the explorers journal - The Explorers Club

the explorers journal - The Explorers Club

the explorers journal - The Explorers Club

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

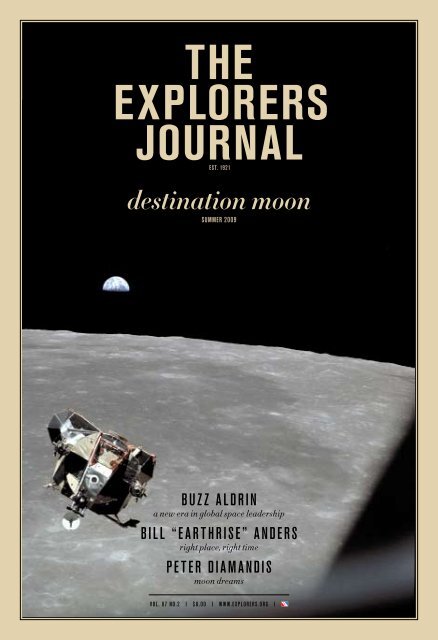

<strong>the</strong><br />

e x p lor e r s<br />

j o u r n a l<br />

EST. 1921<br />

destination moon<br />

summer 2009<br />

buzz aldrin<br />

a new era in global space leadership<br />

Bill “Earthrise” Anders<br />

right place, right time<br />

Peter Diamandis<br />

moon dreams<br />

vol. 87 no.2 I $8.00 I www.<strong>explorers</strong>.org I

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong><br />

summer 2009<br />

destination moon<br />

cover: <strong>the</strong> Apollo 11 lunar module<br />

Eagle returns from <strong>the</strong> surface of <strong>the</strong><br />

moon to dock with <strong>the</strong> command module<br />

Columbia on July 21, 1969. Photograph<br />

by Michael Collins, courtesy NASA.<br />

Static Test Firing of <strong>the</strong> Saturn V S-1C Stage rocket, January 1, 1967. Photograph courtesy NASA.<br />

destination<br />

moon<br />

features<br />

specials<br />

regulars<br />

A new age in global space leadership<br />

by Buzz Aldrin, p. 20<br />

Moon Dreams<br />

by Peter H. Diamandis, illustrations by Andrew Collis, p. 25<br />

Digging <strong>the</strong> Moon<br />

by P. J. Capelotti, p. 28<br />

Right Place, Right time<br />

Jim Clash catches up with Bill “Earthrise” Anders, p. 30<br />

Legacy of Earthrise<br />

images courtesy NASA’s Earth Observatory, p. 32<br />

a century after shackleton<br />

interview by Nick Smith, p. 14<br />

Hidden Caves of Rapa Nui<br />

text and photographs by Marcin Jamkowski, p. 42<br />

Slowly Down <strong>the</strong> Amazon<br />

Nick Smith in conversation with John Hemming, p. 48<br />

president’s letter, p. 2<br />

editor’s note, p. 4<br />

exploration news, p. 8<br />

extreme Medicine, p. 54<br />

extreme cuisine, p. 56<br />

reviews, p. 58<br />

what were <strong>the</strong>y thinking, p. 64

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong><br />

summer 2009<br />

president’s letter<br />

our place in <strong>the</strong> universe<br />

Where once <strong>the</strong> inhabitants of Earth enjoyed <strong>the</strong> luxury of believing<br />

that <strong>the</strong> planet <strong>the</strong>y occupied held a central location in <strong>the</strong><br />

universe, around which all else orbited, evidence ga<strong>the</strong>red over<br />

time eventually tipped <strong>the</strong> scale and humankind succumbed to<br />

<strong>the</strong> realization that our Earth was just one of a number of planets<br />

circling <strong>the</strong> sun. Despite <strong>the</strong> dramatic philosophical modifications<br />

that were required for us to shift away from <strong>the</strong> concept of<br />

a geocentric Earth, <strong>the</strong> importance of our planet and its position<br />

did not dim in our minds but ra<strong>the</strong>r retained much of its lustre<br />

as a featured player in our solar system as we have continued to<br />

accord it a premier role within <strong>the</strong> universe.<br />

Today, we are required once more to reconsider and revamp<br />

our self-deigned positioning as exploration and technology have<br />

been able to far transcend <strong>the</strong> reaches of our own solar system,<br />

indicating that <strong>the</strong> universe is crowded with planets orbiting<br />

<strong>the</strong> distant stars we see in <strong>the</strong> night sky. Since <strong>the</strong> first planet<br />

beyond our solar system was detected in 1995, more than 300<br />

“exoplanets” have been observed—and a far greater number<br />

have yet to be discovered—demonstrating conclusively that<br />

<strong>the</strong> structure of our solar system is not exclusive and indicating<br />

possibly that <strong>the</strong> developments and procedures that led to <strong>the</strong><br />

formation of our planetary system are not especially inimitable.<br />

With each new planetary recording, it has become increasingly<br />

clear that not only are we not at <strong>the</strong> center of <strong>the</strong> universe, we<br />

are merely a solar satellite of a type found orbiting a myriad of<br />

stars.<br />

We are on <strong>the</strong> verge of a new reality, on yet ano<strong>the</strong>r reassessment<br />

of how <strong>the</strong> Earth fits within <strong>the</strong> greater universe. Our<br />

quest to understand our place in <strong>the</strong> universe will be <strong>the</strong> subject<br />

of our 2010 <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong> Annual Dinner on March 20, “<strong>The</strong><br />

Balancing Edge of Infinity: Exploring <strong>the</strong> Universes Out <strong>The</strong>re.”<br />

I hope to see you <strong>the</strong>re.<br />

Lorie Karnath

SAVE<br />

T H E<br />

DATE<br />

Thursday, October 15, 2009<br />

Cipriani Wall Street, New York City<br />

THE PRESIDENT, DIRECTORS AND<br />

OFFICERS OF THE EXPLORERS<br />

CLUB & ROLEX WATCH U.S.A.<br />

Request <strong>the</strong> honor of your company at <strong>the</strong> 2009<br />

Ll Toa Ards Dne<br />

On <strong>the</strong> Brink of Uncertainty, Exploring Risk:<br />

A Survival Guide from <strong>the</strong> Field<br />

Photo: David Jordan www.lavajunkie.com<br />

2009 Lowell Thomas Award Recipients<br />

Bob Barth, CWO, USN (ret), FN’96<br />

Yvon Chouinard, MN’09<br />

Kenneth M. Kamler, M.D., FR’84<br />

Arthur D. Mortvedt, MN’84<br />

James M. Williams, FN’93<br />

Richard B. Wilson, MN’92<br />

Master of Ceremonies: Miles O’Brien<br />

Guest speakers include<br />

Dennis N.T. Perkins, MBA, Ph.D, author of<br />

Leading at <strong>the</strong> Edge, Leadership Lessons from Shackleton’s Antarctic Expedition<br />

Also featuring <strong>The</strong> Calder Quartet and Andrew WK<br />

performing a special composition for <strong>The</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong><br />

by Christine Southworth.<br />

Should you risk not attending Avoid this and reserve early. Tickets go on sale June 1, 2009. Seating for <strong>the</strong> dinner is on a first-come, first served basis. Seating<br />

requests require advance payment. For reservations, please visit www.<strong>explorers</strong>.org or contact <strong>The</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong>: 212-628-8383 or events@<strong>explorers</strong>.org

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong><br />

summer 2009<br />

editor’s note<br />

A giant leap indeed<br />

In his 1951 work, <strong>The</strong> Exploration of Space, Arthur C.<br />

Clarke outlined <strong>the</strong> extraordinary challenge of building<br />

a rocket capable of reaching <strong>the</strong> 25,000-mile-per-hour<br />

velocity necessary to simply escape Earth’s gravitational<br />

pull, much less carry a payload and enough<br />

fuel for a return voyage. He stated that, “When one<br />

allows for this, <strong>the</strong> initial weight of a chemically fuelled<br />

spaceship on taking off from <strong>the</strong> Earth would be not<br />

hundreds but hundreds of thousands of tons—and <strong>the</strong><br />

whole project becomes, if not impossible, certainly<br />

fantastic.”<br />

Fantastic indeed, but possible, thanks to <strong>the</strong><br />

pioneering efforts of visionary rocketeers such as<br />

Wernher von Braun, whose Saturn V rocket propelled<br />

us to <strong>the</strong> Moon. In describing <strong>the</strong> launch of Apollo<br />

11, Buzz Aldrin told <strong>The</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> Journal, “Gulping 15<br />

tons of fuel a second, cooled by water cascading at<br />

50,000 gallons a minute, <strong>the</strong> Saturn V rocket rose with<br />

<strong>the</strong> force of 100,000 locomotives, burning 5,000,000<br />

pounds of fuel in <strong>the</strong> first 150 seconds, getting a full<br />

five inches to <strong>the</strong> gallon.”<br />

On July 20, it will be 40 years since Neil Armstrong<br />

and Buzz Aldrin first stepped foot on <strong>the</strong> Moon. This<br />

issue, in celebration of that momentous event, we have<br />

brought toge<strong>the</strong>r a number of luminaries and new comers<br />

in <strong>the</strong> field of lunar exploration to share with us <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

thoughts not only on where we have been but where<br />

we are going in <strong>the</strong> realm of space exploration.<br />

So, leave your cares below, pull <strong>the</strong> switch, let’s go—<br />

Destination Moon!<br />

A pioneer of America’s space program, Wernher von Braun<br />

stands by <strong>the</strong> five F-1 engines of <strong>the</strong> Saturn V launch<br />

vehicle, Designed and developed by Rocketdyne under <strong>the</strong><br />

direction of <strong>the</strong> Marshall Space Flight Center. Each of<br />

<strong>the</strong> F-1 engines burned 15 tons of liquid oxygen and kerosene<br />

per second to produce 7,500,000 pounds of thrust.<br />

When assembled, <strong>the</strong> Apollo Saturn V, soared to a height<br />

of 111 meters (363 feet), and fully fuelled, weighed 6.5<br />

million pounds. image courtesy NASA.<br />

Angela M.H. Schuster, Editor-in-Chief

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong><br />

Summer 2009<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> club<br />

President<br />

Lorie M.L. Karnath, MBA, hon. Ph.D.<br />

Board Of Directors<br />

Officers<br />

PATRONS & SPONSORS<br />

Honorary President<br />

Don Walsh, Ph.D.<br />

Honor a ry Direc tors<br />

Robert D. Ballard, Ph.D.<br />

George F. Bass, Ph.D<br />

Eugenie Clark, Ph.D.<br />

Sylvia A. Earle, Ph.D.<br />

James M. Fowler<br />

Col. John H. Glenn Jr., USMC (Ret.)<br />

Gilbert M. Grosvenor<br />

Donald C. Johanson, Ph.D.<br />

Richard E. Leakey, D.Sc.<br />

Roland R. Puton<br />

Johan Reinhard, Ph.D.<br />

George B. Schaller, Ph.D.<br />

Don Walsh, Ph.D.<br />

CLASS OF 2010<br />

Anne L. Doubilet<br />

William S. Harte<br />

Mark S. Kassner, CPA<br />

Daniel A. Kobal, Ph.D.<br />

R. Scott Winters, Ph.D.<br />

CLASS OF 2011<br />

Capt. Norman L. Baker<br />

Jonathan M. Conrad<br />

Constance Difede<br />

Kristin Larson, Esq.<br />

Margaret D. Lowman, Ph.D.<br />

CLASS OF 2012<br />

Josh Bernstein<br />

Lt.(N) Joseph G. Frey, C.D.<br />

Gary “Doc” Hermalyn, Ed.D.<br />

Lorie M.L. Karnath, MBA, hon. Ph.D.<br />

William F. Vartorella, Ph.D., C.B.C.<br />

Vice President, Chapters<br />

Lt.(N) Joseph G. Frey, C.D.<br />

Vice President, Membership<br />

Daniel A. Kobal, Ph.D.<br />

Vice President, Operations<br />

Garrett R. Bowden<br />

Vice President, Research & Education<br />

Margaret D. Lowman, Ph.D.<br />

Treasurer<br />

Mark S. Kassner, CPA<br />

Assistant Treasurer<br />

William S. Harte<br />

Secretary<br />

Robert M.T. Jutson, Jr.<br />

Assistant Secretary<br />

Kristin Larson, Esq.<br />

Patrons Of Exploration<br />

Robert H. Rose<br />

Mr. & Mrs. Donald Segur<br />

Michael W. Thoresen<br />

Corporate Partner Of Exploration<br />

Rolex Watch U.S.A., Inc.<br />

Corporate Supporter Of Exploration<br />

National Geographic Society<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong><br />

EDITORS<br />

President & publisher<br />

Lorie M. L. Karnath, MBA, hon. Ph.D.<br />

Editor-in-Chief<br />

Angela M.H. Schuster<br />

Contributing Editors<br />

Jeff Blumenfeld<br />

Jim Clash<br />

Michael J. Manyak, M.D., FACS<br />

Milbry C. Polk<br />

Carl G. Schuster<br />

Nick Smith<br />

Linda Frederick Yaffe<br />

Copy Chief<br />

Valerie Saint-Rossy<br />

ART DEPARTMENT<br />

Art Director<br />

Jesse Alexander<br />

Deus ex Machina<br />

Steve Burnett<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong> © (ISSN 0014-5025) is published<br />

quarterly for $29.95 by THE EXPLORERS CLUB, 46 East 70th<br />

Street, New York, NY 10021. Periodicals postage paid at<br />

New York, NY, and additional mailing offices. Postmaster:<br />

Send address changes to <strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>, 46 East<br />

70th Street, New York, NY 10021.<br />

Subscriptions<br />

One year, $29.95; two years, $54.95; three years, $74.95;<br />

single numbers, $8.00; foreign orders, add $8.00 per year.<br />

Members of THE EXPLORERS CLUB receive <strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong><br />

<strong>journal</strong> as a perquisite of membership. Subscriptions<br />

should be addressed to: Subscription Services, <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>, 46 East 70th Street, New York, NY<br />

10021.<br />

SUBMISSIONS<br />

Manuscripts, books for review, and advertising inquiries<br />

should be sent to <strong>the</strong> Editor, <strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>,<br />

46 East 70th Street, New York, NY 10021, telephone:<br />

212-628-8383, fax: 212-288-4449, e-mail: editor@<br />

<strong>explorers</strong>.org. All manuscripts are subject to review. <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong> is not responsible for unsolicited<br />

materials. <strong>The</strong> views and opinions expressed herein<br />

do not necessarily reflect those of THE EXPLORERS CLUB or<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>.<br />

All paper used to manufacture this magazine comes from<br />

well-managed sources. <strong>The</strong> printing of this magazine is FSC<br />

certified and uses vegetable-based inks.<br />

THE EXPLORERS CLUB, <strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> journaL, THE EXPLORERS<br />

CLUB TRAVELERS, WORLD CENTER FOR EXPLORATION, and <strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong> Flag and Seal are registered trademarks of<br />

THE EXPLORERS CLUB, INC., in <strong>the</strong> United States and elsewhere.<br />

All rights reserved. © <strong>The</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong>, 2009.<br />

50% RECYCLED PAPER<br />

MADE FROM 15%<br />

POST-CONSUMER WASTE

exploration news<br />

edited by Jeff Blumenfeld, expeditionnews.com<br />

8<br />

Polar Centennial<br />

expedition update<br />

commemorating firsts and monitoring climate change<br />

Catlin Arctic Survey<br />

British Polar <strong>explorers</strong> Pen<br />

Hadow, Ann Daniels, and<br />

Martin Hartley were forced to<br />

end <strong>the</strong>ir epic trek across <strong>the</strong><br />

Arctic, 500 kilometers from<br />

<strong>the</strong> North Pole on May 13, on<br />

account of sea ice breakup,<br />

which occurred two to three<br />

weeks earlier than expected.<br />

<strong>The</strong> aim of <strong>the</strong>ir expedition,<br />

which began at Point Barrow,<br />

AK, on February 28 and<br />

which was carried out with<br />

<strong>the</strong> support of <strong>the</strong> University<br />

of Cambridge Department<br />

of Applied Ma<strong>the</strong>matics and<br />

<strong>The</strong>oretical Physics, was to<br />

measure <strong>the</strong> thickness of <strong>the</strong><br />

remaining permanent Arctic<br />

Ocean sea ice.<br />

Peary-Henson<br />

Commemorative Expedition<br />

Lonnie Dupre of Grand Marais,<br />

MN, is no stranger to <strong>the</strong> rigors<br />

of Arctic travel but after 53<br />

days on <strong>the</strong> ice, he was relieved<br />

and happy to reach <strong>the</strong> North<br />

Pole at 9:22 a.m. on April 25.<br />

As leader of <strong>the</strong> Peary-Henson<br />

Commemorative Expedition, he<br />

had ano<strong>the</strong>r burden to carry in<br />

addition to <strong>the</strong> 175 pounds of<br />

food and supplies on <strong>the</strong> sled<br />

he was dragging behind him. “I<br />

didn’t want to let <strong>the</strong> memory of<br />

Robert E. Peary down,” he says.<br />

“I believe Peary and Henson<br />

did make <strong>the</strong> Pole in 1909, and<br />

I didn’t want to do anything less<br />

on this special expedition to<br />

honor <strong>the</strong>ir achievement.”<br />

While Dupre and team were<br />

happy to see <strong>the</strong> North Pole,<br />

some of what <strong>the</strong>y saw on <strong>the</strong><br />

way was deeply disturbing.<br />

Lonnie, who was <strong>the</strong> first man<br />

to reach <strong>the</strong> North Pole during<br />

<strong>the</strong> summer on his “One World”<br />

expedition in 2006, said, “I’ve<br />

never seen such large areas<br />

of recently open water. Not<br />

even in summer. <strong>The</strong> ice on<br />

<strong>the</strong>se leads was very thin. Any<br />

thinner and in many places,<br />

we would not have been able<br />

to cross.” Also, multiyear ice<br />

floes are almost nonexistent.<br />

“<strong>The</strong>re’s only young ice, one to<br />

two years of age. That’s a clear<br />

result of climate change.”<br />

At <strong>the</strong> North Pole, Dupre,<br />

Maxime Chaya, and Stuart<br />

Smith unfurled <strong>the</strong> official flag<br />

of Philadelphia’s Academy of<br />

Natural Sciences, which also<br />

supported one of Peary’s first<br />

expeditions in <strong>the</strong> late 1800s.<br />

Just before reaching <strong>the</strong> Pole,<br />

<strong>the</strong>y lashed toge<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

sleds to use as catamarans<br />

to get across a final stretch<br />

of open frigid water. It was a<br />

race against both time and<br />

<strong>the</strong> “Polar treadmill,” <strong>the</strong><br />

Photograph courtesy BBC

southward-heading ice drift<br />

that snatches away overland<br />

progress as <strong>explorers</strong> approach<br />

<strong>the</strong> North Pole. For<br />

every kilometer <strong>the</strong>y skied,<br />

<strong>the</strong>y lost about a third of it<br />

to <strong>the</strong> treadmill. By <strong>the</strong> time<br />

<strong>the</strong>y reached <strong>the</strong> Pole, <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>explorers</strong> had skied more than<br />

1,000 kilometers, averaging<br />

20 kilometers per day.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Victorinox<br />

North Pole 09 Expedition<br />

John Huston of Chicago, and<br />

Tyler Fish, 34, of Ely, MN, also<br />

reached <strong>the</strong> North Pole on<br />

April 25—becoming <strong>the</strong> first<br />

Americans to make an unsupported<br />

ski trek <strong>the</strong>re—during<br />

<strong>the</strong> Victorinox North Pole 09<br />

Expedition, a brutal 54-day<br />

race across some 700 kilometers.<br />

At nearly a dozen points<br />

<strong>the</strong>y encountered open leads<br />

of water where <strong>the</strong> ice sheet<br />

had fractured and pulled<br />

apart; to traverse <strong>the</strong>se leads<br />

Huston and Fish donned dry<br />

suits and swam across, pulling<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir gear along behind <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

During <strong>the</strong> last four days, <strong>the</strong><br />

duo battled fierce winds, temperatures<br />

of -30ºF to -50ºF,<br />

low visibility, and a sea-ice<br />

drift, which pushed <strong>the</strong>m<br />

back. <strong>The</strong>y had departed from<br />

Ward Hunt Island, <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

tip of Canada’s Ellesmere<br />

Island, on March 2.<br />

Rare Hillary footage<br />

saved from trash<br />

film find in New Zealand<br />

Rare footage of Sir Edmund<br />

Hillary about to embark on<br />

his historic expedition to<br />

Antarctica has been found<br />

EXPLORATION NEWS<br />

in a New Zealand loft among<br />

junk destined for <strong>the</strong> trash. <strong>The</strong><br />

black-and-white 16mm film in<br />

perfect condition was discovered<br />

in February in <strong>the</strong> loft of<br />

CB Norwood, a farm machinery<br />

company in Palmerston<br />

North that supplied tractors for<br />

<strong>the</strong> expedition. It shows Hillary<br />

being teased by team members<br />

for having a haircut and<br />

<strong>the</strong> team leaving Christchurch<br />

aboard <strong>the</strong> ship Endeavour<br />

bound for Antarctica in 1957.<br />

<strong>The</strong> “rusty old can” containing<br />

<strong>the</strong> film was found by a<br />

CB Norwood staff member.<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r staffer, Paul Collins,<br />

took <strong>the</strong> film home to play on<br />

his projector. “It was magic,<br />

absolutely magic,” he told <strong>The</strong><br />

Dominion Post. Hillary led <strong>the</strong><br />

New Zealand component of<br />

<strong>the</strong> joint Commonwealth Trans-<br />

Antarctic Expedition, which<br />

was <strong>the</strong> first party to reach<br />

<strong>the</strong> South Pole since Robert<br />

Falcon Scott’s expedition in<br />

1912. Copies of <strong>the</strong> footage<br />

have been donated to <strong>the</strong> Sir<br />

Edmund Hillary Alpine Centre<br />

at Aoraki/Mt Cook.<br />

IUCN Red list<br />

Irrawaddy<br />

dolphins found<br />

unknown population documented<br />

Some 6,000 Irrawaddy<br />

dolphins have been found<br />

living in freshwater regions<br />

of Bangladesh’s Sundarbans<br />

mangrove forest and adjacent<br />

waters of <strong>the</strong> Bay of<br />

Bengal. Prior to this study,<br />

carried out by scientists from<br />

<strong>the</strong> Wildlife Conservation<br />

Society, <strong>the</strong> largest-known<br />

populations of Irrawaddy dolphins<br />

numbered in <strong>the</strong> low<br />

hundreds. In 2008, <strong>the</strong> species<br />

was listed as vulnerable<br />

in <strong>the</strong> IUCN Red List based<br />

on population declines in<br />

known populations.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Irrawaddy dolphin,<br />

which is related to <strong>the</strong> orca<br />

or killer whale, grows to a<br />

length of 2.5 meters and frequents<br />

large rivers, estuaries,<br />

and freshwater lagoons in<br />

South and Sou<strong>the</strong>ast Asia.<br />

In Myanmar’s Ayeyarwady<br />

River, <strong>the</strong> dolphins are known<br />

for “cooperative fishing” with<br />

humans, where <strong>the</strong> animals<br />

voluntarily herd schools of fish<br />

toward fishing boats. With<br />

<strong>the</strong> aid of dolphins, fishermen<br />

can increase <strong>the</strong> size of<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir catches up to threefold.<br />

<strong>The</strong> dolphins seem to benefit<br />

from this relationship by easily<br />

preying on <strong>the</strong> cornered fish<br />

and those that fall out of <strong>the</strong><br />

fishermen’s nets.<br />

“This discovery gives us<br />

great hope that <strong>the</strong>re is a future<br />

for Irrawaddy dolphins,”<br />

said Brian D. Smith, who<br />

led <strong>the</strong> study. “Bangladesh<br />

clearly serves as an important<br />

sanctuary for Irrawaddy dolphins,<br />

and conservation in this<br />

region should be a top priority.”<br />

Smith and his colleagues<br />

note that <strong>the</strong> dolphins face a<br />

long-term threat of declining<br />

freshwater supplies, caused<br />

by upstream water diversion in<br />

India, coupled with sea-level<br />

rise due to climate change.<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>

EXPLORATION NEWS<br />

Freeze Frame<br />

Project launched<br />

rare polar images online<br />

Deep flight super<br />

falcon unveiled<br />

first production model winged<br />

submersible to be used by NOAA<br />

Engineering wunderkind<br />

Graham Hawkes has just unveiled<br />

his Deep Flight Super<br />

Falcon, <strong>the</strong> first production<br />

model winged submersible<br />

and <strong>the</strong> culmination of some<br />

20 years of design experimentation<br />

in underwater flight<br />

vehicles. Through his pioneering<br />

efforts, Hawkes has made<br />

<strong>the</strong> same transition sub-sea<br />

that <strong>the</strong> Wright Bro<strong>the</strong>rs did<br />

in air, progressing from ballooning<br />

to fixed-wing aircraft.<br />

One of <strong>the</strong> first projects for<br />

Super Falcon is <strong>the</strong> launch<br />

of VIP in <strong>the</strong> Sea, a program<br />

created by Hawkes Ocean<br />

Technologies and NOAA<br />

National Marine Sanctuaries<br />

to enable communicators—<br />

scientists, politicians, policymakers,<br />

educators, and<br />

artists—to experience <strong>the</strong><br />

oceans as never before,<br />

bringing <strong>the</strong>m on flights<br />

beneath <strong>the</strong> sea. <strong>The</strong> program’s<br />

goal is to have VIPs<br />

experience <strong>the</strong> oceans<br />

firsthand, so <strong>the</strong>y can make<br />

that personal connection,<br />

which is critical in promoting<br />

education, exploration, and<br />

preservation of our ocean<br />

planet. <strong>The</strong> first VIP dives<br />

will take place this summer<br />

at <strong>the</strong> Monterey Bay National<br />

Marine Sanctuary.<br />

“We are very excited to<br />

help launch VIP in <strong>the</strong> Sea,”<br />

said William J. Douros, West<br />

Coast Regional Director of<br />

NOAA’s Office of National<br />

Marine Sanctuaries. “It is an<br />

excellent way to showcase<br />

our national marine sanctuaries<br />

and call attention to <strong>the</strong><br />

need to conserve and protect<br />

our ocean territories. Until<br />

now, <strong>the</strong> technology was not<br />

available to take VIPs safely<br />

and comfortably into <strong>the</strong><br />

deeper parts of <strong>the</strong> oceans.<br />

We see Super Falcon as an<br />

ambassador to <strong>the</strong> seas.”<br />

Thousands of rare and fragile<br />

images spanning some<br />

150 years of polar exploration<br />

have been painstakingly<br />

restored for <strong>the</strong> digital age<br />

by Cambridge University’s<br />

Freeze Frame project, which<br />

has made more than 20,000<br />

images from <strong>the</strong> Scott Polar<br />

Research Institute (SPRI)<br />

archive available free to<br />

people around <strong>the</strong> world.<br />

<strong>The</strong> digital archive, which<br />

features <strong>the</strong> expeditions of<br />

Sir John Franklin, Captain<br />

Sir Robert Falcon Scott, Sir<br />

Ernest Shackleton and <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

modern counterparts, provides<br />

fascinating insight into<br />

<strong>the</strong> beauty and privations<br />

of life at <strong>the</strong> poles; from <strong>the</strong><br />

Heroic Age of Exploration<br />

to Sir Ranulph Fiennes’<br />

Transglobe Expedition of<br />

<strong>the</strong> 1980s. Also on <strong>the</strong> site<br />

are extracts from diaries,<br />

expedition reports, letters,<br />

and personal papers<br />

of expedition members.<br />

For more information:<br />

www.freezeframe.ac.uk.<br />

Deep flight super falcon flies over <strong>the</strong> wreck of <strong>the</strong> Rhone, BVI. Photograph by Graham Waters. Shackleton’s Terra Nova, courtesy Freeze Frame Project.<br />

10

EXPLORATION NEWS<br />

Cucudeta zabkai, one of <strong>the</strong> previously undescribed species belonging to a completely new genus. Photograph by Wayne Maddison.<br />

jumping spiders and<br />

a new gecko<br />

Papua New Guinea species finds<br />

A jumping spider and a<br />

striped gecko were among<br />

dozens of new species found<br />

on a Papua New Guinea expedition<br />

to help Barrick Gold<br />

Co. decide how to develop its<br />

mines. Fifty types of spiders,<br />

three frogs, two plants, and<br />

<strong>the</strong> gecko, which were among<br />

<strong>the</strong> species documented on<br />

<strong>the</strong> recent trek, are believed<br />

to be new to science, said<br />

<strong>the</strong> Washington D.C.-based<br />

Conservation International.<br />

Jumping spiders are found<br />

in every part of <strong>the</strong> world except<br />

Antarctica. Capable of<br />

jumping 30 times <strong>the</strong>ir body<br />

length, some of <strong>the</strong> 5,000<br />

documented species are<br />

common in households.<br />

Two of <strong>the</strong> jumping spiders’<br />

eight eyes have evolved to<br />

be large, with high-resolution<br />

vision to spot prey. Female<br />

jumping spiders also use this<br />

heightened visual faculty to<br />

watch males, who show off<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir colorful bodies during<br />

courtship dances.<br />

Some of <strong>the</strong> species discovered<br />

are highly distinctive, occupying<br />

“lonely” branches on<br />

<strong>the</strong> evolutionary tree of jumping<br />

spiders, said Wayne Maddison,<br />

a professor of zoology and botany<br />

at <strong>the</strong> University of British<br />

Columbia, who collected 500<br />

spider specimens.<br />

This cooperative expedition<br />

by Conservation International,<br />

<strong>the</strong> University of British<br />

Columbia, Montclair State<br />

University, and local Papuan<br />

researchers was funded by<br />

Porgera Joint Venture, 95<br />

percent owned by Barrick, <strong>the</strong><br />

world’s largest gold producer.<br />

<strong>The</strong> discoveries will increase<br />

<strong>the</strong> mining industry’s ability to<br />

balance development needs<br />

with protecting <strong>the</strong> wildlife<br />

and forests of <strong>the</strong> people in<br />

Papua New Guinea’s Kaijende<br />

Uplands. New Guinea has<br />

proven a rich hunting ground<br />

for biologists. In 2006,<br />

Conservation International<br />

said it found a “lost world” of<br />

35 previously undocumented<br />

species on <strong>the</strong> Indonesian<br />

half of <strong>the</strong> island.<br />

TKTKT<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>

SPECIAL REPORT<br />

Earth’s oceans<br />

in focus<br />

<strong>explorers</strong> take action<br />

One need only gaze at Earthrise, <strong>the</strong> iconic image<br />

of our planet shot by Apollo 8 astronaut Bill<br />

Anders on Christmas Eve 1968 (see page 30),<br />

to realize that most of Earth’s surface is covered<br />

by water. It is water that sustains us and all o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

living things on <strong>the</strong> planet. Ocean exploration,<br />

although relatively new, has revealed <strong>the</strong> Earth’s<br />

magnificent features at depth, confirming <strong>the</strong> idea<br />

that we inhabit a “blue planet.” Yet it is clear from<br />

a number of important studies in recent years that<br />

humanity has been a poor steward of its most<br />

vital resource. At present, less than 1 percent<br />

of Earth’s oceans are protected from dragging,<br />

drilling, mining, overfishing, or dumping of waste.<br />

As <strong>explorers</strong>, many of us have seen this damage<br />

firsthand and we are alarmed.<br />

Signs of distress include more than 300 dead<br />

zones in coastal waters near dense human populations.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se anoxic (oxygen-depleted) areas are<br />

caused by algal blooms and fed by runoff of sewage<br />

and fertilizers. Lethal jellyfish thrive in anoxic<br />

waters, and <strong>the</strong>ir exploding populations pose an<br />

increasing hazard to beachgoers and fishermen.<br />

12<br />

Adding to this damage is ocean acidification<br />

resulting from carbon emissions, especially CO2,<br />

entering <strong>the</strong> oceans, changing ocean chemistry<br />

and propelling climate change. In acidic waters,<br />

coral reefs and o<strong>the</strong>r calcareous skeletonized species<br />

disintegrate. Half of <strong>the</strong> world’s coral reefs<br />

have disappeared already and scientists predict<br />

that coral may become extinct in 50 years.<br />

To begin addressing <strong>the</strong> challenge of preserving<br />

what is left of Earth’s marine resources, <strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong> convened its first State of <strong>the</strong><br />

Oceans Forum on March 22. Chaired by marine<br />

toxicologist Susan Shaw (FN’07), founder of <strong>the</strong><br />

Marine Environmental Research Institute, and<br />

moderated by renowned oceanographer Sylvia<br />

A. Earle (HON’81), <strong>the</strong> panel included coral reef<br />

scientist, Nancy Knowlton, of <strong>the</strong> Smithsonian<br />

Institution; oceanographer and deep-sea robotics<br />

pioneer, David Gallo (FN’90) of <strong>the</strong> Woods Hole<br />

Oceanographic Institution; David Guggenheim<br />

(FN’08) founder of 1planet1ocean; and wildlife<br />

expert Jim Fowler (HON’66).<br />

“<strong>The</strong> oceans are truly in crisis,” said Shaw in her<br />

Photograph courtesy Charles Moore, Algalita Marine Research Foundation.

opening remarks. It is time for <strong>explorers</strong> to take up<br />

<strong>the</strong> challenge and find solutions. Today is a start.”<br />

Earle—<strong>the</strong> inspiration behind <strong>the</strong> recent launch<br />

of Google Ocean—addressed <strong>the</strong> global problem<br />

of overfishing. “With our new technologies and<br />

predatory nature, we are strip-mining <strong>the</strong> sea—we<br />

have eaten 90 percent of all <strong>the</strong> large fish in <strong>the</strong><br />

sea, and we’re now consuming all <strong>the</strong> medium to<br />

small fish.” In addition to wasteful and barbaric<br />

fishing practices such as shark-finning and excessive<br />

bycatch, megatrawlers and draggers are<br />

bulldozing <strong>the</strong> ocean floor, stripping large areas<br />

of marine life. Scientists predict that without intervention<br />

global fisheries will collapse by 2050.<br />

Shaw described <strong>the</strong> oceans as “sinks and<br />

reservoirs of pollution,” explaining that organic<br />

pollutants flowing from our homes, offices, farms,<br />

lawns, and landfills are entering our coastal waters<br />

and <strong>the</strong> ocean food web. “We have long held<br />

<strong>the</strong> belief that <strong>the</strong> sea was so vast, it could dilute<br />

all <strong>the</strong> poisons from land. This became a doctrine<br />

that enabled states to continue ocean dumping<br />

until <strong>the</strong> early 1990s.” Shaw said, noting that<br />

few realize that many of <strong>the</strong>se pollutants are so<br />

persistent, <strong>the</strong>ir breakdown can be measured in<br />

geologic time. “As top predators, marine mammals<br />

accumulate high levels of man-made, toxic<br />

chemicals in <strong>the</strong>ir bodies.” Since 1980, Shaw has<br />

been documenting die-offs of seals, dolphins, and<br />

whales, which have increased dramatically worldwide<br />

(see THE EXPLORERS JOURNAL, Spring 2008).<br />

“<strong>The</strong>se animals are telling us that something is<br />

very wrong in <strong>the</strong> sea. We are poisoning <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

habitat, <strong>the</strong>ir food, and, ironically, ourselves.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> world produces more than 100 million tons<br />

of plastic each year, some 10 percent of which<br />

ends up in <strong>the</strong> sea. According to <strong>the</strong> United Nations<br />

Environment Programme, <strong>the</strong>re are 18,000 pieces<br />

of plastic per square kilometer of ocean. Much of it<br />

can be found in “garbage gyres”—floating masses<br />

of debris trapped in ocean current vortices. <strong>The</strong><br />

largest of <strong>the</strong>se is <strong>the</strong> Texas-sized North Pacific<br />

Gyre, first documented by Captain Charles<br />

Moore (MN’04) of <strong>the</strong> Algalita Marine Research<br />

Foundation. Plastics kill hundreds of thousands of<br />

marine mammals and millions of seabirds annually.<br />

While most of us are aware of <strong>the</strong> problem of<br />

wildlife entanglement, <strong>the</strong> more silent and perhaps<br />

deadly aspect of plastic trash is <strong>the</strong> chemicals <strong>the</strong>y<br />

deliver to <strong>the</strong> sea as <strong>the</strong>y photodegrade. Not all of<br />

<strong>the</strong> plastic trash floats. According to Greenpeace,<br />

some 70 percent of discarded plastic sinks to <strong>the</strong><br />

bottom of <strong>the</strong> sea, smo<strong>the</strong>ring <strong>the</strong> ocean floor and<br />

killing <strong>the</strong> marine life found <strong>the</strong>re.<br />

“On Earth, we are 7 billion people impacting<br />

an incredibly sensitive system,” said David Gallo,<br />

expressing concern about human damage to our<br />

oceans. He emphasized <strong>the</strong> need for change in<br />

<strong>the</strong> ways we use <strong>the</strong> sea, saying, “We have only<br />

explored a small fraction—a mere 3 percent—of <strong>the</strong><br />

oceans and we’re already overexploiting <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

How we go forward from here will set <strong>the</strong> stage<br />

for centuries to come.”<br />

In addition to highlighting <strong>the</strong> plight of our<br />

oceans through exhaustive statistics, panelists<br />

put forth a number of ideas for marine conservation.<br />

Chief among <strong>the</strong>m are establishing networks<br />

of marine protected areas, reducing <strong>the</strong> use of<br />

toxic chemicals and carbon emissions, promoting<br />

green technologies, and reaching a broader<br />

public with an ocean message.<br />

“Coral reefs, considered <strong>the</strong> rainforests of <strong>the</strong><br />

sea, support an estimated 25 percent of all marine<br />

species,” said Nancy Knowlton, who believes it is<br />

possible to build resilience into coral reef systems.<br />

“We know how to do this. It involves two<br />

things—controlling fishing pressure and improving<br />

water quality. When areas are protected, we see<br />

a big difference. We know protection works. It’s<br />

a matter of political will, not <strong>the</strong> science, not <strong>the</strong><br />

technology. Our biggest challenge,” she added,<br />

“is to develop technology to significantly reduce<br />

CO2 emissions.”<br />

“Much of <strong>the</strong> historic mismanagement of our<br />

marine resources can be blamed on public ignorance<br />

about <strong>the</strong> state of <strong>the</strong> oceans,” said David<br />

Guggenheim, who launched <strong>the</strong> Ocean Doctor<br />

Expedition, taking it to schools across <strong>the</strong> country.<br />

“Kids have a natural affinity for <strong>the</strong> oceans, and<br />

<strong>the</strong>y are worried, <strong>the</strong>y want to help. <strong>The</strong> need for<br />

education has never been greater.”<br />

As an important first step, <strong>the</strong> panelists have<br />

drafted a Call to Action for <strong>explorers</strong>, which can<br />

be found on our website www.<strong>explorers</strong>.org,<br />

while a podcast of <strong>the</strong> forum has been posted<br />

at http://1planet1ocean.org/video-state-of-<strong>the</strong>oceans-forum-a-call-to-action.<br />

Based on <strong>the</strong> extraordinary<br />

response to <strong>the</strong> forum, two follow-up<br />

ocean sessions have been planned. <strong>The</strong> first is<br />

set for Monday, December 7, 2009; ano<strong>the</strong>r will<br />

be held in spring 2010. For information, contact<br />

Susan Shaw: sshaw@meriresearch.org.<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>

a century after<br />

Shackleton<br />

This year marks <strong>the</strong> centenary of <strong>the</strong> British Antarctic<br />

Expedition 1907–1909, better known as Nimrod after <strong>the</strong> ship on<br />

which Ernest Shackleton and his men traveled to <strong>the</strong> White<br />

Continent. <strong>Explorers</strong> Journal Contributing Editor Nick Smith<br />

discussed <strong>the</strong> significance of Sir Ernest’s first major expedition<br />

as leader with his only granddaughter, <strong>the</strong> Honorable<br />

Alexandra Shackleton.<br />

interview by Nick Smith<br />

<strong>The</strong> story of Nimrod, <strong>the</strong> first major expedition<br />

to be led by Sir Ernest Shackleton (HON’1912), is<br />

one of <strong>the</strong> great tales of <strong>the</strong> Heroic Age of Antarctic<br />

Exploration. Admiral Sir Edward Evans—who had<br />

been on Captain Scott’s Discovery expedition of<br />

1902–1904 with Shackleton–described it as “a<br />

good, sound, scientific program.”<br />

“Far<strong>the</strong>st North, Far<strong>the</strong>st South,” Ernest Shackleton, right, with Robert E. Peary at <strong>The</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong> Annual Dinner, March 29, 1912.<br />

14

Shackleton’s compass from <strong>the</strong> nimrod expedition (private collection). Photograph by Nick Smith.<br />

But <strong>the</strong> British Antarctic Expedition 1907–1909,<br />

to name it correctly, has been overshadowed<br />

by o<strong>the</strong>r events in <strong>the</strong> Polar regions, including<br />

<strong>the</strong> failure of Scott’s Terra Nova expedition and<br />

Shackleton’s heroic rescue mission of <strong>the</strong> crew<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Endurance. So well known are <strong>the</strong>se later<br />

expeditions that it is easy to forget <strong>the</strong> real impact<br />

of Nimrod, <strong>the</strong> stout little sealer that departed<br />

London on July 20, 1907. Having been tugged<br />

from New Zealand to <strong>the</strong> limits of <strong>the</strong> Antarctic<br />

ice, <strong>the</strong> vessel, overloaded with coal, had a steaming<br />

radius that would allow its captain to explore<br />

as far as <strong>the</strong> Bay of Whales, before settling on<br />

Cape Royds as <strong>the</strong> expedition’s shore base.<br />

From this historic hut—where Shackleton<br />

wintered in 1908—a party of four men set out on<br />

one of <strong>the</strong> greatest sledge journeys in history.<br />

After passing Scott’s “far<strong>the</strong>st South,” every new<br />

feature became Shackleton’s own discovery. His<br />

expedition attained <strong>the</strong> South Geomagnetic Pole,<br />

made <strong>the</strong> first ascent of <strong>the</strong> highest mountain on<br />

<strong>the</strong> “White Continent,” discovered coal and fossils,<br />

experimented with motorized transport, and<br />

made a heroic attempt on <strong>the</strong> Geographical Pole.<br />

Despite <strong>the</strong> many brushes with death, Nimrod<br />

was, as Evans later wrote, an “eminently successful<br />

expedition.”<br />

On March 4, 1909, Nimrod departed <strong>the</strong><br />

Antarctic ice edge on <strong>the</strong> home leg of <strong>the</strong> British<br />

Antarctic Expedition. And although <strong>the</strong> expedition<br />

had not succeeded in its ultimate goal—<strong>the</strong> attainment<br />

of <strong>the</strong> South Pole—it was arguably <strong>the</strong> most<br />

important and significant excursion to Antarctica<br />

of its time. Every one of Ernest Shackleton’s men<br />

returned to safety.<br />

Nick Smith: How did Nimrod come about<br />

Alexandra Shackleton: Nimrod was Shackleton’s first<br />

expedition as leader. He went South originally with<br />

Captain Scott on <strong>the</strong> Discovery expedition. He was<br />

part of Scott’s sou<strong>the</strong>rn party that got to within a<br />

few hundred miles of <strong>the</strong> Pole. But he regarded<br />

<strong>the</strong> Pole as unfinished business. And so he put<br />

toge<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> Nimrod expedition. <strong>The</strong>re were scientific<br />

objectives as well as those of exploration, but<br />

in fact what he really wanted was <strong>the</strong> Pole.<br />

NS: What do you think Nimrod achieved<br />

AS: Nimrod achieved a lot. <strong>The</strong> first ascent of Mt.<br />

Erebus as well as <strong>the</strong> publication of <strong>the</strong> first book<br />

in <strong>the</strong> Antarctic, Aurora Australis. Lots of valuable<br />

scientific work was undertaken. Coal was discovered<br />

and <strong>the</strong> South Magnetic Pole was reached.<br />

It sounds quite simple to reach <strong>the</strong> Magnetic Pole,<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>

ut in fact it moves about according to <strong>the</strong> angle<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Earth’s magnetic field. After an epic trek of<br />

1,260 miles (2,027 km) unsupported—a record<br />

that stood for 80 years—<strong>the</strong> expedition managed<br />

to achieve that. But it wasn’t all success. <strong>The</strong> first<br />

motorcar was taken and that didn’t work out.<br />

NS: But your grandfa<strong>the</strong>r didn’t get to <strong>the</strong> South<br />

Pole<br />

AS: Ernest Shackleton did not get what he most<br />

wanted from <strong>the</strong> Nimrod expedition. He did not get<br />

to <strong>the</strong> Pole. He got 366 miles (589 km) nearer than<br />

<strong>the</strong> Discovery expedition, but at 97 miles (156 km)<br />

from <strong>the</strong> Pole he took <strong>the</strong> decision to turn back.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y were all in a bad state physically. <strong>The</strong> elevation<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Polar Plateau was affecting<br />

<strong>the</strong>m badly as well as <strong>the</strong><br />

lack of food. He could possibly<br />

have struggled on to <strong>the</strong> Pole, but<br />

he knew it was unlikely that he<br />

would bring his men back alive.<br />

So he decided to turn back: a decision<br />

that has been described<br />

as one of <strong>the</strong> great decisions in<br />

polar history, one of which I am<br />

extremely proud. To turn his back<br />

on glory for <strong>the</strong> sake of life—it really<br />

defined him as a leader and<br />

it defined his priorities. We are<br />

all defined by our priorities. His<br />

priorities were quite simply his<br />

men. Afterwards he said to my<br />

grandmo<strong>the</strong>r: “I thought you’d<br />

ra<strong>the</strong>r have a live donkey than a<br />

dead lion.”<br />

NS: <strong>The</strong> British Antarctic Expedition 1907–1909<br />

is more commonly known after <strong>the</strong> ship Nimrod.<br />

What can you tell me about <strong>the</strong> ship itself<br />

AS: <strong>The</strong> ship was a very small, 40-year-old sealer,<br />

originally called Bjørn. Small and tatty. All my<br />

grandfa<strong>the</strong>r’s ships were secondhand. In fact, <strong>the</strong><br />

only purpose-built polar ship of <strong>the</strong> time was Scott’s<br />

Discovery, which cost Scott as much as <strong>the</strong> entire<br />

Nimrod expedition. Nimrod set sail from London,<br />

but in fact Ernest Shackleton joined <strong>the</strong> ship in New<br />

Zealand. In order to save coal, Nimrod was <strong>the</strong>n<br />

towed—<strong>the</strong> longest tow for a very long time—down<br />

to <strong>the</strong> Antarctic Circle. Nightmare tow, nightmare<br />

wea<strong>the</strong>r. <strong>The</strong> Koonya was <strong>the</strong> tug that carried<br />

out <strong>the</strong> tow and at one stage <strong>the</strong> wea<strong>the</strong>r was so<br />

16<br />

bad <strong>the</strong> ships could only just see <strong>the</strong> tops of each<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r’s masts. It was an incredible feat of seamanship<br />

that <strong>the</strong> line was kept as it should have been.<br />

And Nimrod was quite overloaded with supplies for<br />

winter. My grandfa<strong>the</strong>r said that <strong>the</strong> ship looked like<br />

a reluctant schoolboy being dragged to school.<br />

NS: In <strong>the</strong> context of <strong>the</strong> Heroic Age of Antarctic<br />

Exploration, Nimrod is not <strong>the</strong> best known of expeditions,<br />

but perhaps is one of <strong>the</strong> most important.<br />

Why do you think it has been overshadowed<br />

AS: It’s not Shackleton’s best-known expedition,<br />

but I think it was as important as <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs, quite<br />

honestly. Of course, with <strong>the</strong> Endurance expedition<br />

<strong>the</strong>re was an epic rescue involving an 800-<br />

mile crossing of stormy seas in<br />

<strong>the</strong> 23-foot James Caird, with<br />

<strong>the</strong> men waiting on Elephant<br />

Island and <strong>the</strong> rescue party<br />

climbing <strong>the</strong> unclimbed peaks of<br />

South Georgia.<br />

NS: In 1908, Nimrod returned to<br />

New Zealand and <strong>the</strong>n in 1909<br />

it arrived back in Antarctica to<br />

collect <strong>the</strong> expedition team…<br />

AS: Every single man returned.<br />

That’s why when I recently went<br />

to visit my grandfa<strong>the</strong>r’s Nimrod<br />

expedition base hut at Cape<br />

Royds—beautifully conserved<br />

by <strong>the</strong> New Zealand Antarctic<br />

Heritage Trust—it looked as if<br />

<strong>the</strong>y had just stepped out. It was<br />

an incredible experience. First<br />

you notice <strong>the</strong> smell of wood and<br />

lea<strong>the</strong>r, and <strong>the</strong>n you notice that it’s lit by natural<br />

light. And <strong>the</strong>n you notice <strong>the</strong> hams hanging<br />

up and <strong>the</strong> socks and <strong>the</strong> clo<strong>the</strong>s and <strong>the</strong> Mrs.<br />

Sam stove. I felt a great wave of grief because I’m<br />

looking at <strong>the</strong> past, and <strong>the</strong> past as <strong>the</strong> cliché has<br />

it, won’t come again. But afterwards, after I had<br />

processed <strong>the</strong> experience, I decided that <strong>the</strong> hut<br />

itself is not a sad place because everyone came<br />

back alive.<br />

NS: <strong>The</strong> point of your recent voyage to Antarctica<br />

was to visit your grandfa<strong>the</strong>r’s hut<br />

AS: Yes. A documentary was being made about<br />

me by a New Zealand filmmaker Mary-Jo Tohill to<br />

record <strong>the</strong> visit to my grandfa<strong>the</strong>r’s hut for <strong>the</strong> very<br />

Shackleton’s polar medal with bars, <strong>the</strong> only medal in existence to commemorate three expeditions (private collection). photograph by Nick Smith.

first time in <strong>the</strong> Nimrod year. It’s a long voyage.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Ross Sea is a very long way away. <strong>The</strong> ice<br />

was extremely bad and we couldn’t get to all <strong>the</strong><br />

places we wanted to get to, even in a powerful<br />

icebreaker. But we did get to Cape Royds and it<br />

was an astonishing experience, for which I’m very<br />

grateful. All my life I wanted to visit it.<br />

<strong>the</strong> nimrod. Photograph courtesy Alexandra Shackleton.<br />

NS: What is <strong>the</strong> hut like<br />

AS: It’s about 30 by 15 feet. Fifteen men wintered in<br />

it, and o<strong>the</strong>r expeditions used it, too. It’s a permanent<br />

building in that it’s still <strong>the</strong>re, but it was prefabricated<br />

in England, taken apart, and re-erected<br />

<strong>the</strong>re. <strong>The</strong> packing cases were taken apart and<br />

used for things like furniture, and of course <strong>the</strong><br />

covers of Aurora Australis. Two members of <strong>the</strong><br />

expedition took a short course and <strong>the</strong>y were lent<br />

a small press. But of course it was incredibly difficult<br />

because <strong>the</strong>re was all <strong>the</strong> volcanic dust—<strong>the</strong><br />

scoria—that one walks through because Erebus,<br />

a live volcano, is nearby. And <strong>the</strong> ink would freeze<br />

and you’d drop a plate and you’d have to start all<br />

over again. It was painstaking and a huge achievement<br />

of very high standard. You would not think<br />

that <strong>the</strong>y had not printed before.<br />

NS: Do you think Aurora Australis tells us much<br />

about <strong>the</strong> Nimrod expedition<br />

AS: Aurora Australis is effectively a Nimrod anthology.<br />

<strong>The</strong> subjects range from science to fantasy, from<br />

humor to poetry. Ernest Shackleton contributed two<br />

of his poems. <strong>The</strong> humor has changed a bit—some<br />

of <strong>the</strong> things <strong>the</strong>y thought funny we don’t think quite<br />

so funny today. And of course generously illustrated,<br />

too. We don’t know exactly how many were produced—probably<br />

not more than a hundred. One was<br />

discovered recently in a barn in Northumberland. I<br />

think it was sold for about £56,000 and I think that<br />

was <strong>the</strong> top price. Obviously, condition makes a<br />

difference and whe<strong>the</strong>r Shackleton or any of <strong>the</strong><br />

o<strong>the</strong>rs had signed it. I think Aurora not only throws<br />

light on <strong>the</strong> members of <strong>the</strong> expedition and how <strong>the</strong>y<br />

thought a hundred years ago, but also on <strong>the</strong> leader<br />

who chose <strong>the</strong>se men. <strong>The</strong>y are like this, and he<br />

chose <strong>the</strong>se people.<br />

NS: What do you think is <strong>the</strong> legacy of Nimrod<br />

AS: <strong>The</strong> significance of Nimrod is that it defined<br />

Ernest Shackleton as a leader. <strong>The</strong>re has been a<br />

great upsurge of interest in him over <strong>the</strong> past ten<br />

years for one reason: Leadership.<br />

Nimrod, <strong>The</strong> 1907–1909<br />

British Antarctic Expedition,<br />

in cold, hard facts<br />

Excerpted with permission from A Chronology of<br />

Antarctic Exploration: a Synopsis of Events and Activities<br />

from <strong>the</strong> Earliest Times until <strong>the</strong> International Polar<br />

Years, 2007–09, by Robert Keith Headland<br />

Party of 15 men wintered at Cape Royds<br />

on Ross Island; climbed Mount Erebus<br />

(3794 m), 10 March 1908; Shackleton<br />

and 3 o<strong>the</strong>rs (Jameson Boyd Adams,<br />

Eric Stewart Marshall, and John Robert<br />

Francis [Frank] Wild), discovered and<br />

sledged up <strong>the</strong> Beardmore Glacier to<br />

<strong>the</strong> far<strong>the</strong>st south of 88º 38' S (01º 62'<br />

[180 km] from <strong>the</strong> South Pole) where<br />

Shackleton took possession of <strong>the</strong> Polar<br />

Plateau for King Edward VII, 9 January<br />

1909; insufficient supplies necessitated<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir return; discovered nearly 500 km<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Transantarctic Mountains, flanking<br />

<strong>the</strong> Ross Ice Shelf; discovered coal at<br />

Mt Buckley. Tannatt William Edgeworth<br />

David leading a party of three reached<br />

<strong>the</strong> region of <strong>the</strong> South Magnetic Pole<br />

(72º 42' S, 155º 27' E) and took possession<br />

for Britain of Victoria Land <strong>the</strong>re, 16<br />

January 1909. Dogs and ponies used for<br />

some sledge hauling. Visited Macquarie<br />

Island, searched for “Dougherty’s Island.”<br />

First experiments in motor transport in<br />

Antarctica, an Arrol Johnston motorcar<br />

was used with limited success; ciné<br />

photographs of penguins and seals were<br />

made. <strong>The</strong> expedition used New Zealand<br />

postage stamps specially overprinted<br />

“King Edward VII Land” and an expedition<br />

canceller; Shackleton was appointed<br />

Post-Master. Book Aurora Australis,<br />

printed at Cape Royds, 90 copies made.<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>

destination<br />

moon<br />

“Here men from <strong>the</strong> planet Earth first set foot on<br />

<strong>the</strong> Moon. July 1969 a.d. We came in peace for all<br />

mankind.”<br />

On July 20, it will be 40 years since Neil<br />

Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin first stepped on <strong>the</strong><br />

Moon in one giant leap for humankind. Between<br />

July 1969 and December 1972, 12 astronauts<br />

spent 160 hours on <strong>the</strong> Moon, traveling 100<br />

kilometers across its surface both on foot and in<br />

lunar rovers. In addition to thousands of photographs,<br />

<strong>the</strong> astronauts collected 837 pounds of<br />

rocks from <strong>the</strong> lunar regolith for study, rocks that<br />

continue to yield important information, not only<br />

about our celestial companion but also about <strong>the</strong><br />

birth of our solar system. Yet it has been 37 years<br />

since our last manned mission <strong>the</strong>re. Some blame<br />

<strong>the</strong> delay on politics—<strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong> Cold War and<br />

<strong>the</strong> space race. O<strong>the</strong>rs contend it is just a matter<br />

of money. But, of course, <strong>the</strong>re’s <strong>the</strong> plain old danger<br />

inherent in space travel. As Buzz Aldrin told<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> Journal in <strong>the</strong> wake of <strong>the</strong> February<br />

2003 Columbia disaster, “<strong>The</strong> most dangerous<br />

part of our Apollo 11 Moon landing, <strong>the</strong> descent<br />

to <strong>the</strong> lunar surface, was accomplished in <strong>the</strong> face<br />

of onboard computer failures, faltering telemetry,<br />

a field of boulders, and only seconds of remaining<br />

fuel, which prompted Flight Director Gene Kranz<br />

to quip, ‘You’d better remind <strong>the</strong>m <strong>the</strong>re ain’t no<br />

damn gas stations on <strong>the</strong> Moon.’” In a recent<br />

interview with <strong>Explorers</strong> Journal columnist Jim<br />

Clash, Neil Armstrong amplified Aldrin’s remarks,<br />

saying, “Our landing was a very high-risk situation.<br />

Walking on <strong>the</strong> surface was, in my opinion at <strong>the</strong><br />

time, far less risky. But it was genuine exploration<br />

at a place where no o<strong>the</strong>r human, as far as we<br />

knew, had ever stepped before.”

DESTINATION MOON #1<br />

A n e w a g e<br />

in global space leadership<br />

As many of my fellow Americans and people <strong>the</strong><br />

world over mark <strong>the</strong> fortieth anniversary of my<br />

flight to <strong>the</strong> Moon aboard Apollo 11, we should<br />

understand <strong>the</strong> true legacy of that pioneering<br />

mission. Beyond <strong>the</strong> science, beyond <strong>the</strong><br />

engineering excellence, beyond <strong>the</strong> Cold War<br />

by Buzz Aldrin<br />

challenge, Apollo was much more. <strong>The</strong> entire<br />

space program, with special emphasis on <strong>the</strong><br />

attention given to Apollo, was a crown jewel in<br />

America’s strategic global vision. It was not only<br />

a testament to <strong>the</strong> strength of America’s capitalist<br />

economy and technical prowess, but a vision of<br />

Buzz Aldrin floats in space during <strong>the</strong> Gemini XII mission, November 12, 1966, image courtesy NASA.<br />

20

leadership that we wished <strong>the</strong> world to emulate.<br />

Cast in terms of a peaceful quest for scientific<br />

and engineering excellence, it was a powerful foreign<br />

policy tool. Nations that may have opposed<br />

U.S. foreign policies, such as our presence in<br />

Vietnam, and even our Cold War adversaries, admired<br />

America for <strong>the</strong> boldness and openness of<br />

its lunar exploration program. While NASA went<br />

to <strong>the</strong> Moon, it did so with <strong>the</strong> hopes, dreams, and<br />

<strong>the</strong> admiration of <strong>the</strong> people of Earth, who embraced<br />

<strong>the</strong> journey as an endeavor for humankind.<br />

We went to <strong>the</strong> Moon, but it was a journey shared<br />

and embraced by all. New global partnerships<br />

were formed and cultural exchanges made. It became<br />

a shining symbol of all that America aspired<br />

to be, and why we sought to be <strong>the</strong> world’s leader<br />

in science and technological progress.<br />

During <strong>the</strong> three decades since Apollo, however,<br />

America has decidedly remained in low-Earth<br />

orbit. With a space transportation system that has<br />

been hobbled by budget cuts and two avoidable<br />

Space Shuttle accidents, <strong>the</strong> nation’s resolve to<br />

fully support human space travel has been weakened.<br />

And sadly, our leadership tradition, forged<br />

during <strong>the</strong> glory days of <strong>the</strong> early space program,<br />

has given way to a focus on hardware and not on a<br />

broader vision. But it doesn’t have to be that way.<br />

If we wish to resume our leadership role in global<br />

space exploration we need to return to strategic<br />

thinking in terms of <strong>the</strong> value of space exploration.<br />

Today, <strong>the</strong> American space program’s most<br />

successful achievement—<strong>the</strong> building of <strong>the</strong><br />

International Space Station (ISS), our permanent<br />

home in Earth’s orbit—has been overshadowed by<br />

cost overruns, political turf battles, and a colonial<br />

mentality in which <strong>the</strong> U.S. dictates who gets to<br />

play and who doesn’t. In this context, <strong>the</strong> ISS has<br />

yet to realize its full potential as a truly international<br />

endeavor for space-faring nations across <strong>the</strong><br />

globe. While many international partners helped<br />

to create this incredible engineering achievement,<br />

we have not always treated <strong>the</strong>m as true<br />

partners. Access to <strong>the</strong> station is limited, and it<br />

is difficult for new partners to become players in<br />

this new high frontier. Instead of using <strong>the</strong> ISS as<br />

a symbol of America’s strategic leadership and<br />

technological capability, its use is limited to only<br />

a handful of nations.<br />

In this year of Apollo commemorations, it is<br />

time to open <strong>the</strong> space frontier to <strong>the</strong> world—for all<br />

who would choose to participate in it. As we near<br />

completion of <strong>the</strong> International Space Station, we<br />

should rededicate it to a purpose that is worthy<br />

of its name—an international global commons for<br />

<strong>the</strong> space-faring community of nations—led by, not<br />

dominated by, America.<br />

It is time that every nation that would like to play<br />

a role in <strong>the</strong> ISS be given an opportunity to do so.<br />

If we, as Americans, seek to improve our image<br />

aboard, <strong>the</strong>n we can better do so with engagement<br />

than with competition. And, we should add <strong>the</strong>se<br />

new players to <strong>the</strong> ISS as true partners, not just<br />

participants. We should see <strong>the</strong>ir quest for space<br />

in <strong>the</strong> same light as own: for national strategic values<br />

and for technological development. With <strong>the</strong><br />

support and agreement of our current partners, by<br />

welcoming nations with space ambitions such as<br />

China, India, and Brazil to <strong>the</strong> station, we enhance<br />

our own stature, not weaken it. We should take full<br />

advantage of China’s manned space program to<br />

carry American astronauts to and from low-Earth<br />

orbit. We currently purchase flights aboard <strong>the</strong><br />

Russian Soyuz and Progress spacecraft, and with<br />

our expanded partnerships we would also have<br />

opportunities to partner with China for use of its<br />

Shenzhou for this same purpose. We should also<br />

welcome India’s new fledgling manned space program<br />

to <strong>the</strong> new global commons that <strong>the</strong> space<br />

station can represent for <strong>the</strong> world.<br />

Through partnering and using <strong>the</strong> resources of<br />

many nations, we will lower <strong>the</strong> cost of access to<br />

space while forging stronger bonds that we can<br />

build upon to journey to more distant destinations<br />

in space—<strong>the</strong> Moon, Mars, and beyond. It will<br />

be a true low-Earth orbit outpost that brings <strong>the</strong><br />

strengths and accomplishments of each partner<br />

into developing research capabilities, logistics<br />

vehicles, and launch support to sustain <strong>the</strong> station<br />

well beyond current plans to end its life by<br />

2016. With global use, <strong>the</strong> station can continue<br />

to serve mankind—and Americans—for many years<br />

to come, reaping <strong>the</strong> rewards from <strong>the</strong> billions<br />

we have invested in its use. But we must start in<br />

Earth’s orbit. It is time we made <strong>the</strong> International<br />

Space Station truly international.<br />

biography<br />

A Fellow of <strong>The</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong> and recipient of its Lowell Thomas<br />

Award (1989), Buzz Aldrin served as pilot of <strong>the</strong> Gemini 12 mission in<br />

November 1966 and as lunar module pilot for Apollo 11 in July 1969.<br />

For more on Buzz, visit his website at www.buzzaldrin.com<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>

international space station<br />

<strong>The</strong> International Space Station as seen from <strong>the</strong> departing Space<br />

Shuttle Discovery during STS-119 in March 2009. In view are <strong>the</strong> four<br />

pairs of solar arrays mounted along <strong>the</strong> newly completed Integrated<br />

Truss Structure.<br />

22

He’s a Mars Man:<br />

Catching up with<br />

Apollo 11’s Mike Collins<br />

“Mars at <strong>the</strong> Moon’s edge,” July 2003. Photograph by Ron Dantowitz, clay center observatory.<br />

Astronaut Michael Collins, who orbited <strong>the</strong><br />

Moon in <strong>the</strong> Apollo 11 Lunar Module while<br />

Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin piloted<br />

down to its surface, isn’t interested in rehashing<br />

<strong>the</strong> past—only looking to <strong>the</strong> future.<br />

When asked to describe his thoughts<br />

as Armstrong stepped onto <strong>the</strong> Moon,<br />

Collins, 78, and author of <strong>the</strong> acclaimed<br />

Carrying <strong>the</strong> Fire: An Astronaut’s<br />

Journey, bristles a bit. “If I ever knew <strong>the</strong><br />

answer to that, I’ve said it so many times<br />

it’s gotten trite.” Same response when<br />

asked about <strong>the</strong> significance of <strong>the</strong> fortieth<br />

anniversary of Apollo 11’s historic<br />

lunar landing this July. “I don’t know how<br />

I feel 40 years later. Those questions I’m<br />

not good at answering.” But bring up<br />

<strong>the</strong> subject of Mars and, like Aldrin, he<br />

comes to life. “You can put me down as<br />

being a Mars fan,” says Collins. “I would<br />

like us to have Mars be our next objective,<br />

and I’m a little concerned <strong>the</strong> focus<br />

today is too much Moon and not enough<br />

Mars. I have <strong>the</strong> feeling that a base on<br />

<strong>the</strong> Moon could be—in terms of money,<br />

time, effort, and focus—a bottomless pit,”<br />

he continues, “and it’s going to postpone<br />

<strong>the</strong> exploration of Mars, a much more<br />

interesting place and <strong>the</strong> closest thing<br />

to a sister planet. If we spend too much<br />

time on <strong>the</strong> Moon we’re not going to get<br />

to Mars, not in my lifetime, nor in your<br />

lifetime.”<br />

—Jim Cl a s h<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>

DESTINATION MOON #2<br />

Moon in hd<br />

Ja p a n’s S elene mi s s i on<br />

<strong>The</strong> Selenological and Engineering Explorer<br />

(Selene) project, launched in September 2007 by<br />

Japan’s Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), is<br />

<strong>the</strong> largest lunar mission since <strong>the</strong> Apollo program.<br />

<strong>The</strong> aim of <strong>the</strong> 22-month-long mission has been to<br />

ga<strong>the</strong>r data on <strong>the</strong> Moon’s origin and evolution—its<br />

elemental and mineralogical composition, topography,<br />

surface and subsurface structure, and <strong>the</strong><br />

nature of its remnant magnetic and gravity fields.<br />

In October 2007, Kaguya, <strong>the</strong> Selene project’s<br />

main satellite, began orbiting <strong>the</strong> Moon at an altitude<br />

of 100 kilometers above <strong>the</strong> lunar surface,<br />

capturing images of it with a high-definition television<br />

camera aboard <strong>the</strong> craft while two smaller<br />

units—a relay satellite and a VRAD satellite—were<br />

put into polar orbit.<br />

This past February, Kaguya descended to an<br />

altitude of 50 kilometers, and in April began orbiting<br />

at 30 kilometers above <strong>the</strong> surface to continue<br />

<strong>the</strong> data-collection process.<br />

In addition to <strong>the</strong> HD imagery, a laser altimeter<br />

aboard Kaguya has enabled scientists to generate<br />

a global lunar topographic map with a spatial resolution<br />

of less than 0.5°, providing lunar topography<br />

at scales finer than a few hundred kilometers.<br />

Equipment installed on Kaguya has also allowed<br />

for <strong>the</strong> observation of plasma and high-energy<br />

particles.<br />

<strong>The</strong> mission ends this June with a controlled<br />

drop of Kaguya on <strong>the</strong> lunar surface. For more on<br />

<strong>the</strong> project, visit: www.kaguya.jaxa.jp.<br />

—AMHS<br />

North pole area of <strong>the</strong> moon. image courtesy JAXA/NHK.<br />

24

DESTINATION MOON #3<br />

moon dreams<br />

by Peter H. Diamandis<br />

It has been 33 years since any nation placed a robotic<br />

explorer on <strong>the</strong> lunar surface. Now, national<br />

space agencies around <strong>the</strong> globe—in China, India,<br />

Japan, Russia, Europe, and <strong>the</strong> United States—are<br />

racing back to <strong>the</strong> Moon with a bevy of planned<br />

orbiters, landers, and, eventually, human crews.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se important national space programs may<br />

lose this race to one of <strong>the</strong> many entrepreneurial<br />

teams competing for <strong>the</strong> Google Lunar X Prize.<br />

<strong>The</strong> first era of lunar exploration lasted for a<br />

decade and a half, with robots and human <strong>explorers</strong><br />

alike accomplishing <strong>the</strong> unthinkable and<br />

giving us our first glimpses of our celestial dance<br />

partner. <strong>The</strong> six Apollo missions that put our human<br />

footprints on <strong>the</strong> Moon remain to this day<br />

one of <strong>the</strong> crowning achievements of our species,<br />