relevant per<strong>for</strong>mance expectations of each fiber<br />

and subsequent elements of textiles.<br />

A solid understanding of basic textile science will assist<br />

professionals in making better choices in fibers and<br />

fabrics <strong>for</strong> their chosen end products. This text strikes the<br />

necessary balance between scientists and designer. It culls<br />

the in<strong>for</strong>mation available to the textile scientist and presents<br />

only the material directly relevant to the designer or<br />

product developer.<br />

This book brings together all of the elements of a<br />

textile together into a common place. With all the in<strong>for</strong>mation<br />

in one location, students can spend less time attempting<br />

to connect the dots and more time applying the<br />

concepts.<br />

Young_FM.indd 15 8/31/10 8:19:56 AM

The Objectives of the Text<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

Create awareness of the diversity of textiles available<br />

Provide a basic working knowledge of textile composition,<br />

function, and application. This will enable the<br />

student to have the in<strong>for</strong>mation necessary to make<br />

in<strong>for</strong>med decisions regarding textiles and to communicate<br />

with industry professionals.<br />

Demonstrate correct use of textile terminology, which,<br />

in itself, is a unique language.<br />

Differentiate between two critical concepts:<br />

- The difference between fiber and fabric<br />

- The difference between weaves and knits<br />

Explain production processes and how they impact<br />

the fabric. This would include potential product per<strong>for</strong>mance,<br />

cost, and selection, based on fiber, yarn,<br />

fabrication, coloration, and finishes.<br />

Differentiate fiber classifications, yarn types, and fabrication<br />

methods, and determine how different fabrics<br />

will per<strong>for</strong>m <strong>for</strong> a specific end use.<br />

Demonstrate the selection of appropriate components<br />

of a garment with respect to compatibility with each<br />

other and with the desired result.<br />

The Study of Textiles<br />

Ultimately the study of textiles will help the designers to<br />

make in<strong>for</strong>med decisions throughout the entire design and<br />

construction process. For example, if you were to make a cotton<br />

blouse, does the fiber content of the thread also have to be<br />

cotton? What about buttons, linings, and interfacings? Polyester<br />

is often both stronger and cheaper than cotton. Would<br />

polyester be a better choice <strong>for</strong> something as seemingly inconsequential<br />

as sewing thread? The polyester thread could<br />

be too strong <strong>for</strong> the garment, and the fabric might tear be<strong>for</strong>e<br />

the seam gives way. Do polyester and cotton have the<br />

same shrinkage rates? Do they have the same heat tolerance<br />

<strong>for</strong> ironing and care? Certainly they are used together often<br />

enough that they must be compatible. But they are not always<br />

compatible. Polyester and cotton actually have dramatically<br />

different care requirements, so fiber mixing must be done<br />

judiciously. This example represents a tiny fraction of the<br />

myriad decisions that you will face in your career. A diligent<br />

study of textiles will give you the knowledge and confidence<br />

to make more in<strong>for</strong>med and reliable choices.<br />

Whatever your place in the manufacturing chain, cost<br />

is a factor. One-third of the cost of a garment or product<br />

is the cost of the fabric. Mistakes in fabric choices can dra-<br />

P R E F a C E<br />

xvi<br />

matically impact the financial bottom line. In fact, one of<br />

the few variables in the cost of a product is the textile itself.<br />

The study of textiles will teach you to shop <strong>for</strong> fabrics appropriate<br />

to a given use, design, or silhouette. In addition,<br />

the in<strong>for</strong>mation gained will assist in quality control recognition<br />

and component compatibility.<br />

The Organization of the Text<br />

This text is organized to follow the natural and logical<br />

sequence of events that occur in the production of a textile.<br />

The first four chapters deal with fibers: natural (cellulose<br />

and protein) followed by manufactured and synthetics. The<br />

next chapter addresses yarn constructions and relevance.<br />

The body of the text is devoted to the identification and articulation<br />

of fabrics by structure and name. The final chapters<br />

address the dyeing, printing, and finishing of fabrics.<br />

Each chapter is punctuated with representative examples of<br />

swatches to re-en<strong>for</strong>ce the subject of the chapter.<br />

Fibers: Natural and Man made<br />

Yarn constructions<br />

Wovens, knits or Minor Fabrications<br />

dyes or Prints<br />

Finishes<br />

End Uses<br />

Constructing the Book<br />

Your first task will be to build this book. One of the things<br />

that you will notice is that text is provided <strong>for</strong> each swatch;<br />

you need only attach the swatches. Although the book is<br />

organized into logical and sequential chapters, the instructor<br />

may well use swatches out of order. It is advised that<br />

you construct the entire book during the first week of class,<br />

mounting all of the swatches at once. This will enable you<br />

to have a complete resource of swatches at your fingertips<br />

<strong>for</strong> the instructor to draw upon to illustrate ideas.<br />

Young_FM.indd 16 8/31/10 8:19:56 AM

Instructions<br />

• Begin by identifying the materials needed:<br />

- Four bundles of swatches: A, B, C, and D<br />

- Small baggie with fiber and two yarns<br />

- <strong>Swatch</strong> boards to mount the swatches<br />

- Pick glass<br />

- Pick needle (not included)<br />

- 1 roll of double-sided tape (not included)<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

The text and swatch boards are shrinkwrapped together.<br />

You have the option of either placing the swatch<br />

boards at the end of your binder, or placing them<br />

next to the accompanying text. All of the swatches are<br />

numbered and correspond to references in the text.<br />

The swatches are bundled in the order that they appear<br />

in the text. Keep the rubber bands on the bundles<br />

until you are ready to assemble the book. Take<br />

swatches from the top of the bundle and keep the<br />

stack face up.<br />

Open the baggie first and attach the fiber to the box<br />

<strong>for</strong> <strong>Swatch</strong> 1 with one-inch of double-sided tape.<br />

Note: If you use exactly one-inch of tape <strong>for</strong> each<br />

swatch, you will not need more than one roll. Place<br />

tape in the middle of the box, and cover the tape<br />

with fiber.<br />

Attach the blue cotton yarn to the box <strong>for</strong> <strong>Swatch</strong> 2.<br />

Attach the white filament yarn to the box <strong>for</strong> <strong>Swatch</strong> 3.<br />

Next, attach the four bundles of swatches sequentially<br />

in the book. Place one-inch of the double-sided tape<br />

horizontally across the top of the swatch box, and<br />

then place the swatch on top of the tape. This way,<br />

you can flip up the swatch to observe and feel both<br />

the front and back.<br />

The swatches are presented in the following bundles:<br />

- 1 bag of fibers and yarns includes <strong>Swatch</strong>es 1-3<br />

- A has <strong>Swatch</strong>es 4–67<br />

- B has <strong>Swatch</strong>es 68–121<br />

- C has <strong>Swatch</strong>es 122–141<br />

- D has <strong>Swatch</strong>es 142–199<br />

Due to availability of some fabrics, there are a few minor<br />

variations in the swatches presented. In all cases,<br />

the swatches have the same character: they share the<br />

same fiber content, yarn construction, count, weight,<br />

stage of dyeing, and finishes. However, the color of<br />

the swatches may vary between kits.<br />

As you apply the swatches to the swatch boards, verify<br />

that the swatch matches the description that is listed.<br />

Rely on fabrics that you already know, such as denim<br />

P R E F a C E<br />

xvii<br />

•<br />

•<br />

or velvet. Check that you are on the right number as<br />

you get to the end of each bundle.<br />

Finally, verify that you have a pick glass in your kit.<br />

Open the pouch and unfold the glass completely.<br />

Look through the glass to the ruler below, and look at<br />

the fabric on your sleeve to get used to the pick glass.<br />

You will use this instrument throughout your study of<br />

textiles, so have it with you <strong>for</strong> every class.<br />

It is often helpful to have a pick needle to assist in<br />

your analysis of fabrics, particularly when it comes<br />

to counts or pick outs (analyzing the structure of the<br />

fabric).<br />

While most facts are provided <strong>for</strong> each swatch in the<br />

text, there instances where the in<strong>for</strong>mation <strong>for</strong> yarn construction<br />

has been eliminated. This corresponds directly<br />

to Activities in the text and requires the student to determine<br />

and fill in the results.<br />

Additionally, the facts provided in the yarn construction<br />

category are simplified. Unless otherwise stated, it is<br />

safe to assume that the yarn type is single (as opposed to<br />

piled). In the case of filament yarns, one can assume multifilament,<br />

unless otherwise indicated.<br />

Some criteria are present only when it is particularly<br />

relevant. Finishes, <strong>for</strong> example is a missing criteria <strong>for</strong> most<br />

fabrics, when it is not an aesthetic or visible finish. This<br />

does not mean that there is no finish on the fabric, we<br />

recognize that most fabrics have a dozen finishes on them<br />

be<strong>for</strong>e they are seen by the consumer; it means that there<br />

is no visible or discernible finish.<br />

Finally, the in<strong>for</strong>mation that is most important or<br />

relevant to the pertinent chapter is often listed first. For<br />

example, in chapters 2-4 when fiber content is being discussed,<br />

fiber is the first item in the list of facts about the<br />

fabric. <strong>Fabrics</strong> are listed first <strong>for</strong> each swatch in the fabrics<br />

chapters (Chapters 6-17). The shift is deliberate to focus<br />

on the subject of the relevant chapter.<br />

Five blank swatch boards have been provided to allow<br />

the student to expand on this fabric reference with their<br />

own fabrics.<br />

Young_FM.indd 17 8/31/10 8:19:56 AM

xix<br />

acknowledgments<br />

An undertaking of this sort is truly a collaborative<br />

project, and there are many people I wish to<br />

thank <strong>for</strong> their patience, encouragement, and support.<br />

I am grateful <strong>for</strong> the support of Carol Shaw Sutton,<br />

who nurtured a love of textiles and helped me to see the<br />

world through fiber eyes. B. J. Sims and Maribeth Baloga<br />

were each essential parts of my education <strong>for</strong> this subject.<br />

Amanda Starling provided the motivation and impetus<br />

<strong>for</strong> this book. Jacob Kaprelian of Uniprints, Peter Krauz<br />

of Trimknits, and Nori Hill of Texollini were each kind<br />

enough to custom produce fabrics <strong>for</strong> this project. Rubin<br />

Schubert and the crew at Ragfinders generously provided<br />

many of the exciting fabrics found in this resource. Anne<br />

Bennion offered support and resources and Tom Young<br />

contributed much needed research. My technical support<br />

team, colleagues, and good friends have been and continue<br />

to be Ben Amendolara, Cassandra Durant Hamm, and<br />

Judy Picetti. I truly could not have put this together without<br />

their insights, support, and faith. I also wish to thank<br />

the <strong>Fairchild</strong> team <strong>for</strong> their initial vision and realization<br />

of the final product. A personal thanks to Martin, Tim,<br />

and Maria at Perry Color Card <strong>for</strong> shepherding the fabrics<br />

through the swatch cutting process. Invaluable assistance<br />

in the assembly of this project was diligently provided by<br />

Mariah Connell and Chad Simpson. I am appreciative of<br />

the patience of the rest of my family during the course of<br />

this three-year project: Amanda, Diana, Mike, Kim, and<br />

Alyssa. Thank you all <strong>for</strong> your generosity, caring, and support.<br />

Most of all, I want to thank Jim Young, who traveled<br />

with me on every wild goose chase, was my personal editor<br />

on this project (and in life), and my heart in this book.<br />

Young_FM.indd 19 8/31/10 8:19:56 AM

<strong>Swatch</strong> <strong>Reference</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Fashion</strong> <strong>Fabrics</strong><br />

Young_FM.indd 21 8/31/10 8:19:56 AM

C<br />

H<br />

A<br />

P<br />

T<br />

E<br />

R<br />

O<br />

N<br />

E<br />

The Textile Cycle: From Fiber to <strong>Fashion</strong><br />

Young_01.indd 1 8/31/10 8:22:10 AM

The development of textiles—spinning, weaving and<br />

sewing—was one of mankind’s earliest technical<br />

achievements, right after taming fire and mastering<br />

stone tools. And after 20-thousand-plus years of textile<br />

history, the basic processes <strong>for</strong> producing textiles have not<br />

changed. Fibers still need to be harvested and spun into<br />

thread or yarn. Those yarns have to be manipulated on<br />

some type of loom structure to create fabric.<br />

To be sure, mechanization in the 1800s and the development<br />

of synthetics in the last century brought new<br />

uni<strong>for</strong>mity and speed to the production process. But it’s<br />

our ingenuity and drive to produce stronger, cheaper, better,<br />

and more beautiful fabrics and fashions that make the<br />

field of contemporary textiles so exciting and diverse. The<br />

number of new fibers and fabrics seems to grow exponentially<br />

every day. It is no longer enough to select a textile<br />

simply <strong>for</strong> its hand, drape, or color. Today’s consumer<br />

wants per<strong>for</strong>mance—fabrics that won’t shrink, wrinkle,<br />

or soil and that will do the dishes on Saturdays. In the<br />

current marketplace we can actually meet most of those<br />

demands. Although we haven’t yet trained textiles to do<br />

the dishes, we do have textiles that will allow you to accomplish<br />

this task in your favorite sweater, without worrying<br />

about staining. Making appropriate fabric choice<br />

requires a thorough knowledge of the science of textiles.<br />

Understanding the hygroscopic, thermoplastic, electrical<br />

retention, or hydrophobic qualities of a fiber or fabric is<br />

essential <strong>for</strong> product developers, apparel manufacturers,<br />

stylists, and fashion designers alike. And if the preceding<br />

sentence sounded a little too technical to you, don’t worry:<br />

you will soon be “speaking textile” too!<br />

The Process: Start to Finish<br />

This text begins with the smallest part of a textile—fiber<br />

—and follows the textile cycle through to the final step,<br />

finishing. With increasing demand <strong>for</strong> more versatile and<br />

functional fabrics, finishing and care have become major<br />

areas of interest within the textile world, unlimited in their<br />

commercial potential. For example, one segment of the<br />

textile industry is devoted to fibers and finishing processes<br />

that resist stains. In their search <strong>for</strong> more stain-resistant<br />

fabrics, researchers have developed textiles that have superior<br />

color retention—even if the color happens to be a<br />

stain. It is an interesting paradox that once a stain has managed<br />

to get past the finish and into the fibers of the fabric<br />

itself, it becomes more difficult to eliminate. Stain removal<br />

may not be the most exciting segment of the industry, but<br />

when you have spilled ink on your sister’s favorite shirt,<br />

it certainly becomes a compelling subject. (Hairspray will<br />

usually remove that ink and get you out of trouble.) This<br />

S w a t c h R e f e R e n c e G u i d e f o R f a S h i o n f a b R i c S<br />

2<br />

and other new developments in textile science are moving<br />

the textile industry into fascinating new realms.<br />

In Pursuit of the Perfect Textile<br />

As visually stimulating and tactile as textiles are, they are<br />

even more exciting from a technological perspective. Consumers<br />

want high per<strong>for</strong>mance and low maintenance; they<br />

want textiles that can do tricks. The field is an exciting<br />

frontier. Space exploration, military and medical research<br />

programs, and, of course, the technology industries have<br />

driven some of the most startling innovations in textile<br />

science. Although not directly inspired by, or created <strong>for</strong>,<br />

the fashion industry, these innovations trickle down to the<br />

world of couture. All it takes is a little creative thinking to<br />

make the leap from battlefield military to fashion couture.<br />

Savvy designers use these new developments to meet the<br />

market demand <strong>for</strong> better, unique products.<br />

For example, the military has developed textiles that<br />

interface with the Global Positioning System (GPS) to<br />

keep track of people. Think of the possibilities. You could<br />

track your children’s whereabouts or even LoJack ® your<br />

spouse! The military has also developed textiles that make<br />

a person appear invisible and shoes that can help one jump<br />

20-foot walls. After the jump however, a 6-hour recharge<br />

is required be<strong>for</strong>e you can jump back out of enemy territory!<br />

(You might wish to take a spare battery!) Imagine<br />

amazing your friends on a basketball court! On a more<br />

serious note, there are textiles with sensors that will detect<br />

the amount of blood lost in a person wounded in the field,<br />

perhaps to determine the viability of a rescue ef<strong>for</strong>t. And<br />

we have textiles that stiffen to act as a splint when necessary<br />

<strong>for</strong> combat injuries as well as those that can dispense<br />

antibiotics.<br />

But military researchers are not alone on the front<br />

lines of textile development today. The medical field is<br />

also producing advancements, like sensors that record and<br />

transmit to your doctor in<strong>for</strong>mation such as heart rate,<br />

blood pressure, and insulin level. Fuji Spinning Company<br />

in Japan has developed a shirt that provides your recommended<br />

daily allowance of vitamin C. Through a process<br />

called microencapsulation, your body slowly absorbs the<br />

medication transdermally (through the skin), just by wearing<br />

the shirt. The shirt continues to administer medication<br />

through as many as 30 to 40 washes. Using the same<br />

technology, one could add many different medications to<br />

a garment. Consider a scarf that provides relief <strong>for</strong> headaches,<br />

gloves <strong>for</strong> arthritis sufferers, or a special shirt <strong>for</strong><br />

Alzheimer’s patients. What happens when these garments<br />

become mainstream technology? Will you need a prescription<br />

<strong>for</strong> your clothes? Will your dress have an expiration<br />

Young_01.indd 2 8/31/10 8:22:10 AM

date? Will there be a black market <strong>for</strong> medicated underwear?<br />

These are fascinating possibilities, but they raise<br />

some provocative ethical questions as well.<br />

In another example of fiber-<strong>for</strong>ward thinking, researchers<br />

are experimenting with spider silk because of its<br />

extreme strength. Spider silk is so strong that if you were<br />

to spin a strand of yarn the diameter of a pencil, it could<br />

stop a 747 in flight. In manufacturing, fiber strength is<br />

critical because the stronger the fiber, the less is needed<br />

<strong>for</strong> a particular use. Spider silk could replace other fibers<br />

to make bulletproof garments—not just vests, but whole<br />

garments—that cover the entire body and that are both<br />

lighter in weight and stronger.<br />

To date, the cultivation of spider silk has been problematic<br />

because the spiders will not cooperate. Unlike silkworms,<br />

spiders are territorial, and they recycle their proteins<br />

(that is, eat their webs), which is the equivalent of packing<br />

up their tents, when they move on. Researchers have had<br />

to get creative in the cultivation of spider silk. Experiments<br />

are being done in cross-breeding spiders with potatoes,<br />

corn, and even goats. Yes, there exists a herd of spider-goats<br />

that produce milk that provide us with really strong fibers.<br />

This is not the future of textiles; this is the present.<br />

Here are some other high-per<strong>for</strong>mance textiles that<br />

are pushing the envelope of textile technology:<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

Textiles that are perfumed with your favorite fragrance.<br />

The perfume lasts through 30–50 launderings.<br />

Antibacterial textiles (no bacteria means no odor).<br />

You can work out all day and go directly on a date!<br />

Shirts with living bacteria that will eat any spills or<br />

perspiration. The effect is a self-cleaning shirt. But because<br />

the bacteria are live, they must be fed regularly,<br />

so although you may not have to wash this shirt, you<br />

might have to feed it!<br />

t h e t e x t i l e c y c l e : f R o m f i b e R t o f a S h i o n<br />

3<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

•<br />

Textiles that change color with temperature—or that<br />

change color and pattern with your mood (remember<br />

mood rings?). This is also being done with wallpaper<br />

(it changes pattern or color according to one’s<br />

whim).<br />

Textiles that change color with the presence of odorless<br />

pesticides or gases—great <strong>for</strong> detecting these dangers<br />

in your children’s play areas.<br />

Textiles that adjust to your body temperature, cooling<br />

you when hot, warming you when cold. Using Thermocule<br />

technology, there are sheets that do just that<br />

so that you do not need to throw the covers on and<br />

off all night. These sheets read your body temperature<br />

and self-regulate.<br />

Hoodies with cell phones or MP3 players built directly<br />

into a cuff or the hood.<br />

A “smart bra” that turns into a sports bra by increasing<br />

its support as you begin to run and then relaxing<br />

when you relax.<br />

T-shirts that play movie trailers or short videos across<br />

your chest.<br />

Window curtains that act as solar panels and power<br />

your house.<br />

Basic Definitions<br />

The first step in understanding textiles is mastering the<br />

vocabulary. Let us begin with some basic definitions<br />

that break down the language into simple terms so that<br />

you can begin speaking the language of textiles today<br />

(Table 1.1).<br />

table 1.1 Basic Textile Definitions<br />

Textile An umbrella term <strong>for</strong> anything that can be made from a fiber or fabric. This is a very general term that could be a<br />

tennis ball cover, a disposable diaper, a dryer sheet, geotextiles (building materials), carpeting, or interior and apparel<br />

fabrics.<br />

Fiber The smallest part of a textile and the raw material of a fabric. A fiber is a hairlike strand very similar to your own hair.<br />

Fibers can be natural or manufactured.<br />

Yarn A number of fibers that are twisted or laid together to <strong>for</strong>m a continuous strand. In order to make fabric, short<br />

fibers must first be made into longer, more usable lengths called yarn. Historically, figuring out how to do this took<br />

humankind a very long time.<br />

Fabric A method of construction or an organization of fibers and yarns. The most common fabric constructions are weaves<br />

and knits, but there are other minor fabrications as well. Garments and other products are made from fabrics.<br />

Dyeing The science of applying color to textiles.<br />

Printing The process of applying color in a design to textiles.<br />

Finish Any process that is done to a fiber, yarn, or fabric to change the way it looks, feels, or per<strong>for</strong>ms. A fabric can be<br />

dramatically changed from its original appearance or per<strong>for</strong>mance by the way it is finished.<br />

Young_01.indd 3 8/31/10 8:22:10 AM

The Physical Textile Cycle<br />

A fiber is the smallest visible part of a textile, a single hairlike<br />

strand. A fiber is either staple or filament in length.<br />

Staple fibers are short—only inches long. All natural fibers<br />

are staple except <strong>for</strong> silk, which is nature’s only filament.<br />

Filament fibers can be miles long and include both manufactured<br />

and silk fibers.<br />

Cotton is a staple, with short fibers, and so is wool.<br />

Acrylic is constructed as a manmade filament and is often<br />

cut to staple length, particularly when it is imitating<br />

wool. Likewise, in a blend such as polyester and cotton,<br />

the polyester would first be chopped into staple lengths <strong>for</strong><br />

easier blending with the staple cotton fibers and <strong>for</strong> an allover<br />

cotton hand, the term <strong>for</strong> how a fiber or fabric feels.<br />

Although filament fibers can be cut to staple length, staple<br />

fibers cannot be made into long filaments.<br />

The following swatches compare the different stages<br />

of a textile, from the raw fiber through the most common<br />

yarn types, spun and filament, and finally to the simplest<br />

fabric made from these fibers.<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong> 1 is a staple cotton fiber. <strong>Swatch</strong> 2 is a yarn<br />

made of cotton staple fibers.<br />

Compare this with <strong>Swatch</strong> 3, which is filament polyester.<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong> 4 is a fabric made of staple fibers. In effect,<br />

these swatches represent the textile cycle: harvest the fiber<br />

from the plant, spin it into a yarn, and use the yarn<br />

to construct the fabric. Note as well the simple difference<br />

in length between the fibers of the two yarns (<strong>Swatch</strong>es<br />

2 and 3). Both yarns are unusually large to aid identification.<br />

In Chapter 5, we will further explore these differences<br />

by comparing two fabrics identical in structure<br />

and fiber; one is made of filament fibers and the other is<br />

staple.<br />

[<strong>Reference</strong> <strong>Swatch</strong>es 1–4]<br />

The Language of Textiles<br />

Be<strong>for</strong>e going any further, the core language of textiles<br />

needs to be introduced. This text will allow you to understand<br />

in detail the inherent per<strong>for</strong>mance properties<br />

of each fiber, yarn, and fabric construction. Familiarity<br />

with per<strong>for</strong>mance concepts and properties helps designers<br />

to determine the specific advantages and disadvantages a<br />

fabric will bring to its end use. In essence this knowledge<br />

mitigates the possibility of making poor fabric choices <strong>for</strong><br />

a particular garment.<br />

Here is an example: We know that linen wrinkles horribly.<br />

By selecting a particular yarn or fabric construction,<br />

S w a t c h R e f e R e n c e G u i d e f o R f a S h i o n f a b R i c S<br />

4<br />

adding a select finish, or blending fibers, we can easily create<br />

a linen garment that will not wrinkle.<br />

The question is which fiber/fabric is best <strong>for</strong> a specific<br />

purpose? This will be answered in part by studying the<br />

following five per<strong>for</strong>mance concepts: durability, com<strong>for</strong>t,<br />

care, appearance, and safety. The per<strong>for</strong>mance of any given<br />

textile is determined by the properties of the fiber, yarn,<br />

and fabric; every component of the construction of a fabric<br />

(fiber, yarn, and so on) inherently has these properties.<br />

In the chapters to come, these per<strong>for</strong>mance concepts will<br />

be extended to all the components of fabric construction.<br />

In this way, you will learn to create fabulous garments that<br />

per<strong>for</strong>m beautifully.<br />

Textile Per<strong>for</strong>mance Concepts and Properties<br />

Per<strong>for</strong>mance concepts relate to the measure of a textile’s<br />

ability to per<strong>for</strong>m in the final product. These concepts include<br />

durability, com<strong>for</strong>t, care, appearance, and safety.<br />

Properties of Durability<br />

Durability is the measure of a textile product’s ability<br />

to resist stress and serve its intended use. (Each criterion<br />

can be measured in a textile lab.)<br />

• Abrasion resistance: The ability of a fabric to withstand<br />

rubbing without wearing a hole in the surface.<br />

• Pilling: The <strong>for</strong>mation of tangled fibers on the surface<br />

of the fabric. Pilling is also caused by rubbing but<br />

with a different end result.<br />

• Cohesiveness: The ability of fibers to cling together.<br />

Only relevant <strong>for</strong> yarn spinning. Usually provided by<br />

crimp.<br />

• Feltability: The ability of fibers to matte together to<br />

<strong>for</strong>m a fabric.<br />

• Elongation: The degree to which a fiber may be<br />

stretched without breaking; the amount of give in a<br />

fabric. Growth can be a problem in a fabric.<br />

• Elasticity: The ability of a fiber to stretch and recover<br />

(return to its original size and shape after stretching).<br />

• Elastomericity: The ability of a fiber to stretch 100<br />

percent and recover.<br />

• Dimensional stability: The ability of a fiber to retain<br />

a given size and shape through use and care. Relates<br />

to shrinkage.<br />

• Strength-tenacity: The ability of a fiber, yarn, or fabric<br />

to resist stress.<br />

Young_01.indd 4 8/31/10 8:22:11 AM

C<br />

H<br />

A<br />

P<br />

T<br />

E<br />

R<br />

S<br />

I<br />

X<br />

Plain Weaves<br />

Young_06.indd 37 8/31/10 8:27:14 AM

Understanding Fiber and Fabric<br />

The difference between fiber and fabric is one of the most<br />

fundamental concepts in textiles and generally one of the<br />

most misunderstood. Fibers are the basic building materials.<br />

<strong>Fabrics</strong> are the final woven, knit, or other constructions.<br />

Identifying the fiber content is important, but it<br />

does not provide the complete picture of a fabric. Think<br />

of describing a house by calling it wood. While the house<br />

may be built primarily of wood, that description does not<br />

create an adequate representation of the entire structure.<br />

Quite simply, fiber is what the fabric is made of, and fabric<br />

is what fiber is made into.<br />

Understanding the relationship between fiber and<br />

fabric is essential to every textile-related discipline from<br />

product developer to fashion designer. Cotton is a very<br />

common fiber that can be constructed into many different<br />

fabrics, such as calico, denim, and jersey. Yet not all cotton<br />

fabrics are alike in their per<strong>for</strong>mance capabilities.<br />

Silk and satin are often confused; they are not the<br />

same thing. Silk is a fiber, and satin is a fabric. Sometimes<br />

silk is made into satin, but more often than not, satin is<br />

made of rayon, acetate, or even polyester. And silk can be<br />

made into many other fabrics.<br />

Fabric stores often organize their inventory by fiber.<br />

If you ask an employee the name of a fabric, he or she<br />

might tell you it is cotton or silk, while showing you a<br />

jersey or broadcloth. Although this practice is common,<br />

it leaves too much room <strong>for</strong> expensive errors. The fiber<br />

content is not the fabric name. Think of all the cotton<br />

fabrics that you know. Are they interchangeable? If you<br />

decide to make a cotton T-shirt and you order cotton<br />

fabric, could you make this garment if you received cotton<br />

corduroy or cotton batiste? No, and that is why it<br />

is not enough to identify a fabric by its fiber content.<br />

Knowing the fiber content is a good beginning, but <strong>for</strong><br />

people working in the industry, a greater knowledge of<br />

fabric names and their per<strong>for</strong>mance criteria are required<br />

to successfully create a textile product <strong>for</strong> fashion, home,<br />

or industry.<br />

In Activity 3.1 (see page 21), we analyzed the details<br />

of care labels and discovered that they are rather limited in<br />

scope. If a label says cotton, silk, polyester, or rayon, it is<br />

the fiber content that is listed and not the fabric. In fact,<br />

fabric names are not even required on a care label. Does<br />

this mean that fabric in<strong>for</strong>mation is not important? It is<br />

extremely important, as you will soon see.<br />

Review <strong>Swatch</strong> 1 (cotton fibers) and <strong>Swatch</strong> 4 (the<br />

simplest cotton fabric) <strong>for</strong> a reminder of the difference between<br />

fiber and fabric.<br />

S w a t c h R e f e R e n c e G u i d e f o R f a S h i o n f a b R i c S<br />

38<br />

Identifying <strong>Fabrics</strong><br />

How do we identify fabrics? Most people attempt to<br />

identify fabric by feel. With today’s textile manufacturing<br />

technology, you can be completely fooled by this method.<br />

The bottom line is that identification by touch only is extremely<br />

unreliable. A more analytical approach is required<br />

to accurately differentiate one fabric from another<br />

What are the other identifying factors? As we move<br />

through this section, we will be looking at many fabrics<br />

that have the same fabric structure but different names.<br />

First, we must define the criteria <strong>for</strong> identifying fabrics so<br />

that recognition becomes possible. Then we will apply the<br />

basic criteria to each fabric in order to identify it.<br />

Criteria <strong>for</strong> Fabric Identification<br />

The names of fabrics are often tied to their characteristics<br />

and there<strong>for</strong>e can be helpful in determining a fabric’s<br />

identity.<br />

• <strong>Fabrics</strong> can be named <strong>for</strong> their inherent structure.<br />

Herringbone is always a reversing twill; the structure<br />

relates to the fabric’s method of construction and is<br />

created by a specific interlacing pattern. (Interlacings<br />

are the organization of horizontal and vertical—warp<br />

and weft—yarns as they cross over and under one another.)<br />

• Fiber content is sometimes responsible <strong>for</strong> a fabric’s<br />

name, such as China silk or handkerchief linen. Linen<br />

is usually, but not always, made of flax, but China silk<br />

is always a plain weave made of silk.<br />

• <strong>Fabrics</strong> can be named <strong>for</strong> their origins, such as damask<br />

<strong>for</strong> Damascus; paisley <strong>for</strong> the city in Scotland, and<br />

gauze <strong>for</strong> Gaza.<br />

• <strong>Fabrics</strong> are often distinguished by their finishes. Flannelette<br />

is generally a simple plain-weave cotton fabric.<br />

With a napped finish it becomes flannelette and even<br />

per<strong>for</strong>ms differently. Without this finish, it would not<br />

be flannelette.<br />

• Method of coloration is often a factor in identification.<br />

Gingham, chambray, and madras are all plainweave<br />

cotton fabrics that are in the same weight<br />

category. The differences between them lie in the<br />

organization of their yarn-dyed colors. Madras uses<br />

several yarn-dyed colors in both directions, creating a<br />

plaid design. Chambray has a white weft and colored<br />

warp. Gingham uses alternating blocks of white and a<br />

color in both directions to <strong>for</strong>m a checked pattern.<br />

Young_06.indd 38 8/31/10 8:27:15 AM

• Yarn construction can determine fabric identity.<br />

Voile and batiste are basically the same fabric, with<br />

differently twisted yarns. Voile has hard-twisted yarns;<br />

batiste is much softer. The placement of spun and filament<br />

yarns can determine fabric name as well. Bengaline<br />

is often identified by a spun weft and filament<br />

warp.<br />

• Print can be a determining factor. Calico is a lightweight,<br />

plain-weave, cottonlike fabric with a small<br />

floral print. Although each of these factors is important,<br />

it is ultimately the print that gives this fabric its<br />

identity and distinguishes it from many other fabrics<br />

of like hand and structure.<br />

• Finally, weight is an important consideration. Often,<br />

fabrics with different identities share the same fiber,<br />

yarn, and fabric construction. Poplin and broadcloth<br />

are basically the same fabric; their distinguishing feature<br />

is simply weight. Broadcloth is a lighter-weight<br />

version of poplin.<br />

The last factor on this list, weight, is one of the most<br />

significant, defining criteria of a fabric. Fabric is often<br />

bought and sold by weight.<br />

Consider the case of denim. This is an extremely<br />

common fabric that everyone knows, but not all denim is<br />

the same. Denim is described by weight, often expressed<br />

as ounces per square yard (oz./sq. yd.). Denim can range<br />

from a very thin, light-weight 4 to 5 ounces per square<br />

yard up to the aptly named bull denim, which can weigh<br />

as much as 18 ounces per square yard. Different weights<br />

of fabrics have different uses. Top weight generally means<br />

that a fabric is an appropriate weight <strong>for</strong> the top half of the<br />

body—a blouse or shirt. Bottom weight is appropriate <strong>for</strong><br />

the bottom half of the body—pants, slacks, or even suiting<br />

materials. Note in Table 6.1, which shows appropriate uses<br />

table 6.1 Basic Weight Categories<br />

Category oz./sq. yd. Appropriate End Uses<br />

Extremely Light Weight (i.e., lingerie) 0–1 oz. or<br />

< 1 oz.<br />

P l a i n w e a v e S<br />

39<br />

<strong>for</strong> fabrics of different weights, that the medium category<br />

straddles both top and bottom weights. This is a fabric<br />

that is generally considered heavy <strong>for</strong> a blouse, light <strong>for</strong><br />

a pant.<br />

Organization of <strong>Fabrics</strong> in This Text<br />

<strong>Fabrics</strong> in this text are logically organized into groups by<br />

their similarities, beginning with the simplest weave structure,<br />

plain weave. Within each chapter, the fabric organization<br />

will progress from the lightest weight up through<br />

the heavier weight versions of each structure.<br />

<strong>Fabrics</strong> have been around <strong>for</strong> a long time. Because<br />

manufactured fibers had not yet been created, all fabrics<br />

were originally invented with one of the big-four fibers:<br />

wool, linen, silk, and cotton. This text will often refer to<br />

fabrics as cottonlike or from the cotton family, which relates<br />

to their first incarnations and to their hand. Today, a cottonlike<br />

fabric might be made entirely of polyester. (This<br />

would be an example of polyester imitating cotton, as it<br />

often does.)<br />

The elements of a textile, which are identified with<br />

each fabric, are fiber content, yarn construction, fabric<br />

name, count, coloration method, finishes, and weight. In<br />

terms of yarn construction, one can assume that all yarns<br />

are single unless identified as plied. In the case of filament,<br />

assume multifilament, since this is most often the case in<br />

fabrics. This text also acknowledges that fabrics receive<br />

about a dozen finishes be<strong>for</strong>e they reach the consumer.<br />

Most of these finishes are general, such as washing, ironing,<br />

or bleaching. These will be assumed and not listed.<br />

Only aesthetic (visible) finishes will be listed.<br />

As a final note, fiber and fabrics are not inextricably<br />

linked. Batiste is a fabric that can be made of cotton, polyester,<br />

silk, or even rayon. Think of fiber and fabric as first<br />

Chiffon dresses/blouses, sheers<br />

Light Weight (i.e., top weight) 1–4 oz./sq. yd. Blouses, light summer dresses<br />

Medium Weight* (i.e., top weight, bottom weight) 4–7 oz./sq. yd. Heavier top weight and lighter bottom weight slacks and<br />

suitings<br />

Medium to Heavy Weight (i.e., bottom weight) 7–9 oz./sq. yd. Bottom weight slacks and suitings, lightweight summer<br />

jackets<br />

Heavy Weight (i.e., jacket or blanket weight) > 9 oz. Blankets, heavier coats<br />

* Medium weight comprises both top and bottom weights. This is a fabric that is generally considered heavy <strong>for</strong> a blouse and light <strong>for</strong> a pant.<br />

Young_06.indd 39 8/31/10 8:27:15 AM

Name: Date:<br />

Purpose: To determine why certain fibers are used <strong>for</strong> specific consumer end products, based on<br />

evaluation of their properties.<br />

Procedure<br />

1. Research the Internet or retail catalogs to find<br />

five textile-based consumer apparel adver-<br />

tisements that provide the generic fiber con-<br />

tent in the ad.<br />

• The five ads should include:<br />

- one natural protein fiber ad<br />

- one natural cellulose fiber ad<br />

- one man-made cellulose fiber ad<br />

- two different synthetic fiber ads<br />

• Avoid blends. Find ads with single-fiber fab-<br />

rics.<br />

2. Property names: Identify the three most posi-<br />

tive properties <strong>for</strong> the fiber featured in each<br />

of the ads. Select properties that reflect the<br />

best qualities of the fiber.<br />

3. Definitions of properties: Define each of the<br />

three properties you have identified <strong>for</strong> each<br />

advertisement to validate consumer end use.<br />

For each property, provide a correct, specific<br />

description stated in your own words. Finally,<br />

explain why the fiber is relevant to the prod-<br />

uct’s end use.<br />

4. Prepare a presentation on your findings in-<br />

cluding the following:<br />

• Create a title page with the title of the project,<br />

your name, your instructor’s name, the course<br />

number, the class day and time, and the date.<br />

activity 6.1 Research Project: Generic fiber Project<br />

• Place each ad securely and cleanly on a separate<br />

8 1/2×11-inch page. Alternatively, cut and paste<br />

internet ads onto the page. The ads should in-<br />

clude the text from the ad describing the product<br />

and the fiber content. Highlight the text that de-<br />

scribes the fiber content.<br />

• Follow the ad with your typed, double-spaced<br />

content, which should appear on the same<br />

page as the ad.<br />

• Attach all sheets in the packet with a staple.<br />

Tips<br />

• Choose properties relevant to the consumer!<br />

(For example, avoid the dimensional stability<br />

of a wedding gown or a polyester bikini that<br />

will keep you warm!)<br />

• Avoid properties that are average. Sell this<br />

garment with the best possible properties!<br />

• Write about fiber, not fabric.<br />

• Avoid trade names; this is a generic fiber as-<br />

signment.<br />

• Use <strong>for</strong>mal properties: cheap and washable<br />

are not properties.<br />

• Each of the five ads must feature a different<br />

fiber, and each fiber must be intended <strong>for</strong> a<br />

different consumer end use.<br />

Young_06.indd 41 8/31/10 8:27:17 AM

5<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong><br />

Fiber content: Cotton<br />

Fabric name: Lawn<br />

Yarn construction: Spun<br />

Count: 108×88<br />

Coloration: Print<br />

Weight: 1.7 oz./sq. yd.<br />

Uses: Blouses and summer wear<br />

Cellulose Fibers<br />

Cellulose Fibers<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong> 5 <strong>Swatch</strong> 6<br />

6<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong><br />

Fiber content: Organically color-grown<br />

cotton<br />

Fabric name: Poplin<br />

Yarn construction:<br />

Count: 64×35<br />

Coloration: Color grown, natural, undyed<br />

Weight: 6 oz./sq. yd.<br />

Uses: Jacket, blouses, bottom weight, and<br />

decorative uses<br />

© 2011 <strong>Fairchild</strong> <strong>Books</strong>, a division of Condé Nast Publications, Inc. Chapter 2: Fiber Classifications: Natural Fibers<br />

Young_<strong>Swatch</strong>Boards_Final.indd 113 8/31/10 9:27:05 AM

7<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong><br />

Cellulose Fibers Cellulose Fibers Cellulose Fibers<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong> 7 <strong>Swatch</strong> 8 <strong>Swatch</strong> 9<br />

Fiber content: Flax<br />

Fabric name: Butcher linen<br />

Yarn construction: Spun<br />

Count:<br />

Coloration: Natural color<br />

Weight: 7.1 oz./sq. yd.<br />

Uses: Suitings, blouses, and skirts<br />

8<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong><br />

Fiber content: Ramie<br />

Fabric name: Plain-weave “linen”<br />

Yarn construction: Spun<br />

Count: 66×54<br />

Coloration: Piece dyed<br />

Finishes: Beetled<br />

Weight: 5.5 oz./sq. yd.<br />

Uses: Suitings, blouses, and dresses<br />

© 2011 <strong>Fairchild</strong> <strong>Books</strong>, a division of Condé Nast Publications, Inc. Chapter 2: Fiber Classifications: Natural Fibers<br />

9<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong><br />

Fiber content: Hemp<br />

Fabric name: Jersey<br />

Yarn construction: Spun<br />

Count:<br />

Coloration: Bleached<br />

Weight: 7.4 oz./sq. yd.<br />

Uses: Tops and T-shirts<br />

Young_<strong>Swatch</strong>Boards_Final.indd 114 8/31/10 9:27:05 AM

160<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong><br />

Fabric name: Pleather<br />

Fiber content: Vinyl/polyester<br />

Yarn construction: None on face<br />

Count: None<br />

Coloration: Print<br />

Finishes: Embossed<br />

Fabric Combinations<br />

Weight: 13.08 oz./sq. yd.<br />

Uses: Any leather type applications<br />

Characteristics<br />

Laminated, or bonded, fabrics are made<br />

of two to three layers of fabric that are<br />

joined through any number of processes.<br />

Pleather is an embossed film that has<br />

been printed and laminated to a jersey (in<br />

this example). The resultant fabric is an<br />

imitation leather.<br />

161<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong><br />

Fabric name: Quilt<br />

Fiber content: Polyester<br />

Yarn construction: Varies<br />

Count: Varies<br />

Fabric Combinations<br />

<strong>Swatch</strong> 160 <strong>Swatch</strong> 161<br />

Coloration: Piece dyed<br />

Weight: 8.84 oz./sq. yd.<br />

Uses: Jackets, bedding<br />

Characteristics<br />

A quilted fabric is three layers of fabric<br />

that are sewn together with a decorative<br />

stitch. Traditionally, the face is woven, the<br />

backing could be anything, commonly a<br />

muslin and the middle layer is a nonwoven<br />

batting. This fabric has a 1 × 1 rib knit<br />

backing.<br />

Similarities<br />

These fabrics are made by combining layers of fabrics, which changes the weight, hand, and<br />

per<strong>for</strong>mance of the original fabric. Individually, the fabrics may be woven or knit, but the fabric<br />

has a new value by virtue of being combined and layered.<br />

© 2011 <strong>Fairchild</strong> <strong>Books</strong>, a division of Condé Nast Publications, Inc. Chapter 15: Minor Fabrications<br />

Young_<strong>Swatch</strong>Boards_Final.indd 182 8/31/10 9:27:21 AM