1) Vitamin D For Chronic Pain - Pain Treatment Topics.org

1) Vitamin D For Chronic Pain - Pain Treatment Topics.org

1) Vitamin D For Chronic Pain - Pain Treatment Topics.org

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

VITAMIN D FOR<br />

CHRONIC PAIN<br />

According to a comprehensive review of the clinical<br />

research evidence, helping certain patients overcome<br />

chronic musculoskeletal pain and fatigue syndromes<br />

may be as simple, well tolerated, and inexpensive as<br />

a daily supplement of vitamin D.<br />

By Stewart B. Leavitt, MA, PhD<br />

Editor’s note: This article is adapted from the author’s peer-reviewed research report, <strong>Vitamin</strong> D—<br />

A Neglected ‘Analgesic’ for <strong>Chronic</strong> Musculoskeletal <strong>Pain</strong>, from <strong>Pain</strong> <strong>Treatment</strong> <strong>Topics</strong>. The<br />

full report, along with a special brochure for patients, is available at www.pain-topics.<strong>org</strong>/<strong>Vitamin</strong>D.<br />

FIGURE 1. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D Metabolism<br />

Sunlight (UVB)<br />

Synthesis<br />

in Skin<br />

Cholecalciferol (D 3 )<br />

25(OH)D<br />

1,25(OH) 2 D<br />

Metabolism<br />

in Liver<br />

25-hydroxyvitamin D<br />

(calcidiol)<br />

1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D<br />

(calcitriol – active)<br />

Biological Actions<br />

Certain Foods<br />

& Supplements<br />

Ergocalciferol (D 2 )<br />

Cholecalciferol (D 3 )<br />

Metabolism<br />

in Kidney<br />

Binding to<br />

<strong>Vitamin</strong> D Receptors<br />

Standing apart from the various other essential nutrients,<br />

vitamin D was spotlighted recently as having special therapeutic<br />

potential. This has important implications for the<br />

management of chronic musculoskeletal pain and fatigue<br />

syndromes.<br />

During this past June 2008, news-media headlines heralded<br />

recent clinical research that revealed benefits of vitamin D for<br />

preventing type 1 diabetes, 1 promoting survival from certain<br />

cancers, 2 and decreasing the risks of coronary heart disease. 3<br />

Overlooked, however, was the traditional role of vitamin D in<br />

promoting musculoskeletal health and the considerable evidence<br />

demonstrating advantages of vitamin D therapy in helping to<br />

alleviate chronic muscle, bone and joint aches, and pains of<br />

various types.<br />

<strong>Chronic</strong> pain—persisting more than 3 months—is a common<br />

problem leading patients to seek medical care. 4-7 In many cases,<br />

the causes are nonspecific, without evidence of injury, disease, or<br />

neurological or anatomical defect. 8,9 However, according to<br />

extensive clinical research examining adult patients of all ages,<br />

inadequate concentrations of vitamin D have been linked to nonspecific<br />

muscle, bone, or joint pain, muscle weakness or fatigue,<br />

fibromyalgia syndrome, rheumatic disorders, osteoarthritis,<br />

hyperesthesia, migraine headaches, and other chronic somatic<br />

complaints. It also has been implicated in the mood disturbances<br />

of chronic fatigue syndrome and seasonal affective disorder.<br />

Although further research would be helpful, current best<br />

evidence demonstrates that supplemental vitamin D can help<br />

many patients who have been unresponsive to other therapies<br />

for pain. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D therapy is easy for patients to self-administer,<br />

well-tolerated, and very economical.<br />

24 Practical PAIN MANAGEMENT, July/August 2008<br />

©2008 PPM Communications, Inc. Reprinted with permission.

<strong>Vitamin</strong> D for <strong>Chronic</strong> <strong>Pain</strong><br />

It must be emphasized that vitamin D is not<br />

a pharmaceutical analgesic in the sense of<br />

fostering relatively immediate pain relief, and<br />

expectations along those lines would be unrealistic.<br />

Because <strong>Vitamin</strong> D supplementation<br />

addresses underlying processes, it may take<br />

months to facilitate pain relief, which can range<br />

from partial to complete. Furthermore, vitamin<br />

D supplementation is not proposed as a panacea<br />

or as a replacement for other pain treatment<br />

modalities that may benefit patient care.<br />

<strong>Vitamin</strong> D and ‘D-ficiency’<br />

Pharmacology. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D comprises a group of<br />

fat-soluble micronutrients with two major forms:<br />

D 2 (ergocalciferol) and D 3 (cholecalciferol) 10,11<br />

(see Figure 1). <strong>Vitamin</strong> D 3 is synthesized in the<br />

skin via exposure of endogenous 7-dehydrocholesterol<br />

to direct ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation<br />

in sunlight and is also obtained to a small extent<br />

in the diet (see Table 1). In many countries, some<br />

foods are fortified with vitamin D 3 , which is the<br />

form used in most nutritional supplements. 14,20<br />

<strong>Vitamin</strong> D 2 , on the other hand, is found in<br />

relatively few foods or supplements. 14<br />

Following vitamin D synthesis in the skin or<br />

other intake, some of it is stored in adipose<br />

tissue, skeletal muscle, and many <strong>org</strong>ans, 19 while<br />

a relatively small portion undergoes a two-stage<br />

process of metabolism (see Figure 1). First, D 2<br />

and/or D 3 are metabolized via hydroxylation in<br />

the liver to form 25-hydroxyvitamin D, abbreviated<br />

as 25(OH)D (also called calcidiol). 10,14,18,21,22<br />

This has minimal biological activity and serum<br />

concentrations of 25(OH)D accumulate gradually,<br />

plateauing at steady-state levels by about 40<br />

days 19,23,24 to 90 days. 25,26<br />

The 25(OH)D metabolite is converted primarily<br />

in the kidneys via further hydroxylation to<br />

1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, abbreviated as<br />

1,25(OH) 2 D (also called calcitriol). It is the most<br />

important and biologically-active vitamin D<br />

metabolite with a short half-life of only 4 to 6<br />

hours 27 but can remain active for 3 to 5 days. 15,20<br />

A central role of vitamin D—via its active<br />

1,25(OH) 2 D metabolite—is to facilitate the<br />

absorption of calcium from the intestine and<br />

help maintain normal concentrations of this<br />

vital agent. Equally important, 1,25(OH) 2 D<br />

sustains a wide range of metabolic and physiologic<br />

functions throughout the body. 28<br />

<strong>Vitamin</strong> D actually is misclassified as a<br />

vitamin; it may be more appropriately considered<br />

a prohormone and its active 1,25(OH) 2 D<br />

metabolite—with its own receptors found in<br />

practically every human tissue—functions as a<br />

hormone. These vitamin D receptors, or VDRs,<br />

may affect the function of up to 1000 different<br />

genes 18,22,29,30,31 helping to control cell growth or<br />

differentiation. The VDRs themselves can differ<br />

Source<br />

TABLE 1: Sources of <strong>Vitamin</strong> D<br />

<strong>Vitamin</strong> D 2 and D 3 Sources<br />

<strong>Vitamin</strong> D Content<br />

Higher-Yield Natural Sources<br />

Exposure to sunlight, ultraviolet B radiation<br />

(0.5 minimal erythemal dose) † 3000–10,000 IU D 3<br />

Salmon fresh, wild (3.5 oz*) 600–1000 IU D 3<br />

Salmon fresh, farmed (3.5 oz) 100–250 IU D 3<br />

Salmon canned (3.5 oz) 300–600 IU D 3<br />

Herring, pickled (3.5 oz) 680 IU D 3<br />

Catfish, poached (3.5 oz) 500 IU D 3<br />

Sardines, canned (3.5 oz) 200–360 IU D 3<br />

Mackerel, canned (3.5 oz) 200–450 IU D 3<br />

Tuna, canned (3.6 oz) 200–360 IU D 3<br />

Cod liver oil (1 tsp / 0.17 oz) 400–1400 IU D 3<br />

Eastern oysters, steamed (3.5 oz) 642 IU D 3<br />

Shiitake mushrooms fresh (3.5 oz) 100 IU D 2<br />

Shiitake mushrooms sun-dried (3.5 oz) 1600 IU D 2<br />

Egg yolk, fresh 20–148 IU D 3<br />

<strong>For</strong>tified Foods<br />

<strong>For</strong>tified milk 60–100 IU/8 oz, usually D 3<br />

<strong>For</strong>tified orange juice 60–100 IU/8 oz usually D 3<br />

Infant formulas 60–100 IU/8 oz usually D 3<br />

<strong>For</strong>tified yogurts 100 IU/8 oz, usually D 3<br />

<strong>For</strong>tified butter 50 IU/3.5 oz, usually D 3<br />

<strong>For</strong>tified margarine 430 IU/3.5 oz, usually D 3<br />

<strong>For</strong>tified cheeses 100 IU/3 oz, usually D 3<br />

<strong>For</strong>tified breakfast cereals 60-100 IU/serving, usually D 3<br />

Food labels often express vitamin D content only as % of daily value, so it is usually<br />

unknown what the exact amount is in International Units (IU).<br />

Supplements<br />

Over The Counter/Internet<br />

‡<br />

Multivitamin (including vitamin D) 400–800 IU vitamin D 2 or D 3<br />

<strong>Vitamin</strong> D (tablets, capsules)<br />

Various doses 400–50,000 IU<br />

(primarily D 3 )<br />

Prescription/Pharmaceutical<br />

<strong>Vitamin</strong> D 2 (ergocalciferol)<br />

50,000 IU/capsule<br />

Drisdol ® , Calciferol ® , others(vitamin D 2 )<br />

liquid supplements<br />

8000 IU/mL<br />

Rocaltrol ® , Calcigex ® , others (1,25[OH] 2 D)<br />

available outside US<br />

0.25-0.5 mcg capsules<br />

1 mcg/mL solution<br />

* 1 oz = 28.3 grams = 29.6 mL; 1 IU = 40 mcg (microgram)<br />

† A 0.5 minimal erythemal dose of UVB radiation would be absorbed after about 10-15 minutes<br />

of exposure of arms and legs to direct sunlight (depending on time of day, season, latitude,<br />

and skin sensitivity). Dark-skinned persons would require longer.<br />

‡ Ergocalciferol on product label signifies D 2 ; cholecalciferol signifies D 3 .<br />

References: Calcitriol 12 ; Ergocalciferol 13 ; Holick 14 ; Marcus 15 ; ODS 16 ; Singh 17 ; Tavera-Mendoza<br />

and White 18 ; and Vieth 19 25<br />

Practical PAIN MANAGEMENT, July/August 2008<br />

©2008 PPM Communications, Inc. Reprinted with permission.

<strong>Vitamin</strong> D for <strong>Chronic</strong> <strong>Pain</strong><br />

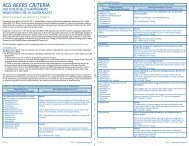

TABLE 2: DEFINING ADEQUATE<br />

25(OH)D CONCENTRATIONS<br />

25(OH)D Concentrations<br />

Major Metabolite of <strong>Vitamin</strong> D from D 2 or D 3<br />

Deficient 150 ng/mL<br />

In some literature 25(OH)D is expressed as nmol/L.<br />

The conversion formula is: 1 ng/mL = 2.5 nmol/L<br />

or 1 nmol/L = 0.4 ng/mL.<br />

References: Heaney 39 ; Heaney et al 42 ; Holick 14 ; Reginster et<br />

al 41 ; Tavera-Mendoza and White 18 ; Vieth 24<br />

in their genetic makeup (poly-morphism)<br />

and activity, which may account for<br />

varying individual responses to vitamin D<br />

therapy. 32,33<br />

The discovery of vitamin D receptors<br />

in many tissues besides intestine and<br />

bone—including heart, pancreas, breast,<br />

prostate, lymphocytes, and other<br />

tissues—implies that vitamin D supplementation<br />

might have applications for<br />

treating a number of disorders. These<br />

include autoimmune diseases, diabetes,<br />

cardiovascular disease, psoriasis, hypoparathyroidism,<br />

renal osteodystrophy,<br />

and possibly leukemia and cancers of the<br />

breast, prostate, or colon. 1-3,20,34-37 Research<br />

is ongoing in these areas.<br />

If vitamin D production or intake is<br />

diminished, reabsorption of vitamin D<br />

from tissue-storage reservoirs can<br />

sustain conversion to 25(OH)D and the<br />

1,25(OH) 2 D metabolite for several<br />

months. However, an abundant supply of<br />

vitamin D during certain times, such as<br />

from summer sun exposure, does not<br />

deter its complete depletion during<br />

periods of lean intake, such as during<br />

winter months. 19<br />

Numerous individual factors may affect<br />

the status of vitamin D and its metabolites<br />

in the body. Synthesis of vitamin D 3 in the<br />

skin in reaction to UVB exposure is a selflimiting<br />

reaction that achieves equilibrium<br />

within 20 to 25 minutes of exposure<br />

to strong sunlight in persons with white<br />

skin, with no net increase in D 3 production<br />

after that. 19 Persons with darker skin<br />

require longer sun exposure, but the total<br />

yield in D 3 is the same. Age is another<br />

limiting factor, and it is more difficult for<br />

older persons to acquire adequate vitamin<br />

D from UVB radiation. 21,28<br />

Adequate 25(OH)D Concentration.<br />

Most researchers agree that a minimum<br />

25(OH)D serum level of about 30 ng/mL<br />

or more is necessary for favorable calcium<br />

absorption and good health. 14,38-41 Optimal<br />

25(OH)D concentrations are considered<br />

to range from 30 ng/mL to 50 ng/mL (see<br />

Table 2). 20,35,36,42-44<br />

Most definitions of deficiency stress<br />

that circulating 25(OH)D concentrations<br />

of 100 ng/mL as possibly toxic, but this<br />

could be overly conservative and reported<br />

reference ranges are not always consistent<br />

from one laboratory to another.<br />

General Prevalence of “D-ficiency.”<br />

There is a growing consensus that vitamin<br />

D inadequacies in the general population—or<br />

what Holick [2004a] 112 has<br />

broadly labeled “D-ficiency”—are much<br />

more common and severe than might be<br />

imagined. This has been extensively<br />

studied and, according to the research<br />

evidence, it may be assumed in almost any<br />

clinical practice that at least 50% of<br />

patients will have 25(OH)D concentrations<br />

below 30 ng/mL, the lower limit of<br />

the optimal range. In many instances, the<br />

percentage of patients with vitamin D<br />

insufficiency will be much greater, and a<br />

significant proportion of them may have<br />

more serious deficiencies of

<strong>Vitamin</strong> D for <strong>Chronic</strong> <strong>Pain</strong><br />

28 Practical PAIN MANAGEMENT, July/August 2008<br />

©2008 PPM Communications, Inc. Reprinted with permission.

<strong>Vitamin</strong> D for <strong>Chronic</strong> <strong>Pain</strong><br />

Practical PAIN MANAGEMENT, July/August 2008<br />

©2008 PPM Communications, Inc. Reprinted with permission.<br />

29

<strong>Vitamin</strong> D for <strong>Chronic</strong> <strong>Pain</strong><br />

weakness. 20 Therefore, experts recommend that vitamin D<br />

deficiency and its potential for associated osteomalacia should<br />

be considered in the differential diagnosis of all patients with<br />

chronic musculoskeletal pain, muscle weakness or fatigue,<br />

fibromyalgia, or chronic fatigue syndrome. 27<br />

Table 3 summarizes 22 clinical investigations of vitamin D in<br />

patients with chronic musculoskeletal-related pain. These<br />

studies were conducted in various countries and included<br />

approximately 3,670 patients representing diverse populations<br />

and age groups.<br />

The percentage of patients with pain having inadequate<br />

vitamin D concentrations ranged from 48% to 100%, depending<br />

on patient selection and the definition of 25(OH)D<br />

“deficiency.” In most cases,

<strong>Vitamin</strong> D for <strong>Chronic</strong> <strong>Pain</strong><br />

study of supplemental vitamin D versus broad-spectrum light<br />

therapy (phototherapy), which is often recommend for patients<br />

with SAD, vitamin D produced significant improvements in all<br />

outcome measures of depression, whereas the phototherapy<br />

group showed no significant changes. 97<br />

In a randomized, placebo-controlled study that included<br />

patients with clinical depression, those administered supplemental<br />

vitamin D had significantly enhanced mood and a reduction<br />

in negative-affect symptoms. 98 In similar investigations,<br />

more adequate vitamin D concentrations were associated with<br />

better physical, social, and mental functioning as measured by<br />

quality-of-life assessment instruments, 99 and improved scores on<br />

an assessment of well-being. 100<br />

In sum, while further research is needed, the potential benefits<br />

of vitamin D supplementation may be expanded from its role<br />

in supporting bone and muscle health to that of a complex<br />

hormonal system benefiting other conditions often associated<br />

with chronic pain. 31<br />

Assessing <strong>Vitamin</strong> D Status<br />

Clinical Indicators. From a clinical perspective, a number of<br />

factors may suggest that chronic musculoskeletal pain and<br />

related problems may be due to inadequate vitamin D intake.<br />

Researchers have stressed that the “gold standard” for a<br />

presumptive diagnosis of inadequate vitamin D is a review of<br />

patient history, lifestyle, and dietary habits that might pose risks<br />

for deficiency. 101 Along with this, indicators of defects in bone<br />

metabolism may include chronic muscle, bone, or joint pain, as<br />

well as persistent muscle weakness, fatigue, and possibly difficulty<br />

walking. 20,101,102 Radiological changes potentially associated<br />

with osteomalacia are seen only in advanced stages. 20,103<br />

Signs/symptoms of calcium deficiency (hypocalcemia) due to<br />

vitamin D deficiencies relate to neuromuscular irritability. Patients<br />

sometimes complain of paresthesias (numbness, tingling, prickling,<br />

or burning) in their lips, tongue, fingertips, and/or toes,<br />

along with fatigue and anxiety. Muscles can be painfully achy,<br />

progressing to cramps or spasms. 104-107 Lethargy, poor appetite,<br />

and mental confusion may be part of the syndrome. 104<br />

The diverse signs and symptoms may be erroneously attributed<br />

to other causes. Holick 14,44 and others 51,76 caution that osteomalacia<br />

due to vitamin D deficiency can be misdiagnosed as<br />

chronic fatigue syndrome, arthritis or rheumatic disease, depression,<br />

or fibromyalgia.<br />

Biochemical Markers. Laboratory assessments usually pertain<br />

to the measurement of biomarkers that could denote osteomalacic<br />

processes, including: 108<br />

• Serum 25(OH)D, total serum calcium (Ca), and phosphate<br />

(PO) are decreased to below normal ranges;<br />

• Parathyroid hormone (PTH) and total alkaline phosphatase<br />

(ALP) are elevated.<br />

It must be understood that there are limitations to the various<br />

laboratory assays in terms of their accuracy and/or helpfulness<br />

in making or confirming a diagnosis. Assessing ALP (a surrogate<br />

marker for bone turnover), PO, or Ca are not reliable<br />

predictors of inadequate 25(OH)D concentrations or underlying<br />

osteomalacic processes. 28,101 Up to 20% of patients with<br />

25(OH)D deficiency and elevated PTH may have normal Ca,<br />

PO, and ALP levels. 74,108<br />

It is generally believed that elevations of PTH may be a<br />

suitable biomarker of histological osteomalacia since, at the<br />

least, secondary hyperparathyroidism seeks to correct calcium<br />

deficits via bone resorption. A diagnosis of inadequate vitamin<br />

D with osteomalacic involvement to some extent could be<br />

presumed if PTH is elevated in association with low calcium<br />

levels, which also would serve to exclude patients with primary<br />

hyperparathyroidism due to other causes. 108<br />

Various assays for determining 25(OH)D concentrations in<br />

serum have relatively recently become available from commercial<br />

laboratories. 39,109 Circulating 25(OH)D reflects both D 2 plus<br />

D 3 intake, but not 1,25(OH) 2 D concentrations. Measuring<br />

1,25(OH) 2 D is not recommended because it can be a poor or<br />

misleading indicator of overall vitamin D status. 14,28,107<br />

There are some concerns about the validity and utility of<br />

25(OH)D assays, which also can be relatively expensive. 108<br />

Several testing methods are available and there can be significantly<br />

large differences in results from one laboratory to the<br />

next, as well as stark variations across types of assays. 21,39,46,110 Error<br />

rates can be high and the reference ranges reported may be<br />

confusing or unhelpful. These concerns should not completely<br />

deter testing for biomarkers related to vitamin D deficiency.<br />

Rather, informed healthcare providers need to consider test<br />

limitations and their objectives in using such measures, keeping<br />

in mind that patient-centered care focuses on individual needs<br />

rather than relying solely on laboratory values for guidance.<br />

While severe deficiencies in 25(OH)D and unambiguous clinical<br />

signs of osteomalacia relate most clearly to musculoskeletal<br />

pain, less severe vitamin D inadequacies are often unrecognized<br />

but nevertheless contributing sources of nociception in patients<br />

with chronic pain. 60 This has been proposed as a “subclinical”<br />

effect of vitamin D inadequacy, since subjective musculoskeletal<br />

pain or weakness develops prior to the emergence of more objective<br />

clinical indicators. 54,76,111<br />

Lotfi et al 54 proposed that in some persons even slight deficits<br />

of 25(OH)D can produce secondary hyperparathyroidism to a<br />

degree that manifests as musculoskeletal pain and/or weakness.<br />

Although vitamin D inadequacy may not be extreme enough to<br />

produce clinically diagnosable osteomalacia, it can still cause<br />

enough PTH elevation to generate increased bone turnover and<br />

loss, increased risk of microfractures, and pain or myalgia.<br />

As Holick 112 has suggested, either the level of 25(OH)D is<br />

adequate for the individual patient, or it is not. If it is inadequate,<br />

subclinical osteomalacia along with multiple forms of<br />

chronic pain and myopathy may emerge and the extent of the<br />

25(OH)D deficit in nanograms-per-milliliter may not matter –<br />

as long as the shortfall is corrected to the extent necessary.<br />

<strong>Vitamin</strong> D Therapy<br />

<strong>Vitamin</strong> D Intake in Healthy Persons. In 1997, the U.S. Institute<br />

of Medicine determined that there was insufficient data to<br />

specify a Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) for vitamin D.<br />

Instead, the <strong>org</strong>anization developed very conservative Adequate<br />

Intake (AI) values of 200 IU to 600 IU per day of vitamin D,<br />

based on an assumption that as people age they would need<br />

extra vitamin D supplementation 16,113 (see Table 4).<br />

According to the most recent 2005 Dietary Guidelines for<br />

Americans from the U.S. government, 114 and expert recommendations,<br />

14,18,24,42,58 healthy children and adults of any age should<br />

consume no less than 1000 IU/day of vitamin D 3 to reach and<br />

maintain minimum serum 25(OH)D concentrations of at least<br />

32 Practical PAIN MANAGEMENT, July/August 2008<br />

©2008 PPM Communications, Inc. Reprinted with permission.

<strong>Vitamin</strong> D for <strong>Chronic</strong> <strong>Pain</strong><br />

30 to 32 ng/mL. However, this may be inadequate.<br />

Clinical research trials have demonstrated that 1000 IU/day<br />

of vitamin D 3 produces only modest increases in 25(OH)D that<br />

can be inconsequential for achieving and maintaining optimal<br />

concentrations of 30 ng/mL or more in some persons. 26,29 Vieth<br />

and colleagues 26 demonstrated that 4000 IU/day D 3 could be<br />

safe and more effective in producing desired outcomes. Several<br />

general principles emerge from the accumulated research to<br />

date 19,21,23,25,26,39,46,100,115,116,117,118 :<br />

• Concentrations of 25(OH)D are not increased in direct<br />

proportion to the amount of supplementation increase.<br />

<strong>For</strong> example, tripling the D 3 dose—such as going from 600<br />

IU/day to 1800 IU/day—does not increase the concentration<br />

of 25(OH)D by threefold.<br />

• Any increase in 25(OH)D is also dependent on the concentration<br />

of this metabolite at the start of treatment. At<br />

equivalent vitamin D doses, patients with more severe<br />

baseline inadequacies will have larger, more rapid increases<br />

in 25(OH)D concentrations.<br />

• What might be considered large doses of vitamin D 3 by<br />

some practitioners do not produce proportionately large<br />

increases in 25(OH)D concentrations, depending on the<br />

amount of dose and duration of administration. <strong>For</strong> example,<br />

a single 50,000 IU dose of D 3 may produce a significantly<br />

smaller increase in 25(OH)D than 2000 IU given<br />

daily over time, and the increases from either of these<br />

could be modest.<br />

• However, it must be noted that continuous megadoses of<br />

vitamin D (eg, >50,000 IU) could produce robust, possibly<br />

toxic, increases in 25(OH)D concentrations over time.<br />

In everyday practice, exceptionally large daily doses of vitamin<br />

D would rarely be recommended to patients. Researchers have<br />

noted that raising 25(OH)D from 20 ng/mL to the more optimal<br />

30+ ng/mL range in otherwise healthy patients would require<br />

ongoing daily supplementation of only about 1300 IU 39 to 1700<br />

IU 119 of vitamin D 3 . However, it should be noted that the daily<br />

adequate intake of vitamin D for maintaining health is, in most<br />

cases, lower than the amount needed as therapy for patients<br />

with chronic pain.<br />

Putting “D” Into Clinical Practice. In patients with pain,<br />

researchers have examined daily vitamin D supplementation<br />

ranging from 600 IU to 50,000 IU, 19,27,116 as well as much larger<br />

amounts. Because vitamin D has a long half-life and can take<br />

several months to reach steady-state levels, one approach to<br />

supplementation has been to administer oral or intramuscular<br />

megadoses on an infrequent basis. <strong>For</strong> example, single doses of<br />

300,000 IU D 2 have been used in the expectation that they might<br />

suffice for many months. 120 Hathcock et al 121 and others 122 noted<br />

that amounts of vitamin D up to 100,000 IU would not be toxic<br />

if restricted to one administration every four months, or daily<br />

for a single period of four days.<br />

In one study of patients with chronic back pain, subjects were<br />

treated for 3 months with either 5000 IU/day or 10,000 IU/day<br />

of vitamin D 3 (heavier patients >50 kg received the larger<br />

dose), 74 There were no adverse effects reported, and pain<br />

symptoms were relieved in 95% of the patients.<br />

Despite the reported successes of larger-dose vitamin D<br />

supplementation, many healthcare providers may be uncomfortable<br />

with recommending such doses for their patients. And,<br />

TABLE 4. Recommended <strong>Vitamin</strong> D Intake in<br />

Healthy Persons<br />

1997 — Institute of Medicine<br />

200 IU/d – children and adults to age 50 years<br />

400 IU/d – men and women aged 50-70 years<br />

600 IU/d – those older than 70 years<br />

2005 — Dietary Guidelines for Americans<br />

1000 IU/d – children and adults<br />

Note: In some of the literature International Units are expressed<br />

as micrograms. The conversion formula is 1 IU = 0.025 mcg or<br />

1 mcg = 40 IU.<br />

unless pathways of vitamin D metabolism are impeded (eg, due<br />

to liver or renal disease or an interacting drug), such high doses<br />

could be unnecessary, at least as initial therapy.<br />

In patients with chronic pain, Gloth and colleagues 79 observed<br />

that symptom relief often can be achieved with relatively modest<br />

increases in 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH) 2 D concentrations. This is<br />

possibly because the vitamin D metabolites are being rapidly<br />

consumed at tissue sites and also becoming depleted in storage<br />

depots, so they cannot accumulate in needed quantities and so<br />

any added amount is beneficial. These researchers also<br />

suggested that pain syndromes may affect vitamin D receptors,<br />

causing them to become altered in function or increased in<br />

quantity (upregulated) and, thereby, physiologically requiring<br />

extra amounts of the 1,25(OH) 2 D hormone.<br />

A proposed conservative dosing protocol is outlined in Table<br />

5. This involves adding a daily supplement of 2000 IU of vitamin<br />

D 3 to a daily multivitamin regimen, bringing the total daily<br />

vitamin D 3 intake to 2400 IU to 2800 IU. This is a convenient<br />

supplement dose, since inexpensive 1000 IU D 3 tablets or<br />

capsules are readily available and some outlets are now stocking<br />

2000 IU/dose tablets. The daily cost of the supplement is<br />

typically US $ 0.10 or less.<br />

<strong>Vitamin</strong> D 3 products are preferred since they cost no more<br />

than D 2 and most research indicates that D 3 is more effective<br />

19,115,118,123 Vieth 19 has strongly urged that “all use of vitamin D<br />

for nutritional and clinical purposes should specify cholecalciferol,<br />

vitamin D 3 .”<br />

<strong>Vitamin</strong> D therapy would be contraindicated in patients with<br />

pre-existing excessive levels of calcium (hypercalcemia or hypercalcuria),<br />

and special caution might be advised in those prone<br />

to forming kidney stones or other calcifications. 12,13,121 Besides<br />

renal or hepatic dysfunction, intestinal malabsorption due to<br />

age, irritable bowel syndrome, Crohn’s disease, or celiac disease<br />

also may limit response to vitamin D therapy. 20,51,124<br />

Current therapies for chronic pain, started prior to initiating<br />

vitamin D 3 therapy, do not need to be discontinued; however,<br />

it must be accepted that it could be difficult to attribute improvements<br />

to one therapy over another. This would be confounded<br />

further if new therapies for pain are started during vitamin D 3<br />

supplementation and before enough time has elapsed to evaluate<br />

its effectiveness.<br />

If there are no improvements after several months of the<br />

proposed conservative vitamin D 3 dosing protocol, more time<br />

rather than increased doses may be necessary for vitamin D 3<br />

Practical PAIN MANAGEMENT, July/August 2008<br />

©2008 PPM Communications, Inc. Reprinted with permission.<br />

33

<strong>Vitamin</strong> D for <strong>Chronic</strong> <strong>Pain</strong><br />

TABLE 5. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D Supplementation for<br />

<strong>Chronic</strong> <strong>Pain</strong><br />

PROPOSED CONSERVATIVE DOSING PROTOCOL<br />

• In patients with chronic, nonspecific musculoskeletal<br />

pain and fatigue syndromes, it usually can be expected<br />

that vitamin D intake from combined sources is inadequate<br />

and concentrations of serum 25(OH)D are insufficient<br />

or deficient.<br />

• All patients should take a multivitamin to ensure at least<br />

minimal daily values of essential nutrients, including<br />

calcium and 400 IU to 800 IU of vitamin D.<br />

• Recommend a daily 2000 IU vitamin D 3 supplement,<br />

bringing total supplement intake to 2400 to 2800 IU/day<br />

(incl. from multivitamin). Extra calcium may not be necessary<br />

unless diet is insufficient and/or there are concerns<br />

about osteoporosis (e.g., in postmenopausal<br />

women or the elderly).<br />

• Monitor patient compliance and results for up to 3<br />

months. Other therapies for pain already in progress do<br />

not necessarily need to be discontinued.<br />

• If results are still lacking after 3 months, or persistent<br />

25(OH)D deficiency or osteomalacia are verified, consider<br />

a brief course of prescribed high-dose vitamin D 3<br />

with, or without, added calcium as appropriate, followed<br />

by ongoing supplementation as maintenance.<br />

therapy to effectively raise 25(OH)D concentrations, lower PTH<br />

levels, and/or saturate vitamin D receptors with the 1,25(OH) 2 D<br />

metabolite. In some cases, the patient might benefit from a<br />

course of high-dose vitamin D 3 supplementation followed by<br />

more conservative doses for ongoing maintenance.<br />

There is always the possibility that a particular chronic pain<br />

condition cannot be alleviated by vitamin D 3 supplementation<br />

alone. <strong>For</strong> example, there may be a previously undetected<br />

anatomic defect, disease, or other pathology that would benefit<br />

from another type of therapeutic intervention in addition to<br />

vitamin D therapy.<br />

At the doses recommended in Table 5, excessive accumulation<br />

of 25(OH)D or toxicity over time would not be expected<br />

and this supplementation might be continued indefinitely. It<br />

must be noted, however, that clinical investigations have largely<br />

observed subjects during months rather than years of ongoing<br />

supplementation, and long-term effects of vitamin D therapy<br />

on functions at the cellular level are still under investigation. 30<br />

If there are concerns, after a year or longer the supplement<br />

might be continued at a reduced dose; it can always be increased<br />

again if pain symptoms return.<br />

How Long Until Improvement In anecdotal case reports,<br />

vitamin D supplementation provided complete relief within a<br />

week in some patients having widespread, nonspecific pain that<br />

was unresponsive to analgesics, including opioids. 79 In other<br />

cases, pain and muscle weakness reportedly resolved “within<br />

weeks” of beginning supplementation. 72<br />

In one study, pain relief from neuralgia was achieved at 3<br />

months after beginning vitamin D supplementation. 91 In many<br />

cases, bone-related pain may require approximately 3 months<br />

of adequate vitamin D supplementation for its relief, 47,65 while<br />

muscle pain may need 6 months, and muscle weakness or fatigue<br />

may require even longer to resolve. 47,65,76<br />

Overall, Vasquez and colleagues 37 recommended that at least<br />

5 to 9 months should be allowed for fully assessing either the<br />

benefits or ineffectiveness of vitamin D supplementation.<br />

Likewise, Vieth et al 100 suggested that the greatest physiologic<br />

responses may occur after 6 months of supplementation. Therefore,<br />

the timeframe recommended in Table 5 – monitoring<br />

results for up to 3 months – should be considered a minimum<br />

period of watchful waiting.<br />

Complete pain relief would be easy for patients to detect, but<br />

in most cases this could be an unrealistic expectation. The<br />

evidence is suggestive of a potential range of improvements with<br />

vitamin D therapy, some more obvious than others. <strong>For</strong> example,<br />

instead of complete pain relief, patients may experience partial<br />

relief, reduced intensity or frequency of pain, less soreness or<br />

stiffness in muscles, increased stamina or strength, reductions<br />

in NSAID or opioid use, and/or improvements in mood or<br />

overall quality of life. These results are less spectacular than<br />

complete pain relief, but are still important and worthwhile<br />

outcomes to monitor.<br />

<strong>Vitamin</strong> D Safety Considerations<br />

The highly favorable safety profile of vitamin D is evidenced by<br />

its lack of significant adverse effects, even at relatively high<br />

doses, and the absence of harmful interactions with other drugs.<br />

While vitamin D is potentially toxic, reports of associated<br />

overdoses and deaths have been relatively rare.<br />

Tolerance & Toxicity. Excessive intake and accumulation of<br />

vitamin D is sometimes referred to as “hypervitaminosis D,”<br />

however this is poorly defined. Because a primary role of vitamin<br />

D is facilitating absorption of calcium from the intestine, the<br />

main signs/symptoms of vitamin D toxicity result from excessive<br />

serum calcium, or hypercalcemia (see Table 6).<br />

The rather diverse signs/symptoms of hypercalcemia in<br />

patients with pain may be difficult to attribute to vitamin D<br />

intoxication, since they might mimic those of opioid side effects,<br />

neuropathy, or other conditions. Paradoxically, some symptoms<br />

match those of hypocalcemia. In some cases, patients with serum<br />

25(OH)D at toxic levels can be clinically asymptomatic. 126<br />

Since full exposure to sunlight can provide the vitamin D 3<br />

equivalent of up to 20,000 IU/day, the human body can obviously<br />

tolerate and safely manage relatively large daily doses. Toxicity<br />

has not been reported from repetitive daily exposure to sunlight. 25<br />

Still, supplementation via commercially manufactured<br />

vitamin D products would circumvent natural mechanisms in<br />

human skin that prevent excess D 3 production and accumulation<br />

resulting from sun exposure. A Tolerable Upper Intake<br />

Level, or UL, for oral vitamin D 3 supplementation—which is<br />

the long-term dose expected to pose no risk of observed adverse<br />

effects—currently is defined in the United States as 1000 IU/day<br />

in infants up to 12 months of age and 2000 IU/day for all other<br />

ages. 16 However, many experts assert that the 2000 IU/day UL<br />

is far too low. 19,35-37,39,42 An extensive review by Hathcock et al, 121<br />

applying risk-assessment techniques, concluded that the UL for<br />

vitamin D consumption by adults actually could be 10,000<br />

IU/day of D 3 , without risks of hypercalcemia.<br />

However, the duration of high vitamin D intake may be the<br />

34 Practical PAIN MANAGEMENT, July/August 2008<br />

©2008 PPM Communications, Inc. Reprinted with permission.

<strong>Vitamin</strong> D for <strong>Chronic</strong> <strong>Pain</strong><br />

more critical factor. Taking 10,000 IU of D 3 daily for six months<br />

has been implicated as toxic, 22,132 whereas Holick [2007] 14 noted<br />

that this daily amount in adults can be well tolerated for five<br />

months. And, this 10,000 IU/day dose was used successfully and<br />

safely during three months in one study for relieving back pain. 74<br />

Vieth et al 100 demonstrated that 4000 IU of D 3 per day was well<br />

tolerated during 15 months of therapy. Concentrations of<br />

25(OH)D were increased to more optimal levels and parathyroid<br />

hormone was reduced, while calcium levels remained normal.<br />

Some researchers have proposed that long-term daily<br />

consumption of 40,000 IU of vitamin D would be needed to<br />

cause hypercalcemia. 18,19 The US Office of Dietary Supplements<br />

133 notes that hypercalcemia can result from 50,000 IU/day<br />

or more taken for an extended period of time.<br />

There have not been any reports in the literature of a single,<br />

one-time excessive dose of vitamin D (D 2 or D 3 ) being toxic or<br />

fatal in humans. However, a number of incident reports of<br />

vitamin D toxicity involving very high doses, and including 6<br />

fatalities, have appeared in the literature. In the incident<br />

reports, encompassing 77 cases of toxicity, amounts of vitamin<br />

D taken for periods ranging from days to years included daily<br />

doses from 160,000 IU up to an astounding 2.6 million<br />

IU. 125,126,128,129,130,131,134,135 The relatively few fatalities resulted from<br />

secondary causes during treatment for hypercalcemia. A<br />

common feature of all incidents was that victims were not<br />

knowingly or intentionally taking excessive amounts of vitamin<br />

D, and no one was taking vitamin D under practitioner supervision.<br />

In almost all cases, toxic overdoses could have been<br />

avoided with better quality control in product manufacture<br />

and/or education of patients in the proper use of supplements.<br />

As another measure of safety, consolidated data for 2006 were<br />

examined (the most recently reported year) from 61 poison<br />

control centers serving 300 million persons in the United<br />

States. 136 There were only 516 mentions of incidents involving<br />

vitamin D which, by comparison, were roughly one-fourth the<br />

number for vitamin C and merely 0.8% of all incidents involving<br />

vitamin products. Only 13% of all vitamin D cases required<br />

treatment in a healthcare facility, although adverse<br />

signs/symptoms were absent or minimal in almost all patients<br />

(92%). Only 5 of the victims had more pronounced<br />

signs/symptoms of vitamin D toxicity, but these were not life<br />

threatening and there were no serious adverse events reported.<br />

<strong>Vitamin</strong> D-Drug Interactions<br />

There have been relatively few mentions in the literature of<br />

vitamin D supplements interacting with other agents or medications,<br />

and these are summarized in Table 7. In most cases, the<br />

potency of vitamin D is reduced by the other drug and the<br />

vitamin dose can be increased to accommodate this. Conversely,<br />

very high doses of vitamin D should be avoided due to possible<br />

risks of hypercalcemia when taken with digitalis/digoxin or<br />

certain diuretics.<br />

Additionally, St. John’s wort, 27 excessive alcohol, 133 and tobacco<br />

smoking 138 have been reported to potentially reduce the effects<br />

of vitamin D. Mineral oil and stimulant laxatives decrease<br />

dietary calcium absorption and can influence hypocalcemia. 133<br />

Gastric bypass and other gastric or intestinal resection procedures<br />

have been associated with vitamin D insufficiency. 60,106<br />

It should be noted that not all patients would be affected by<br />

these interactions or effects, and vitamin D has not been noted<br />

TABLE 6. Signs/Symptoms of D Toxicity<br />

(Hypercalcemia)<br />

• abdominal pain<br />

• achy muscles/joints<br />

• anorexia<br />

• azotemia<br />

• calcifications<br />

• constipation<br />

• disorientation/confusion<br />

• fatigue/lethargy<br />

• fever/chills<br />

• GI upset<br />

• hypertension<br />

• muscle weakness<br />

• nausea<br />

• nervousness<br />

• polyuria<br />

• proteinuria<br />

• pruritus<br />

• excessive thirst<br />

• urinary casts<br />

• vomiting<br />

• weight loss<br />

References: Barrueto et al 125 ; Blank et al 126 ; Calcitriol 12 ; Carroll and<br />

Schade 127 ; Ergocalciferol 13 ; Johnson 20 ; Klontz and Acheson 128 ; Koutkia et<br />

al 129 ; Todd et al 130 ; Vieth et al 131<br />

to interfere harmfully with the actions of any medications.<br />

Therefore, none of the reported interactions or effects has been<br />

indicated in the literature as a contraindication for vitamin D<br />

supplementation.<br />

Conclusions<br />

Extensive clinical evidence and expert commentary supports the<br />

opinion that recommending adequate vitamin D intake for<br />

helping patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain and fatigue<br />

syndromes should be more widely recognized and acted upon.<br />

In many cases, contributing factors are nonspecific or undetermined.<br />

Even in cases where a specific etiology has been<br />

diagnosed, the potential for vitamin D deficit as a factor<br />

contributing to and/or prolonging the pain condition should<br />

not be ruled out.<br />

Further clinical research studies would be helpful. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D<br />

is not proposed as a “cure” for all chronic pain conditions or in<br />

all patients. Optimal clinical outcomes of vitamin D therapy<br />

might be best attained via multicomponent treatment plans<br />

addressing many facets of health and pain relief. Therefore,<br />

vitamin D is not suggested as a replacement for any other<br />

approaches to pain management.<br />

To start, a conservative total daily supplementation of 2400<br />

IU to 2800 IU of vitamin D 3 is proposed as potentially benefitting<br />

patients. Along with that, some patience is advised regarding<br />

expectations for improvements; it may require up to 9<br />

months before maximum effects are realized. In some cases,<br />

other factors or undetected conditions may be contributing to<br />

a chronic pain condition that vitamin D supplementation alone<br />

cannot ameliorate.<br />

In sum, for patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain and<br />

related symptoms, supplemental vitamin D has a highly favorable<br />

benefit to cost ratio, with minimal, if any, risks. In all likelihood,<br />

it would do no harm and probably could do much good.■<br />

Acknowledgments<br />

The author wishes to acknowledge and thank the following<br />

expert reviewers of the full research report for their helpful<br />

comments and assistance: Bruce Hollis, PhD; Michael F. Holick,<br />

MD, PhD; Seth I. Kaufman, MD; Lee A. Kral, PharmD, BCPS;<br />

Paul W. Lofholm, PharmD, FACA; N. Lee Smith, MD; James D.<br />

Toombs, MD; Winnie Dawson, RN, BSN, MA.<br />

Practical PAIN MANAGEMENT, July/August 2008<br />

©2008 PPM Communications, Inc. Reprinted with permission.<br />

39

<strong>Vitamin</strong> D for <strong>Chronic</strong> <strong>Pain</strong><br />

TABLE 7. Drugs Potentially Interacting with<br />

<strong>Vitamin</strong> D<br />

Potency of vitamin D is reduced. The vitamin dose<br />

can be increased to accommodate this.<br />

• antacids (aluminum- or magnesium-containing)<br />

• anticonvulsants (eg, carbamazepine)<br />

• antirejection meds (after <strong>org</strong>an transplant)<br />

• antiretrovirals(HIV/AIDS therapies)<br />

• barbiturates (eg, phenobarbital, phenytoin)<br />

• cholestyramine<br />

• colestipol<br />

• corticosteroids<br />

• glucocorticoids<br />

• hydroxychloroquine<br />

• rifampin<br />

Risk of hypercalcemia when taken concurrently. Very<br />

high doses of vitamin D should be avoided.<br />

• digitalis/digoxin<br />

• thiazide diuretics<br />

References: Bringhurst et al 137 ; Calcitriol 12 ; Ergocalciferol 13 ;<br />

Holick 14 ; Hollis et al 124 ; Marcus 15 ; Mascarenhas and Mobarhan 51 ;<br />

ODS 133 ; Turner et al 60<br />

Disclosure<br />

The author reports no involvement in the nutritional supplement<br />

industry or any other conflicts of interest. Covidien/<br />

Mallinckrodt, St. Louis, MO, as a sponsor of <strong>Pain</strong> <strong>Treatment</strong><br />

<strong>Topics</strong>, provided educational funding support for the research<br />

report on <strong>Vitamin</strong> D but had no role in its conception or development.<br />

The sponsor has no vested interests in the nutritional<br />

supplement industry and is not a manufacturer or distributor<br />

of vitamin products.<br />

Stewart B. Leavitt, MA, PhD, is the founding Publisher/Editor of <strong>Pain</strong><br />

<strong>Treatment</strong> <strong>Topics</strong> and has more than 25 years of experience in healthcare<br />

education and medical communications serving numerous government<br />

agencies and other <strong>org</strong>anizations. He was educated in biomedical<br />

communications at the University of Illinois at Chicago College of<br />

Medicine and then served as a Commissioned Officer in the US Public<br />

Health Service at the National Institutes of Health. He went on to earn<br />

Masters and Doctorate degrees specializing in health/medical research<br />

and education at Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois. He is a<br />

member of the American Academy of <strong>Pain</strong> Management and a founding<br />

member of the International Association for <strong>Pain</strong> & Chemical<br />

Dependency.<br />

References<br />

1. Mohr SB, Garland CF, Gorham ED, Garland FC. The association between ultraviolet<br />

B irradiance, vitamin D status and incidence rates of type 1 diabetes in 51<br />

regions worldwide. Diabetologia. Online publication ahead of print, June 12, 2008.<br />

2. Ng K, Meyerhardt JA, Wu K, et al. Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and<br />

survival in patients with colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008. 26(18):2984-2991.<br />

3. Giovannucci E, Liu Y, Hollis BW, Rimm EB. 25-hydroxyvitamin D and risk of<br />

myocardial infarction in men. Arch Int Med. 2008. 168(11):1174-1180.<br />

4. APF (American <strong>Pain</strong> Foundation). <strong>Pain</strong> facts: overview of American pain surveys.<br />

2007. Available online at: http://www.painfoundation.<strong>org</strong>/page.aspfile=Newsroom/<br />

<strong>Pain</strong>Surveys.htm. Accessed 2/25/08.<br />

5. Nachemson A, Waddell G, Norlund A. Epidemiology of neck and back pain. In:<br />

Nachemson A, Jonsson E (eds) Neck and Back <strong>Pain</strong>: the Scientific Evidence of<br />

Causes, Diagnosis, and <strong>Treatment</strong>. Phila, PA: Williams & Wilkins; 2000: 165-188.<br />

6. NPF (National <strong>Pain</strong> Foundation). Harris Interactive Survey on <strong>Pain</strong> in America, Dec<br />

2007. Released in 2008. Avail at: http://www.nationalpainfoundation.<strong>org</strong>/<br />

MyResearch/<strong>Pain</strong>Survey2008.asp. Accessed 2/25/08.<br />

7. Watkins EA, Wollan PC, Melton III J, Yawn PB. A population in pain: report from<br />

the Olmsted County Health Study. <strong>Pain</strong> Med. 2008. 9(2):166-174.<br />

8. Deyo RA. Diagnostic evaluation of LBP. Arch Intern Med. 2002. 162:1444-1448.<br />

9. Deyo RA, Weinstein JN. Low back pain. New Eng J Med. 2001. 344:363-370.<br />

10. Holick MF. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D for health and in chronic kidney disease. Semin Dial. 2005.<br />

18:266-275.<br />

11. Lau AH, How PP. The role of the pharmacist in the identification and management<br />

of secondary hyperparathyroidism. US Pharmacist. 2007(Jul):62-70. Avail at:<br />

http://www.uspharmacist.com/index.asppage=ce/105514/default.htm. Accessed<br />

2/15/08.<br />

12. Calcitriol. Merck Manual [online]. 2007. Avail at: http://www.merck.com/<br />

mmpe/lexicomp/calcitriol.html. Accessed 2/19/08.<br />

13. Ergocalciferol. Merck Manual [online]. 2007. Avail at: http://www.merck.com/<br />

mmpe/lexicomp/ergocalciferol.html. Accessed 2/19/08.<br />

14. Holick MF. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007. 357(3):266-281.<br />

15. Marcus R. Agents affecting calcification and bone turnover: calcium, phosphate,<br />

parathyroid hormine, vitamin D, calcitonin, and other compounds. Chap 61. In:<br />

Hardman JG, Limbird LE, eds. Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of<br />

Therapeutics. 9th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1995.<br />

16. ODS (Office of Dietary Supplements; US National Institutes of Health). Dietary<br />

Supplement Fact Sheet: <strong>Vitamin</strong> D. Updated Feb 19, 2008. Avail at: http://dietarysupplements.info.nih.gov/<br />

factsheets/vitamind.asp. Accessed 4/27/08<br />

17. Singh YN. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D. Part I: Are we getting enough US Pharm. 2004a. 10:66-72.<br />

Avail at: http://www.uspharmacist.com/index.aspshow=article&page=<br />

8_1352.htm. Accessed 4/29/08.<br />

18. Tavera-Mendoza LE, White JH. Cell defenses and the sunshine vitamin. Scientific<br />

American. Nov 2007. Avail at: http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm id=celldefenses-and-the-sunshine-vitamin.<br />

Accessed 3/1/08.<br />

19. Vieth R. The pharmacology of vitamin D, including fortification strategies.<br />

Chapter 61. In: Feldman D, Glorieux F, eds. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D. 2nd ed. Boston, MA: Elsevier<br />

Academic Press; 2005. Avail at: http://www.directms.<strong>org</strong>/pdf/VitDVieth/Vieth%20chapter<br />

%2061.pdf. Accessed 4/17/08.<br />

20. Johnson LE. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D. Merck Manual [online]. 2007. Avail at:<br />

http://www.merck.com/mmpe/<br />

sec01/ch004/ch004k.htmlqt=vitamin%20D&alt=sh#tb004_6. Accessed 2/19/08.<br />

21. Lips P. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D deficiency and secondary hyperparathyroidism in the elderly:<br />

consequences for bone loss and fractures and therapeutic implications. Endocrine<br />

Rev. 2001. 22(4):477-501.<br />

22. Reginster J-Y. The high prevalence of inadequate serum vitamin D levels and<br />

implications for bone health. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005. 21(4):579-585. Avail at:<br />

http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/504783_ print. Accessed 2/24/08.<br />

23. Holick MF, Biancuzzo RM, Chen TC, et al. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D2 is as effective as vitamin<br />

D3 in maintaining circulating concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D. J Clin<br />

Endocrinol Metab. 2008. 93(3):677-687.<br />

24. Vieth R. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D supplementation, 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations, and<br />

safety. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999. 69:842-856.<br />

25. Hollis BW. Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels indicative of vitamin D sufficiency:<br />

implications for establishing a new effective dietary intake recommendation<br />

for vitamin D. J Nutr. 2005. 135:317-322. Available by search at:<br />

http://jn.nutrition.<strong>org</strong>/search.dtl. Accessed 4/2/08.<br />

26. Vieth R, Chan P-CR, MacFarlane GD. Efficacy and safety of vitamin D3 intake<br />

exceeding the lowest observed adverse effect level. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001:73: 288-294.<br />

Avail at: http://www.ajcn.<strong>org</strong>/cgi/content/full/73/2/288.<br />

27. Shinchuk L, Holick MF. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D and rehabilitation: improving functional<br />

outcomes. Nutr Clin Prac. 2007. 22(3):297-304.<br />

28. Holick MF. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D: the underappreciated D-lightful hormone that is important<br />

for skeletal and cellular health. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2002b;9:87-98.<br />

29. Holick MF, Chen TC. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D deficiency: a worldwide problem and health<br />

consequences. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008. 87(suppl):1080S-1086S.<br />

30. Marshall TG. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D discovery outpaces FDA decision making. Bioessays.<br />

2008. 30(2):173-182.<br />

31. Walters MR. Newly identified actions of the vitamin D endocrine system. Endocrine<br />

Rev. 1992. 13(4):719-764.<br />

32. Kawaguchi Y, Kanamori M, Ishihara H, et al. The association of lumbar disc<br />

disease and vitamin-D receptor gene polymorphism. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002.<br />

84-A(11):2022-2028.<br />

33. Videman T, Gibbons LE, Battie MC, et al. The relative roles of intragenic<br />

polymorphisms of the vitamin D receptor gene in lumbar spine degeneration and<br />

bone density. Spine. 2001. 26(3):A1-A6.<br />

34. Grant WB. An estimate of premature cancer mortality in the U.S. due to inadequate<br />

doses of solar ultraviolet-B radiation. Cancer. 2002. 94:1867-1875.<br />

35. Holick MF. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D: a millenium perspective. J Cell Biochem. 2003a. 88:296-<br />

307.<br />

36. Holick MF. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D: photobiology, metabolism, mechanism of action, and clinical<br />

applications. In: Favus MJ, ed. Primer on the Metabolic Bone Diseases and<br />

40 Practical PAIN MANAGEMENT, July/August 2008<br />

©2008 PPM Communications, Inc. Reprinted with permission.

<strong>Vitamin</strong> D for <strong>Chronic</strong> <strong>Pain</strong><br />

Disorders of Mineral Metabolism. 5th ed. Washington,<br />

DC: American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.<br />

2003c:129-137.<br />

37. Vasquez A, Manso G, Cannell J. The clinical<br />

importance of vitamin D (cholecalciferol): a paradigm<br />

shirt with implications for all healthcare providers. Alternative<br />

Therapies. 2004. 10(5):28-36. Avail at:<br />

http://www.vitamindcouncil.com/PDFs/CME-clinicalImportanceVitD.pdf.<br />

Accessed 2/21/08.<br />

38. Heaney RP. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D: how much do we need, and<br />

how much is too much Osteoporosis Int. 2000.<br />

11:553-555.<br />

39. Heaney RP. Functional indices of vitamin D status<br />

and ramifications of vitamin D deficiency. Am J Clin<br />

Nutr. 2004. 80(suppl):1706S-1709S.<br />

40. Heaney RP, Dowell MS, Hale CA, Bendich A.<br />

Calcium absorption varies within the reference range<br />

for serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D. J Am Coll Nutr. 2003b.<br />

22(2):142-146.<br />

41. Reginster J-Y, Frederick I, Deroisy R, et al. Parathyroid<br />

hormone plasma concentrations in response to<br />

low 25-OH vitamin D levels increase with age in elderly<br />

women. Osteoporosis Int. 1998. 8:390-392.<br />

42. Heaney RP, Davies KM, Chen TC, Holick MF,<br />

Barger-Lux MJ. Human serum 25-hydroxycholecalciferol<br />

response to extended oral dosing with cholecalciferol.<br />

Am J Clin Nutr. 2003a. 77:204-210.<br />

43. Holick MF. Sunlight and vitamin D: both good for<br />

cardiovascular health [editorial]. J Gen Intern Med.<br />

2002a. 17:733-735.<br />

44. Holick MF. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D deficiency: what a pain it is.<br />

Mayo Clin Proc. 2003b. 78:1457-1459. Avail at:<br />

http://www.mayoclinicproceedings.com/inside.aspAI<br />

D=464&UID. Accessed 2/18/08.<br />

45. Hickey L, Gordon CM. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D deficiency: new<br />

perspectives on an old disease. Curr Opin Endocrinol<br />

Diabetes. 2004. 11:18-25.<br />

46. AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and<br />

Quality). Cranney A, Horsley T, O’Donnell S, et al.<br />

Effectiveness and safety of vitamin D in relation to bone<br />

health. Evidence report/technology assessment No.<br />

158 (prepared by the University of Ottawa Evidence-<br />

Based Practice Center [UO-EPC]). AHRQ publication<br />

07-E013; Aug 2007. Avail at: http://www.ahrq.gov/<br />

downloads/pub/evidence/pdf/vitamind/vitad.pdf.<br />

Accessed 3/31/08.<br />

47. Heath KM, Elovic EP. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D deficiency: implications<br />

in the rehabilitation setting. Am J Phys Med<br />

Rehabil. 2006. 85:916-923.<br />

48. Plotnikoff GA, Quigley JM. Prevalence of severe<br />

hypovitaminosis D in patients with persistent, nonspecific<br />

musculoskeletal pain. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003.<br />

78:1463-1470.<br />

49. Jacobs ET, Alberts DS, Foote JA, et al. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D<br />

insufficiency in southern Arizona. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008.<br />

87(3):608-613.<br />

50. Gostine ML, Davis FN. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D deficiencies in<br />

pain patients. Prac <strong>Pain</strong> Mgmt. 2006(July/Aug):16-19.<br />

51. Mascarenhas R, Mobarhan S. Hypovitaminosis D-<br />

induced pain. Nutrition Reviews. 2004. 62(9):354-359.<br />

52. Bhattoa HP, Bettembuk P, Ganacharya S. Prevalence<br />

and seasonal variation of hypovitaminosis D and<br />

its relationship to bone metabolism in community<br />

dwelling postmenopausal Hungarian women. Osteoporosis<br />

Int. 2004. 15:447-451.<br />

53. Hoogendijk VJG, Lips P, Dik MG, et al. Depression<br />

is associated with decreased 25-hydroxyvitamin D and<br />

increased parathyroid hormone in older adults. Arch<br />

Gen Psychiatry. 2008. 65(5):508-512.<br />

54. Lotfi A, Abdel-Nasser AM, Hamdy A, Omran AA,<br />

El-Rehany MA. Hypovitaminosis D in female patients<br />

with chronic low back pain. Clin Rheumatol. 2007.<br />

26:1895-1901.<br />

55. MacFarlane GD, Sackrison JL Jr, Body JJ, et al.<br />

Hypovitaminosis D in a normal, apparently healthy<br />

urban European population. J Steroid Biochem Mol<br />

Biol. 2004. 89-90(1-5):621-622.<br />

56. Nesby-O’Dell S, Scanlon KS, Cogswell ME, et al.<br />

Hypovitaminosis D prevalence and determinants<br />

among African American and white women of reproductive<br />

age: third National Health and Nutrition Examination<br />

Survey, 1988-1994. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002.<br />

76:187-192.<br />

57. Sullivan SS, Rosen CJ, Chen TC, Holick MF.<br />

Seasonal changes in serum 25(OH)D in adolescent<br />

girls in Maine [abstract]. J Bone Miner Res. 2003.<br />

18(suppl 2):S407. Abstract M470.<br />

58. Tangpricha V, Pearce EN, Chen TC, Holick MF.<br />

<strong>Vitamin</strong> D insufficiency among free-living healthy<br />

young adults. Am J Med. 2002. 112:659-662.<br />

59. Yew KS, DeMieri PJ. Disorders of bone mineral<br />

metabolism. Clin Fam Pract. 2002. 4:522–572.<br />

60. Turner MK, Hooten WM, Schmidt JE, et al. Prevalence<br />

and clinical correlates of vitamin D inadequacy<br />

among patients with chronic pain. <strong>Pain</strong> Med. 2008.<br />

online publication prior to print.<br />

61. Hooten WM, Turner MK, Schmidt JE. Prevalence<br />

and clinical correlates of vitamin D in adequacy among<br />

patients with chronic pain. American Society of<br />

Anesthesiologists 2007 annual meeting, San<br />

Francisco. Oct 13-17, 2007. Abstract A1380.<br />

62. Hicks GE, Shardell M, Miller RR, et al. Associations<br />

between vitamin D status and pain in older adults: the<br />

Invecchiare in Chianti Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008.<br />

56(5):785-791.<br />

63. Armstrong DJ, Meenagh GK, Bickle I, et al. <strong>Vitamin</strong><br />

D deficiency is associated with anxiety and depression<br />

in fibromyalgia [abstract]. Reported in: J Musculoskeletal<br />

<strong>Pain</strong>. 2007. 15(1):55.<br />

64. Kealing J. Study: Joint pain ebbs with vitamin D.<br />

San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, Dec 16, 2007<br />

– reported via LJWorld.com. Avail at: http://www2.lj<br />

world.com/news/2007/dec/16/study_joint_pain_ebbs_v<br />

itamin_d/. Accessed 5/2/08.<br />

65. de la Jara GDT, Pecoud A, Favrat B. Female<br />

asylum seekers with musculoskeletal pain: the importance<br />

of diagnosis and treatment of hypovitaminosis<br />

D. BMC Family Practice. 2006. 7(4). Avail at:<br />

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2296/7/4.<br />

Accessed 3/8/08<br />

66. Benson J, Wilson A, Stocks N, Moulding N.<br />

Muscle pain as an indicator of vitamin D deficiency in<br />

an urban Australian Aboriginal population. Med J<br />

Australia. 2006. 185(2)76-77. Avail at: http://www.mja.<br />

com.au/public/issues/185_02_170706/ben10209_fm.ht<br />

ml. Access checked 3/3/08<br />

67. Helliwell PS, Ibrahim GH, Karim Z, Sokoll K,<br />

Johnson H. Unexplained musculoskeletal pain in<br />

people of South Asian ethnic group referred to a<br />

rheumatology clinic – relationship to biochemical<br />

osteomalacia, persistence over time and response to<br />

treatment with calcium and vitamin D. Clin Exp<br />

Rheumatol. 2006. 24(4):424-427.<br />

68. Erkal MZ, Wilde J, Bilgin Y, et al. High prevalence<br />

of vitamin D deficiencies, secondary to hyper-parathyroidism<br />

and generalized bone pain in Turkish<br />

immigrants in Germany: identification of risk factors.<br />

Osteoporosis Int. 2006. 17(8):1133-1140.<br />

69. Macfarlane GJ, Palmer B, Roy D, et al. An excess<br />

of widespread pain among South Asians: are low<br />

levels of vitamin D implicated Ann Rheum Dis. 2005.<br />

64(8):1217-1219.<br />

70. Baker K, Zhang YQ, Goggins J, et al. Hypovitaminosis<br />

D and its association with muscle strength,<br />

pain and physical function in knee osteoarthritis (OA): a<br />

30-month longitudinal, observational study. American<br />

College of Rheumatology meeting; San Antonio, TX;<br />

Oct 16-21, 2004. Abstract 1755.<br />

71. Haque U, Regan MJ, Nanda S. et al. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D: are<br />

we ignoring an important marker in patients with<br />

chronic musculoskeletal symptoms American College<br />

of Rheumatology meeting; San Antonio, TX; Oct 16-<br />

21, 2004. Abstract 694.<br />

72. van der Heyden JJ, Verrips A, ter Laak HJ, et al.<br />

Hypovitaminosis D-related myopathy in immigrant<br />

teenagers. Neuropediatrics. 2004. 35(5):290-292.<br />

73. Block SR. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D deficiency is not associated<br />

with nonspecific musculoskeletal pain syndromes<br />

including fibromyalgia [letter]. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004.<br />

79:1585-1591. Avail at: http://www.mayoclinicproceedings.com/inside.aspAID=2257&UID.<br />

Access<br />

checked 3/12/08.<br />

74. Al Faraj S, Al Mutairi K. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D deficiency and<br />

chronic low back pain in Saudi Arabia. Spine 2003.<br />

28:177-179.<br />

75. Huisman AM, White KP, Algra A, et al. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D<br />

levels in women with systematic lupus erythematosus<br />

and fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2001. 28(11):2535-<br />

2539.<br />

76. Glerup H, Mikkelsen K, Poulsen L, et al. Hypovitaminosis<br />

D myopathy without biochemical signs of<br />

osteomalacic bone involvement. Calcif Tissue Int.<br />

2000b. 66:419-424.<br />

77. Prabhala A, Garg R, Dandona P. Severe myopathy<br />

associated with vitamin D deficiency in western New<br />

York. Arch Intern Med. 2000. 160(8):1199-1203.<br />

78. McAlindon TE, Felson DT, Zhang Y, et al. Relation<br />

of dietary intake and serum levels of vitamin D to<br />

progression of osteoarthritis of the knew among<br />

participants in the Framingham Study. Ann Int Med.<br />

1996. 125(5):353-359. Avail at:<br />

http://www.annals.<strong>org</strong>/cgi/ content/full/125/5/353. Accessed<br />

4/21/08<br />

79. Gloth FM 3rd, Lindsay JM, Zelesnick LB,<br />

Greenough WB 3rd. Can vitamin D deficiency produce<br />

an unusual pain syndrome Arch Intern Med. 1991.<br />

151:1662-1664.<br />

80. Boland R. Role of vitamin D in skeletal muscle<br />

function. Endocr Rev. 1986;7:434-438.<br />

81. Haddad JG, Walgate J, Min C, Hahn TJ. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D<br />

metabolite-binding proteins in human tissue. Biochem<br />

Biophys Acta. 1976;444:921-925.<br />

82. Schott G, Wills M. Muscle weakness in osteomalacia.<br />

Lancet. 1976;2:626-629.<br />

83. Simpson RU, Thomas GA, Arnold AJ. Identification<br />

of 1,25- dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptors and activities in<br />

muscle. J Biol Chem. 1985. 260:8882-8891.<br />

84. Pfeifer M, Begerow B, Minne HW, et al. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D<br />

status, trunk muscle strength, body sway, falls, and<br />

fractures among 237 postmenopausal women with<br />

osteoporosis. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2001.<br />

109:87-92.<br />

85. Bischoff HA, Stahelin HB, Dick W, et al. Effects of<br />

vitamin D and calcium supplementation on falls: a<br />

randomized controlled trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2003.<br />

18:343-351.<br />

86. Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Willett WC, Wong JB, et al.<br />

Fracture prevention with vitamin D supplementation: a<br />

meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA.<br />

2005. 293(18):2257-2264.<br />

87. Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Giovannucci E, Willett WC, et<br />

al. Estimation of optimum serum concentrations of 25-<br />

hydroxyvitamin D for multiple health outcomes. Am J<br />

Clin Nutr. 2006. 84:18-28.<br />

88. Dukas L, Bischoff HA, Lindpainter LS, et al.<br />

Alfacalcidol reduces the number of fallers in a community-dwelling<br />

elderly population with a minimum<br />

calcium intake of more than 500 mg daily. J Am Geriatr<br />

Soc. 2004. 52:230-236.<br />

89. Sambrook PN, Chen JS, March LM, et al. Serum<br />

parathyroid hormone predicts time to fall independent<br />

of vitamin D status in a frail elderly population. J Clin<br />

Endocrinol Metab. 2004. 89:1572-1576.<br />

90. Boxer RS, Dauser RA, Walsh SJ, et al. The association<br />

between vitamin D and inflammation with the 6-<br />

minute walk and frailty in patients with heart failure. J<br />

Am Geriatr Soc. 2008. 56:454-461.<br />

91. Lee P, Chen R. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D as an analgesic for<br />

patients with type 2 diabetes and neuropathic pain.<br />

Arch Intern Med. 2008. 168(7):771-772.<br />

92. D’Ambrosio D, Cippitelli M, Cocciolo MG, et al.<br />

Inhibition of IL-12 production by 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin<br />

D3. J Clin Invest. 1998. 101:252-262.<br />

93. Schleithoff SS, Zittermann A, Tenderich G, et al.<br />

<strong>Vitamin</strong> D supplementation improves cytokine profiles<br />

in patients with congestive heart failure: a double-blind<br />

randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr.<br />

2006. 83:754-759.<br />

94. Van den Berghe, Van Roosbroeck D, Vanhove P, et<br />

al. Bone turnover in prolonged critical illness: effect of<br />

Practical PAIN MANAGEMENT, July/August 2008<br />

©2008 PPM Communications, Inc. Reprinted with permission.<br />

41

<strong>Vitamin</strong> D for <strong>Chronic</strong> <strong>Pain</strong><br />

vitamin D. J Clin Endocr Metab. 2003. 88:4623-4632.<br />

95. Thys-Jacobs S. Alleviation of migraine with therapeutic<br />

vitamin D and calcium. Headache. 1994a.<br />

34(10)590-592.<br />

96. Thys-Jacobs S. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D and calcium in<br />

menstrual migraine. Headache. 1994b;34(9)544-546.<br />

97. Gloth FM 3rd, Alam W, Hollis B. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D vs<br />

broad spectrum phototherapy in the treatment of<br />

seasonal affective disorder. J Nutr Health Aging. 1999.<br />

3(1):5-7.<br />

98. Lansdowne AT, Provost SC. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D3 enhances<br />

mood in healthy subjects during winter. Psychopharmacology.<br />

1998. 135(4):319-323.<br />

99. Basaran S, Guzel R, Coskun-Benliday I, Guler-<br />

Uysal F. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D status: effects on quality of life in<br />

osteoporosis among Turkish women. Qaul Life Res.<br />

2007. 16(9):1491-1499.<br />

100. Vieth R, Kimball S, Hu A, Walfish PG. Randomized<br />

comparison of the effects of the vitamin D3<br />

adequate intake versus 100mcg (4000 IU) per day on<br />

biochemical responses and the wellbeing of patients.<br />

Nutrition J. 2004. 3:8. Avail at: http://www.nutritionj.<br />

com/content/pdf/1475-2891-3-8.pdf. Accessed<br />

5/14/08.<br />

101. Smith GR, Collinson PO, Kiely PD. Diagnosing<br />

hypovitaminosis D: serum measurements of calcium,<br />

phosphate, and alkaline phosphatase are unreliable,<br />

even in the presence of secondary hyper-parathyroidism.<br />

Rheumatol. 2005. 32(4):684-689.<br />

102. Nellen JFJB, Smulders YM, PH Jos Frissen, EH<br />

Slaats, J Silberbusch. Hypovitaminosis D in immigrant<br />

women: slow to be diagnosed. BMJ. 1996. 312:570-572.<br />

103. Peach H, Compston JE, Vedi S, Horton LWL.<br />

Value of plasma calcium, phosphate, and alkaline<br />

phosphate measurements in the diagnosis of histological<br />

osteomalacia. J Clin Pathol. 1982;35:625-630.<br />

Avail at: http://jcp.bmj.com/cgi/reprint/35/6/625.<br />

Accessed 3/7/08.<br />

104. Cooper MS, Gittoes NJL. Diagnosis and management<br />

of hypocalcemia. BMJ. 2008. 336:1298-1302.<br />

105. Fitzpatrick L. Hypocalcemia: Diagnosis and <strong>Treatment</strong><br />

– Chapter 7. 2002. Endotext.com. Avail at:<br />

http://www.endotext.<strong>org</strong>/parathyroid/parathyroid7/parat<br />

hyroid7.htm. Accessed 2/23/08.<br />

106. Lyman D. Undiagnosed vitamin D deficiency in<br />

the hospitalized patient. Am Fam Phys. 2005.<br />

71(2):299-304. Avail at: http://www.aafp.<strong>org</strong>/afp/<br />

20050115/299.pdf. Accessed 4/30/08.<br />

107. Skugor M, Milas M. Hypocalemia. 2004. Cleveland<br />

Clinic; Avail at: http://www.clevelandclinicmeded.<br />

com/. Accessed 2/23/08.<br />

108. Peacey SR. Routine biochemistry in suspected<br />

vitamin D deficiency. JR Soc Med. 2004. 97:322-325.<br />

Avail at: http://www.jrsm.<strong>org</strong>/cgi/reprint/97/7/322.<br />

Accessed 3/8/08.<br />

109. Zerwekh JE. Blood biomarkers of vitamin D<br />

status. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008. 87(suppl):1087S-1094S.<br />

110. Singh RJ. Are clinical laboratories prepared for<br />

accurate testing of 25-hydroxy vitamin D [letter]. Clin<br />

Chem. 2008. 54(1):221-223.<br />

111. Masood H, Narang AP, Bhat IA, Shah GN. Persistent<br />

limb pain and raised serum alkaline phosphatase<br />

the earliest markers to subclinical hypovitaminosis D in<br />

Kashmir [abstract]. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1989.<br />

33(4):259-261.<br />

112. Holick MF. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D deficiency as a contributor<br />

to multiple forms of chronic pain – reply II [letter].<br />

Mayo Clin Proc. 2004a;79:694-709. Avail at:<br />

http://www.mayoclinicproceedings.com/inside.aspAI<br />

D=2197&UID. Accessed 3/7/08.<br />

113. IOM (Institute of Medicine). Standing Committee<br />

on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes.<br />

Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium, Phosphorus,<br />

Magnesium, <strong>Vitamin</strong> D, and Fluoride. Washington, DC:<br />

National Academy Press. 1997. 71-145.<br />

114. DHHS (US Department of Health and Human<br />

Services and US Dept of Agriculture). Dietary Guidelines<br />

for Americans, 2005. 6th ed. Washington, DC:<br />

US Government Printing Office. 2005(Jan). Avail at:<br />

http://www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2005/docu<br />

ment/. Accessed 5/18/08.<br />

115. Armas LAG, Hollis BW, Heaney RP. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D2 is<br />

much less effective that vitamin D3 in humans. J Clin<br />

Endocrinol Metab. 2004. 89(11):5387-5391. Avail at:<br />

http://jcem.endojournals.<strong>org</strong>/cgi/reprint/89/11/5387.<br />

Accessed 4/23/08.<br />

116. Barger-Lux MJ, Heaney RP, Dowell S. Chen TC,<br />

Holick MF. <strong>Vitamin</strong> D and its major metabolites: serum<br />

levels after graded oral dosing in healthy men. Osteoporos<br />