contents - Hollins University

contents - Hollins University

contents - Hollins University

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Cargoes<br />

2009

Cargoes<br />

Quinquireme of Nineveh from distant Ophir<br />

Rowing home to haven in sunny Palestine,<br />

With a cargo of ivory,<br />

And apes and peacocks,<br />

Sandalwood, cedarwood, and sweet white wine.<br />

Stately Spanish galleon coming from Isthmus,<br />

Dipping through the Tropics by the palm-green shores,<br />

With a cargo of diamonds,<br />

Emeralds, amethysts,<br />

Topazes, and cinnamon, and gold moidores.<br />

Dirty British coaster with a salt-caked smoke stack<br />

Butting through the Channel in the mad March days,<br />

With a cargo of Tyne coal,<br />

Road-rail, pig-lead,<br />

Firewood, iron-ware, and cheap tin trays.<br />

John Masefield

Special thanks to<br />

Lisa Radcliff<br />

Brenda LaPrade<br />

Tony D‘Souza<br />

Claudia Emerson<br />

Richard Dillard<br />

TJ Anderson<br />

The Nancy Penn Holsenbeck Fund<br />

& the outstanding <strong>Hollins</strong> community that<br />

contributed to the creation of the 2009 issue of Cargoes.<br />

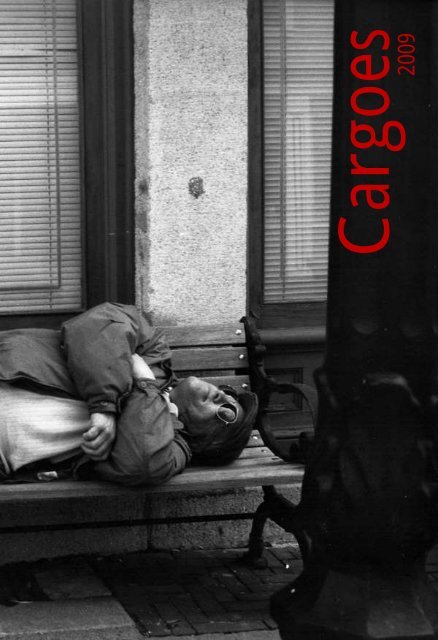

Front Cover<br />

Bum on Park Bench<br />

Catherine Stillerman<br />

Black and white photography<br />

Inside Covers<br />

Untitled<br />

Tiffany Robinette<br />

Oil, spraypaint, and collage on plexiglass

Cargoes 2009<br />

Editors<br />

Jeanette Jo Price<br />

Kathy Transue<br />

Readers<br />

Debbie Chow<br />

Amanda Gaye Smith<br />

Meaghan Quinn<br />

Kat Connor<br />

Jessica Franck<br />

Lilly Gray<br />

Taylor Hodge<br />

<strong>Hollins</strong> <strong>University</strong><br />

Roanoke, Virginia

Jessica Franck<br />

Meaghan Quinn<br />

Erin McKee<br />

Aaron Greenberg<br />

Debbie Chow<br />

Luke Johnson<br />

Kathy Transue<br />

Allison Hitt<br />

Amanda Mitchell<br />

Tallula Ho<br />

Amanda Gaye Smith<br />

Amy Dixon<br />

Anya Work<br />

Callie Bonatz<br />

Brittany Jamison<br />

Taylor Hodge<br />

Debbie Chow<br />

Renee Branum<br />

Kathy Transue<br />

Emily Campbell<br />

Erin McKee<br />

Amy Dixon<br />

Helen McKinney<br />

Jeanette Jo Price<br />

CONTENTS<br />

Poetry & Fiction<br />

A Scarlet House<br />

Letters, 1921<br />

Without Shoes On<br />

French French Burger<br />

a proper response to an old, white man who<br />

claims i shall know my place and write things<br />

asian-american<br />

THE HEART, LIKE A BOCCE BALL<br />

the debonair locals<br />

Cusco, Perú<br />

Route 7, Box 363<br />

Pattaya<br />

―Gentlemen‖ a found poem<br />

Saint Michael Lights a Candle<br />

The Reluctant Monk Ponders the Loss of His<br />

Hair By The Sea<br />

Experience<br />

1967<br />

Origin<br />

Stream of Mock Love\(Consciousness)<br />

Queenswalk, November<br />

Word Problem: Post-Colonial Theories<br />

Ladybug<br />

Avon Girls (excerpted from a longer work)<br />

Seven half diminished seven<br />

Praise For a Sick Woman<br />

Homme nu, homme noir<br />

6<br />

8<br />

9<br />

11<br />

16<br />

18<br />

19<br />

20<br />

21<br />

22<br />

24<br />

25<br />

26<br />

27<br />

29<br />

30<br />

32<br />

35<br />

36<br />

37<br />

39<br />

40<br />

42<br />

48

Catherine Stillerman<br />

Leigh Werrell<br />

Elizabeth Lawrence<br />

Catherine Stillerman<br />

Shazy Maldonado<br />

Kathy Transue<br />

Jeanette Jo Price<br />

Tess Waugh<br />

Kelly <strong>Hollins</strong><br />

Leigh Werrell<br />

Tiffany Robinette<br />

Tess Waugh<br />

Tess Waugh<br />

Kyra Orr<br />

Artwork<br />

Caroline<br />

That one‘s actually a man<br />

being comfortable with my feet<br />

Docks<br />

La Primogenita<br />

Okay, so this is how the universe works<br />

Le Coucher du Soleil sur le Sahara<br />

Mail Pouch<br />

Untitled<br />

Gesture<br />

Untitled<br />

Pure Gold<br />

When the fat lady sings...<br />

Untitled<br />

7<br />

10<br />

17<br />

23<br />

28<br />

31<br />

34<br />

38<br />

41<br />

47<br />

49<br />

50<br />

61<br />

62<br />

Fifth Annual National Undergraduate<br />

Poetry & Fiction Competition<br />

Liam Green<br />

Jessica Franck<br />

A Break From the Neighborhood<br />

From An Old Maid To Another<br />

52<br />

60<br />

Nancy Thorp High School Poetry Contest<br />

Allison Swagler<br />

Emily Swanagin<br />

Emily Swanagin<br />

Robin E. Burns<br />

Alexandra F. Brown<br />

Kelsey Greenwood<br />

Emma Roberts<br />

Eventually, it becomes too much<br />

Coordination<br />

Shema Yisrael<br />

―sensation‖<br />

Foiled<br />

Untitled<br />

What You‘re Not Telling Him<br />

64<br />

65<br />

66<br />

68<br />

70<br />

71<br />

72

A Scarlet House<br />

In a stark room<br />

I looked at projections<br />

of a scarlet house with<br />

four chambers and two chimneys<br />

It was precious<br />

the size of my fist<br />

velvet with warmth<br />

but I began to wonder<br />

how this delicate nature<br />

could keep going and<br />

How hadn‘t I noticed<br />

this exertion, that<br />

it was going to tire<br />

it was going to stop<br />

my life.<br />

A hand grasped my chest<br />

groping frantically against<br />

ribs bucking wildly<br />

breaching my body<br />

and nerves like hot wire<br />

squirming for an escape.<br />

When my fingertips<br />

heard a whisper<br />

of a chimneys‘<br />

rhythmic breath.<br />

Hushed, inside<br />

a scarlet house<br />

allaying my body<br />

by chambers rocking.<br />

Though,<br />

every so often<br />

a trembling hand<br />

slides off my collarbone<br />

and listens.<br />

Jessica Franck<br />

6

Caroline<br />

Catherine Stillerman<br />

Black and white photography

Letters, 1921<br />

I kept yr letters. the ones posted from Israel. in a hatbox on the mantle.<br />

You wrote on onion paper in black ink and quoted<br />

almanacs, the bible, Hitler, the stars.<br />

sometimes when I cannot sleep<br />

I read them out loud and wonder if<br />

sometimes, when you lie awake, you<br />

unfold my letters, envelopes balled in the coat pocket of yr frock<br />

slung over the back of a rocker. yr face bagged skin so plain in the den where<br />

you pick yr eyebrows and drink straight whiskey, hack, cough vanilla tar sucked<br />

out of a pipe. whiskey unwinding. stereo turned on low. cassette tape winding<br />

listening intently. soft copy of Anna Karenina read twice over on an arm chair.<br />

why.<br />

unblindfold yrself, glass owl eyes<br />

follow my umbrella out to the balcony. crow, a willet, straddles telephone wire.<br />

caw.<br />

have you shaven yr beard do the peonies still grow crooked against the white<br />

and black garage have you fixed the broken stove light Is there meaning in a<br />

word, in two bodies making love<br />

I‘ve been sleeping with yr letters, suckling the paper with my mouth<br />

open, palm open awaiting Eucharist, emptiness. yr translation of<br />

Catullus has bleached itself upon my tongue. why.<br />

an owl has been living in a tree near my house, you again. cuckoo.<br />

hammock halfmoon halfmoving in the wind, a cradle nesting in the owl‘s tree.<br />

museums, yr reflection hidden, blurred, color and water like a painting.<br />

the smell of paint contains me. You are pollution.<br />

plastic, crows, candles, genitals, clocks. why.<br />

Winter.<br />

we took the tram to Munich, yr eyes looked black from the moon. It started to<br />

snow.<br />

We spoke of the frost, art, the opera, yr wife. why.<br />

Meaghan Quinn<br />

8

Without Shoes On<br />

I.<br />

We're not in business to give away shoes, ma'am. But Ma'am is a revision--<br />

Mama's. The clerk-woman has on butterflied spectacles. Still works there, still<br />

wears them. And if I'd of had a peep hole, I'd of seen us reflected: Mama, rough<br />

pleats over her swelled-up belly, and Clinton there barefoot and folded in her<br />

skirts. But I can't see out. Naked and slick as a rabbit, stuck in a widow's gut. I<br />

can't see out, but they tell me about it—later.<br />

II.<br />

I'm telling you. I laid up for three months grieving that sonofabitch but I waited<br />

til Jim got born. Drank soda water and quit my insulin. No money. Let my feet<br />

fat up like grape-rot. Went on in the kitchen, and honey, the deeper that knife<br />

went the better I felt. See the scar, there— looks like rope burn but it ain't. Clinton—<br />

he's the one that ran for the ambulance. The oldest. Very smart. Course<br />

he's in a home now out in Garner. Owned by the same company as this one, can<br />

you believe it. Got him medicated so good he don't sit up straight. Let me tell<br />

you about that boy: He wasn't but six years old, walked down to the barber shop<br />

over yonder from the house and got him a haircut. Barber says that'll be two<br />

dollars. And what did that boy say He said just charge it to my account.<br />

Walked his little bare feet on out the door.<br />

III.<br />

Well, they got this dirty scab out back where the grass don't grow and they call it<br />

a courtyard. I said to someone this ain't much for a garden and they said what<br />

do you expect. Well. They call this place Martin House like the birds. Gourdliving<br />

birds, shit the ground white as April snow. Mama had a rack of them<br />

Martin gourds out back like to have drove us crazy. Maybe did. Noisy birds.<br />

And the smell. But the smell fits this place, now don't it. Got a younger brother<br />

comes twice a week and like to pass out. Works in an office in Raleigh, and<br />

does alright. You wouldn't know it, but Jim was born crooked, and without<br />

shoes on.<br />

Erin McKee<br />

9

That one’s actually a man<br />

Leigh Werrell<br />

Pen and ink

French French Burger<br />

William‘s voice makes a kind of high buzzing chirp. The sound your<br />

voice makes when you talk through an electric fan. He has not yet figured out<br />

how to clear his throat without tonsils. He comes out of the shower playing<br />

drums on his wet belly with plump little palms. He sings, ―Don‘t you wish your<br />

girlfriend was hot – like – meeee Don‘t you …Don‘t you‖ and then, ―I‘m<br />

gonna buy you a draaank, yeah eeyeah, ‗cause I got money in the baaank!‖<br />

William does not know what the words mean. He is seven. A little Italian<br />

Stallion. Slick hair, olive skin, macho swagger. Big brown heartbreakers<br />

framed in long lashes. The gold chain hung around his neck is sized to fit a<br />

grown man loosely. Saint Anthony rests just above his belly button.<br />

William has a clean, white scar that neatly bisects his scalp from ear to<br />

ear. He has an aide. A one-on-one. This skinny blonde high-schooler covered<br />

in freckles. She wears her hair in shoulder-length twin braids, like the girl on<br />

the Swiss Miss box. Her job is to stay with William all the time he is awake.<br />

William‘s first day at camp, I took the aide aside. I asked about the scar.<br />

―His skull was too small when he was born,‖ she told me. ―The doctors<br />

had to open it up and let it out a few inches so his brain would fit. At least, you<br />

know, for now.‖<br />

The way she said it made me think of a tailor altering a crotch. Because<br />

of his brain‘s short breath of fresh air, the aide explained, William is a little off.<br />

His thoughts jam up sometimes. He gets angry. The aide‘s job is mostly to deal<br />

with the freakouts and get him places on time.<br />

William goes over to the long green bench where his aide has left his<br />

backpack. He shoves his fist inside it and yanks out his pair of blue goggles like<br />

gutting a chicken. He brings them to the old sagging couch where I have been<br />

sitting, waiting for him to get out of the shower. The couch got left outside during<br />

the off season. We dragged it back into the pool house at the beginning of<br />

the summer. It smells like rotten pumpkins. I smooth William‘s hair and sling<br />

the band of his goggles over his head. He slaps the lenses into his eye sockets.<br />

He holds his hand up for me. I take it, and walk him poolside.<br />

William is my first lesson today. I hand him a bottle of sunscreen and<br />

he glops himself with white. The sun streams the dew off the soccer field beyond<br />

the pool house fence, and the woman I am in love with comes striding<br />

through the wet grass. Olena Anatolyevna Mokrenko: soft mass of rippled redbrown<br />

curls, like something you would drizzle on a cheesecake. Long, tanned<br />

legs crowned with two perfect muscular nerf balls of ass. Flashing warrior‘s<br />

eyes. Sly predator‘s smile. She calls me ―Malisch.‖ In her language it means,<br />

―little boy.‖ From her height, that is how I look. As she passes, on her way to<br />

her ropes course in the woods, I put my hand over my heart. I call out to her,<br />

―Ti oten kressiva ya!‖ In her language it means, ―You are beautiful!‖ I do this<br />

every morning. It is a ritual of ours. It is a win-win situation. I get to vent this<br />

boiling joy reaction that happens in my stomach when I see her. She gets to<br />

have the first sounds she hears each day be the birds singing, and children<br />

laughing, and someone telling her she is beautiful. We would have to stop, of<br />

course, if any of the campers knew Russian. Or maybe we would not. After all,<br />

11

what I say is not lewd, or in poor taste, or of a corrupting nature to the mind of a<br />

child. It is just a very loud, from-the-diaphragm statement of fact.<br />

I am teaching William to dive. I climb up onto the diving board and<br />

show him. Palms together. Arms out straight. Hug your ears with your elbows.<br />

Push off with your feet. Legs straight. Feet together. I dive. The world is gone<br />

for a few seconds. Everything is cool and blue and silent. I weigh nothing. I am<br />

everywhere embraced. The water loves me.<br />

I break the surface. Swim to the side. William claps. We start him on<br />

the side of the pool, not the diving board. He starts kneeling instead of standing<br />

so it is not such a long way down. So he is not so afraid. I watch him from the<br />

water. His first try, he skids off the surface like a panicked alligator. He swallows<br />

some water and coughs.<br />

―You okay, William‖ I know he is okay. If you‘re coughing, you‘re<br />

breathing. But I ask anyway.<br />

―Yeah,‖ he says, ―did I dive‖<br />

―No,‖ I say, ―but close.‖ I tell him what he needs to do. He needs to<br />

push off more, and think about going more down than out. He needs to pick a<br />

spot in the water, keep his eye on it, and push off with his feet until he is there.<br />

He swims to the side, and beaches himself on the wet concrete. He stands up<br />

and squeezes the water from the pockets of his trunks. He shakes his butt and<br />

sings, ―My milkshake brings all the boys to the yard!‖ His voice is like a cricket<br />

from Brooklyn. He kneels down and tries his dive again. He gets a little closer<br />

this time. Tries again. He needs to keep his legs together. Point his toes. This<br />

would be a lot easier if I could do what my father did. If I could put one hand<br />

around his waist, the other around his ankles, and guide him into the water.<br />

But this is America, and it is better not to touch if you can help it.<br />

―Did I dive‖<br />

―Not yet, William. Closer though. Let‘s try it standing up this time.‖<br />

He shrugs his shoulders. He claps his hands and rubs them together.<br />

He plants his feet, bends his knees, and springs up, arcs beautifully, brings his<br />

legs too far forward and flips over as he enters the water. He makes a long<br />

splash with his feet. It spatters the opposite side of the pool. It kills a bumblebee<br />

on the wing. I hear it slap the pavement. I hear its last feeble buzzes. William<br />

twists himself around and comes up for air.<br />

―Did I dive‖<br />

―Almost, William. Your splash killed a bee though.‖<br />

―Yes!‖<br />

―William, that‘s not nice.‖<br />

―Oh.‖<br />

―We should go over and say we‘re sorry.‖<br />

William nods solemnly, and we swim across to the other side of the<br />

pool. The bumblebee is still there, twitching a little in the puddle from William‘s<br />

splash. We climb out and squat down. William pokes the bee in the furry<br />

hind end with his pinky finger. The bee shudders. William grabs my shoulder<br />

and shakes me.<br />

―He ain‘t dead!‖<br />

―Don‘t touch it, William. I don‘t want you to get stung.‖<br />

The binder with the chlorine test log leans up against the fence. I slip a<br />

12

lank log report out, and slide the paper underneath the bee. Lift it off to a dry<br />

spot on the deck.<br />

―He gonna get better‖<br />

―Yeah, I think he just needs to sit out in the sun until his wings dry off.‖<br />

―Oh. Should we blow on him‖<br />

―No. I don‘t think we should. Let‘s just give him some time.‖<br />

We get back into the water and keep on with William‘s diving. He gets<br />

steadily better. His only problem now is not letting himself flip over. For this I<br />

say he needs to point his toes and get a good strong push that will propel him<br />

straight into the water. It is getting to feel like we have been in the pool for<br />

awhile. I cannot be sure, though. I have lost my watch. I am sad about this. It<br />

was a great watch, a waterproof Timex with a brown faux-leather band. It had<br />

hands and fancy-written numbers. It lit up green when you pressed the little<br />

silver stud on the side. I felt elegant wearing it. Thirty dollars I paid. At Wal-<br />

Mart. A deal. And it is gone now. Disappeared like so many things in my life.<br />

When I was little I can remember thinking to myself, ―You will be a great magician<br />

someday. Everything you touch disappears.‖ I look around for someone<br />

with a watch. The only people at the pool are me, William, and his aide. William<br />

is not wearing a watch.<br />

―William‖<br />

William has been trying to fit his head into the pool filter. He does not<br />

stop when I say his name. He says, ―Yeah‖<br />

―William, what‘s your lady‘s name‖<br />

―My what‖<br />

―Your aide. The lady who comes to camp with you.‖<br />

―Who‖<br />

I tap William on the shoulder and point over the side of the pool to<br />

where the aide sits, reading her paperback.<br />

―That lady, William. Can you tell me what her name is‖<br />

―Ummm…‖ his voice makes this keening buzz. The largest mosquito<br />

you have ever heard. He says ―um‖ for a very long time. Then he says, ―I<br />

dunno.‖<br />

―William,‖ I say, ―that lady is with you every second of the day. Are you<br />

sure you don‘t know what her name is‖<br />

―Umm… Jessica‖<br />

I hoist myself up onto the side of the pool and say ―Jessica‖ to the aide.<br />

The aide plays with her hair. She takes the end of one braid between<br />

her thumb and index fingers. She slips it into the corner of her mouth and begins<br />

to chew it and suck on it with great enthusiasm. She seems totally absorbed<br />

in this and in the paperback she reads. She does not answer when I call,<br />

so I call again.<br />

―Jessica.‖<br />

She wiggles her feet out of her sandals. The sandals are made of translucent<br />

pink plastic. She crosses her legs at the ankles and begins to swing them<br />

gently back and forth. She keeps swinging her legs and chewing her braid, and<br />

she does not answer when I call, so I call again.<br />

―Jessica!‖<br />

She opens her mouth and lets the braid drop out. The part she has been<br />

13

chewing has darkened from blonde to orange-brown with her spit. It falls heavy<br />

and sopping against her inner shoulder. She stops swinging her legs. She looks<br />

behind her, and then to the side, as though I might be calling some other Jessica.<br />

She touches her index finger to the bone between her little ice cream sundae<br />

tips of breasts. She looks at me and says, ―Are you talking to me‖<br />

―Yeah,‖ I say, ―your name‘s Jessica right‖<br />

―My name‘s Chelsea,‖ she says.<br />

―Oh,‖ I say, and look at William. He smiles and shrugs his little nutbrown<br />

knobs of shoulders. I ask Chelsea if she knows what time it is. She takes<br />

a pink cell phone from the pocket of her shorts and says, ―8:47.‖<br />

―Thanks. Sorry for getting your name wrong.‖<br />

She says, ―It‘s cool,‖ and goes back to her paperback, and starts sucking<br />

her braid again with great gusto. She is in for a trichinobezoar at this rate. William‘s<br />

mistake with Chelsea‘s name makes me wonder.<br />

―William, I‘ve been working with you for a couple weeks now,‖ I say,<br />

―Do you know what my name is‖<br />

William is treading water. He says, ―Umm,‖ and scratches his head. He<br />

forgets to keep treading water, drops below the surface, and begins to drown. I<br />

slip back into the water, grab him by the shoulder, tug him back up. He says,<br />

―Umm… I dunno.‖ I bring him to the side of the pool, grip him under the arms,<br />

and lift him out of the water. I climb out by the ladder and sit down beside him.<br />

I say, ―Okay, William. How about I give you three guesses‖<br />

―Okay.‖<br />

―Okay. Guess Number One. What‘s my name‖<br />

William scratches his head. He slaps his wet bathing trunks with his<br />

wet palms. He says ―um‖ for a long time. He puts both hands in the air, as<br />

though he is on a rollercoaster. He says, ―The Rock‖ My name is not The Rock.<br />

―No, William,‖ I say, ―my name is not The Rock.‖<br />

William says, ―Oh.‖ He picks his nose, and draws out a big, soggy, yellow<br />

booger. He wipes it on my arm. He does not do this out of malice. He does<br />

it because he has a booger. And my arm is there. I cup my hand, take some water<br />

from the pool, and splash it off. ―William,‖ I say, ―that‘s gross. Don‘t do that<br />

again.‖<br />

―Okay.‖<br />

―Guess Number Two.‖<br />

―What‖<br />

―What‘s my name, William Guess Number Two.‖<br />

William lies back. He puts his hands behind his head for a pillow. It<br />

looks like an excellent idea. I do the same. The sun is fully up now. It dries my<br />

suit and skin very quickly. I begin to feel a tight, pinched feeling at my temples<br />

and the crooks of my elbows. This means I am shrink-wrapped in an invisible<br />

sheath of dead chlorine. All the time I have been feeling these things, William<br />

has been saying, ―Umm.‖ Now he is done thinking. He turns his head to the<br />

side, to look at me.<br />

He says, ―French French Burger‖<br />

My name is not French French Burger.<br />

―French, French Burger‖ I say.<br />

―French French Burger,‖ William says.<br />

―William, what does that even mean‖<br />

14

William shrugs his shoulders. ―I dunno.‖<br />

―French French Burger‖<br />

―Yup.‖<br />

―Really‖<br />

―Uh-huh.‖<br />

―Wow.‖<br />

―That isn‘t your name‖<br />

―No, William,‖ I say, ―my name is not French French Burger. But I<br />

would be honored if you would call me that forever.‖<br />

William laughs. He slaps his belly. He kicks his feet in the water and<br />

churns up foam.<br />

―Okay, French French Burger!‖<br />

―Okay William, last guess.‖<br />

―Last guess for what‖<br />

―For my name.‖<br />

―You said to call you French French Burger.‖<br />

―I said call me that, I didn‘t say it was my name.‖<br />

―Oh.‖<br />

―So, last guess, William. What‘s my name‖<br />

William stops laughing. He does not say ―um.‖ He sits up very straight.<br />

I sit up with him. He looks at me very clearly and alertly, and he says, ―Mark‖<br />

My name is not Mark. Mark is the name of the counselor whose job it is<br />

to look after the day campers. William is one of these. He sees a lot of Mark, so<br />

it is perfectly understandable that he should make this mistake.<br />

―No, William,‖ I say, ―my name is not Mark.‖ And then I tell him my<br />

name, and William claps his hands. He throws his arms around my neck and<br />

says, ―French French Burger!‖ I pat him on the back and muss his hair. After<br />

the hug has gone on long enough, I take his hands from around my neck and put<br />

them by his sides. We sit for a moment and look across the pool. A breeze picks<br />

up. The blank log report flutters off the ground and over the fence. The bumblebee<br />

was the only thing holding it down. It has flown away.<br />

Aaron Greenberg<br />

15

a proper response to an old, white man who claims I shall know my place<br />

and write things asian-american<br />

my face is not all i am at all.<br />

so how dare you tell me to limit<br />

myself to writing asian-american<br />

things a lying jungle of railways<br />

occupy my mind as much as anyone<br />

else's, having gone to a lot of places,<br />

not just going down one path<br />

because nobody's life works that way.<br />

if my eyes were a few shades lighter<br />

and two sizes bigger, asian-american<br />

would suddenly have meant nothing,<br />

or wouldn't be expected in my pieces.<br />

why does my text necessarily<br />

have to reflect people's common<br />

beliefs about my face really,<br />

it's the trick of rumors people<br />

have spread of my face—and of others'.<br />

no expectation must be added<br />

to those rumors or writers with eyes<br />

appearing close to mine to write<br />

about asian-american identity<br />

questions/answers. is it because poets<br />

like me are oppressed to do so why<br />

shall i not get to write about beaches<br />

and letters like the girl with the ivory<br />

skin and turquoise eyes why does she<br />

never write about the color of her skin<br />

because she already knows that people<br />

perceive her as being too good that she<br />

doesn't need to inform them of the positivity<br />

of her whiteness so, she can write<br />

about the sun and moon. without sprinkling<br />

white-american adjectives to her work.<br />

i'm not subjugated by what my eyes receive<br />

from hateful people like you, sir.<br />

i, too, shall have a right to create my poetry<br />

as she does with hers.<br />

Debbie Chow<br />

16

eing comfortable with my feet<br />

Elizabeth Lawrence<br />

Digital photography

THE HEART, LIKE A BOCCE BALL<br />

The jack sits low in the grass. We‘re dead drunk,<br />

cannonballing across the lawn, gouging<br />

handful divots, each of us still nursing<br />

a tumbler of scotch brought home from the wake.<br />

We sons and brothers and cousins. I spin<br />

my ice and let that black-tie loosening<br />

buzz swarm. The others choose the sky, looping<br />

pop-flies that swirl with backspin, an earthen<br />

thud answering grunts while the soft dirt caves.<br />

I bowl instead, slow-ride hidden ridges—<br />

the swells buried beneath the grass—carving<br />

a curve, a line from start to stop, finish.<br />

The heart, like a bocce ball, is fist-sized<br />

and firm; ours clunk together, then divide.<br />

Luke Johnson<br />

18

the debonair locals<br />

they sit, Cezanne's card players, one slumped over a quarter-written story<br />

about two sunflowers that grew twisted in their own leaves. he gives dialogue<br />

to what was left after the wildfire, ashes blowing down blazers and dresses<br />

like a whisper. the other smokes pipe dreams and his tobacco eyelids<br />

deal out the next hand of sleep, sampling blood from his own bit lip;<br />

he chiseled his look after lions.<br />

in the south of france they drank absinthe, the emeralds rolling back time, curled<br />

like a moon into the top lip crescent. between whiskey slosh and wind chimes,<br />

autumn<br />

unfurled into black bare trees and alligator mud snapping back coattails, killing<br />

the gypsy moth in its decadent sleep. the cafe breeds leathered old men that<br />

foster youth in their gut.<br />

Kathy Transue<br />

19

Cusco, Perú<br />

Su rostro es sucio, pequeño,<br />

ojos negros como carbón me mira,<br />

la cabeza inclina en una manera<br />

que alinea su mandíbula con los grandes<br />

montañas verdes que rodea el pueblo.<br />

Ella lleva un chullo lleno de color—<br />

rojos, amarillos, anaranjados mezclan<br />

para coronarla, para realzar<br />

las mejillas redondas y rosicleres.<br />

Me agacho, ojos morenos conocen negros,<br />

su sonrisa la luz de su cara.<br />

La ofrezco una moneda y ella la agarra,<br />

dedos llenitos la envuelve. Sus pies cortos<br />

la cargan lejos de mi,<br />

delante de puestos de bolsas,<br />

de Inca Kolas y de tarjetas,<br />

a una mujer baja, su vientre hinchado<br />

y otro niño en sus brazos fuertes.<br />

La niña me mira, la mira a su moneda,<br />

sus ojos negros como carbón.<br />

Allison Hitt<br />

20

Route 7, Box 363<br />

Halter tops and frayed short-shorts,<br />

eighty degrees and climbing.<br />

Radio. Three girls laying stomach up.<br />

Pass the joint and take a hit.<br />

―I hate my mama.‖<br />

Bronzed thighs bond to a worn, wooden porch.<br />

Hair hangs from the porch stairs, crisping with sun,<br />

sticky rivulets drip and dry;<br />

lemon juice sweetens the darkest strands.<br />

The prettiest one wears aviators.<br />

―Blew a guy once and spat his load in his Coke bottle.‖<br />

Her eyebrows arch over her shades,<br />

―It‘s the real thing.‖<br />

Now dusk, bare feet in the grass,<br />

chasing fireflies, cupping light in their palms,<br />

as the mountains bruise to night.<br />

Amanda Mitchell<br />

21

Pattaya<br />

My wife Greta is still in bed, the lazy bitch, when I slam the front door and sling<br />

my brown leather trunk into the back of the taxi. It is appropriately sunny: I am<br />

glad to leave my frigid wife, at least for this week-long business trip in Thailand.<br />

I can‘t remember the name of the place; I know it sounds like an exotic fruit—<br />

juicy.<br />

The interior of the hotel lobby is silhouetted against the fierce noon sunlight;<br />

the receptionist‘s smile burns my wretched plane-dried eyes. As I hand her my<br />

passport, a well-groomed blonde comes up to the counter on my right. She<br />

flashes a clean white smile at the other receptionist, whose dark, slanted eyes<br />

register nothing. ―Welcome back, Ms O_____,‖ her plum-coloured lips say. The<br />

blonde and I get into the same lift. She hums a tuneless song, keeps her steel<br />

blue eyes on the rising numbers. We shudder to a stop at 13, and I watch her<br />

hips‘ restrained sway across the carpeted landing. I call a polite farewell after<br />

her, but she doesn‘t turn and smile.<br />

I‘ve had enough mai tais to last me till the morning—been getting up every half<br />

hour to piss in the tub. The floating numbers on my bedside table read three in<br />

the morning. I think of Greta, out for brunch with her biddy friends. Her perfect<br />

curls and red socialite grin swarm my drowsy mind, and I groan as nausea engulfs<br />

me. I lunge through woolly darkness to the bathroom. I meet my own red<br />

eyes as I raise my head from the toilet bowl. I‘ll need more alcohol before I can<br />

stomach returning to Greta tomorrow morning. Fucking Greta. I throw on<br />

khakis, a crisp white polo shirt, beach-worn sandals, and snap the door shut<br />

behind me.<br />

The lift makes no other stops. No blondes, only rowdy delight leaked in from<br />

outside crowds. I push myself out of the revolving doors and the heat of a spent<br />

day‘s air weighs like a whale on my bare forearms. Four blocks down is the Pink<br />

Feather Club, sign lit with bulbs flashing a disorientating green. I stumble in,<br />

miraculously locate the bar, and sprawl across the counter asking for three shots<br />

of clear tequila. The bartender bangs them onto the bar. I throw back three and<br />

spill the last one. I toss a bunch of sweat-smeared notes onto the counter and<br />

launch myself out of the booming club.<br />

Torches line the sand-peppered sidewalk, a tunnel of fairies. I follow them to the<br />

neon-puddled street where sex steams from the sewers. My throbbing eyes<br />

couldn‘t have missed them, those Thai girls rocking their proud hips down their<br />

pavement-catwalk—the locals don‘t turn a hair. I am entranced: black waterfalls<br />

down to derrieres, yellow urine bobs, paper thin necks arms legs smooth and<br />

brown teardrop tits cheap skirts small enough to fit around my wrist, giraffe<br />

22

eyelashes turned oil slick butterfly wings. One of them, twittering on a bench,<br />

catches my feasting eyes and swings her thighs open, flashes me her boy bits.<br />

Greta, safe at home in her cashmere cardigans, pearls and glowing angel hair,<br />

would have sucked in her scentless breath, clicked her teeth at the sight. Seeing<br />

my eyes lose focus, the ladyboy turns back to her friends, legs crossed, and my<br />

arousal subsides. A little temptation was what I came for—starving, I make my<br />

way back to the hotel.<br />

I revel in the cool of my spinning room, bare thighs and zebra stripe panties still<br />

swimming in my mind. Greta my ugly fucking wife, Greta with her shrill sugar<br />

voice cuts through my hazy reverie: she will start in with her screaming as soon<br />

as my taxi pulls into the drive—Did you fuck anyone Albert did you smear your<br />

cum all over her face was she young were her tits bigger than mine was her<br />

pussy tight Answer me, Albert!—and I will pay the tomato-faced taxi driver<br />

calmly, walk up to her, trunk in hand, and slap her.<br />

Tallula Ho<br />

Docks<br />

Catherine Stillerman<br />

Black and white photography

―Gentlemen‖ a found poem<br />

the prophet<br />

Was not sent to the eastern Man on October mornings<br />

with dizzying terms<br />

his discussions were In relation to benefit:<br />

This woman is not Evil, or Ugly<br />

like money.<br />

Amanda Gaye Smith<br />

24

Saint Michael Lights a Candle<br />

Amy Dixon<br />

25

The Reluctant Monk Ponders the Loss of his Hair by the Sea<br />

At the edge of the sea the wind is angry,<br />

its fists punch up the water to create foam<br />

sloshing like a drunkard who wanders<br />

away from his home.<br />

The land, too, is uneasy, dips and curves,<br />

forms now forbidden to my kind--<br />

I touch the rocks, cup my hands<br />

around them, but they are harder than I‘d like.<br />

Miles away my future brothers are chanting,<br />

their voices thump against my ears,<br />

a reminder of what is to come--<br />

Once I leave this landscape,<br />

the monastery will be waiting<br />

to slide a glinting razor across me,<br />

lopping off my locks.<br />

Anya Work<br />

26

Experience<br />

Updating the Record Book: 2008<br />

I‘m meticulous about going to my computer, opening the document titled<br />

―Numbers,‖ and adding the new name--if I remember it. Every boy is sorted<br />

into either the sex and/or fellatio category or simply added as miscellaneous.<br />

This is not a sex life; it‘s a job title.<br />

Previous Experience:<br />

I worked as a lifeguard one summer at a pool thirty feet away from the<br />

Delaware River. After days of rain, the river flooded and the thick, black mud<br />

filled the pool and covered the grass. As I steered full wheelbarrows back to the<br />

river, I wondered where it all came from. Clear water. Silver fish. Yellow flippers.<br />

Gray rocks. Tan sand. Green weeds. Brown dirt. They were all so beautiful<br />

on their own, but once too many of them were added together, the black took<br />

over.<br />

Working Overtime: 2007<br />

Benny was an aspiring musician. He sang one of his songs for me before<br />

we started the movie. After twenty minutes on the burgundy couch in his<br />

darkened apartment, I told him I had other places to go that night. He smoked<br />

a cigarette after I finished.<br />

On my way home, I got a text message from Mike. I knew him from<br />

elementary school. We met in a supermarket parking lot, and I got him off<br />

while he watched for the flashing red and blue of a cop car. It was a waste of his<br />

time though, the lights never came.<br />

By that point, it was too late to go home, so I met my friend at a party in<br />

Nazareth. I shared a bottle of rum with my gay friend Drew, but once he passed<br />

out, I found someone else to talk to. He helped me stumble to his car. My<br />

friends told me later I blacked out while he was on top of me.<br />

Scheduling Appointments: 2006<br />

I worked with Erik at the YMCA on Tuesdays. We hid between the yellow<br />

school busses in the parking lot and hoped security wasn‘t watching the<br />

cameras. He assured me the grainy gray pictures would camouflage us even if<br />

they were.<br />

In the spring, Chris and I met after school and after his girlfriend drove<br />

away. I appreciated his car; it protected us from the rain the sky threatened to<br />

spill. Our scheduled meetings lasted longer than their relationship.<br />

Scanning the Want Ads: 2005<br />

Pat and I usually got along but not when we were at a party with hot<br />

girls. At one party, he ran into some girl he cheated on me with. Not wanting to<br />

disrupt their happy reunion, I went outside by myself. Eventually, Billy came<br />

out and started talking to me. We talked for three hours before he even asked<br />

for a kiss, but it didn‘t take long for a kiss to turn into more. He politely asked<br />

for my number. It reminded me of the way I used to ask my mom if she needed<br />

help with the dishes as she dried the last cup.<br />

27

The Real World: 2002<br />

It was almost my 12 th birthday when I was allowed to go on vacation to<br />

California to visit my aunt and two cousins by myself. The first night, I slept in<br />

my cousin‘s room. He slept on the floor. I was still awake when he stood up and<br />

felt him walking toward me in the darkness. It must have felt like kissing his<br />

own hand, because I tightened my lips as hard as I could. His hand moved up<br />

my pajama top; I wished I was old enough to wear a bra. I squinted to watch the<br />

door, and I prayed to see footsteps breaking up the white strip of light underneath<br />

it. The wind carried an early birthday gift in through the open window. I<br />

heard familiar songs from a nearby Eminem concert. I listened. He finally finished.<br />

A thin, blue sheet was the only protection I never knew I would need.<br />

Freeloader: 2001<br />

My first crush: Michael James. He was older than I was, but he lived in<br />

my neighborhood, so I saw him a lot. We hung out in a fort we made in the<br />

snow surrounded by evergreens. I had always appreciated the way the white<br />

acted like a giant eraser: covering up all the imperfections on the ground.<br />

I knew we would kiss for the first time that night. We walked back to<br />

his house and watched a movie. I tried to freeze the picture in my memory. Our<br />

ankles crossed, our hands interlaced, our heads overlapped. I wished it would<br />

never end. I had nowhere else to go that night.<br />

Callie Bonatz<br />

La Primogenita<br />

Shazy Maldonado<br />

Black and white photography

1967<br />

Like a cyaneous Sagittarius sunburst<br />

Remembered ingeniously as doxologies in silence<br />

Deliberately chokes behemoth on Beatles albums<br />

Diarchy eschatology; isoprene, I dream of Jeannie<br />

Reeling gridelin seriatim<br />

Retrophilia unctuous.<br />

Ostentatious comeuppances feeling around dour percussion<br />

Lilaceous karrozzins, electric Kool-aid, and the mired crumbs of Mariolatry<br />

Xenolith and cymbals; solipsism suckles color television,<br />

Vietnamese girls have phytosophy in their pinkie toes<br />

Hippies chew nubiform brains<br />

Cannot stop the windy rain because circularly we are in the Combine<br />

Oviform hegemonic monikers: LBJ, JFK, and cuckold KKK.<br />

A summer of love vulviformed into lyrate constellations,<br />

Waltzed tristiloquy with sicilienne imaginary colors of a<br />

Year‘s eponym.<br />

Brittany Jamison<br />

29

Origin<br />

In the back of your `89 Charger, you breathe a filament of smoke into my navel.<br />

Djarums are all you ever touch, the velveteen wraps treated like jewels, like me.<br />

"My mercury's in retrograde," techno salve for punk-sore bones.<br />

Galvanized, electric: this is me. Drunk inside your burgundy thermos.<br />

Once, a woman asked if you were of Cherokee descent. She said,<br />

"It's those cheekbones. But your nose... your nose, now that's from Israel."<br />

You smiled and said, "Ma'am, I'm Italian." and took her order<br />

with your middle finger poised behind the notepad.<br />

It still makes me laugh. I touch those cheekbones now, that nose, that mouth<br />

the color of an Easter egg, this tongue flavored with papayas, with pot.<br />

I don't know where you came from either. It was not Italy. It was not Israel.<br />

You are neither romantic nor holy enough.<br />

We're arcane and this is all I care to know. I plan to sleep tonight.<br />

Slip me something stronger than hymns born from your throat.<br />

Retrograde. When I am older, and I have left you,<br />

I will sculpt those cheekbones in phantasma; I will be your Creator<br />

And I will carve you to life. A clay statue of your face will conduct my sleep.<br />

When I awake, the air will smell like tobacco, like cloves.<br />

I will breathe so greedily.<br />

Taylor Hodge<br />

30

Okay, so this is how the universe works<br />

Kathy Transue<br />

Black and white photography

Stream of Mock Love\(Consciousness)<br />

walls flooded by pink paint, cups of sugar done up into solid goods, caramel performers<br />

showed off fancy curlicues, now stuck on linens and sheets, little fairies<br />

wore jeweled blonde buns on their heads, who are woven in cloth inside and out,<br />

canned peaches dunked in clear melted sugary syrup lost all sense of sourness,<br />

soft pillowy white softness on the kitchen curtains with light blushing pink haze<br />

spread out—<br />

i saw her white hand with those really long fingers,<br />

merely bones covered lightly in thin wraps of clear skin,<br />

which stuck out from underneath a red cotton blanket.<br />

gold polish on her fingernails. lots of tiny glitters on those half<br />

ovals.<br />

i couldn't focus. her bedroom was so pretty. skinny vases,<br />

fat vases, every one formed into female curves. yes, lined<br />

up against the wall around the whole room on a beige carpet.<br />

words on the walls given birth by a black permanent marker;<br />

a total slave of the poet in bed. deep purple ink blotted<br />

and squirted across the black sky outside her window---<br />

one half of the window's face was covered meekly<br />

by a burgundy curtain---probably many glasses of wine<br />

has spilled itself on it repeatedly. her eyes were green marbles;<br />

wavy flowing lines of tan saturated into them.<br />

her eyes were on the ceiling. she blinked. her black hairs were vines,<br />

laying dazed on her three pillows. white lace sewn around her pillows'<br />

faces.<br />

so lovely. she was beautiful. her cheekbones looked cold. i sort of<br />

wanted<br />

my palms to radiate her cheeks, but i left her still figure alone.<br />

she was far too pretty at the hour of nine-sixteen.<br />

i started to see blood dripping.<br />

dripping from the top of her head onto her left cheek.<br />

i blinked rapidly---no, no---i was wrong. no blood.<br />

her breath suddenly stretched. she closed her eyes. her breathing<br />

relaxed.<br />

i tried to concentrate on the form of her flesh. i thought i heard a pair<br />

of heels tap on stairs. i loved her so much.<br />

yes, i loved her. her crystal earrings sparkled<br />

on hooks hanging on the inside of her closet door,<br />

each pair held hands, made shine together. i smelled<br />

eight candles: melon, papaya, apple pie; three kinds<br />

of candles got along to make one fragrance.<br />

32

"what makes you wonder"---<br />

notebooks in her drawers muffled their giggles with their hands.<br />

there were stripes, plaid patches, and criss-crosses of yellows<br />

experiencing first encounters with greens. so many clothes in piles<br />

on chairs, stools, and under her bed. no violent yelling.<br />

no scream that pierced any holes on my skin.<br />

i noticed those objects everyday. when i went outside<br />

to take walks, i watched families and groups of friends.<br />

lots of smiling, patient listening. leisure in their feet.<br />

their voices were rivers without running into obstacles.<br />

trees and rocks in calm postures. so much sunlight.<br />

the beautiful poet in bed---and i---<br />

her cheeks were permanently injured<br />

by the smacks of my hands. driven by her angry<br />

long slender fingernails, i had red-brown crusted<br />

creeks hang along my arms, chest, and face.<br />

she had an old woman's eyes.<br />

they were like overworked mangled hands.<br />

yet, she was a stunning human goddess.<br />

no, no---i couldn't think.<br />

closing my eyes,<br />

i left her bedroom. i crept downstairs. i truly did love her.<br />

i had to drive away for a while. i looked at neon lights<br />

down main street. in my car, driving, i heard loud music<br />

in bars, in lounges. blood cracked on my hands.<br />

kept driving. parked my car in a parking garage.<br />

i stepped into a restaurant, passed by tables.<br />

everyone was like one wall of colors mixing<br />

into one another. laughter became louder.<br />

lots of voices all had a good time. each had a hand<br />

to hold or an arm around their shoulder. i felt sick;<br />

my pulse prompted me to the men's room. i stared dumbly at the violet<br />

puffiness under my eyes. i rinsed off the blood on my arms.<br />

i loved her. she couldn't keep quiet. i shut her mouth<br />

with my hands. i hated how all the colors in her bedroom<br />

drove me crazy, singing and dancing into each other.<br />

she was so beautiful. i tried to grin.<br />

i saw a blade appear. it attacked her.<br />

it was on my side. it helped me quiet her down.<br />

she was so beautiful.<br />

potted plants stretched their green arms out to reach and touch<br />

me. they wanted to ask me if my day was alright. lavender, red, orange, yellow,<br />

purple tulips looked up at me to greet me as they sat on spots of soil living in the<br />

33

ushes', and potted plants' faces. their heads were so low, i couldn't see their<br />

joyful yellow faces. yes, more sadness. more dark hands. i felt no mercy from<br />

the clouds ready to drop rain.<br />

Debbie Chow<br />

Le Coucher du Soleil sur le Sahara<br />

Jeanette Jo Price<br />

Digital photography<br />

34

Queenswalk, November<br />

We are never on our knees.<br />

boat touching boat, crowing defiant.<br />

The gull blazes down,<br />

molten gold leaking from its mouth,<br />

no olive branch to rub frost from railing<br />

or touch the river's rough tongue.<br />

The water lifts itself<br />

shoulders straining<br />

(the river never freezes anymore –<br />

it is too thick)<br />

When did these chains snap and speak<br />

with teeth like bells to clamour over the walls<br />

where the tide rushes up the stairs<br />

Domes still sucking sunlight on the north bank,<br />

moss and copper, shuttered against all nocturnes,<br />

whose eyes are wide enough to swallow the streetlights,<br />

the streets, the hands holding and feet<br />

that knock the cobbles.<br />

Rush and flood<br />

the bruised elbows and tender backs of bridges<br />

Hammer where the rusted shore crumbles<br />

and beachcombers straddle the rocks,<br />

hunting, with torches, for Roman tiles,<br />

a mosaic ceiling fallen in,<br />

now stiffening the river bed with bites of colour.<br />

We were ancient once now we are forgotten.<br />

Renee Branum<br />

35

Word Problem: Post-Colonial Theories<br />

Two people are talking on the phone, stretching East<br />

Coast into West Coast. Compare the ratio of moon-pulled<br />

tides to sand-blasted honey ginseng waves.<br />

A compass<br />

points southeast, ships harbor<br />

on secondhand piers. All holy, all the time.<br />

Prayers circle the mouthpiece, where all breaths<br />

renounce and repent. He hears the singular<br />

whisper, the exaltation that<br />

conducts gravity.<br />

They celebrated Easter once with champagne<br />

at six forty-seven in the morning. The chimney<br />

threw out ashes, the kitchen floor<br />

scattered ripped fabric. The ocean slumped<br />

over outside.<br />

Garlands fall where words should, thorned bouquets<br />

decorate the conversation like punctuation. A pause,<br />

a white rose.<br />

She saw the stretch of highway<br />

median, wildflowers blurred the atlas.<br />

Summer drove her into hiding. He<br />

cleaned the house the day she left.<br />

Through the static, he reprises hallelujah.<br />

Kathy Transue<br />

36

Ladybug<br />

The woman woke in the bruised morning to find a ladybug in her bed—a flaky<br />

red jewel spotted with earth. Perhaps he was attracted to the woman‘s stemmed<br />

legs, the spiced mound they held up like an offering. A hand wrinkled blue<br />

sheets as a face peered close at rust-red wings, noticing the fracture between<br />

and wondering if anything could be planted there, if something might grow out<br />

of broken red earth… perhaps she was more than a sliced open wound, perhaps<br />

he was more than a display of misshapen stains.<br />

Emily Campbell<br />

37

Mail Pouch<br />

Tess Waugh<br />

Digital photography

Avon Girls (excerpted from a longer work)<br />

It was raining and everyone was going inside. Arlene said C‘mon baby,<br />

we‘ll do you up. She had her hair fixed, smelled like White Musk perfume and<br />

tissue paper. Her Avon friends smoked Capris on the porch. Marietta Sensenbrenner<br />

had a cigarette lighter shaped like a lipstick, said Get on out the mud<br />

and come get gorgeous, rang the doorchimes and disappeared. But Dorcas was<br />

looking at a squirrel.<br />

It was an ugly squirrel with a patch of missing fur on its hind-end that<br />

could have been a dog-bite – could have been mange. A front-yard squirrel,<br />

fearless and stupid as mud, under the damned old oak tree. An old one because<br />

it was fat around and had to be, and damned because it stuck the gutters full of<br />

leaves and the garden with squirrels. The squirrel was flapping around in the<br />

grass and smelling at the air. Dorcas took a sniff. Moss-cool, husky with smoldering<br />

leaves. When a raindrop hit on him, he flipped his tail, chirped, went<br />

back to smelling and scuffling over the roots.<br />

Dorcas scooted on her bottom towards the scabby thing. It had a little<br />

fringe of red around its eyes and its bald patch was speckled with little pink<br />

pores. She held out her hand and clucked, rocking on the balls of bare feet. The<br />

squirrel blinked. Its eyes looked wetter than rain. Dorcas snapped her fingers<br />

to watch the lids flash up and down, lashless and quick. Wet-eyed squirrel.<br />

Damned old oak. The rain diddled through the leaves and onto her back in cold<br />

plops. Leaves rolled up, silver-bellied. The screen door snapped in its frame.<br />

The first thunder was far-sounding as trucks down the highway. Dogbite<br />

squirrel, Dorcas figured. Quentin-bit. It scrambled up into the damned old<br />

oak as fast as if it were falling the other way, and Dorcas wondered how it was<br />

that they never seemed to fall, the squirrels, not from the power lines, the birdfeeders,<br />

the chain-link fence around Wee Wisdom Daycare. She worked at a<br />

starburst of dandelion and clover until the roots undid, threw them at the<br />

damned tree‘s trunk, left dirted prints on the screen door headed in.<br />

Quentin stumbled from behind the Maytag, beat his tail against the plywood<br />

floor. A dryer sheet hung from his fleecy jaw. He lapped the clay beneath<br />

her nails and fell beside her, flinching in his sack of skin as the roof-slap settled<br />

in the cove. Arlene and her Avon friends rattled in the kitchen.<br />

When the damned old oak fell through the kitchen next season, this is<br />

what Dorcas would think of: Quentin‘s warm skull, Apricot blusher, the halfeaten<br />

squirrel in his nest.<br />

Erin McKee<br />

39

Seven half diminished seven<br />

Danny likes to fuck retarded girls<br />

he explains, nicotine lipped,<br />

ash stacked pinky thick,<br />

they complain less.<br />

Coarse handed, he takes my lipstick stained<br />

coffee mug, abounding his.<br />

Grey tongued he licks the rim<br />

savoring the taste of skin cells and wax.<br />

Look, he says,<br />

ash teetering.<br />

Amy Dixon<br />

40

Untitled<br />

Kelly <strong>Hollins</strong><br />

Digital photography

Praise For A Sick Woman<br />

Her head<br />

wrapped, doo wrapped: another patient, another day, waiting in chairs at the<br />

Urgent Care.<br />

Head held<br />

sideways, temple propped by two fingers, supported at the elbow sleeping on<br />

the armrest. Her legs crossed, right over left, foot taps in random flutters of<br />

three.<br />

Tap-Tap-Tap<br />

like the crutch of the high school cheerleader three rows back.<br />

Strains<br />

of sick moans waft out from behind closed doors. The cough a man makes down<br />

the hall, the scratches I itch on my scalp: noise is noise is noise.<br />

A woman<br />

in purple jeans, purple socks, purple Keds, paces the carpet with a mason jar of<br />

black coffee.<br />

All of this<br />

in a room where the clock on the wall is a whore, a slut: men and women eye the<br />

arms, hands, legs of the clock incessantly as tongues slide across lips, and waiting—<br />

Waiting<br />

for their name to be called. The clock moans, Tick Tock Tick. Everyone has had<br />

a look, has had a feel for the time. All come at different times and all await their<br />

turn.<br />

―Alexis Papadopolous—the doctor will see you now.”<br />

With her<br />

head wrapped, doo wrapped she enters behind closed doors. Like the rest of us,<br />

patients, with or without patience.<br />

Except<br />

Papadopolous being the only black patient among us.<br />

Indiscreetly<br />

a nurse shortly enters. I watch her carry on menial chit-chat, with a patient,<br />

about Days of Our Lives from the day before. She pops a rubber glove, ―Oooooo,<br />

evil Stefano.‖<br />

42

Pops<br />

the other one, now shielding both hands. ―…God love its little haw-rt…”<br />

(Recognizably Southwest Virginia, an Appalachian waiting room.)<br />

The nurse<br />

masks her nose and mouth and carries a spray bottle of bleach. Another nurse<br />

enters, also masked, holds a white bed sheet in her gloved hands. I saw the eyes<br />

of masked nurses, saw the hands spray the chair, and neighboring seats, where<br />

poor Papadopolous waited.<br />

Threw<br />

out the magazines her infected fingers breezed through and spread the sheet<br />

across the row of chairs like a dead body.<br />

The crack<br />

of the white sheet in the air catch the eyes of the patients. The waft and gentle<br />

breeze of spring mountain detergent catch mine.<br />

The hungry<br />

bellies of gossip awaken. Whispers swell up, fester like an unkempt wound.<br />

What lives in a room takes on the spirit of the room. In this case, disease and<br />

infection of panic.<br />

―Yeah…well, it was that Nigger.”<br />

“…It must have been AIDS.”<br />

“…Didn’t you see the masks It couldn’t have been AIDS, it was<br />

something airborne.”<br />

“…You sure she was a Nigger Maybe she was one of<br />

them Arabs.”<br />

“…Terrorist…”<br />

“Yeah! A terrorist!”<br />

“A TERRORIST”<br />

“I HAVE KIDS TO LOOK AFTER.”<br />

“She could be a Leper…”<br />

Papadopolous<br />

has legs, has feet, has hands, fingers; no stubs of joints with finger bones poking<br />

through still infected with active Leprosy: growing and eating her flesh<br />

before our very eyes. She carries herself without secrets, without shame.<br />

Dead skin<br />

Flurries from my hand like dust, salt, snow. I should say something, truly something<br />

must be said. Leave the woman alone. I say nothing.<br />

I see<br />

impatient women and their gravy satisfaction with hair hung golden or black, to<br />

the shoulders or pinned back, velvet.<br />

43

A booger<br />

smeared into the chair, in a sticky situation I sit silent, useless: mucus. Speak!<br />

Say, leave her alone. Mutter, mumble, stutter. Anything. Say something, damnit.<br />

They gnash<br />

against her with their teeth. They cry out with a loud voice. The woman in purple<br />

socks stops their ears and opens their mouths. They run on Papadopolous<br />

with one accord. They cast her out of the Urgent Care and stone her.<br />

The lady<br />

in purple socks stands up to shout at the nurse:<br />

“You know I have Lupus and the Lord Jesus Christ has my back. I<br />

could right now drop dead in the floor and I would be happier than all ya’ll in<br />

this room. I have lupus and we have a right to know what that girl brought<br />

into this clinic. We have a right to know!”<br />

Everyone<br />

together now,<br />

―Yeah! Yeah! We have a right to know! We do!”<br />

The nurse<br />

closes her eyes and holds both palms in the air as if she has nothing to<br />

hide. She says:<br />

―Okay, okay, everyone needs to settle down. That is confidential information<br />

and I am not at liberty to discuss this with ya’ll. I assure you<br />

that everyone is alright.”<br />

“Oh yeah,”<br />

demands the woman in the purple socks,<br />

―what about the masks and the spray, the white sheet over the whole<br />

row. I saw you confiscate some woman’s jacket that was sitting on the row<br />

with that Nigger.”<br />

“Mam, you will not use such language in this office or you will be<br />

asked to leave.”<br />

“I am six weeks away from my due date! Tell us,”<br />

shouts a bleach blonde pregnant woman,<br />

―we have a right to know!”<br />

All<br />

together now,<br />

―Tell us! Yeah! We have a right to know!”<br />

Before me,<br />

a nightmare: where every breath is aimed at Alex Papadopolous. And I say nothing.<br />

Silent. Left in loneliness I want something I am not strong enough to have.<br />

44

The eyes to calm and stare to break the panic.<br />

In my silence<br />

I begin to sound like them, imitate them. Even though I did not verbally condone<br />

this behavior, my silence speaks. My silence said enough.<br />

The woman in purple<br />

socks stands up with one hand in the air. She says,<br />

―Lord Jesus Christ I’m hungry for Heaven!”<br />

She sits<br />

back down and crosses her legs, left over right. She whispers to the woman on<br />

her right,<br />

“I’m afraid of this big ole’ world, I tell ya. I have Lupus by the way…”<br />

As the whispers<br />

die down Papadopolous comes back. Silence fills the room like stagnant lingering<br />

flatulence. I held my breath.<br />

“That’s her…she ain’t no terrorist. It’s probably AIDS.”<br />

The lady<br />

in purple socks stands up, nodding at her followers for reassurance. She says,<br />

―Jesus Christ be with me!”<br />

Slowly<br />

she approaches Papadopolous like one might approach a groundhog eating the<br />

produce from their garden. Stalks her like a pest, like a rodent.<br />

Torrential<br />

pulses beat from the lips of the woman in purple socks. My eyes open, startled,<br />

and ringed with salt of humiliating tears bleaching away the flesh around them,<br />

commiserating. How gracefully still she exited, with chin high and knuckles<br />

white.<br />

To hear<br />

the disgust sift quietly away and sighs of relief fill the room like a fever. And all<br />

the while the woman in the purple socks follows her out with hand sanitizer and<br />

Kleenex, wiping clean everything her hand touches.<br />

Praise for a sick woman.<br />

Praise for sinew within the flesh.<br />

The woman in purple socks<br />

comes back in, wiping her hands as if she has, in fact, truly rid the office of that<br />

pesky ground hog, like a thank you is in order. Like a dog bringing home a dead<br />

baby bunny and leaving it on your woolen slippers. Woof Woof Woof to the lady<br />

in the purple socks.<br />

45

I see<br />

Papadopolous through the blinds. She picks up a piece of trash and puts it in her<br />

purse. Another piece and another, without a trash can in sight. A car stops to<br />

pick her up. I see her holding her baby from the backseat (she puts on a doctor‘s<br />

mask to do so).<br />

Tap-Tap-Tap<br />

my finger to the glass in hopes of breaking my silence. Hail.<br />

Praise for a sick woman. Praise her.<br />

Praise for sinew within the flesh.<br />

Helen McKinney<br />

46

Gesture<br />

Leigh Werrell<br />

Monotype

Homme nu, homme noir<br />

I.<br />

Homme nu, homme noir<br />

Tes mains bénites qui prient,<br />

genoux saints qui plient pour<br />

ta croissance, pour ta Dieu.<br />

Héro modeste, simple.<br />

Cœur blanc, corps noir<br />

la couleur de la vie,<br />

de tout qui est bien. Ta<br />

voix semble le vent d‘Est.<br />

Ton sang pur, la première race.<br />

Tes ancêtres ont bercé le monde.<br />

Homme nu, homme noir<br />

Sais-tu que tu es aimé <br />

Tes gouttes de sueur, étoiles<br />

sur la nuit de ta peau.<br />

Ta bouche m‘enveloppe,<br />

me nourri avec le vin<br />

noir de tes mots.<br />

II.<br />

Homme nu, homme noir<br />

Promised land. I dare<br />

discover you. Where<br />

after baptism and shahadah,<br />

we find communion in each<br />

other. Allahu Akbar<br />

We lift wine to our lips;<br />

the taste holy, as mercy.<br />

It cleanses like prayer.<br />

Homme nu, homme noir<br />

Our communion drips<br />

from our hands. We tore<br />

into it like ripe fruits without pits.<br />

Jeanette Jo Price<br />

48

Untitled<br />

Tiffany Robinette<br />

Digital photography

Pure Gold<br />

Tess Waugh<br />

Digital photography

Fifth Annual<br />

National Undergraduate<br />

Poetry & Fiction Competition<br />

This year, the Cargoes staff sent fliers to universities across the nation.<br />

We received many entries in both poetry and fiction, and generated<br />

an engaging and competitive pool of submissions.<br />

With the help of our fiction judge, Tony D‘Souza, we selected the<br />

work ―A Break From The Neighborhood.‖<br />

"In a field crowded with careful character studies, ‗A Break From The<br />

Neighborhood‘ stands out for the way the protagonists Tristan and<br />

Omar come to life as they wander through the Boston neighborhoods<br />

they haunt, always on the edge of trouble. The author displays a maturing<br />

craft in his decision to let Tristan and Omar live and breathe<br />

without heavy authorial manipulation, dressing them up neither as<br />

better nor worse than they are, letting them 'drive' the story as he<br />

takes a distant, and wisely chosen, artistic backseat. Boston itself<br />

becomes a leading player in the work, and the author's attention to<br />

dialect and language is noteworthy."<br />

-Tony D‘Souza<br />

With the help of our poetry judge, Claudia Emerson (Pulitzer Prize<br />

Winner, 2006), we selected the work ―From an Old Maid to Another.‖<br />

―‗From an Old Maid to Another‘ was chosen for its exploration of the<br />

nature of isolation and imagination, and also for its formal poise despite<br />

the disorientation of the woman and the skillful confusion of<br />

her house and yard.‖<br />

- Claudia Emerson<br />

51

A Break From The Neighborhood<br />

―Stay awake to the ways of the world cause shit is deep.‖<br />

-Wu-Tang Clan, ―C.R.E.A.M.‖<br />

―I‘m walking to my coffin<br />

Drinking poison from my chalice.<br />

Pride begins to fade,<br />

And you‘ll all feel my malice.‖<br />

-Dr. John, ―I Walk on Gilded Splinters‖<br />

Tristan and Omar had one big thing in common aside from being halfblack,<br />

half-Dominican and not knowing shit about the Dominican half (except a<br />

Spanish curse word or two): both their fathers had been stick-up boys, legends<br />

on the street, afraid of nobody. They would rob the wiseguys from the North<br />

End, the last of the Mafia in New England. They would rob the white trash that<br />

sold meth and crank from behind their bars in Dorchester and Southie. They<br />

would take on the Vietnamese, their psycho reputation be damned, fresh off the<br />

boat and into Savin Hill and Fields Corner with raw knockout dope straight<br />

from the poppy plants of their homeland. And when it came to people from their<br />

own neighborhood, Omar‘s father, Antonio Wright, had this pearl of wisdom to<br />

say: ―Fuck them niggas. Hate to say it, but local boys is the easiest motherfuckers<br />

in the world to take off.‖ He‘d been dead six years now, since Omar was ten<br />

and Tristan eleven; caught with a pistol and then shanked in central booking<br />

before he even made it to trial.<br />

Tristan Clark, senior, went down on the corner of Northamton and<br />

Reed, a block away from their building in the Roxbury Corners housing project,<br />

after a crew of Irish guys came down to the neighborhood and shot him a dozen<br />

times. At least, that‘s how the story was always told. Tristan didn‘t know how<br />

true it was and didn‘t really care. He wasn‘t proud of the way his father died, but<br />

it made for a great story. On more than one occasion, blunted off his ass, he‘d<br />

tell it like some ancient myth. ―The Legend of Big T,‖ he would call it, always<br />

trying not to laugh. One time, it loosened the legs of this one girl, Shantelle or<br />

something like that; he didn‘t really remember her name. Even though it was his<br />

first time, there was no reason to remember her. All that stuff about how the<br />

first time was supposed to be so damn good wasn‘t true. It was like most everything<br />

else in his life- it was just something that happened, not worth forgetting<br />

or remembering, another moment in a seventeen-year series of moments. Roxbury<br />

was like that. It wasn‘t some Boyz N the Hood bullshit with people getting<br />

shot every five minutes. His mother once described it like this: ―Be like waitin<br />

for the Orange Line…people stuck in one spot, just waitin around for something<br />

to happen, gettin frustrated, cause ain‘t nothing ever gonna change. That train<br />

always late.‖<br />

When Big T got dropped, Tristan knew people would always remember<br />

it. He knew that whatever he did in his own life would probably pale in comparison<br />

to the infamy his father gained by simply being who he was and getting shot<br />

52

down for it. No matter what, Tristan, junior, would always be Little T.<br />

One Saturday afternoon, after riding the T to Chinatown, Tristan and<br />

Omar got off and walked down Washington Street through Downtown Crossing.<br />

They had almost a dozen G-packs of dope and coke vials left from what their<br />

fathers had stolen and saved. From summers of clocking it on the corner and in<br />

the courtyard of their building, taking bullshit from fiends and other dealers,<br />

they had just enough money to indulge their few vices and not attract too much<br />

attention. Omar lived to collect shoes and Tristan lived to collect music, but<br />

other than that they didn‘t throw their cash away.<br />

At one point they were in Hip Zepi, a store Tristan hated but tolerated,<br />

the same way Omar tolerated it when he would spend more than an hour trying<br />

to decide what CD to buy. He looked around at all the flashy, baggy clothes for<br />

sale, the Sean John and Ecko bullshit, the throwback jerseys, all of it pandering<br />

to the way clothing designers assumed black people his age liked to dress. It<br />

pissed Tristan off that their assumptions were usually right. It didn‘t matter that<br />

baggy jeans were about the worst thing to wear on the street. He remembered<br />

one time when Omar had to run from a roll-up squad of Narco cops, he tripped<br />

over his pant leg and they fell right the fuck down. The cops, the corner boys,<br />

people driving by, everyone who saw it was laughing so hard.<br />

Taking any elements of flash out of your appearance kept you relatively<br />

under the cops‘ radar, if you knew what the fuck you were doing. The flashiest<br />

part of Tristan‘s wardrobe was a black-and-white fitted Red Sox cap. Wearing<br />

with it a hoodie over a white tee and faded Levis, he looked no different from<br />

any other black or Hispanic guy on the street. Not like some mack-daddy<br />

motherfucker in a powder-white tracksuit, practically wearing a sign that read,<br />

arrest my black ass.<br />

Omar was looking at a pair of sneakers that were black and red, with a<br />

crossed pair of semiautomatics on each side. ―What kind of guns you think those<br />

are Glocks‖<br />

―How the fuck should I know‖ Tristan said.<br />

―Ain‘t you ever seen a gun, nigga I remember my pops had a .50, a<br />

fuckin Desert Eagle. He got it from some Mafia dude…must‘ve been the only I-<br />

talian he never ripped off or some shit.‖<br />

―Only guns I ever seen up close was revolvers. That‘s all my old man<br />

would carry. He‘d always say, a .38 don‘t jam, Magnum don‘t jam, but you get<br />

yourself a semiauto, like a .45 or a Glock nine, it‘s either gon‘ jam up or it‘ll go<br />

off in your damn drawers on account of it ain‘t got no safety.‖ As Tristan said<br />

this, he literally assumed the voice of his father. The slow roll of the words off<br />

the tongue sounding like some old-time R&B shit his mom would put on when<br />

she‘d have guys over, that was Big T right there. Tristan had a talent for picking<br />

up the voices of anyone he heard talking and incorporating them into his own.<br />

―Whatever, man. I‘ma go pay for these, then I gotta go see that nigga<br />

Errol and pick up for tonight. You go spend the next three hours lookin for a got<br />

-damn Big Daddy Kane CD,‖ Omar said, laughing.<br />

Tristan flipped him off in response, a wise-assed grin on his face. ―I will,<br />

motherfucker, and I‘m gonna enjoy it, too.‖<br />

53

―Hurry up with that shit, nigga,‖ Omar said. ―It‘s gettin cold out here.‖<br />

―I‘ll be done with it when I‘m done with it. Be patient,‖ Tristan said. It<br />

was around eight, four hours after they‘d split up so Omar could get weed and<br />

Tristan could go back and forth between FYE, Borders, and Newbury Comics,<br />

perusing the music selections in each store. Now they were sitting on the docks<br />

in the Public Gardens. Tristan dangled his feet over the water as he doublerolled<br />

more than half a gram of weed using one-and-a-quarter EZ Widers. Omar<br />

sat Indian-style, patiently waiting, not wanting to get his fresh new shoes anywhere<br />

near the water. After about four minutes or so of delicate work, he<br />

dragged his tongue along the glued edge of the paper, sealed it up, and handed it<br />

to Omar. ―Now look at that. If I ain‘t rolled that shit good enough to make your<br />

dick hard, I don‘t know what will.‖<br />

―Dag, Little T. You got a fucked up sense of what‘s funny, yo.‖<br />

―Whatever, man, go ahead and light that shit, quit wavin it around.‖<br />

The joint was a little hard to hit, but worth it. Omar coughed hard and<br />