All About Mentoring Spring 2011 - SUNY Empire State College

All About Mentoring Spring 2011 - SUNY Empire State College

All About Mentoring Spring 2011 - SUNY Empire State College

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

79<br />

could never serve the market that wanted<br />

mobility even at the expense of phone<br />

clarity or perfect coverage. So long as the<br />

old, existing, “sustaining” technologies<br />

were working well, could be improved for<br />

existing customers, and were profitable<br />

for the companies making them, there<br />

was no obvious incentive to try anything<br />

fundamentally different. And since the new<br />

“disruptive” technologies were usually<br />

demonstrably inferior at the beginning, there<br />

was no incentive to worry about them when<br />

companies knew their existing products and<br />

processes were better.<br />

This was and is a mistake. Today we all<br />

know many people who do not even have<br />

landlines, or home stereos, or who buy<br />

only digital format books. Thus, disruptive<br />

technologies like Walkmen (now IPods!), cell<br />

phones and Kindles – even if many could<br />

show how inferior they were to the products<br />

they replaced – have outstripped their<br />

competitors in the marketplace.<br />

For a traditional firm, serving their<br />

traditional customers, making an existing<br />

product better seems like an obviously good<br />

choice. One knows one’s customers and<br />

what they “need.” One does not know as<br />

well, if at all, what noncustomers might<br />

want out of the product or service. It is<br />

not always impossible to find out, but it is<br />

definitely harder. Since these noncustomers<br />

are not buying the product or service, it<br />

also is harder to convince the marketing<br />

department to cater to them instead of<br />

catering to the people actually buying and<br />

using the existing product or service and<br />

improving it to meet their needs. That, as<br />

Christensen and his co-authors suggest,<br />

is one main reason why companies tend<br />

to concentrate on developing sustaining<br />

technologies rather than throwing those<br />

aside and focusing on disruptive ones. The<br />

payoff for developing and implementing<br />

disruptive technologies is not obvious, and<br />

competent managers miss out on sure-fire<br />

opportunities available with sustaining<br />

technologies at their peril.<br />

As Christensen and his co-authors pursue<br />

their analysis of why companies succeed and<br />

fail at adapting to market changes when<br />

new products are introduced, they have<br />

developed some central ideas about how<br />

companies should proceed to make success<br />

more likely. The main approach they take is<br />

through their analysis of resources, processes<br />

and values. As processes and values<br />

solidify into organizational culture, the<br />

organizational culture restricts the way that<br />

companies can identify new opportunities,<br />

take advantage of them, and evaluate their<br />

potential for successful implementation.<br />

If successful organizations want to<br />

implement sustaining technologies, they<br />

likely already have the structure in place<br />

to do it. (This is reminiscent of the old<br />

management adage, “you have the perfect<br />

organization to get the results you’re<br />

getting.”) On the other hand, developing<br />

and growing through disruption requires a<br />

very different approach. This can happen<br />

through acquiring or establishing a new<br />

organization/company that already focuses<br />

on disruptive technologies or services, or<br />

through setting up an entirely new unit<br />

that can operate more or less unimpeded<br />

by the larger organizational culture. From<br />

Christensen’s point of view, once a company<br />

incorporates the disruptive technology into<br />

an existing organizational system used to<br />

developing sustaining technologies, then<br />

the opportunities for growth from the<br />

disruption are doomed. 2<br />

Disruptions at <strong>Empire</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>College</strong><br />

It might be interesting to use the Christensen<br />

framework to examine <strong>Empire</strong> <strong>State</strong><br />

<strong>College</strong>. One could argue that <strong>Empire</strong> <strong>State</strong><br />

<strong>College</strong> developed a radically different<br />

type of organizational structure than had<br />

existed in “traditional” colleges. These<br />

included learning centers and areas of<br />

The payoff for developing<br />

and implementing<br />

disruptive technologies<br />

is not obvious, and<br />

competent managers<br />

miss out on sure-fire<br />

opportunities available<br />

with sustaining<br />

technologies at their peril.<br />

study instead of departments, assessment<br />

committees for individualized degrees,<br />

learning contracts as a new “course” form,<br />

and the like. The reorientation of education<br />

to privilege the student’s goals instead of<br />

the professor’s goals; rethinking the role<br />

of advising, mentoring and teaching; the<br />

individualization of entire degree program<br />

plans; and the developmental objectives of<br />

the narrative evaluations are examples of<br />

different, disruptive, processes and values.<br />

<strong>Empire</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>College</strong> was an ambitious<br />

effort to challenge many orthodoxies of<br />

traditional higher education. The college<br />

also sought to expand learning possibilities<br />

to new audiences of learners, responding to<br />

the “nonconsumption” of higher education<br />

by adult and other nontraditional students.<br />

One might call this a “disruption” of the<br />

existing, “sustaining,” trajectory of higher<br />

education.<br />

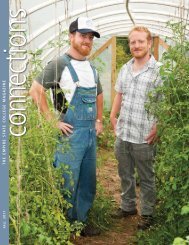

In order to optimize the disruptive potential<br />

for growth, from the start the college<br />

established a decentralized, noncampusbased,<br />

network of locations for students<br />

and mentors to work together. The<br />

college created a “center” and “unit”<br />

structure that maximized access for<br />

underserved populations (i.e., educational<br />

nonconsumers). The college also established<br />

venues like the Center for <strong>College</strong>wide<br />

Programs and the Center for Distance<br />

Learning (CDL). One could argue that<br />

CDL was an arena in which “disruption”<br />

took place only once individualized<br />

student learning became the norm and<br />

characterized general college culture. There<br />

were obviously many students who needed<br />

learning to happen in a flexible manner –<br />

flexible in time as well as in space. The<br />

Center for Distance Learning provided<br />

a way to do that through paper-based<br />

correspondence courses and then online<br />

learning. The disruption that CDL created<br />

was not, it seems, in altering the relationship<br />

between mentors and students; rather, it<br />

was disruption of the manner and timing<br />

of the learning. As the use of certain<br />

technologies (especially systems like Lotus<br />

Notes and Angel) became more taken<br />

for granted across the college, depending<br />

upon online learning strategies and<br />

platforms can now be considered sustaining<br />

and no longer innovative.<br />

suny empire state college • all about mentoring • issue 39 • spring <strong>2011</strong>