Understanding Communities: From Knowledge into Practice - nirapad

Understanding Communities: From Knowledge into Practice - nirapad

Understanding Communities: From Knowledge into Practice - nirapad

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Understanding</strong> <strong>Communities</strong>:<br />

1<br />

<strong>From</strong> <strong>Knowledge</strong> <strong>into</strong> <strong>Practice</strong><br />

In order to help communities manage AHI, it is necessary to first assess and understand<br />

the knowledge, attitudes and beliefs as well as existing practices that may influence health<br />

and health risks. Human behaviours – including animal husbandry practices – have<br />

evolved over thousands of years and are deeply ingrained in their community contexts. In<br />

addition, behaviours and practices are influenced by socio-cultural and economic factors<br />

that are not always easy to recognise and are typically difficult to address. A thorough<br />

community assessment can identify existing beliefs, attitudes and behaviours while also<br />

revealing gaps in information and barriers to risk-reducing practices, thereby providing<br />

crucial direction to the design and implementation of projects concerned with<br />

community-based management of AHI. Assessments will also enable practitioners to<br />

better understand and address factors such as socio-economic incentives and disincentives<br />

that influence AHI risk reduction [for a discussion of barriers to risk reduction and<br />

behaviour change, refer to Chapter 3, page 77].<br />

Assessments and their subsequent analyses feed <strong>into</strong> the design and implementation of<br />

projects for community-based management of AHI. Regular re-assessment and analysis<br />

ensures that programme design reflects evolving community realities, builds upon<br />

programme successes, and addresses challenges and lessons identified as a result of<br />

experience. Research and assessments can therefore be conducted at different stages in the<br />

project cycle, with different objectives and through the use of different methods.<br />

Attention to the ‘bigger picture’ of the project life-cycle is important from the early stages<br />

in designing a project. For instance, it is particularly useful to identify, from the outset, the<br />

indicators that will assist project design and ongoing assessment; the collection of<br />

information based on these indicators in a baseline assessment will enable subsequent<br />

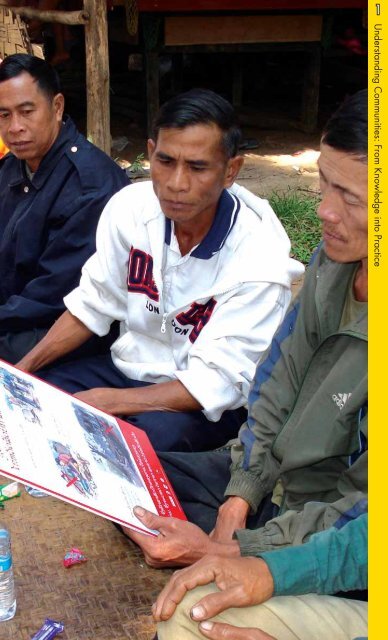

Anthropologist Benjamin Hickler undertook ethnographic<br />

research for FAO in Cambodia as part of a project that<br />

aimed to involve communities directly in the development<br />

of better focused communication strategies that would<br />

bring about the desired simple changes in their behaviour –<br />

for further information, refer to FAO Cambodia case study, page 12<br />

Photo: B. Hickler<br />

<strong>Understanding</strong> <strong>Communities</strong>: <strong>From</strong> <strong>Knowledge</strong> <strong>into</strong> <strong>Practice</strong><br />

1

The different uses of research in the project cycle<br />

based on William Novelli's 'Social Marketing Wheel'<br />

1<br />

Planning and<br />

Strategy<br />

2<br />

Selecting Channels<br />

and Materials<br />

Research<br />

3<br />

Developing<br />

Materials and<br />

Pre-testing<br />

6<br />

Feedback to<br />

Refine Program<br />

4<br />

Implementation<br />

5<br />

Assessing<br />

Effectiveness<br />

monitoring and evaluation of the effectiveness of the intervention. Therefore, while<br />

initial research and assessments at the community level might be directed to gathering<br />

information relevant to project design, this should not be done without looking at the<br />

longer-term picture and how this information might be used in later stages for assessing<br />

and improving the project and its outcomes. <br />

Research and assessments at the community level can be used at different stages in the<br />

project cycle to strengthen community-based management of AHI. Community-based<br />

research and assessments will enable practitioners to answer a number of different<br />

questions important to effective design, monitoring and evaluation of projects. For<br />

instance, questions might include:<br />

• Who is the ‘community’ – demographic composition, socio-cultural characteristics,<br />

livelihoods, etc.<br />

• What information does the community already possess about AHI and what<br />

knowledge is still missing<br />

• How do community members perceive the risks of AHI to their animals,<br />

livelihoods, health or family situation<br />

• What do people do to protect their animals and families from disease Why do<br />

they do it<br />

• How do community members obtain information How is information circulated<br />

within the community Who are the key communicators in the community<br />

Which community members are harder to reach<br />

2<br />

COMMUNITIES RESPOND<br />

Experience Sharing in Community-Based Management of Avian and Human Influenza in Asia

• What practices exist within the community that may enhance/reduce health and<br />

other risks<br />

• What barriers (cultural, societal, economic, political, etc.) exist within the<br />

community that may discourage the adoption of practices to reduce the risks of AHI<br />

• What types of incentives (economic, socio-cultural, familial, personal, etc.) may<br />

motivate community members to change their behaviour<br />

• Have risk communication messages and Information, Education and<br />

Communication (IEC) materials achieved their intended goals of increasing<br />

awareness and promoting risk reducing behaviour<br />

Research and assessments undertaken at the community level<br />

enable practitioners to target communication strategies and IEC<br />

materials to the needs and socio-cultural contexts of communities<br />

Photo: AED Lao PDR<br />

Community-level project managers have a wide variety of information collection tools at<br />

their disposal to find answers to their questions. Qualitative methods such as focus<br />

groups, key informant interviews, and ethnographic participant observation can provide<br />

understanding of why people do certain things – their beliefs, attitudes, priorities, etc.<br />

[FAO Cambodia case study, page 12]. Quantitative methods such as questionnaire-based<br />

<strong>Knowledge</strong>, Attitude and <strong>Practice</strong> (KAP) surveys can measure levels of knowledge and<br />

practices of community members, provide a representative profile of the community and<br />

monitor change over time [AED Lao PDR case study, page 7]. Such methods are<br />

particularly important in monitoring the progress of large-scale interventions and<br />

providing quantitative assessments of impacts. More qualitative methodologies – such as<br />

Participatory Learning and Action (PLA) or Participatory Action Research (PAR)<br />

approaches – can help to strengthen community participation and local ‘ownership’ of a<br />

project [for examples of PLA, refer to UNICEF Philippines and UNICEF Thailand case<br />

studies in Chapter 2, pages 59 and 66 respectively; for more information on PAR, refer to<br />

AED-UNICEF PAR Guidelines in the Resource DVD ].<br />

<strong>Understanding</strong> <strong>Communities</strong>: <strong>From</strong> <strong>Knowledge</strong> <strong>into</strong> <strong>Practice</strong><br />

3

Quick summary of methods most in use <br />

Method Key features Data generated When best to use<br />

Semi-structured<br />

interview<br />

Interview with purposefully<br />

selected key informants<br />

informally guided by<br />

pre-determined, usually<br />

open-ended questions.<br />

Can include other tools<br />

such as free-listing, top of<br />

the mind analysis, paired<br />

comparisons, etc.<br />

Qualitative:<br />

stories and quotes<br />

• Formative research<br />

at baseline<br />

• Monitoring<br />

• Evaluation<br />

Unstructured observation<br />

Wide-ranging observations<br />

of activities and<br />

behaviours gathered<br />

through participating in<br />

selected settings<br />

or at opportune<br />

moments.<br />

Qualitative:<br />

descriptions of events<br />

and processes<br />

• Formative research<br />

at baseline<br />

• Monitoring<br />

• Evaluation<br />

Focus group discussion<br />

Moderated discussion<br />

with representatives of<br />

participant groups guided<br />

by some pre-determined<br />

questions. Can include<br />

participatory tools such<br />

as seasonal calendars and<br />

vignettes.<br />

Qualitative:<br />

stories and quotes<br />

Quantitative:<br />

opinions and judgements,<br />

if using some<br />

participatory tools<br />

• Formative research at<br />

baseline<br />

• Monitoring<br />

• Evaluation<br />

Structured interview<br />

(KAP questionnaire)<br />

Interview with usually<br />

representative samples of<br />

respondents systematically<br />

guided by pre-determined,<br />

usually closed questions.<br />

Quantitative:<br />

numbers, percentages,<br />

frequencies, etc.<br />

• Formative research at<br />

baseline<br />

• Sometimes during<br />

monitoring<br />

• Evaluation<br />

Structured observation<br />

Narrowly-focused<br />

observations of activities<br />

and behaviours gathered<br />

through using a<br />

predefined checklist.<br />

Quantitative:<br />

numbers, percentages,<br />

frequencies, etc.<br />

• Formative research at<br />

baseline<br />

• Sometimes during<br />

monitoring<br />

• Evaluation<br />

There are a number of different issues to remember when selecting and refining<br />

methodologies for use at the community level. The following represents some of these key<br />

points, which are highlighted through the case studies in this chapter:<br />

• Choose a methodology which is appropriate to the community context,<br />

project-type, project cycle phase, resources and time available.<br />

• Consider the impact of research or assessments on the community and ways in<br />

which research might strengthen the involvement of the community in more<br />

participatory project design and implementation.<br />

• In order to document accurately changes/evolution in knowledge, attitudes and<br />

practices, some sort of quantitative study will be necessary. However, conduct<br />

qualitative research first to help focus and improve quantitative research. Different<br />

methodologies can complement each other and lead to more accurate results.<br />

4<br />

COMMUNITIES RESPOND<br />

Experience Sharing in Community-Based Management of Avian and Human Influenza in Asia

• Start with pre-existing, pre-tested questionnaires for quantitative research; adapt<br />

to the local context as needed.<br />

• It is never necessary to work alone or to ‘reinvent the wheel’ – collaboration with<br />

others working in the same area, use of secondary data and requests for assistance<br />

from national and regional experts will greatly facilitate community-level<br />

assessments and research.<br />

IEC materials were developed to<br />

respond to gaps in knowledge and<br />

address risky behaviours identified<br />

through KAP studies in Lao PDR;<br />

these were then pre-tested by<br />

AED in the target communities –<br />

for further information, refer to AED<br />

Lao PDR case study, page 7<br />

Photo: AED Lao PDR<br />

One commonly used<br />

quantitative tool is the<br />

KAP survey. In addition<br />

to measuring knowledge,<br />

attitudes and practices of<br />

the community, KAP<br />

studies help establish a<br />

baseline to monitor and<br />

evaluate the impact of<br />

projects and are used to<br />

measure programme<br />

success against specified<br />

indicators. KAP studies<br />

can also help project managers and community-based practitioners prioritise messages,<br />

decide what types of information are needed, which messages will be best absorbed, and<br />

how to go about communicating those messages [AED Lao PDR case study, page 7].<br />

As suggested by the table above, however, KAP studies are but one type of tool for<br />

research and assessment in communities and are not for every situation. With any tool, it<br />

is important to bear in mind its strengths and weaknesses. KAP studies typically require<br />

a large commitment in terms of expertise and resources and so are best used in large-scale<br />

or national programmes. More participatory methods may be more appropriate at the<br />

community level. Before embarking on a large-scale survey, it is important to remember<br />

that community-level organisations often have extensive skills in conducting research at<br />

the community level, and some of the participatory methodologies with which they are<br />

already familiar might present more user-friendly options that have a greater potential to<br />

strengthen partnerships with the community [for examples of participatory methodologies,<br />

refer to FAO Cambodia case study in this chapter, page 12 + UNICEF case studies in Chapter<br />

2, starting on page 55; for more information on PAR, refer to AED-UNICEF PAR<br />

Guidelines ].<br />

<strong>Understanding</strong> <strong>Communities</strong>: <strong>From</strong> <strong>Knowledge</strong> <strong>into</strong> <strong>Practice</strong><br />

5

One important lesson identified from past experience in community-level assessments<br />

and research is that community perception influences everything. Discrepancies between<br />

levels of awareness and actual changes in behaviour often relate to the degree to which<br />

people perceive their own risk, rather than awareness of risks in a more abstract sense<br />

[FAO Cambodia case study, page 12]. Studies undertaken at different stages (typically<br />

baseline versus end-line assessments such as KAP studies) can reveal changes in perceptions<br />

of risk and measure the impact of activities targeting risk behaviour. More generally,<br />

integrating research and assessments <strong>into</strong> the different stages of strategies for communitybased<br />

management of AHI enables better planned, implemented and evaluated projects<br />

and programmes that take <strong>into</strong> account community perceptions, needs and priorities.<br />

Past experience has repeatedly shown that community-level work – including research<br />

and assessments at the community level – is dependent on the trust that community<br />

members have in the practitioner or researcher. The cultivation of community trust is one<br />

of the most important factors in community-based risk management. It should not<br />

always be assumed that community members will automatically provide true answers to<br />

the questions being asked. Culturally-sensitive and expertly conducted ethnographic<br />

research or structured observation of actual behaviour might reveal gaps between what<br />

people say they do, what they actually do, and what is considered normative<br />

behaviour [FAO Cambodia case study, page 12]. The issue of trust, therefore, reminds us<br />

of the need to triangulate the findings of research and to use different methodologies to<br />

cross-check these findings. Finally, research – when of a more participatory nature – can<br />

itself be used to foster community trust and to reinforce the collaborative relationships<br />

through which community-based management of AHI might be strengthened.<br />

References:<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

USAID 2008 A Guide for Monitoring and Evaluating Avian Influenza Programs in Southeast<br />

Asia (included in the Resource DVD)<br />

AED and UNICEF 2007 Participatory Action Research on Avian Flu Communication:<br />

Summary Report and Recommendations (included in the Resource DVD)<br />

UNICEF 2006 Essentials for Excellence: Researching, Monitoring and Evaluating Strategic<br />

Communication in the Prevention and Control of Avian Influenza/Pandemic Influenza<br />

(included in the Resource DVD)<br />

Other useful materials are included in the Resource DVD – for example:<br />

DVD – Are we listening Community perceptions and Avian Influenza, B. Hickler and FAO<br />

Cambodia<br />

Bagnol, B. 2007 Participatory tools for assessment and monitoring of poultry-raising activities and<br />

animal disease control<br />

Debus M. (AED) 1990 Methodological Review: A Handbook for Excellence in Focus Group Research<br />

6<br />

COMMUNITIES RESPOND<br />

Experience Sharing in Community-Based Management of Avian and Human Influenza in Asia

AED Lao PDR<br />

A ‘consumer-oriented’ approach to research among<br />

backyard farmers in Lao PDR<br />

In Lao PDR, approximately 80 percent of poultry are kept in backyard farms. Backyard<br />

farmers are therefore a key target for AHI interventions. In order to effectively design,<br />

monitor and evaluate interventions in this broad segment of the population, it is<br />

necessary first to understand the knowledge, attitudes and behaviours of backyard<br />

farmers and – to the extent that this is possible – to quantify these measures.<br />

The Academy for Educational Development (AED)<br />

has been implementing a USAID-funded<br />

programme in Southeast Asia designed to enhance<br />

awareness and promote behaviour change among<br />

backyard poultry farmers in order to prevent and<br />

control AHI. As part of this programme, AED has<br />

conducted a baseline and end-line KAP survey<br />

Community-level assessments<br />

and research can be undertaken<br />

at different stages in the project<br />

management cycle in order to<br />

understand the dynamics of<br />

existing behavioural patterns<br />

and measure behaviour change<br />

targeting backyard poultry producers in Lao PDR (in addition to qualitative studies) in<br />

order to understand the dynamics of existing behavioural patterns and measure behaviour<br />

change. Such an understanding enables the design of more effective communication<br />

interventions.<br />

DESCRIPTION OF COMMUNITY-BASED AHI<br />

MANAGEMENT PROJECT<br />

1. Community context<br />

Lao PDR comprises a population of approximately six million, spread across<br />

17 provinces. While the majority of the population speak Lao, the country includes a<br />

diversity of ethnic groups, many of whom do not speak or read the official language.<br />

To date, Lao PDR has experienced several outbreaks of avian influenza (AI). The most<br />

severe outbreak occurred in 2007, when two fatal human infections were confirmed. More<br />

recently, in 2008 an outbreak was confirmed in Luang Namtha, near the border with<br />

China and Myanmar.<br />

<strong>Understanding</strong> <strong>Communities</strong>: <strong>From</strong> <strong>Knowledge</strong> <strong>into</strong> <strong>Practice</strong><br />

7

AED identified four priority provinces in which to focus interventions. These four<br />

provinces were selected on the basis of high risks of AHI, large and dense poultry<br />

populations, their status as key population centres and the presence of major trade routes<br />

to and from neighbouring countries. Although representing less than a quarter of the<br />

country’s provinces, these priority areas comprise almost half the population of Lao PDR.<br />

2.The community-based AHI management project<br />

This project comprised two primary objectives: to measure baseline knowledge, attitudes<br />

and practices and to provide a tool for monitoring and evaluation of interventions over<br />

time and in different areas. The KAP study tools and methods were adapted from similar<br />

studies conducted in Vietnam and Cambodia. The importance of being able to make<br />

comparisons between countries and across time was<br />

recognised. In addition to the same tools and<br />

methods, the same research company was also<br />

employed to conduct the studies. This approach<br />

enabled the studies to be as comparable as possible,<br />

leaving little room for extraneous variables.<br />

Adapting tools and methods<br />

that have already been developed<br />

and used facilitates research at<br />

the community level and enables<br />

comparisons between research<br />

results from different contexts<br />

Participatory approaches can<br />

promote stakeholder buy-in and<br />

strengthen partnerships for<br />

community-based management of<br />

AHI – for other examples, refer to<br />

UNICEF case studies in Chapter 2,<br />

starting on page 55<br />

The baseline KAP survey was conducted in<br />

September 2006; the end-line survey was<br />

conducted in October 2007. Qualitative research<br />

was also conducted throughout and beyond this<br />

period. A participatory approach was implemented<br />

in order to develop partnerships and promote the<br />

‘buy-in’ of key stakeholders, including government<br />

ministries, mass organisations, UN agencies, international NGOs and technical agencies.<br />

3. Project outcomes and outputs<br />

The KAP research confirmed some initial hypotheses and legitimised AED’s subsequent<br />

approach to awareness-raising and behaviour change strategies:<br />

• Community networks are extremely important in delivering information.<br />

• The media is vital in conveying messages, often serving as the first source of<br />

information.<br />

• Awareness is relatively ‘easy’ to influence.<br />

• Some changes in knowledge can occur<br />

quickly.<br />

• Some behavioural patterns and trends are<br />

relatively easy to change.<br />

KAP studies and other forms of<br />

research conducted at the community<br />

level can reveal networks and dynamics<br />

in the dissemination of information<br />

8<br />

COMMUNITIES RESPOND<br />

Experience Sharing in Community-Based Management of Avian and Human Influenza in Asia

The research also pointed to gaps and key lessons to take <strong>into</strong> account in managing AHI<br />

at the community level in Lao PDR:<br />

• The importance of the village chief, as a conduit for information and driver for<br />

action, was greater than initially expected.<br />

• Village veterinary workers were initially given low credibility – in particular, in<br />

comparison with village health workers.<br />

• Villagers demonstrated relatively low levels of willingness to report unusual<br />

poultry deaths.<br />

• Changes in behaviour that can be effective in curbing animal-to-animal<br />

transmission of AI were relatively slow.<br />

• Some gaps in communication and behaviour change were identified, without their<br />

causes being readily obvious. For instance:<br />

° More ‘difficult-to-change’ behaviours were<br />

detected – that is, areas where information<br />

had been transferred to community members,<br />

certain levels of knowledge and understanding<br />

were demonstrated, but behaviours did not<br />

change, or changed very little.<br />

Community-level research can<br />

reveal gaps between awareness<br />

and practice as well as<br />

barriers to behaviour change –<br />

for example, refer to FAO<br />

Cambodia case study, page 12<br />

° The KAP study allowed AED to identify such gaps, but further research was<br />

needed in order to address them.<br />

AED’s research provided guidance to the development<br />

of IEC materials, which were later pre-tested at the<br />

community level<br />

<strong>Understanding</strong> <strong>Communities</strong>: <strong>From</strong> <strong>Knowledge</strong> <strong>into</strong> <strong>Practice</strong><br />

9

AED used the results of the KAP studies for a number of purposes:<br />

• Developed and refined mass media strategies<br />

• Developed and refined community awareness-raising and behaviour change strategies<br />

• Developed and revised communication materials, including advocacy and education<br />

materials, media materials, and training resources, with a strong emphasis given to<br />

reaching community members with low levels of literacy and on using key<br />

community figures who would act as mobilisers and educators [for discussion of the<br />

role of Lao village leaders in promoting risk reduction messages, refer to UNICEF case<br />

study in Chapter 2, page 55]<br />

• Shared survey tools and methods with partners in Lao PDR in order to promote<br />

standardisation of research, monitoring and evaluation<br />

4. Partners<br />

AED worked with a number of key players during the implementation of this project.<br />

The various ministerial bodies of the Lao government – under the guidance of the<br />

National AHI Coordination Office (NAHICO) – provided support, guidance, cooperation<br />

and technical expertise, as well as facilitating introductions and access to<br />

communities and community leaders. FAO provided technical expertise – especially in<br />

relation to issues surrounding transmission and prevention of AI – facilitated access to<br />

communities, and assisted with the pre-testing and development of materials. CARE<br />

adapted the survey tools and methods for use in other provinces, and UNICEF and<br />

others served as collaborating partners.<br />

Pre-testing of IEC posters in Oudomxay<br />

village, Lao PDR<br />

10<br />

COMMUNITIES RESPOND<br />

Experience Sharing in Community-Based Management of Avian and Human Influenza in Asia

LESSONS IDENTIFIED<br />

1. Specific lessons<br />

• Research is more effective with stakeholder buy-in.<br />

• KAP studies highlight patterns and changes in knowledge, attitudes and practices.<br />

• KAP studies point to gaps and priority areas for awareness-raising and behaviour<br />

change.<br />

• Qualitative research should be used to<br />

complement KAP studies – addressing<br />

gaps in research and contributing to the<br />

development of effective communication<br />

materials and interventions.<br />

Qualitative research can complement<br />

quantitative studies, to provide a fuller<br />

picture of factors influencing behaviour<br />

at the community level – for example,<br />

refer to FAO Cambodia case study,<br />

page 12<br />

2. Cross-cutting lessons<br />

• Building trust and partnerships with the community is vital.<br />

• <strong>Understanding</strong> the strengths and limits of the mass media is crucial.<br />

• Pictures and illustrations are important communication tools in communities<br />

characterised by low levels of literacy.<br />

• Identification and utilisation of existing social networks for information<br />

dissemination and promotion of behaviour change is essential.<br />

• <strong>Understanding</strong> the village context provides insight <strong>into</strong> legitimate community<br />

reactions to projects in community-based management of AHI.<br />

PROJECT & CONTACT DETAILS for further information on this case study<br />

Academy for Educational Development (AED)<br />

Anton Schneider, Country Coordinator<br />

Lao PDR<br />

Tel: +856 20 240 315<br />

E-mail: anton.schneider@gmail.com<br />

Photos and IEC materials courtesy of AED Lao PDR<br />

<strong>Understanding</strong> <strong>Communities</strong>: <strong>From</strong> <strong>Knowledge</strong> <strong>into</strong> <strong>Practice</strong><br />

11

FAO Cambodia<br />

‘Bridging the gap’ between awareness and practice:<br />

Participatory learning of rural beliefs and practices on AHI<br />

prevention and response in Cambodia<br />

Behaviour is influenced by more<br />

than just knowledge or awareness<br />

of the risks of AHI – for a discussion<br />

of some barriers to behaviour<br />

change, refer to Chapter 3, page 77<br />

AHI communication efforts in Cambodia have,<br />

from a certain perspective, been a resounding<br />

success. Research has pointed to high levels of<br />

nominal awareness – albeit more awareness of<br />

animal-to-human transmission than of animal-toanimal<br />

transmission – and high levels of understanding of the messages being promoted<br />

to reduce the risks of AHI. High levels of ‘awareness’, however, have not necessarily<br />

translated <strong>into</strong> behaviour change. Many people continue to handle and consume sick<br />

birds or birds that have died of unexplained diseases; the use of gloves or masks when<br />

handling poultry is uncommon; low levels of reporting persist; there still exist a multitude<br />

of erroneous beliefs about the transmission of AHI; and biosecurity is almost non-existent.<br />

This FAO-led study used mixed methods – including participatory assessment tools and<br />

ethnographic research – to highlight the beliefs and practices of smallholder poultry<br />

producers in rural Cambodia. The objective was to reveal local understandings of poultry<br />

disease in general and of AI in particular. The striking gap between high levels of<br />

awareness of key risk reduction messages and the systematic prevalence of high-risk<br />

behaviours among target audiences in rural Cambodia motivated the research, which<br />

eventually concluded with the recommendation that, to bridge the gap between awareness<br />

and behaviour change, communicators should build upon rather than ignore pre-existing<br />

understandings and practices. Messages should be delivered in ways that make sense from<br />

the point of view of the target audience.<br />

Ny Mouyry facilitated group discussions with community members and key informant interviews in order<br />

to gain a better understanding of barriers to behaviour change<br />

12<br />

COMMUNITIES RESPOND<br />

Experience Sharing in Community-Based Management of Avian and Human Influenza in Asia

DESCRIPTION OF COMMUNITY-BASED AHI<br />

MANAGEMENT PROJECT<br />

1. Community context<br />

The project was implemented in 13 districts within seven provinces – Prey Veng, Svay<br />

Rieng, Kampong Cham, Takeo, Kampot, Siem Reap and Ratanakiri. Four different types<br />

of communities comprising small-scale poultry producers were targeted:<br />

a) communities that had not experienced AHI first-hand but were located in areas<br />

characterised by high human and poultry densities, many smallholdings of<br />

household poultry, and significant cross-border poultry movements;<br />

b) communities in villages and districts with past first-hand experience of AHI (four<br />

of the villages had experienced AI outbreaks in poultry and two villages had seen<br />

human cases of AI infection);<br />

c) communities with high proportions of households relying on backyard poultry<br />

production for income; and<br />

d) communities in five villages in Ratanakiri province characterised by co-existence of<br />

backyard farmers, migrant labourers and local authorities.<br />

Samples were specifically drawn from communities comprising significant minority<br />

populations. In total, the project conducted 20 participatory discussion groups, gathering<br />

input from 190 women and 151 men.<br />

2.The community-based AHI management project<br />

This study aimed to:<br />

• explain the discrepancy between high levels of<br />

Participatory research<br />

‘awareness’ and the persistence of high-risk<br />

and anthropological studies<br />

behaviours;<br />

can reveal underlying<br />

• expose the daily realities of the target communities reasons for practices at<br />

the community level<br />

– their beliefs, values, priorities, as well as the<br />

considerations that may influence what they do and why they do it;<br />

• involve directly communities in the development of policies and practices that will<br />

affect them; and<br />

• develop a methodological platform that could be applied in different community<br />

contexts, as a way to answer similar questions concerning local beliefs and to<br />

provide explanatory models relevant to the control of zoonotic diseases such<br />

as AHI.<br />

<strong>Understanding</strong> <strong>Communities</strong>: <strong>From</strong> <strong>Knowledge</strong> <strong>into</strong> <strong>Practice</strong><br />

13

Implemented in July-August 2007, the study primarily benefited FAO staff and<br />

partners who sought to strengthen their understanding of the communities with which<br />

they work. Purposive sampling was used to target four different groups of small-scale<br />

poultry producers. Participant groups were defined and study sites were selected in<br />

consultation with FAO trainers for Village Animal Health Workers. Each trainer<br />

provided unique insight <strong>into</strong> the dynamics and<br />

characteristics of his/her respective province.<br />

These insights and understandings were then<br />

used to target specific districts, communes or<br />

villages for sampling. Permission and assistance<br />

from commune and village chiefs were sought to<br />

organise activities in a short amount of time.<br />

Working through local authority<br />

structures such as village chiefs<br />

facilitates activities at the community<br />

level and strengthens partnerships for<br />

community-based management of<br />

AHI – for another example, refer to<br />

UNICEF Lao PDR case study, page 55<br />

Short interviews with and observation of poultry<br />

buyers and vendors were conducted by the FAO research team<br />

in the target communities<br />

Research and assessment<br />

methods need to be sensitive<br />

and adapted to the sociocultural<br />

contexts in which<br />

they are used<br />

Focus group discussions (FGDs) were held in ‘natural’<br />

settings for community gatherings and generally took<br />

place outdoors in the shade of a tree, in a public space<br />

like a pagoda or schoolhouse, or in the shade of<br />

someone’s house. Initially, FGDs were divided by<br />

gender, but in several cases a small number of individuals of the opposite gender joined in<br />

and contributed to the discussions. In two cases, it was decided to conduct mixed FGDs,<br />

since previous experience had indicated that – unlike circumstances in some other<br />

cultural contexts – Khmer women were no less likely to express their opinions in the<br />

presence of men than they were in the presence of other women.<br />

14<br />

COMMUNITIES RESPOND<br />

Experience Sharing in Community-Based Management of Avian and Human Influenza in Asia

Through FGDs, the study aimed to reveal the answers to two specific questions:<br />

1. What do people already do to protect their poultry and their families from AHI<br />

2. WHY do people do what they do to protect their poultry and the well-being of their<br />

families<br />

The FAO team experienced a number of unexpected challenges when conducting FGDs.<br />

For example, the study was conducted during the rice planting season, and in two cases<br />

the village chief was unable to gather enough people together for a discussion that had<br />

been scheduled. Also, given the variety and openness of settings for FGDs, it was not<br />

uncommon for a group of spectators (usually children) to gather around and watch the<br />

proceedings. In one FGD, it appeared that participants had been provided beforehand<br />

with information about what would be discussed and how to respond to questions. This<br />

was taken <strong>into</strong> consideration during the analysis of the information that was collected<br />

through the FGD. Finally, the project timeframe did not include enough time for<br />

transcription and analysis of all the data collected through FGDs. Thus, some of the<br />

nuance and ‘richness’ that comes from verbatim transcription of participants’ responses was<br />

left out from the report.<br />

3. Project outcomes and outputs<br />

The outcomes of the study have led to the recommendation that communication<br />

strategies should build on communities’ pre-existing understandings or practices, many of<br />

which are culturally-founded. Practitioners should promote messages in a way that makes<br />

sense from the target audiences’ point of view, while ensuring that IEC materials are both<br />

practical and effective [community-level communication strategies are discussed in detail in<br />

Chapter 2, beginning on page 19].<br />

FAO has revised its training curriculum for Village Animal Health Workers taking <strong>into</strong><br />

account the results of this and other studies. A storyline was developed, with a montage<br />

of posters showing two themes: a) how the virus can be transmitted from poultry to<br />

poultry and from poultry to human; and b) prevention measures that villagers can take<br />

to prevent and control the spread of AHI. The storyline is used in forums in remote areas,<br />

where communities have limited access to radio and TV, as well as in village meetings on<br />

AHI led by local authorities in provinces bordering Vietnam, Thailand and Lao PDR. To<br />

reinforce the messages promoted by the storyline, leaflets, T-shirts and posters have been<br />

created using illustrations from the storyline. FAO also produced a video in English<br />

highlighting the findings and recommendations of the study. The film has been shown in<br />

international meetings in Bangkok and New Delhi. It has now been translated <strong>into</strong><br />

French at the request of FAO headquarters so that it can be shown at regional<br />

communication workshops in Tunisia and Senegal.<br />

<strong>Understanding</strong> <strong>Communities</strong>: <strong>From</strong> <strong>Knowledge</strong> <strong>into</strong> <strong>Practice</strong><br />

15

This study also demonstrates the importance of a multi-faceted approach to project<br />

design. The combination of tools (simple participatory tools like FGDs and key-informant<br />

interviews), metrics (for measuring understanding, practicability and different sorts of<br />

‘awareness’) and anthropological approaches assembled in this study represents a<br />

preliminary attempt to create a flexible research platform. This ‘platform’ could be applied<br />

in a variety of national or sub-national contexts in order to address a range of communication<br />

problems. But while this innovative methodological platform can be applied to other<br />

contexts, it should nevertheless be adjusted or expanded to fit a broader range of scenarios.<br />

LESSONS IDENTIFIED<br />

1. Specific lessons<br />

• The development of effective communication strategies and tools must not only<br />

be founded on sound technical recommendations but also grounded in the<br />

realities of the lives of the target audiences. Messages are more likely to succeed if<br />

they build on pre-existing understandings or practices.<br />

• Projects such as this must be flexible in their implementation strategies: along the<br />

way, there were numerous incidents that took the FAO team by surprise,<br />

requiring a shift in plans.<br />

• It is crucial to work with the local<br />

taxonomy. For example, in Cambodia<br />

dan kor kach (Newcastle Disease) is the<br />

term for a sickness in poultry<br />

characterised by seasonal surges in<br />

mortality and generally regarded as<br />

natural and harmless to humans, albeit<br />

Gaps between awareness and practice<br />

are related to the degree to which<br />

people perceive themselves to be at<br />

risk and to people’s experiences in<br />

relation to AHI – for an example of<br />

awareness-raising in an ‘AI-free zone’,<br />

refer to UNICEF Philippines case study,<br />

page 59<br />

harmful to livelihoods; it is seen as impossible to prevent and difficult to treat.<br />

Pdash sai back sey (avian influenza) is a new term that is often confused with dan<br />

kor kach, leading to similarly fatalistic attitudes.<br />

• Taking <strong>into</strong> account the local context, it is important to encourage a shift from a<br />

‘naturalist’ to a ‘contagion’ model of poultry disease and death. This modification<br />

promotes the prevention of transmission.<br />

• It is important to focus on perceptions of risk, rather than fear.<br />

• It is important to work with the communities’ attitudes that ‘hearing is just<br />

hearing; seeing is believing.’<br />

16<br />

COMMUNITIES RESPOND<br />

Experience Sharing in Community-Based Management of Avian and Human Influenza in Asia

2. Cross-cutting lessons<br />

• Messages should be connected to local values<br />

and priorities: ‘Family prosperity and well-being’<br />

was, in Cambodia, the best way to link key<br />

messages to values for which people would<br />

willingly change their behavioural patterns.<br />

• Gender should be a primary consideration in<br />

Participatory communication<br />

strategies are more effective<br />

than top-down efforts to<br />

impose ‘healthy’ behaviour –<br />

for more information, refer to<br />

Chapter 2, page 19<br />

developing and evaluating IEC materials and communication strategies.<br />

• Different approaches should be considered for households that rely on poultry as<br />

assets and for households that rely on poultry for income.<br />

• Persuading people to change how they normally go about things is difficult,<br />

especially when the intervention concerns core livelihood issues or when it<br />

contravenes long-standing ‘common sense’ that has been passed down from<br />

generation to generation. Evidence and experience have proved that communication<br />

strategies generated in collaboration with the target audiences will be more<br />

effective than those imposed without consultation or meaningful dialogue.<br />

A documentary of FAO’s work in Cambodia is included in the Resource DVD:<br />

Are we listening Community perceptions on avian influenza – B. Hickler and FAO<br />

PROJECT & CONTACT DETAILS for further information on this case study<br />

FAO HPAI Control Programme in Cambodia<br />

Maria Cecilia Dy, Information and Communication Officer<br />

4B Street 370, Boeung Keng Kang 1<br />

Phnom Penh, Cambodia<br />

Tel: +855 23 726 281<br />

Fax: +855 23 726 250<br />

E-mail: cecilia.dy@fao.org<br />

Implementing partners: Department of Animal Health and Production, Ministry of<br />

Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries.<br />

Funding agencies: USAID, the Government of Germany and the Government of Japan<br />

Photos courtesy of B. Hickler and FAO Cambodia<br />

<strong>Understanding</strong> <strong>Communities</strong>: <strong>From</strong> <strong>Knowledge</strong> <strong>into</strong> <strong>Practice</strong><br />

17