the explorers journal - The Explorers Club

the explorers journal - The Explorers Club

the explorers journal - The Explorers Club

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

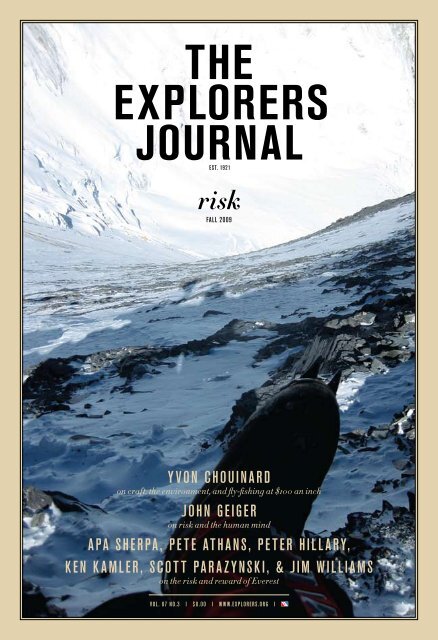

<strong>the</strong><br />

e x p lor e r s<br />

j o u r n a l<br />

EST. 1921<br />

risk<br />

fall 2009<br />

YVON CHOUINARD<br />

on craft, <strong>the</strong> environment, and fly-fishing at $100 an inch<br />

John Ge ige r<br />

on risk and <strong>the</strong> human mind<br />

Apa Sherpa, pete athans, Peter Hillary,<br />

Ken Kamler, Scott Parazynski, & Jim Williams<br />

on <strong>the</strong> risk and reward of Everest<br />

vol. 87 no.3 I $8.00 I www.<strong>explorers</strong>.org I

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong><br />

fall 2009<br />

cover: to <strong>the</strong> summit of Everest<br />

One step at a time. Photograph by<br />

Scott Parazynski.<br />

risk<br />

risk<br />

features<br />

On Risk<br />

by John Geiger, p. 12<br />

Bob Barth<br />

on life at <strong>the</strong> bottom of <strong>the</strong> sea, by Kristin Romey, p. 15<br />

Rich Wilson<br />

bringing high seas adventure into <strong>the</strong> classroom, p. 18<br />

Not a good day to die<br />

by Stephanie Jutta Schwabe, p. 21<br />

Art Mortvedt<br />

on grizzlies, engine-outs, and what it means to<br />

live <strong>the</strong> good life in <strong>the</strong> outback, p. 24<br />

Yvon Chouinard<br />

on craft, <strong>the</strong> environment, and fly-fishing at<br />

$100 an inch, p. 30<br />

R isk a nd Re wa r d<br />

of Everest<br />

in conversation with those who know <strong>the</strong><br />

mountain best, p. 34<br />

<strong>the</strong> West Buttress of Denali. Photograph by Matt Yamamoto.<br />

specials<br />

regulars<br />

Suicidal Birds<br />

fear, destiny, and <strong>the</strong> human mind, by<br />

Christopher Ondaatje, p. 48<br />

president’s letter, p. 2<br />

editor’s note, p. 4<br />

exploration news, p. 8<br />

extreme Medicine, p. 54<br />

A Risky Road to Freedom<br />

by Alan Nichols, p. 50<br />

extreme cuisine, p. 56<br />

reviews, p. 58<br />

what were <strong>the</strong>y thinking, p. 64

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong><br />

Fall 2009<br />

president’s letter<br />

Exploring <strong>the</strong> rewards of risk<br />

In this issue of <strong>The</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> Journal we explore <strong>the</strong> topics of risk<br />

and uncertainty from <strong>the</strong> explorer’s perspective. Although <strong>the</strong><br />

world has never been a certain place, uncertainty has become<br />

a prominent mainstay of today’s environment, where we are experiencing<br />

a multitude of rapidly and constantly shifting external<br />

variables, interacting in novel ways, which have proven extremely<br />

difficult to prophesy. Uncertainty pervades almost every aspect<br />

of <strong>the</strong> way <strong>the</strong> world business, educational, and o<strong>the</strong>r realms<br />

operate today. While such a volatile environment can, at times,<br />

seem threatening, <strong>the</strong> change it brings can also present fleeting<br />

windows of enormous opportunity. To steer clear of risk also<br />

means shunning <strong>the</strong> myriad opportunities that risk engenders.<br />

How do we best position ourselves to embrace <strong>the</strong> opportunities<br />

that such unpredictable change allows<br />

Embracing risk requires an understanding and acceptance of<br />

<strong>the</strong> challenges that accompany working in an uncertain environment.<br />

In order to take advantage of opportunities as <strong>the</strong>y present<br />

<strong>the</strong>mselves, <strong>the</strong> explorer must be as prepared as possible.<br />

To successfully ride out any hazards or peril, <strong>explorers</strong> must<br />

possess a diverse array of talents, an open mindset, flexibility,<br />

and <strong>the</strong> ability to adapt to new circumstances quickly. It is <strong>the</strong><br />

outstanding leaders who demonstrate <strong>the</strong>ir ability to master risk<br />

and uncertainty almost as a matter of routine. Despite being<br />

a difficult component to master, <strong>the</strong>re are ways to adapt and<br />

prevail, turning uncertainty into an advantage. <strong>The</strong> ability to<br />

embrace risk and uncertainty and channel <strong>the</strong>m into productive<br />

actions is what leads to discovery and innovation. Although <strong>the</strong><br />

uncertainties of such endeavors might be high, <strong>the</strong> rewards are<br />

potentially even greater, and <strong>the</strong> option of not doing anything,<br />

precluding new discoveries, represents <strong>the</strong> highest risk of all.<br />

galloping across <strong>the</strong> Tibet Plateau. Photograph by<br />

Robert Roe<strong>the</strong>nmund.<br />

Lorie Karnath, President

THE<br />

EXPLORERS CLUB TRAVELERS<br />

Unusual Luxury<br />

Adventures<br />

with Expert Leaders<br />

<strong>The</strong> Best of Indonesia<br />

Port Moresby to Manado<br />

February 15–March 6, 2010 (20 days)<br />

Manado to Bali<br />

March 2–18, 2010 (17 days)<br />

with Mike Messick (MN ‘96)<br />

Discover <strong>the</strong> diverse wildlife and<br />

cultures of Indonesia on two back-toback<br />

voyages aboard <strong>the</strong> luxurious 64-<br />

cabin expedition vessel Clipper Odyssey.<br />

FEATURED PROGRAMS<br />

“Without a doubt <strong>the</strong> best trip of our lives.”<br />

“<strong>The</strong> trip was truly a grand adventure.”<br />

“<strong>The</strong> trip offered excursions to places not<br />

accessible with o<strong>the</strong>r tours and cruises.”<br />

Voyage to Antarctica<br />

January 18–31, 2010 (14 days)<br />

with Kristin Larson (FN ‘02)<br />

See <strong>the</strong> amazing wildlife and landscapes of<br />

<strong>the</strong> "White Continent" during <strong>the</strong> beautiful<br />

Austral Summer. This extraordinary voyage<br />

combines spectacular natural wonders with<br />

an unparalleled level of comfort aboard <strong>the</strong><br />

all-suite, 57-cabin Corinthian II, equipped<br />

with an ice-streng<strong>the</strong>ned hull, Zodiacs, and<br />

stabilizer fins for smoo<strong>the</strong>r sailing.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Mighty Amazon<br />

April 4–20, 2010 (17 days)<br />

with Margaret Lowman (FN ‘97)<br />

Explore <strong>the</strong> heart of Amazonia on this remarkable,<br />

2,000-mile journey that encompasses virtually <strong>the</strong><br />

entire navigable length of <strong>the</strong> River, from <strong>the</strong><br />

Peruvian rainforest to its delta on <strong>the</strong> Atlantic<br />

Ocean, aboard <strong>the</strong> all-suite, 50-cabin Clelia II.<br />

For detailed information on <strong>the</strong>se and o<strong>the</strong>r journeys contact us at:<br />

800-856-8951<br />

Toll line: 603-756-4004 Fax: 603-756-2922<br />

Email: ect@studytours.org Website: www.<strong>explorers</strong>.org

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong><br />

Fall 2009<br />

editor’s note<br />

Risking it all for a better view<br />

You cannot stay on <strong>the</strong> summit forever,<br />

You have to come down again.<br />

So why bo<strong>the</strong>r in <strong>the</strong> first place<br />

Just this: what is above knows what is below,<br />

But what is below does not know what is above.<br />

One climbs, one sees. One descends.<br />

One sees no longer, but one has seen.<br />

—René Daumal<br />

Some years ago, when we were pulling toge<strong>the</strong>r an<br />

editorial tribute to <strong>the</strong> late Barry Bishop, a member of<br />

<strong>the</strong> first American expedition to summit Everest, his<br />

son Brent sent us this poem by René Daumal. For him,<br />

<strong>the</strong>se few lines summed up <strong>the</strong> “why” in why we climb,<br />

or, for that matter, engage in any endeavor that has a<br />

chance of providing us with a better, fuller perspective<br />

on <strong>the</strong> world we live in.<br />

In addressing <strong>the</strong> subject of risk this issue, we found<br />

it impossible to avoid discussing Everest, which, in<br />

recent years, has attracted its share of media attention<br />

for <strong>the</strong> deadly mishaps on <strong>the</strong> mountain—particularly<br />

in 1996 and in 2006. In discussing <strong>the</strong> risks posed<br />

by <strong>the</strong> world’s highest peak—first summited by our late<br />

Honorary President Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing<br />

Norgay in 1953—we have brought toge<strong>the</strong>r six Everest<br />

luminaries to share <strong>the</strong>ir stories and explain why, in<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir opinion, <strong>the</strong> reward outweighs <strong>the</strong> risk. <strong>The</strong>ir<br />

enlightened discussion begins on page 34.<br />

Beyond <strong>the</strong> Big E, we have looked in o<strong>the</strong>r risky<br />

endeavors—sailing <strong>the</strong> high seas, living on <strong>the</strong> ocean<br />

floor, and plying Arctic skies. We hope that in reading<br />

this issue, you will find yourself amply rewarded.<br />

Butter lamps burn in a Himalayan Monastery.<br />

Photograph by Scott Parazynski.<br />

Angela M.H. Schuster, Editor-in-Chief

letter to <strong>the</strong> editor<br />

In “A Day at <strong>the</strong> Beach” (<strong>The</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> Journal,<br />

Summer 2009), <strong>the</strong> author mentions first<br />

aid remedies for <strong>the</strong> box jellyfish of Australia<br />

and Indo-Pacific areas. He<br />

writes, “Vinegar should be<br />

applied to prevent fur<strong>the</strong>r<br />

nematocyst discharge, but<br />

pressure immobilization,<br />

administration of box jellyfish<br />

antivenin (obtained in<br />

Australia), and immediate<br />

evacuation are advised.”<br />

To my knowledge, <strong>the</strong><br />

pressure immobilization<br />

technique is no longer<br />

recommended to prevent<br />

absorption of box jellyfish<br />

venom. Some experts have<br />

questioned its efficacy and<br />

fur<strong>the</strong>r noted that large<br />

skin surfaces cannot be effectively<br />

bandaged. O<strong>the</strong>rs<br />

have noted that application of pressure might<br />

promote nematocyst discharge, which is believed<br />

to be more harmful than foregoing <strong>the</strong><br />

attempt to devascularize <strong>the</strong> area immediately<br />

below <strong>the</strong> bandage in order to <strong>the</strong>oretically<br />

prevent distribution of venom into <strong>the</strong> general<br />

circulation. Immobilizing (e.g., splinting)<br />

<strong>the</strong> stung body part would not be harmful,<br />

and might be helpful, but this is not proven.<br />

Recently, <strong>the</strong> efficacy of box jellyfish antivenin<br />

has been called into question, but <strong>the</strong>re have<br />

not yet been sufficient data and consensus<br />

from experts to provoke a change in current<br />

recommendations for its administration.<br />

<strong>The</strong> continued controversy about management<br />

of Indo-Pacific box jellyfish envenomation is<br />

highlighted and appreciated in <strong>the</strong> letter from<br />

Dr. Auerbach, a noted expert<br />

in marine envenomation.<br />

THE<br />

E X P L O R E R S<br />

JOURNAL<br />

EST. 1921<br />

destination moon<br />

SUMMER 2009<br />

BUZZ ALDRIN<br />

<br />

BILL “EART HRISE” A NDE RS<br />

<br />

P ETER DIAMANDIS<br />

<br />

VOL. 87 NO.2 I $8.00 I WWW.E X P LORE RS.ORG I<br />

While <strong>the</strong> issue about use of<br />

<strong>the</strong> pressure-immobilization<br />

technique may be evolving,<br />

as noted in <strong>the</strong> updated<br />

5th edition of Auerbach’s<br />

text, <strong>the</strong> indexed medical<br />

literature has only one report<br />

that suggests that this<br />

practice may be detrimental<br />

(Seymour J., et al., “<strong>The</strong> use<br />

of pressure immobilization<br />

bandages in <strong>the</strong> first aid<br />

management of cubozoan<br />

envenomings,” Toxicon<br />

40(10): 1503–5, 2002). In<br />

Australia, where carybdeid<br />

box jellyfish envenomation<br />

is a problem, topical application of vinegar<br />

remains <strong>the</strong> predominant first aid measure and<br />

uncertainty exists about <strong>the</strong> use of pressureimmobilization<br />

bandages (Barnett F.I., et<br />

al., Rural Remote Health 5(3): 369, 2005).<br />

O<strong>the</strong>rs also note that box jellyfish toxin is characterized<br />

but remains unidentified (Tibballs<br />

J., Toxicon 48(7): 830–59, 2006), current<br />

antivenin is not likely effective (Ramasamy S.,<br />

et al., Toxicon 41(6): 703–11, 2003), and that<br />

<strong>the</strong>re is a definitive need for uniform, evidencebased<br />

guidelines for management (Barnett F.I.,<br />

et al., Wilderness and Environmental Medicine<br />

15(2): 102–8, 2004).<br />

Paul S. Auerbach, M.D., FN’95<br />

Editor, Wilderness Medicine<br />

Author, Medicine for <strong>the</strong> Outdoors<br />

Consultant, Divers Alert Network<br />

Michael J. Manyak, M.D., FACS, MED’92,<br />

Professor of Urology, Engineering,<br />

Microbiology, and Tropical Medicine<br />

Editor, Expedition and Wilderness Medicine<br />

(2008).

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong><br />

fall 2009<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> club<br />

President<br />

Lorie M.L. Karnath,<br />

MBA, hon. Ph.D.<br />

Board Of Directors<br />

Officers<br />

PATRONS & SPONSORS<br />

Honorary President<br />

Don Walsh, Ph.D.<br />

Honor a ry Direc tors<br />

Robert D. Ballard, Ph.D.<br />

George F. Bass, Ph.D.<br />

Eugenie Clark, Ph.D.<br />

Sylvia A. Earle, Ph.D.<br />

James M. Fowler<br />

Col. John H. Glenn Jr., USMC (Ret.)<br />

Gilbert M. Grosvenor<br />

Donald C. Johanson, Ph.D.<br />

Richard E. Leakey, D.Sc.<br />

Roland R. Puton<br />

Johan Reinhard, Ph.D.<br />

George B. Schaller, Ph.D.<br />

Don Walsh, Ph.D.<br />

CLASS OF 2010<br />

Anne L. Doubilet<br />

William S. Harte<br />

Mark S. Kassner, CPA<br />

Daniel A. Kobal, Ph.D.<br />

R. Scott Winters, Ph.D.<br />

CLASS OF 2011<br />

Capt. Norman L. Baker<br />

Jonathan M. Conrad<br />

Constance Difede<br />

Kristin Larson, Esq.<br />

Margaret D. Lowman, Ph.D.<br />

CLASS OF 2012<br />

Josh Bernstein<br />

Lt.(N) Joseph G. Frey, C.D.<br />

Gary “Doc” Hermalyn, Ed.D.<br />

Lorie M.L. Karnath, MBA, hon. Ph.D.<br />

William F. Vartorella, Ph.D., C.B.C.<br />

Vice President, Chapters<br />

Lt.(N) Joseph G. Frey, C.D.<br />

Vice President, Membership<br />

Daniel A. Kobal, Ph.D.<br />

Vice President, Operations<br />

Garrett R. Bowden<br />

Vice President, Research & Education<br />

Julianne M. Chase, Ph.D.<br />

Treasurer<br />

Mark S. Kassner, CPA<br />

Assistant Treasurer<br />

William S. Harte<br />

Secretary<br />

Robert M.T. Jutson, Jr.<br />

Assistant Secretary<br />

Kristin Larson, Esq.<br />

Patrons Of Exploration<br />

Robert H. Rose<br />

Mr. & Mrs. Donald Segur<br />

Michael W. Thoresen<br />

Corporate Partner Of Exploration<br />

Rolex Watch U.S.A., Inc.<br />

Corporate Supporter Of Exploration<br />

National Geographic Society<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong><br />

EDITORS<br />

President & publisher<br />

Lorie M. L. Karnath,<br />

MBA, hon. Ph.D.<br />

Editor-in-Chief<br />

Angela M.H. Schuster<br />

Contributing Editors<br />

Jeff Blumenfeld<br />

Jim Clash<br />

Michael J. Manyak, M.D., FACS<br />

Milbry C. Polk<br />

Kristin Romey<br />

Carl G. Schuster<br />

Nick Smith<br />

Linda Frederick Yaffe<br />

Copy Chief<br />

Valerie Saint-Rossy<br />

ART DEPARTMENT<br />

Art Director<br />

Jesse Alexander<br />

Deus ex Machina<br />

Steve Burnett<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong> © (ISSN 0014-5025) is published<br />

quarterly for $29.95 by THE EXPLORERS CLUB, 46 East 70th<br />

Street, New York, NY 10021. Periodicals postage paid at<br />

New York, NY, and additional mailing offices. Postmaster:<br />

Send address changes to <strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>, 46 East<br />

70th Street, New York, NY 10021.<br />

Subscriptions<br />

One year, $29.95; two years, $54.95; three years, $74.95;<br />

single numbers, $8.00; foreign orders, add $8.00 per year.<br />

Members of THE EXPLORERS CLUB receive <strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong><br />

<strong>journal</strong> as a perquisite of membership. Subscriptions<br />

should be addressed to: Subscription Services, <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>, 46 East 70th Street, New York, NY<br />

10021.<br />

SUBMISSIONS<br />

Manuscripts, books for review, and advertising inquiries<br />

should be sent to <strong>the</strong> Editor, <strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>,<br />

46 East 70th Street, New York, NY 10021, telephone:<br />

212-628-8383, fax: 212-288-4449, e-mail: editor@<br />

<strong>explorers</strong>.org. All manuscripts are subject to review. <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong> is not responsible for unsolicited<br />

materials. <strong>The</strong> views and opinions expressed herein<br />

do not necessarily reflect those of THE EXPLORERS CLUB or<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>.<br />

All paper used to manufacture this magazine comes from<br />

well-managed sources. <strong>The</strong> printing of this magazine is FSC<br />

certified and uses vegetable-based inks.<br />

THE EXPLORERS CLUB, <strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> journaL, THE EXPLORERS<br />

CLUB TRAVELERS, WORLD CENTER FOR EXPLORATION, and <strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong> Flag and Seal are registered trademarks of<br />

THE EXPLORERS CLUB, INC., in <strong>the</strong> United States and elsewhere.<br />

All rights reserved. © <strong>The</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong>, 2009.<br />

50% RECYCLED PAPER<br />

MADE FROM 15%<br />

POST-CONSUMER WASTE

SAVE<br />

T H E<br />

DATE<br />

Thursday, October 15, 2009<br />

Cipriani Wall Street, New York City<br />

THE PRESIDENT, DIRECTORS AND<br />

OFFICERS OF THE EXPLORERS<br />

CLUB & ROLEX WATCH U.S.A.<br />

Request <strong>the</strong> honor of your company at <strong>the</strong> 2009<br />

Lowell Thomas Awards Dinner<br />

On <strong>the</strong> Brink of Uncertainty, Exploring Risk:<br />

A Survival Guide from <strong>the</strong> Field<br />

Photo: David Jordan www.lavajunkie.com<br />

2009 Lowell Thomas Award Recipients<br />

Bob Barth, CWO, USN (ret), FN’96<br />

Yvon Chouinard, MN’09<br />

Kenneth M. Kamler, M.D., FR’84<br />

Arthur D. Mortvedt, MN’84<br />

James M. Williams, FN’93<br />

Richard B. Wilson, MN’92<br />

Master of Ceremonies: Miles O’Brien<br />

Guest speakers include<br />

Dennis N.T. Perkins, MBA, Ph.D, author of<br />

Leading at <strong>the</strong> Edge, Leadership Lessons from Shackleton’s Antarctic Expedition<br />

Also featuring <strong>The</strong> Calder Quartet and Andrew WK<br />

performing a special composition for <strong>The</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong><br />

by Christine Southworth.<br />

Should you risk not attending Avoid this and reserve early. Tickets go on sale June 1, 2009. Seating for <strong>the</strong> dinner is on a first-come, first served basis. Seating<br />

requests require advance payment. For reservations, please visit www.<strong>explorers</strong>.org or contact <strong>The</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong>: 212-628-8383 or events@<strong>explorers</strong>.org

exploration news<br />

edited by Jeff Blumenfeld, www.expeditionnews.com<br />

Adventurer and aviator<br />

Bertrand Piccard recently<br />

unveiled <strong>the</strong> first prototype of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Solar Impulse aircraft HB-<br />

SIA at Dübendorf airfield just<br />

outside Zürich. A later model—<br />

<strong>the</strong> HB-SIB—will complete <strong>the</strong><br />

five-stage circumnavigation<br />

in 2012. Using nearly 12,000<br />

wing-mounted solar panels<br />

and four electric engines,<br />

power will be generated<br />

and stored in accumulators<br />

to allow <strong>the</strong> plane to fly in<br />

darkness—a breakthrough in<br />

aviation technology.<br />

<strong>The</strong> prototype aircraft that<br />

Piccard—along with fellow adventurer<br />

André Borschberg—<br />

will be night-flight testing is<br />

one of <strong>the</strong> most remarkable<br />

airplanes ever made. It has<br />

8<br />

Sol a r Impul se<br />

Unveiled<br />

Piccard’s sun-powered plane prepares for flight<br />

<strong>the</strong> wingspan of an Airbus<br />

340, but weighs less than a<br />

medium-size car (1,600 kg).<br />

According to aviation expert<br />

Dan Tye of Pilot magazine,<br />

“Nothing this big with such<br />

low weight has been built<br />

before.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> project has attracted<br />

several big name sponsors,<br />

including chemical and<br />

pharmaceutical multinational<br />

Solvay, Deutsche Bank, and<br />

watch manufacturer Omega,<br />

who provided <strong>the</strong> cockpit<br />

instrument panel, designed<br />

by Claude Nicollier, a former<br />

European Space Agency<br />

(ESA) astronaut. Omega<br />

also developed a simulation<br />

and testing system for <strong>the</strong><br />

airplane’s propulsion chain.<br />

For Piccard, <strong>the</strong> wider<br />

implications of Solar Impulse<br />

are symbolic. He sees solar<br />

technology as a force for environmental<br />

sustainability and<br />

he’s busy spreading <strong>the</strong> word.<br />

“We are convinced that a<br />

pioneering spirit and political<br />

vision can toge<strong>the</strong>r change<br />

society and put an end to fossil<br />

fuel dependency,” he says.<br />

Piccard and Borschberg have<br />

already taken models of Solar<br />

Impulse to China, India, and<br />

<strong>the</strong> UAE. Along <strong>the</strong> way, <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>explorers</strong> have been helped<br />

by high-profile ambassadors,<br />

including Prince Albert II of<br />

Monaco, Buzz Aldrin, Yann<br />

Arthus-Bertrand, Paulo<br />

Coelho, and Al Gore. For information<br />

about Solar Impulse<br />

and to follow its progress, visit<br />

www.solarimpulse.com.<br />

—Nick Smith<br />

K a t h m a n d u F i l m<br />

Festival<br />

documenting mountain environments<br />

<strong>The</strong> seventh Kathmandu<br />

International Mountain Film<br />

Festival will be held in <strong>the</strong><br />

Himalayan city this December<br />

10–14, 2009. <strong>The</strong> festival<br />

will screen some of <strong>the</strong> most<br />

recent and exciting films<br />

about mountains, mountain<br />

environments, and mountain<br />

cultures and communities.<br />

<strong>The</strong> KIMFF seeks to foster<br />

a better understanding of<br />

human experiences as well<br />

as of <strong>the</strong> social and cultural<br />

Photograph by Nick Smith.

ealities in <strong>the</strong> highlands of<br />

<strong>the</strong> world. For information:<br />

www.kimff.org.<br />

E v e r e s t s e a s o n<br />

highlights<br />

new records on <strong>the</strong> roof of <strong>the</strong> world<br />

Hahn hits record 11<br />

Rainier Mountaineering, Inc.<br />

(RMI) announced that on May<br />

23, at 6:00 a.m. local time,<br />

Dave Hahn and a RMI team of<br />

climbers summited Everest, an<br />

eleventh summit for <strong>the</strong> mountaineer<br />

and <strong>the</strong> most ascents<br />

by any non-Sherpa climber.<br />

Joining Dave were two accomplished<br />

RMI Guides, Melissa<br />

Arnot and Seth Waterfall,<br />

and cameraman Kent Harvey.<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r RMI Everest team,<br />

led by Peter Whittaker and<br />

EXPLORATION NEWS<br />

which included Ed Viesturs,<br />

Gerry Moffatt, Jake Norton,<br />

and John Griber, summited on<br />

May 19. Viesturs, FN’95, <strong>the</strong><br />

only American to summit all<br />

fourteen 8,000-meter peaks—<br />

doing so without bottled oxygen—reached<br />

<strong>the</strong> summit of<br />

Everest for his seventh time.<br />

To boldly Go<br />

American Scott Parazynski,<br />

FN’07, achieved a milestone<br />

on May 20, becoming <strong>the</strong> first<br />

astronaut to scale Everest.<br />

Parazynski, a veteran of<br />

five space shuttle missions,<br />

reached <strong>the</strong> summit at 4 a.m.<br />

local time and stayed on <strong>the</strong><br />

peak for about 30 minutes.<br />

He tried to summit Everest<br />

last year, but a slipped disc<br />

in his back foiled his plans.<br />

Parazynski’s trip wasn’t<br />

driven purely by <strong>the</strong> thirst for<br />

adventure. He also was on<br />

a science mission, setting<br />

up instruments “…looking<br />

for evidence of life in <strong>the</strong><br />

extreme…<strong>the</strong> kinds of things<br />

that once existed on Mars or<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r planets.”<br />

Apa Sherpa Nails 19<br />

Apa Sherpa re-established<br />

his image as <strong>the</strong> greatest<br />

living Everest summiteer,<br />

conquering <strong>the</strong> peak for a record<br />

nineteenth time at 8 a.m.<br />

local time on May 21. This<br />

year, he led <strong>the</strong> Eco-Everest<br />

Expedition 2009 to draw attention<br />

to <strong>the</strong> perils of climate<br />

change in <strong>the</strong> Himalayas.<br />

For more on Scott Parazynski and<br />

Apa Sherpa, see our “Risk and<br />

Reward of Everest” story, page 34.<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>

EXPLORATION NEWS<br />

In Amundsen’s<br />

footsteps<br />

South Pole centennial planned<br />

Liv Arnesen and Ann Bancroft<br />

will celebrate <strong>the</strong> 100th anniversary<br />

of Roald Amundsen’s<br />

reaching <strong>the</strong> South Pole with<br />

an international expedition<br />

scheduled to set off in October<br />

2011. An international team<br />

of six women—one from each<br />

continent—will embark on a<br />

1,400-kilometer (870-mile)<br />

expedition from <strong>the</strong> Bay of<br />

Whales in <strong>the</strong> Ross Sea to<br />

<strong>the</strong> Geographic South Pole.<br />

<strong>The</strong> collaboration between<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> and <strong>the</strong>ir native<br />

countries will provide a platform<br />

for millions of children<br />

around <strong>the</strong> globe to follow <strong>the</strong><br />

100-day expedition and learn<br />

that <strong>the</strong>y have a voice in <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

community and in <strong>the</strong> world<br />

to create positive change.<br />

Arnesen and Bancroft believe<br />

Antarctica, a continent<br />

of peace, cooperation, and<br />

science—owned by no one<br />

government—is <strong>the</strong> perfect<br />

place to stage such an expedition<br />

focused on making <strong>the</strong><br />

world a better place through<br />

collaboration and peaceful<br />

cooperation.<br />

<strong>The</strong> team will depart from<br />

Christchurch, New Zealand,<br />

in October, reach <strong>the</strong> South<br />

Pole by January 2012, and<br />

be flown to <strong>the</strong> coast. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

will <strong>the</strong>n travel back to New<br />

Zealand by air. For more information:<br />

Liv Arnesen, +47 901-<br />

37-030, liv@livarnesen.com;<br />

Ann Bancroft, 612-618-5533,<br />

ann@yourexpedition.com.<br />

In plane sight<br />

Fossett searchers seek lost aircraft<br />

Members of <strong>the</strong> Steve Fossett<br />

search team, Lew Toulmin,<br />

MN’04, and Robert Hyman,<br />

LF’93, have once again joined<br />

forces, this time as members<br />

of <strong>the</strong> private Missing Aircraft<br />

Search Team (MAST). <strong>The</strong> organization<br />

recently helped find<br />

Cessna 182 number N2700Q,<br />

missing since September<br />

2006. <strong>The</strong> Cessna, carrying<br />

pilot Bill Westover and passenger<br />

Marcy Randolph, took<br />

off from Deer Valley Airport in<br />

North Phoenix on September<br />

24, 2006, and headed north.<br />

It disappeared off radar nine<br />

nautical miles southwest of<br />

Sedona. Although a threeweek<br />

search by <strong>the</strong> Civil Air<br />

Patrol and o<strong>the</strong>rs came up<br />

empty, efforts by MAST and<br />

<strong>the</strong> family paid off. “We developed<br />

16 scenarios for <strong>the</strong><br />

possible plane crash, refined<br />

<strong>the</strong>m, and came up with three<br />

top candidate areas for <strong>the</strong><br />

location of <strong>the</strong> plane,” says<br />

Toulmin, an expert in emergency<br />

management. “<strong>The</strong><br />

plane was actually found in<br />

our highest probability area.”<br />

MAST members include<br />

experts in search <strong>the</strong>ory,<br />

search and rescue, aviation,<br />

aviation archaeology, radar<br />

analysis, emergency management,<br />

law enforcement, communications,<br />

mountaineering,<br />

expedition management, and<br />

wilderness survival.<br />

“As far as we know,” says<br />

Toulmin, “<strong>the</strong>re is no o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

group active in this area, trying<br />

to analyze cold cases of<br />

light aircraft disappearing,<br />

applying new technologies<br />

and methods, and <strong>the</strong>n capable<br />

of launching searches<br />

in high probability areas. We<br />

were motivated to do this in<br />

<strong>the</strong> Steve Fossett case, which<br />

is where we honed our skills.”<br />

For information: roberthy<br />

man@verizon.net.<br />

image courtesy Liv Arnesen and Ann Bancroft.<br />

10

SPECIAL REPORT<br />

Antarctica Update<br />

a treaty at 50 and o<strong>the</strong>r news<br />

by Kristin Larson, esq., FN’02<br />

This year marks an important<br />

milestone for <strong>the</strong> continent<br />

of Antarctica—<strong>the</strong> fiftieth anniversary<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Antarctic<br />

Treaty. Considering that at its<br />

conception, this treaty was<br />

viewed as both novel and not<br />

likely to survive, it has proven<br />

remarkably resilient, and is<br />

now revered as an exemplary<br />

international accord. This last<br />

point was emphasized by Secretary<br />

of State Hillary Clinton<br />

during her remarks at <strong>the</strong> recent<br />

Antarctic Treaty Consultative<br />

Meeting (ATCM) held in<br />

Washington, DC, stating that<br />

<strong>the</strong> treaty “is a blueprint for<br />

<strong>the</strong> kind of international cooperation<br />

that will be needed<br />

more and more to address <strong>the</strong><br />

challenges of <strong>the</strong> twenty-first<br />

century, and is an example of<br />

smart power at its best.”<br />

For <strong>the</strong> past five decades,<br />

<strong>the</strong> treaty has provided <strong>the</strong><br />

framework for human engagement<br />

on this remote icy continent,<br />

where science is <strong>the</strong> lingua<br />

franca and field research<br />

<strong>the</strong> basis for rapprochement.<br />

As <strong>the</strong> importance of <strong>the</strong> Polar<br />

Regions has grown, particularly<br />

as huge outdoor laboratories<br />

for understanding<br />

“whole Earth systems,” so has<br />

<strong>the</strong> complexity of <strong>the</strong> treaty.<br />

<strong>The</strong> number of treaty parties<br />

has grown from <strong>the</strong> original 12<br />

signatories to 47 nations, representing<br />

nearly 90 percent of<br />

all humankind.<br />

Clinton also addressed <strong>the</strong><br />

first joint meeting between<br />

<strong>the</strong> ATCM and its polar opposite,<br />

<strong>the</strong> Arctic Council, again<br />

characterizing <strong>the</strong> Antarctic<br />

Treaty as a “product of farsighted,<br />

visionary leaders…<br />

and a living example of how<br />

we can form a vital partnership.”<br />

Some commentators,<br />

less circumspect than Clinton,<br />

have expressed hope<br />

that <strong>the</strong> Antarctic Treaty will<br />

help inform <strong>the</strong> more pointed<br />

interactions now occurring in<br />

<strong>the</strong> increasingly accessible<br />

and politically strategic Far<br />

North.<br />

In recognition of <strong>the</strong> Antarctic<br />

Treaty anniversary, <strong>the</strong><br />

Smithsonian is hosting an<br />

“Antarctic Treaty Summit” in<br />

Washington, DC, November<br />

30–December 3, 2009, which<br />

will provide a unique international,<br />

interdisciplinary forum<br />

for scientists, legislators, lawyers,<br />

historians, students, and<br />

members of civil society to<br />

interact. For more information,<br />

see www.atsummit50.aq.<br />

<strong>The</strong> first “zero emissions”<br />

research station in Antarctica<br />

was inaugurated in February,<br />

putting Belgium back on<br />

<strong>the</strong> Antarctic map after an<br />

absence of 50 years. <strong>The</strong>ir<br />

new base, Princess Elizabeth<br />

Station, located in East Antarctica<br />

not far from <strong>the</strong> Droning<br />

Maud Land coastline,<br />

will generate its power from<br />

<strong>the</strong> 150-mile-per-hour winds<br />

experienced at this location<br />

and <strong>the</strong> 24 hours of sunlight<br />

during <strong>the</strong> austral summer<br />

months.<br />

Unfortunately, we recently<br />

lost two true Antarctic heroines.<br />

Edith “Jackie” Ronne,<br />

FN’91, was one of <strong>the</strong> two<br />

women to first winter-over in<br />

Antarctica during <strong>the</strong> Ronne<br />

Antarctic Research Expedition<br />

of 1946–48. Known as<br />

<strong>the</strong> “First Lady of Antarctica,”<br />

Jackie spent much of <strong>the</strong> past<br />

40 years educating <strong>the</strong> public<br />

about Antarctica, and made<br />

more than 15 trips south of<br />

70°. She was 89.<br />

Jerri Nielsen died a decade<br />

after her daring rescue<br />

from South Pole Station after<br />

diagnosing herself with breast<br />

cancer. She was able to carry<br />

out her duties as <strong>the</strong> winterover<br />

physician at this remotest<br />

spot on Earth with <strong>the</strong> assistance<br />

of airdropped chemo<strong>the</strong>rapy<br />

medications and <strong>the</strong><br />

intrepid non-medical wintering<br />

crew, who practiced for<br />

her biopsy using needles in a<br />

raw chicken.<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>

on<br />

Risk<br />

by John Geiger<br />

Many people are cautious, some to <strong>the</strong> point of<br />

cowardice, and, in <strong>the</strong> words of <strong>the</strong> actor Victor<br />

Mature, “wouldn’t walk up a wet step.” Caution,<br />

within reason, is only natural. As Kenneth Kamler<br />

wrote in Surviving <strong>the</strong> Extremes, “No animal in its<br />

right mind ever intentionally puts itself in danger by<br />

going somewhere it doesn’t belong.” Yet, as Kamler<br />

notes, human beings do go where <strong>the</strong>y don’t belong,<br />

for example, into <strong>the</strong> 8,000-meter (26,246)<br />

plus death zone of Mt. Everest. He suggests that<br />

human “emotional and spiritual imperatives” sometimes<br />

override <strong>the</strong> survival instinct. But in a recent<br />

article in <strong>the</strong> <strong>journal</strong> Neuron, British researchers<br />

also identified a neurological basis for people going<br />

where <strong>the</strong>y don’t belong. Human beings in <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

right mind do put <strong>the</strong>mselves in danger intentionally.<br />

Our brains, it turns out, reward risk.<br />

In an experiment carried out at <strong>the</strong> Wellcome<br />

Trust Centre for Neuroimaging at University<br />

College London, scientists found evidence that<br />

a primitive part of <strong>the</strong> brain has a role in making<br />

people adventurous, and is activated when people<br />

choose unfamiliar options, despite <strong>the</strong> inherent<br />

risks of <strong>the</strong> unknown. This suggests an evolutionary<br />

advantage for those who explore. Measuring<br />

blood flow in <strong>the</strong> brain, <strong>the</strong> researchers found that<br />

<strong>the</strong> ventral striatum, which is involved in processing<br />

rewards through <strong>the</strong> release of neurotransmitters<br />

like dopamine, is more active when subjects<br />

shunned <strong>the</strong> safer options to experience <strong>the</strong>

unusual. This is called <strong>the</strong> “novelty bonus.” Risk, it<br />

seems, is part of what it is to be human.<br />

That is not <strong>the</strong> only explanation for risk: <strong>The</strong> urge<br />

to explore is also <strong>the</strong> product of prosperous societies,<br />

like our own. In his groundbreaking study,<br />

<strong>The</strong> Human Brain in Space Time, about <strong>the</strong> psychology<br />

of space travel, <strong>the</strong> neurologist W. Grey<br />

Walter refuted <strong>the</strong> accepted historical wisdom<br />

that exploration—with all its inherent risks—was a<br />

response to economic and military necessity. To<br />

<strong>the</strong> contrary, he pointed out that, during great eras<br />

of exploration, expedition-sponsoring countries<br />

were often “hospitable, prosperous, and plagued<br />

only by familiar woes.”<br />

During <strong>the</strong> Edwardian era, Britain was more<br />

prosperous that at any o<strong>the</strong>r time in its history,<br />

and it gave rise to discovery, including <strong>the</strong> first<br />

South Pole explorations of Robert Falcon Scott<br />

and Sir Ernest Shackleton. <strong>The</strong> 1950s was one<br />

of <strong>the</strong> most prosperous eras in American history.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> United States, unprecedented numbers of<br />

families reached middle class status. It is also <strong>the</strong><br />

decade that gave birth to space exploration, and<br />

saw <strong>the</strong> British conquest of Mt. Everest.<br />

In developed countries, <strong>the</strong> subsequent six decades<br />

have been highly prosperous, <strong>the</strong> societies<br />

stable. Home has been a good place to be and, one<br />

would think, to stay. Yet those same comfortable,<br />

seemingly contented populations have produced<br />

large and growing numbers of people who have<br />

placed <strong>the</strong>mselves at great individual risk, engaging<br />

in exploration, extreme sports, and adventure travel.<br />

Voluntary risk has never been more pervasive.<br />

Two billionaires, tied at #261 on Forbes’s 2009<br />

list of <strong>the</strong> world’s wealthiest people, with fortunes<br />

of $2.5 billion each, embody this point. Virgin<br />

Companies founder Richard Branson and Cirque<br />

du Soleil founder Guy Laliberté can afford lives of<br />

great luxury and comfort, yet Branson has repeatedly<br />

risked his life and come close to dying in attempts<br />

to set distance records in hot air balloons.<br />

Laliberté, meanwhile, is scheduled to blast off on<br />

September 30 aboard a Soyuz spacecraft, becoming<br />

<strong>the</strong> seventh civilian to fly alongside astronauts<br />

and cosmonauts on <strong>the</strong> Russian spaceships.<br />

Risk-taking, it seems, is both part of our neurological<br />

makeup and an integral part of contemporary<br />

society. As Walter argued, “<strong>The</strong> urge to explore<br />

is a part of our nervous equipment…. <strong>The</strong> human<br />

species is unstable in stable environments.”<br />

<strong>The</strong>re certainly are emotional and spiritual<br />

14<br />

imperatives, as Kamler noted. Exploration is a way<br />

for people to gain insight not just into <strong>the</strong> world,<br />

but to better understand <strong>the</strong>mselves. Without risk<br />

<strong>the</strong>re is no gain, no gain in scientific knowledge,<br />

no gain ei<strong>the</strong>r in understanding one’s self.<br />

One of <strong>the</strong> most intriguing manifestations of<br />

risk is a subject I have been studying for six years.<br />

People at <strong>the</strong> very edge of death, often adventurers<br />

or <strong>explorers</strong>, have reported experiencing a<br />

sense of an incorporeal being who is beside <strong>the</strong>m<br />

and who encourages <strong>the</strong>m to make one final effort<br />

to survive. This phenomenon is known as <strong>the</strong><br />

“Third Man” factor, and it has been experienced<br />

by scores of people, from Shackleton and aviator<br />

Charles Lindbergh to polar explorer Ann Bancroft,<br />

climber Peter Hillary, diver Steffi Schwabe, and<br />

astronaut Jerry Linenger; in scores of places too,<br />

from Cape Horn to Carstensz Pyramid, from <strong>the</strong><br />

Indian Ocean to Earth’s orbit. Kamler, both a skilled<br />

medical specialist and climber, has had many remarkable<br />

adventures—he has devoted himself to<br />

<strong>the</strong> study of endurance, how our bodies respond<br />

to extremes—so it is not surprising that <strong>the</strong> “Third<br />

Man” phenomenon was also among <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

While desperately trying to keep a dying Sherpa<br />

alive through a long night high on <strong>the</strong> slopes of<br />

Everest, Kamler “gradually became aware of a third<br />

person in our freezing tent.” This unseen being guided<br />

Kamler through his patient’s treatment. “When<br />

morning came, I realized my patient would live, and<br />

that my mentor was gone.” It was, for Kamler, an<br />

experience filled with “wonder and mysticism,” and<br />

one that he would never have encountered by staying<br />

at his thriving medical practice in New York.<br />

Risk is innate to human beings, and so much<br />

a part of us that our brains dispense “novelty bonuses”<br />

to encourage us to take <strong>the</strong> more adventurous<br />

path. Risk is also powerfully influenced by <strong>the</strong><br />

great wealth and comfort enjoyed by those of us<br />

lucky enough to live in <strong>the</strong> West. We seek extreme<br />

and unusual environments to gain insight into <strong>the</strong><br />

nature of our planet, but also as a testing ground<br />

of <strong>the</strong> human spirit.<br />

biography<br />

John Geiger’s book, <strong>The</strong> Third Man Factor: Surviving<br />

<strong>the</strong> Impossible, was published on September 1, 2009, by<br />

Weinstein Books. He is Senior Fellow at Massey College<br />

and Fellow of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong>. For more information,<br />

visit www.thirdmanfactor.com.<br />

Opening spread: Whiteout on Mt. Rainier. Photograph by Steve Romeo.

RISK I<br />

Bob Barth<br />

on life at <strong>the</strong> bottom of <strong>the</strong> sea<br />

SeaLab Diver Bernie Campoli, as he appeared on <strong>the</strong> cover of <strong>the</strong> Saturday Evening Post, September 5, 1964. Photograph by Bob Barth<br />

Bob Barth has spent more time away from terra<br />

firma than most astronauts—and he’s never even<br />

left Earth. A pioneer in saturation diving, Barth has<br />

logged countless hours underwater as <strong>the</strong> world’s<br />

premier aquanaut, and is <strong>the</strong> only diver to have<br />

participated in <strong>the</strong> U.S. Navy’s groundbreaking<br />

Genesis (1957–1962), SeaLab I (1964), SeaLab<br />

II (1965), and SeaLab III (1969) programs.<br />

<strong>The</strong> son of an U.S. Army career officer, Barth<br />

was born in Manilla in 1930, joined <strong>the</strong> Navy at<br />

17, and, by 1960, he had already been a military<br />

diver for 11 years when he was stationed at <strong>the</strong><br />

Submarine Escape Training Tank at <strong>the</strong> Submarine<br />

School in Groton, CT, where he met Navy medical<br />

by Kristin Romey<br />

corps captain George Bond. At <strong>the</strong> time, <strong>the</strong> Navy<br />

was interested in developing techniques to extend<br />

<strong>the</strong> depth and duration of human underwater exploration<br />

through a technique known as saturation<br />

diving, and had put Bond in charge of a program<br />

known as Genesis.<br />

Saturation diving occurs when <strong>the</strong> partial pressure<br />

of dissolved inert gases in a human body<br />

equal <strong>the</strong> partial pressure of those in <strong>the</strong> ambient<br />

atmosphere—i.e., when <strong>the</strong> tissues of a diver’s<br />

body have absorbed all of <strong>the</strong> compressed gas<br />

(such as nitrogen or helium) <strong>the</strong>y can and become,<br />

literally, saturated. This generally occurs after diving<br />

for a very long duration or at great depth.<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>

While <strong>the</strong> concept of saturation diving was recognized<br />

as early as <strong>the</strong> beginning of <strong>the</strong> twentieth<br />

century, technical limitations at <strong>the</strong> time restricted<br />

divers to depths so shallow 50–100 feet (~15–30<br />

meters) that <strong>the</strong> applications of saturation diving<br />

were irrelevant. Decades later, however, as humankind<br />

began to push progressively deeper into<br />

<strong>the</strong> world’s oceans, conventional diving methods<br />

meant that a dive to 300 feet (~100 meters) or<br />

more could allow for only minutes of bottom time<br />

and subsequent hours of decompression—<strong>the</strong><br />

time required for <strong>the</strong> safe removal of <strong>the</strong> inert<br />

gas, such as nitrogen, inhaled under pressure.<br />

Extreme depth also led to <strong>the</strong> danger of nitrogen<br />

narcosis due to high levels of dissolved nitrogen in<br />

<strong>the</strong> blood, and even oxygen toxicity.<br />

What Bond realized was that a saturated diver<br />

could stay underwater for days or even months and<br />

<strong>the</strong> amount of time required for decompression<br />

wouldn’t change. <strong>The</strong> challenge, however, was<br />

how to avoid nitrogen narcosis and oxygen toxicity.<br />

Bond received permission from <strong>the</strong> Navy to study<br />

<strong>the</strong> effects of mixed-gas blends on mammals at<br />

<strong>the</strong> equivalent of 200fsw (feet of seawater). After<br />

evaluating <strong>the</strong> effects of helium-nitrogen-oxygen<br />

breathing mixes on goats and monkeys, he moved<br />

on to his human subjects, including Barth. “In a<br />

situation where you are an experimental diving<br />

subject in a new and unproven concept, you know<br />

<strong>the</strong> dangers (if <strong>the</strong>re are any) and are prepared for<br />

<strong>the</strong>m when <strong>the</strong>y occur—you knew that something<br />

new and different was just around <strong>the</strong> corner,<br />

and were expecting it,” says Barth, who remains<br />

unfazed by <strong>the</strong> days and weeks of pressurized<br />

experimental trials.<br />

With <strong>the</strong> successful completion of <strong>the</strong> program,<br />

<strong>the</strong> Navy, under Bond’s direction, began to<br />

study <strong>the</strong> practical applications of Genesis with<br />

SeaLab. Along with saturation diving, <strong>the</strong> SeaLab<br />

experimental habitat programs explored <strong>the</strong> physiological<br />

feasibility of living in isolated conditions<br />

underwater for long periods of time.<br />

In early 1964, <strong>the</strong> Navy commenced with <strong>the</strong><br />

building of SeaLab I in Panama City, FL, and on<br />

July 20th, <strong>the</strong> fire-engine-red habitat—constructed<br />

from two large floats—was lowered to a depth of<br />

193 feet (60 meters) off <strong>the</strong> Bermuda coast. Axles<br />

from railroad cars were among <strong>the</strong> thousands of<br />

pounds of weights that were placed in large ballast<br />

bins to anchor <strong>the</strong> structure once it was in place.<br />

Barth and his three colleagues—LCDR Robert<br />

Thompson, MC; GM1(DV) Lester Anderson,<br />

and HMC(DV) Sanders Manning—enjoyed a<br />

successful 11-day stay, performing physiological<br />

experiments while breathing a helium and oxygen<br />

mixture in an environment about equal to <strong>the</strong><br />

pressure of seven of Earth’s atmospheres. An approaching<br />

storm cut <strong>the</strong> planned 21-day project<br />

short; none<strong>the</strong>less, SeaLab 1 proved that man<br />

could survive—and thrive—in an open-sea saturation<br />

diving environment.<br />

In 1965, Barth was one of 28 men divided into<br />

three teams who would spend ano<strong>the</strong>r 15 days<br />

in <strong>the</strong> more ambitious SeaLab II program, in 205<br />

feet of water off <strong>the</strong> California coast. Bond’s team<br />

again looked at <strong>the</strong> issues of decompression<br />

sickness, inert gas narcosis, and oxygen toxicity,<br />

as well as body heat loss and carbon dioxide<br />

retention. “<strong>The</strong> gas mixtures in Genesis were<br />

somewhat <strong>the</strong> same mixtures that deep-sea divers<br />

had been using for years,” Barth recalls, “but what<br />

we needed to know was whe<strong>the</strong>r humans could<br />

breath that mixture at deeper depths and for much<br />

longer periods. Genesis and SeaLab provided<br />

that and a few hundred o<strong>the</strong>r answers—and <strong>the</strong><br />

food was lousy.”<br />

By <strong>the</strong> time SeaLab III was readied in 1969,<br />

Barth was designated team leader for <strong>the</strong> program.<br />

However, a leak occurred in <strong>the</strong> habitat, located in<br />

610 feet (185 meters) of water off California’s San<br />

Clemente Island, just before it was slated to be<br />

occupied. A four-man team, including Barth and<br />

diver Berry Cannon, descended in a diving bell<br />

to fix <strong>the</strong> leak; Cannon’s dive gear malfunctioned,<br />

which cost him his life.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Navy subsequently cancelled <strong>the</strong> SeaLab<br />

program, yet Barth has no regrets for his time<br />

spent participating in <strong>the</strong> ultimately ambitious, yet<br />

incredibly dangerous, line of undersea research.<br />

“When you enter into this kind of lifestyle, you<br />

know that someone, someday, somewhere, may<br />

not go home that night,” says Barth. “But I think<br />

that’s applicable to a lot of people who take on<br />

risks— it’s certainly not something that is seen only<br />

in <strong>the</strong> diving community.”<br />

“I have a good friend who once sat on <strong>the</strong><br />

pointed end of a big rocket and hung on when<br />

<strong>the</strong>y pushed <strong>the</strong> “GO” button. His organization is<br />

well known for taking chances and <strong>the</strong>y kept it up<br />

even with some terrible losses of life—think any of<br />

<strong>the</strong>m wanted to quit If we had a perfect world,”<br />

he adds, “it would soon grow stagnant, and no<br />

16

SeaLab III being towed out to sea off <strong>the</strong> coast of California, 1969. Image courtesy Bob Barth.<br />

one would seek new and rewarding goals.”<br />

Although Barth retired from active Navy duty<br />

in May 1970, <strong>the</strong> sea still beckoned. He went<br />

on to cofound <strong>the</strong> commercial dive company<br />

Hydrospace International before rejoining <strong>the</strong><br />

Navy Experimental Diving Unit in 1985, as a dive<br />

accident investigator and public affairs officer.<br />

SeaLab program and its aquanauts have been<br />

largely overshadowed by NASA’s Apollo program<br />

of <strong>the</strong> same decade, but its contributions, not only<br />

to <strong>the</strong> world of offshore oil and gas drilling, but<br />

also to underwater scientific research and submarine<br />

rescue, have been immeasurable.<br />

<strong>The</strong> first commercial saturation dive was conducted<br />

in 1965, and <strong>the</strong> extreme diving technique<br />

opened up a new world to <strong>the</strong> commercial oil and<br />

gas industry, allowing divers to construct rigs and<br />

infrastructure at depths never before accessible.<br />

Today, saturation divers in <strong>the</strong> North Sea regularly<br />

dive to depths of 750 feet (~230 meters) or more<br />

and remain underwater for months at a time.<br />

While remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and<br />

autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) are now<br />

replacing saturation divers for many tasks, <strong>the</strong>re<br />

are still many underwater jobs that require human<br />

dexterity, including pipeline repair and jobs requiring<br />

precise measurement.<br />

SeaLab’s legacy also lives on in <strong>the</strong> NOAA’s<br />

Aquarius habitat, <strong>the</strong> world’s only operating underwater<br />

research station, where scientists spend<br />

weeks at a time living and working at a depth of 20<br />

meters off <strong>the</strong> Florida Keys.<br />

Today Barth, <strong>the</strong> author of Sea Dwellers: <strong>The</strong><br />

Humor, Drama and Tragedy of <strong>the</strong> U.S. Navy<br />

SeaLab Programs (Doyle Publishing, 2000), still<br />

lives in <strong>the</strong> Panama City area.<br />

As for all of <strong>the</strong> dives Barth has made in his<br />

long, illustrious career, it was his first descent on<br />

SeaLab I that brings <strong>the</strong> biggest smile to his face. “I<br />

can tell you that those 11 days in that habitat were<br />

probably <strong>the</strong> best diving days I ever made,” recalls<br />

Barth. “Think about it, you travel down to 200 feet<br />

and not have to worry about bottom time, what you<br />

find sitting <strong>the</strong>re is this monster house, (not something<br />

that we see very often). Bright lights, fresh<br />

water, warm showers, bunks, and plenty to eat, and<br />

nobody with a damn stopwatch.”<br />

biography<br />

Kristin Romey, FR’05, is an underwater archaeologist and<br />

former executive editor of Archaeology magazine. She<br />

currently participates with <strong>the</strong> Universidad Autónoma de<br />

Yucatán’s Cenote Cult Project.<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>

RISK II<br />

Rich Wilson<br />

bringing high seas adventure<br />

into <strong>the</strong> classroom<br />

It has been called <strong>the</strong> most dangerous race in <strong>the</strong><br />

world. It is <strong>the</strong> Vendée Globe, a nonstop, single-handed,<br />

round-<strong>the</strong>-world voyage in which only <strong>the</strong> most seasoned<br />

sailors pilot <strong>the</strong>ir craft about <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn tips<br />

of Africa, <strong>the</strong> Americas, and Australia, all <strong>the</strong> while<br />

skirting <strong>the</strong> ice-choked waters of Antarctica. For most,<br />

simply completing <strong>the</strong> race is reward in itself. For Rich<br />

Wilson, <strong>the</strong> only American contender in a field of thirty<br />

in <strong>the</strong> 2008/09 race, completing <strong>the</strong> voyage on March 10<br />

after 121 days at sea had a higher purpose—to bring <strong>the</strong><br />

spirit of adventure into <strong>the</strong> classroom. <strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong><br />

<strong>journal</strong> recently spoke with Wilson about <strong>the</strong> legendary<br />

competition and his thoughts on inspiring <strong>the</strong> next<br />

generation.<br />

EJ: What led you to pursue a career in competitive<br />

sailing<br />

RW: Although I’ve sailed a lot, I don’t consider<br />

myself a professional sailor. I consider myself<br />

a professional educator. I grew up sailing and<br />

racing small boats, and worked my way up to<br />

18<br />

doing ocean races. In 1980, we won <strong>the</strong> Bermuda<br />

Race, which is <strong>the</strong> biggest offshore race in <strong>the</strong><br />

United States. That was simply a race for competition<br />

and fun, what I would call a recreational<br />

race. However, <strong>the</strong> three clipper route record<br />

passages—San Francisco to Boston by way of<br />

Cape Horn, doublehanded, 1993; New York<br />

to Melbourne by way of Cape of Good Hope,<br />

doublehanded, 2001; and Hong Kong–New<br />

York by way of Sunda Strait and Cape of Good<br />

Hope, doublehanded, 2003—plus <strong>the</strong> 2004<br />

solo Transatlantic Race and <strong>the</strong> 2008–2009<br />

Vendée Globe were all done to provide content<br />

for K—12 school programs through sitesALIVE!<br />

(www.sitesalive.com)<br />

During <strong>the</strong> Vendée Globe run, sitesALIVE<br />

had 50 U.S. newspapers publishing a 15-part<br />

weekly series written by me while I was at sea<br />

aboard Great American III. <strong>The</strong> newspapers<br />

<strong>the</strong>n distributed classroom sets of papers to<br />

participating teachers (whom <strong>the</strong> newspaper<br />

Rich wilson waves to <strong>the</strong> crowd upon completion of <strong>the</strong> 2008/09 Vendée Globe in Great American III, Images courtesy Rich Wilson.

around <strong>the</strong> world Nonstop<br />

Upon his completion of <strong>the</strong> 2008/09 Vendée Globe on March 10,<br />

Rich Wilson and <strong>the</strong> 60-foot Great American III had sailed 28,590.2 NM in<br />

121 days, 41 minutes, and 19 seconds.

had recruited by its marketing of our program, and<br />

whom had received our Teacher’s Guide with 15<br />

weekly classroom activities). We reached 7 million<br />

readers weekly and some 250,000 students<br />

with this program. Plus we had a team of more<br />

than a dozen experts—including Longitude author<br />

Dava Sobel; Jan Witting, a specialist in oceans<br />

and climate; and Ambrose Jearld of <strong>the</strong> National<br />

Marine Fisheries Service—who wrote for <strong>the</strong> series<br />

and answered students’ questions online.<br />

EJ: Sailing in <strong>the</strong>se races—with <strong>the</strong> wea<strong>the</strong>r and<br />

sea conditions and only one or two on board to<br />

handle <strong>the</strong> craft—is no mean feat. Have you had any<br />

particularly challenging or frightening moments<br />

RW: In 1990, during our first effort at <strong>the</strong> San<br />

Francisco-Boston race, we were capsized 400<br />

miles west of Cape Horn in 65-foot seas. We<br />

were upside down for 90 minutes before a wave<br />

re-righted <strong>the</strong> 60-foot-long, 40-foot-wide trimaran.<br />

This was <strong>the</strong> first time in history that a capsized<br />

trimaran has been re-righted by a wave.<br />

EJ: What was <strong>the</strong> first thing that went through your<br />

mind at that moment<br />

RW: Getting into <strong>the</strong> survival suit, setting off <strong>the</strong><br />

EPIRB [Emergency Position Indicating Radio<br />

Beacon], wondering how to make this dire situation<br />

better…<br />

EJ: How did you respond to <strong>the</strong> situation<br />

RW: Got into <strong>the</strong> survival suit, set off <strong>the</strong> EPIRB,<br />

cracked <strong>the</strong> emergency hatch to act as a pressure<br />

release valve for <strong>the</strong> compressing/decompressing<br />

of air in <strong>the</strong> cabin due to <strong>the</strong> waves surging<br />

into <strong>the</strong> cabin, sit on an upside down shelf to get<br />

out of <strong>the</strong> 40º F seawater.<br />

EJ: Had you prepared for such a situation<br />

RW: No. I had talked with several sailors who had<br />

been capsized in trimarans. And I had read about<br />

those situations. But <strong>the</strong>re was no information on<br />

a capsized trimaran being re-righted, because it<br />

had never happened. And, being back upright was<br />

worse. Upside down, we had shin-deep water in<br />

<strong>the</strong> cabin. Re-righted, we had neck-deep water in<br />

<strong>the</strong> cabin. So we moved flares, life raft, EPIRBS,<br />

etc., to <strong>the</strong> sail locker forward, and bailed out <strong>the</strong><br />

4 feet of water, and took refuge <strong>the</strong>re.<br />

EJ: Did <strong>the</strong> event change your approach to sailing<br />

RW: Not a lot. We had <strong>the</strong> gear that we needed<br />

close at hand. We’d picked a superstrong boat that<br />

survived <strong>the</strong> somersaulting double capsize. We’d<br />

try to do that again. Plus, we wouldn’t change how<br />

lucky we were to have <strong>the</strong> New Zealand Pacific<br />

[at <strong>the</strong> time, <strong>the</strong> world’s largest refrigerated container<br />

ship] find us, with a breathtakingly skilled<br />

and experienced crew aboard that executed an<br />

unimaginable rescue in appalling conditions.<br />

EJ: We know <strong>the</strong> risks inherent in what you do are<br />

formidable. What intellectual, spiritual, or emotional<br />

rewards you have garnered in <strong>the</strong> process<br />

RW: <strong>The</strong> sole reason to do <strong>the</strong>se most risky voyages<br />

has been to create programs ashore, primarily<br />

for schools, secondarily for asthmatics. I’ve had<br />

asthma since I was a one-year-old. For <strong>the</strong> Vendée<br />

Globe, our most recent race, we also added senior<br />

citizens to our program outreach as I was 58 at<br />

<strong>the</strong> start and thought <strong>the</strong>y would be able to relate.<br />

I’m a very conservative sailor, and risk management<br />

is accomplished by knowledge, experience,<br />

and preparation. I’m a professional educator, not<br />

a professional sailor, and I’ve raced <strong>the</strong> riskiest<br />

event in <strong>the</strong> world, <strong>the</strong> Vendée Globe. More than<br />

3,000 people have climbed Everest; 500 people<br />

have been astronauts; 50 have sailed solo nonstop<br />

around <strong>the</strong> world. Yet, I deem <strong>the</strong> potential benefits<br />

ashore for schoolchildren or asthmatics to be worth<br />

<strong>the</strong> personal risk to me offshore.<br />

EJ: Tell us about <strong>the</strong> impact of sitesALIVE.<br />

RW: SitesALIVE has produced 75 live, interactive,<br />

full-semester (12 weeks) programs for K–12 in <strong>the</strong><br />

past 16 years. <strong>The</strong>se have come from rainforest<br />

research centers, marine biology institutes, o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

sailing ships at sea, etc.; of <strong>the</strong> 75 programs, five<br />

have been my voyages. <strong>The</strong> concept is to excite<br />

and engage kids with <strong>the</strong> adventure, and if <strong>the</strong>y’re<br />

excited, <strong>the</strong>y pay attention, and if <strong>the</strong>y pay attention,<br />

<strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> science, math, geography flows freely and<br />

with purpose. It connects <strong>the</strong>m to real people doing<br />

real things in <strong>the</strong> real world.<br />

EJ: What advice would you have for someone following<br />

in your footsteps<br />

RW: Work your way up <strong>the</strong> knowledge and experience<br />

curve deliberately and slowly. Talk to those<br />

who know more than you do, read everything,<br />

prepare meticulously, ask questions, and, most<br />

important, listen to <strong>the</strong> answers.<br />

20

RISK III<br />

not<br />

a good day to die<br />

<strong>The</strong> Author makes her way through a grove of stalactites—several 100,000 years old—in <strong>the</strong> “Wedding Hall Room” within Lucayan Caverns, Grand Bahama, <strong>The</strong> Bahamas. Photograph courtesy Stephanie j. Schwabe.<br />

I can almost hear my black wetsuit and <strong>the</strong> 100<br />

pounds of metal equipment I have donned sizzle<br />

like a hot frying pan under a cold tap as I jump<br />

into <strong>the</strong> water. <strong>The</strong> sound is quickly downed out<br />

by <strong>the</strong> mass of air-bubbles exiting my dive-gear.<br />

If I had not jumped <strong>the</strong>n and <strong>the</strong>re into to <strong>the</strong> watery<br />

entrance of Guardian Cave—a fracture cave<br />

located on <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn end of <strong>the</strong> North Island of<br />

Andros—I would gladly have grabbed a knife and<br />

cut myself out of my suit. Removing <strong>the</strong> wetsuit<br />

in <strong>the</strong> conventional manner would have taken far<br />

too much time, rendering me unconscious with<br />

heatstroke from <strong>the</strong> high-noon Bahamian sun.<br />

I am not normally this stressed before a dive,<br />

but today I was working with a documentary film<br />

team from Japan. <strong>The</strong>re had been a lapse in translation<br />

of what was to happen before entering <strong>the</strong><br />

cave and I ended up standing in <strong>the</strong> sun with all<br />

my gear on for nearly 20 minutes as I waited for<br />

<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r two divers who were accompanying me<br />

into <strong>the</strong> cave to get into <strong>the</strong> water.<br />

As <strong>the</strong> cool water made its way into my wetsuit,<br />

my body responded quickly and I began to calm<br />

down, my heartbeat no longer audible to me. As I<br />

focused on my surroundings, I saw <strong>the</strong> two divers<br />

below me. <strong>The</strong>y seemed to be okay. I <strong>the</strong>n looked<br />

by Stephanie Jutta Schwabe<br />

for <strong>the</strong> down-line, which held our decompression<br />

gasses and extra bottles of compressed air. I<br />

saw <strong>the</strong> line in <strong>the</strong> shadow of <strong>the</strong> rock overhang<br />

above and swam over to it. I moved down <strong>the</strong> line,<br />

checking that each bottle was at <strong>the</strong> appropriate<br />

depth and that each was pressurized and ready<br />

for use in a moment’s notice. As I descended, <strong>the</strong><br />

water became darker and cooler, cool enough that<br />

I began to think, let’s just get on with <strong>the</strong> dive.<br />

I am not a cold-water diver by choice though<br />

most divers would not consider <strong>the</strong>se waters cold.<br />

However, I learned early on that, given enough<br />

time, any body of water that doesn’t match your<br />

body temperature can induce hypo<strong>the</strong>rmia. It may<br />

take longer for it to happen in <strong>the</strong>se waters but<br />

when you get out, your lips are purple and you<br />

shake like a leaf, begging for <strong>the</strong> sun’s embrace.<br />

As I finished checking <strong>the</strong> last bottle, I turned<br />

around to look for <strong>the</strong> two o<strong>the</strong>r divers, I spotted<br />

<strong>the</strong>m with <strong>the</strong>ir eyes glued on me. I signaled to<br />

<strong>the</strong>m to come over and when <strong>the</strong>y arrived, I began<br />

my decent to find <strong>the</strong> south leading guideline that<br />

had been placed in <strong>the</strong> cave earlier by o<strong>the</strong>r divers.<br />

I now hoped that <strong>the</strong> two divers would remember<br />

<strong>the</strong> plan we had discussed earlier and stick to it.<br />

I consider Guardian Cave a relatively simple<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>

cave to dive. <strong>The</strong> passage heads straight south,<br />

pinched out nearly 300 meters from <strong>the</strong> entrance.<br />

<strong>The</strong> exit, which was our entrance, progressed<br />

downward at a nearly 45º angle, demanding that<br />

divers constantly clear <strong>the</strong>ir ears. About 50 meters<br />

in, <strong>the</strong> passage opens up and <strong>the</strong> ceiling begins to<br />

cantilever away, enabling us to level out and swim<br />

without being forced to go deeper because of <strong>the</strong><br />

angle of <strong>the</strong> ceiling. It had its deep parts, 55 meters<br />

to <strong>the</strong> top of <strong>the</strong> sediment on <strong>the</strong> floor, but <strong>the</strong><br />

main passage was in shallower water so unless<br />

<strong>the</strong>re was a plan to collect floor sediments, as I<br />

had hoped, most of <strong>the</strong> dive would be in shallower<br />

water, making this a ra<strong>the</strong>r body-friendly dive.<br />

As we made our way in, I felt <strong>the</strong> heat of <strong>the</strong><br />

filming lamps on my backside. That was <strong>the</strong> signal<br />

for me to open up my plankton net and shine my<br />

dive light into it, making for more dramatic viewing.<br />

As I went deeper into <strong>the</strong> cave, <strong>the</strong> water—which<br />

near <strong>the</strong> entrance tends to be greenish brown<br />

because of organic input—became almost invisible.<br />

If it weren’t for <strong>the</strong> fact that I was floating and<br />

could feel <strong>the</strong> water, I wouldn’t know it was <strong>the</strong>re.<br />

It is breathtaking and always dramatic in its o<strong>the</strong>rworldly<br />

beauty. This is why I dive <strong>the</strong>se places.<br />

<strong>The</strong> walls, which seemed to continue endlessly<br />

above and below me, revealed beautiful curtain<br />

stalactites. Although <strong>the</strong>y were formed when sea<br />

level was some 200 meters lower, about 125,000<br />

years ago, <strong>the</strong>ir structures appear undisturbed<br />

by <strong>the</strong> change of events, sparkling in perfection<br />

except for <strong>the</strong> endless attack of bacterial acids.<br />

<strong>The</strong> entire wall is covered in holes nearly twocentimeters<br />

in diameter; even nature’s perfect<br />

crystal formations weren’t spared. This is what<br />

I was looking for—more evidence to support my<br />

biogenic hypo<strong>the</strong>sis that bacterial acids are responsible<br />

for dissolving <strong>the</strong> limestone and enlarging<br />

fracture caves, not rainwater acid, a <strong>the</strong>ory still<br />

being taught today. Excited by my find, I wanted<br />