RA 00110.pdf - OAR@ICRISAT

RA 00110.pdf - OAR@ICRISAT

RA 00110.pdf - OAR@ICRISAT

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

in tests conducted by ICRISAT on farmers' fields.<br />

Grain yield responses were particularly low in the<br />

Sahel region where agroclimatic conditions essentially<br />

limit farmers to millet production (Table 2).<br />

Moreover, in the Sudan savanna, where farmers<br />

have wider options to allocate their scarce fertilizer<br />

to either sorghum or millet, the yield response for<br />

millet was approximately two-thirds of the sorghum<br />

response.<br />

The low absolute response in the principal millet<br />

producing zone, and the low relative response of<br />

millet compared to sorghum (and other cereals) in<br />

the transition zone create powerful economic disincentives<br />

against the use of fertilizer on millet. In the<br />

ICRISAT farmers' tests just cited, average returns to<br />

the recommended fertilizer dose when applied to<br />

local millet cultivars in the Sahel Zone were consistently<br />

negative, and average returns in the Sudan<br />

savanna were only 10% (Table 2).<br />

It is important to note that ICRISAT farmer tests<br />

evaluating the economics of phosphorus fertilizers<br />

applied to millet in the Sahel Zone of Niger have<br />

produced higher returns than tests in Burkina Faso.<br />

Differences are due to higher millet grain prices in<br />

Niger, and because the most available and currently<br />

recommended fertilizer in Burkina Faso is imported<br />

primarily for use on cotton and is therefore not an<br />

efficient formula for millet.<br />

A further analysis of returns over a range of fertilizer<br />

doses has shown that at all doses, average financial<br />

returns were highest in the more humid Guinean<br />

Zone and declined systematically in more arid areas,<br />

becoming marginal or negative in the Sahelian sites<br />

(ICRISAT 1984, pp. 313-314). The risk of financial<br />

losses followed a similar south-north pattern. Moreover,<br />

when sorghum was compared to millet in the<br />

Sudan transition zone, risks were consistently lower<br />

and financial returns to fertilizer higher. Finally, at<br />

real economic prices (subsidy removed), complex<br />

fertilizer would be an attractive investment only in<br />

the southern zones when applied to sorghum at onehalf<br />

the recommended rate, and urea would be economic<br />

when applied to sorghum but not to millet in<br />

the Sahel and Sudanian Zones.<br />

In short, following production efficiency criteria<br />

alone, policymakers at the national level would concentrate<br />

fertilizer use in the northern Guinea savanna<br />

zone, where millet area is relatively unimportant,<br />

and limit use in the Sahel Zone where millet dominates.<br />

At the farm level, where farmers have the<br />

option, priority for fertilizer use would be given to<br />

sorghum (or to other relatively more responsive<br />

crops) well before millet. These conclusions become<br />

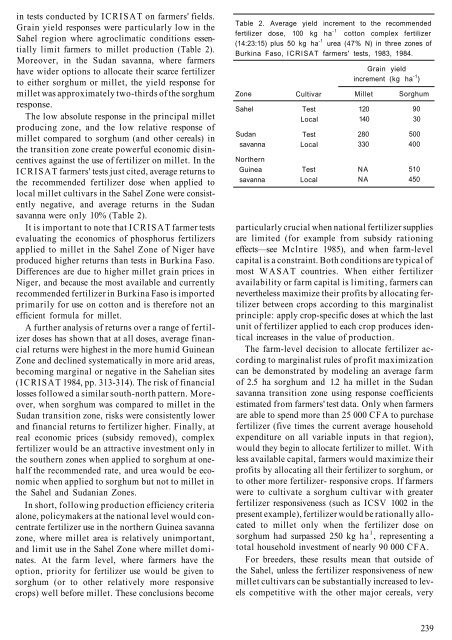

Table 2. Average yield increment to the recommended<br />

fertilizer dose, 100 kg ha -1 cotton complex fertilizer<br />

(14:23:15) plus 50 kg ha -1 urea (47% N) in three zones of<br />

Burkina Faso, ICRISAT farmers' tests, 1983, 1984.<br />

Zone<br />

Sahel<br />

Sudan<br />

savanna<br />

Northern<br />

Guinea<br />

savanna<br />

Cultivar<br />

Test<br />

Local<br />

Test<br />

Local<br />

Test<br />

Local<br />

Grain yield<br />

increment (kg ha -1 )<br />

Millet<br />

120<br />

140<br />

280<br />

330<br />

NA<br />

NA<br />

Sorghum<br />

90<br />

30<br />

500<br />

400<br />

510<br />

450<br />

particularly crucial when national fertilizer supplies<br />

are limited (for example from subsidy rationing<br />

effects—see Mclntire 1985), and when farm-level<br />

capital is a constraint. Both conditions are typical of<br />

most W A S A T countries. When either fertilizer<br />

availability or farm capital is limiting, farmers can<br />

nevertheless maximize their profits by allocating fertilizer<br />

between crops according to this marginalist<br />

principle: apply crop-specific doses at which the last<br />

unit of fertilizer applied to each crop produces identical<br />

increases in the value of production.<br />

The farm-level decision to allocate fertilizer according<br />

to marginalist rules of profit maximization<br />

can be demonstrated by modeling an average farm<br />

of 2.5 ha sorghum and 1.2 ha millet in the Sudan<br />

savanna transition zone using response coefficients<br />

estimated from farmers' test data. Only when farmers<br />

are able to spend more than 25 000 CFA to purchase<br />

fertilizer (five times the current average household<br />

expenditure on all variable inputs in that region),<br />

would they begin to allocate fertilizer to millet. With<br />

less available capital, farmers would maximize their<br />

profits by allocating all their fertilizer to sorghum, or<br />

to other more fertilizer- responsive crops. If farmers<br />

were to cultivate a sorghum cultivar with greater<br />

fertilizer responsiveness (such as ICSV 1002 in the<br />

present example), fertilizer would be rationally allocated<br />

to millet only when the fertilizer dose on<br />

sorghum had surpassed 250 kg ha 1 , representing a<br />

total household investment of nearly 90 000 CFA.<br />

For breeders, these results mean that outside of<br />

the Sahel, unless the fertilizer responsiveness of new<br />

millet cultivars can be substantially increased to levels<br />

competitive with the other major cereals, very<br />

239