The Ardingly College Journal of History & International Relations

The Ardingly College Journal of History & International Relations

The Ardingly College Journal of History & International Relations

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

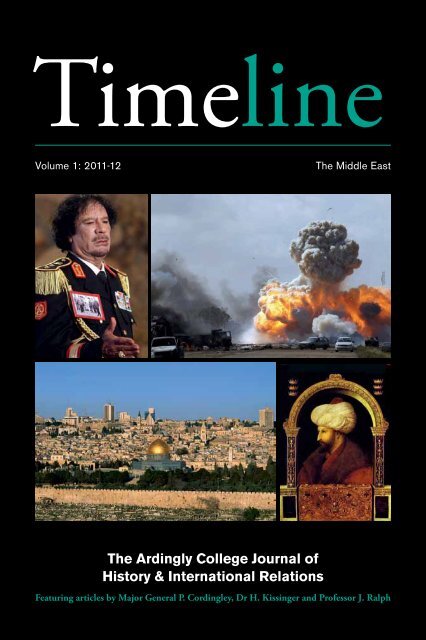

Timeline<br />

Volume 1: 2011-12<br />

<strong>The</strong> Middle East<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ardingly</strong> <strong>College</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>History</strong> & <strong>International</strong> <strong>Relations</strong><br />

Featuring articles by Major General P. Cordingley, Dr H. Kissinger and Pr<strong>of</strong>essor J. Ralph

Timeline<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ardingly</strong> <strong>College</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>History</strong> & <strong>International</strong> <strong>Relations</strong><br />

Volume 1: <strong>The</strong> Middle East<br />

11th Century Cottoniana or Anglo-Saxon Map <strong>of</strong> the Middle East<br />

Staff Editor: Mr M. Jennings<br />

Student Editor: Charles Ward (U6th)<br />

Copy Editor: Bethany Reyniers (L6th)<br />

<strong>Ardingly</strong> Student Contributors: Jenny Elwin, Axel Fithen, Gustav Fithen, Thomas Gibbens,<br />

John Gibson, Amy Haines, Anastasia Harrington, Thomas O’Dell, Abidine Sakande, Kaan Tuncell,<br />

Charles Ward and Johannes Wullenweber<br />

Other Contributors are:<br />

Mr R. Alston, former Chair <strong>of</strong> Governors, <strong>Ardingly</strong> <strong>College</strong> & former UK Ambassador to the Oman<br />

Major General P. Cordingley, former commander <strong>of</strong> 7th Armoured Brigade during 1st Gulf War<br />

Tobias Chesser (Student <strong>of</strong> Hawthorns Prep School)<br />

Mr M. Jennings, Head <strong>of</strong> <strong>History</strong>, <strong>Ardingly</strong> <strong>College</strong><br />

Mr A. Kendry, <strong>The</strong>ologian<br />

Mr D. Maclean, Head <strong>of</strong> Divinity, <strong>Ardingly</strong> <strong>College</strong><br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor J. Ralph, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> <strong>International</strong> <strong>Relations</strong> at Leeds University<br />

And Dr H. Kissinger, former US Secretary <strong>of</strong> State<br />

Images from the front cover are <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem, a NATO airstrike on Gadaffi’s forces near Benghazi,<br />

Sultan Mehmet II and Colonel Gadaffi.

Contents<br />

Editorials<br />

Staff – Mr M. Jennings, Head <strong>of</strong> Department<br />

Student – Charles Ward (U6th)<br />

history articles<br />

Tel Megiddo and the Politics <strong>of</strong> the Middle East, by Mr D. McLean Page 1<br />

Holy, Holy, Holy: A theological history <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem in 3 Faiths by Mr A. Kendry Page 3<br />

<strong>The</strong> 1st Crusade and the Capture <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem, 1099 by Axel Fithen Page 7<br />

Was the ability <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem’s rulers the main reason for the survival <strong>of</strong> the Page 10<br />

estates during the twelfth century By Anastasia Harrington<br />

1187, <strong>The</strong> Battle <strong>of</strong> Hattin and <strong>The</strong> Capture <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem by John Gibson Page 14<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>of</strong> Saladin by Charles Ward Page 17<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>of</strong> Richard ‘the Lionheart’ by Tobias Chesser Page 19<br />

<strong>The</strong> Great Siege <strong>of</strong> Constantinople in 1453 by Mr M. Jennings Page 21<br />

Photomontage <strong>of</strong> civil strife in Syria by Thomas Gibbens Page 46<br />

What does Turkey’s relationship with Syria mean to the region, Page 47<br />

the West and to itself By Kaan Tuncel<br />

Where to now Israel Israel’s foreign policy challenges by Mr M. Jennings Page 49<br />

Photomontage <strong>of</strong> recent events in Iran by Thomas Gibbens Page 52<br />

American Foreign Policy towards the Middle East 2011 Page 53<br />

by Pr<strong>of</strong>essor J. Ralph, Leeds University<br />

Defining a U.S. role in the Arab Spring by Dr H. Kissinger Page 56<br />

<strong>The</strong> Last Word Page 58<br />

<strong>The</strong> First Three Afghan Wars by Mr R. Alston CMG, QSO, DL Page 26<br />

<strong>The</strong> Arab Revolt 1916-18 by Gustav Fithen Page 29<br />

Reflections on the First Gulf War by Major General P. Cordingley DSO, DSc, FRGS Page 31<br />

<strong>International</strong> <strong>Relations</strong> articles<br />

Map & commentary <strong>of</strong> Dictatorial Leaders in the Middle East <strong>of</strong> 2011 Page 35<br />

by Abidine Sakande & Johannes Wullenweber<br />

Photomontage <strong>of</strong> the Tunisian Revolution by Thomas Gibbens Page 37<br />

Tunisia, the first <strong>of</strong> the Arab Spring revolutions by Thomas O’Dell Page 38<br />

Photomontage <strong>of</strong> the Egyptian Revolution by Thomas Gibbens Page 40<br />

1001 Egyptian Knights: A Drama in Three Acts – Page 41<br />

Egypt and the on-going revolution by Amy Haines<br />

<strong>The</strong> Libyan Revolution by Jenny Elwin Page 43

Staff Editorial...<br />

Welcome to<br />

the first issue <strong>of</strong><br />

Timeline, the<br />

<strong>Ardingly</strong> <strong>College</strong><br />

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>History</strong><br />

and <strong>International</strong><br />

<strong>Relations</strong>. Timeline<br />

combines these<br />

two important<br />

and popular<br />

subjects into one<br />

publication so that<br />

current and historical themes can be explored and their<br />

significance over time more fully understood. That explains<br />

why the <strong>Journal</strong> is called Timeline. So why choose the<br />

Middle East as Timeline’s first theme Well, since work on<br />

this began back in the summer <strong>of</strong> 2011 and this journal’s<br />

purpose is to examine the relationship between the past<br />

and the present, I could think <strong>of</strong> no more appropriate and<br />

relevant case study to our time than the Middle East.<br />

Over the last 18 months, the attention <strong>of</strong> the world has<br />

been captivated by civil wars in Libya and Syria and by<br />

revolutions and other popular protests in Tunisia, Egypt<br />

and elsewhere. Consequently, a number <strong>of</strong> the articles by<br />

<strong>Ardingly</strong> students in the second half <strong>of</strong> the journal reflect<br />

this. However, last year the West took more than just an<br />

interest in the Middle East. In the case <strong>of</strong> Libya, NATO’s<br />

military intervention raised the paradigm <strong>of</strong> the <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

stormy relationship between the West and the Middle<br />

East. Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Ralph’s article explores how the West’s<br />

method <strong>of</strong> legitimising its use <strong>of</strong> force may cause it further<br />

problems with other countries on the UN security council<br />

as well as the Middle East in the future should the need<br />

for intervention arise again. With the conflict in Syria<br />

unresolved that situation is more than just a possibility.<br />

With the grim spectre <strong>of</strong> the West’s lengthy and costly<br />

involvement in Afghanistan, Dr Henry Kissinger’s article<br />

explores how one western country, the U.S. is reaching for<br />

a new role during this prolonged Arab Spring. He explains<br />

what challenges and choices the U.S. government is facing.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se themes and tough choices are echoed throughout<br />

the West. Israel too has had to seriously rethink its foreign<br />

relations not just with its former allies but also Iran and<br />

Palestine. Much <strong>of</strong> the future <strong>of</strong> the region (and potentially<br />

the world) hangs upon how successfully Israel is in<br />

maintaining peace with these two volatile neighbours.<br />

Furthermore, the problem <strong>of</strong> determining foreign policy<br />

towards the Middle East is not new. Over the last few<br />

millennia, the West’s relationship with the Middle East<br />

has been plagued with ambitious power struggles that<br />

have erupted into war. Timeline’s first few articles explore<br />

these in relation to the strategically significant locations <strong>of</strong><br />

Megiddo, Jerusalem and Constantinople. <strong>The</strong>y have formed<br />

the backdrop for much <strong>of</strong> the history <strong>of</strong> the region and it is<br />

not hard to see why. Articles from Mr Mclean, Mr Kendry<br />

and myself, illustrate that at different times, these places<br />

have been centres and cross roads <strong>of</strong> civilisation, culture,<br />

economic strength and religious zeal. Altogether, ownership<br />

<strong>of</strong> them has brought prestige and power; thus explaining<br />

why they have been so regularly contested. Indeed, so has<br />

much <strong>of</strong> the Middle East at one time or another. Timeline<br />

charts a number <strong>of</strong> these conflicts from the Crusades right<br />

the way through to the First Gulf War <strong>of</strong> 1991. In particular,<br />

articles by Mr Alston and Major General Cordingley<br />

explore many <strong>of</strong> the interesting and indeed controversial<br />

aspects <strong>of</strong> these conflicts including the reasons for Britain’s<br />

involvement in them. Both authors have considerable<br />

experience <strong>of</strong> working in the Middle East in their respective<br />

diplomatic and military roles and we are very fortunate to be<br />

able to view these conflicts through their experienced eyes.<br />

But what <strong>of</strong> the architects <strong>of</strong> these wars, the warrior kings,<br />

sultans and generals Articles by Tobias Chesser,<br />

Charles Ward and Gustav Fithen, explore the significance <strong>of</strong><br />

the role <strong>of</strong> the individual in shaping the outcomes <strong>of</strong> major<br />

historical change. This issue examines two <strong>of</strong> the Middle<br />

Ages’ most iconic leaders, Richard the Lionheart and<br />

Saladin, and how their destinies and the fate <strong>of</strong> the Middle<br />

East became inextricably linked. Similarly, a further article<br />

explores the Arab Revolt and the important part played by<br />

T. E. Lawrence. After all, the study <strong>of</strong> <strong>History</strong> should also be<br />

about significant people as well as events and themes.<br />

On that subject, I want to thank my fellow editor and<br />

6th form medieval history student, Charles Ward whose<br />

calm manner and conscientious dedication to this project<br />

made it happen. His persistence in pursuing articles from<br />

fellow students was invaluable. I also want to thank all the<br />

other contributors from their many different backgrounds.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y are an eclectic lot and so are their submissions.<br />

Consequently, this journal is all the richer for them. To<br />

them, I am very grateful for their labours. Do please write<br />

in to respond to the views expressed in their articles or even<br />

to contribute an article yourself to our next issue. For more<br />

on how to do that please visit the inside back page.<br />

Mr M. Jennings, Summer 2012<br />

Editor<br />

Student Editorial...<br />

As a student <strong>of</strong> <strong>Ardingly</strong> <strong>College</strong>, I feel especially proud and privileged to be<br />

able to say I have had the opportunity to contribute something <strong>of</strong> significant<br />

value to the <strong>College</strong>. Timeline is a brand new publication with a unique<br />

angle organised by the Head <strong>of</strong> <strong>History</strong>, Mr Jennings, and myself. <strong>The</strong><br />

magazine successfully integrates the rich and fascinating world <strong>of</strong> <strong>History</strong><br />

with current international affairs which so populate the news today. Our aim<br />

is to involve the students <strong>of</strong> <strong>Ardingly</strong> <strong>College</strong> in Timeline by encouraging<br />

them to contribute pieces about areas <strong>of</strong> history or current happenings which<br />

particularly interest them. We wish to nurture an interest in the broader<br />

subject <strong>of</strong> <strong>History</strong> which we hope will not only be passed on to the readers but<br />

also encourage them to think and explore further about the issues arising from<br />

their articles. I am pleased to report that within the up and coming pages, a<br />

plethora <strong>of</strong> eclectic contributions (modern and medieval alike) from around<br />

the world have been submitted. <strong>The</strong>se range from the likes <strong>of</strong> the Siege <strong>of</strong><br />

Jerusalem, to dynamic maps plotting the rise <strong>of</strong> the Arab Spring. Ladies and<br />

gentleman, I present to you, <strong>Ardingly</strong> <strong>College</strong>’s <strong>History</strong> and <strong>International</strong><br />

<strong>Relations</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>, Timeline!<br />

Charles Ward (U6th)

“And they assembled them<br />

at the place that in Hebrew<br />

is called Harmaggedon.”<br />

Tel Megiddo and the Politics <strong>of</strong> the Middle East<br />

<strong>The</strong> word ‘Armageddon’ conjures images <strong>of</strong><br />

destruction, judgement and terror. Indeed,<br />

the quotation in the title is from the Book <strong>of</strong><br />

Revelation, describing the last battle before God’s<br />

judgement. Yet the name appears to be the<br />

anglicisation <strong>of</strong> a quiet little hill in Israel – Har (or<br />

Tel) Megiddo. How has this quiet backwater <strong>of</strong><br />

the Jezreel Valley come to be associated with the<br />

eschaton and with divine judgement <strong>The</strong> answer<br />

lies in its strategic position. This has made it a<br />

very important staging post for approximately nine<br />

thousand years and may continue to symbolise<br />

the importance <strong>of</strong> the area to this day.<br />

Megiddo was first occupied in approximately<br />

7000 BC for reasons that ensured its survival for<br />

several thousand years. <strong>The</strong> great civilisations<br />

<strong>of</strong> Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) needed a<br />

route to the Mediterranean in order to engage<br />

in trade. However, as the crow flies, they are<br />

divided from the sea by desert, making a short<br />

journey impossible. <strong>The</strong>refore, in order to reach<br />

the ports they were compelled to travel northwest<br />

before turning south into the relatively<br />

lush lands <strong>of</strong> Israel and Judah; Megiddo stood<br />

at the head <strong>of</strong> this trade route, the strategically<br />

important ‘Derekh ha-Yam’, or ‘<strong>The</strong> Way <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Sea’. It is not surprising, therefore, that it has<br />

been the site <strong>of</strong> at least three decisive battles in<br />

history; it continues to play a symbolic role in the<br />

relationship between the east and west.<br />

Mr D. McLean<br />

<strong>The</strong> first battle took place in April 1457 BC<br />

between Pharaoh Thutmose III <strong>of</strong> Egypt and<br />

the combined rebel forces <strong>of</strong> the Mitanni people<br />

<strong>of</strong> Kadesh, and the Canaanites <strong>of</strong> Megiddo. A<br />

decisive Egyptian victory on the battlefield led<br />

to a seven month siege <strong>of</strong> the city. Consequently<br />

the engagement led directly to the expansion<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Egyptian empire to its greatest ever<br />

extent, spreading north until it bordered on the<br />

lands <strong>of</strong> the Hittite empire (modern Turkey and<br />

Syria). Thankfully Thutmose did not destroy the<br />

city and it lived on, but it appears that the site<br />

has not been occupied since the Babylonian<br />

invasion <strong>of</strong> 586 BC. Even so, its importance<br />

continued. <strong>The</strong> second battle, approximately<br />

850 years after the first, in 609 BC, was equally<br />

significant and indeed is recorded twice in the<br />

Bible; King Josiah <strong>of</strong> Judah refused Pharaoh<br />

Necho II <strong>of</strong> Egypt permission to travel through<br />

his country to fight the Babylonians further<br />

north in Syria. In response Necho attacked the<br />

assembled Judahite forces, his archers killing<br />

Josiah in the process. This was the beginning<br />

<strong>of</strong> the downfall <strong>of</strong> the independent state <strong>of</strong><br />

Judah. It spelled the end <strong>of</strong> an independent<br />

Jewish state as on his return from Syria Necho<br />

also deposed Josiah’s son and imposed his<br />

own candidate as King. Megiddo thus again<br />

played an important part in the socio-political<br />

development <strong>of</strong> the ancient world.<br />

<strong>The</strong> third battle is surprisingly modern;<br />

Megiddo was the place at which the British<br />

Army, under General Edmund Allenby, defeated<br />

the Turkish Ottoman troops under the command<br />

<strong>of</strong> the German General Liman Von Sanders in<br />

September 1918. It was this battle that broke<br />

the stalemate that had emerged after the British<br />

capture <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem late in 1917. Yet again,<br />

though it had been uninhabited for over 2500<br />

years, Megiddo played a pivotal role in the<br />

development <strong>of</strong> the Middle East. It contributed<br />

immensely to the downfall <strong>of</strong> the Ottoman<br />

Empire and affected the lives <strong>of</strong> millions <strong>of</strong> people.<br />

This significance continues to be recognised<br />

to the present day and Megiddo was the site<br />

<strong>of</strong> Pope Paul VI’s talks in 1964 with the Israeli<br />

President and Prime Minister. Though the<br />

Derekh ha-Yam fell into disuse as a trade route<br />

long ago, the strategic importance <strong>of</strong> a little hill<br />

a few miles south-west <strong>of</strong> Nazareth means that<br />

it is not hard to see why John the Evangelist,<br />

when writing the Book <strong>of</strong> Revelation, chose<br />

Megiddo as the site <strong>of</strong> his last battle in which<br />

the returned Christ would defeat the Devil.<br />

We might not all be expecting an impending<br />

apocalypse but we can certainly agree that a<br />

place so vitally important over many thousands<br />

<strong>of</strong> years <strong>of</strong> history could very possibly be so<br />

again in the future. Indeed, it might well be<br />

thought <strong>of</strong> as an unfortunate symbol <strong>of</strong> the<br />

unsettling and unresolved religious and political<br />

tensions <strong>of</strong> the Levant.<br />

Dan McLean is Head <strong>of</strong> Divinity and<br />

Philosophy at <strong>Ardingly</strong> <strong>College</strong>. Before<br />

arriving at Michaelmas 2011 he read<br />

<strong>The</strong>ology at Oriel <strong>College</strong>, Oxford and prior<br />

to that he served for five years as an <strong>of</strong>ficer<br />

in the Royal Navy.<br />

Megiddo<br />

Viscount Allenby <strong>of</strong> Megiddo<br />

Left: Egyptian War Chariot<br />

1 2

Holy, Holy, Holy:<br />

A <strong>The</strong>ological <strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem in Three Faiths<br />

Jerusalem seems to have existed<br />

from the very earliest times <strong>of</strong><br />

human settlement in the Near East.<br />

<strong>The</strong> first references to it come from<br />

the second millennium BC when<br />

it might best be termed a small,<br />

independent city-state within a<br />

loose confederation <strong>of</strong> Caananite<br />

settlements. It was to grow in<br />

significance, both politically and<br />

religiously, until it can lay claim<br />

today to being the undisputed<br />

religious capital <strong>of</strong> the world: sacred<br />

to, and fought over by, the great<br />

religions <strong>of</strong> Judaism, Christianity,<br />

and Islam. This status brings with<br />

it a blessing and a curse for an<br />

historian. On the one hand we have<br />

a wealth <strong>of</strong> written and physical<br />

material – probably unparalleled for<br />

any other city – with which to help<br />

us reconstruct its past. On the other<br />

hand, perhaps equally unparalleled<br />

is the level <strong>of</strong> agenda that these<br />

sources demonstrate.<br />

Mr. A.D. Kendry<br />

“Glorious things <strong>of</strong> thee are spoken,<br />

Zion, city <strong>of</strong> our God;<br />

He whose word cannot be broken<br />

formed thee for His own abode;<br />

on the Rock <strong>of</strong> Ages founded,<br />

what can shake thy sure repose<br />

With salvation’s walls surrounded,<br />

thou may’st smile at all thy foes.”<br />

John Newton (1779)<br />

No one is neutral about Jerusalem.<br />

<strong>The</strong> city rose to prominence in<br />

the tenth century BC. A relatively<br />

insignificant town prior to this,<br />

it was chosen by the first king<br />

<strong>of</strong> Israel, David, as his capital.<br />

<strong>The</strong> choice was an odd one.<br />

Jerusalem, although in possession<br />

<strong>of</strong> several natural springs, is not<br />

obviously well-provided for in<br />

terms <strong>of</strong> natural resources and<br />

is only moderately-defensible in<br />

terms <strong>of</strong> topography. Its chief<br />

recommendation seems to be<br />

that it was fairly central in terms<br />

<strong>of</strong> the territory controlled by the<br />

House <strong>of</strong> David. To support the<br />

innovation <strong>of</strong> monarchy and its<br />

new capital, David also relocated<br />

the Ark <strong>of</strong> the Covenant – the<br />

preeminent cult-object <strong>of</strong> Yahweh,<br />

the Israelite high god – to the<br />

city. This meant that Jerusalem<br />

was also to become the primary<br />

cultic centre in ancient Israel and<br />

created a powerful political link<br />

between the kingship and religious<br />

worship. <strong>The</strong> following centuries<br />

saw the gradual suppression <strong>of</strong><br />

other religious sites and <strong>of</strong> the cults<br />

<strong>of</strong> rival gods, centralizing all power<br />

– sacred and pr<strong>of</strong>ane – within the<br />

‘Holy City’, whose fortunes were<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten directly equated with those <strong>of</strong><br />

the Jewish people. Jerusalem, put<br />

simply, is where God dwelt among<br />

His people.<br />

Arguably the greatest calamity in<br />

Jerusalem’s history was the city’s<br />

destruction in AD 70. <strong>The</strong> four<br />

year revolt <strong>of</strong> the Roman province<br />

<strong>of</strong> Judaea culminated in a savage<br />

assault on the city that is described<br />

in unremittingly-horrific detail by<br />

Flavius Josephus in his Jewish War.<br />

Internal conflict and severe food<br />

shortages, with the consequent<br />

starvation and disease, led to the<br />

city falling to the forces <strong>of</strong> Titus<br />

after an eight month siege. <strong>The</strong> final<br />

battle took place in the precincts<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Temple itself where the<br />

defenders expected the imminent<br />

intervention <strong>of</strong> the Messiah on<br />

their behalf and to save the<br />

Temple. His non-appearance<br />

led to the Temple and city being<br />

almost completely destroyed; its<br />

population crucified or enslaved.<br />

By this time, Jerusalem was the<br />

third largest city <strong>of</strong> the Roman<br />

Empire and the Temple – recently<br />

totally rebuilt by Herod the Great<br />

– was considered a wonder <strong>of</strong> the<br />

world. Judaea was an economically<br />

and politically significant province<br />

– the primary source <strong>of</strong> date and<br />

olive oil production in the Empire,<br />

with a military-strategic location<br />

bordering Rome’s only real rival for<br />

world domination. Its destruction<br />

sent ripples throughout the Empire:<br />

the city ruins were garrisoned and<br />

a large standing army remained<br />

for several decades as a desecrating<br />

presence on the Temple Mount.<br />

Following a second bloody revolt<br />

under Simeon bar Kochba in AD<br />

132-135, who re-took Jerusalem as<br />

his messianic capital, the Roman’s<br />

razed the city and rebuilt it as a<br />

Roman town, Aelia Capitolina.<br />

Relief from the Arch <strong>of</strong> Titus<br />

<strong>The</strong> Jews were banished from<br />

setting foot within its precincts<br />

on pain <strong>of</strong> death. <strong>The</strong> Temple<br />

Mount became a Temple to Jupiter<br />

Capitolinus.<br />

After the Peace <strong>of</strong> the Church in<br />

AD 313 and Constantine’s <strong>of</strong>ficial<br />

favouring <strong>of</strong> Christianity, the<br />

fledgling Christian community<br />

increased in size but Jerusalem still<br />

remained a small Roman town, far<br />

from the trade routes with political<br />

– and Christian – influence in<br />

Judaea still concentrated on<br />

the Mediterranean ports to the<br />

west. It was the pilgrimage <strong>of</strong><br />

the Emperor’s mother, Helena,<br />

to the city in AD 325 and her<br />

apparent rediscovery <strong>of</strong> the True<br />

Cross that inspired a renewed<br />

devotion to the city, this time<br />

amongst the Christian population<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Empire. Jerusalem was<br />

rebuilt with grand churches over<br />

the sites <strong>of</strong> the Lord’s life and<br />

Passion and the city thrived. <strong>The</strong><br />

old Temple Mount remained<br />

abandoned as a deliberate sign<br />

<strong>of</strong> the supersession <strong>of</strong> the Jewish<br />

religion. However, Jerusalem still<br />

remained a fraction <strong>of</strong> its former<br />

self in terms <strong>of</strong> population and<br />

size. It had no political power and<br />

evolution in international politics<br />

downplayed the significance <strong>of</strong> the<br />

frontier province. What the city<br />

had regained was its theological<br />

significance: even for the exiled<br />

Jews, the longing for a return to<br />

Jerusalem became codified in their<br />

liturgy which looked for an end<br />

to their exile from their spiritual<br />

home and the restoration <strong>of</strong><br />

Temple worship.<br />

In the mid-seventh century, the<br />

rapid military successes <strong>of</strong> early<br />

Islam led to the capturing <strong>of</strong> the<br />

city in AD 638, only six years<br />

after the death <strong>of</strong> Muhammad.<br />

<strong>The</strong> city had, by now, regained<br />

some <strong>of</strong> its commercial and<br />

strategic significance. Nevertheless<br />

the capture <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem had,<br />

more importantly, a religious<br />

significance for the early Muslims<br />

for two reasons. Firstly, the Prophet<br />

explicitly saw his revelation as a<br />

continuation and fulfilment <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Jewish and Christian narrative and<br />

thus recognised Jerusalem as a city<br />

especially sacred to God. <strong>The</strong> ‘Rock’<br />

on which the Holy <strong>of</strong> Holies <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Jerusalem Temple had stood was in<br />

Islam – as in Judaism – recognised<br />

as the foundation stone and centre<br />

<strong>of</strong> the world and the burial place <strong>of</strong><br />

View <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem<br />

3 4

Adam. Indeed, in the early years <strong>of</strong><br />

Muhammad’s movement the qibla<br />

– the direction <strong>of</strong> prayer – was<br />

not the Kaaba in Mecca but rather<br />

the abandoned Temple Mount in<br />

Jerusalem to the north. Despite<br />

the change within Muhammad’s<br />

lifetime, one <strong>of</strong> the earliest acts <strong>of</strong><br />

the Muslim occupiers was to erect<br />

the Dome <strong>of</strong> the Rock on this<br />

site. This was a conspicuous and<br />

ever-visible reminder to Christians<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Islamic ownership <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Holy City – the Dome being in<br />

direct line <strong>of</strong> site for Christians<br />

upon leaving the Church <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Holy Sepulchre after<br />

Mass. <strong>The</strong> second<br />

reason was the early<br />

identification <strong>of</strong> the<br />

site <strong>of</strong> the destination<br />

<strong>of</strong> the mysterious<br />

‘Night Journey’ <strong>of</strong><br />

the ‘Night <strong>of</strong> Power’<br />

<strong>of</strong> Muhammad with<br />

the Temple Mount.<br />

According to this tradition alluded<br />

to in the Qur’an, the Prophet<br />

had journeyed spiritually on a<br />

horse-like cryptid to ‘the farther<br />

sanctuary’, whence he had leaped<br />

up to heaven to commune with<br />

the company <strong>of</strong> former prophets.<br />

<strong>The</strong> site <strong>of</strong> the former Temple thus<br />

became the third-holiest site <strong>of</strong><br />

Islam in its own right – an accolade<br />

it retains today.<br />

Unbroken Muslim occupation <strong>of</strong><br />

the Holy City lasted nearly five<br />

centuries until the First Crusade<br />

when Pope Urban II’s call for<br />

a recapturing <strong>of</strong> the Holy Sites<br />

associated with the life <strong>of</strong> Christ<br />

met with a genuinely popular<br />

response across Europe.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Crusaders, many inspired<br />

with deep religious fervour and<br />

devotion, succeeded in expelling<br />

the Muslim occupiers in AD 1099<br />

and proclaimed the Kingdom <strong>of</strong><br />

Jerusalem. A victory Mass was<br />

duly celebrated at the Church <strong>of</strong><br />

the Holy Sepulchre and the Relic<br />

<strong>of</strong> the True Cross –which the<br />

Crusaders had taken their symbol<br />

– venerated and triumphantly<br />

processed around the city. <strong>The</strong><br />

Dome <strong>of</strong> the Rock and the other<br />

mosques within the city limits<br />

were converted into churches. This<br />

Crusader state lasted a century<br />

“<strong>The</strong> Palestinian people … desire an<br />

independent Muslim state with East Jerusalem<br />

as its capital. <strong>The</strong> Jewish state <strong>of</strong> Israel is<br />

unwilling, both on religious and strategic<br />

grounds, to countenance any division<br />

<strong>of</strong> the city.”<br />

before a Muslim reconquest<br />

lost the lands <strong>of</strong> the Christians<br />

– apparently conclusively. After<br />

the sacking <strong>of</strong> the city by Saladin<br />

in 1187, most <strong>of</strong> the Christians<br />

were expelled and Jews and<br />

Muslims encouraged to return.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Dome <strong>of</strong> the Rock became a<br />

mosque once more, though the<br />

Holy Sepulchre, whilst partially<br />

demolished, remained a church.<br />

Over the following five centuries<br />

the city’s fortunes, size, and<br />

political significance waxed and<br />

waned. By the beginning <strong>of</strong> the<br />

twentieth century Jerusalem was<br />

a small town forming part <strong>of</strong> the<br />

British mandate <strong>of</strong> Palestine. <strong>The</strong><br />

population was predominantly<br />

Muslim, with small Jewish<br />

and Christian minorities. Jews<br />

remained barred from stepping<br />

foot on the Temple Mount, where<br />

the Western Wall was all that<br />

remained <strong>of</strong> the Second Temple<br />

<strong>of</strong> Jesus’ time. <strong>The</strong> Christian holy<br />

sites were mostly administered by<br />

a small community <strong>of</strong> Franciscan<br />

friars, although fights – <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

physical – broke out sporadically<br />

between the different Christian<br />

communities remaining in the city.<br />

<strong>The</strong> modern period <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem<br />

is especially complex. After the<br />

expiring <strong>of</strong> the British mandate<br />

in 1948, it was intended that<br />

the city become an<br />

autonomous political<br />

entity. However,<br />

the plan was not<br />

implemented before<br />

the British withdrawal<br />

and the war that<br />

ensued after the<br />

Declaration <strong>of</strong> the<br />

State <strong>of</strong> Israel led to<br />

the city being partitioned, with the<br />

eastern half becoming Jordanian<br />

territory. During this period access<br />

to Jewish and Christian sites was<br />

severely curtailed to members <strong>of</strong><br />

those communities and many sites<br />

allegedly desecrated. Jordan joined<br />

the Arab alliance against Israel<br />

in the 1967 Six Day War, which<br />

ended in an impressive Israeli<br />

victory. East Jerusalem was captured<br />

and the united city declared the<br />

capital <strong>of</strong> greater Israel. To date,<br />

only the USA has moved its<br />

embassy from Tel Aviv to the city<br />

and the former is still recognised as<br />

the ‘<strong>of</strong>ficial’ capital <strong>of</strong> the State <strong>of</strong><br />

Israel by the United Nations. This<br />

divisive situation remains one <strong>of</strong><br />

the major points <strong>of</strong> conflict in the<br />

Israeli-Palestinian relationship. <strong>The</strong><br />

Israeli Parade in 1968 after 6 day war<br />

Palestinian people, the majority<br />

<strong>of</strong> whom are citizens <strong>of</strong> Israel,<br />

desire an independent Muslim<br />

state with East Jerusalem as its<br />

capital. <strong>The</strong> Jewish state <strong>of</strong> Israel<br />

is unwilling, both on religious and<br />

strategic grounds, to countenance<br />

any division <strong>of</strong> the city.<br />

Whilst access to the<br />

Western Wall is now<br />

open to Jews, the Temple<br />

Mount remains a Muslim<br />

holy place and any plans<br />

by the Jewish orthodox<br />

to restore sacrificial<br />

worship on the site seems<br />

unlikely to be fulfilled<br />

in any conceivable<br />

future. <strong>The</strong> Christian<br />

presence, based around<br />

different sites, remains stable but<br />

small and politically insignificant.<br />

Since Bethlehem found itself in<br />

Palestinian-administrated territory,<br />

its Christian population has<br />

decreased significantly and this<br />

trend seems likely to continue.<br />

Today, Jerusalem lives in a tense<br />

peace, a secular capital as well<br />

as a Holy City. It has grown<br />

considerably in terms <strong>of</strong> size and<br />

population since the establishment<br />

<strong>of</strong> the State <strong>of</strong> Israel. For many <strong>of</strong><br />

its citizens, the religious claims to<br />

the city function as an annoyance<br />

and a barrier to a lasting political<br />

peace. Yet for the religious its<br />

stones bear the footprints <strong>of</strong> priests,<br />

prophets, and kings. For them,<br />

Jerusalem is not any other city,<br />

and never could be. <strong>The</strong> Mount <strong>of</strong><br />

Olives, outside the old walled city,<br />

is covered with separate cemeteries<br />

belonging to the Jewish, Christian,<br />

and Islamic faiths. <strong>The</strong> graves are<br />

orientated to the east, the direction<br />

from which the Messiah will enter<br />

the City at the end <strong>of</strong> days.<br />

For the three faiths for whom<br />

Jerusalem is sacred, its history is<br />

not yet complete. Just as the Rock<br />

Palestinian and Israeli Protestors protest outside Hebrew University<br />

“<strong>The</strong> most holy spot on earth is Syria; the<br />

most holy spot in Syria is Palestine; the most<br />

holy spot in Palestine is Jerusalem; the most<br />

holy spot in Jerusalem is the Mountain; the<br />

most holy spot in Jerusalem is the place <strong>of</strong><br />

worship, and the most holy spot in the place<br />

<strong>of</strong> worship is the Dome.”<br />

Thawr ibn Yazid, c770AD<br />

<strong>of</strong> Mount Zion came to be believed<br />

to be the place where God had laid<br />

the foundations <strong>of</strong> the world, so to<br />

Jerusalem is the place where this<br />

story will reach fulfilment. Despite<br />

the fractured, bloody, and violent<br />

history <strong>of</strong> the city it is Jerusalem<br />

that is looked to<br />

as an analogue<br />

<strong>of</strong> Heaven itself.<br />

<strong>The</strong> conclusion<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Bible sees<br />

the renewal <strong>of</strong> the<br />

world pouring forth<br />

from a transfigured<br />

Zion, “prepared as<br />

a bride, adorned for<br />

her husband” (Rev.<br />

21: 2b). Amidst the<br />

religious strife <strong>of</strong> the<br />

city, and the attempts to resolve it,<br />

it is vital to recall that it is this New<br />

Jerusalem that is being fought over.<br />

Adam Kendry read <strong>The</strong>ology at<br />

Oxford University and has taught<br />

at Ampleforth before becoming<br />

Head <strong>of</strong> Divinity and Philosophy<br />

at <strong>Ardingly</strong> <strong>College</strong>. He is an<br />

Anglican theologian and Sub-<br />

Lieutenant (RN) and about to<br />

join the Submarine Operations<br />

and Strategy Branch.<br />

5 6

<strong>The</strong> Capture <strong>of</strong><br />

Jerusalem, July 1099<br />

Axel Fithen<br />

This article tells the end <strong>of</strong> an incredible story and<br />

what was also an extraordinary journey. It all began<br />

in November 1095. Pope Urban II held a council <strong>of</strong><br />

the Church at Clermont in France where he discussed<br />

ordinary papal matters such as corruption within<br />

the church as well as the consequences <strong>of</strong> the King<br />

<strong>of</strong> France’s adultery. However, on the last day, Urban<br />

addressed thousands in the fields outside the town, to<br />

make an extraordinary speech. It sparked one <strong>of</strong> the<br />

greatest conflicts <strong>of</strong> the entire medieval period which<br />

saw its conclusion in the city <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem.<br />

“A grave report has come ...that a race absolutely<br />

alien to God...has invaded the land <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Christians...<strong>The</strong>y have either razed the churches<br />

<strong>of</strong> God to the ground or enslaved them to their<br />

own rites...<strong>The</strong>y cut open the navels <strong>of</strong> those they<br />

choose to torment...drag them around and flog<br />

them before killing them as they lie on the ground<br />

with all their entrails out...What can I say <strong>of</strong> the<br />

appalling violation <strong>of</strong> women On whom does the<br />

task lie <strong>of</strong> avenging this, if not on you...Take the<br />

road to the Holy Sepulchre, rescue that land and<br />

....Take this road for the remission <strong>of</strong> your sins,<br />

assured <strong>of</strong> the unfading glory <strong>of</strong> the kingdom<br />

<strong>of</strong> heaven.”<br />

When Pope Urban came to a close the crowd erupted<br />

into a religious frenzy chanting “Deus vult! Deus<br />

vult!” (“God wills it! God wills it!”)<br />

In this powerful speech, Pope Urban II launched what<br />

would become the First Crusade. Four years later<br />

having marched through Europe to Constantinople,<br />

the capital <strong>of</strong> the Byzantine empire and then on<br />

through Anatolia into the holy land, fighting hard<br />

battles at Nicaea (May 1097,) Dorylaeum (June<br />

1097,) Edessa (mid-1097 to early 1098) and Antioch<br />

(1097-98,) the crusader contingents <strong>of</strong> approximately<br />

1,300 knights and 12,500 footmen, reached Jerusalem<br />

on 7th <strong>of</strong> June 1099. <strong>The</strong>se men had travelled to<br />

the centre <strong>of</strong> their world under the Papal promise <strong>of</strong><br />

remission for all their sins. <strong>The</strong>y reached the sacred<br />

city, where Christ had been crucified, and indeed for<br />

many <strong>of</strong> these warrior pilgrims, it was a moment <strong>of</strong><br />

extreme piety. Tancred, the nephew <strong>of</strong> the founder<br />

<strong>of</strong> the principality <strong>of</strong> Antioch, Bohemond, saw<br />

Jerusalem from the Mount <strong>of</strong> Olives and sank to his<br />

knees saying he would gladly sacrifice his life for the<br />

opportunity to kiss the church <strong>of</strong> the Holy Sepulchre,<br />

the site <strong>of</strong> Christ’s crucifixion.<br />

On nearing the city the Crusader force surrounded<br />

it, concentrating their forces on two main sections.<br />

Raymond <strong>of</strong> Saint-Gilles took a force to the southwestern<br />

corner, while the remaining force, under<br />

Godfrey <strong>of</strong> Bouillon and Tancred, laid siege to the<br />

north-western district <strong>of</strong> the city. Early attacks were<br />

unsuccessful, especially in the north-western district<br />

which was defended by a double wall <strong>of</strong> colossal<br />

height. An attack on the 13th June failed due to<br />

a shortage <strong>of</strong> wooden ladders to scale the city walls.<br />

However, just as the Crusaders’ journey appeared<br />

to have fatally stalled, deliverance was at hand, just<br />

as it had been so many times over the previous four<br />

years. Firstly, two Genoese ships arrived at the port<br />

<strong>of</strong> Jaffa supplying timber and other materials to<br />

build siege engines. Tancred himself is credited with<br />

solving the problem <strong>of</strong> the lack <strong>of</strong> other supplies. It<br />

seems while searching for a place to seek relief as a<br />

result <strong>of</strong> suffering from a case <strong>of</strong> terrible diarrhoea,<br />

he discovered a cave filled with timber. This was <strong>of</strong><br />

course seen as divine intervention and a sign <strong>of</strong><br />

God’s will that the city should fall to the Christians<br />

and the atrocities committed by the Muslims should<br />

be avenged.<br />

Top: 1st Crusade<br />

Above top: siege <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem during the first crusade<br />

Bottom: 1st Crusaders - show the crusaders the way to the Jerusalem<br />

Above: 1099 Siege <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem<br />

7 8

Meanwhile the Crusaders were becoming increasingly<br />

restless for a resolution to this siege. Hunger,<br />

exhaustion and more importantly, news had arrived<br />

that an army <strong>of</strong> muslim reinforcements had been sent<br />

to break the siege. <strong>The</strong> Crusaders desperately needed<br />

a swift conclusion to the siege and on the night <strong>of</strong><br />

the 13th <strong>of</strong> July an answer was found. Under cover<br />

<strong>of</strong> darkness Duke Godfrey ordered his siege tower to<br />

be taken apart and reconstructed a mile to the east<br />

<strong>of</strong> its current position. Godfrey had discovered a less<br />

well defended section <strong>of</strong> the city’s walls with a flatter<br />

approach for the siege tower. It was perfect.<br />

<br />

Was the ability <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem’s<br />

rulers the main reason for the<br />

survival <strong>of</strong> the estates during<br />

the twelfth century<br />

Anastasia Harrington<br />

Map <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem from 1099<br />

Route <strong>of</strong> the First Crusaders’<br />

Two mighty siege towers were constructed by the<br />

crusaders, each about fifty feet tall and built on<br />

wheeled platforms complete with a mighty battering<br />

ram. During their construction, one man was said to<br />

have had a vision <strong>of</strong> the spiritual leader <strong>of</strong> the crusade,<br />

Adhemar <strong>of</strong> Le Puy, who had died at Antioch the<br />

previous year. In the vision Adhemar had advised the<br />

warriors <strong>of</strong> Christendom to stage a procession to the<br />

Mount <strong>of</strong> Olives, the place where Christ ascended<br />

into heaven. <strong>The</strong> leaders <strong>of</strong> the crusading contingents,<br />

fearful <strong>of</strong> disobeying God’s wishes, duely obliged.<br />

Barefoot, taking crosses and relics, thousands <strong>of</strong><br />

crusaders ventured down the valley <strong>of</strong> Jehoshaphat<br />

praying and seeking God’s favour.<br />

At dawn the following morning Godfrey launched<br />

his attack. <strong>The</strong> crusaders managed to breach the wall,<br />

however they encountered fierce resistance from<br />

the besieged army who may have used Greek fire, a<br />

naptha based substance, which cannot be extinguished<br />

by water. Around midday the crusaders managed to<br />

force the Muslim defenders to flee and abandon their<br />

defensive positions on the wall immediately in front<br />

<strong>of</strong> the siege tower. At this moment Godfrey ordered<br />

his siege tower to lower its bridge onto the wall. As<br />

Crusaders poured into the city, Muslim resistance<br />

quickly collapsed. Thousands <strong>of</strong> Muslims, Jews,<br />

Christians, men, women and children were massacred.<br />

William <strong>of</strong> Tyre, writing around the 1180’s described<br />

the slaughter:<br />

‘Everywhere lay fragments <strong>of</strong> human bodies,<br />

and the very ground was covered with the blood<br />

<strong>of</strong> the slain. Still more dreadful was it to gaze<br />

upon the victors themselves, dripping with blood<br />

from head to foot’<br />

<strong>The</strong> Kingdom <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem was founded through<br />

this barbarity and it would stand for nearly a century<br />

until Saladin’s rise to power and political infighting<br />

among the Crusader kingdoms would see its fall to<br />

the Muslims in 1187. <strong>The</strong> events <strong>of</strong> that siege have<br />

lived long in the consciousness <strong>of</strong> Muslims and<br />

Christians ever since. But they have taken on a greater<br />

importance still. <strong>The</strong>y have shaped more than just the<br />

heritage <strong>of</strong> those that continue to live there. <strong>The</strong>y have<br />

become part <strong>of</strong> the complicated political tapestry that<br />

is Jerusalem, Israel and the Middle East.<br />

It can be argued that the survival <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Crusader Kingdom <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem during the<br />

twelfth century was due to the ability <strong>of</strong> its<br />

rulers; however there were other factors that<br />

enabled its survival. <strong>The</strong>se included the relative<br />

disunity and weakness <strong>of</strong> real and potential<br />

enemies, the support from western powers,<br />

and the Crusaders’ military capabilities.<br />

In July 1099 Jerusalem was conquered by<br />

the Crusaders and established as a Crusader<br />

Kingdom. Between 1101 and 1110 the Crusader<br />

estates in the region were extended as the<br />

Principality <strong>of</strong> Antioch and the County <strong>of</strong> Tripoli;<br />

these extended the geographical area under<br />

Crusader control in to a continuous line along<br />

the eastern coast <strong>of</strong> the Mediterranean from<br />

south <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem. Even so, the Crusader<br />

states were a long way from potential western<br />

allies, with long and uncertain supply lines.<br />

This meant that the rulers had to be able<br />

administrators and diplomats to ensure that<br />

they could marshal limited resources and create<br />

alliances to counter these problems, as well as<br />

being effective military leaders to repel enemy<br />

attacks, expand and consolidate territorial<br />

gains. This required exceptional leadership and<br />

as Fulcher <strong>of</strong> Chartres noted when Baldwin I<br />

was crowned, “the King would need energy to<br />

conquer the Muslims in battle, or...compel them<br />

to make peace.” <strong>The</strong> ability <strong>of</strong> Baldwin I shows<br />

how an effective ruler was able to ensure the<br />

survival <strong>of</strong> the Kingdom <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem during the<br />

early part <strong>of</strong> the twelfth century.<br />

King Baldwin II<br />

During his reign, Baldwin I (1100-1118)<br />

continued the process <strong>of</strong> consolidating territorial<br />

gains and securing supply routes across the<br />

Mediterranean Sea with the taking <strong>of</strong> coastal<br />

cities; with Acre falling to the Christians in 1104<br />

and Beirut and Sidon were taken in 1110, (with<br />

help from a large force <strong>of</strong> Norwegian Crusaders<br />

under King Sigurd). <strong>The</strong> armies <strong>of</strong> the Kingdom<br />

<strong>of</strong> Jerusalem fought annual battles against the<br />

Egyptians in the South and the Damascenes,<br />

9 10

when the Damascenes were not allied with<br />

the Frankish Crusaders against the Muslims <strong>of</strong><br />

Northern Syria, who were a common enemy.<br />

Additionally, Baldwin I’s reputation as a ruler<br />

was enhanced by his construction <strong>of</strong> Montreal<br />

Castle in Transjordan, and by extending Crusader<br />

command <strong>of</strong> the region east <strong>of</strong> the River Jordan<br />

and the Dead Sea, down to the Red Sea port<br />

<strong>of</strong> Eilat. This resulted in a valuable increase<br />

in revenue as traders between Damascus to<br />

Egypt had to pay taxes to traverse the area.<br />

As a monarch he held his nobles in close<br />

control for much <strong>of</strong> his reign until he died in<br />

April 1118. Such successful military action, with<br />

the resulting increase in revenue, the ability<br />

to establish a working relationship with new<br />

allies and an enemy against a common enemy<br />

required great skill. Together with establishing<br />

a more cohesive Kingdom and improving the<br />

supply routes to Jerusalem via the ports, may be<br />

why Baldwin I’s rule is regarded as successful.<br />

<strong>The</strong> reputation <strong>of</strong> strong Crusader leadership<br />

by the Kings <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem was reinforced by<br />

Baldwin II when he restored control and order in<br />

Antioch after the Field <strong>of</strong> Blood 1119, although<br />

this reduced Crusader resources. This reputation<br />

for strong and successful military leadership<br />

may have inspired continued support from<br />

European powers and individuals to continue<br />

on a Crusade. Baldwin II also continued a policy<br />

<strong>of</strong> local alliances and diplomacy to reinforce<br />

regional support.<br />

This shows that the early Crusaders may<br />

have followed a pragmatic social practice<br />

that reinforced the ability <strong>of</strong> the Kingdom to<br />

survive. Although the Franks dominated the<br />

regions they conquered, imposing hierarchies<br />

<strong>of</strong> power with themselves at the top, the<br />

societies they initiated depended on employing<br />

the local population. Lack <strong>of</strong> manpower and<br />

military resources in the early days did not<br />

make segregation or discrimination a practical<br />

decision, rather integration proved crucial to<br />

survival. Frankish authorities tolerated racial<br />

and religious diversity in the ports <strong>of</strong> Acre,<br />

Tripoli and Tyre because the value <strong>of</strong> the<br />

indigenous population to the political economy<br />

was understood. Baldwin II’s marriage created<br />

a union with the Armenian Church’s patriarchs.<br />

While Baldwin’s example may have been a<br />

diplomatic success and set an example to<br />

others, following the Field <strong>of</strong> Blood, relations<br />

between the religious communities’ hardened<br />

and integrated marriages were banned. A church<br />

council at Nablus early in 1120 forbade sexual<br />

relations between Christians and Muslims, so<br />

undermining the example set by Baldwin II<br />

and potentially reducing the influence <strong>of</strong> future<br />

rulers. Such divisions in society probably robbed<br />

the Crusader states <strong>of</strong> a potential workforce,<br />

which in turn meant it was not economically<br />

self-sufficient and became dependent on<br />

external supplies.<br />

Within the Crusader States, the early leaders<br />

<strong>of</strong> each estate showed strong allegiance to<br />

the ruler <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem and support for new<br />

campaigns, so that they were able to make<br />

up for the shortage <strong>of</strong> manpower by acting as<br />

a unified force. For example, despite having<br />

conquered Jerusalem and Caesarea, a new<br />

Crusade was summoned to conquer Antioch,<br />

300 miles away. Many deserters <strong>of</strong> the first<br />

Crusade, such as Stephen de Blois, came<br />

back on this Crusade, reaching its destination<br />

in 1102. This Crusade shows the importance<br />

that the rulers gave to keeping state to state<br />

communication secure and protect the physical<br />

route between Jerusalem and other Crusader<br />

states to allow swift movement between them.<br />

Nonetheless, this seems to have <strong>of</strong>ten been a<br />

local responsibility as each estate had its own<br />

defences to keep overland communication<br />

routes open with its neighbours and defend its<br />

borders. Successful, mutual support from the<br />

rulers <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem reinforced their reputation<br />

and may have strengthened the internal<br />

allegiances, so enabling more effective rule.<br />

<strong>The</strong> death <strong>of</strong> Baldwin II in August 1131 marked<br />

the end <strong>of</strong> the first generation <strong>of</strong> Crusader<br />

rulers and the initial passion that first drove<br />

the Crusaders. Without a male heir this gave<br />

rise to different factions jostling for power<br />

and increasing disunity within the Crusader<br />

states. To try to prevent this, Baldwin II named<br />

his successor, Count Fulk V <strong>of</strong> Anjou, and his<br />

acceptance demonstrated the desire to maintain<br />

Kerak Castle<br />

a strong continuous line <strong>of</strong> leaders within the<br />

main kingdom itself and an ongoing loyalty to<br />

protect the Holy City from the ‘infidel’.<br />

Although early Muslim weakness and disunity<br />

meant that enemy threats were not too<br />

problematic, frequent skirmishes, and border<br />

raids meant that the Crusader kingdoms had<br />

to develop from a politically based society to<br />

a military one. Additionally, the Muslim enemy<br />

was becoming increasingly unified under the<br />

concept <strong>of</strong> jihad, so that by August 1st 1119 the<br />

forces <strong>of</strong> the first Crusade were defeated at the<br />

battle <strong>of</strong> Sarmada, in the ‘Field <strong>of</strong> Blood’ by Turks<br />

under Tel-Danith. However, the Crusaders under<br />

Baldwin II were able to defeat the advancing<br />

Turks two weeks later thus indicating that the<br />

King’s leadership and tactics were still strong<br />

enough to fight <strong>of</strong>f the enemy despite the<br />

previous losses against the other estate leaders.<br />

<strong>The</strong> defeat <strong>of</strong> Roger <strong>of</strong> Antioch and the wiping<br />

out <strong>of</strong> the Frankish army at the Field <strong>of</strong> Blood<br />

in 1119 forced the Crusader states to realise<br />

the necessity <strong>of</strong> developing stronger, more<br />

effective military defences against the Muslim<br />

fighters. As a counter to this threat, new military<br />

orders were founded, under the radical new<br />

concept <strong>of</strong> warrior monks, and castles, built<br />

as strategic outposts, grew in importance<br />

throughout the twelfth century, paralleling the<br />

rise <strong>of</strong> Muslim threat. <strong>The</strong> warrior monks eased<br />

the drastic lack <strong>of</strong> manpower but did not solve<br />

the problem completely. <strong>The</strong>se castles were<br />

primarily defensive and designed to strike fear<br />

and caution into the enemy, but due to the lack<br />

<strong>of</strong> manpower they were not <strong>of</strong> great military<br />

value. <strong>The</strong>y were <strong>of</strong>ten built in remote areas and<br />

lack <strong>of</strong> manpower meant that commanders were<br />

faced with either abandoning the castles to<br />

fight the enemy or withdrawing into the castles<br />

and facing a less than promising siege. Muslim<br />

defences however were urban which made<br />

their cities difficult to breach. However, the<br />

castles did help to secure trade routes, provided<br />

centres <strong>of</strong> administration and a concentration <strong>of</strong><br />

warriors that could launch raids or attacks when<br />

necessary. Jonathan Philips believed they had<br />

a significant advantage, “...key to holding onto<br />

territory was the control <strong>of</strong> castles and fortified<br />

sites...” This shows that the military order played<br />

another vital role alongside the previous one<br />

<strong>of</strong> links to the west, showing that there were<br />

other reasons for the survival <strong>of</strong> the kingdom <strong>of</strong><br />

Jerusalem besides its rulers.<br />

Despite the support that the Crusaders were<br />

willing to give to the leaders in Jerusalem,<br />

the struggling kingdom was also dependent<br />

on vital western support from the beginning.<br />

This support was sometimes conditional upon<br />

achieving the objectives <strong>of</strong> other rulers and may<br />

have served to undermine the survival <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Kingdom <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem. <strong>The</strong> 1108 campaign<br />

created a major development in the crusading<br />

idea <strong>of</strong> a Holy War against the supposed infidel<br />

and this weakened support from the Byzantines<br />

to the Crusaders. As the battle to overtake<br />

the Byzantines in Durazzo failed, Bohemond<br />

became an imperial vassal to Emperor Alexius.<br />

This crusade again demonstrates how help<br />

from the west was valued by the Kingdom <strong>of</strong><br />

Jerusalem in upholding their Holy City; however<br />

it also demonstrates the uneven and distrustful<br />

relationship between some Crusaders and the<br />

Byzantines that undermined the effectiveness<br />

<strong>of</strong> the rulers <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem to make and enforce<br />

11 12

obust alliances which could not be undone by<br />

western powers or other Crusaders following<br />

their own agendas.<br />

Support <strong>of</strong>ten came at a price that meant that<br />

some areas were outside the authority <strong>of</strong> the<br />

rulers <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem. For example, when Venetian<br />

fleets assisted with the capture <strong>of</strong> Sidon and<br />

Syrian coastal cities, the Venetians demanded as<br />

payment for their assistance to be the virtually<br />

autonomous owners <strong>of</strong> parts <strong>of</strong> the Holy Land<br />

and this was granted through the Pactum<br />

Warmundi. By having to surrender authority to a<br />

‘foreign power’ within the state suggests that the<br />

Crusaders were dependent on external support<br />

to maintain and expand their territory and<br />

their limited options available may have forced<br />

them to part with valuable prizes to secure that<br />

support. <strong>The</strong> development <strong>of</strong> these coastal cities<br />

opened up trade routes, strengthening links to<br />

the West and the Byzantine Empire, establishing<br />

thriving markets dependent on the Italian city<br />

state trade, e.g. the Venetians owned one third<br />

<strong>of</strong> Tyre. Arguably, the success <strong>of</strong> these trade<br />

cities helped the survival <strong>of</strong> the Kingdom <strong>of</strong><br />

Jerusalem by increasing economic activity, but<br />

by representing a ‘foreign power’ within its state,<br />

it may be argued that the kingdom was further<br />

fragmented and left the rulers <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem with<br />

another powerful group within its borders whose<br />

demands they had to consider.<br />

Having regional, individual authorities ruling<br />

areas within the Crusader states meant that the<br />

Crusaders were not always united. Consequently,<br />

the rulers <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem were <strong>of</strong>ten faced with<br />

dealing with internal issues as well as external<br />

threats. Indeed civil war threatened or broke out<br />

four times after 1130.<br />

This shows that the Crusader states were<br />

dependent on external supplies and support for<br />

their survival and it was not always within their<br />

power to control it. This also suggests that the<br />

Crusaders were too small and fragmented a<br />

force to ensure the survival <strong>of</strong> the Kingdom.<br />

While economic success may have created trade<br />

links with Italian city states, there is no evidence<br />

that this wealth enabled the Crusader states to<br />

develop economic independence. However, the<br />

effective military leadership and ability to inspire<br />

further action seems to have ensured the early<br />

survival <strong>of</strong> the Kingdom. Although it is apparent<br />

that the leader <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem had a vital impact<br />

and contribution to the survival <strong>of</strong> the kingdom<br />

during the twelfth century it is also clear that the<br />

other factors such as the support from the west<br />

and initial weakness <strong>of</strong> the enemy played a vital<br />

part, suggesting that the leaders were not the<br />

only reason.<br />

Map <strong>of</strong> the Frankish states<br />

Sources<br />

T. Asbridge, <strong>The</strong> Crusades: <strong>The</strong> War for the Holy Land, Simon & Schuster Ltd (2012)<br />

J. Phillips, A Modern <strong>History</strong> <strong>of</strong> the Crusades, Vintage (2010)<br />

Just short <strong>of</strong> ninety years<br />

after the crusading force <strong>of</strong><br />

Pope Urban II’s iconic first<br />

crusade captured the Holy<br />

City <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem from the<br />

Islamic forces that occupied<br />

it, Saladin, the Islamic ‘Holy<br />

warrior’, was to re-take the<br />

city that was the centre <strong>of</strong> the<br />

medieval religious world.<br />

1187,<br />

<strong>The</strong> Battle <strong>of</strong> Hattin and<br />

the Capture <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem<br />

Saladin had previously<br />

attempted to attack the<br />

Kingdom <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem in the<br />

autumn <strong>of</strong> 1177, however due<br />

to the efforts <strong>of</strong> Baldwin IV,<br />

its famous Leper King, he had<br />

been defeated ignominiously<br />

at the battle <strong>of</strong> Mont Gisard.<br />

On this return attack ten years<br />

later, Saladin had with him<br />

over 42,000 men, described<br />

by a contemporary eyewitness<br />

as a pack <strong>of</strong> ‘old wolves [and]<br />

rending lions’. <strong>The</strong> opposition<br />

that Saladin faced was a broken<br />

and disjointed kingdom. With<br />

the death <strong>of</strong> the former king<br />

Baldwin IV in 1185 clear lines<br />

<strong>of</strong> leadership had broken down<br />

and the significantly weakened<br />

John Gibson<br />

state was rallied under the<br />

previous regent and newly<br />

crowned, Guy <strong>of</strong> Lusignan.<br />

Odds had shifted decidedly<br />

in favour <strong>of</strong> the Islamic forces.<br />

Saladin had only to defeat the<br />

crusader army and the Holy City<br />

was his. Or so it seemed…<br />

<strong>The</strong> decisive battle in the<br />

re-capture <strong>of</strong> Jerusalem was<br />

not fought at, or particularly<br />

near to, the Holy City itself.<br />

Saladin instead drew out the<br />

Crusader army to Hattin where<br />

the final blow to the crusader<br />

kingdoms was to be delivered.<br />

Taking the fortress <strong>of</strong> Tiberias,<br />

Count Raymond <strong>of</strong> Tripoli’s<br />

personal fortress, on the 2nd <strong>of</strong><br />

July Saladin had ‘laid his trap’<br />

(Asbridge) for the crusaders, as<br />

Raymond’s wife was trapped at<br />

Tiberias at the time. Raymond<br />

remained, despite the potential<br />

‘<strong>The</strong> devil seduced [Guy] into doing the<br />

opposite <strong>of</strong> what he had in mind and made<br />

to seem good to him what was not his real<br />

wish and intention. So he left the water<br />

and set out towards Tiberias… through<br />

pride and arrogance’.<br />

for his loss, calm, and advised<br />

Guy to refrain from engaging<br />

the Islamic force claiming, it<br />

would break apart like so many<br />

before it. It was to be Reynald<br />

<strong>of</strong> Châtillon and the Templar<br />

master Gerard <strong>of</strong> Ridefort<br />

13 14

who <strong>of</strong>fered up an opposing<br />

view. Reynald advised Guy to<br />

disregard the count’s advice<br />

and take the battle to Saladin.<br />

Asbridge suggests that despite<br />

the council <strong>of</strong> those around<br />

him it most likely Guy’s own<br />

experience four years earlier<br />

that informed his decision that<br />

night. Guy had been presented<br />

with a near identical decision in<br />

1183 and had eschewed battle<br />

with Saladin, granting him only<br />

derision and demotion. <strong>The</strong><br />

decision, however, to advance<br />

toward Tiberias was believed<br />

fatal by even Saladin, as he<br />

wrote in a letter immediately<br />

after the battle:<br />

‘<strong>The</strong> devil seduced [Guy] into<br />

doing the opposite <strong>of</strong> what<br />

he had in mind and made to<br />

seem good to him what was<br />

not his real wish and intention.<br />

So he left the water and set<br />

out towards Tiberias… through<br />

pride and arrogance’.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Crusaders marched forth<br />

from Saffuriya on the morning<br />

<strong>of</strong> 3rd July and left behind them<br />

there a sure supply <strong>of</strong> water,<br />

which was to be the downfall <strong>of</strong><br />

the army in the battle to come.<br />

<strong>The</strong> army would have been a<br />

menacing sight in full march,<br />

as one eye witness states ‘they<br />

came, wave after wave… the<br />

air stank, the light was dimmed<br />

[and] the desert was stunned<br />

by their advance’. By noon the<br />

army had reached the small<br />

village <strong>of</strong> Turan, where they<br />

attempted to replenish their<br />

supplies <strong>of</strong> water. However<br />

the small village spring was<br />

not sufficient for the many<br />

thousands assembled and the<br />

army was forced to continue<br />

towards the sea <strong>of</strong> Galilee<br />

during the remaining heat <strong>of</strong><br />

the day. At day’s end, Guy<br />

made the decision to make<br />

camp in an entirely waterless,<br />

indefensible position; a move<br />

that played directly into the<br />

hands <strong>of</strong> Saladin.<br />

On the following day, 4th <strong>of</strong><br />

July, the Battle <strong>of</strong> Hattin took<br />

place. <strong>The</strong> Crusaders had been<br />

surrounded by the Islamic forces<br />

overnight and were at the mercy<br />

<strong>of</strong> Saladin. <strong>The</strong> Islamic Holy<br />

Warrior ordered his troops to set<br />

fire to the scrubs surrounding<br />

the crusaders, exacerbating the<br />

immense dehydration already<br />

suffered by the Crusaders.<br />

This, <strong>of</strong> course, was not an<br />

issue for the well supplied<br />

Islamic troops. In the following<br />

hours, the Islamic archers and<br />

horsemen tore the Crusaders<br />

apart, culminating in Guy’s<br />

final heroic stand at the Horns<br />

<strong>of</strong> Hattin with the relic <strong>of</strong> the<br />

True Cross. Guy’s plan was to<br />

strike at the heart <strong>of</strong> the Islamic<br />

force, Saladin himself, with his<br />

heavier and more powerful<br />

force <strong>of</strong> knights. However,<br />

despite twice charging over the<br />

Horns <strong>of</strong> Hattin the crusaders<br />

were overrun by Islamic forces<br />

and day was won by Saladin.<br />

<strong>The</strong> army <strong>of</strong> the kingdom <strong>of</strong><br />

Jerusalem was destroyed and<br />

the King and their main relic,<br />

the true cross, captured.<br />

Having crushed the<br />

accumulated crusader forces<br />

at the battle <strong>of</strong> Hattin very few<br />

were left to defend the Holy<br />

Land, one eyewitness claimed<br />

that only two knights and their<br />

retainers were left in defence<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Holy City when Saladin<br />

arrived. Almost immediately<br />

after the battle the citadel at<br />

Tiberius surrendered and a<br />

week later the coastal city <strong>of</strong><br />

Acre followed suit. Over the<br />

following weeks and months<br />

Saladin focused on claiming<br />

the remainder <strong>of</strong> Palestine’s<br />

coastal settlements. By<br />

September 1187 Saladin had<br />

only one intention, the capture<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Holy City itself.<br />

Saladin took the Holy City<br />

formally on 2nd <strong>of</strong> October,<br />

mirroring the actions <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Islamic prophet Mohamed. In<br />

contrast to the actions <strong>of</strong> the<br />

crusaders some ninety years<br />

previously Saladin allowed<br />

Christians to buy their freedom<br />

for up to a month after the<br />

capture <strong>of</strong> the city, ten dinars<br />

for a man, five for a woman and<br />

one for a child. After the month<br />

had ended the remainder <strong>of</strong><br />

Christians were to be rounded<br />

up and enslaved, however<br />

this course <strong>of</strong> action seems<br />

charitable in contrast to the<br />

‘bloodbath’ which the original<br />

crusaders brought to the city<br />

in 1099. And thus, in reality,<br />

ended the era <strong>of</strong> the Kingdom<br />

<strong>of</strong> Jerusalem although it’s King<br />

and his few remaining citadels<br />

would hold out for many years<br />

to come. Nonetheless, Christian<br />

domination and control <strong>of</strong><br />

Jerusalem was at an end and<br />

this fateful year, 1187, witnessed<br />

the sudden collapse <strong>of</strong> Christian<br />

(and certainly catholic) power in<br />

the Middle East.<br />

This double arm gold reliquary cross was<br />