Retrospective Versus Prospective Cohort Study Designs - Lippincott ...

Retrospective Versus Prospective Cohort Study Designs - Lippincott ...

Retrospective Versus Prospective Cohort Study Designs - Lippincott ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

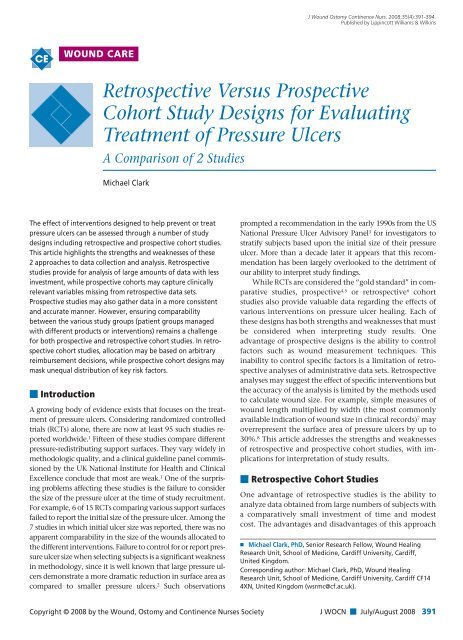

WJ3504_391-394.qxp 6/23/08 10:13 PM Page 391<br />

J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2008;35(4):391-394.<br />

Published by <strong>Lippincott</strong> Williams & Wilkins<br />

CE<br />

WOUND CARE<br />

<strong>Retrospective</strong> <strong>Versus</strong> <strong>Prospective</strong><br />

<strong>Cohort</strong> <strong>Study</strong> <strong>Designs</strong> for Evaluating<br />

Treatment of Pressure Ulcers<br />

A Comparison of 2 Studies<br />

Michael Clark<br />

The effect of interventions designed to help prevent or treat<br />

pressure ulcers can be assessed through a number of study<br />

designs including retrospective and prospective cohort studies.<br />

This article highlights the strengths and weaknesses of these<br />

2 approaches to data collection and analysis. <strong>Retrospective</strong><br />

studies provide for analysis of large amounts of data with less<br />

investment, while prospective cohorts may capture clinically<br />

relevant variables missing from retrospective data sets.<br />

<strong>Prospective</strong> studies may also gather data in a more consistent<br />

and accurate manner. However, ensuring comparability<br />

between the various study groups (patient groups managed<br />

with different products or interventions) remains a challenge<br />

for both prospective and retrospective cohort studies. In retrospective<br />

cohort studies, allocation may be based on arbitrary<br />

reimbursement decisions, while prospective cohort designs may<br />

mask unequal distribution of key risk factors.<br />

■ Introduction<br />

A growing body of evidence exists that focuses on the treatment<br />

of pressure ulcers. Considering randomized controlled<br />

trials (RCTs) alone, there are now at least 95 such studies reported<br />

worldwide. 1 Fifteen of these studies compare different<br />

pressure-redistributing support surfaces. They vary widely in<br />

methodologic quality, and a clinical guideline panel commissioned<br />

by the UK National Institute for Health and Clinical<br />

Excellence conclude that most are weak. 1 One of the surprising<br />

problems affecting these studies is the failure to consider<br />

the size of the pressure ulcer at the time of study recruitment.<br />

For example, 6 of 15 RCTs comparing various support surfaces<br />

failed to report the initial size of the pressure ulcer. Among the<br />

7 studies in which initial ulcer size was reported, there was no<br />

apparent comparability in the size of the wounds allocated to<br />

the different interventions. Failure to control for or report pressure<br />

ulcer size when selecting subjects is a significant weakness<br />

in methodology, since it is well known that large pressure ulcers<br />

demonstrate a more dramatic reduction in surface area as<br />

compared to smaller pressure ulcers. 2 Such observations<br />

prompted a recommendation in the early 1990s from the US<br />

National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel 3 for investigators to<br />

stratify subjects based upon the initial size of their pressure<br />

ulcer. More than a decade later it appears that this recommendation<br />

has been largely overlooked to the detriment of<br />

our ability to interpret study findings.<br />

While RCTs are considered the “gold standard” in comparative<br />

studies, prospective 4,5 or retrospective 6 cohort<br />

studies also provide valuable data regarding the effects of<br />

various interventions on pressure ulcer healing. Each of<br />

these designs has both strengths and weaknesses that must<br />

be considered when interpreting study results. One<br />

advantage of prospective designs is the ability to control<br />

factors such as wound measurement techniques. This<br />

inability to control specific factors is a limitation of retrospective<br />

analyses of administrative data sets. <strong>Retrospective</strong><br />

analyses may suggest the effect of specific interventions but<br />

the accuracy of the analysis is limited by the methods used<br />

to calculate wound size. For example, simple measures of<br />

wound length multiplied by width (the most commonly<br />

available indication of wound size in clinical records) 7 may<br />

overrepresent the surface area of pressure ulcers by up to<br />

30%. 8 This article addresses the strengths and weaknesses<br />

of retrospective and prospective cohort studies, with implications<br />

for interpretation of study results.<br />

■ <strong>Retrospective</strong> <strong>Cohort</strong> Studies<br />

One advantage of retrospective studies is the ability to<br />

analyze data obtained from large numbers of subjects with<br />

a comparatively small investment of time and modest<br />

cost. The advantages and disadvantages of this approach<br />

Michael Clark, PhD, Senior Research Fellow, Wound Healing<br />

Research Unit, School of Medicine, Cardiff University, Cardiff,<br />

United Kingdom.<br />

Corresponding author: Michael Clark, PhD, Wound Healing<br />

Research Unit, School of Medicine, Cardiff University, Cardiff CF14<br />

4XN, United Kingdom (wsrmc@cf.ac.uk).<br />

Copyright © 2008 by the Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society J WOCN ■ July/August 2008 391

WJ3504_391-394.qxp 6/23/08 10:13 PM Page 392<br />

392 Clark J WOCN ■ July/August 2008<br />

can be illustrated by review of a large-scale retrospective<br />

cohort study reported by Ochs and colleagues 6 in 2005.<br />

Ochs and colleagues 6 compared pressure ulcer healing<br />

rates among nursing home patients managed with group 1,<br />

group 2, and group 3 support surfaces. The 3 groups of support<br />

surfaces are based on US Centers for Medicare &<br />

Medicaid Services guidelines for coverage of support surfaces<br />

in the home healthcare setting. They can generally be classified<br />

as nonpowered support surfaces (group 1), powered<br />

support surfaces (group 2), and air-fluidized therapy<br />

(group 3). Data were extracted through a retrospective analysis<br />

of clinical notes, with formal reliability checks between<br />

the trained data extractors; this attention to interrater reliability<br />

represents a strength of the study. However, the key<br />

outcome measure, wound size, was calculated from reported<br />

maximum wound length multiplied by width. The inability<br />

to ensure the accuracy of these recorded measurements is a<br />

limitation of this methodologic design.<br />

Data were obtained from administrative data sets. The<br />

following criteria were used for inclusion in the study:<br />

(1) the resident had to be present in the facility for at least<br />

14 days; (2) have 1 or more pressure ulcers; and (3) placed on<br />

a group 1, 2, or 3 support surface. This yielded a total sample<br />

of 664 subjects drawn from a potential population of<br />

2,486 adult nursing home residents. However, it was not<br />

clear how many long-term care facilities contributed this<br />

total of 664 residents, and no comments are provided describing<br />

any potential differences in participating facilities,<br />

such as nutritional support and topical wound treatments,<br />

that may have influenced study results.<br />

Data were then analyzed in 2 different ways: (1) analysis<br />

by person, defined as the rate of healing for the largest pressure<br />

ulcer per resident over a minimum of 5 days and (2)<br />

episode analysis, defined as the rate of healing for all pressure<br />

ulcers per resident tracked over 7- to 10-day episodes. This<br />

latter approach, which broke each resident’s stay into discrete<br />

7- to 10-day blocks (or episodes), required a sophisticated<br />

statistical analysis that attempted to account for<br />

potential bias inherent where multiple episodes from multiple<br />

ulcers are combined. Despite the mathematical sophistication<br />

of this episode analysis, the independence of each<br />

episode from other episodes gathered from the same nursing<br />

home resident is doubtful. If a pressure ulcer is healing<br />

in one episode, it may be expected that similar progress<br />

would be seen in the next and subsequent episodes. In this<br />

summary of the study by Ochs and colleagues, 6 the validity<br />

of the episode analysis is weakened by 2 factors: (1) the potential<br />

for lack of independence between episodes and (2)<br />

the potential for error introduced when measuring relatively<br />

small changes in wound size between 2 relatively close<br />

points in time (7–10 days apart), especially given the inexact<br />

measure of wound surface area.<br />

In analyzing the data generated in their study, the<br />

researchers acknowledged that the 3 study groups lacked<br />

baseline comparability. 6 For example, residents allocated to<br />

group 3 surfaces were younger (mean age 67.9 years) than<br />

residents assigned to group 1 and group 2 surfaces (group 1,<br />

mean age 79.3 years; group 2, mean age 77.4 years). In<br />

addition, residents who had been placed on group 3 support<br />

surfaces typically had more pressure ulcers, and their<br />

ulcers were of larger size and greater severity as compared to<br />

residents placed on group 1 and group 2 support surfaces.<br />

This variability in baseline group characteristics is understandable,<br />

since group 3 surfaces (air-fluidized beds) are typically<br />

reserved for patients with multiple and/or severe<br />

pressure ulcers. However, the lack of comparability among<br />

the study groups reflects a frequently encountered challenge<br />

of using retrospective data when allocation to treatment<br />

groups is based on prevailing treatment and<br />

reimbursement patterns rather than random assignment.<br />

For example, given the more severe nature of the pressure<br />

ulcers among residents managed with group 3 support<br />

surfaces, it was not surprising that their pressure ulcers appeared<br />

to heal faster. Twelve years ago the US National<br />

Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel 3 noted that initial pressure<br />

ulcer size is a predictor of healing rate, with larger ulcers<br />

demonstrating a more dramatic reduction in dimensions.<br />

The regression analyses conducted by Ochs and colleagues 6<br />

reaffirmed this observation; they found that initial pressure<br />

ulcer size was the key predictor of healing rate, and commented<br />

that the “marked effect of initial pressure ulcer size<br />

masked other factors with a potential impact on the healing<br />

rate.” While retrospective cohort studies have the potential<br />

to identify important trends in pressure ulcer management,<br />

the inability to form comparable groups at baseline weakens<br />

their ability to compare the efficacy of specific interventions,<br />

such as the ability of a specific pressure redistribution surface<br />

to promote pressure ulcer healing. This was the case of Ochs<br />

and colleagues, 6 where the initial allocation of support surfaces<br />

based on clinical considerations alone resulted in the<br />

largest pressure ulcers being allocated to one treatment arm<br />

(group 3). This inevitably led to the observation that their<br />

wounds healed faster based on ulcer size rather than differences<br />

in the efficacy of the pressure redistribution surface.<br />

Ochs and colleagues 6 correctly concluded that this challenge<br />

is ideally resolved by conducting a prospective study that<br />

matches wound sizes among groups at the onset of the<br />

study. So where healing rates are to be calculated and compared,<br />

retrospective studies may fail to identify clinically relevant<br />

differences between interventions.<br />

Another limitation of retrospective cohort studies is<br />

their inability to assign each treatment option frequently<br />

enough to ensure the ability to perform a meaningful<br />

comparison to other treatments. Instead, specific interventions<br />

may occur only rarely in available data sets. For<br />

example, while multiple subjects in the study reported by<br />

Ochs and colleagues 6 were managed with group 1 and<br />

group 2 support surfaces, very few were managed with alternating<br />

pressure overlay support surfaces (Table 1).<br />

Sparse employment of a key intervention, such as an<br />

alternating pressure overlay support surface, precludes any<br />

meaningful analysis of its efficacy.

WJ3504_391-394.qxp 6/23/08 10:13 PM Page 393<br />

J WOCN ■ Volume 35/Number 4 Clark 393<br />

TABLE 1.<br />

Number of Nursing Home Residents Allocated to<br />

Different Group 1 and 2 Support Surfaces a<br />

Support Surface Group 1 Group 2<br />

Foam 350 0<br />

Water/gel 83 0<br />

Alternating pressure overlays 16 0<br />

Low air loss 0 62<br />

Powered pressure reducing 0 35<br />

Powered air overlay 0 12<br />

Nonpowered advanced 0 16<br />

pressure surfaces<br />

Unreported 14 0<br />

Total number 463 125<br />

a<br />

The total number of residents allocated to group 2 surfaces (n 125)<br />

exceeds the total number of residents noted by Ochs and colleagues 6 to<br />

have received group 2 surfaces (n 119).<br />

■ <strong>Prospective</strong> <strong>Cohort</strong> Studies<br />

In contrast to retrospective cohort studies, prospective<br />

cohort studies frequently require a considerable commitment<br />

of time and a robust budget. One example of a<br />

prospective cohort study that illustrates the challenges<br />

and benefits of collecting outcome data prospectively was<br />

reported by Clark and associates. 4,9 Their study initially<br />

involved 4 UK hospitals and 1 US hospital. It required 10<br />

full-time data collectors (in the United Kingdom) to gather<br />

data from a cohort of adult patients (16 years old) who<br />

stayed in hospital for more than 2 days, were able to provide<br />

consent (or assent was available from relatives), and were<br />

not cared for on psychiatry, ophthalmology, gynecology,<br />

pediatrics, obstetrics, or psychiatric wards. Data were gathered<br />

over a 2-year period from 2,507 UK hospital patients,<br />

representing 29,611 total patient-days. A further 1,202<br />

subjects were recruited at the US site; but differences between<br />

the countries in the availability of some data precluded<br />

combination of the 2 data sets. Specifically, data at<br />

the US hospital were gleaned from prospective review of<br />

medical and nursing records rather than direct patient<br />

observation. The primary focus of this prospective study<br />

was the effectiveness of support surfaces on pressure ulcer<br />

prevention, although data were also collected upon<br />

subjects who entered the cohort with existing pressure<br />

damage. A wide range of support surfaces was used in the<br />

study including low-air-loss, air-fluidized, foam, gel, and<br />

alternating pressure-redistributing mattresses and overlays.<br />

The study cohort involved 218 subjects with pressure<br />

ulcers; 100 were present on admission and the remaining<br />

118 developed in the hospital, representing an incidence<br />

rate of 42.6 people developing pressure ulcers per 10,000<br />

patient-days.<br />

<strong>Prospective</strong> data collection allowed for the inclusion of<br />

variables relevant to pressure ulcer development that may<br />

not be captured in a retrospective review, which is limited<br />

by the accuracy and comprehensiveness of previously<br />

recorded data. For example, Clark and associates 4,9 assessed<br />

the condition of the bed mattress and found that 15%<br />

(n 382) of the patients on foam mattresses received inadequate<br />

support (bottomed out) and 15 of the alternating<br />

pressure mattresses and overlays exhibited alarm signals.<br />

This level of detail is unlikely to be captured from retrospective<br />

data sets. Rather, it is only likely to be measured when<br />

full-time data collectors are available at each participating<br />

center. Interestingly, the condition of the mattress was not<br />

associated with a higher incidence of pressure ulcers.<br />

While prospective cohort studies offer advantages over<br />

retrospective studies, one weakness remains: the inability<br />

to form treatment groups that are truly comparable at<br />

baseline. If the study groups are not comparable, the data<br />

gathered may fail to reflect key factors impacting study<br />

outcomes, including the treatment options under evaluation.<br />

This remains a principal weakness of both retrospective<br />

and prospective cohort studies, for without true<br />

randomization at baseline it remains unlikely that<br />

differences in the comparison groups can be effectively<br />

controlled for, allowing selective evaluation of the treatment<br />

options under evaluation.<br />

TABLE 2.<br />

Comparison of the Benefits and Disadvantages of <strong>Prospective</strong> and <strong>Retrospective</strong> <strong>Cohort</strong> Studies Compared With<br />

Randomized Controlled Trials<br />

Randomized Controlled Trial <strong>Retrospective</strong> <strong>Cohort</strong> <strong>Study</strong> <strong>Prospective</strong> <strong>Cohort</strong> <strong>Study</strong><br />

Baseline comparability Lack of baseline comparability Lack of baseline comparability<br />

Narrow, defined population Wide population, potentially better Wide population, potentially better reflecting<br />

reflecting “real-world” care<br />

“real-world” care<br />

High internal validity Perhaps, low internal validity Perhaps, low internal validity<br />

Expensive Less costly Expensive<br />

Ability to determine data items to be Lack of ability to capture key variables Ability to determine data items to be captured<br />

captured<br />

missing from the data set<br />

Effect can be attributed to intervention May not be able to attribute results May not be able to attribute results to the<br />

to the intervention<br />

intervention

WJ3504_391-394.qxp 6/23/08 10:13 PM Page 394<br />

394 Clark J WOCN ■ July/August 2008<br />

■ Conclusion<br />

<strong>Prospective</strong> and retrospective cohort studies appear to offer<br />

valid alternatives to the RCT when exploring the effect of<br />

interventions used in pressure ulcer prevention or treatment.<br />

However, the relative strengths and weaknesses of the<br />

2 designs must be borne in mind; retrospective cohorts may<br />

be generated at relatively low cost but may miss variables of<br />

interest and fail to adequately reflect specific interventions<br />

within the cohort. In contrast, prospective cohorts are able<br />

to include specific variables and data can be collected with<br />

greater confidence in its reliability and accuracy, but require<br />

considerable investment of time and money and are therefore<br />

more difficult to perform (Table 2). In addition, both<br />

designs are limited by the difficulty of establishing truly<br />

comparable baseline groups. This challenge of baseline comparability<br />

suggests that there remains a strong place for wellconducted<br />

RCTs when exploring the impact of new<br />

interventions for pressure ulcer prevention of healing.<br />

■ ACKNOWLEDGMENT<br />

The author has no significant ties, financial or otherwise,<br />

to any company that might have an interest in the publication<br />

of this educational activity.<br />

KEY POINTS<br />

✔ <strong>Retrospective</strong> studies are relatively low cost but frequently<br />

fail to report on specific interventions.<br />

✔ <strong>Prospective</strong> designed studies require significant financial<br />

input but collect more valid and reliable data.<br />

✔ Initial wound size is a strong predictor of healing.<br />

■ References<br />

1. UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence.<br />

Pressure ulcers: the management of pressure ulcers in primary<br />

and secondary care. Clinical guideline CG029. http://www.<br />

nice.org.uk/page.aspxo/CG029&c/skin. Published 2005.<br />

Accessed November 1, 2006.<br />

2. Brown GS. Reporting outcomes for stage IV pressure ulcer healing:<br />

a proposal. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2000;13(6):277–283.<br />

3. Xakellis GC, Maklebust JA. Template for pressure ulcer research.<br />

Adv Wound Care. 1995;8(1):46–48.<br />

4. Clark M, Benbow M, Butcher M, et al. Collecting pressure ulcer<br />

prevention and management outcomes; part 1. Br J Nurs.<br />

2002;11(4):230–238.<br />

5. Clark M, Benbow M, Butcher M, et al. Collecting pressure ulcer<br />

prevention and management outcomes: 2. Br J Nurs. 2002;<br />

11(5):310–314.<br />

6. Ochs RF, Horn SD, van Rijswijk L, Pietsch C, Smout RJ.<br />

Comparison of air-fluidized therapy with other support surfaces<br />

used to treat pressure ulcers in nursing home residents.<br />

Ostomy Wound Manage. 2005;51(2):38–68.<br />

7. Eager CA. Monitoring wound healing in the home health<br />

arena. Adv Wound Care. 1997;10(5):54–57.<br />

8. Schubert V. Measuring the area of chronic ulcers for consistent<br />

documentation in clinical practice. Wounds. 1997;9(5):<br />

153–159.<br />

9. Clark M. Models of pressure ulcer care: costs and outcomes.<br />

Br J Healthc Manage. 2001;7(10):412–416.<br />

Call for Authors: Wound Care<br />

• Review articles, case studies, case series, and original research reports focusing on the potential role of unprocessed<br />

honey in wound healing<br />

• Review articles or original research reports focusing on the antibacterial properties of silver<br />

• Continuous Quality Improvement projects, research reports, or institutional case studies focusing on innovative<br />

approaches to reduce facility-acquired pressure ulcers<br />

• Case studies, case series, review articles, and original research reports focusing on topical therapies for pressure<br />

ulcers, vascular ulcers, or neuropathic (diabetic foot) ulcers<br />

• Original research reports focusing on the histologic and clinical effects of negative pressure wound therapy