ARCH 84312

ARCH 84312

ARCH 84312

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Site, History, Type, and Allegory:<br />

The Poetics and Rhetoric of the Classical Tradition in Rome<br />

Arch. <strong>84312</strong><br />

Italian Classicism<br />

Tues./Thurs. 9:00—12:00<br />

Prof. David Mayernik<br />

SEMESTER THEMES<br />

[I ] t seems to be a lesson of history that the commonplace may be understood as a<br />

reduction of the exceptional, but that the exceptional cannot be understood by<br />

amplifying the commonplace.<br />

—Edgar Wind, Pagan Mysteries in the Renaissance, W.W. Norton, 1968, p. 238<br />

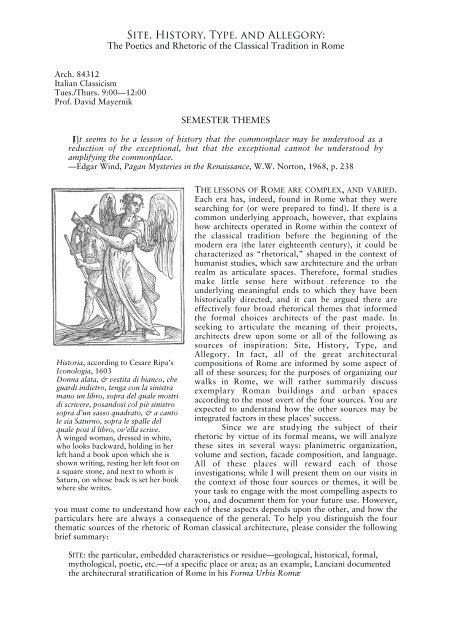

Historia, according to Cesare Ripa’s<br />

Iconologia, 1603<br />

Donna alata, & vestita di bianco, che<br />

guardi indietro, tenga con la sinistra<br />

mano un libro, sopra del quale mostri<br />

di scrivere, posandosi col piè sinistro<br />

sopra d’un sasso quadrato, & a canto<br />

le sia Saturno, sopra le spalle del<br />

quale posi il libro, ov’ella scrive.<br />

A winged woman, dressed in white,<br />

who looks backward, holding in her<br />

left hand a book upon which she is<br />

shown writing, resting her left foot on<br />

a square stone, and next to whom is<br />

Saturn, on whose back is set her book<br />

where she writes.<br />

THE LESSONS OF ROME ARE COMPLEX, AND VARIED.<br />

Each era has, indeed, found in Rome what they were<br />

searching for (or were prepared to find). If there is a<br />

common underlying approach, however, that explains<br />

how architects operated in Rome within the context of<br />

the classical tradition before the beginning of the<br />

modern era (the later eighteenth century), it could be<br />

characterized as “rhetorical,” shaped in the context of<br />

humanist studies, which saw architecture and the urban<br />

realm as articulate spaces. Therefore, formal studies<br />

make little sense here without reference to the<br />

underlying meaningful ends to which they have been<br />

historically directed, and it can be argued there are<br />

effectively four broad rhetorical themes that informed<br />

the formal choices architects of the past made. In<br />

seeking to articulate the meaning of their projects,<br />

architects drew upon some or all of the following as<br />

sources of inspiration: Site, History, Type, and<br />

Allegory. In fact, all of the great architectural<br />

compositions of Rome are informed by some aspect of<br />

all of these sources; for the purposes of organizing our<br />

walks in Rome, we will rather summarily discuss<br />

exemplary Roman buildings and urban spaces<br />

according to the most overt of the four sources. You are<br />

expected to understand how the other sources may be<br />

integrated factors in these places’ success.<br />

Since we are studying the subject of their<br />

rhetoric by virtue of its formal means, we will analyze<br />

these sites in several ways: planimetric organization,<br />

volume and section, facade composition, and language.<br />

All of these places will reward each of those<br />

investigations; while I will present them on our visits in<br />

the context of those four sources or themes, it will be<br />

your task to engage with the most compelling aspects to<br />

you, and document them for your future use. However,<br />

you must come to understand how each of these aspects depends upon the other, and how the<br />

particulars here are always a consequence of the general. To help you distinguish the four<br />

thematic sources of the rhetoric of Roman classical architecture, please consider the following<br />

brief summary:<br />

SITE: the particular, embedded characteristics or residue—geological, historical, formal,<br />

mythological, poetic, etc.—of a specific place or area; as an example, Lanciani documented<br />

the architectural stratification of Rome in his Forma Urbis Romæ

Site, History, Type, and Allegory:<br />

The Poetics and Rhetoric of the Classical Tradition in Rome<br />

HISTORY: the stories and events that have been associated with a particular patron,<br />

founder, institution, building type, place, etc.<br />

TYPE: those general associations and characteristics of a particular building form allied to<br />

function that transcend specific patrons and places<br />

ALLEGORY: those metaphorical allusions to transcendent meaning that became associated<br />

especially with the mythological and Christian traditions in the Renaissance; please note<br />

that it is the nature of allegory to be multivalent, literate, and somewhat obscure.<br />

Again, it should not be assumed that only one of these themes obtain in the places we will visit<br />

to illustrate them—indeed, it is the particular pleasure of Rome that virtually every place is<br />

complex and layered in its meanings—bur rather that I would like you to consider how these<br />

themes might have furnished the primary intent of the rhetoric of the place. At the same time, I<br />

expect your analyses of these places to investigate the ways in which these themes become<br />

intertwined, noting that, for example, a site’s embedded characteristics include the historical<br />

or mythological, history cannot be divorced from place, etc. What is essential in every case is<br />

that you not see the forms as ends in themselves, but rather rhetorical means toward creating a<br />

more articulate urban and rural environment.<br />

[If] a work of art does not instruct overtly through morals, maxims, or demonstrations<br />

of poetic justice, it should be harmoniously well proportioned, reflecting in its own<br />

order and harmony the harmony God created in the universe. In this way, a work of<br />

art, the microcosmic reflection of the macrocosm, expresses and appeals to the most<br />

rational part of the mind, as well as to the highest emotions, and in its total effect<br />

induces in the whole soul and body that balance, harmony, and proportion the soul<br />

ideally should possess in itself, should impose on and share with the body, and should<br />

take pleasure in perceiving and receiving.<br />

— H. James Jensen, The Muses’ Concord: Literature, Music, and the Visual Arts in the<br />

Baroque Age, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1976, p. 3<br />

CHRONOLOGICAL OVERVIEW<br />

It must be kept in mind that the usual intent of High Renaissance architects was not to<br />

copy specific Roman buildings but to arrive at their own general canons based on a<br />

composite of Roman examples, canons which were generally [only with regards to the<br />

orders] more rigid than those of Vitruvius himself, and much more rigid than those<br />

illustrated by actual Roman buildings. Since French academic architects tended to adhere<br />

to the principles laid down in the writings of these Renaissance authorities even more<br />

closely than did most Italian architects themselves, the French academic canons of<br />

“classic” design in turn tended to become even more rigidly fixed than those of<br />

Renaissance Italy.<br />

—Donald Drew Egbert, The Beaux-Arts Tradition in French Architecture, Princeton,<br />

1980, p. 106<br />

The broad current of Renaissance architecture in Italy, which started to flow slowly in early<br />

quattrocento Florence and disappeared after a brilliant coda in Piedmont midway through the<br />

eighteenth century, was always anchored on the Idea and experience of Rome. Indeed, what<br />

was produced in Rome from its heyday during the Empire through the eighteenth century<br />

arguably has had more of an impact on the trajectory of Western architectural traditions than<br />

any place on earth. As you are here to specifically study the “classical” tradition, and as the<br />

merits of that tradition as it is manifested in Rome are that it is decidedly whole, integrated,<br />

and meaningful, we cannot simply focus on issues of classical “language” without<br />

understanding context (physical, intellectual, cultural), nor can we study “composition” if we<br />

do not know the rhetorical ends to which these compositions were directed. Thus, the urban<br />

realm, the history of the city and the Church, the culture of Renaissance humanism, the allied<br />

arts, etc. are all essential sub-components of what is ostensibly a seminar dedicated to grasping<br />

the formal principles of classical architecture as it is manifested here.

Site, History, Type, and Allegory:<br />

The Poetics and Rhetoric of the Classical Tradition in Rome<br />

The Renaissance as it is here defined, spanning roughly 350 years from Brunelleschi to<br />

Vittone, is the ideal point of departure for understanding the whole spectrum of the classical<br />

tradition from antiquity to neo-Classicism, since it offers the greatest variety of approaches to<br />

engaging with the past, and the most thoughtful examples of dealing with that most<br />

challenging problem of classicism, the relationship of column and wall. Moreover, the<br />

Renaissance’s ability to arrive at new forms and types out of the raw material of the past<br />

offers us an important model for developing our own approaches to our inheritance. It was in<br />

part the understanding of all art as rhetorical, and therefore driven by its message, that yielded<br />

the fertile variety of approaches to the classical tradition in Rome.<br />

To grasp the Renaissance’s approach to classicism we must therefore resort to the<br />

somewhat problematic idea of “language.” Now, while no visual media can replicate the<br />

structure and meanings of words, the analogies between language and built form in the<br />

classical tradition are close enough to help us unlock the mind of Renaissance architects.<br />

Indeed, they were not merely satisfied to dispose their work with competent grammar and<br />

syntax, they were aiming at a meaningful architecture that was rhetorical and poetic, i.e. that<br />

could explain, convince, exhort, and metaphorically re-present ideas from beyond architecture<br />

itself. It was precisely the aspiration to raise the visual arts to the intellectual standing of the<br />

liberal arts that directed Renaissance artists to adopt the aims and methods of rhetoricians and<br />

poets.<br />

Arguably, the fundamental formal challenge of working with the classical language lies<br />

not in the refinement of the Orders themselves, but in the complex ways in which columns and<br />

walls interact. From the moment ancient Roman architects adopted the post and lintel system<br />

of the Greeks and wed it to their development of a wall-based architecture, the complexities,<br />

ambiguities, and contradictions of that marriage challenged and inspired architects to resolve<br />

the potential conflicts into an ever richer whole. Palladio’s “fugal system of proportions” (in<br />

Wittkower’s words) and Borromini’s contrapuntal compositions were only possible because of<br />

their embrace of the challenges of composing with pilasters, half-columns, and colossal orders<br />

(and, because they could consider the bounds of the canon of the Orders fairly fixed).<br />

Moreover, the license exhibited by the greatest architects of the classical tradition was almost<br />

exclusively rhetorical in impetus: in classical rhetorical theory, one is allowed—even<br />

expected—to depart from the rules in order to reach for greater expressive effect (within the<br />

bounds of decorum, of course).<br />

In addition to the Orders and their deployment, we will study the broader issues of<br />

classical composition, or what an early twentieth century writer might have called the “Grand<br />

Manner,” from antiquity through the era of the Grand Tour. Since the elements of the<br />

classical language serve to order the world, the ways in which they occupy and shape space are<br />

fundamental to understanding the very raison d’être of the classical language—its ability to be<br />

rhetorical, to speak coherently and eloquently of the issues that have occupied the concerns of<br />

thoughtful people and societies for millennia.<br />

In so far as a tradition in architecture can be called classical, it must rest on two<br />

analogies: of the building as a body, and of the design as a re-enactment of some<br />

primitive—or if you would rather—of some archetypal action to which our procedure<br />

might refer. From Vitruvius to Boullée, the texts suggest something of the kind, always<br />

in different contexts, since such ideas do not contain, or even imply, the repertory of<br />

norms and procedures which the constant alteration of circumstances forces you to<br />

renew, to rethink and to alter….<br />

—Joseph Rykwert, “The Ecole des Beaux-Arts and the Classical Tradition,” The<br />

Beaux-Arts and Nineteenth Century French Architecture, ed. Robin Middleton, MIT<br />

Press, 1982, p. 17<br />

In concert with our approach of examining the driving themes of Roman classical<br />

architecture, it must also be noted that, at the levels of morphology (form), typology (kind),<br />

and rhetoric (language) there have been, over time, diverse approaches to the inheritance from<br />

the past. One could talk about continuity, inversion, and invention as strategies for dealing<br />

with the legacy of past achievements. When you examine and analyze the places you see this

Site, History, Type, and Allegory:<br />

The Poetics and Rhetoric of the Classical Tradition in Rome<br />

semester, you should reference and seek to document the following very schematic list of how<br />

those strategies might have played out:<br />

CONTINUITY<br />

Morphologies and Typologies:<br />

Insula and Palazzo<br />

Basilica and Church<br />

Temple and Chapel/altar<br />

Triumphal Arch<br />

Villa<br />

Roman Forum and Piazza<br />

City gates<br />

Bridges<br />

Rhetoric:<br />

Orders as genera or types<br />

Disposition of the Orders: Engaged orders, stacked orders<br />

INVERSION<br />

Morphologies and Typologies:<br />

Theater, Colosseum<br />

Temple and Church; Pan-theon vs. Domus Dei<br />

Bath and Church<br />

Imperial Forum and Piazza<br />

Stadium and Piazza<br />

Obelisks<br />

Rhetoric:<br />

meaning of Doric (see Onians)<br />

meaning of the Composite Order<br />

Temple/Church:Inside/Outside (rich/simple)<br />

Rustication<br />

INNOVATION<br />

Morphologies and Typologies:<br />

Palazzo (combining insula and domus elements)<br />

Figural Piazza<br />

Centrally planned church<br />

Nested typologies: e.g. triumphal arch/temple pediment in church facades<br />

Rhetoric:<br />

Orders as a system<br />

Colossal Order; Major/Minor order<br />

Michelangelo’s Ionic<br />

Broken entablatures and pediments; stacked orders and vertical continuity<br />

Illusionistic painting<br />

Bel composto<br />

Fountains<br />

Stairs

Site, History, Type, and Allegory:<br />

The Poetics and Rhetoric of the Classical Tradition in Rome<br />

YOUR TASKS<br />

There is first the archaeological impulse downward into the earth, into the past, the<br />

unknown and recondite, and then the upward impulse to bring forth a corpse whole<br />

and newly restored, re-illuminated, made harmonious and quick.<br />

—Thomas H. Greene, “Resurrecting Rome: The Double Task of the Humanist<br />

Imagination,” Rome in the Renaissance: The City and the Myth, Binghampton, NY:<br />

Center for Medieval and Early Renaissance Studies, p. 41<br />

Your overarching task will be to actively engage with these themes and begin to make the city<br />

of Rome your own, by documenting and analyzing some key sites. To begin, one must come to<br />

terms with the way in which Rome continually built upon itself, not ignoring but<br />

incorporating the past in new construction (the “past” here is understood as everything from<br />

physical spolie to abstract classical ideals). This consciousness of the past can help unlock the<br />

ways in which the builders of this compelling landscape understood what they were doing, but<br />

more importantly can also give you a credible approach to your own interventions in the city.<br />

To operate in any urban context, but especially in Rome, you must know the<br />

ground—physical, cultural, historical—upon which you are building.<br />

To engage with this project you will have to do thorough research, the resources for<br />

which will often need to be found outside our library (the faculty and staff can begin to point<br />

you in the right directions) and in the city itself. You are strongly encouraged to take<br />

advantage of the library card for the American Academy in Rome’s Biblioteca that the School<br />

will endeavor to help you secure (please note that you are ultimately responsible for getting it).<br />

The course will be organized around walks in the city (weather permitting),<br />

occasionally preceded by an introductory presentation in class; we will generally include time<br />

for you to draw (whether documentarily or analytically) on site, and you will be expected to<br />

make similar drawings outside of class. These exercises will be done in notebooks that will be<br />

reviewed periodically over the course of the semester. My expectation is that our semester will<br />

be a long conversation about what we are seeing, which entails each of your contribution in<br />

every class and field trip; your vocal participation, or lack thereof, will affect your final grade.<br />

You will, finally, present the results of a major semester-long assignment to the School. More<br />

specifically about each of these tasks:<br />

1. preparation for each class and field trip<br />

read ahead<br />

research/visit site<br />

prepare to discuss the principles in evidence<br />

2. sketchbooks/journals (must be approximately A4 format, vertical preferred), to be<br />

reviewed periodically over the course of the semester and at the end;<br />

notebooks must include: analytical drawings (graphics and notes), documentary<br />

drawings and reconstructions, lecture notes, and supplemental historical information<br />

(written, redrawn or pasted in)<br />

NB: the primary purpose of the sketchbooks for this class is to develop your skills in<br />

analytical drawing; these will be given the most weight in grading<br />

3. semester project:<br />

Architects in Rome have built upon the four themes—site, history, type, allegory—that<br />

will structure our site visits, and it is expected that you will form over the course of the<br />

semester the ability to analyze and document that process in other sites that we will<br />

not visit. To do this project you will need to do significant research in our library and<br />

elsewhere, not to mention on site, in order to unlock the ideas, intentions and<br />

references of the building you choose to focus on.<br />

Choose a significant structure or space in Rome ( only one student per subject, please)<br />

and present an analytique that documents its sources, references, and any unbuilt<br />

projects in ways that explain the intention of its author(s). You must choose a subject<br />

for study by the fourth class of the semester; be prepared at that time to explain why<br />

you choose a particular place. Preferred subjects include (you may propose others but

Site, History, Type, and Allegory:<br />

The Poetics and Rhetoric of the Classical Tradition in Rome<br />

you must explain why in writing, and they are subject to my approval by the end of the<br />

second week):<br />

1. Porta Santo Spirito and/or the Zecca (Banco di S. Spirito)<br />

2. Porta Pia<br />

3. Acqua Paola<br />

4. Ponte Sant’ Angelo<br />

5. Palazzo Massimo alle Colonne<br />

6. Palazzo and Piazza Montecitorio<br />

7. Villa Lante (Janiculum)<br />

8. Villa Medici<br />

9. Orti Farnesiani<br />

10. Accademia degli Arcadi<br />

11. S. Ivo and the Sapienza<br />

12. S. Maria dell’ Orazione e Morte<br />

13. S. Maria Maggiore<br />

14. S. Maria degli Angeli<br />

15. Ospedale di Santo Spirito<br />

16. Ospizio di S. Trinità dei Pellegrini<br />

The final project will be due in Week 10 (see schedule, following).<br />

There will be assigned readings each week, which will be on reserve either in the form of<br />

photocopies or books; these are meant to supplement the talks we will do on site. Some of<br />

those books which you should be referencing this semester include:<br />

Joseph Connors and John Wilton-Ely, Piranesi Architetto<br />

Amato P. Frutaz, Le Piante di Roma<br />

Krautheimer, Frankl, Corbett, Corpus Basilicarum<br />

Marcia Hall, ed., Rome<br />

Richard Krautheimer, Rome: Profile of a City<br />

The Rome of Alexander VII<br />

Rodolfo Lanciani, Forma Urbis Romæ<br />

Paul Letarouilly, Edifices de Rome Moderne<br />

William L. MacDonald, The Architecture of the Roman Empire I and II<br />

David Mayernik, Timeless Cities<br />

John Onians, Bearers of Meaning<br />

Loren Partridge, The Art of the Renaissance in Rome 1400—1600<br />

Paolo Portoghesi, Roma del Rinascimento<br />

Roma Barocca<br />

John Stamper, The Architecture of Roman Temples<br />

Mark Wilson-Jones, Principles of Roman Architecture<br />

Rudolph Wittkower, Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism<br />

Art & Architecture in Italy, 1600-1750<br />

Sources of Readings by Week (subject to change):<br />

General: David Mayernik, Timeless Cities (esp. pp. 53–58 for the first class)<br />

1. Charles Stinger, The Renaissance in Rome, pp. 254–264 before the first class;<br />

264–282 for second class<br />

2. Joseph Connors, “Alliance and Enmity in Roman Baroque Urbanism,” Römisches<br />

Jahrbuch der Bibliotecha Hertziana [parts 1 and 2]<br />

3. idem [parts 3 and 4]<br />

4. John Onians, “Serlio’s Venice,” Bearers of Meaning<br />

5. David Coffin, The Villa in the Life of Renaissance Rome, Farnesina and Madama<br />

6. John Onians, “Bramante,” Bearers of Meaning<br />

7. Joseph Connors “Virtuoso Architecture in Cassiano’s Rome,” Cassiano Dal<br />

Pozzo’s Paper Museum<br />

8. Rudolph Wittkower, “Bernini,” Art & Architecture in Italy 1600—1750

Site, History, Type, and Allegory:<br />

The Poetics and Rhetoric of the Classical Tradition in Rome<br />

ANALYSIS: WHAT IS IT<br />

analysis noun (pl. -ses): detailed examination of the elements or structure of something,<br />

typically as a basis for discussion or interpretation<br />

• the process of separating something into its constituent elements. Often contrasted<br />

with synthesis .<br />

ORIGIN late 16th cent.: via medieval Latin from Greek analusis, from analuein<br />

‘unloose,’ from ana- ‘up’ + luein ‘loosen.’<br />

—OED<br />

There seems to be a general confusion at our School about what is expected in an analysis<br />

exercise. Like any “creative” act (and analysis is, perforce, “creative” or inventive), it cannot<br />

be precisely codified. At the same time, some of its essential approaches and techniques can be<br />

spelled out, which will follow. But, a priori, my overall expectation is that you will pursue<br />

analysis with a creative, investigative mind, under one guiding rule: you are trying to puzzle<br />

out what is going on that was intended, or at least comprehended, by those who made<br />

whatever it is you are analyzing (it is therefore “objective,” directed toward the object and not<br />

the subject—i.e. you and what you “feel” about it). To be rigorous and rational, analysis<br />

cannot be as subjective as a Rorschach test; it demands, therefore, an understanding of the<br />

context within which the forms were created, or the why of them.<br />

It can be argued that all of the places we will explore this semester attempt to be<br />

synthetic environments, i.e. they strove in one way or another to not be recognized as<br />

composed of discrete pieces. At the same time, each manifests a clear (albeit sometimes<br />

contradictory within the group) attitude toward the disposition and expression of the parts of<br />

which they are composed (from programmatic to architectonic elements). Therefore, to be<br />

credible here your analyses must both pull apart and show how these buildings synthesized<br />

their components.<br />

Some Tactics<br />

Comparison and contrast: look at similar types that take on different forms, or similar<br />

forms for different types<br />

Graphic juxtaposition: to what extent is the same story being told in plan, section and<br />

elevation<br />

Compositional structure: document sequence, rhythm, hierarchies, positive ambiguities<br />

(or multiple readings)<br />

Some Techniques (remember, analysis is graphically reductive by nature)<br />

figure/ground (Nolli), primary/secondary/tertiary, axial/symmetry lines, sequential<br />

overlay, exploded axons, axons generally, juxtaposing two different kinds of graphic<br />

info (e.g. plan and vignette), keyed/”scanned” 1 dwgs. (e.g. ABCBA), etc., etc.<br />

Some Approaches<br />

Process (Design in reverse): try to work out what was intended by the maker(s), or<br />

how they got to the final product (e.g. by assembly, synthesis, transformation, etc.);<br />

not all buildings or places are composed in an additive process (i.e. “buildings made of<br />

other buildings”), but they often do have discrete components (functional or<br />

otherwise); it is a fact in Rome that most of the best architects tried to synthesize, not<br />

distinguish, the diverse parts of which their compositions were made (think of the parts<br />

of the body to the whole)<br />

Relationships: document physical/spatial relationships like bay rhythms, bilateral or<br />

local symmetry, alignments/axes, etc.; remember, in the urban realm these relationships<br />

are as much between buildings as proper to any one building<br />

References: try to work out the sources for the ideas the buildings or spaces depend<br />

upon (typologies, precedents/models from near and far, etc.)<br />

1 scansion noun: the action of scanning a line of verse to determine its rhythm.<br />

• the rhythm of a line of verse.<br />

ORIGIN mid 17th cent.: from Latin scansio(n-), from scandere ‘to climb’ ;

Site, History, Type, and Allegory:<br />

The Poetics and Rhetoric of the Classical Tradition in Rome<br />

FIELD TRIP SKETCHBOOK ASSIGNMENTS<br />

You are of course welcome to explore anything that interests you in your sketchbooks on our<br />

field trips, but the following list is meant to provide an investigative datum upon which you<br />

can build. I will therefore evaluate your sketchbooks first on the basis of the topics that<br />

follow, then on the ones of your choosing.<br />

Field Trip Analysis Topics:<br />

Scenography in Bologna<br />

Sanmichele’s Decorum and Syntax in Verona (City Gates and Palazzi)<br />

Palladio’s Urban Approach in Vicenza<br />

Palladio’s Churches: Theories of Composition<br />

Sansovino’s Rhetoric in the Piazzetta di San Marco<br />

The Palazzo and Its Transformations in Florence: Ruccelai, Strozzi, Medici, Giugni,<br />

Nonfinito, etc.<br />

The Piazza and Its Transformations in Florence: Ss. Annunziata, Sta. Croce, Uffizi<br />

Sacred and Secular Public Space (inside and out) in Siena<br />

SEMESTER GRADES<br />

Class participation (preparation, discussion) 20%<br />

Notebooks (investigation, curiosity, thoroughness) 30%<br />

Project 50%<br />

quality of drawing 15%<br />

quality of information 35%<br />

NAAB CRITERIA<br />

1. ability: Speaking and Writing Skills<br />

2. Ability: Critical Thinking Skills<br />

3. Ability: Graphic Skills<br />

4. Ability: Research Skills<br />

5. Understanding: Formal Ordering Systems<br />

6. ability: Fundamental Design Skills<br />

8. Understanding: Western Traditions<br />

10. Understanding: National and Regional Traditions<br />

11. Ability: Use of Precedents<br />

15. understanding: Sustainable Design<br />

17. ability: Site Conditions<br />

27. understanding: Client Role in Architecture

Site, History, Type, and Allegory:<br />

The Poetics and Rhetoric of the Classical Tradition in Rome<br />

Notes on attendance and out of class visits: since each class will involve a substantial amount<br />

of walking, we need to begin on time; some classes may not begin at via Monterone but<br />

instead at one of our sites; therefore, it is incumbent on you to confirm where the next class<br />

will meet before we end the previous class; late arrivals will count as absences, and after three<br />

unexcused absences you will be subject to a failing grade for the semester. Out of class visits<br />

are required both for your notebooks and for research toward your final project.<br />

ORGANIZATION OF SITE VISITS IN AND OUT OF CLASS BY THEMES:<br />

SITE<br />

in class<br />

out of class<br />

I. Campidoglio Pza. Navona (Pal. Pamphilj), S.<br />

Maria della Pace, S. Ignazio<br />

Roman Forum<br />

Theater of Marcellus<br />

II. Pza. dei Cavalieri di Malta San Clemente, Lateran<br />

III. Cavalieri di Rodi, Palazzo Scalinata di Spagna, Fontana di Palatine<br />

Venezia<br />

Trevi<br />

HISTORY<br />

in class<br />

out of class<br />

I. Imperial Fora, Markets<br />

(Museum)<br />

S. Peter’s Domus Aurea and/or<br />

Colosseum<br />

II. Roman Oratory, Casa<br />

Professa<br />

Collegio Romano,<br />

Propaganda Fide<br />

III. Gesù, S. Andrea della Valle S. Maria in Campitelli, Pal. Baths of Diocletian<br />

Mattei<br />

TYPE<br />

in class<br />

out of class<br />

I. Palazzo Farnese, Spada Palazzo Baldassini, di Firenze,<br />

Borghese<br />

Palazzo Muti-Bussi,<br />

D’Aste<br />

II. Cloister of S. Maria della<br />

Pace, Cancelleria<br />

Sapienza, S. Maria in<br />

Campo Marzio<br />

III. Pantheon and S. Ivo<br />

Tempietto; S. Eligio degli<br />

Orefici<br />

S. Teodoro, S. Agnese,<br />

others<br />

ALLEGORY<br />

in class<br />

out of class<br />

I. Villa Farnesina, Pal. Corsini Villa Madama Villa Giulia and/or<br />

Palazzo Barberini<br />

II. S. Andrea al Quirinale and<br />

S. Carlino, S. Susanna, S.<br />

Maria della Vittoria<br />

Chigi Chapel, S. Maria and<br />

Piazza del Popolo<br />

S. Giacomo degli<br />

Incurabili<br />

SCHEDULE OF IN-CLASS SITE VISITS BY WEEK:<br />

15/17 Sept. 1. SITE I. Campidoglio; Pza. Navona (Palazzo Pamphilj), S. Maria della Pace,<br />

Pza. S. Ignazio<br />

22/24 Sept. 2. HISTORY I. Imperial Fora, Trajan’s Markets (Museum); St. Peter’s<br />

29 Sep./1 Oct. 3. TYPE I. Palazzo Farnese, Spada; Palazzos Baldassini, di Firenze, Borghese<br />

6/8 Oct. 4. ALLEGORY I.A Villa Farnesina, Pal. Corsini SITE II. Pza. dei Cavalieri di<br />

Malta<br />

27/29 Oct. 5. ALLEGORY I.B Villa Madama HISTORY II. Roman Oratory; Casa Professa<br />

3 Nov. 6. TYPE II. Cloister of S. Maria della Pace, Cancelleria<br />

10/12 Nov. 7. SITE III. Cavalieri di Rodi, Palazzo Venezia; Scalinata di Spagna, Fontana<br />

di Trevi<br />

17/19 Nov. 8. HISTORY III. Gesù, S. Andrea della Valle; S. Maria in Campitelli, Pal.<br />

Mattei<br />

24 Nov. 9. TYPE III. Pantheon, S. Eligio degli Orefici, Tempietto<br />

1/3 Dec. 10. ALLEGORY II. S. Andrea al Quirinale and S. Carlino, S. Susanna, Porta Pia;<br />

Chigi Chapel. S. Maria and Piazza del Popolo<br />

NB: Final projects are due this week; day and time of presentation t.b.d.