Frank Bowling: Recent Paintings - Abstract Critical

Frank Bowling: Recent Paintings - Abstract Critical Frank Bowling: Recent Paintings - Abstract Critical

frank bowling recent paintings

- Page 2 and 3: Cover: mauveblaise 2011 acrylic and

- Page 4 and 5: matissetreeblaise 2011 acrylic on c

- Page 6 and 7: 2. I was wondering if I could shape

- Page 8 and 9: marvelously articulated in a variet

- Page 10: 8 girls in the city 1991 acrylic on

- Page 13 and 14: wadi√two 2011 acrylic on canvas 7

- Page 15 and 16: eye & ball blaise 2011 acrylic on c

- Page 17 and 18: tracey’sbouquet ( At Swim Two Bir

- Page 19 and 20: SELECTED PUBLIC AND CORPORATE COLLE

frank bowling<br />

recent paintings

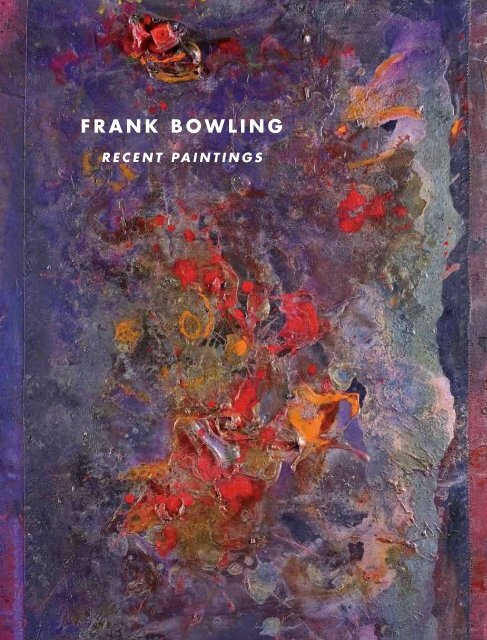

Cover: mauveblaise 2011 acrylic and mixed media on canvas 42 x 30 in.<br />

Back cover: frank bowling in his london studio, 2012<br />

Photograph by frederik bowling<br />

Published in the United States of America in 2012 by<br />

Spanierman Modern, 53 East 58th Street, New York, NY 10022<br />

Copyright © 2012 Spanierman Modern<br />

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,<br />

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by<br />

any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or<br />

otherwise, without prior permission of the publishers.<br />

isbn 978-1-935617-14-3<br />

Photography: Roz Akin<br />

Design: Amy Pyle, Light Blue Studio<br />

Lithography: Meridian Printing

frank bowling<br />

recent paintings<br />

cavedwellers 2011 acrylic on canvas 39 1 ⁄ 8 x 69 1 ⁄ 4 in.<br />

essay by carl e. hazlewood<br />

march 29 to april 28, 2012<br />

SPANIERMAN MODERN<br />

53 EAST 58TH STREET new york, ny 10022-1617 tel (212) 832-1400<br />

mcambpell@spanierman.com<br />

www.spaniermanmodern.com

matissetreeblaise 2011 acrylic on canvas 49 x 38 1 ⁄ 4 in.

FRANK BOWLING — FINDING SALVATION<br />

© Carl E. Hazlewood<br />

Art, in a sense, is a revolt against everything fleeting and unfinished in the world.<br />

Consequently, its only aim is to give another form to a reality<br />

that it is nevertheless forced to preserve as the source of its emotion.<br />

In this regard we are all realistic, and no one is.<br />

—Albert Camus<br />

1.<br />

<strong>Frank</strong> <strong>Bowling</strong>’s life and singular career have encouraged a host of speculations<br />

that engage not only the basics of his actual artistic accomplishment, but almost<br />

demand an inquiry into its sociocultural context and meaning. Born in British<br />

Guyana in 1936, <strong>Bowling</strong> is the product of speciWc tidal waves of history and world<br />

upheavals, all of which incorporate a residue of postcolonial and racial politics; thus<br />

the details and resolution of his Wnal reception in the arena of modernist art may<br />

seem fair and reasonable territory for such sociological exploration. <strong>Bowling</strong>, a<br />

man of vigorous intelligence, has on occasion taken up the intellectual and practical<br />

challenges of a dialectical joust with the forces that would deny modernity to<br />

him and those like him simply because of what they look like or where they happen<br />

to be born. While his critical writings in various art journals from the late<br />

1960s through the 70s address some of these issues, he has chosen to leave this<br />

generalized deconstruction of the self (racial, gendered, aZicted in one way or<br />

another) up to the cultural critics and historians. <strong>Bowling</strong> has never been interested<br />

in taking residence within that ahistorical cul-de-sac reserved for various<br />

“special cases”—the problematized, the romanticized, or any variety of “others.”<br />

For him, the actual revolution is located in the act of art making. Art has provided<br />

<strong>Bowling</strong> with a useful formal narrative for his work and life with its open possibilities<br />

for a poetical presentness beyond time, place, and polemics. It has become the<br />

site from which to claim a personal and an almost transcendental freedom. He has<br />

moved continually against the grain of expectations. Whatever else may be unstable<br />

in life, art—speciWcally modernist abstraction with its vaunted intellectual clarity,<br />

its visual speciWcity and “truthfulness”—has been his key to survival. As he said in<br />

an interview a few years ago, it’s rather simple—and personal: “I’m trying to Wnd<br />

my own salvation.”<br />

3

2.<br />

I was wondering if I could shape this passion<br />

Just as I wanted in solid Wre.<br />

I was wondering if the strange combustion of my days<br />

The tension of the world inside of me<br />

And the strength of my heart were enough.<br />

I was wondering if I could stand as tall<br />

While the tide of the sea rose and fell.<br />

If the sky would recede as I went<br />

Or the earth would emerge as I came<br />

To the door of the morning locked against the sun.<br />

I was wondering if I could make myself<br />

Nothing but Wre, pure and incorruptible.<br />

If the wound of the wind on my face<br />

Would be healed by the work of my life<br />

or the growth of the pain in my sleep<br />

Would be stopped in the strife of my days.<br />

I was wondering if the agony of the years<br />

Could be traced to the seed of an hour.<br />

If the roots that spread out in the swamp<br />

Ran too deep for the issuing Xower.<br />

rachel’sfootfalls 2011<br />

acrylic on canvas<br />

74 1 ⁄ 4 x 32 in.<br />

I was wondering if I could Wnd myself<br />

All that I am in all I could be.<br />

If all the populations of stars<br />

Would be less than the things I could utter<br />

And the challenge of space in my soul<br />

Be Wlled by the shape I become.<br />

—Martin Carter<br />

The poem, “Shape and Motion One,” by Guyana’s great poet/politician, Martin<br />

Carter, encapsulates the doubt, hope, and passion, engendered by the individual<br />

in the drive to transcend limitations, to become more than the sum of what one<br />

believes is possible, to defy all those things that would deWne and hold a person in<br />

place. How to Wnd one’s true self amid the quotidian pressures of life. It becomes a<br />

matter of personal discipline to translate those inchoate strivings into a meaningful<br />

4

life and a useful form. For an artist such as <strong>Bowling</strong>, history,<br />

of course, is always personal. We carry around our vulnerable<br />

childhoods just under the skin. The old homestead is there too,<br />

along with family, friends and lovers, old and new passions.<br />

It is something like the ghost of a memory—both good and<br />

bad—that continually shapes us and situates us in time. Painting<br />

insists on its own resolute history. Yet, both as viewer and<br />

practitioner, we cannot avoid bringing our personal baggage<br />

and varied experiences to bear upon whatever is yielding about<br />

its intellectual and practical discipline. Artists such as <strong>Bowling</strong><br />

are constantly working the constraints of acceptable practice . . .<br />

always pushing against its boundaries.<br />

The act of imagination is bound up with memory. You know they<br />

straightened the Mississippi River in places, to make room for houses<br />

and livable acreage. Occasionally the river Xoods these places. “Floods”<br />

is the word they use, but in fact it is not Xooding: it is remembering.<br />

Remembering where it used to be. All water has a perfect memory<br />

and is forever trying to get back to where it was. . . . It is emotional<br />

memory—what the nerves and the skin remember as well as how it<br />

appeared. And a rush of imagination is our “Xooding.”<br />

—Toni Morrison, “The Site of Memory”<br />

From the mighty Essequibo River of his childhood home in<br />

Guyana, to his residence near the Thames in Britain, the liquid<br />

energy of rivers has almost always been part of <strong>Bowling</strong>’s life.<br />

The window of his Brooklyn studio overlooks the East River.<br />

And water provides an apt metaphor for the Xuidity of the artist’s life as a Transatlantic<br />

denizen of the world, constantly transported between various zones of<br />

existence—from the new world to the old, traversing the past, the present, and all<br />

possible futures. This proliferation of socio-historical referents has prompted some<br />

critics to consider <strong>Bowling</strong>’s black Caribbean body as a political site of complex<br />

postcolonial desire. But he seeks for himself only a private and individual poetic<br />

identity, not an ideological one. The artist’s concerns are more personal and intimate<br />

than that. The titles of paintings, which mention various friends and family,<br />

give a clue to the scale of his interests. We understand names are not meant to<br />

be descriptive, but the combination of title and painting can be evocative in a<br />

poetic sense, as in Rachel’sfootfalls (2011). Tracey’sbouquet (At Swim Two Birds) (2011),<br />

john hoyland’sTie (Emanuel’s gift) 2011<br />

acrylic and mixed media on canvas 74 x 31 1 ⁄ 4 in.<br />

5

marvelously articulated in a variety of ways, represents <strong>Bowling</strong>’s more open-ended<br />

approach to painting now. Paint matter pools and is sparked alive by contrasting<br />

splashes, drips, and sprays of complementary hues; red into green equals what when<br />

bordered on one side with delicate painted lace Somewhat tender in its discrete<br />

tonalities, the painting memorializes <strong>Bowling</strong>’s aVection for the young British<br />

artist, Tracey Emin, who once sent him a bouquet of Xowers. And, John Hoyland’stie<br />

(Emanuel’s Gift) (2011) becomes an homage to the memory of <strong>Bowling</strong>’s close<br />

friend, the late British painter, John Hoyland. At the top middle of the vertical,<br />

roughly man-proportioned work we can see an unusual addition—a tiny photograph<br />

of Hoyland himself.<br />

The new paintings, like the marvelously deliquescent blue-green The Waters of<br />

Speech (2011), reveal a subtle new richness of eVect as well as color. And as always,<br />

they are evidence of an imagination seeking a visual high watermark within its<br />

own formal terms. Using a range of rich yet almost indescribable colors, <strong>Bowling</strong><br />

structures a seismological rush of paint-matter into vague geometries; it’s all<br />

about touch and light. It has little to do with the harsh sun-struck brilliance of<br />

what we normally consider to be “Caribbean” color. Instead of bright gold we get<br />

viscous paint worked to coppery nuances, or red/green tones struck through with<br />

spots and “sparks” of contrasting color. Wadi√one and Wadi√two (both 2011) are an<br />

intriguing pair of almost square paintings about six feet high. Wadi√one has a collaged<br />

violet canvas rectangle tipped to the right, with a rain of poured hues moving<br />

down its center. This tumbling rectangle threatens to unhinge the greenish gold<br />

color/space but is held in stasis and close to the surface by the skin of casual yet<br />

precisely tuned hues of the “background.” There is no pooling or dripping paint<br />

in this pair of paintings. Aside from the usual collaged canvas elements with edges<br />

deckled by the impression of staples, the surfaces seem mostly painted by brush,<br />

perhaps, or with a large palette knife. Pieces of canvas assembled into the ground<br />

and substance for <strong>Bowling</strong>’s paintings may sometimes bear saw-toothed evidence<br />

of being cut with pinking shears, recalling the artist’s life as a child in Guyana,<br />

watching his seamstress mother make dresses and saris for her clients. The stenciled<br />

patterns of leaves in Wadi√one refer back to his use in the late 1960s and early 70s<br />

of stencils to create the boundaries of those classic map shapes. This time the use<br />

is more delicate and restrained and works as “mark-making” as well as a subtle and<br />

signiWcant reference to nature outside the painting.<br />

This slip-sliding balancing act is repeated in Wadi√two, the companion piece<br />

of roughly similar dimensions. Here we see a more assertive use of paint. Instead<br />

of the absorbent warmth of the Wrst painting, staining into the cotton ground is<br />

left only along the top edges. And this tilted rectangle set against a more obvious<br />

geometric “background” design falls left this time, the opposite direction from its<br />

companion work. This shape manages not to become a box in space or even a<br />

6

tipped over painting against another painting. And here again <strong>Bowling</strong> conjures<br />

an informal balancing act, as the rectangle slides right into/onto the surface and<br />

hovers there, tense and poised with the promise of movement. The color is a richer<br />

“mauve” or plum hue, with a familiar rain of paint color rushing down its center.<br />

The structure of this work is fairly determined by its underlying geometry—not<br />

surprising for someone who once made visual improvisations based on Fibonacci<br />

sequences and whose graduate thesis was written on Mondrian. The background<br />

of Wadi√two is worked with gelled paint, which leaves “brush marks” as evidence<br />

of the passage of the artist’s hand as he activates the various quarters of the painting.<br />

Only the rectangle maintains its unprimed absorbency to paint and colored light.<br />

While most of the recent paintings—many of which date from 2011—are openly,<br />

ravishingly beautiful, others are honest and tough in asking for love. <strong>Bowling</strong> avoids<br />

the easy, the pretty, and the conventional. The light in many pictures is sometimes<br />

peculiar and personal. <strong>Paintings</strong> like Mauveblaise, Eye & Ball Blaise, Hansel’shaus, and<br />

MadambutterXy tend to revolve around a daring green/violet axis of secondaries<br />

grounded in reds with deep rich dark tones of hard-to-describe color combinations.<br />

The shapes of some paintings—tall and relatively narrow—often recall classic pieces<br />

from the 1970s but with much more coloristic daring and visual games to play.<br />

<strong>Bowling</strong>’s new paintings prove that his ongoing modernist enterprise has continued<br />

to develop in relation to his own aims; call it a restrained expressionism—or<br />

Color Field—it does not matter. What is evident is that <strong>Bowling</strong> has found a way<br />

to make a disciplined and consistent contribution to a particular stream of painterly<br />

abstraction, which remains vital and productive in his hands.<br />

Carl E. Hazlewood, born in Guyana, South America, is a visual artist, writer and curator living in Brooklyn, New<br />

York. He is the co-founder of Aljira, A Center for Contemporary Art in Newark, New Jersey. He is also currently<br />

associate editor for Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art (Duke University). He has written for many other<br />

periodicals, including Flash Art International, ART PAPERS Magazine, and NY Arts Magazine. Since 1984 he<br />

has organized numerous curatorial projects for Aljira such as Modern Life (co-curated with Okwui Enwezor). His<br />

project on behalf of Aljira, “Current Identities, <strong>Recent</strong> Painting in the United States,” was the U.S. prize-winning<br />

representation at the Bienal Internacional de Pintura, Cuenca, Ecuador, in 1994. As an independent curator, he has<br />

organized exhibitions for The Nathan Cummings Foundation, New York; Studio Museum in Harlem, New York;<br />

Hallwalls, New York; Artists Space, New York; P. S. 122, New York; among other venues.<br />

NOTES AND REFERENCES<br />

Albert Camus is quoted from Thomas B. Hanna, The Thought and Art of Albert Camus (Chicago: Henry Regnery<br />

Company, 1958).<br />

<strong>Frank</strong> <strong>Bowling</strong> is quoted from a video interview for the U.K. Government Art Collection podcast series:<br />

“Artist <strong>Frank</strong> <strong>Bowling</strong> R.A. discusses the influences on his painting in the Collection, including the landscape<br />

of Guyana and 1960s <strong>Abstract</strong> Expressionism.”<br />

The poem, “Shape and Motion One” is from Martin Carter, Poems of Succession (London: New Beacon<br />

Books, 1977).<br />

Toni Morrison, “The Site of Memory,” is from Inventing the Truth, William Zinsser, ed. (New York: Houghton<br />

MiZin Company, 1995).<br />

7

8<br />

girls in the city 1991 acrylic on canvas ( seven panels) 77 x 147 1 ⁄ 2 in.

10<br />

wadi√one 2011 acrylic on canvas 74 1 ⁄ 4 x 71 1 ⁄ 2 in.

wadi√two 2011 acrylic on canvas 71 1 ⁄ 4 x 74 1 ⁄ 4 in.<br />

11

12<br />

julie mcgee’s flowers 2011 acrylic and Mixed media on canvas 48 1 ⁄ 4 x 31 in.

eye & ball blaise 2011 acrylic on canvas 36 x 46 in.<br />

13

14<br />

midwinter bramble ( You Are My Sunshine) 2011 acrylic on canvas 39 1 ⁄ 4 x 29 5 ⁄ 8 in.

tracey’sbouquet ( At Swim Two Birds) 2011 acrylic on canvas 52 1 ⁄ 4 x 40 1 ⁄ 8 in.<br />

15

<strong>Frank</strong> <strong>Bowling</strong>, whose vibrant, color-<br />

Wlled abstract canvases earned him a place<br />

as the Wrst black Royal Academician, was<br />

born in British Guyana, South America, in<br />

1936, and moved to England in 1950. He<br />

graduated from the Royal College of Art in<br />

1962, alongside David Hockney, Ron Kitij,<br />

and Allen Jones, having been awarded a<br />

Silver Medal in Painting and a scholarship<br />

that allowed him to travel to South America<br />

and the Caribbean.<br />

<strong>Bowling</strong> Wrst visited New York City<br />

in 1961. DissatisWed at the time with his<br />

career in London, he established a residence<br />

in New York in 1966. He soon discovered<br />

that the raw vitality of the creative-cultural<br />

scene in New York suited his temperament<br />

and stimulated his art. Although his Wrst<br />

one-man exhibition in New York, held the<br />

year of his arrival, consisted of autobiographical<br />

Wgurative paintings typical of his early<br />

work, the new work the artist was producing<br />

by this time already gave evidence of the<br />

increasingly abstract work he would create<br />

in the years that followed. In fact, by the<br />

1970s, color became (and would remain) an<br />

integral part of <strong>Bowling</strong>’s paintings, the<br />

earthy hues he had been using becoming<br />

monochromatic color and his canvases<br />

increasingly non-Wgurative. While working<br />

within the Color Field idiom of Morris<br />

Louis, Jules Olitski, and Helen <strong>Frank</strong>enthaler,<br />

he also drew from Mark Rothko’s shifting<br />

and resonant color, the dynamism of Jackson<br />

Pollock’s surfaces, the powerful art of Francis<br />

Bacon, and older sources such as the radiant<br />

light in the paintings of J. M. W. Turner<br />

and the sensuous qualities in the art of John<br />

Constable. In 1971, the same year the<br />

Whitney Museum held a one-man exhibition<br />

for the artist, <strong>Bowling</strong> met the noted critic<br />

Clement Greenberg. Over the years to<br />

come, Greenberg encouraged <strong>Bowling</strong> in<br />

his commitment to modernism.<br />

From 1969 to 1972, <strong>Bowling</strong> worked as<br />

a contributing editor to Arts magazine,<br />

reviewing exhibitions in New York and<br />

London. He also wrote a series of essays on<br />

modernism and the contributions of black<br />

artists. His numerous honors include two<br />

Guggenheim fellowships, in 1967 and 1973.<br />

In 2008 he was awarded the order of the<br />

British Empire (O.B.E.) for his service to art.<br />

<strong>Bowling</strong> has also made signiWcant contributions<br />

to the art world in terms of change<br />

for black artists. In 1987 the Tate Gallery in<br />

London purchased <strong>Bowling</strong>’s Spread Out Ron<br />

Kitaj, which was the Wrst work by a living<br />

black British artist ever to be acquired by the<br />

museum, and in 2005 <strong>Bowling</strong> became the<br />

Wrst black Royal Academician.<br />

In 2011, the monograph, <strong>Frank</strong> <strong>Bowling</strong>,<br />

by professor, art writer, critic, and curator,<br />

Mel Gooding, was published by the Royal<br />

Academy of Arts, London. While addressing<br />

<strong>Bowling</strong>’s life, methods, and the poetic nature<br />

of his art, the book also attests to <strong>Bowling</strong>’s<br />

stature as one of the Wnest artists to emerge<br />

from the art circles of New York and London<br />

in recent decades.<br />

In 2012 <strong>Frank</strong> <strong>Bowling</strong>’s work will be<br />

featured in several important group exhibitions<br />

in London, including Migrations: Journeys<br />

into British Art, at the Tate Britain, and British<br />

Design 1948–2012, Innovation in the Modern<br />

Age, at the Victoria and Albert Museum.<br />

<strong>Bowling</strong>’s pour series will be shown in a<br />

solo display at the Tate Britain, curated by<br />

Courtney J. Martin.<br />

16

SELECTED PUBLIC AND CORPORATE COLLECTIONS<br />

American Telephone and Telegraph Corporation, New York<br />

Arts Council of Great Britain<br />

Boca Raton Museum, Florida<br />

Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon<br />

Chase Manhattan Bank, New York<br />

Chelsea & Westminster Hospital, London<br />

Crawford Municipal Art Gallery, Cork, Ireland<br />

Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, New Hampshire<br />

Guyana National Collection, Castellani House, Georgetown<br />

Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry, England<br />

Herbert F. Johnson Museum, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York<br />

John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, New York<br />

Kresge Art Center, Michigan State University, East Lansing<br />

Lloyds of London<br />

London Borough of Southwark<br />

Menil Foundation, Houston, Texas<br />

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York<br />

Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence<br />

Museum of Modern Art, New York<br />

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston<br />

National Gallery of Jamaica, Kingston, West Indies<br />

Neuberger Museum of Art, Purchase College, State University of New York<br />

New Jersey State Museum, Trenton<br />

Owens-Corning Fiberglass Corporation, Toledo, Ohio<br />

Phillips Museum of Art, <strong>Frank</strong>lin & Marshall College, Lancaster, Pennsylvania<br />

Port Authority of New York, World Trade Center<br />

Royal Academy of Arts, London<br />

Royal College of Art, London<br />

Tate Gallery, London<br />

University Museums, University of Delaware, Newark<br />

University of Liverpool<br />

Victoria and Albert Museum, London<br />

Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, England<br />

Westinghouse Corporation<br />

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

SPANIERMAN MODERN<br />

53 EAST 58TH STREET new york, ny 10022-1617