Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-Century Europe - Corvinus Library ...

Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-Century Europe - Corvinus Library ...

Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-Century Europe - Corvinus Library ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

1<br />

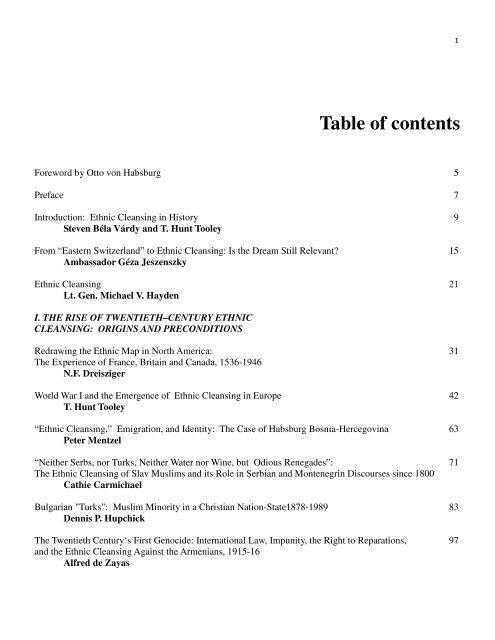

Table of contents<br />

Foreword by Otto von Habsburg 5<br />

Preface 7<br />

Introduction: <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> History 9<br />

Steven Béla Várdy and T. Hunt Tooley<br />

From “Eastern Switzerland” to <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong>: Is the Dream Still Relevant 15<br />

Ambassador Géza Jeszenszky<br />

<strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong> 21<br />

Lt. Gen. Michael V. Hayden<br />

I. THE RISE OF TWENTIETH–CENTURY ETHNIC<br />

CLEANSING: ORIGINS AND PRECONDITIONS<br />

Redraw<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>Ethnic</strong> Map <strong>in</strong> North America: 31<br />

The Experience of France, Brita<strong>in</strong> and Canada, 1536-1946<br />

N.F. Dreisziger<br />

World War I and the Emergence of <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Europe</strong> 42<br />

T. Hunt Tooley<br />

“<strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong>,” Emigration, and Identity: The Case of Habsburg Bosnia-Hercegov<strong>in</strong>a 63<br />

Peter Mentzel<br />

“Neither Serbs, nor Turks, Neither Water nor W<strong>in</strong>e, but Odious Renegades”: 71<br />

The <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong> of Slav Muslims and its Role <strong>in</strong> Serbian and Montenegr<strong>in</strong> Discourses s<strong>in</strong>ce 1800<br />

Cathie Carmichael<br />

Bulgarian "Turks": Muslim M<strong>in</strong>ority <strong>in</strong> a Christian Nation-State1878-1989 83<br />

Dennis P. Hupchick<br />

The <strong>Twentieth</strong> <strong>Century</strong>‘s First Genocide: International Law, Impunity, the Right to Reparations, 97<br />

and the <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Aga<strong>in</strong>st the Armenians, 1915-16<br />

Alfred de Zayas

2<br />

<strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Greek-Turkish Conflicts from the Balkan Wars through the Treaty of 112<br />

Lausanne: Identify<strong>in</strong>g and Def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong><br />

Ben Lieberman<br />

Consequences of Population Transfers: The 1923 Case of Greece and Turkey 122<br />

Eleni Eleftheriou<br />

<strong>Ethnic</strong> Heterogeneity, Cultural Homogenization, and State Policy <strong>in</strong> the Interwar Balkans 135<br />

Victor Roudometof<br />

II. THE ETHNIC CLEANSING OF GERMANS DURING<br />

AND AFTER WORLD WAR II<br />

Anglo-American Responsibility for the Expulsion of the Germans 1944-48 147<br />

Alfred de Zayas<br />

The London Czech Government and the Orig<strong>in</strong>s of the Expulsion of the Sudeten Germans 157<br />

Christopher Kopper<br />

Escap<strong>in</strong>g History: The Expulsion of the Sudeten Germans as a Leitmotif <strong>in</strong> German-Czech Relations 164<br />

Scott Brunstetter<br />

Polish-speak<strong>in</strong>g Germans and the <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong> of Germany East of Oder-Neisse 172<br />

Richard Blanke<br />

<strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> Upper Silesia, 1944-1951 180<br />

Tomasz Kamusella<br />

Reshap<strong>in</strong>g the Free City: Cleansed Memory <strong>in</strong> Danzig/ Gdańsk, 1939-1952 192<br />

Elizabeth Morrow Clark<br />

Cleansed Memory: The New Polish Wrocław/Breslau and the Expulsion of the Germans 206<br />

Gregor Thum<br />

Yugoslavia’s First <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong>: The Expulsion of the Danubian Germans, 1944-1946 221<br />

John R. Sch<strong>in</strong>dler<br />

The Expulsion of the Germans from Hungary after World War II 229<br />

János Angi<br />

The Deportation of <strong>Ethnic</strong> Germans from Romania to the Soviet Union, 1945-1949 238<br />

Nicolae Harsányi<br />

III. THE AFTEREFFECTS OF ETHNIC CLEANSING

3<br />

IN THE WAKE OF WORLD WAR II<br />

The Isolationist as Interventionist: Senator William Langer on the Subject of <strong>Ethnic</strong> 244<br />

<strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, March 29, 1946<br />

Charles M. Barber<br />

A House Divided: The Catholic Church and the Tensions 263<br />

between Refugees-Expellees and West Germans <strong>in</strong> the Postwar Era<br />

Frank Buscher<br />

The United States and the Refusal to Feed German Civilians after World War II 274<br />

Richard Dom<strong>in</strong>ic Wiggers<br />

The German Expellees and <strong>Europe</strong>an Values 289<br />

Emil Nagengast<br />

<strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong> and Collective Punishment: The Soviet Policy Towards Prisoners of War 303<br />

and Civilian Internees <strong>in</strong> the Carpathian Bas<strong>in</strong><br />

Tamás Stark<br />

Forgotten Victims of World War II: Hungarian Women <strong>in</strong> Soviet Forced Labor Camps 312<br />

Agnes Huszár Várdy<br />

Revolution and <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> Western Ukra<strong>in</strong>e: The OUN-UPA Assault aga<strong>in</strong>st 320<br />

Polish Settlements <strong>in</strong> Volhynia and Eastern Galicia, 1943-1944<br />

Alexander V. Prus<strong>in</strong><br />

The Deportation and <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong> of the Crimean Tatars 331<br />

Brian Glyn Williams<br />

<strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> Slovakia: The Plight of the Hungarian M<strong>in</strong>ority 345<br />

Edward Chászár<br />

The Hungarian-Slovak Population Exchange and Forced Resettlement <strong>in</strong> 1947 349<br />

Róbert Barta<br />

The Fate of Hungarians <strong>in</strong> Yugoslavia: Genocide, Ethnocide or <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong> 355<br />

Andrew Ludányi<br />

IV. SURVIVAL AND MEMORY: VERTREIBUNG<br />

A Survivor's Report 369<br />

Karl Hausner<br />

The Day I Will Never Forget 376<br />

Herm<strong>in</strong>e Hausner

4<br />

Exceptional Bonds: Revenge and Reconciliation <strong>in</strong> Potulice, Poland, 1945 and 1998 378<br />

Martha Kent<br />

Remarks by a Survivor 386<br />

Erich A. Helfert<br />

Recaptur<strong>in</strong>g the Spirit of Nuremberg: Published and Unpublished Sources on 389<br />

the Danube Swabians of Yugoslavia<br />

Raymond Lohne<br />

<strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong> and the Carpathian-Germans of Slovakia 394<br />

Andreas Roland Wesserle<br />

V. ETHNIC CLEANSING AND ITS BROADER IMPLICATIONS IN THE LAST THIRD<br />

OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY<br />

Systematic Policies of Forced Assimilation Aga<strong>in</strong>st Rumania’s Hungarian M<strong>in</strong>ority, 1965-1989 405<br />

László Hámos<br />

<strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Former Yugoslavia <strong>in</strong> the 1990s: A Euphemism for Genocide 417<br />

Klejda Mulaj<br />

Critique of the Concept of "<strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong>": The Case of Yugoslavia 428<br />

Robert H. Whealey<br />

Recent Developments <strong>in</strong> the Law of Genocide and Implications for Kosovo 438<br />

John Cerone<br />

The Shift<strong>in</strong>g Interpretation of the Term "<strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong>" <strong>in</strong> Central and Eastern <strong>Europe</strong> 446<br />

János Mazsu<br />

The Evolv<strong>in</strong>g Def<strong>in</strong>itions of IDPs and L<strong>in</strong>ks to <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Europe</strong> 454<br />

Gabriel S. Pelláthy<br />

Long-Term Consequences of Forced Population Transfers: Institutionalized <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong> as 465<br />

the Road to New (In-) Stability A <strong>Europe</strong>an Perspective<br />

Stefan Wolff<br />

<strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong> 1945 and Today: Observations on Its Illegality and Implications 474<br />

Alfred de Zayas<br />

Documentary Appendix 485<br />

Contributors 486<br />

List of Donors 496

5<br />

Foreword<br />

E<br />

thnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g has been part of human history ever s<strong>in</strong>ce classical times (witness the Babylonian<br />

Captivity of the Jews <strong>in</strong> the sixth century B.C.), but it did not become a commonly applied method of<br />

mass persecution until the twentieth century. Not until the century of Hitler and Stal<strong>in</strong> were tens of millions<br />

of people uprooted and forcibly ejected from their ancient homelands. This mass phenomenon affected many<br />

diverse nationalities and religious groups, among them the Armenians, Greeks, Turks, Hungarians, Jews,<br />

Germans, Croats, Serbians, Bosnians, and Crimean Tatars, as well as many others.<br />

These groups all suffered because of the misdirected ideologies of Nazism, Communism, and national<br />

chauv<strong>in</strong>ism. In terms of numbers, however, no one was more affected than the Germans, who had to witness<br />

the expulsion of fifteen to seventeen million of their co-nationalists from the lands which they had settled,<br />

tilled, and cultivated for many centuries. These <strong>in</strong>volved the Germans of former eastern Germany (now part<br />

of Poland and Russia), the Baltic countries, as well as the lands of the former Habsburg Empire. The latter<br />

<strong>in</strong>cluded the Sudeten Germans and the Zipsers of short-lived Czechoslovakia, the Saxons of Transylvania,<br />

the Danubian Swabians of Hungary and former Yugoslavia, as well as various other scattered German ethnic<br />

islands throughout Eastern <strong>Europe</strong>.<br />

I agree with President George W. Bush, who stated that "<strong>Ethnic</strong> cleans<strong>in</strong>g is a crime aga<strong>in</strong>st humanity,<br />

regardless of who does it to whom." I also agree with the United Nations Draft Declaration on Population<br />

Transfer, which states that "Every person has the right to rema<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> peace, security and dignity <strong>in</strong> one's home,<br />

or one's land and <strong>in</strong> one's country." It is this basic human right that has been grossly violated by those<br />

responsible for the expulsion of the Germans, Hungarians, Greeks, Armenians, and many others from their<br />

ancient homelands. And while much of this cannot be undone, the enormity of this crime should be<br />

recognized and acknowledged. The world should also learn about these violations of the basic human rights<br />

of many millions; if for no other reason, then to prevent any future expulsions on such a horrendous scale.<br />

I applaud the editors of this book, and the authors of the enclosed studies, for tak<strong>in</strong>g the effort to make the<br />

world aware of the suffer<strong>in</strong>g of many tens of millions of forcibly displaced <strong>in</strong>nocent people.<br />

OTTO VON HABSBURG

6<br />

<strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>Twentieth</strong>-<strong>Century</strong> <strong>Europe</strong><br />

Editors:<br />

Steven Béla Várdy<br />

Duquesne University<br />

and<br />

T. Hunt Tooly<br />

Aust<strong>in</strong> College<br />

Associate Editor:<br />

Agnes Huszár Várdy<br />

Robert Morris University<br />

Foreword<br />

Otto von Habsburg<br />

Paneuropa-Union<br />

SOCIAL SCIENCE MONOGRAPHS, BOULDER<br />

DISTRIBUTED BY COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS, NEW YORK<br />

2003<br />

Copyright © by Stephen Béla Várdy<br />

ISBN 0-88033-995-0<br />

LCCB 2003102445<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ted <strong>in</strong> the United States of America

7<br />

Preface<br />

T<br />

his book is the result of the Conference on <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Twentieth</strong>-<strong>Century</strong> <strong>Europe</strong> at Duquesne<br />

University (Thirty-Fourth Annual Duquesne University History Forum, held November 16-18, 2000).<br />

The Conference was cosponsored by the Institute for German-American Relations [IGAR] and Aust<strong>in</strong><br />

College (Sherman, Texas). F<strong>in</strong>ancially the conference was underwritten by grants from Duquesne University<br />

and Aust<strong>in</strong> College, with additional fund<strong>in</strong>g by IGAR. The latter Institute is also responsible for the partial<br />

subsidy for the publication of this book <strong>in</strong> Columbia University Press's East <strong>Europe</strong>an Monographs Series.<br />

The three-day conference attracted about sixty scholars and survivors of ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g from seven<br />

different countries, who presented a total of forty-eight papers. Most of these papers have found their way<br />

<strong>in</strong>to the present volume.<br />

The conference also hosted two keynote speakers: Lieutenant-General Michael Hayden, Director of the<br />

National Security Agency (a graduate of Duquesne University), and Dr. Géza Jeszenszky, Hungary's<br />

Ambassador to the United States (as well as a published scholar-historian). The essays stemm<strong>in</strong>g from their<br />

conference addresses are pr<strong>in</strong>ted at the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g of this volume.<br />

The organizers of this conference were Professor Steven Béla Várdy (Director, Duquesne University<br />

History Forum) and Professor T. Hunt Tooley (Aust<strong>in</strong> College). We were supported by Professor Agnes<br />

Huszár Várdy (Robert Morris University) and Dr. Marianne Bouvier (Executive Director, IGAR). The first<br />

three of these also undertook the task of edit<strong>in</strong>g this volume, with Professor Tooley assum<strong>in</strong>g the additional<br />

burden of formatt<strong>in</strong>g the manuscript <strong>in</strong>to a camera-ready copy.<br />

The papers collected <strong>in</strong> this volume represent more than the sum of what the contributors brought with<br />

them to the conference. It seemed to approach the scholarly ideal of a balance between discussion and<br />

presentation. The topic encompassed a vast array of case studies, behaviors, orig<strong>in</strong>s, and patterns, but it<br />

rema<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> the end highly focused. The presenters, discussants, and audience were engaged, perceptive, and<br />

lively. We were historians <strong>in</strong> the majority but profited from the presence of a wide range of specialists <strong>in</strong><br />

other fields as well as many students and "laymen," many of them with personal or family histories <strong>in</strong>volved<br />

<strong>in</strong> the events under discussion. As the conference progressed, we worked quite consciously to def<strong>in</strong>e and<br />

ref<strong>in</strong>e the topic under discussion, both <strong>in</strong> formal sessions and countless <strong>in</strong>formal talks. This challeng<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

stimulat<strong>in</strong>g atmsophere led most of the presenters to work and rework their papers <strong>in</strong> the follow<strong>in</strong>g months.<br />

The result is a measure of coherence and collective purpose <strong>in</strong> this volume which is gratify<strong>in</strong>g to the editors.<br />

It is a pleasure to thank publicly those persons and <strong>in</strong>stitutions who contributed both to the Conference on<br />

<strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Twentieth</strong>-<strong>Century</strong> <strong>Europe</strong> and to the book itself. We would like to thank Paula Jonse,<br />

formerly Humanities Division Adm<strong>in</strong>– istrative Assistant at Aust<strong>in</strong> College, who was of great assistance at<br />

many stages of this project. The Information Technology office of Aust<strong>in</strong> College provided much support <strong>in</strong><br />

the production of this book. Karen Tooley helped <strong>in</strong> the organizational phase of the conference and also<br />

worked on the preparation of the manuscript. Special thanks is also due to Martha Kent and Alfred de Zayas,<br />

who not only contributed articles to the book but also helped <strong>in</strong> many other ways both to br<strong>in</strong>g this effort to<br />

its conclusion and to improve the quality of its end result.

8<br />

The two coeditors and the associate editor would like to thank their respective <strong>in</strong>stitutions for the support<br />

they have received. The hospitality and generosity of Duquesne University and <strong>in</strong> particular of the Duquesne<br />

Department of History played a crucial role <strong>in</strong> creat<strong>in</strong>g a comfortable and collegial venue for the meet<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

We are grateful as well to the Institute for German-American Relations for cosponsor<strong>in</strong>g this conference and<br />

the result<strong>in</strong>g volume. The coeditors would also like to thank Professor Stephen Fischer-Galati for publish<strong>in</strong>g<br />

this work <strong>in</strong> Columbia University Press's <strong>in</strong>ternationally known East <strong>Europe</strong>an Monographs Series.<br />

THE EDITORS<br />

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and Sherman, Texas<br />

December 2002

9<br />

Introduction<br />

<strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> History<br />

STEVEN BÉLA VÁRDY and T. HUNT TOOLEY<br />

A<br />

s po<strong>in</strong>ted out by José Ortega y Gasset (1883-1955) <strong>in</strong> his epoch-mak<strong>in</strong>g work The Revolt of the Masses<br />

(1929) 1 , dur<strong>in</strong>g the n<strong>in</strong>eteenth and twentieth centuries the Western World had witnessed the emergence of the<br />

common populace to a position of economic and political <strong>in</strong>fluence <strong>in</strong> human society. Be<strong>in</strong>g essentially of<br />

republican sympathies, and sympathiz<strong>in</strong>g with the exploited underclasses of Western Civilization, Ortega readily<br />

recognized the positive implications of this mass phenomenon for the people <strong>in</strong> general. At the same time,<br />

however, he feared that this ascendance of the uncouth, boorish, and unwashed masses might lead to civilization's<br />

relapse <strong>in</strong>to a new form of barbarism. He was conv<strong>in</strong>ced of the "essential <strong>in</strong>equality of human be<strong>in</strong>gs," and<br />

consequently he believed <strong>in</strong> the unique role of the "<strong>in</strong>tellectual elites" <strong>in</strong> the shap<strong>in</strong>g of history. 2<br />

As a disciple of the Geistesgeschichte view of human evolution, Ortega was conv<strong>in</strong>ced of the primacy of<br />

spiritual and <strong>in</strong>tellectual factors over economic and material forces <strong>in</strong> historical evolution. Given these<br />

convictions, he feared that the emergence of a mass society—dom<strong>in</strong>ated, as it was, by economic and<br />

material considerations—would result <strong>in</strong> the reemergence of barbarism on a mass scale.<br />

That Ortega's fears were partially justified can hardly be doubted <strong>in</strong> light of the mass exterm<strong>in</strong>ations<br />

witnessed by several twentieth-century generations of human be<strong>in</strong>gs. As we all know, <strong>in</strong> the second quarter<br />

of the past century six million Jews and many thousands of non-Jewish people were exterm<strong>in</strong>ated at the<br />

orders of a lowly corporal turned <strong>in</strong>to the unquestioned leader of Germany (Hitler). At the same time, forty<br />

to fifty million <strong>in</strong>nocent human be<strong>in</strong>gs fell victim to the twisted m<strong>in</strong>d of a Caucasian brigand turned <strong>in</strong>to the<br />

"<strong>in</strong>fallible leader" of the homeland of socialism (Stal<strong>in</strong>). Moreover, s<strong>in</strong>ce the end of World War II, the world<br />

has also stood witness to mass kill<strong>in</strong>gs, expulsions, and genocides <strong>in</strong> such widely scattered regions of the<br />

world as Cambodia <strong>in</strong> Southeast Asia, Rwanda <strong>in</strong> Central Africa, and <strong>in</strong> Bosnia <strong>in</strong> former Yugoslavia.<br />

In look<strong>in</strong>g at these terror actions aga<strong>in</strong>st an ethnic group, religious denom<strong>in</strong>ation, or nationality—be<br />

these mass expulsions, partial exterm<strong>in</strong>ations, or genocides—we are often confused how to categorize them.<br />

Scholars and publicists are particularly confounded at the dist<strong>in</strong>ctions or alleged dist<strong>in</strong>ctions between<br />

"genocide" and "ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g." The first of these terms came <strong>in</strong>to common use <strong>in</strong> conjunction with the<br />

Jewish Holocaust of the World War II period, while the second term ga<strong>in</strong>ed currency <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>ter-ethnic<br />

struggles of Bosnia dur<strong>in</strong>g the early 1990s.<br />

This obfuscation and bewilderment became even more pronounced recently, particularly <strong>in</strong> consequence<br />

of the belated application of one or another of these terms to such earlier events as the so-called "Armenian<br />

1 La rebellion de las masas (1929; English translation, 1932).<br />

2 Academic American Encyclopedia (Pr<strong>in</strong>ceton, 1980), 14: 449.

10<br />

Holocaust" of 1915, 3 and the various "ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>gs" that took place <strong>in</strong> wake of the two world wars and<br />

the simultaneous changes <strong>in</strong> political borders. We know that most ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong>volve some physical<br />

abuse and some number of <strong>in</strong>tended or un<strong>in</strong>tended deaths. We also know that none of these so-called<br />

Holocausts were able to exterm<strong>in</strong>ate all members of a particular group. Consequently, <strong>in</strong> actual practice or<br />

application, the mean<strong>in</strong>g of these two terms often tend to merge. At times it is really difficult to differentiate<br />

between the two, particularly <strong>in</strong> light of the fact that the application of violence <strong>in</strong> some ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

often reaches the po<strong>in</strong>t of mass kill<strong>in</strong>gs, thus turn<strong>in</strong>g that event <strong>in</strong>to a potential genocide.<br />

While we recognized the difficulty of dist<strong>in</strong>guish<strong>in</strong>g between these two phenomena, <strong>in</strong> the conference<br />

upon which this book is based we tried to limit our attention to the historical events that could clearly be<br />

classified as „ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g." We were able to do this, because we equated "genocide" with the Jewish<br />

Holocaust, which was def<strong>in</strong>itely a case of ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g on a mass scale, but which was also more. We<br />

tried to start with a def<strong>in</strong>ition of "genocide" as "the planned, directed, and systematic exterm<strong>in</strong>ation of a<br />

national or ethnic group." At the same time our work<strong>in</strong>g def<strong>in</strong>ition of "ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g" was more focused<br />

on the process of remov<strong>in</strong>g people from a given territory: "the mass removal of a targeted population from a<br />

given territory, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g forced population exchanges of peoples from their orig<strong>in</strong>al homelands as well as<br />

other means." We did this <strong>in</strong> part because had we <strong>in</strong>cluded "genocide" as a topic of our conference, <strong>in</strong> the<br />

sense of the National Socialist war aga<strong>in</strong>st the Jews, much of the attention of the participants would have<br />

been taken up by the Holocaust. There is, of course, hardly a more significant twentieth-century historical<br />

topic than Hitler's efforts to exterm<strong>in</strong>ate the Jews. But precisely for that reason, dur<strong>in</strong>g the past half a<br />

century, it has been <strong>in</strong> the focus and awareness of hundreds of scholars, who have produced thousands of<br />

volumes on this topic. Not so the topic of "ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g," which has largely been ignored until the<br />

Bosnian crisis of the 1990s. 4 In any event, most of the presentations at the Conference on <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>Twentieth</strong>–<strong>Century</strong> <strong>Europe</strong> at Duquesne University, as will be seen, worked to exam<strong>in</strong>e and ref<strong>in</strong>e the<br />

def<strong>in</strong>ition of the phenomenon of ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g. At the conference itself, the participants devoted much<br />

time and energy to discussions of def<strong>in</strong>itions. The results will be seen <strong>in</strong> the expanded and ref<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

conference papers which make up the chapters of this book.<br />

Although the term "ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g" has come <strong>in</strong>to common usage only s<strong>in</strong>ce the Bosnian conflict, the<br />

practice itself is almost as old as humanity itself. It reaches back to ancient times. An early example of such<br />

an ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g was the "Babylonian Captivity" of the Jews <strong>in</strong> the sixth century B.C. (from 586 to 538<br />

B.C.). After captur<strong>in</strong>g Jerusalem <strong>in</strong> 586 B.C., K<strong>in</strong>g Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 605-561 B.C.) of Babylonia<br />

proceeded to deport the Judeans to his own k<strong>in</strong>gdom, and <strong>in</strong> this way he "cleansed" the future Holy Land of<br />

most of its native <strong>in</strong>habitants.<br />

Similar ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>gs took place <strong>in</strong> the period of the so-called "barbarian <strong>in</strong>vasions" of the fourth<br />

through the sixth centuries, when large, nation-like tribes—Germans, Slavs, and various Turkic peoples—<br />

3 The ex post facto application of the term “Holocaust” or “genocide” to the forced transfer of many of Ottoman Turkey’s Armenian population from Turkish<br />

Armenia <strong>in</strong> the north to Cilicia or Lesser Armenia <strong>in</strong> the south is a hotly debated issue. Many scholars view it as a population transfer that should be called<br />

“ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g.” Others, emphasiz<strong>in</strong>g the large percentage of the transferees who died, prefer to classify it as a “Holocaust.” For the Armenian side of the<br />

story see Robert Melson, Revolution and Genocide: On the Orig<strong>in</strong>s of the Armenian Genocide and Holocaust (Chicago, London, 1992); Vahakn N. Dadrian,<br />

The History of the Armenian Genocide: <strong>Ethnic</strong> Conflict from the Balkans to Anatolia to the Caucasus (Providence, Oxford, 1995); and Vahakn N. Dadrian,<br />

“The Role of Turkish Physicians <strong>in</strong> the World War I Genocide of Ottoman Armenians,” Holocaust and Genocide Studies 1 (Autumn 1986): 169-192. For the<br />

Turkish and American side of that story see Mim Kemal Öke, The Armenian Question, 1914-1923 (Oxford, 1988) and Stanford J. Shaw and Ezel Kural Shaw,<br />

History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey (Cambridge, 1976-1977), 2: 314-317. See also Ronald Suny, “Reth<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g the Unth<strong>in</strong>kable: Toward an<br />

Understand<strong>in</strong>g of the Armenian Genocide,” <strong>in</strong> Ronald Grigor Suny, Look<strong>in</strong>g Toward Ararat: Armenia <strong>in</strong> Modern History (Bloom<strong>in</strong>gton, Ind., 1993), 94-115.<br />

4 On ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> general see Andrew Bell-Fialkoff, “A Brief History of <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong>,” Foreign Affairs 72 (Summer 1993):110-120; Andrew Bell-<br />

Fialkoff, <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong> (New York, 1996); Dražen Petrović, “<strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong>: An Attempt at Methodology,” <strong>Europe</strong>an Journal of International Law 5<br />

(1994): 342-359; Robert M. Hayden, “Sch<strong>in</strong>dler’s Fate: Genocide, <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, and Population Transfer,” Slavic Review 55 (W<strong>in</strong>ter 1996): 727-748;<br />

Jennifer Jackson Preece, ”<strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong> as an Instrument of Nation-State Creation: Chang<strong>in</strong>g State Practices and Evolv<strong>in</strong>g Legal Norms,” Human<br />

Rights Quarterly, 20 (1998): 817-842; Norman M. Naimark, <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Twentieth</strong> <strong>Century</strong> <strong>Europe</strong> [The Donald W. Treadgold Papers, no. 19]<br />

(Seattle, 2000); and Norman Naimark, Fires of Hatred: <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Twentieth</strong>–<strong>Century</strong> <strong>Europe</strong> (Cambridge, Mass., 2001).

moved back and forth between Western and Eastern <strong>Europe</strong>, and even Central Asia. They forcibly displaced<br />

one another, and <strong>in</strong> this way reshaped the ethnic map of the <strong>Europe</strong>an cont<strong>in</strong>ent. This so-called<br />

Völkerwanderung ("wander<strong>in</strong>g of nations")—which, <strong>in</strong> some <strong>in</strong>stances, stretched <strong>in</strong>to the late Middle Ages—brought<br />

such peoples as the Huns, Avars, Bulgars, Magyars, Pechenegs, and Cumans <strong>in</strong>to the very heart<br />

of <strong>Europe</strong>. Its aftereffects were felt as late as the thirteenth century, when the Mongols or Tatars <strong>in</strong>vaded<br />

<strong>Europe</strong>, conquered the eastern half of the cont<strong>in</strong>ent, and then settled down there to rule over the East Slavs<br />

for several centuries.<br />

Although this process of forcible relocations has been practiced for millennia, ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g as an<br />

official policy did not come <strong>in</strong>to be<strong>in</strong>g until more recent times. In the Western world, large-scale forcible<br />

relocation of a specified "people' was <strong>in</strong>troduced <strong>in</strong> the early n<strong>in</strong>eteenth century United States, as the official<br />

policy of the United State government. Informally, scores of Indian tribes had "emigrated" from their lands<br />

as a result of <strong>Europe</strong>an pressure, at times escap<strong>in</strong>g from direct violence by <strong>Europe</strong>an settlers, at times<br />

look<strong>in</strong>g for food, at times be<strong>in</strong>g pushed by other native groups react<strong>in</strong>g to direct pressure from <strong>Europe</strong>an<br />

settlers. The process of removal became standardized federal policy <strong>in</strong> 1830, when Congress passed the<br />

"Indian Removal Act." Some of the saddest manifestations of this policy, implemented dur<strong>in</strong>g Andrew<br />

Jackson's presidency (1829-1837), was the decimation and expulsion of the affiliated Sac and the Fox tribes<br />

from the Upper Mississippi region (Black Hawk War of 1832), the forcible relocation of the Creek, Choctaw,<br />

Chickasaw, and Cherokee nations from the Old Southwest to Indian Territory (Trail of Tears, 1838-1839),<br />

and the similar expulsion of the Sem<strong>in</strong>ole Indians from Florida to future Oklahoma (Second Sem<strong>in</strong>ole War,<br />

1835-1843). The process of forcible removal to reservations was repeated countless times from the 1820s<br />

through the 1880s. 5<br />

In <strong>Europe</strong> itself, the rise of "national" awareness at the end of the eighteenth century spread across<br />

<strong>Europe</strong> from West to East. By the middle of the century, some nationalist leaders and th<strong>in</strong>kers were already<br />

th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> terms of an exclusivist doctr<strong>in</strong>e call<strong>in</strong>g for the "nation" to correspond with the "state," that is, to<br />

make political borders correspond with ethnic or l<strong>in</strong>guistic borders. S<strong>in</strong>ce precise ethnic boundaries hardly<br />

existed anywhere <strong>in</strong> <strong>Europe</strong>, any plann<strong>in</strong>g for such new "nations" necessitated th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g about what to do<br />

with <strong>in</strong>dividuals from other ethnic groups who were left on the <strong>in</strong>side of someone else's national state.<br />

Carry<strong>in</strong>g out such exclusivist ethnic nationalism was approached <strong>in</strong> a number of ways <strong>in</strong> various sett<strong>in</strong>gs,<br />

and a number of small states moved toward policies of ethnic exclusion <strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eteenth century. It was on<br />

the peripheries of the great <strong>Europe</strong>an empires (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g especially the Ottoman Empire) that a sharp-edged,<br />

ethnicity-oriented policy led to a variety of policies of forced assimilation, expropriation of property,<br />

violence, and <strong>in</strong> several cases, mass kill<strong>in</strong>g. 6<br />

Follow<strong>in</strong>g the destruction or mutilation of such established <strong>Europe</strong>an empires as Austria-Hungary,<br />

Ottoman Turkey, Russia, and Germany <strong>in</strong> wake of World War I, and the simultaneous creation of nearly a<br />

dozen allegedly national, but <strong>in</strong> fact mostly mult<strong>in</strong>ational small states, the policy of ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g was<br />

<strong>in</strong>troduced <strong>in</strong>to modern <strong>Europe</strong> as a regular policy and <strong>in</strong> a certa<strong>in</strong> sense "legitimized." The newly created,<br />

reestablished, or radically enlarged "successor states"—particularly Czecho- slovakia, Yugoslavia, and<br />

Romania <strong>in</strong> the center; Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey <strong>in</strong> the south; and to a lesser degree Poland and<br />

Lithuania <strong>in</strong> the north—expelled hundreds of thousands of m<strong>in</strong>ority <strong>in</strong>habitants from their newly acquired or<br />

11<br />

5 See Francis Paul Prucha, The Sword of the Republic: The United States Army on the Frontier, 1783-1846 (L<strong>in</strong>coln, 1987); Black Hawk, An Autobiography<br />

(1833 ed.), ed. Donald Jackson (Urbana, Ill., 1990); Ronald N. Satz. American Indian Policy <strong>in</strong> the Jacksonian Era (L<strong>in</strong>coln, 1975); and Grant Foreman,<br />

Indian Removal: The Emigration of the Five Civilized Tribes of Indians (Norman, Okl., 1986).<br />

6 On the rise of this hard-shelled, ethnic nationalism <strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eteenth century, see the excellent anthology, John Hutch<strong>in</strong>son and Anthony Smith, eds.,<br />

Nationalism (Oxford, 1994), esp. 160-195.

12<br />

restructured territories. 7 Many of these expulsions also <strong>in</strong>volved military encounters among several of these<br />

nations and newly created states. The most violent of these encounters was the Greek-Turkish War of 1920-<br />

1923, which resulted <strong>in</strong> a forced population exchange that compelled 1.3 million Greeks to leave Anatolia,<br />

and 350,000 Turks to evacuate Greek-controlled Thrace. 8<br />

The climax of this policy of ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g came <strong>in</strong> the wake of World War II, when—based on the<br />

erroneous pr<strong>in</strong>ciples of collective guilt and collective punishment—perhaps as many as sixteen million<br />

Germans were compelled to leave their ancient homelands <strong>in</strong> East-Central and Southeastern <strong>Europe</strong>. At the<br />

Yalta and Potsdam Conferences, the leaders of the victorious great powers agreed to truncate Germany and<br />

transfer Eastern Germany's ethnic German population to the rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g portions of the country. They<br />

likewise agreed to expel the 3.5 million Sudeten Germans from the mounta<strong>in</strong>ous frontier regions of Bohemia<br />

and Moravia (the Czech state)—a region that these Germans had <strong>in</strong>habited for over seven centuries. A<br />

similar policy of expulsion was also applied, although less str<strong>in</strong>gently, to the smaller German ethnic<br />

communities of Hungary, Romania, and Yugoslavia. All <strong>in</strong> all, 16.5 million Germans may have fallen victim<br />

to this officially sponsored policy of ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g. 9<br />

Although the Germans were the primary victims of this new policy, the Hungarians were also been<br />

subjected to it, especially <strong>in</strong> Eduard Beneš's reconstituted Czechoslovakia. In the course of 1945-1946, over<br />

200,000 thousand of them were driven across the Danube, most of them <strong>in</strong> the middle of the w<strong>in</strong>ter and<br />

without proper cloth<strong>in</strong>g and provisions. This so-called "Košicky Program"—which became the<br />

Czechoslovak government's official policy vis-à-vis the Hungarians 10 —was a smaller version of the "ethnic<br />

cleans<strong>in</strong>g" that had cleared Czechoslovakia of its German citizens. It is to the credit of Václav Havel, the<br />

President of the Czech Republic, that <strong>in</strong> his former capacity as the last President of Czechoslovakia he<br />

acknowledged the immorality of the policy.<br />

The most recent manifestations of ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g—at least as far as Central and Southeastern <strong>Europe</strong><br />

are concerned—were cases which were experienced recently by the former Yugoslav prov<strong>in</strong>ces of Bosnia<br />

and Kosovo. 11 These were the actions that popularized the expression "ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g" and gave it a<br />

def<strong>in</strong>ition as dist<strong>in</strong>ct from the term "genocide," a term which, as seen above, implies not only the<br />

displacement, but also the mass exterm<strong>in</strong>ation of a targeted ethnic group.<br />

The papers presented at the "Conference on <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong>" at Duquesne University (November 16-<br />

18, 2000) survey much of the process of forced population exchanges <strong>in</strong> twentieth-century <strong>Europe</strong>. It seems<br />

a strange twist of fate that this first-ever conference on ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g should have taken place at an<br />

<strong>in</strong>stitution, which itself came <strong>in</strong>to be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> consequence of a k<strong>in</strong>d of "ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g." And that was Otto<br />

7 See the classic work by C. A. Macartney, Hungary and Her Successors: The Treaty of Trianon and its Consequences, 1919-1937 (Oxford, 1937) [new ed.<br />

1968]; István I. Mócsy, The Effects of World War I: The Uprooted: Hungarian Refugees and their Impact on Hungarian Domestic Politics, 1918-1921<br />

(Boulder and New York, 1983). One of the most comprehensive of the relevant scholarly volumes, which <strong>in</strong>cludes studies by over thirty scholars, is B. K.<br />

Király, P. Pastor, and I. Sanders, eds., War and Society <strong>in</strong> East Central <strong>Europe</strong>: Essays on World War I: A Case Study of Trianon (New York, 1982).<br />

8 Cf. Arnold J. Toynbee, The Western Question <strong>in</strong> Greece and Turkey: A Study <strong>in</strong> the Contact of Civilizations, 2nd ed. (London, Bombay, 1923); Stephen<br />

Ladas, The Exchange of M<strong>in</strong>orities: Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey (New York, 1932); Dimitri Pentzopoulos, The Balkan Exchange of M<strong>in</strong>orities and its Impact<br />

upon Greece (Paris and the Hague, 1962).<br />

9 On the post-World War II expulsion of the Germans see especially Alfred M. de Zayas’s classic work, Nemesis at Potsdam. The Anglo-Americans and the<br />

Expulsion of the Germans, rev. ed. (London, Boston, 1979); see also Gerhard Ziemer, Deutscher Exodus: Vertreibung und E<strong>in</strong>gliederung von 15 Millionen<br />

Ostdeutschen (Stuttgart, 1973); Die Vertreibung der deutschen Bevölkerung aus der Tschechoslowakei, 2 vols. (Munich, 1984). He<strong>in</strong>z Nawratil, Vertreibungs-<br />

Verbrechen an Deutschen (Munich, 1987).<br />

10 Concern<strong>in</strong>g Hungarian expulsions and the fate of Hungarian m<strong>in</strong>orities <strong>in</strong> the surround<strong>in</strong>g “successor states” see Elemér Illyés, National M<strong>in</strong>orities <strong>in</strong><br />

Romania: Change <strong>in</strong> Transylvania (Boulder and New York, 1982); John Cadzow, Andrew Ludányi, and Louis J. Elteto (eds.) Transylvania: The Roots of<br />

<strong>Ethnic</strong> Conflict (Kent, Ohio, 1983); Stephen Borsody (ed.), The Hungarians: A Divided Nation (New Haven, 1988); and Raphael Vágó, The Grand Children<br />

of Trianon: Hungary and the Hungarian M<strong>in</strong>ority <strong>in</strong> the Communist States (Boulder and New York, 1989).<br />

11 Norman Cigar, Genocide <strong>in</strong> Bosnia: The Policy of “<strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong>” (College Station, 1995); and Christopher Bennet, “<strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> Former<br />

Yugoslavia,” <strong>in</strong> The <strong>Ethnic</strong>ity Reader: Nationalism, Multiculturalism and Migration, ed. Monserrat Guibernau and John Rex (Cambridge, 1997), 122-135.

von Bismarck's anti-Catholic crusade known as the Kulturkampf (1872-1878), which drove the Religious<br />

Order of the Holy Ghost out of Germany, and brought them to a hill <strong>in</strong> the middle of Pittsburgh,<br />

Pennsylvania, where <strong>in</strong> 1878 they founded an <strong>in</strong>stitution of higher learn<strong>in</strong>g, known today as Duquesne<br />

University.<br />

One of the primary functions of the Conference on <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Twentieth</strong>-<strong>Century</strong> <strong>Europe</strong> was to<br />

br<strong>in</strong>g to light the state of new research on the various episodes of ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> modern <strong>Europe</strong>. In<br />

do<strong>in</strong>g this, the organizers and contributors hoped to explore the historical and legal aspects of ethnic<br />

cleans<strong>in</strong>g and to look comparatively at the experiences of populations expelled and the process of ethnic<br />

cleans<strong>in</strong>g itself. Many commonalities emerged <strong>in</strong> the process of putt<strong>in</strong>g the conference together, and from<br />

these we developed a number of themes which seemed to be uppermost <strong>in</strong> the m<strong>in</strong>ds of those participat<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

We stated these before the conference as follows:<br />

1. Def<strong>in</strong>ition. What is ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g Should all cases of population transfer be conceptualized as<br />

the same phenomenon Has "ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g" been diluted <strong>in</strong> terms of mean<strong>in</strong>g Should we adopt<br />

another term<strong>in</strong>ology <strong>in</strong> deal<strong>in</strong>g with the varieties of forced transfers of populations<br />

2. Orig<strong>in</strong>s. <strong>Ethnic</strong> cleans<strong>in</strong>g has existed <strong>in</strong> some form from antiquity, but it has never been practiced<br />

with more variety or <strong>in</strong>tensity than <strong>in</strong> the twentieth century. Where do we look for the orig<strong>in</strong>s and<br />

roots of this outburst Nationalism State build<strong>in</strong>g Popular movements Economic conditions<br />

3. Consequences. Clearly, many twentieth-century politi– cal leaders have opted to engage <strong>in</strong> forced<br />

population transfers and related behaviors. Misery to those trans– ferred has been one result, and that<br />

should not <strong>in</strong> any way be m<strong>in</strong>imized. We should also ask, however: "What have been the long-term<br />

results"<br />

4. Processes. Look<strong>in</strong>g at many cases of ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g, how do the processes, carried out over the<br />

century and <strong>in</strong> many different regions, compare Can we see a con– t<strong>in</strong>uity Or do the cases of ethnic<br />

cleans<strong>in</strong>g tend to exhibit highly specific, or particular, characteristics centered around local conditions<br />

and history<br />

We tried to def<strong>in</strong>e our topic <strong>in</strong> such a way as to make it clear that the Holocaust would be a crucial and<br />

constant background consideration. Yet <strong>in</strong> a sense, our conference was an attempt to assess a particular<br />

historiography—the analysis of ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g—at a relatively early stage of development, while the<br />

scholarship on the Holocaust is not only enormously larger, but also more mature <strong>in</strong> a historiographical<br />

sense. 12 As one can see <strong>in</strong> the follow<strong>in</strong>g book, many conference participants drew on the historiography of<br />

the Holocaust for both analytical and comparative purposes, even as they focused on historical episodes that<br />

have been studied much less. Indeed, some of the episodes addressed <strong>in</strong> the follow<strong>in</strong>g articles are hardly<br />

known at all <strong>in</strong> the English-speak<strong>in</strong>g world, except among small groups of descendants of the "cleansed"<br />

people and a few scholars.<br />

Although the contributors to this book therefore approach some of these cases for almost the first time <strong>in</strong><br />

a scholarly way, we should make it clear that the long list of topics is <strong>in</strong> no way meant to be absolutely<br />

comprehensive. Numerous cases of ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> twentieth-century <strong>Europe</strong> are not represented here.<br />

Their absence, it must be said, is not due to any desire of the organizers of the conference and the editors of<br />

the book to exclude or suppress one case or another of the abhorrent practice of ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g. Our<br />

13<br />

12 For an <strong>in</strong>tensive <strong>in</strong>troduction to the historiography of the Holocaust, see Michael R. Marrus, The Holocaust <strong>in</strong> History (New York, 1987).

14<br />

treatment is limited <strong>in</strong> this sense by the practical reason that we were restricted to those scholars who<br />

answered the various calls for papers <strong>in</strong> the usual scholarly sources.<br />

In the end, participants <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong>dividuals from seven countries <strong>in</strong> two cont<strong>in</strong>ents. Most were<br />

historians, but many were political scientists, literary scholars, sociologists, and legal scholars. Presenters<br />

ranged from those still engaged <strong>in</strong> graduate study to scholars who have published many books <strong>in</strong> the field of<br />

<strong>Europe</strong>an history, law, and politics. Among the presenters were four survivors of ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g whom we<br />

asked to write explicitly about their own experiences.<br />

The articles <strong>in</strong>vestigate dozens of cases of ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the twentieth century. A number of<br />

contributors deal with ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the period of World War I, <strong>in</strong> particular those episodes aris<strong>in</strong>g from<br />

the clash between Greece and Turkey at the end of the war. The period of World War II gave full play to the<br />

deadly policies of Stal<strong>in</strong>ist Russia <strong>in</strong> the East and Hitler's Third Reich, as well as many cases which clearly<br />

spun off of these policies of ferocious ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g. Hence, contributors deal with ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g of<br />

Poles by Ukra<strong>in</strong>ians, Romanians by Russians, Germans by Titoist Yugoslavia, and others.<br />

The vast case of the ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g of Germans, the "Expulsion," forms an important part of the book.<br />

Fifteen contributors deal with the expulsions of Germans from East Central <strong>Europe</strong> from one standpo<strong>in</strong>t or<br />

another. This extensive share seems <strong>in</strong> no way out of place, s<strong>in</strong>ce the expulsion of sixteen million ethnic<br />

Germans from half a dozen <strong>Europe</strong>an countries, at a loss of over two million lives, constitutes an episode<br />

which surely merits attention but which has been neglected by all but a handful of historians. 13 The<br />

contemporaneous ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g of Hungarian populations, mentioned above, will be a familiar topic to<br />

even fewer readers.<br />

In deal<strong>in</strong>g with the history of post-Cold War ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the Balkans, contributors pay much<br />

attention to processes and patterns, but they also do much to explore concepts and def<strong>in</strong>itions. Multiple<br />

approaches to the complexities of the Balkans and the violence which has marked the dissolution of<br />

Yugoslavia prove most useful <strong>in</strong> conceptualiz<strong>in</strong>g as well as recount<strong>in</strong>g ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the region that<br />

seems to have named it.<br />

The studies of ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g which follow represent an earnest attempt to make sense of a terrible aspect<br />

of the twentieth century, a century whose reputation for barbarity, when viewed <strong>in</strong> total, goes beyond even<br />

the pessimistic vision of Ortega y Gasset. Record<strong>in</strong>g the erosion of <strong>in</strong>dvidual autonomy and dignity, the<br />

frequent lapse of the rule of law, and the blatant disregard of the ideals of justice long considered to be at the<br />

heart of the <strong>Europe</strong>an tradition does not tell the whole story. That story must also <strong>in</strong>clude the rise of a new<br />

set of barbarous practices and behaviors that ignored the pleas of <strong>in</strong>dividuals for a homeland, rejected the<br />

rights of <strong>in</strong>dividuals to their own property and the fruits of their labor, and <strong>in</strong> many cases denied the right of<br />

the targeted peoples to live.<br />

13 On the recent historical writ<strong>in</strong>g on the expulsions of Germans, see Alfred de Zayas, A Terrible Revenge: The <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong> of the East <strong>Europe</strong>an<br />

Germans, 1944-1950 (New York, 1993) (orig<strong>in</strong>ally published <strong>in</strong> Germany as Anmerkungen zur Vertreibung der Deutschen as dem Osten [Stuttgart, 1986]).<br />

Also of <strong>in</strong>terest is the special issue of Deutsche Studien devoted to "Flucht und Vertreibung der Ostdeutschen und ihre Integration"—see for an overview the<br />

<strong>in</strong>troduction by Gerhard Doliesen, "Der Umgang der deutschen und polnischen Gesellschaft mit der Vertreibung," Deutsche Studien 126/127 (1995): 105-<br />

110. The late 1990s saw <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> the topic grow <strong>in</strong> several directions. See, for example, Philipp Ther, Deutsche und polnische Vertriebene: Gesellschaft und<br />

Vertriebenenpolitik <strong>in</strong> der SBZ/DDR und <strong>in</strong> Polen 1945-1956 (Goett<strong>in</strong>gen, 1998); Mathias Beer, "Im Spannungsfeld von Politik und Zeitgeschichte: das<br />

Grossforschungsprojekt: 'Dokumentation der Vertreibung der Deutschen aus Ost-Mitteleuropa,'" Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 46 (1998); Detlef<br />

Brandes, Der Weg zur Vertreibung, 1938-1945: Pläne und Entscheidungen zum "Transfer" der Deutschen aus der Tschechoslowakei und aus Polen (Munich,<br />

2001); Philipp Ther and Ana Siljak, eds., Redraw<strong>in</strong>g Nations: <strong>Ethnic</strong> <strong>Cleans<strong>in</strong>g</strong> In East-Central <strong>Europe</strong>, 1944-1948 (New York, 2001). Norman Naimark has<br />

approached the German expulsions comparatively <strong>in</strong> Fires of Hatred.

15<br />

From “Eastern Switzerland” to <strong>Ethnic</strong> Cleas<strong>in</strong>g:<br />

Is the Dream Still Relevant<br />

GÉZA JESZENSZKY<br />

Hungarian Ambassador to the United States<br />

T<br />

en years ago, <strong>in</strong> the bliss of annus mirabilis, the term “ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g” was unknown. Today we devote<br />

a conference to that subject only to discover how many crim<strong>in</strong>al events <strong>in</strong> history may fall under that<br />

hideous category. While the organizers of the conference were wise <strong>in</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g out the difference between<br />

forced migration, population exchange, and mass exterm<strong>in</strong>ation aim<strong>in</strong>g at genocide, we haven’t yet adopted<br />

a def<strong>in</strong>ition of the term “ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g.” I would like to po<strong>in</strong>t out, however, that <strong>in</strong> my op<strong>in</strong>ion the term is<br />

worse than euphemistic; it is mislead<strong>in</strong>g. It has noth<strong>in</strong>g to do with cleanl<strong>in</strong>ess, purity; on the contrary, it is a<br />

codename for kill<strong>in</strong>g and/or expell<strong>in</strong>g people who are undesirable because of their national and/or religious<br />

identity, or because of the language they speak. The term really means “ethnic kill<strong>in</strong>g,” ethnocide, which is<br />

<strong>in</strong>deed different from genocide, but it is related to it <strong>in</strong> be<strong>in</strong>g totally unacceptable, someth<strong>in</strong>g to be prosecuted<br />

by the <strong>in</strong>ternational community.<br />

On one of my first trips to Western <strong>Europe</strong> I came across a book entitled Katyn: A Crime without Parallel.<br />

14 S<strong>in</strong>ce then I learned that, sadly, the brutal murder of tens of thousands of Polish POWs by the Soviet<br />

NKVD was not without parallel; it was surpassed only too often. Before the Balkan horrors of the 1990s I<br />

shared the belief of so many people that after the crimes of Hitler’s Nazism and Stal<strong>in</strong>’s Communism similar<br />

actions could not happen aga<strong>in</strong>. We were mistaken, and that is how the title of the present conference<br />

was born.<br />

In the course of our proceed<strong>in</strong>gs we heard scholarly accounts of little-known forced re-settlements, mass<br />

murders, and war crimes: the fate of the Greeks of Asia M<strong>in</strong>or, that of the Crimean Tatars and other smaller<br />

peoples <strong>in</strong> the Soviet Union, and the largely untold suffer<strong>in</strong>g and eventual elim<strong>in</strong>ation of the Germans who<br />

used to live <strong>in</strong> Bohemia, <strong>in</strong> Transylvania, <strong>in</strong> the Banat and the Vojvod<strong>in</strong>a. Another hardly known story, described<br />

<strong>in</strong> four papers, is the massive reduction <strong>in</strong> the size and proportion of the Hungarian populations <strong>in</strong><br />

Slovakia, Romania, and Yugoslavia.<br />

My message is not simply to highlight another sad story of abuse. My aim is more positive: it is an effort<br />

to show that the horrors of Bosnia and Kosovo were not <strong>in</strong>evitable, that the coexistence and peaceful cooperation<br />

of peoples who live side-by-side, often <strong>in</strong>term<strong>in</strong>gled, is possible, that there are promis<strong>in</strong>g models for<br />

this k<strong>in</strong>d of arrangement both <strong>in</strong> the past and <strong>in</strong> the present. In my view the most viable way to such cooperation<br />

is the Swiss model of arrang<strong>in</strong>g the various ethnic groups of a country <strong>in</strong>to separate Kantons.<br />

14 Louis Fitzgibbon, Katyn: A Crime Without Parallel (Dubl<strong>in</strong>, 1971, 1975).

16<br />

The Confederatio Helvetica as Model<br />

Louis Kossuth, the leader of the War for Hungarian Independence, writ<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> exile <strong>in</strong> 1862, proposed a Confederation<br />

of the Danubian Nations as the best guarantee aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>in</strong>terference and dom<strong>in</strong>ation by the nearby<br />

great powers and as a solution for handl<strong>in</strong>g the conflict<strong>in</strong>g territorial claims of the many smaller peoples liv<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong> the Danube Bas<strong>in</strong>. He ended his essay with a peroration: “Unity, agreement, fraternity among Hungarians,<br />

Slovaks and Romanians! Behold, my most ardent desire, my s<strong>in</strong>cerest advice! Behold, a blithesome<br />

future for us all!” 15 More than fifty years later, at the end of World War I, Oszkár [Oscar] Jászi, a long-time<br />

advocate of the rights of the non-Hungarian nationalities of Hungary, soon an exile <strong>in</strong> Austria, and later a<br />

Professor at Oberl<strong>in</strong> College, Ohio, wrote a book which advocated the replacement of the dual Austro-<br />

Hungarian Monarchy by a federation of German Austria, Czech Bohemia, Hungary, Polish-Ukra<strong>in</strong>ian Galicia<br />

and Croatia, mak<strong>in</strong>g up “The United States of the Danube.” He called for the adoption of the Swiss Kanton<br />

system, where the adm<strong>in</strong>istrative units of a region would reflect the ethnic composition of the population.<br />

16 In this way the historic K<strong>in</strong>gdom of Hungary was to become “a k<strong>in</strong>d of Eastern Switzerland,” where<br />

the various nationalities would enjoy territorial and/or cultural autonomy. Jászi was not a lonely dreamer:<br />

from the n<strong>in</strong>eteenth–century Czech František Palacky to the Romanian Aurel Popovici and the Austrian Otto<br />

Bauer and Karl Renner <strong>in</strong> the 1900s, many Central <strong>Europe</strong>an political th<strong>in</strong>kers believed that the best way to<br />

assure the peaceful coexistence of the eleven national groups liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the Habsburg Monarchy lay <strong>in</strong> national<br />

autonomies, a k<strong>in</strong>d of compromise between total separation (i.e., <strong>in</strong>dependence) and enforced unity. 17<br />

A plan similar to Jászi’s was submitted to the British Foreign Office <strong>in</strong> October, 1918, by Leo Amery, an<br />

adviser to the British Prime M<strong>in</strong>ister, Lloyd George. Its conclusion was: “Permanent stability and prosperity<br />

could best be secured by a new Danubian Confederation compris<strong>in</strong>g German Austria, Bohemia, Hungary,<br />

Yugoslavia, Rumania and probably also Bulgaria.… In any case the various nationalities of Central <strong>Europe</strong><br />

are so <strong>in</strong>terlocked, and their racial frontiers are so unsuitable as the frontiers of really <strong>in</strong>dependent sovereign<br />

states, that the only satisfactory and permanent work<strong>in</strong>g policy for them lies <strong>in</strong> their <strong>in</strong>corporation <strong>in</strong> a nonnational<br />

superstate.” 18 Almost simultaneously the American team prepar<strong>in</strong>g peace, the Inquiry, when draw<strong>in</strong>g<br />

up proposals for new states to emerge <strong>in</strong> Central <strong>Europe</strong>, proposed the transformation of Austria-<br />

Hungary <strong>in</strong>to a federation. 19 Even when the allies decided to work for the break-up of the Monarchy, the<br />

f<strong>in</strong>al U.S. recommendation came to the conclusion that “the frontiers supposed [sic] are unsatisfactory as the<br />

<strong>in</strong>ternational boundaries of sovereign states. It has been found impossible to discover such l<strong>in</strong>es, which<br />

would be at the same time just and practical.… many of these difficulties would disappear if the boundaries<br />

were to be drawn with the purpose of separat<strong>in</strong>g not <strong>in</strong>dependent nations, but component portions of a federalized<br />

state.” 20<br />

15 Ferencz Kossuth, ed., Kossuth Lajos Iratai [The Papers of L. Kossuth], vol. 6 (Budapest, 1898): 9–12.<br />

16 Oszkár Jászi, A Monarchia jövője: a dualizmus bukása és a Dunai Egyesült Államok [The Future of the Monarchy: the Fall of Dualism and the United<br />

States of the Danube] (Budapest, 1918; new edition, 1988). Cf. István Borsody, “Oszkár Jászi’s Vision of Peace,” <strong>in</strong> Hungary’s Historical Legacies: Studies<br />

<strong>in</strong> Honor of Steven Béla Várdy, ed. Dennis P. Hupchik and R. William Weisberger (Boulder, Col., 2000), 116-129.<br />

17 Ignác Romsics, "Plans and Projects for Integration <strong>in</strong> East Central <strong>Europe</strong> <strong>in</strong> the 19 th and 20 th Centuries: Toward a Typology," <strong>in</strong> Geopolitics <strong>in</strong> the<br />

Danube Region: Hungarian Reconciliation Efforts, 1848–1998, ed. Ignác Romsics and Béla K. Király (Budapest, 1999), 1–4. Cf. Éva R<strong>in</strong>g, ed., Helyünk<br />

Európában [Hungary’s Place <strong>in</strong> <strong>Europe</strong>] (Budapest, 1986), esp. vol. 1: 577–579.<br />

18 "The Austro-Hungarian Problem," 20 October, 1918, Public Record Office, London, FO 371/3136/17223. See Géza Jeszenszky, "Peace and Security <strong>in</strong><br />

Central <strong>Europe</strong>: Its British Programme dur<strong>in</strong>g World War I," Etudes historiques hongroises 1985 (Budapest, 1985), 457-482.<br />

19 Charles Seymour, "Austria-Hungary Federalized With<strong>in</strong> Exist<strong>in</strong>g Boundaries," May 25, 1918, Inquiry Document 509, RG 256, National Archives,<br />

Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, D.C. (hereafter, NA). See Géza Jeszenszky, “A dunai államszövetség eszméje Nagy-Britanniában és az Egyesült Államokban az I. világháború<br />

alatt” [The Idea of a Danubian Federation <strong>in</strong> Great Brita<strong>in</strong> and the United States dur<strong>in</strong>g World War I], Századok (1988), 659. Cf. Magda Ádám, ”Plan for a<br />

Rearrangement of Central <strong>Europe</strong>, 1918,” <strong>in</strong> Hungarians and Their Neighbors <strong>in</strong> Modern Times, 1867-1950, ed. Ferenc Glatz (Boulder, Col., 1995), 77-83.<br />

20 Inquiry Doc. 514, RG 256, NA. Géza Jeszenszky, "Peace and Security <strong>in</strong> Central <strong>Europe</strong>," 662. Cf. Tibor Glant, Through the Prism of the Habsburg<br />

Monarchy: Hungary <strong>in</strong> American Diplomacy and Public Op<strong>in</strong>ion Dur<strong>in</strong>g World War I (New York, 1998), 220-23.

The idea of us<strong>in</strong>g the Swiss model for manag<strong>in</strong>g the ethnic mosaic of a large part of Central and Eastern<br />

<strong>Europe</strong> was revived dur<strong>in</strong>g the Second World War. One of the many plans for a fair postwar settlement and a<br />

solution of the problem of Transylvania, traditionally a bone of contention between Hungary and Romania,<br />

was drawn up by a member of the Hungarian Parliament, Endre Bajcsy-Zsil<strong>in</strong>szky. 21 In his book published<br />

<strong>in</strong> 1944 <strong>in</strong> English on the future of Transylvania, 22 he argued for the cantonal model <strong>in</strong> an <strong>in</strong>dependent state,<br />

hav<strong>in</strong>g separate as well as mixed Hungarian and Romanian territorial units, thus preserv<strong>in</strong>g ethnic peace <strong>in</strong><br />

that historic prov<strong>in</strong>ce, where religious tolerance was enacted already <strong>in</strong> the sixteenth century. A recent study<br />

by a Hungarian writer recalls the past plans for Transylvania to be reconstituted along the Swiss model and<br />

argues for a system of autonomous regions. 23<br />

17<br />

The <strong>Ethnic</strong> Mosaic <strong>in</strong> Central <strong>Europe</strong><br />

About a thousand years ago Central <strong>Europe</strong> embraced Christianity and four k<strong>in</strong>gdoms emerged: Poland,<br />

Bohemia (the land of the Czechs), Hungary, and Croatia. Serbia and two Romanian pr<strong>in</strong>cipalities, Wallachia<br />

and Moldova, follow<strong>in</strong>g the rite of the Eastern Orthodox Church, were established two or three centuries<br />

later. While <strong>in</strong> all these states one national group (and language) was dom<strong>in</strong>ant, they conta<strong>in</strong>ed several ethnic<br />

m<strong>in</strong>orities, and there was a constant <strong>in</strong>flux of new settlers: ma<strong>in</strong>ly Germans and Turkic peoples (especially<br />

Cumanians), but also Romanians (then called Wallachs) and some Jews. In the first group Lat<strong>in</strong>, <strong>in</strong> the<br />

second Old Church Slavic was the language of learn<strong>in</strong>g and adm<strong>in</strong>istration. In everyday life each person<br />

was free to use whichever language he or she preferred, and many people spoke several languages. Loyalty<br />

to the state, however, was not based on language or ethnicity, but rather on allegiance to the sovereign K<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

who reigned Dei gratia, by the grace of God. The settlers, hospes, whether import<strong>in</strong>g skills and trades to the<br />

towns; m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g gold, silver, or salt; or work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the fields, were granted royal privileges, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the free<br />

use of their language and the runn<strong>in</strong>g of their own local affairs. When two or more ethnic groups lived <strong>in</strong> the<br />

same town they usually <strong>in</strong>habited separate quarters, and the mayor or judge as well as the councilors were<br />

selected on a rotational basis. <strong>Ethnic</strong> strife was rare, and the K<strong>in</strong>gs were ready to protect the m<strong>in</strong>orities,<br />

whose taxes were an important source of revenue. The various ethnic islands, primarily the German “Saxons”<br />

<strong>in</strong> Transylvania and the Zipser <strong>in</strong> North-Eastern Hungary, were able to preserve their l<strong>in</strong>guistic identity<br />

until the twentieth century.<br />

Wars and epidemics naturally took a heavy toll of the population, but systematic kill<strong>in</strong>g based on language<br />

or ethnic identity was rare. When the mult<strong>in</strong>ational Ottoman Empire, dom<strong>in</strong>ated by Islamic Turks, but<br />

often managed by Greeks and Albanians, conquered the Balkan Pen<strong>in</strong>sula, the conflict undoubtedly had a<br />

religious connotation. The ensu<strong>in</strong>g centuries of warfare had a most detrimental impact on the evolution of<br />

Southeastern <strong>Europe</strong>, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g decimat<strong>in</strong>g the population. The armies of the Sultan (often Tatar, Slavic or<br />

Albanian auxiliary troops) killed, plundered and took people <strong>in</strong>to slavery by the tens of thousands, but the<br />

mercenaries of the Habsburg k<strong>in</strong>gs were not much better <strong>in</strong> their treatment of the population of Hungary either.<br />

Contemporary travelers like Lady Mary Montague described the devastations <strong>in</strong> graphic terms. Follow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the expulsion of the Ottomans from Hungary <strong>in</strong> the early eighteenth century, big changes occurred <strong>in</strong> the<br />

ethnic composition of Central <strong>Europe</strong>. The devastated and depopulated southeastern part of the Great Hungarian<br />

Pla<strong>in</strong> saw massive organized colonization ma<strong>in</strong>ly by Germans (called Swabians) arriv<strong>in</strong>g from the<br />

21 Endre Bajcsy-Zsil<strong>in</strong>szky (1886-1944), Hungarian author and politician. He was a courageous opponent of Nazi Germany, a leader of the Hungarian<br />

resistance, who was executed by the Hungarian hirel<strong>in</strong>gs of Hitler on Christmas Eve, 1944.<br />

22 Endre Bajcsy-Zsil<strong>in</strong>szky, Transylvania: Past and Future (Geneve, 1944).<br />

23 Béla Pomogáts, “A Chance Missed: Transylvania as ‘Switzerland of the East,’” M<strong>in</strong>orities Research No. 2. (2000): 132-145.

18<br />

West, Slovaks from the North, and Rusyns from the Northeastern Carpathians, mov<strong>in</strong>g to the fertile and<br />

“free” land of today’s Vojvod<strong>in</strong>a and the Banat. Serbs and Romanians arrived, also <strong>in</strong> great numbers, escap<strong>in</strong>g<br />

poverty, mismanagement, and—occasionally—religious <strong>in</strong>tolerance under Ottoman rule. The Habsburg<br />

Emperor-K<strong>in</strong>gs established a military borderland to protect their possessions, the local Catholic Croats be<strong>in</strong>g<br />

jo<strong>in</strong>ed by Orthodox Serbs—thus <strong>in</strong>advertently lay<strong>in</strong>g the foundation for the brutal conflicts of the twentieth<br />

century. Both the older and the new ethnic islands had substantial territorial as well as religious autonomy.<br />

Croatia had its own Diet, the Sabor <strong>in</strong> Zagreb; the military border from the Austrian Alps to the eastern<br />

Carpathians had its own military adm<strong>in</strong>istration; and the Orthodox Serb Patriarch of Karlowitz as well as<br />

the Romanians of Transylvania enjoyed religious freedom and autonomy.<br />

The Orig<strong>in</strong>s of <strong>Ethnic</strong> Conflicts<br />

It was largely due to the Ottoman wars and subsequent colonization that by the late eighteenth century the<br />

Hungarians became a m<strong>in</strong>ority <strong>in</strong> the K<strong>in</strong>gdom of Hungary, but that became an issue only from the 1830s<br />

on, with the rise of nationalism, when language and its concomitant, ethnic identity, became the primary basis<br />

for group loyalty. “National awaken<strong>in</strong>g” was bound to lead to trouble wherever populations were ethnically<br />

mixed: <strong>in</strong> Hungary, <strong>in</strong> Poland-Lithuania, and all over the Balkans. The towns were often <strong>in</strong>habited by<br />

one national group, while the villages nearby by another. The situation was complicated by the cleavage between<br />

landown<strong>in</strong>g nobles, <strong>in</strong>dustrious burghers of towns, and the poor serfs, who started to move to the urban<br />

and <strong>in</strong>dustrializ<strong>in</strong>g areas. The most typical case was <strong>in</strong> eastern Galicia, with a Polish-speak<strong>in</strong>g gentry<br />

and a Ukra<strong>in</strong>ian rural population, where the towns had also sizeable German and Yiddish-speak<strong>in</strong>g Jewish<br />

population. A similar, but even more complicated, pattern could be observed <strong>in</strong> Transylvania, where the nobility<br />

was Hungarian (absorb<strong>in</strong>g also some Romanians), the urban element divided between Hungarians and<br />

Germans, while the peasants were both Hungarian (called Székely or Szekler <strong>in</strong> the southeastern corner of<br />

the pr<strong>in</strong>cipality), German (or more properly Sächsisch <strong>in</strong> the Königsboden), and Romanian, the latter mov<strong>in</strong>g<br />

down from mounta<strong>in</strong> pastures to the destroyed Hungarian villages, or arriv<strong>in</strong>g from Moldavia and Wallachia<br />

over the Carpathians. Social tensions also grew with <strong>in</strong>dustrialization sett<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>.<br />

Contrary to the commonly held belief that “ethnic cleans<strong>in</strong>g,” or <strong>in</strong> a more general way, present-day ethnic<br />

conflicts go back to centuries of animosities and hostilities, there were far fewer wars between the peoples<br />

of the Danubian Bas<strong>in</strong> than <strong>in</strong> Western or Northern <strong>Europe</strong>. The first serious nationalist clashes between<br />

them occurred only <strong>in</strong> 1848, dur<strong>in</strong>g “the spr<strong>in</strong>gtime of nations,” when the common desire for liberty,<br />

equality, and national freedom floundered on the territorial issue, on the conflict<strong>in</strong>g claims to the same territory,<br />

e.g. Transylvania. It was particularly difficult to separate peoples along national l<strong>in</strong>es when they lived<br />

mixed, overlapp<strong>in</strong>g each other. The call was for “Home Rule,” national <strong>in</strong>dependence, or at least for very<br />

substantial territorial autonomy. The new government of Hungary, <strong>in</strong> accordance with the pr<strong>in</strong>ciples of contemporary<br />

liberalism, believed that equality before the law and the new constitutional system would satisfy<br />

the non-Hungarian citizens of the country, and rejected demands for federaliz<strong>in</strong>g the country along national<br />

l<strong>in</strong>es. The reactionary advisers of the Habsburg K<strong>in</strong>g sent <strong>in</strong> an army to suppress Hungary, and by skillfully<br />

manipulat<strong>in</strong>g the Croatian, Serbian, and Romanian peasantry, led by loyal, “Habsburgtreu” priests and officers,<br />

they <strong>in</strong>duced these “nationalities” to rebel aga<strong>in</strong>st the government. The Hungarians were supported by<br />

the vast majority of the Slovak, German, and Rusyn nationalities and by all the Jews of the k<strong>in</strong>gdom, as well<br />