Edentata 7 - Anteater, Sloth & Armadillo Specialist Group

Edentata 7 - Anteater, Sloth & Armadillo Specialist Group

Edentata 7 - Anteater, Sloth & Armadillo Specialist Group

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Edentata</strong><br />

The Newsletter of the IUCN Edentate <strong>Specialist</strong> <strong>Group</strong> • May 2006 • Number 7<br />

ISSN 1413-4411<br />

Editors: Gustavo A. B. da Fonseca, Anthony B. Rylands and John M. Aguiar<br />

Assistant Editor: Mariella Superina<br />

ESG Chair: Gustavo A. B. da Fonseca<br />

ESG Deputy Chair: Mariella Superina

<strong>Edentata</strong><br />

The Newsletter of the IUCN/SSC Edentate <strong>Specialist</strong> <strong>Group</strong><br />

Center for Applied Biodiversity Science<br />

Conservation International<br />

1919 M St. NW, Suite 600, Washington, DC 20036, USA<br />

ISSN 1413-4411<br />

DOI: 10.1896/ci.cabs.2006.edentata.7<br />

Editors<br />

Gustavo A. B. da Fonseca, Center for Applied Biodiversity Science, Conservation International, Washington, DC<br />

Anthony B. Rylands, Center for Applied Biodiversity Science, Conservation International, Washington, DC<br />

John M. Aguiar, Center for Applied Biodiversity Science, Conservation International, Washington, DC<br />

Assistant Editor<br />

Mariella Superina, University of New Orleans, Department of Biological Sciences, New Orleans, LA<br />

Edentate <strong>Specialist</strong> <strong>Group</strong> Chairman<br />

Gustavo A. B. da Fonseca<br />

Edentate <strong>Specialist</strong> <strong>Group</strong> Deputy Chair<br />

Mariella Superina<br />

Layout<br />

Kim Meek, Center for Applied Biodiversity Science, Conservation International, Washington, DC<br />

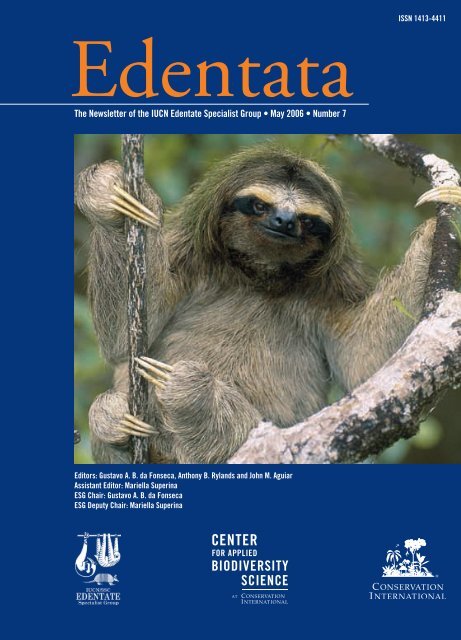

Front Cover Photo<br />

A pygmy sloth (Bradypus pygmaeus) in mangrove forest on Isla Escudo de Veraguas, Panama. Endemic to this<br />

single Caribbean island, pygmy sloths are hunted by local fishermen, and are now considered to be Critically<br />

Endangered. Photo © Bill Hatcher Photography.<br />

Editorial Assistance<br />

Liliana Cortés-Ortiz, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA<br />

Please direct all submissions and other editorial correspondence to John M. Aguiar, Center for Applied<br />

Biodiversity Science, Conservation International, 1919 M St. NW, Suite 600, Washington, DC 20036, USA,<br />

Tel. (202) 912-1000, Fax: (202) 912-0772, e-mail: .<br />

IUCN/SSC Edentate <strong>Specialist</strong> <strong>Group</strong> logo courtesy of Stephen D. Nash, 2004.<br />

This issue of <strong>Edentata</strong> was kindly sponsored by the Center for Applied Biodiversity Science, Conservation<br />

International, 1919 M St. NW, Suite 600, Washington, DC 20036, USA.

ARTICLES<br />

Situación de Los Edentados en Uruguay<br />

Alejandro Fallabrino<br />

Elena Castiñeira<br />

En el Uruguay hay reportados seis especies de edentados:<br />

mulita (Dasypus hybridus), tatú (Dasypus novemcinctus<br />

novemcinctus), tatú de rabo molle (Cabassous<br />

tatouay), peludo (Euphractus sexcinctus flavimanus),<br />

tamanduá (Tamandua tetradactyla chapadensis) y el<br />

oso hormiguero (Myrmecophaga tridactyla tridactyla)<br />

(González, 2001). Las especies de la Familia<br />

Dasypodidae son bastante comunes, exceptuando el<br />

C. tatouay del cual solo hay registros en los departamentos<br />

del noreste del país que limitan con Brasil,<br />

siendo esta zona el límite sur de su distribución (Tabla<br />

1, Fig. 1). El D. hybridus, D. novemcinctus y el E. sexcinctus<br />

se encuentran en todo el país, principalmente<br />

en ambientes de monte y de praderas.<br />

De la Familia Myrmecophagidae existe un solo registro<br />

de M. tridactyla asociado a yacimientos arqueológicos<br />

(González et al., 2001). El tamanduá fue registrado<br />

por primera vez en Uruguay a fines de la década de<br />

los ‘90 cuando fue encontrado un ejemplar vivo en el<br />

departamento de Cerro Largo. A partir de ese hecho<br />

se han registrado más ejemplares en los departamentos<br />

vecinos de Rivera y Tacuarembó (Berrini, 1998).<br />

Cabe destacar que esta zona es el límite sur de distribución<br />

de la especie para Sudamérica (Fonseca y Aguiar,<br />

2004).<br />

Investigación<br />

En Uruguay son casi nulos los estudios de edentados.<br />

El primer reporte sobre el tatú de rabo molle<br />

FIGURA 1. Registros del Cabassous tatouay y Tamandua t.<br />

chapadensis.<br />

(Ximenez y Achaval, 1966) y estudios sobre la cavidad<br />

de la mulita (González et al., 2001) son de las pocas<br />

publicaciones que existen. Los registros esencialmente<br />

se han realizado en salidas de colecta e inventarios<br />

que han realizado la Facultad de Ciencias y el Museo<br />

Nacional de Historia Natural, o por algún particular<br />

que ha donado especímenes.<br />

Conservación<br />

El creciente desarrollo agropecuario y forestal, junto<br />

a la disminución del monte indígena en las últimas<br />

décadas, trajo una importante pérdida del hábitat para<br />

todas las especies de edentados en nuestro territorio.<br />

En Uruguay existen varios tamanduás y osos hormigueros<br />

provenientes de Argentina y Brasil que se<br />

encuentran en cautiverio en zoológicos y reservas de<br />

fauna. Los escasos registros de tamanduás en vida<br />

TABLA 1. Situación de los edentados en Uruguay.<br />

Nombre común Distribución Status nacional Problemáticas<br />

Mulita Todo el país Susceptible<br />

Caza para alimentación y fabricación<br />

de artesanías<br />

Tatú Todo el país Susceptible<br />

Caza para alimentación y fabricación<br />

de artesanías<br />

Tatú de rabo molle<br />

Lavalleja, Cerro Largo y posibles registros<br />

para Rivera y Treinta y Tres conocido<br />

Amenazado e insuficientemente<br />

Pérdida de hábitat<br />

Peludo Todo el país Susceptible<br />

Caza para alimentación y fabricación<br />

de artesanías<br />

Oso hormiguero Rocha–un solo registro arqueológico Extinguido —<br />

Tamanduá<br />

Rivera, Cerro Largo y Tacuarembó<br />

Amenazado e insuficientemente<br />

conocido<br />

Pérdida de hábitat, caza deportiva<br />

1

A<br />

B<br />

está totalmente prohibida la exportación e importación<br />

de cualquier producto o subproducto de<br />

estas especies.<br />

A pesar de poseer legislación que las protege, la misma<br />

no es muy efectiva debido a que no existe un control<br />

permanente sobre la presión de caza y el comercio de<br />

las mismas.<br />

FIGURA 2. (A) Cuchillo artesanal con mango de mulita. (B) Venta de<br />

caparazón de tatú en feria de la capital, Montevideo. (A. Fallabrino.)<br />

silvestre son principalmente de reportes de animales<br />

muertos por personas que ante lo desconocido prefieren<br />

cazarlos.<br />

En Uruguay las especies de la Familia Dasypodidae<br />

han sido utilizadas para consumo humano y artesanal<br />

desde la época prehispánica. Pero es en el siglo<br />

XX que se comienza a ejercer una presión sobre<br />

estas especies debido al crecimiento demográfico en<br />

zonas rurales.<br />

Existe un tradicional consumo de carne de armadillos,<br />

siendo denominada por algunos como un manjar. Si<br />

bien en algunas zonas rurales la gente más vieja realiza<br />

un consumo racional, existe una depredación por<br />

parte de personas de las grandes ciudades. Esto se<br />

puede observar en las salidas de cacería que organizan<br />

los citadinos, donde llegan a capturar decenas de individuos.<br />

La venta ilegal de carne se da principalmente<br />

en el medio rural, en comercios establecidos y en casas<br />

de particulares. También la carne es enviada a familiares<br />

y amigos a través de los buses de larga distancia,<br />

sin que exista ningún control sobre el mismo.<br />

El caparazón y la cola son utilizados para la creación<br />

de artesanías (adornos, mangos, etc.) que se venden<br />

con total impunidad en ferias y comercios del país<br />

(Fig. 2). Otra problemática es el atropellamiento en<br />

rutas nacionales donde una gran cantidad de mulitas<br />

y tatúes aparecen muertos.<br />

Todas las especies de edentados se encuentran en<br />

la Nómina Oficial de Especies de la Fauna Silvestre<br />

(Decreto N° 514/001) y están protegidas a nivel<br />

nacional por la Ley de Fauna (9.481) y por el decreto<br />

que la reglamenta (164/996), el cual establece la prohibición<br />

de caza, transporte, tenencia, comercialización<br />

e industrialización de las especies de la fauna<br />

silvestre. A nivel internacional Uruguay es parte de la<br />

Convención Internacional para el Tráfico de Especies<br />

Amenazadas (CITES) desde el año 1975 por lo que<br />

Status y futuro<br />

Si bien González (2001) y Achaval et al. (2004) designaron<br />

un status nacional a los edentados en Uruguay<br />

(Tabla 1), debido a los pocos estudios, es importante<br />

también tomar como referencia el status regional<br />

(Argentina y Brasil) y de la UICN (Unión Internacional<br />

para la Conservación de la Naturaleza) hasta que<br />

no exista una investigación profunda sobre la situación<br />

actual de estas especies.<br />

Es necesario generar estudios a largo plazo, constantes<br />

y con fondos que permitan saber más sobre la distribución,<br />

biología y ecología de los edentados en<br />

Uruguay. Todo esto acompañado de actividades de<br />

conservación y educación localizadas principalmente<br />

en el medio rural, fomentando la valoración y protección<br />

de los mismos. A su vez con los tamanduás<br />

y osos hormigueros en cautiverio sería interesante<br />

poder generar intercambios y estudios en conjunto<br />

con Argentina y Brasil y así poder apoyar a los proyectos<br />

de reintroducción.<br />

Alejandro Fallabrino, CID/Antitrafico Neotropical,<br />

D. Murillo 6334, Montevideo, Uruguay, correo<br />

electrónico: y Elena Castiñeira,<br />

CID/AN y Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad<br />

de la República Oriental del Uruguay, Montevideo,<br />

Uruguay, correo electrónico: .<br />

Referencias<br />

Achaval, F., Clara, M. y Olmos, A. 2004. Mamíferos<br />

de la República Oriental del Uruguay. 1a. edición.<br />

Imprimex, Montevideo, Uruguay.<br />

Berrini, R. 1998. Cuenca Superior del Arroyo del<br />

Lunarejo. Ministerio de Vivienda, Ordenamiento<br />

Territorial y Medio Ambiente & Sociedad Zoológica<br />

del Uruguay. Montevideo.<br />

Fonseca, G. A. B. da y Aguiar, J. M. 2004. The 2004<br />

Edentate Species Assessment Workshop. <strong>Edentata</strong><br />

(6): 1–26.<br />

González, E. M. 2001. Guía de Campo de los Mamíferos<br />

del Uruguay. Introducción al Estudio de los<br />

Mamíferos. Vida Silvestre, Montevideo.<br />

González, E. M., Soutullo, A. y Altuna, C. 2001. The<br />

burrow of Dasypus hybridus (Desmarest, 1804)<br />

2<br />

<strong>Edentata</strong> no. 7 • May 2006

(Cingulata: Dasypodidae). Acta Theriologica<br />

46(1): 53–59.<br />

Ximenez, A. y Achaval, F. 1966. Sobre la presencia<br />

en el Uruguay del tatú de rabo molle, Cabassous<br />

tatouay (Desmarest) (<strong>Edentata</strong>, Dasypodidae).<br />

Com. Zool. Mus. Hist. Nat. Montevideo 9(109):<br />

1–5.<br />

Edentates of the Saracá-Taquera National Forest,<br />

Pará, Brazil<br />

Leonardo de Carvalho Oliveira<br />

Sylvia Miscow Mendel, Diogo Loretto<br />

José de Sousa e Silva Júnior<br />

Geraldo Wilson Fernandes<br />

Introduction<br />

The order Xenarthra contains 31 living species<br />

distributed in 13 genera, all but one of which are<br />

restricted to the Neotropics (Wetzel, 1982; Fonseca<br />

and Aguiar, 2004). Nineteen of these species, distributed<br />

in ten genera and four families, can be found<br />

in Brazil (Fonseca et al., 1996). This order embodies<br />

a substantial amount of the evolutionary history of<br />

mammals (Fonseca, 2001) and is potentially a basal<br />

offshoot of the earliest placental mammals (Murphy<br />

et al., 2001). Despite their ecological importance<br />

and the need to highlight them in conservation<br />

programs, xenarthrans are virtually unstudied when<br />

compared with other, better-known mammals (Fonseca,<br />

2001).<br />

At least 13 species of xenarthrans are found in the<br />

rainforests of Amazonia, four of which are endemic<br />

(Fonseca et al., 1996); another two are on the Brazilian<br />

Red List of threatened species (Fonseca and<br />

Chiarello, 2003). Although the Xenarthra include<br />

few species compared with other orders of Brazilian<br />

mammals, only a handful of field studies have focused<br />

on them, and their geographic distributions are still<br />

poorly known. Here we present data on the occurrence<br />

of xenarthrans in the Saracá-Taquera National<br />

Forest (STNF) in northwestern Pará, Brazil.<br />

Field Site and Methods<br />

The Saracá-Taquera National Forest (429,600 ha) is a<br />

bauxite-rich area immediately south of the village of<br />

Porto Trombetas (01°40′S, 56°00′W), in the municipality<br />

of Oriximiná in western Pará. Our study site<br />

in the STNF is about 100 km west of the confluence<br />

of the Rios Trombetas and Amazonas. The bauxite is<br />

mined by the Rio do Norte Mining Company (Mineração<br />

Rio do Norte — MRN). The deposits are associated<br />

with a series of Tertiary boundaries, occurring<br />

in small plateaus at altitudes between 150 –200 m.<br />

Mining bauxite on these plateaus involves the wholesale<br />

removal of the rainforest along with the first<br />

4–15 m of soil. Heavy machinery works around the<br />

clock to extract the ore, which is the raw material for<br />

the production of aluminum. After an area has been<br />

mined out, the pits are filled with a mixture of soil<br />

and vegetative debris, and the area is replanted with<br />

native seedlings by the mining company.<br />

Our fieldwork for this study focused on three regions:<br />

the Almeidas plateau, which has been undergoing<br />

stepwise deforestation since 2002; in areas on the<br />

Saracá plateau, which was mined out and reforested<br />

during the 1980s and 1990s; and on sightings and<br />

road kills along a 30-km stretch of road between<br />

Porto de Trombetas and the Almeidas plateau (Fig.<br />

1). From April 2002 to December 2004, a small team<br />

of three carried out ten field trips of 15 days each.<br />

On each field trip, the team was composed of two<br />

researchers (L. C. Oliveira and either S. M. Mendel or<br />

D. M. Loretto) plus a field assistant. Edentates were<br />

recorded whenever they were seen on trails in both<br />

mature forest and reforested areas.<br />

Additional records on the occurrence of edentates<br />

in the region were gathered from publications<br />

(Wetzel, 1982, 1985a, 1985b; Emmons and Feer,<br />

1997; Eisenberg and Redford, 1999; Silva Júnior<br />

and Nunes, 2001; Silva Júnior et al., 2001) as<br />

well as two technical reports: the Saracá-Taquera<br />

National Forest Management Plan (STCP, 2001)<br />

and an environmental impact study (Brandt Meio<br />

Ambiente, 2001), as well as from specimens in the<br />

Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi (MPEG), Belém.<br />

During our fieldwork in STNF we found 11 dead<br />

animals, which we compared directly with museum<br />

specimens at MPEG. We deposited tissue samples<br />

from the animals at the PUCMinas Natural History<br />

Museum, and also took reference photographs of<br />

live animals in the field.<br />

We interviewed four technicians from the Brazilian<br />

Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural<br />

Resources (IBAMA) who were working in the region,<br />

and also ten of our local field assistants. We presented<br />

each interviewee with the illustrations of the Xenarthra<br />

from Emmons and Feer (1997), and asked them<br />

to identify those which they had seen in the region.<br />

For each sighting they reported, we noted the species,<br />

the type of record, and the location and estimated<br />

date of the sighting. We also asked to see any remains,<br />

such as the skulls and carapaces of animals which were<br />

either hunted or found dead.<br />

3

FIGURE 1. Map of the Saracá-Taquera National Forest with the study areas represented.<br />

Results<br />

Based on information compiled from our fieldwork,<br />

the scientific literature, technical reports, museum<br />

collections and interviews, we found evidence for<br />

up to 13 xenarthran species occurring in the STNF<br />

(Table 1). The geographic distribution of ten of<br />

them suggests their occurrence in the study area. The<br />

other three were mentioned only in the two technical<br />

reports; they have yet to be confirmed, and may<br />

be erroneous.<br />

Fieldwork<br />

We found six xenarthran species in our field surveys,<br />

three of them in reforested areas (Table 1). We recorded<br />

three of the four known species of anteaters in the study<br />

area. Three giant anteaters (Myrmecophaga tridactyla)<br />

were seen in the reforested areas, twice in plots reforested<br />

in the 1980s and once in a plot from the 1990s.<br />

The southern tamandua (Tamandua tetradactyla) was<br />

seen on six occasions, four of which were in the remaining<br />

forest of the Almeidas plateau. We found a fifth<br />

individual dead in the 1990s reforested plot, showing<br />

unmistakable signs of predation — broken bones, bite<br />

marks on the head, and large parts of the body missing.<br />

The sixth was found dead on the road between Porto<br />

de Trombetas and the Almeidas plateau, probably killed<br />

by a vehicle. We also found a pygmy anteater (Cyclopes<br />

didactylus) killed on the same road.<br />

There are two species of sloth in the STNF: the<br />

pale-throated three-toed sloth (Bradypus tridactylus:<br />

Bradypodidae) and the two-toed sloth (Choloepus<br />

didactylus: Megalonychidae). A three-toed<br />

sloth was found dead on the road, and an IBAMA<br />

technician observed another crossing the road at<br />

Porto de Trombetas. Choloepus didactylus was the<br />

most frequently sighted of the xenarthrans during<br />

our field study, with a total of ten records for this<br />

species — six of which were dead specimens found<br />

on the road.<br />

We recorded just one species of armadillo, the<br />

common long-nosed armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus).<br />

We saw one in the Almeidas forest, and<br />

a second in the 1980s reforested zone at Saracá;<br />

a third was found dead on the road to Porto<br />

de Trombetas.<br />

Museum collections<br />

There are specimens of two xenarthran species from<br />

the STNF in the mammal collection of the Museu<br />

Paraense Emílio Goeldi: two of Bradypus variegatus<br />

(Faro and headwaters of the Rio Paru do Oeste), and<br />

one of the greater long-nosed armadillo, Dasypus<br />

kappleri, collected from the Rio Saracazinho, Porto<br />

Trombetas (Table 1).<br />

4<br />

<strong>Edentata</strong> no. 7 • May 2006

Interviews and published literature<br />

The presence of the giant armadillo (Priodontes<br />

maximus) was inferred by its burrows (recorded by<br />

an IBAMA technician, Antônio de Almeida Correia)<br />

and it was also listed during inventories for<br />

an environmental impact statement (Brandt Meio<br />

Ambiente, 2001) and for the preparation of a management<br />

plan for the national forest (STCP, 2001).<br />

The Brazilian lesser long-nosed armadillo (Dasypus<br />

septemcinctus) may also be present, as one of the technicians<br />

we interviewed described two different species<br />

of armadillos, one with nine bands in the carapace<br />

and the other with seven. The technician was unable<br />

to identify the exact species from the illustrations we<br />

provided, however, and this record is provisional. The<br />

southern naked-tail armadillo (Cabassous unicinctus),<br />

the Brazilian three-banded armadillo (Tolypeutes<br />

tricinctus) and the yellow armadillo (Euphractus sexcinctus)<br />

were only recorded in some publications and<br />

technical reports (Table 1).<br />

Discussion<br />

Although our study registered a potential total of 13<br />

xenarthran species in the Saracá-Taquera National<br />

Forest, not all have been verified. The Brazilian threebanded<br />

armadillo (Tolypeutes tricinctus), although<br />

listed in a technical report (STCP, 2001) is unlikely to<br />

occur in the study area. It has never been recorded in<br />

Amazonia, and occurs mainly in the Cerrado biome<br />

(Wetzel, 1982, 1985a; Fonseca et al., 1996; Eisenberg<br />

and Redford, 1999).<br />

The presence of the yellow armadillo (Euphractus sexcinctus)<br />

also remains to be confirmed. According to<br />

Wetzel (1985a), this species occurs in northeastern,<br />

middle-western, southeastern, and southern Brazil,<br />

but Silva Júnior and Nunes (2001) and Silva Júnior<br />

et al. (2001) have found it in the eastern Amazon,<br />

and proposed that its disjunct range is an artifact of<br />

sampling. Our records for this species are based only<br />

on interviews and technical reports.<br />

TABLE 1. Edentate fauna reported from the Saracá-Taquera National Forest, Pará, Brazil, from scientific collections, published reports and<br />

fieldwork. The number of individuals observed is given in parentheses.<br />

Order <strong>Edentata</strong><br />

Museum Literature Fieldwork<br />

MPEG<br />

Technical<br />

reports<br />

Scientific<br />

papers<br />

Mature<br />

forest<br />

Reforested<br />

area<br />

Myrmecophagidae<br />

Myrmecophaga tridactyla 1, 2 1, 3, 4, 5 Obs. (3)<br />

Tamandua tetradactyla 1, 2 1, 3, 4, 5 Obs. (4) Obs. (1) Obs.(1)<br />

Cyclopes didactylus 1, 2 1, 3, 4, 5 Obs. (1)<br />

Bradypodidae<br />

Bradypus tridactylus 1, 3, 4, 5 Obs.(2)<br />

Bradypus variegatus* 304; 1743 1, 2 1, 3, 5<br />

Megalonychidae<br />

Choloepus didactylus 1, 2 1, 3, 4, 5 Obs. (4) Obs.(6)<br />

Dasypodidae<br />

Priodontes maximus 1, 2 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Int.<br />

Cabassous unicinctus 1, 2 1, 2, 3, 4, 5<br />

Tolypeutes tricinctus** 1<br />

Dasypus kappleri*** 12592 1, 2, 3, 4, 5<br />

Dasypus novemcinctus 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Obs (1) Obs. (1) Obs. (1)<br />

Dasypus septemcinctus****<br />

Int.<br />

Euphractus sexcinctus 1, 2<br />

Literature: 1 Wetzel, 1982; 2 Wetzel, 1985a; 3 Wetzel, 1985b; 4 Emmons and Feer, 1997; 5 Eisenberg and Redford, 1999.<br />

Technical reports: 1. STCP, 2001; 2. Brandt Meio Ambiente, 2001.<br />

* MPEG 304: Faro and MPEG 1743: Cabeceiras do Rio Paru de Oeste.<br />

** Improbable occurrence due to a geographic range restricted to other biomes.<br />

*** MPEG 12592: Rio Saracazinho, Porto Trombetas.<br />

**** Species recorded by interview and recorded in the Porto Trombetas Biological Reserve.<br />

Obs. = Direct observation of the species.<br />

Int. = Interview.<br />

Road<br />

5

Dasypus septemcinctus has yet to be confirmed for the<br />

STNF. It has a broad range, from the mouth of the<br />

Amazon to the Gran Chaco in Argentina (Wetzel,<br />

1985b), but none have been recorded from the central<br />

Amazon. As mentioned above, the presence of<br />

this species was suggested by one of the technicians<br />

we interviewed, and D. septemcinctus was listed in<br />

the management plan for the Rio Trombetas Biological<br />

Reserve, on the east side of the Rio Trombetas<br />

(Antônio de Almeida Correia, pers. comm.). Thus, we<br />

consider its occurrence possible for the STNF, but we<br />

have no concrete evidence of it having been seen or<br />

collected there.<br />

Three of the six species recorded in our fieldwork — two<br />

anteaters (Myrmecophaga tridactyla and Tamandua tetradactyla)<br />

and an armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) — were<br />

seen in reforested areas. These areas appear to be important<br />

for the xenarthran fauna at Porto de Trombetas;<br />

the giant anteater (M. tridactyla), for instance, was only<br />

recorded in these areas. This may have been due to<br />

easier visibility in those areas; but field studies will be<br />

necessary to determine how these reforested areas support<br />

the local xenarthran fauna, and how xenarthrans<br />

colonize reforested patches.<br />

The principal threats facing the xenarthran fauna of<br />

this region are hunting and roads. Road mortality has<br />

been considered one of the worst dangers to terrestrial<br />

fauna (Forman and Alexander, 1998), and all six<br />

of the species that we directly observed were found<br />

dead on the road. Xenarthrans are more vulnerable to<br />

highway traffic than most other mammals, as many<br />

of them have poor vision and are not equipped for a<br />

fast escape.<br />

Edentates are a favored source of meat throughout<br />

the Neotropics (Redford, 1992; Leeuwenberg, 1997;<br />

Cullen et al., 2000; Peres, 2000; Valsecchi, 2005),<br />

and many people in the STNF hunt wild game for<br />

food. Interviews with our field assistants indicated a<br />

strong preference for the armadillos, and our assistants<br />

showed us the carapaces of some recent kills.<br />

Despite the road casualties and local hunting, the<br />

Saracá-Taquera National Forest has a remarkable<br />

richness of xenarthran species. This gives it a special<br />

importance as a protected area, and makes it an excellent<br />

location to study the dynamics of mammal recolonization<br />

in regenerating tropical forest.<br />

Acknowledgements: We thank the Brazilian Institute<br />

of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources<br />

(IBAMA), Porto de Trombetas, Pará, for permission to<br />

work in the Saracá-Taquera National Forest; Antônio<br />

de Almeida Correia (IBAMA) for useful information;<br />

our colleagues from the Horto Florestal; Rio do<br />

Norte Mining Company (MRN) for logistical help,<br />

especially Alexandre Castilho; and Leonardo Viana<br />

and Lyn Buchheit for the English corrections. Rio do<br />

Norte Mining Company (MRN) and Planta Ltda.<br />

funded this study. The first author thanks CAPES/<br />

Fulbright for the fellowship in support of his doctoral<br />

studies at the University of Maryland.<br />

Leonardo de Carvalho Oliveira, Graduate Program<br />

in Biology, University of Maryland, College Park,<br />

MD 20742, USA, e-mail: ,<br />

Sylvia Miscow Mendel, Pós-Graduação em Ecologia<br />

Conservação e Manejo da Vida Silvestre, ICB,<br />

Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Av. Antônio<br />

Carlos, 6627, Pampulha, Belo Horizonte 30270-<br />

901, Minas Gerais, Brazil, e-mail: , Diogo Loretto, Programa de Pós-Graduação<br />

em Ecologia, Universidade Federal do Rio de<br />

Janeiro, CP 68020, Av. Brigadeiro Trompovsky s/n°,<br />

Ilha do Fundão, Rio de Janeiro 21941-590, Rio de<br />

Janeiro, Brazil, e-mail: , José de Sousa e Silva Júnior, Setor de Mastozoologia,<br />

Coordenação de Zoologia, Museu Paraense<br />

Emílio Goeldi, CP 399, Belém 66040-170,<br />

Pará, Brazil, e-mail: , and<br />

Geraldo Wilson Fernandes, Planta Ltda. and Ecologia<br />

Evolutiva de Herbívoros Tropicais / DBG, ICB,<br />

Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, CP 486, Belo<br />

Horizonte 30270-901, Minas Gerais, Brazil, e-mail:<br />

.<br />

References<br />

Brandt Meio Ambiente. 2001. Estudos de Impacto<br />

Ambiental Platô Almeidas. Unpublished report.<br />

Mineração Rio do Norte, Porto de Trombetas,<br />

Oriximiná, Pará.<br />

Cullen Jr., L., Bodmer, R. E. and Valladares-Pádua,<br />

C. 2000. Effects of hunting in habitat fragments<br />

of the Atlantic forests, Brazil. Biological Conservation<br />

95: 49–56.<br />

Eisenberg, J. F. and Redford, K. H. 1999. Mammals of<br />

the Neotropics, Volume 3: The Central Neotropics:<br />

Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Brazil. The University of<br />

Chicago Press, Chicago.<br />

Emmons, L. H. and Feer, F. 1997. Neotropical Rainforest<br />

Mammals: A Field Guide. Second edition.<br />

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago.<br />

Fonseca, G. A. B. da, Hermann, G., Leite, Y. L. R.,<br />

Mittermeier, R. A., Rylands, A. B. and Patton, J.<br />

L. 1996. Lista anotada dos mamíferos do Brasil.<br />

Occasional Papers in Conservation Biology 4: 1–38.<br />

Conservation International and Fundação Biodiversitas,<br />

Washington, DC.<br />

6<br />

<strong>Edentata</strong> no. 7 • May 2006

Fonseca, G. A. B. da. 2001. The conservation of xenarthra<br />

will be vital for the preservation of mammalian<br />

phylogenetic diversity. <strong>Edentata</strong> (4): 1.<br />

Fonseca, G. A. B. da and Aguiar, J. M. 2004. The<br />

2004 Edentate Species Assessment Workshop.<br />

<strong>Edentata</strong> (6): 1–26.<br />

Fonseca, G. A. B. da and Chiarello, A. G. 2003. Official<br />

list of Brazilian fauna threatened with extinction<br />

— 2002. <strong>Edentata</strong> (5): 56–59.<br />

Forman, R. T. T. and Alexander, L. E. 1998. Roads<br />

and their major ecological effects. Ann. Rev. Ecol.<br />

Syst. 29: 207–231.<br />

Leeuwenberg, F. 1997. <strong>Edentata</strong> as a food resource:<br />

Subsistence hunting by Xavante Indians, Brazil.<br />

<strong>Edentata</strong> (3): 4–5.<br />

Murphy, W. J., Eizirik, E., Johnson, W. E., Zhang, Y.<br />

P., Ryder, O. A. and O’Brien, S. J. 2001. Molecular<br />

phylogenetics and the origins of placental<br />

mammals. Nature 409: 614–618.<br />

Peres, C. A. 2000. Effects of subsistence hunting on<br />

vertebrate community structure in Amazonian<br />

forest. Conservation Biology 14(1): 240–253.<br />

Redford, K. H. 1992. The empty forest. BioScience 42:<br />

412–422.<br />

Silva Júnior, J. S. and Nunes, A. P. 2001. Disjunct<br />

geographical distribution of the yellow armadillo,<br />

Euphractus sexcinctus (Xenarthra: Dasypodidae).<br />

<strong>Edentata</strong> (4): 16–18.<br />

Silva Júnior, J. S., Fernandes, M. E. B. and Cerqueira,<br />

R. 2001. New records of the yellow armadillo,<br />

Euphractus sexcinctus (Xenarthra: Dasypodidae)<br />

in the state of Maranhão, Brazil. <strong>Edentata</strong> (4):<br />

18–23.<br />

STCP. 2001. Plano de Manejo da Floresta Nacional de<br />

Saracá-Taquera, Estado do Pará, Brasil. Unpublished<br />

report. STCP Engenharia, Consultoria e<br />

Gerenciamento, Curitiba, Paraná.<br />

Valsecchi, J. A. 2005. Diversidade de mamíferos não<br />

voadores e uso da fauna nas Reservas de Desenvolvimento<br />

Sustentável Mamirauá e Amanã, Amazonas,<br />

Brasil. Master’s thesis, Programa de Pós-Graduação<br />

em Zoologia, Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi and<br />

Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém.<br />

Wetzel, R. M. 1982. Systematics, distribution, ecology,<br />

and conservation of South American Edentates.<br />

In: Mammalian Biology in South America,<br />

M. A. Mares and H. H. Genoways (eds.), pp.<br />

345–375. Special Publication Series of the Pymatuning<br />

Laboratory of Ecology, University of Pittsburgh,<br />

Pittsburgh.<br />

Wetzel, R. M. 1985a. The identification and distribution<br />

of recent Xenarthra (= <strong>Edentata</strong>). In: The<br />

Evolution and Ecology of <strong>Armadillo</strong>s, <strong>Sloth</strong>s, and<br />

Vermilinguas, G. G. Montgomery (ed.), pp.5–21.<br />

Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC.<br />

Wetzel, R. M. 1985b. Taxonomy and distribution of<br />

armadillos, Dasypodidae. In: The Evolution and<br />

Ecology of <strong>Armadillo</strong>s, <strong>Sloth</strong>s, and Vermilinguas, G.<br />

G. Montgomery (ed.), pp.23–46. Smithsonian<br />

Institution Press, Washington, DC.<br />

A Southern Extension of the Geographic<br />

Distribution of the Two-Toed <strong>Sloth</strong>, Choloepus<br />

didactylus (Xenarthra, Megalonychidae)<br />

Cristiano Trapé Trinca<br />

Francesca Belem Lopes Palmeira<br />

José de Sousa e Silva Júnior<br />

The two species of two-toed sloths, Choloepus didactylus<br />

and C. hoffmanni, are the only extant representatives<br />

of the Megalonychidae (Adam, 1999),<br />

occurring in partial sympatry in the Andean regions<br />

and western Amazonia (Le Pont and Desjeux, 1992;<br />

Emmons and Feer, 1997; Adam, 1999; Eisenberg<br />

and Redford, 1999). Although their distributions<br />

are reasonably well-understood on a broad scale,<br />

the precise boundaries of their ranges are still unresolved.<br />

According to Wetzel and Ávila-Pires (1980),<br />

Wetzel (1985), Adam (1999) and Eisenberg and<br />

Redford (1999), C. didactylus occurs across all of<br />

northern Amazonia, from the eastern Andes to<br />

northeastern Surinam, reaching the northern coast<br />

of Brazil in the states of Amapá, Pará and Maranhão.<br />

The maps presented by Wetzel (1985), Emmons<br />

and Feer (1997) and Eisenberg and Redford (1999)<br />

all suggest that in Western Amazonia, this distribution<br />

extends southward to 10°S latitude. In central<br />

and eastern Amazonia, however, their maps show<br />

Choloepus didactylus as being restricted to a narrow<br />

belt along the southern edge of the Amazon River<br />

— although there is no ecological reason why the<br />

species might not occur further to the south. Wetzel<br />

and Ávila-Pires (1980) reported the only records for<br />

this region available at the time, referring to specimens<br />

from Santarém, Taperinha and Rio Barcarena<br />

in Pará, as well as Humberto de Campos in Maranhão.<br />

Specimens in the mammal collection of the<br />

Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi (MPEG) confirm<br />

this distribution, including those from the following<br />

localities in eastern Pará: Marituba (MPEG 22070),<br />

Paragominas (MPEG 30677), Fazenda Cauaxi,<br />

municipality of Paragominas (MPEG 26315,<br />

26316, 26317), and Rodovia Belém-Brasília, Km-<br />

75 (MPEG 2385, 2391, 2394). With the exception<br />

of the last three individuals, all these specimens were<br />

collected after 1980 and were thus not available to<br />

Wetzel and Ávila-Pires.<br />

7

Mascarenhas and Puorto (1988) reported C. didactylus<br />

from the middle-lower Rio Tocantins, south of<br />

the range indicated by other authors. The specimens<br />

which Mascarenhas and Puorto collected are now<br />

in the MPEG collection (Tucuruí, Base 5: MPEG<br />

12597; Jacundá: MPEG 11884), and these localities<br />

were included in the more recent range maps of Adam<br />

(1999) and Eisenberg and Redford (1999). Soon thereafter,<br />

Toledo et al. (1999) extended the distribution<br />

of C. didactylus to the region of Carajás in southern<br />

Pará, approximately 06°S, 50°W. Here we demonstrate<br />

that the eastern part of the distribution of this species<br />

extends further south than previously known.<br />

While one of us was conducting fieldwork in a settlement<br />

in northern Mato Grosso (Trinca, 2004), a<br />

local man found a skull of C. didactylus in the nearby<br />

plantation of Fazenda do Tenente, Japuranã district<br />

(10°03′56.6″S, 58°00′02.3″W), municipality of<br />

Nova Bandeirantes (Fig. 1). This area is located in<br />

the Juruena interfluve between the Rios Juruena and<br />

Teles Pires.<br />

The specimen, an adult skull without the mandible,<br />

is now in the MPEG mammal collection (MPEG<br />

36871). We identified the specimen based on the<br />

diagnostic characters provided by Wetzel (1985) and<br />

by direct comparison with specimens of Choloepus<br />

in the MPEG collection. The skull fits the description<br />

of C. didactylus, possessing a large anterior and<br />

small posterior inter-pterygoid space, large pterygoid<br />

expansions, absence of a posterior pair of foramina in<br />

the inter-pterygoid space, pterygoid sinuses broadly<br />

inflated and broad contact of maxilla with frontal<br />

bone, not interrupted by lacrimals.<br />

The original vegetation of the Juruena basin was<br />

mainly dense rainforest, interspersed with open<br />

rainforest and transitional areas (Dinerstein et al.,<br />

1995; Miranda and Amorim, 2000). Within the past<br />

30 years, these forests have been destroyed by the<br />

expansion of agriculture and pastures, and the<br />

increase in cattle-ranching and soybean farming may<br />

have extirpated C. didactylus from many areas in eastcentral<br />

Mato Grosso.<br />

FIGURE 1. Location of the southern records of C. didactylus, based on the distributions presented in Eisenberg (1989) and Eisenberg and<br />

Redford (1999): 1. Pará, Santarém (02°26′S, 54°42′W); 2. Pará, Taperinha (02°31′S, 54°17′W); 3. Pará, Rio Barcarena (01°30′S, 48°39′W);<br />

4. Pará, Marituba (01°22′S, 48°20′W); 5. Pará, Rodovia Belém-Brasília, Km 75 (01°19′S, 47°55′W); 6. Pará, Jacundá (04°39′S, 49°29′W);<br />

7. Pará, Fazenda Cauaxi (03°45′S, 48°10′W); 8. Pará, Paragominas (02°56′S, 47°31′W); 9. Pará, Tucuruí, Base 5 (approx. 03°42′S, 49°27′W);<br />

10. Pará, Carajás (06°05′S, 50°07′W); 11. Maranhão, Humberto de Campos (02°37′S, 43°27′W); 12. Mato Grosso, Fazenda do Tenente, Japuranã<br />

(10°03′S, 58°00′W).<br />

8<br />

<strong>Edentata</strong> no. 7 • May 2006

This new record suggests that the presumed absence<br />

of this species in south-central and eastern Amazonia<br />

may be an artifact of undersampling, which has<br />

long been an impediment to understanding the<br />

diversity and biogeography of Neotropical fauna<br />

(Vivo, 1996; Silva Júnior, 1998; Silva et al., 2001).<br />

Surveys covering this entire region would most likely<br />

indicate that C. didactylus has a wider geographic<br />

distribution within the forests of Amazonia than<br />

now understood.<br />

Acknowledgements: We are grateful to Mr. Marcos,<br />

who found the skull at Fazenda do Tenente and<br />

gave it to C. T. Trinca. We also thank Mr. Leonar<br />

Dallagnol, Mr. Antonio Geraldo Conjiu and Mr.<br />

Arley Brumati for their logistical support during<br />

the first author’s field research in the Juruena<br />

interfluve. Special thanks are due to Luís Cláudio<br />

Barbosa for drawing the map and to Marinus<br />

Hoogmoed, Teresa Cristina Sauer de Ávila-Pires,<br />

Ana Lima and John Aguiar for their reviews of<br />

the manuscript.<br />

Cristiano Trapé Trinca and Francesca Belem Lopes<br />

Palmeira, Faculdade de Ciências Biológicas, Centro<br />

de Ciências Médicas e Biológicas, Pontifícia Universidade<br />

Católica de São Paulo, Praça José Ermírio<br />

de Moraes, 290, Vergueiro, Sorocaba 18030-230,<br />

São Paulo, Brasil, and Departamento de Pesquisa,<br />

Reserva Brasil, Av. Dr. Silva Melo, 520, complemento<br />

606, Jardim Taquaral, São Paulo 04675-<br />

010, São Paulo, Brazil, e-mail: and , and José de Sousa e Silva Júnior, Coordenação<br />

de Zoologia, Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi<br />

(MPEG), Av. Perimetral, 1901/1907, Terra Firme,<br />

Belém 66077-530, PA, Brazil, e-mail: .<br />

References<br />

Adam, P. J. 1999. Choloepus didactylus. Mammalian<br />

Species 621: 1–8.<br />

Dinerstein, E., Olson, D. M., Graham, D. J., Webster,<br />

A. L., Primm, S. A., Bookbinder, M. P.<br />

and Ledec, G. 1995. A conservation assessment<br />

of the terrestrial ecorregions of Latin<br />

America and the Caribbean. The World Bank,<br />

Washington, DC.<br />

Eisenberg, J. F. 1989. Mammals of the Neotropics,<br />

Volume 1: The Northern Neotropics: Panama,<br />

Colombia, Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname, French<br />

Guiana. The University of Chicago Press,<br />

Chicago.<br />

Eisenberg, J. F. and Redford, K. 1999. Mammals of<br />

the Neotropics, Volume 3: The Central Neotropics:<br />

Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Brazil. The University of<br />

Chicago Press, Chicago.<br />

Emmons, L. H. and Feer, F. 1997. Neotropical<br />

Rainforest Mammals: A Field Guide. Second<br />

edition. The University of Chicago Press,<br />

Chicago.<br />

Le Pont, F. and Desjeux, P. 1992. Presence de Choloepus<br />

hoffmanni dans les Yungas de la Paz (Bolivie).<br />

Mammalia 56(3): 484–485.<br />

Mascarenhas, B. M. and Puorto, G. 1988. Nonvolant<br />

mammals rescued at the Tucuruí Dam in<br />

the Brazilian Amazon. Primate Conservation (9):<br />

91–93.<br />

Miranda, L. and Amorim, L. 2000. Mato Grosso:<br />

Atlas Geográfico. Ed. Entrelinhas, Cuiabá,<br />

Brazil.<br />

Silva Júnior, J. S. 1998. Problemas de amostragem no<br />

desenvolvimento da sistemática e biogeografia de<br />

primatas neotropicais. Neotropical Primates 6(1):<br />

21–22.<br />

Silva, M. N. F. da, Rylands, A. B. and Patton, J. L.<br />

2001. Biogeografia e conservação da mastofauna<br />

na floresta amazônica brasileira. In: Biodiversidade<br />

na Amazônia Brasileira: Avaliação e Ações<br />

Prioritárias para a Conservação, Uso Sustentável e<br />

Repartição de Benefícios, A. Vérissimo, A. Moreira,<br />

D. Sawyer, I. dos Santos, L. P. Pinto and J. P.<br />

R. Capobianco (eds.), pp. 110–131, 471–475.<br />

Instituto Socioambiental, Estação Liberdade,<br />

São Paulo.<br />

Toledo, P. M., Moraes-Santos, H. M. and Melo, C. C.<br />

S. 1999. Levantamento preliminar de mamíferos<br />

não-voadores da Serra dos Carajás: Grupos silvestres<br />

recentes e zooarqueológicos. Bol. Mus. Para.<br />

Emílio Goeldi Sér. Zool. 15(2): 141–157.<br />

Trinca, C. T. 2004. Caça em assentamento rural no<br />

sul da Floresta Amazônica. Master’s thesis, Museu<br />

Paraense Emílio Goeldi and Universidade Federal<br />

do Pará, Belém.<br />

Vivo, M. de. 1996. How many species of mammals<br />

are there in Brazil In: Biodiversity in Brazil:<br />

A First Approach, C. E. Bicudo and N. A. Menezes<br />

(eds.), pp.313–321. Proceedings of the Workshop<br />

“Methods for the Assessment of Biodiversity<br />

in Plants and Animals,” Campos do Jordão, São<br />

Paulo.<br />

Wetzel, R. M. and Ávila-Pires, F. D. 1980. Identification<br />

and distribution of recent sloths of Brazil.<br />

Rev. Brasil. Biol. 40: 831–836.<br />

Wetzel, R. M. 1985. The identification and distribution<br />

of recent Xenarthra (<strong>Edentata</strong>).<br />

In: The Evolution and Ecology of <strong>Armadillo</strong>s,<br />

<strong>Sloth</strong>s, and Vermilinguas, G. G. Montgomery<br />

(ed.), pp.5–21. Smithsonian Institution Press,<br />

Washington, DC.<br />

9

The Illegal Traffic in <strong>Sloth</strong>s and Threats to Their<br />

Survival in Colombia<br />

Sergio Moreno<br />

Tinka Plese<br />

Introduction<br />

The illegal trade in wildlife is driven by the high<br />

demand in national and international urban centers,<br />

making wildlife trafficking the third most lucrative<br />

criminal enterprise in Colombia, after the trade in<br />

weapons and drugs (CITES, 2005; Rodríguez and<br />

Echeverry, 2005). Together with the swift and pervasive<br />

destruction of tropical forests, this places many<br />

of the species reliant on these ecosystems in danger<br />

of extinction.<br />

This report is based on our observations at the UNAU<br />

Foundation sloth rehabilitation center during its first<br />

five years of operation, from 2000 to 2005, in the city<br />

of Medellín. Here we show how independent pressures<br />

have combined to threaten the survival of sloths<br />

in Colombia.<br />

<strong>Sloth</strong>s of Colombia<br />

Three species of sloths are known from Colombia<br />

(Wetzel, 1982). The brown-throated three-toed<br />

sloth, Bradypus variegatus (Schinz, 1825) inhabits<br />

both Pacific and Amazonian lowland rainforest and<br />

the Caribbean savanna dry forest (pers. obs.) (Fig.<br />

1). Hoffman’s two-toed sloth, Choloepus hoffmanni<br />

(Peters, 1859) is sympatric in the north with B. variegatus,<br />

sharing the Pacific rainforest and the Caribbean<br />

savanna dry forest, but is also found in Andean<br />

montane forest (pers. obs.). The southern two-toed<br />

sloth, Choloepus didactylus (Linnaeus, 1758) is<br />

sympatric in the south with B. variegatus, sharing<br />

the lowland Amazonian rainforest (Wetzel, 1982;<br />

Eisenberg, 1989; Emmons and Feer, 1999; Fonseca<br />

and Aguiar, 2004) but this species has been littlestudied<br />

in Colombia. The available habitat of these<br />

species is limited primarily by the extent of continuous<br />

canopy within natural forest (Montgomery and<br />

Sunquist, 1978).<br />

Previous authors have assumed the distribution of<br />

B. variegatus to include nearly the entire lowland territory<br />

of Colombia (Wetzel, 1982; Eisenberg, 1989;<br />

Emmons and Feer, 1999; Fonseca and Aguiar, 2004).<br />

However, we have developed what we believe to be a<br />

more accurate and detailed assessment of its range,<br />

based on interviews with local hunters, government<br />

officials and other researchers, as well as personal<br />

observations and our efforts to track the origin of<br />

confiscated animals. Based on this information, we<br />

believe that variegated sloths are limited to some areas<br />

of the northern Caribbean region, certain localities in<br />

the inter-Andean valleys, and the Pacific and Amazonian<br />

regions. We have combined presence data<br />

from Anderson and Handley (2001) with our own<br />

unpublished data to produce a preliminary model<br />

of distribution using BIOCLIM (Busby, 1991) and<br />

DIVA-GIS (Hijmans, 2005) that we believe presents<br />

the probable current distribution of B. variegatus<br />

(Fig. 2).<br />

C. hoffmanni has a wider distribution, ranging from<br />

the northern Caribbean coast to the south along the<br />

Pacific coast, as well as in the central Andean regions<br />

(Wetzel, 1982). In Colombia there are two distinct<br />

phenotypes of C. hoffmanni; one is found in lower,<br />

warmer areas below 1500 m, while the other is typical<br />

of higher and cooler zones between 1500 and<br />

3000 m (Moreno, 2003b). These phenotypes may<br />

correspond to the subspecies C. h. capitalis and<br />

C. h. agustinus, respectively (Wetzel, 1982). C. didactylus<br />

has been reported from the Orinoco and Amazon<br />

regions (Wetzel, 1982; Eisenberg, 1989; Emmons and<br />

Feer, 1999), but this species has been little studied<br />

in Colombia.<br />

FIGURE 1. Main natural regions of Colombia. Map developed from<br />

IAvH (2005a) and IGAC (2002). Arid and semiarid areas correspond<br />

to lowlands dominated by xerophytic or subxerophytic vegetation.<br />

Savannahs are lowlands with marked dry-wet seasons; they are characterized<br />

by shrub vegetation and abundant wetlands. The Andean<br />

region is comprised of a great diversity of montane ecosystems with<br />

multiple vegetation assemblies, ranging from 500 to 3900 m above<br />

sea level. Rainforest is evergreen hygrophilous with exuberant stratified<br />

vegetation, rich in lianas and epiphytes. Transformed areas are<br />

primarily used for intensive agriculture and ranching (IGAC, 2002).<br />

10<br />

<strong>Edentata</strong> no. 7 • May 2006

Threats to <strong>Sloth</strong> Survival<br />

Habitat destruction and fragmentation<br />

As with too many tropical species, the greatest threat<br />

to the survival of sloths in Colombia is the destruction<br />

of their natural habitat (Chiarello, 1999). Owing<br />

to the constant expansion of ranching, agriculture<br />

and urban areas, over 100,000 ha of natural forest are<br />

destroyed every year in Colombia (IDEAM, 2004),<br />

with immense wildlife mortality as a direct result.<br />

<strong>Sloth</strong>s sometimes die in large numbers in incidents<br />

that go unreported by the media, and unnoticed or<br />

ignored by Colombian wildlife agencies and police. 1<br />

One such case was reported in the newspaper El<br />

Colombiano (Machado, 2002) in Necoclí, Department<br />

of Antioquia, where an estimated 600 B. variegatus<br />

were displaced by the destruction of their<br />

habitat, forcing them into open grassland and beaches<br />

where they suffered from starvation, dehydration and<br />

parasite infestation. People from the local communities<br />

took action to rescue the sloths on the beaches<br />

themselves, one by one, without assistance from the<br />

local authorities (R. Villarta, pers. comm.).<br />

At the sloth rehabilitation center of the UNAU Foundation,<br />

we are often called to nearby semi-urban areas<br />

to rescue two-toed sloths (C. hoffmanni) that have<br />

been injured in a variety of ways — hit by cars, stoned<br />

by children, or suffering from electrical shocks — as<br />

well as others that appear to be dispersing from lost<br />

habitat. All these cases are ultimately related to the<br />

destruction of remnant patches of natural forests<br />

(Moreno, 2003a). We have not had rescue calls for<br />

the other two species of sloth; C. didactylus and B.<br />

variegatus do not naturally occur near the city of<br />

Medellín where the Foundation is located. We have<br />

had similar cases reported by veterinarians, however,<br />

and some individuals of these species have been sent<br />

to us from regions throughout the country.<br />

In general, B. variegatus are more vulnerable than<br />

other sloths to habitat disruption. Their reduced<br />

mobility, small home range, and their more gregarious<br />

and diurnal habits make them more sensitive to<br />

forest loss, which may account for their disappearance<br />

from many regions of their former distribution.<br />

1<br />

Colombian wildlife agencies are represented locally by<br />

“autonomous regional corporations” which have the responsibility<br />

of administering all natural resources except fish.<br />

There are 30 of these corporations throughout the country,<br />

working under the general guidelines established by the Environmental<br />

Ministry (Ministerio de Ambiente, Vivienda y<br />

Desarrollo Territorial).<br />

FIGURE 2. Preliminary BIOCLIM model of the current distribution of<br />

B. variegatus in Colombia.<br />

Unlike other arboreal mammals, a variegated sloth is<br />

likely to remain within a tree until it is cut down;<br />

this is because their instinctive reaction to a threat<br />

is to hold still rather than to flee (pers. obs.). Once<br />

on the ground, with no sheltering forest nearby, they<br />

are exposed to starvation, predators and hunting. The<br />

northern lowland rainforest and northern savannah<br />

dry forest have been widely cleared for pasture and<br />

croplands (IDEAM, 2004), seriously compromising<br />

the survival of B. variegatus in those areas. Only in<br />

the Pacific lowland rainforest are there still extensive<br />

reaches of continuous canopy.<br />

Choloepus hoffmanni, on the other hand, has larger<br />

home ranges, is more mobile, nocturnal, solitary and<br />

aggressive, and is thus much more adaptable to habitat<br />

alteration. We have seen individuals in a diversity<br />

of habitats, frequently isolated and disturbed,<br />

such as small patches of secondary forest (less than<br />

10 ha) near urban centers. We have also found them<br />

in patches of remnant tropical dry forest in the midst<br />

of cattle ranches. But C. hoffmanni shares the same<br />

forest habitat as B. variegatus, and so it is exposed<br />

to the same threats and alterations. Habitat loss<br />

and fragmentation affect the montane phenotype of<br />

C. hoffmanni in particular (IDEAM, 2004).<br />

There is little published information on C. didactylus,<br />

but its distribution within Colombia follows the lowland<br />

rainforest of the upper Amazon basin (Fonseca<br />

and Aguiar, 2004), which so far has suffered compar-<br />

11

atively little deforestation (IDEAM, 2004). Based on<br />

the extent of its remaining habitat, C. didactylus may<br />

be in the best situation of all the Colombian sloths.<br />

Despite this flexibility, habitat fragmentation is a<br />

critical threat for all three species of sloths in Colombia.<br />

Their adaptations to an arboreal life make them<br />

exceptionally vulnerable when away from the trees,<br />

and open reaches of grassland, crops or urban infrastructure<br />

become insurmountable barriers for them.<br />

Small forest fragments are unlikely to contain viable<br />

populations due to the small genetic pool (Groom et<br />

al., 2005).<br />

Illegal trade in sloths<br />

Every year in Colombia, hundreds of young twoand<br />

three-toed sloths are taken from their mothers<br />

by poachers. Traffickers buy young sloths from children,<br />

who often take them from deforested areas. The<br />

mother sloths are often mistreated and sometimes<br />

killed for their meat. This is not limited to sloths<br />

alone; any wild animal that can be caught is also<br />

used, including monkeys (Alouatta, Ateles, Cebus and<br />

Saguinus), parrots (Aratinga, Pionus and Amazona),<br />

macaws (Ara) and other xenarthrans such as Tamandua<br />

and Cyclopes. Once taken from the forest, animals<br />

are brought to improvised shelters with inadequate<br />

housing, feeding and sanitary conditions, and are sold<br />

to Colombians traveling between the interior and the<br />

coast on vacation (Moreno, 2003a). The price of a<br />

young sloth starts at the local equivalent of US$30,<br />

but with a little bargaining one may be bought for<br />

less than US$5 (pers. obs.). Neither the sellers nor the<br />

buyers understand the nutritional and environmental<br />

needs of these animals, and so the stress of their capture<br />

and captivity ultimately leads to their deaths. This<br />

commerce is strictly illegal; although there are no laws<br />

in Colombia that give specific protection to sloths,<br />

all wildlife in the country is protected by a general<br />

law (Decreto 1608/1978) that prohibits the hunting,<br />

possession and traffic of Colombian wildlife.<br />

This trade in sloths is not a new development, but<br />

the number of sloths sold on roadsides has risen in<br />

recent years. The security on national highways has<br />

improved significantly since 2003, bringing greater<br />

numbers of seasonal travelers — and hence creating<br />

greater opportunities for wildlife traffickers. Thanks<br />

in part to extensive educational efforts by the UNAU<br />

Foundation, local and national authorities have taken<br />

an increasing interest in the issues of sloth welfare,<br />

but the trade continues unabated. <strong>Sloth</strong>s appear to be<br />

captured and sold mainly in the northern departments<br />

of Córdoba, Sucre, Bolívar, Atlántico and Magdalena<br />

(Fig. 3, Table 1) (Moreno and Plese, 2004). These<br />

departments are rich in natural resources — but they<br />

are also undergoing rapid transformation, with wetlands<br />

and forests converted for agriculture and cattle<br />

farming. A major highway, La Troncal del Norte,<br />

leads from the interior to the Caribbean coast, passing<br />

through the northern departments and serving<br />

as a conduit for potential buyers on vacation. Local<br />

authorities are unable to exert much control over the<br />

roadside sale of wildlife there, and many sloths change<br />

hands during the summer and winter holidays.<br />

In 2004 in the city of Medellín alone — the second<br />

largest in the country — local police and wildlife<br />

agencies reported the confiscation of 256 mammals<br />

(Moreno et al., 2005). That same year, the UNAU<br />

Foundation received 102 sloths, of which 81 (79.4%)<br />

were B. variegatus and 21 (20.6%) were C. hoffmanni<br />

(Tables 2 and 3). Of these 102 rescued animals, about<br />

70% were newborns or juveniles, with a body weight<br />

of less than 700 g. B. variegatus is the more appealing<br />

species for the wildlife trade; their docile nature and<br />

inherent charm, especially in infants and juveniles,<br />

make for easy sales to unwary buyers. C. didactylus is<br />

much less common in this trade; during the five years<br />

UNAU has been in operation, we have received only<br />

one individual — a juvenile rescued after its mother<br />

FIGURE 3. Sources of illegal traffic, by department, in B. variegatus<br />

and C. hoffmanni in Colombia. The source symbols represent<br />

highway locations or municipalities where sloths were bought. We<br />

collected this information based on reports from buyers who later<br />

regretted their purchases, and from our personal observations during<br />

fieldwork for the UNAU Foundation.<br />

12<br />

<strong>Edentata</strong> no. 7 • May 2006

was killed by a car near the town of Florencia in the<br />

Amazon. The areas where C. didactylus are found are<br />

too remote and have too little tourism for traffic in<br />

this species to be common.<br />

To determine the departments where this traffic is<br />

most prevalent, we analyzed our records for the 274<br />

sloths admitted to the UNAU Foundation between<br />

March 2001 and October 2004. Records without a<br />

known purchase site were not used. We also excluded<br />

records of adult individuals, as these animals come to<br />

the Foundation as result of accidents (road, electrocution)<br />

or other encounters. We sorted the remaining<br />

61 records by department (Table 1).<br />

TABLE 1. Departments of origin for young sloths arriving at the UNAU<br />

Foundation (March 2001–October 2004).<br />

Department Qty. %<br />

Córdoba 25 41%<br />

Antioquia 8 13%<br />

Sucre 7 11%<br />

Atlántico 6 10%<br />

Bolívar 3 5%<br />

Magdalena 3 5%<br />

Huila 2 3%<br />

Risaralda 2 3%<br />

Boyacá 1 2%<br />

Caquetá 1 2%<br />

Chocó 1 2%<br />

Quindío 1 2%<br />

Tolima 1 2%<br />

Total 61 100%<br />

TABLE 2. Number of sloths received at the UNAU Foundation sloth<br />

rehabilitation center in the first five years of its operation.<br />

Year N° of sloths per year Cumulative N° of <strong>Sloth</strong>s<br />

2000 8 8<br />

2001 28 36<br />

2002 36 72<br />

2003 103 175<br />

2004 102 277<br />

TABLE 3. Total sloth mortality at the UNAU Foundation rehabilitation<br />

center during 2004.<br />

B. variegatus C. hoffmanni<br />

Admissions 81 (100%) 21 (100%)<br />

Mortality 68 (84%) 52 (52%)<br />

Survivors 13 (16%) 10 (48%)<br />

The northern departments of Córdoba, Antioquia,<br />

Atlántico, Sucre, Bolívar and Magdalena are the<br />

source of 85% of the young sloths we have received,<br />

most of them victims of a chain of regular traffic.<br />

The remaining 15% come from departments of<br />

the interior. These are mostly C. hoffmanni, and<br />

according to testimonies, they were captured<br />

in chance encounters. Many of these sloths die<br />

unreported in private hands. Very few of them<br />

are given to zoos or a rehabilitation center such<br />

as UNAU.<br />

Although the police may confiscate sloths at highway<br />

checkpoints, or in response to citizen complaints,<br />

most of those we have received were voluntarily surrendered<br />

by the buyers, concerned by their new<br />

pet’s failing health — or by the trouble of keeping it<br />

alive. To some extent, buyers may also be moved by<br />

campaigns undertaken by wildlife agencies and the<br />

UNAU Foundation. Not surprisingly, the mortality<br />

of these sloths is high.<br />

The annual increase in the number of individuals<br />

received at the center results from two factors: first,<br />

the consolidation of the rehabilitation center, and its<br />

increasing recognition by citizens and wildlife authorities;<br />

and second, the increase in the sale of sloths on<br />

the northern highways, as the improvements in overall<br />

security have brought more vacationers out on<br />

the roads.<br />

Rehabilitation<br />

Two factors strongly influence the success of the rehabilitation<br />

process. The first is the body weight of the<br />

animal upon arrival, which depends on its age. Mortality<br />

is very high (about 70%) for individuals weighing<br />

less than 700 g, which corresponds to their first<br />

five months of life. After this age, their chances for<br />

survival improve considerably, and older sloths show<br />

about 30% mortality (Table 4).<br />

The second determining factor is the physical condition<br />

of new arrivals, which is critical during their first<br />

30 days at the rehabilitation center. Most of the mortality<br />

occurs during this period (Table 5), usually as<br />

a direct result of the treatment sloths received from<br />

poachers, salesmen and unsuspecting buyers. Before<br />

a sloth’s arrival at the UNAU Foundation’s rehabilitation<br />

center, it may have been in captivity for some<br />

15 days, during which it was most likely malnourished<br />

and badly cared for. If the young sloth experiences<br />

a violent separation from its mother and is<br />

subsequently mistreated, it is in poor physical condition,<br />

often involving dehydration, starvation, trauma<br />

and disease.<br />

13

TABLE 4. <strong>Sloth</strong> mortality by body weight during 2004.<br />

Body Weight (g) B. variegatus C. hoffmanni<br />

200 –700 44 (65%) 8 (73%)<br />

> 700 24 (35%) 3 (27%)<br />

Mortality 68 (100%) 11 (100%)<br />

TABLE 5. <strong>Sloth</strong> mortality by time in rehabilitation during 2004.<br />

Period in rehabilitation<br />

(days)<br />

B. variegatus C. hoffmanni<br />

< 30 53 (78%) 8 (73%)<br />

> 30 15 (22%) 3 (27%)<br />

Mortality 68 (100%) 11 (100%)<br />

FIGURE 4. A salesman offering a young B. variegatus by the road in<br />

“La Y,” Córdoba. Not knowing otherwise, tourists will often believe<br />

the hucksters’ claims that sloths are easy to feed and maintain.<br />

A health survey of the 277 sloths treated by the<br />

UNAU Foundation showed that respiratory diseases,<br />

such as acute or chronic bronchopneumonia<br />

and lobar pneumonia, are by far the most common<br />

ailment, with 248 cases (90%) in total. Other illnesses<br />

include digestive problems such as diarrhea,<br />

constipation, tympanism and rumen paralysis, with<br />

14 cases (5%); skin problems caused by fungus, bacteria<br />

(Staphylococcus aureus) and external parasites<br />

such as ticks, lice and mites (e.g., Demodex canis),<br />

with 8 cases (3%); and human-induced traumas such<br />

as nail mutilation, filed-down teeth, contusions, electric<br />

shock, burns and other wounds (5 cases; 2%).<br />

Nail polish is commonly used on sloths offered for<br />

sale: poachers use it to prevent young sloths, with<br />

their sharp nails and strong grip, from intimidating<br />

potential buyers. Other sellers will sometimes clip the<br />

nails instead of polishing them, with results as seen in<br />

Fig. 5a. C. hoffmanni have sharp, canine-like molars,<br />

and even very young individuals are able to bite down<br />

hard; thus poachers will sometimes file down the<br />

infants’ teeth, with consequences that may eventually<br />

be fatal. Other generalized traumas are caused by<br />

improper confinement and careless maintenance by<br />

poachers and buyers alike.<br />

Capture myopathy is a complex condition involving<br />

physiological and psychological factors generated<br />

by stressful handling (Kreeger et al., 2002). Infant<br />

and juvenile sloths suffer from immunodepression<br />

as a consequence of the trauma of early separation<br />

from the mother (Brieva et al., 2000). Often they<br />

will also develop digestive problems caused by an<br />

improper diet, especially infants that do not have a<br />

fully developed digestive system. There is no good<br />

substitute for a sloth mother’s natural milk. Pulmonary<br />

problems may also arise, sometimes due to the<br />

inhalation of liquids into the lungs during artificial<br />

feeding. Other pulmonary difficulties may develop<br />

as well, both from overall stress and from their<br />

sudden change in climate — from the warm, lowland<br />

rainforests and savannas to the cooler Andean<br />

regions where most buyers live. Young sloths may<br />

also acquire respiratory ailments from close contact<br />

with humans.<br />

Conservation Status<br />

The conservation status currently assigned to Colombian<br />

sloths by national and international authorities<br />

makes it difficult to enforce their protection. The<br />

most recognized authority, the IUCN Red List, classifies<br />

B. variegatus, C. hoffmanni and C. didactylus as<br />

LC – Least Concern (IUCN, 2006).<br />

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered<br />

Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES)<br />

lists B. variegatus in Appendix II and C. hoffmanni<br />

in Appendix III with no other restrictions, while no<br />

classification is given to C. didactylus (CITES, 2005).<br />

Appendix II includes species not necessarily threatened<br />

with extinction, but for which trade must be<br />

controlled in order to avoid uses incompatible with<br />

their survival. Appendix III contains species that are<br />

protected in at least one country and which has asked<br />

other CITES Parties for assistance in controlling the<br />

trade (CITES, 2005).<br />

A report by the World Conservation Monitoring<br />

Centre of the United Nations Environment Programme<br />

(UNEP-WCMC) on the international<br />

trade in wildlife lists only six individuals of B. variegatus<br />

(1 body, 5 live) for the period 1995–1999, and<br />

provides no information on their origin (UNEP-<br />

WCMC, 2001). It should be noted, however, that<br />

UNEP-WCMC and CITES deal only with the international<br />

species trade, and do not address the issues<br />

of within-country wildlife commerce. We include<br />

14<br />

<strong>Edentata</strong> no. 7 • May 2006

TABLE 6. <strong>Sloth</strong> conservation status according to national and international listing authorities.<br />

Organization B. variegatus C. hoffmanni C. didactylus<br />

IUCN Red List (IUCN, 2006) LC – Least Concern LC – Least Concern LC – Least Concern<br />

NatureServe (InfoNatura, 2004) G5 – Secure G4 – Apparently Secure G4 – Apparently Secure<br />

CITES (CITES, 2005) Appendix II Appendix III (Costa Rica only) None<br />

Ministerio de Ambiente, Colombia (2005) Not listed Not listed Not listed<br />

them here to provide an international perspective<br />

on the traffic in sloths — and because conservation<br />

funds are often conditional on a species being listed<br />

by CITES.<br />

A separate measure of conservation status, developed<br />

by the NGO NatureServe, lists B. variegatus as G5<br />

(Secure) and both species of Choloepus as G4 (Apparently<br />

Secure) (InfoNatura, 2004). Information from<br />

all three threat classification systems is summarized in<br />

Table 6. None of the three sloth species is included on<br />

the List of Threatened Mammals of Colombia (Ministerio<br />

de Ambiente, 2005).<br />

Discussion<br />

The international classifications of sloth conservation<br />

status are not representative of the local situation in<br />

Colombia. Other countries such as Bolivia, Costa<br />

Rica and Brazil face similar threats to their own sloth<br />

populations, and have ongoing rehabilitation programs<br />

for these species — indicating there is pressure<br />

on them as well.<br />

The most recent distribution maps for the sloths, presented<br />

by Fonseca and Aguiar (2004), do not differ<br />

much from the maps provided by Wetzel (1982).<br />

These maps are generalized and do not represent the<br />

actual distribution of the three species in Colombia.<br />

For example, these sources indicate that B. variegatus<br />

is present throughout the territory of Colombia, in<br />

significant contrast with the preliminary results of our<br />

BIOCLIM model (Fig. 2).<br />

Likewise, conservation assessments are sometimes<br />

based on isolated reports that may not always be representative<br />

of a species’ ecology as a whole. Eisenberg<br />

and Thorington (1973) reported sloths to comprise<br />

as much as 40% of the biomass of mammals on Barro<br />

Colorado Island, and suggested that “Bradypus exists<br />

at the highest numerical density of any large, arboreal<br />

mammal” in the Neotropics. However, the situation<br />

at Barro Colorado Island is almost certainly different<br />

from conditions prevailing across the majority of the<br />

species’ range. In addition, B. variegatus is sometimes<br />

gregarious, congregating in large numbers during<br />

a<br />

b<br />

c<br />

d<br />

FIGURE 5. Frequent traumas on trafficked B. variegatus: a. mutilation of the nails; b. severe respiratory disease; c. laceration caused by fungus;<br />

d. trauma to the left eye.<br />

15

mating seasons and at seasonal feeding grounds,<br />

giving a false impression of abundance (pers. obs.).<br />

Thus we would caution researchers, conservationists<br />

and decision-makers on the danger of taking these<br />

generalizations too literally, as this may lead to unnoticed<br />

local extinctions. The current situation of sloths<br />

in Colombia may also hold true for other, less-noted<br />

species without organizations dedicated to their survival,<br />

such as the silky anteater (Cyclopes didactylus).<br />

At present there are very few organizations in Colombia,<br />

perhaps a dozen all told, which are working on<br />

the conservation of specific genera.<br />

The Alexander von Humboldt Institute for the Investigation<br />

of Biological Resources (IAvH) is a public<br />

corporation, linked to the Colombian Ministry of<br />

the Environment, which tracks the threat status of<br />

all Colombian fauna. The IAvH lists 16 criteria for<br />

a species at risk of extinction (IAvH, 2005b). Six of<br />

these criteria, we believe, are applicable to Bradypus<br />

and Choloepus in Colombia:<br />

• Species whose populations are known to be<br />

declining;<br />

• Species with low population density;<br />

• Species with a reduced ability to disperse to<br />

new environments;<br />

• Species that are habitat specialists;<br />

• Species that suffer pressure from overexploitation;<br />

and<br />

• Species with close relatives extinct or currently<br />

threatened.<br />

The Colombian Ministry of the Environment does<br />

not list any of these three sloth species as being of<br />

conservation concern (Table 6), probably because<br />

there are no long-term studies to demonstrate<br />

cause for concern. For Colombia and for the international<br />

community, sloths are not focal species<br />

because they are not listed as threatened or potentially<br />

threatened. There are no formal estimates of<br />

sloth densities in Colombia, and this would be the<br />

first step in order to present any estimates of the<br />

total population.<br />

Funds for species protection are always scarce, and<br />

generally go to those species listed as high risk in<br />

IUCN categories, while those that are Least Concern<br />

or Data Deficient are largely ignored. This circle — in<br />

which Data Deficient species receive little attention,<br />

and lack of funding precludes new research — traps<br />

investigators in a frustrating situation, as they are witness<br />

to the worsening situation of many of these species,<br />

but are unable to address it themselves.<br />

At a local level, the limited efforts by police and wildlife<br />

agencies to control the wildlife trade are of no<br />

substantial help. A report from the Procuraduría General<br />

de la Nación, the Colombian Attorney General’s<br />

Office, denounces the lack of legal instruments to<br />

regulate the post-confiscation management of wildlife<br />

in Colombia, as well as insufficient infrastructure and<br />

the lack of reliable statistics on confiscation and illegal<br />